MM

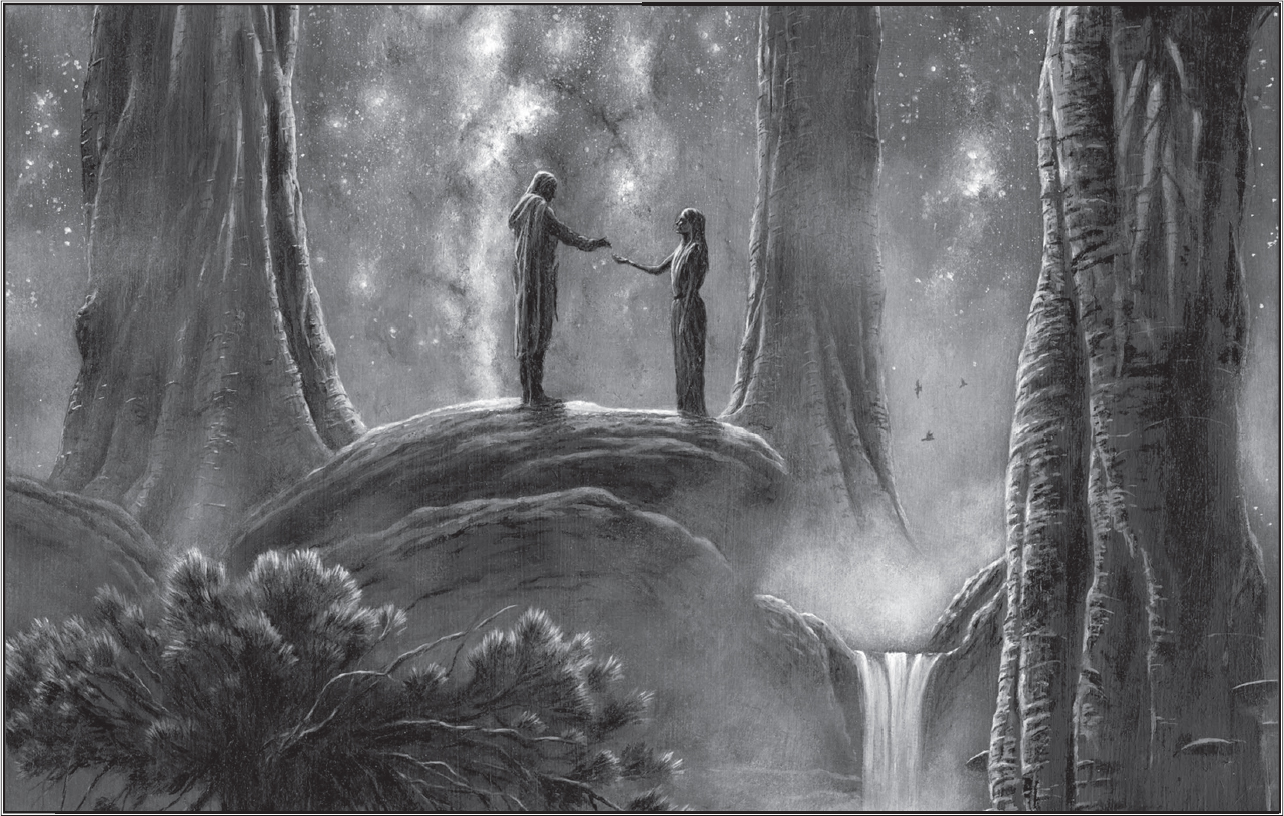

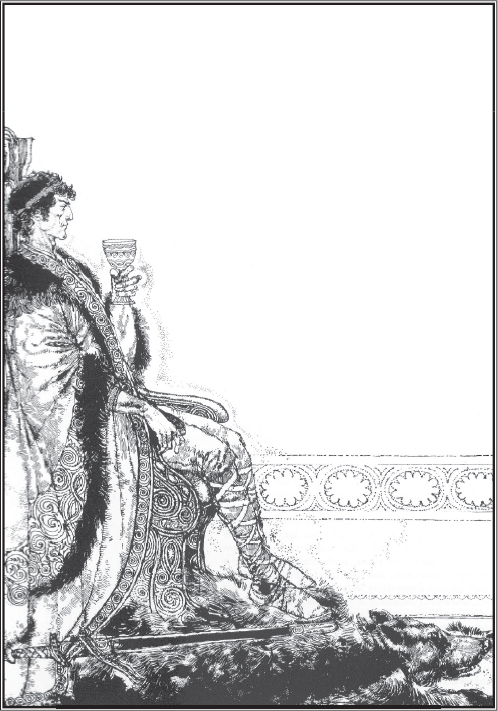

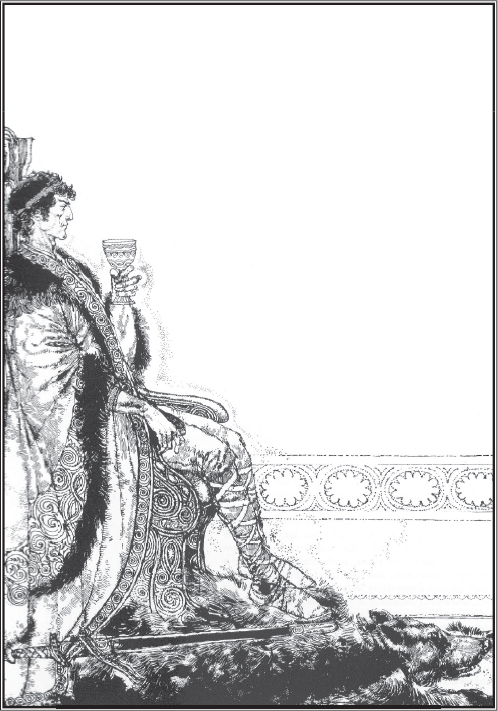

Melian, Thingol, and Lúthien

MACBETH Tragedy by William Shakespeare, probably first performed in 1606, and a play that Tolkien loved to hate. However, curiously enough it was a notable source of inspiration for The Lord of the Rings. For, although Tolkien profoundly disliked the play, he was fascinated by the historic and mythic story on which it was based. In fact, he went even further and tended to voice his dismissal of drama as a form of literature at all. In his lecture and essay “On Fairy-Stories,” Tolkien stated that, more than any other form of literature, fantasy needs a “willing suspension of disbelief” to survive. In dramatized fantasy (such as the witches scenes in Macbeth) Tolkien found “disbelief had not so much to be suspended as hanged, drawn and quartered.”

However peculiar Tolkien’s dislike of Shakespeare and Macbeth, it proved to be a very fruitful hatred. The March of the Ents was, as Tolkien explained, “due, I think, to my bitter disappointment and disgust from schooldays with the shabby use made in Shakespeare of the coming of ‘Great Birnam wood to high Dunsinane hill’: I longed to devise a setting in which the trees might really march to war.” Tolkien felt Shakespeare had trivialized and misinterpreted an authentic myth, providing a cheap, simplistic interpretation of the prophecy of this march of a wood upon a hill. And so Tolkien gives us the “true story” behind the prophecy in Macbeth in the epic March of the Ents on Isengard.

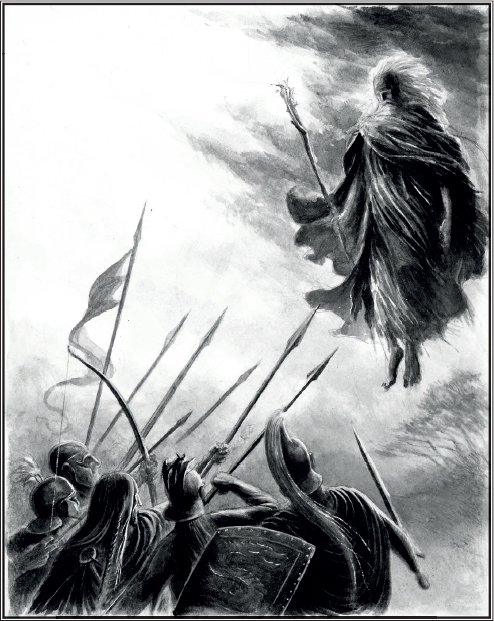

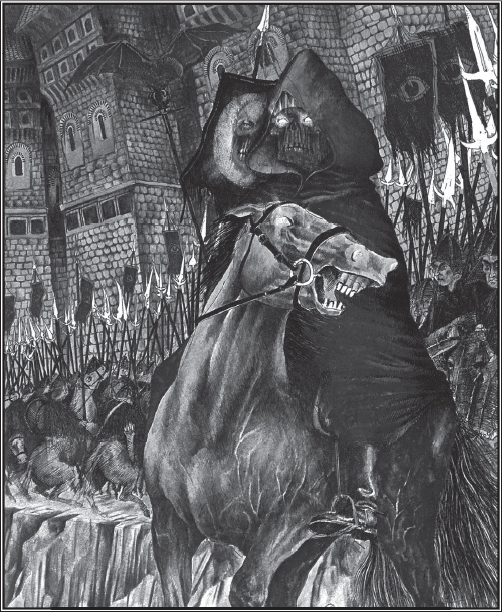

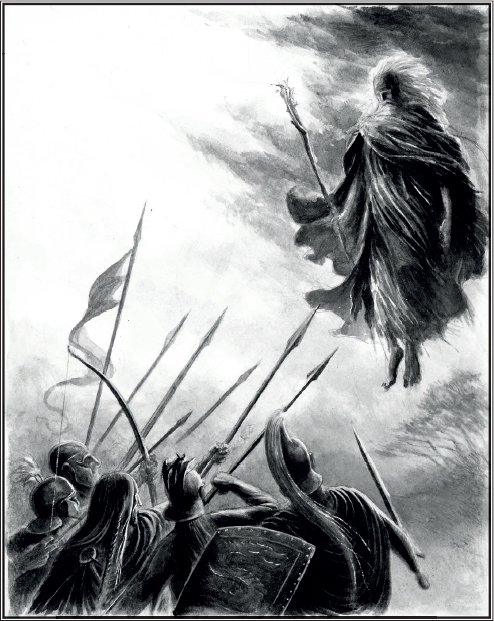

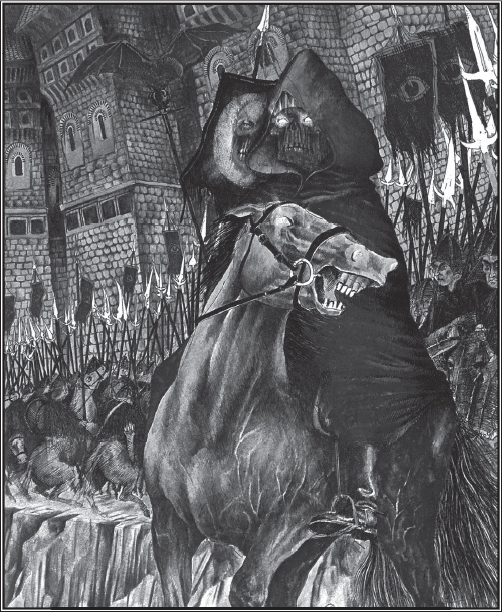

Tolkien went further still, challenging Shakespeare’s portrayal of Macbeth himself in his own evil Lord of the Ringwraiths—the Witch-king of Angmar—who sells his mortal soul to Sauron for a Ring of Power and the illusion of earthly dominion. So that none will mistake the comparison, or Tolkien’s challenge to Shakespeare, the life of the Witch-king is protected by a prophecy that is almost identical to the final one that safeguards Macbeth. In the play the witches prophesy that the murderous Scottish king should “laugh to scorn / The power of man, for none of woman born / Shall harm Macbeth.” Tolkien’s prophecy about the Witch-king—“not by the hand of man will he fall”—is certainly comparable to Macbeth’s prophecy that is circumvented when at the end of the play he is killed by Macduff, who “was from his mother’s womb / Untimely ripp’d.”

The prophecy concerning the Witch-king’s fate also proves to be simultaneously true and false. In the Battle of Pelennor Fields, the Witch-king falls “not by the hand of man” but by the hand of the shield-maiden Éowyn of Rohan and her Hobbit squire, Meriadoc Brandybuck. In this, Tolkien once again “improves” upon Shakespeare’s unsatisfactory fulfilment of the prophecy about Macbeth. And, certainly, one must acknowledge that the Witch-king’s death at the hand of a Hobbit and a woman disguised as a warrior is rather more satisfying than Shakespeare’s rather quibbling solution that someone born by caesarean section is not, strictly speaking, “of woman born.”

MAIAR (SINGULAR: MAIA) The lesser angelic powers who descend from the Timeless Halls into Tolkien’s world of Arda as servants of the more powerful Valar. The Maiar sometimes have counterparts among the gods, spirits, heroes, and nymphs of Greek and Norse mythology. The charts on pages 450 and 451 list the principal Maiar in Tolkien’s legendarium, and their possible inspirations. The resemblances are not always clear-cut. Thus Eönwë, the herald of Manwë, king of the Valar, is comparable to the Greek Hermes, the herald of the Zeus, but has little of the multifaceted, not to say mercurial, nature of Hermes who, among many other roles also guided the dead to the underworld.

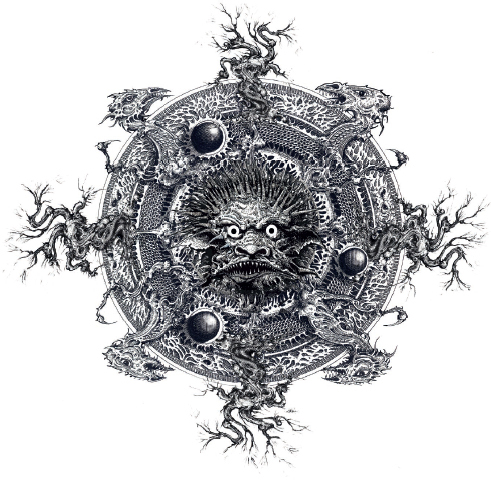

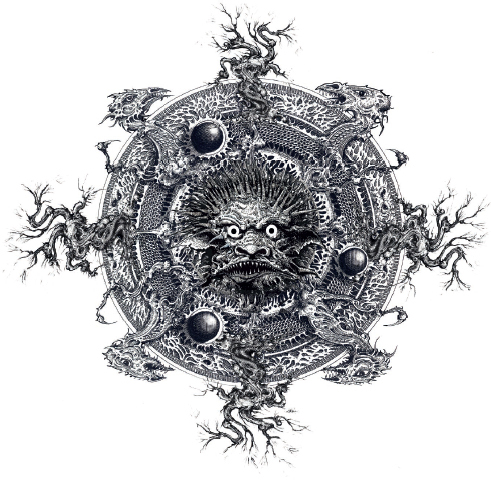

MASTER OF NON-BEING An entity in Eastern Painted Scrolls that resembles Tolkien’s Morgoth the Black Foe of the World. Few cultures have really grasped the concept of nonexistence, as have Indian and Eastern religions. Indeed, in this huge Eastern “Master of Non-Being” we have an entity comparable in form and ambition to that of the mighty Morgoth: a massive scorched black demon described as a “Black Man, as tall as a spear … the Master of Non-Existence, of instability, of murder and destruction.” And just as Morgoth the Black Foe—armed with a spear and in alliance with the great spider Ungoliant—extinguished the sacred Trees of Light in the Undying Lands, so the terrible Eastern Master “made the sun and the moon die and assigned demons to the planets and harmed the stars.”

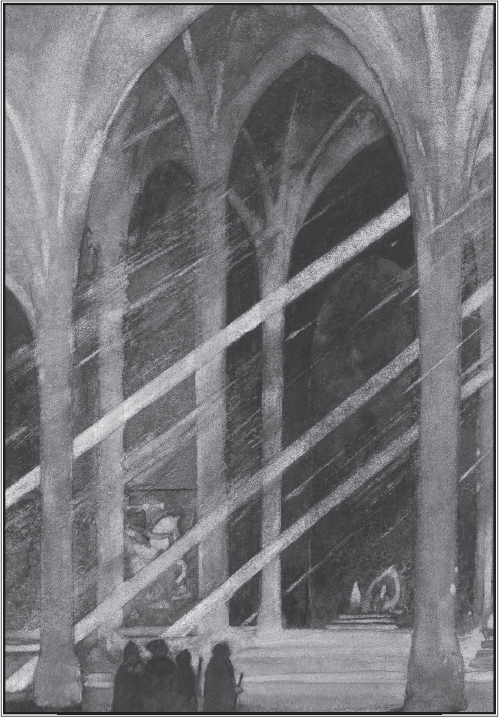

Meduseld. It is to the Golden Hall of Meduseld and King Théoden that four of the Fellowship of the Ring come, as emissaries of the Dúnedain, to call the Rohirrim to arms in the War of the Ring.

MEDUSELD The “Golden Hall” of the king of Rohan. When Gandalf rides toward the royal city of Edoras, Tolkien describes the distant sight of the gold roof of the Golden Hall of Meduseld glinting in the sunlight. The name Meduseld is Anglo-Saxon for “mead hall,” and the description of the hall is almost identical to that of Herot, the Golden Hall of King Hrothgar in Beowulf. As Beowulf approaches the kingdom of Hrothgar, the poet catches sight of Herot’s roof gables covered with hammered gold that glistens and glints in the light of the sun. Both of these great halls have even greater divine models. Meduseld has its divine model in Valinor in the Great Hall of Oromë the Horseman, and Herot’s Hall has the Great Hall of Valhalla as its divine model. This was the “Hall of Slain Heroes,” roofed with golden shields. It was the mead hall and heaven of fallen warriors, created for them in Asgard by Odin.

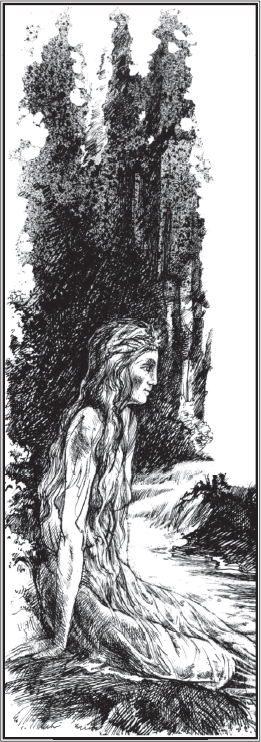

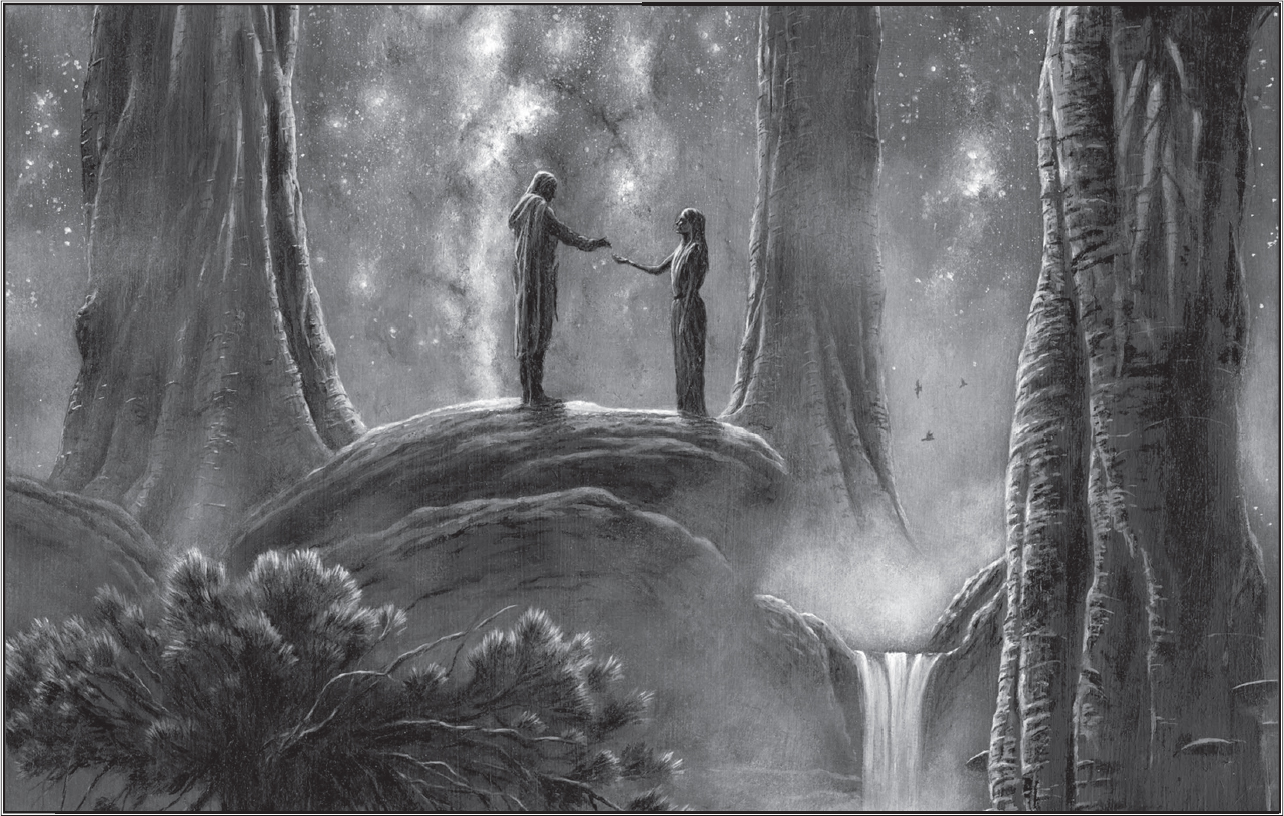

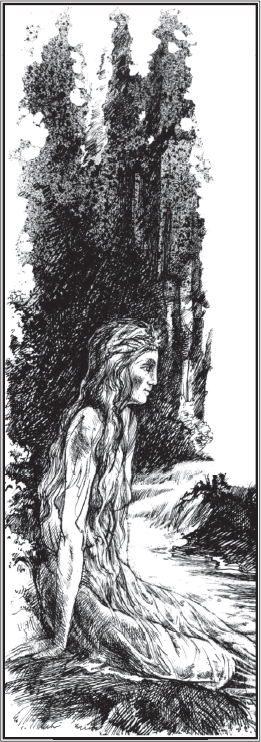

MELIAN Maia of Yavanna who early in the First Age falls in love with and becomes the wife and queen to Thingol, Sindar king of Doriath. Her love of wood and forest and the song of nightingales allies her with countless nymphs and nature spirits of mythology, while her powers as an enchantress recall the powerful female figures in Arthurian legend such as Vivien and Morgan le Fay, though without their darker aspects. Her first meeting with Thingol specifically resembles the story of how Vivien comes upon Merlin asleep beneath a thorn tree and imprisons the magician in a “tower of air” from which he can never emerge. However, while Vivien acts out of malice, Melian’s enchantment of Thingol is entirely benevolent, born out of mutual love.

MELKOR In Tolkien’s creation story Ainulindalë the most powerful, inventive, and magnificent of the angelic powers known as the Ainur but who, out of his desire to create on his account and in his own way, is corrupted and becomes Morgoth, the first Dark Lord of Middle-earth.

In Tolkien’s legendarium, he most resembles the rebel archangel Lucifer of Christian tradition, especially as depicted in John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Just as the proud Lucifer questions the ways of God, so Melkor asks why the Ainur cannot be allowed to compose their own music and bring forth life and worlds of their own. Both Tolkien’s Melkor and Milton’s Lucifer are, in one light, heroic in their steadfast “courage never to submit or yield”; however, in truth both rebel angels are primarily motivated by overweening pride and envy.

Setting himself up against the Valar, Melkor builds his fortress of Utumno in the Iron Mountains in the northern wastes of Middle-earth, and digs the foundations of his armory and dungeon of Angband. Thereafter, Melkor wages five great wars against the Valar. These wars before the rising of the first Moon and Sun and the arrival of Men within the spheres of the world are comparable to the cosmological myths of the ancient Greeks, in which the unruly Titans of the Earth rise up to fight the gods. Ultimately the titanic forces of the Earth are conquered and forced underground, just as Melkor’s forces are defeated in those primeval wars with the Valar.

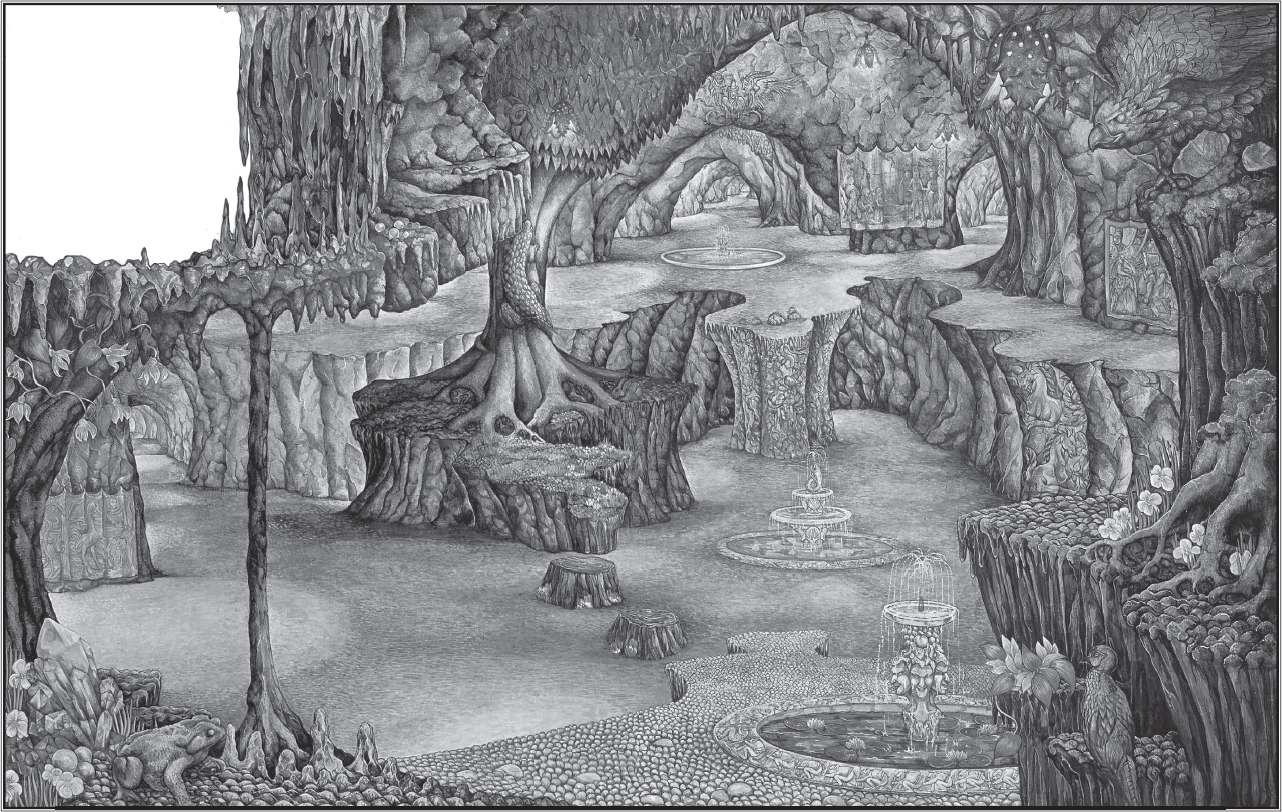

MENEGROTH

See: DORIATH; STRONGHOLDS

MERCIA Anglo-Saxon kingdom that through the sixth to ninth centuries rose to become the most powerful in Britain. This was the heartland of England Tolkien believed was for centuries the homeland of his mother’s Mercian ancestors. The name Mercia derives from “Mearc” or “Mark,” the Anglo-Saxon name for the borderland between the Celtic tribes of Wales and Anglo-Saxons of England.

This real-world history is comparable to the fictional history of Tolkien’s Middle-earth where Rohan is a borderland between the Dunlendings and Rohan’s allies in Gondor. In calling the Rohirrim cavalrymen the “Riders of the Mark,” Tolkien clearly linked his fictional Rohan to his beloved and historic Mercia. For, not only was Mercia a buffer region, but its greatest and most powerful ruler—the eighth-century King Offa—built the massive earthen wall and trench that runs over 170 miles and marks the border between England and Wales. So it seems likely that in King Offa of Mercia as the legendary builder and defender of Offa’s Dyke, Tolkien found inspiration for his fictional King Helm Hammerhand of Rohan, the legendary builder and defender of Helm’s Dike.

Melian and Thingol meet in Nan Elmoth. The story of the enchantment of Thingol by Melian recalls the enchantment of Merlin by Vivien.

In his JRR Tolkien: A Biography, Humphrey Carpenter notes that, during the time he was writing The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien took his family on a vacation outing to White Horse Hill, less than 20 miles from Oxford, on the borders of Mercia and Wessex. This is the site of the famous prehistoric image of the gigantic White Horse cut into the chalk beneath the green turf and topsoil on the hill. This White Horse undoubtedly inspired Tolkien’s image of a white horse on a green field, carried on the banners of the kings of Rohan and the Riders of the Mark.

MERCURY The Roman counterpart to the Greek god Hermes, the herald of Zeus (the Roman Jupiter) and the god of messengers, merchants, pilgrims, alchemists, and magicians. As protector of travelers, the appearance of Mercury/Hermes as a bearded wanderer in a slouch hat and traveler’s cape and carrying a staff helped provide some of Tolkien’s inspiration for his Istari Wizards, and most specifically Gandalf the Grey.

Another link of Mercury to Gandalf is the Wizard’s Elvish name Mithrandir, meaning “Grey Pilgrim” or “Grey Wanderer.” It may be supposed that when the ancients decided to assign gods and their influences to the planets, the god Mercury must have been one of their more obvious candidates. After all, the word “planet” comes from the Greek for “wanderer.” (As most stars are “fixed” in the sky, the most obvious quality of a planet is its ability to wander through the night sky, hence the use of this word for this particular meaning.) The planet Mercury is observably a silver-gray “wanderer” traveling at phenomenal speed across the night sky, visiting each god or planet, as paths cross. There could be no clearer case for matching the mercurial nature of both the planet and the god.

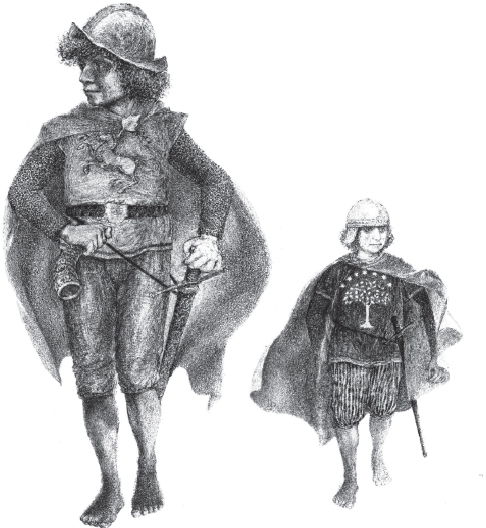

MERIADOC (“MERRY”) BRANDYBUCK

Hobbit member of the Fellowship of the Ring and heir to the Master of Buckland. For his part in the slaying of the Witch-king he became known as Meriadoc the Magnificent.

Meriadoc has a suitably prophetic name for his role as the courageous (if diminutive) squire to the king of Rohan. In origin, Meriadoc is an ancient Celtic name for the historical founder of the Celtic kingdom of Brittany, as well as the name of one of the knights in King Arthur’s court. However, as Tolkien informs us, the names Meriadoc and Merry are translations of the original Hobbitish Kalimac and Kali, meaning, “jolly.” Merry, moreover, derives from the Old English myrige, meaning “pleasant,” though, in a curious etymological twist, this appears to originate in the Prehistoric German murgjaz, meaning “short.”

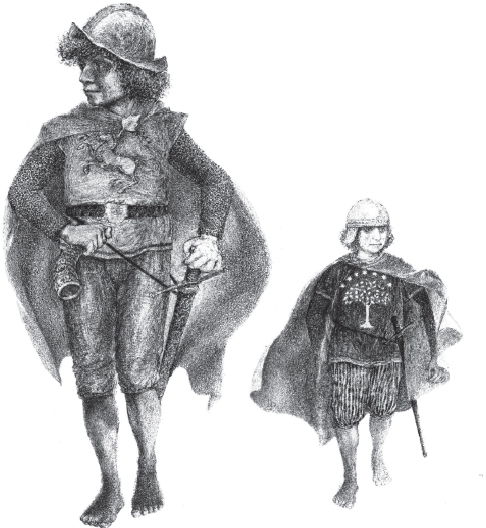

Meriadoc Brandybuck and Peregrin Took

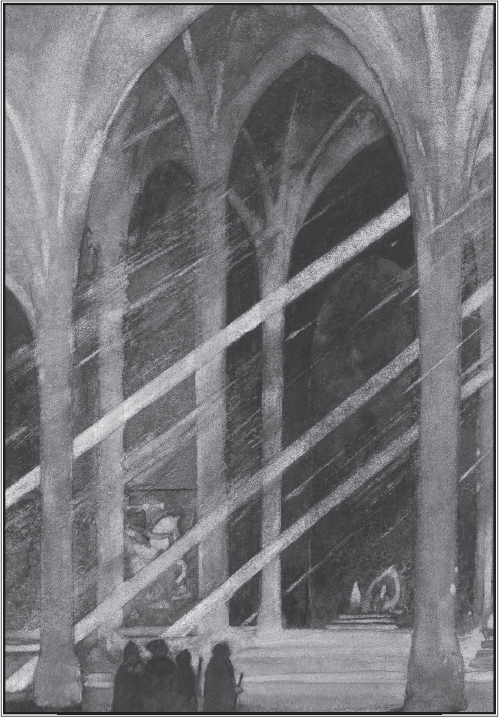

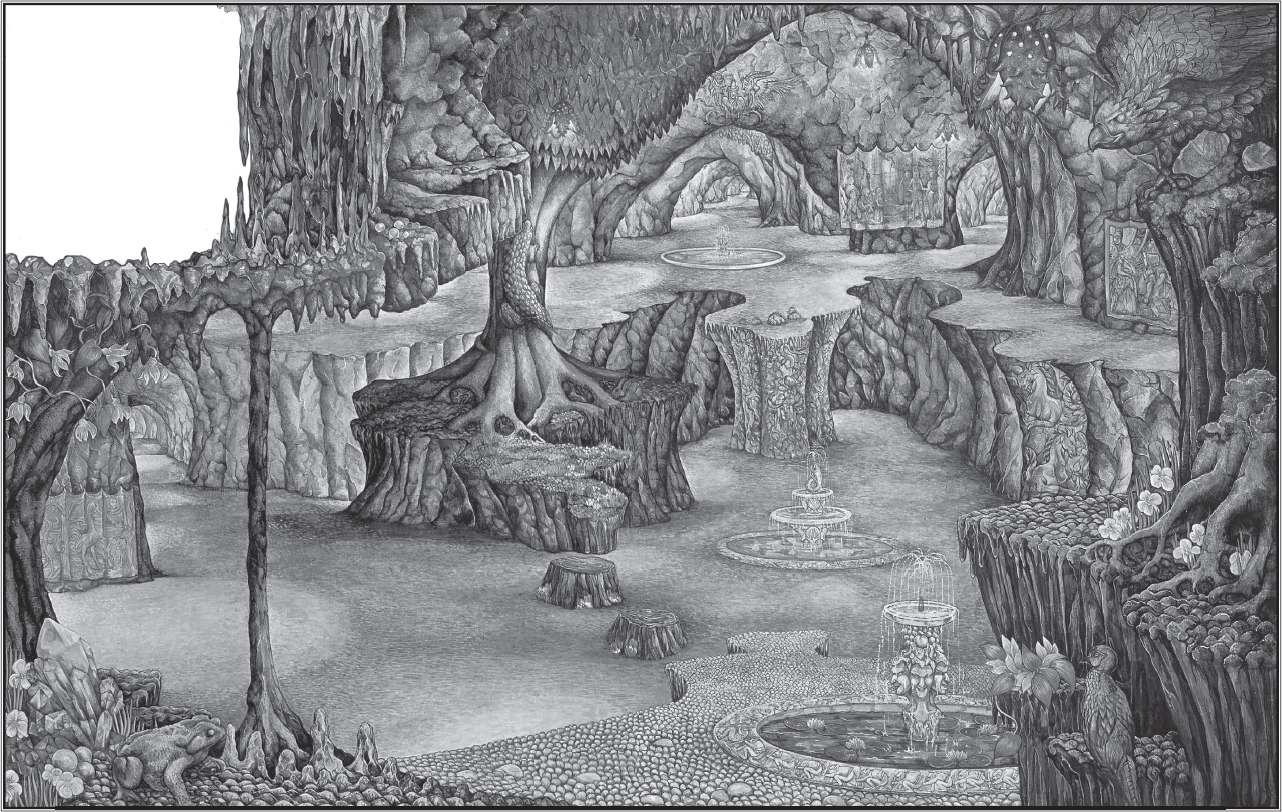

Menegroth. “The Thousand Caves,” the city fortress of the Grey-elves of Doriath in Beleriand.

Merlin. As archetypal wizard and counselor to King Arthur, Merlin is an important source for the character of Gandalf.

MERLIN In Arthurian romance the greatest of all wizards, and the mentor, adviser, and chief strategist to King Arthur. Merlin is immortal, but has mortal emotions and empathy. He is an enchanter who communes with spirits of woods, mountains, and lakes, and has tested his powers in duels with other wizards and enchantresses.

In his role as Arthur’s mentor, we can see a clear analogy with Tolkien’s Gandalf as the mentor for Aragorn II, the future king of the Reunited Kingdom of the Dúnedain. Merlin and Gandalf are both travelers of great learning, with long white beards and who carry a staff and wear broad-brimmed hats and long robes. They are both nonhuman beings. Both are counselors for future kings in peace and war, yet they have no interest in worldly power themselves.

Merlin’s imprisonment by Vivien in the forest of Brocéliande also has an echo in the enchantment of Thingol by Melian in the forest of Nan Elmoth, in Beleriand.

MICHAEL, ARCHANGEL In the New Testament Book of Revelation, the dragon-slayer in that prophetic vision of Armageddon: the great battle at the “end of time” fought between the forces of good and evil. In many of its aspects, Tolkien’s Great Battle in the War of Wrath at the end of the First Age appears to owe some of its inspiration to the biblical Armageddon. However, unlike the duel described in the book of Revelation, there is no duel between Tolkien’s Eärendil the Mariner and Ancalagon the Black Dragon. Archangel Michael and the “Red Dragon” is described in Revelation (12:7–9) as such: “Then war broke out in heaven. Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon and his angels fought back. But he was not strong enough, and they lost their place in heaven. The great dragon was hurled down—that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the whole world astray. He was hurled to the Earth, and his angels with him.” And so, just as the Red Dragon’s downfall marked Satan’s defeat, so the Black Dragon’s downfall marks the defeat of Morgoth in Middle-earth.

MIDDLE-EARTH The main continent in Tolkien’s legendarium, the northwestern regions of which provide the main setting for his epic tales. It is perhaps the most richly imagined land in fantasy fiction, meticulously detailed in terms of its geography, wildlife, peoples, cultures, and, of course, histories.

That said, Tolkien always insisted that Middle-earth is our real world—the planet Earth in another incarnation. He acknowledges in several of his letters of the 1950s that the name often confused his readers: “Many reviewers seem to assume that Middle-earth is another planet!” He found this a perplexing conclusion because in his own mind he had not the least doubt about its locality: “Middle-earth is not an imaginary world. The name is the modern form of midden-erd > middel-erd, an ancient name for the oikoumene, the abiding place of Men, the objectively real world, in use specifically opposed to imaginary worlds (as Fairyland) or unseen worlds (as Heaven or Hell).” A decade later, Tolkien famously even gave a journalist an exact geographic location: “the action of the story takes place in North-west of Middle-earth, equivalent in latitude to the coastline of Europe and the north shore of the Mediterranean …”

The confusion that arises about Middle-earth can be attributed, however, not so much to a spatial issue, but a temporal one: a question not so much of where Middle-earth is, but when. “The theatre of my tale is this earth,” Tolkien explained in one letter, “the one in which we now live, but the historical period is imaginary.”

For an explanation, one must look to the chronicles of The Silmarillion. Tolkien’s world begins with the command of Eru the One and a Great Music out of which comes forth a Vision like a globed light in the Void. This Vision becomes manifest in the creation of a flat Earth within spheres of air and light. It is a world inhabited by godlike spirits known as Valar and Maiar as well as newborn races including the Elves, Dwarves, and Ents. We are 30,000 years into this history, however, before the human race actually appears in what Tolkien calls the First Age of Middle-earth. Another 3,900 years pass before the cataclysmic destruction of the Atlantis-like civilization of Númenor during Middle-earth’s Second Age, which results in this mythical world’s transformation into the globed world we know today.

All in all, it takes some 37,000 years of chronicled history before the events described in The Lord of the Rings during the Third Age actually begin. And even after the War of the Ring in Middle-earth’s Fourth Age, we are assured that many millennia will have to pass before Tolkien’s archetypal world evolves into the real material world of recorded human history.

Tolkien himself estimated that his own time was some 6,000 years after Middle-earth’s Third Age. Working backward from our own system of time, this would place the creation of Middle-earth and the Undying Lands at 41,000 BC while the War of the Ring appears to have taken place sometime between 4,000 and 5,000 BC in our historiographical system.

This is the real trick of Tolkien’s Middle-earth: an imaginary time in the real world’s age of myth that had a parallel existence and evolution just before the beginning of the human race’s historic time. Tolkien’s Middle-earth is meant to be something akin to what the ancient Greek philosopher Plato saw as the ideal world of archetypes: the world of ideas behind all civilizations and nations of the world.

MIDGARD “Middle-earth”—one of the nine worlds in ancient Norse and Germanic mythology. It is the world inhabited by humans, as opposed to those other worlds inhabited by gods, dwarfs, elves, and other entities. Midgard was conceived as vast and flat, encircled by an ocean that is home to Jörmungandr, the Midgard Serpent, a monster that was so huge it ringed the entire world by grasping its own tail.

In his legendarium, Tolkien somewhat confusingly uses the name Arda to refer to the Earth which, as originally created, is also flat and encircled by a mighty ocean, just like the Norse Midgard. Middle-earth is only a part of Arda, a continental landmass in the middle of Arda. What he insisted upon, though, was that Middle-earth and its neighboring landmasses belonged to this Earth, “the one in which we now live,” though “the historical period is imaginary.” That is, Middle-earth exists in an archetypal age of myth, legends, and dreams that was in good part inspired by the Midgard that existed in myths, legends, and dreams of the Norsemen.

MIGRATION OF THE HOBBITS The migration of the Hobbits across Middle-Earth to their last and permanent home in the Shire. Tolkien purposely patterned the migration to match up with the migration of the historic Anglo-Saxon peoples.

The origins of both Hobbits and Anglo-Saxons are lost in the mists of time somewhere beyond a distant and massive eastern range of mountains. The ancestors of both the Hobbits and the Anglo-Saxons migrated across these mountains and eventually settled in fertile riverdelta regions. Eventually war and invaders forced the Hobbits to leave their second homeland, known as the Angle—a wedge of land between the Loudwater and Hoarwell rivers in Eriador—and migrate across the Brandywine River into what eventually became known as the Shire of Middle-earth.

Similarly, war and invaders forced the Anglo-Saxons to leave their second homeland known as die Angel—a wedge-shaped land between the Schlei River and Flensburg Fjord—and migrate across the English Channel into what eventually became known as the shires of England. Furthermore, there were three races or tribes of Hobbits, the Fallohides, Stoors, and Harfoots, which are directly comparable to the three peoples of the Anglo-Saxons (the Saxons, Angles, and Jutes).

Finally, we find the Hobbit founders of the Shire were the brothers Marcho (meaning “horse”) and Blanco (meaning “white horse”), while the Anglo-Saxon founders of England were the brothers Hengist (meaning “stallion”) and Horsa (meaning “horse”).

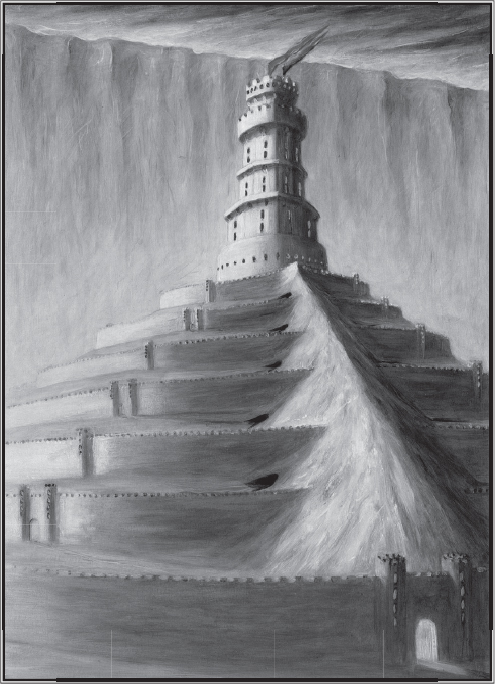

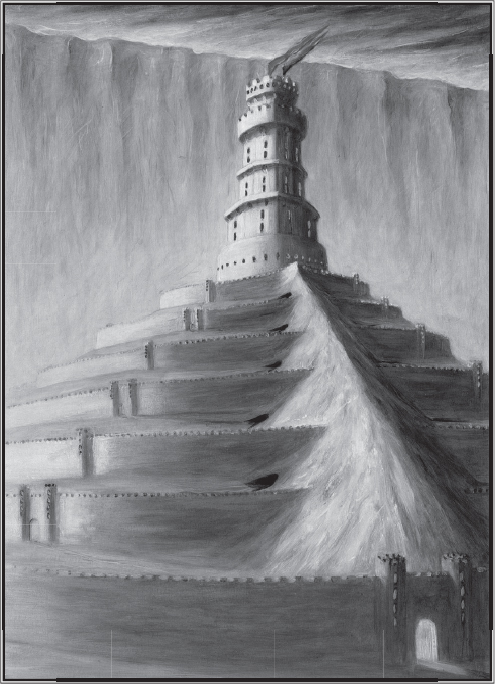

MINAS TIRITH The “Tower of the Guard” is the greatest surviving city and fortress of Gondor at the time of the War of the Ring. Originally known as Minas Anor, the “Tower of the Setting Sun,” it is a citadel built on a hill with seven levels, seven concentric walls, and seven gates, each facing a different direction. It is mostly made out of white stone, except for the lowest wall, which is made of the same impervious black stone as Orthanc.

The Migration of the Hobbits

Minas Tirith. A seven-walled citadel much like Campanella’s City of the Sun.

The Gondorian capital is comparable to the imaginary City of the Sun, a utopia devised in 1602 by the Renaissance friar and philosopher Tommaso Campanella (1568–1639): “The greater part of the city is built upon a high hill, which rises from an extensive plain, but several of its circles extend for some distance beyond the base of the hill, which is of such a size that the diameter of the city is upward of two miles, so that its circumference becomes about seven. […] It is divided into seven rings or huge circles named from the seven planets…” The City of the Sun, however, has only four principal gates, positioned at the compass points in the lowest wall—an arrangement that Tolkien considerably refined upon at Minas Tirith.

Both Minas Tirith and the City of the Sun look back to ancient mythological traditions: the ancient Sumerians believed that there were seven walls and seven gates to both heaven and hell, and the biblical paradise of Eden was surrounded by seven walls entered through seven gates. There are connections, too, with the ancient tradition of the Music of the Spheres and the divine order of the universe—a tradition that fascinated Tolkien deeply.

See also: STRONGHOLDS

MIRKWOOD A great forest in Rhovanion to the east of the Misty Mountain, home in the Third Age to Elves, Dwarves, and Men, and, for a time, Sauron, the Necromancer of Dol Guldur.

This ancient Anglo-Saxon composite word conveys the lurking superstitious dread of primeval forests. In Germanic and Norse epic poetry, the dark forest is ever present and is even sometimes specifically given the name “Mirkwood.”

In the Völsunga Saga, Sigurd the Dragon-slayer enters Mirkwood and stops to mourn the loss of the “Glittering Heath,” now ruined by the corruption of Fáfnir the dragon. The atavistic dread of the forest survives in many of the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, including “Little Red Riding Hood” and “Hansel and Gretel” and can be found, too, in Arthurian legend, where the forest represents a place of danger and dark magic but also transformation, the wild antithesis of the civilized court.

This theme of wilderness contaminated by evil is evident in Tolkien’s own spider-infested Mirkwood. But it is also in Mirkwood that Bilbo Baggins twice saves the beleaguered Company of Dwarves and really proves his mettle, becoming the true hero of his own tale.

MISTY MOUNTAINS The greatest and highest mountains in the northwest of Middle-earth, also known as the Hithaeglir, or “misty peaks,” in Sindarin. Nearly 1,000 miles long, this massive mountain range runs from the Witch-kingdom of Angmar and the Orc-hold of Gundabad in the far north to the fortress of Isengard and the Gap of Rohan in the south. The Misty Mountains were inspired by Tolkien’s walking tour of the Swiss Alps in the summer of 1911 at the age of 19 with 11 companions, including his brother Hilary and his aunt Jane Neave.

The Misty Mountains form a near-impenetrable mountain wall that separates the lands of Eriador from the Vale of Anduin in Rhovanion. There are only three possible passages through that mountain barrier: the High Pass, the Redhorn Pass, and the Dwarf tunnels of Moria. One of the peaks above Moria is called Celebril the White, or the Silvertine in the Westron common tongue. Tolkien clearly confirmed the source of its inspiration in a letter to his son Michael in which he describes the breathtaking panoramic views of the Silberhorn Mountain in the Swiss Alps as “the Silvertine of my dreams.” Furthermore, the Elvish name for the Redhorn Mountain and Pass is Caradhas (“red spike or horn”), also similarly inspired by another real-world mountain encountered on that same fateful summer walking tour. In a later note Tolkien observes: “Caradhras seems to have been a great mountain tapering upwards like the Matterhorn.”

In a notable example of life imitating art, the Misty Mountains entered into the real world or, more precisely, the real-life solar system. The International Astronomical Union, the international body of scientists responsible for naming stars and geographic features of planets and lunar bodies, voted to name all of the mountains of Saturn’s moon Titan after the mountains of Tolkien’s world. In 2012 they named a Titanian mountain range the “Misty Montes” after Tolkien’s Misty Mountains.

MORDOR The terrible mountain kingdom of Sauron the Dark Lord throughout the Second and Third Ages. Within this realm Sauron forges the One Ring in the volcanic fires of Mount Doom and gathers vast armies of Orcs, Trolls, Uruks, Southrons, and Easterlings, all in his mission to dominate and enslave the kingdoms of the Elves and Men of Middle-earth.

Tolkien likely derived the name for this evil kingdom from the Anglo-Saxon morðor, meaning “murder” or “mortal sin.” This seems an appropriate name for an evil kingdom created as an engine for slaughter. However, in Tolkien’s own invented languages Mordor means “Black Land” in the Sindarin Grey Elven tongue and “Land of Shadow” in the Quenya language of the Eldar.

Tolkien’s Mordor may have partly inspired by his experience of the heavily industrialized coal-mining and iron-smelting region of the West Midlands—just to the west of his childhood Birmingham home—known as the Black Country. This was the furnace room of the Industrial Revolution where days were made black with coal smoke and nights were made hellishly red with the flames of blast furnaces. In 2014 the Wolverhampton Art Gallery made a convincing bid for the Black Country being an inspiration for Sauron’s kingdom through an exhibition entitled “The Making of Mordor.”

Since Tolkien explained that his map of Middle-earth is essentially an overlay of the real-world map of Europe (though in an imaginary archetypal time), there have been many attempts at determining just where Mordor’s might be located in the real world. Among the suggestions are the mountainous regions of the Balkans or even Transylvania, famous as the home of Count Dracula. However, reading Tolkien’s directions, a much more likely real-world location for Mordor would be in present-day Turkey, to the south of the Black Sea.

The Destruction of Mordor

MORDRED In Arthurian legend the nephew—or even son—of King Arthur, and his opponent and slayer in the Battle of Camlann. This Arthurian villain made his first appearance in the twelfth century and soon after became synonymous with treason and evil. In Dante’s Inferno, Mordred is to be discovered in the lowest circle of Hell, the domain of traitors: “[Mordred] who, at one blow, had chest and shadow / shattered by Arthur’s hand.”

Although Tolkien employed Arthurian motifs throughout his writing, he did not care for the largely French-inspired courtly elements of medieval Arthurian romance. Consequently, his own unfinished Fall of Arthur—largely written in the early 1930s and posthumously published in 2013—is an alliterative poem of nearly a thousand stanzas in the style and meter of the Old English poem Beowulf. Its focus is Arthur as a British military leader fighting a dark shadowy army of invaders out of the east led by his nemesis, the evil knight Mordred.

In the Fall of Arthur, Tolkien describes Mordred’s dark forces: “The endless East in anger woke, / and black thunder born in dungeons / under mountains of menace moved above them.” These lines could be directly transferred to Tolkien’s Middle-earth, where they are used to describe the dark forces of Mordor. It is tempting, moreover, to link the forces of Mordor led by the Nazgûl with Tolkien’s description of Mordred’s “wan horsemen wild in windy clouds,” who appear as almost spectral warriors “shadow-helmed to war, shapes disastrous.”

In The Lord of the Rings and the War of the Last Alliance, the name of the high king of the Elves, Gil-galad (meaning “Star of Radiance”), cannot help but conjure up Galahad and the knights of the Round Table. However, most obviously, in Mordred, the Dark Knight, we have the Arthurian villain who is most akin to Sauron the Dark Lord. Consequently, it is ironic that the name Mordred, which one might assume appropriately had its origin in the homonym “More-dread,” is actually derived from the Latin meaning “moderate.” However, in terms of Tolkien’s nomenclature, Mordred would be a perfect villain’s name. Just as Morgoth in Sindarin means “Black Enemy,” Moria means “Black Chasm,” Morgul means “Black Sorcery,” and Mordor (rhyming with “murder”) means “Black Land.” So, the Middle-earth name Mordred would suggest something akin to his actual Arthurian epithet of “Black Knight.”

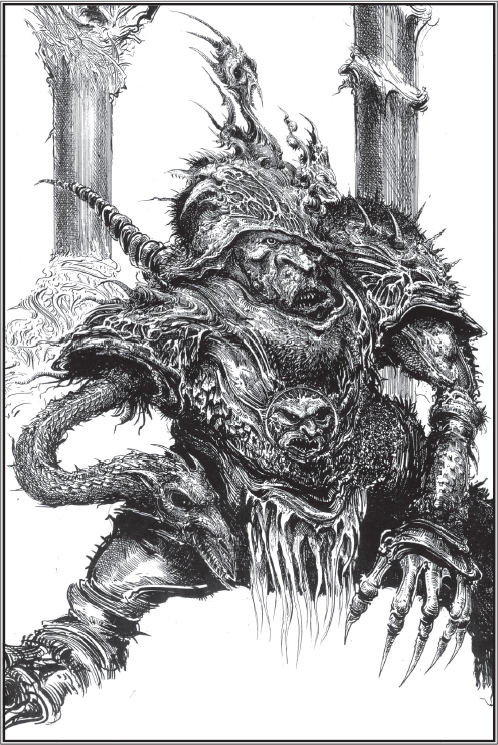

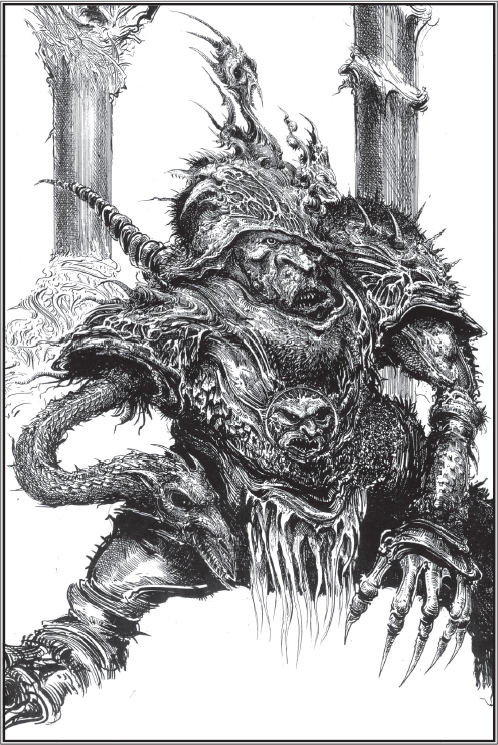

Morgoth, the Dark Enemy

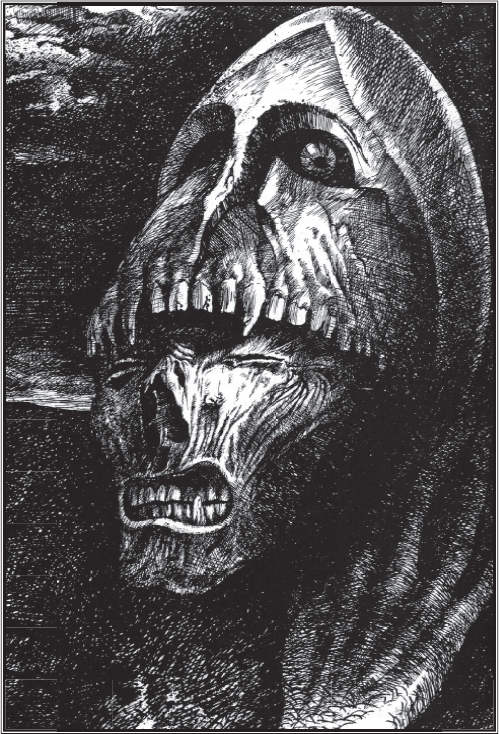

MORGOTH BAUGLIR The name given to Melkor, the greatest of the Powers of Arda, after he sinks the world into darkness with the destruction of the Trees of Light in Valinor. Morgoth means “dark enemy” and Bauglir means “tyrant or oppressor” in the Sindar Elvish tongue. In Morgoth, Tolkien tells us, “we have the power of evil visibly incarnate.” This warrior king is like a great tower, iron-crowned, with black armor and a shield black, vast, and blank. He wields the mace called Grond, the Hammer of the Underworld, which he uses to strike down his foes with the force of a thunderbolt.

Aspects of Morgoth’s dreadful nature can also be found in the tales of the ancient Goths, Germans, Anglo-Saxons, and Norsemen, where similar demonic entities may be found in conflict with pagan gods. Morgoth can be compared in Norse myth to the evil Loki who, at Ragnarök, will lead the giants in a final, world-ending battle against the gods. Loki, the trickster and transformer, was the embodiment of discord and chaos, and he also fathered the monsters that will join him at Ragnarök: Jörmungandr, the World Serpent; Hel, the goddess of the Underworld; and Fenrir the Wolf who will devour the sun and the moon.

Remarkably, other aspects of Morgoth are also comparable to the darkest aspects of Loki’s greatest foe, Odin, the king of the Norse gods. Odin is most often assumed to be comparable to Tolkien’s Manwë, the king of the Valar. However, Odin also had a terrifying amoral aspect to his worship linked to the requirement of human sacrifice. Linguistically, as well his Elvish name Mor-Goth (meaning “Dark Enemy”), this is suggestive of the dark Germanic (Gothic) “Black-Goth,” the god whom Tolkien called “Odin the Goth, the Necromancer, Glutter of Crows, God of the Hanged.”

MORIA

See: KHAZAD-DÛM

MORTE D’ARTHUR Sir Thomas Malory’s fifteenth-century account of the life of King Arthur and the exploits of his knights of the Round Table. Malory’s descriptions of Arthurian battles were authentically informed by his real-life experience as a soldier-knight in that bloody and brutal national disaster known as the Wars of the Roses (1455–87). In Malory’s account of the last Battle of Camlann, the final duel that ends with the death of King Arthur and Mordred the Dark Knight, spells an end to a utopian age of Camelot and its ideal chivalric alliance of the knights of Round Table.

Curiously, Tolkien’s description of fictional battles upon Middle-earth were authentically informed by the author’s own real-life experience as a soldier in the First World War, and specifically in the disastrous and bloody Battle of the Somme. In Tolkien’s account of the last Battle of Dagorlad, the final duel that ends with the death of Gil-galad and Sauron the Dark Lord spells an end to the age and its utopian ideal of a chivalric alliance of the “knights” of Middle-earth.

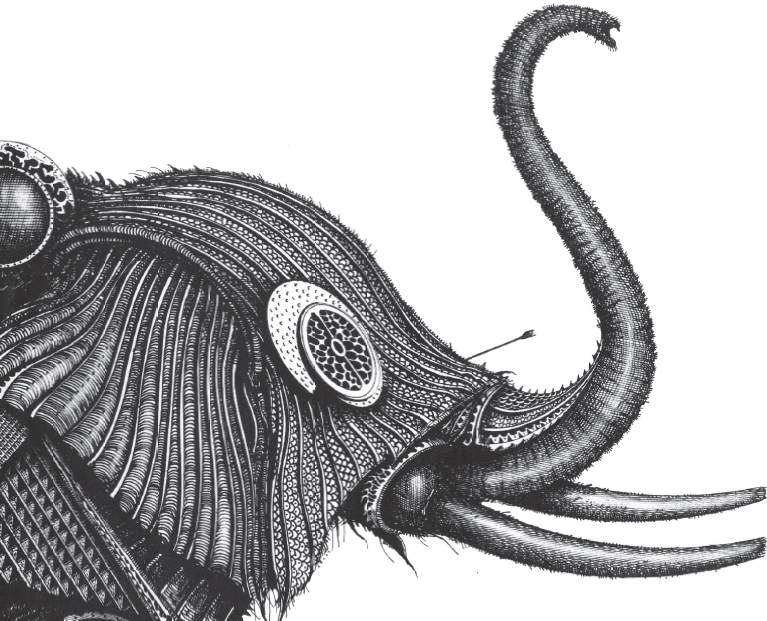

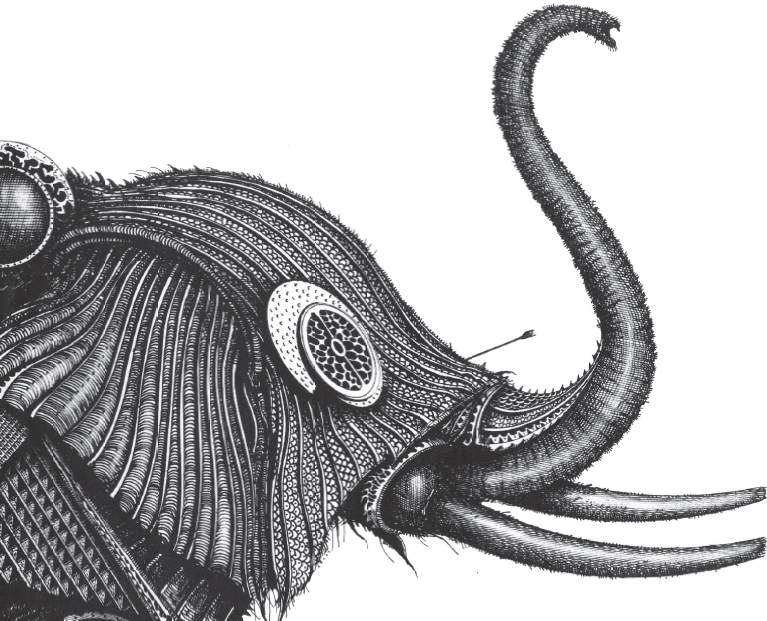

MÛMAKIL (OR MÛMAK) The massive elephant-like animals used in battle by the Haradrim, known to the Hobbits as Oliphaunts. The Mûmakil were in large part inspired by historic accounts of the use of war elephants in the Punic Wars (264–146 BC) between Rome and Carthage. The specific employment of Mûmakil by the Southrons in the Battle of Pelennor Fields may have been inspired by accounts of the historic Battle of Zama in 202 BC when the Roman army led by Scipio Africanus defeated the Carthaginian army of Hannibal with its division of war elephants.

However, Tolkien’s descriptions of the Mûmakil appear to have been rather larger and more formidable beasts than the elephants recruited by the Carthaginians. Tolkien was certainly influenced by the discovery of bones and paleolithic cave drawings of the extinct species of elephant first identified as mammoths by Georges Cuvier in 1796. Tolkien makes a clear reference to mammot—or their less hairy cousins the mastodons—in one of his annotations: “The Mûmak of Harad was indeed a beast of vast bulk, and the like of him does not walk now in Middle-earth; his kin that live still in latter days are but memories of his girth and majesty.”

“MUSIC OF THE AINUR” The Ainulindalë is Tolkien’s account of creation, imagined as a multilogue of voices in an angelic choir that evolves into a mighty operatic conflict of opposing themes of harmony and discord. The singing of the Ainur is both generative and prophetic, creating Arda as well as mapping out its destiny. It is a music filled with great beauty and sadness that foretells the fate of all that is to come into existence in the wake of the creation of the world.

Ultimately, in Tolkien’s cosmos, music is the organizing principle behind all creation. But as original as Tolkien’s “Music of the Ainur” is as a creation story, its conception is entirely consistent with another historic ancient theme known as the “Music of the Spheres.” This is perhaps the oldest and most sustained theme in European intellectual life: a belief in a metaphysical musico-mathematical system attributed to the ancient Greek mystic Pythagoras and the philosopher Plato, which was central to art and science for over 2,000 years.

The “Music of the Spheres” was a sublimely harmonious system of a cosmos guided by a Supreme Intelligence that was preordained and eternal. It is a system that (despite allowing the existence of free will) presupposes all that is, was, and will be was encoded within a celestial music. And although belief in this system has faded since the Enlightenment and the advancements of science, even during Tolkien’s lifetime—and since—this grand theme has inspired composers and artists as an expression of celestial harmony and a sense of order in the universe.

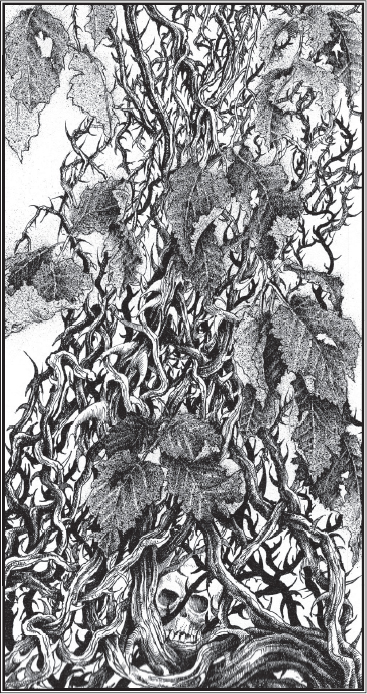

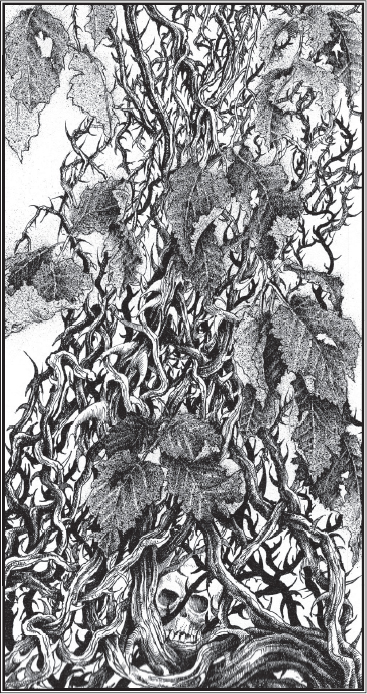

The Brambles of Mordor. The Brambles of Mordor have foot-long thorns, as barbed and dangerous as the daggers of Orcs. They sprawl over the land like the coils of barbed wire.

NN

Nidhogg

NARGOTHROND

See: MENEGROTH

NARSIL (“RED AND WHITE FLAME”) The ancestral sword of the kings of Arnor, forged by Telchar the Dwarf-smith of Nogrod in the First Age. The weapon largely owes its inspiration to the dynastic sword of the Völsungs, Gram, in the Norse Völsunga Saga.

NAUGLAMÍR A fabulous necklace created by the Dwarves of Ered Luin in the First Age and later refashioned by Thingol, king of Doriath, so that it holds the Silmaril of Lúthien and Beren. It is first mentioned in The Hobbit where the Elven-king of the Woodland Realm suggests that lust for its possession was the motive for a six-thousand-year feud between the Elves and the Dwarves. More of its tragic history emerges in The Silmarillion, where we learn that the necklace causes not only war and strife between Elves and Dwarves but also Elves and Elves, in the Second and Third Kinslayings.

In this tale, Tolkien was chiefly inspired by the Norse legend of the Brísingamen, the necklace of the Brising Dwarfs, and its theft, which resulted in endless strife and war. There may be a secondary inspiration in Greek mythology, in the cursed Necklace of Harmonia, wife of Cadmos, founder and king of Thebes. Possession of the necklace brings misfortune to all who possess it, and it is entangled in the various civil wars that plague the ancient Greek city.

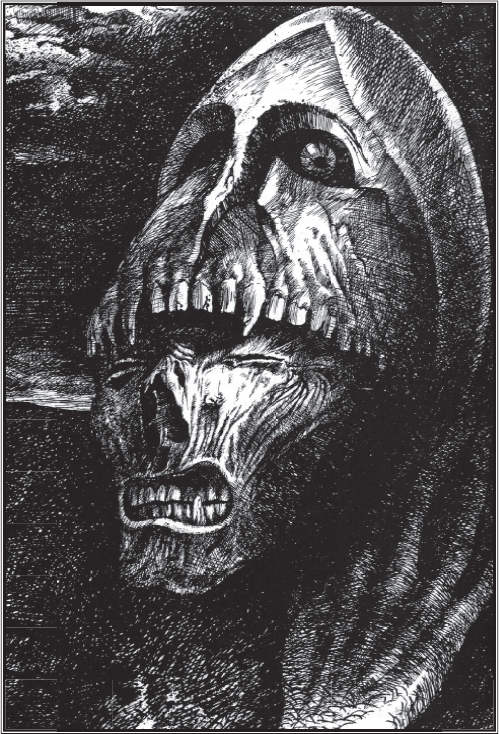

NAZGÛL The name in the Black Speech of the Orcs for the Ringwraiths, the terrible phantom nine Black Riders who are the greatest servants of Sauron the Ring Lord through much of the Second and Third

Hell-hawks. The winged steeds of their riders, the Nazgûl.

Ages. The Nazgûl were once kings and sorcerers, but Sauron corrupted them using the power of the Nine Rings of Mortal Men. In his creation of the malignant and terrifying Ringwraiths, Tolkien taps into rich lodes of mythology and legend. The wraith is a phantom or specter, either a manifestation of a living being or the ghost of a dead person. In English, “wraith” is a relatively recent word, first noted around 1513, but the notion it conveys is of vastly greater antiquity than the English language. For humans, the primal mysteries are birth and death, and of the two, death is much harder to comprehend. Fear of the dead is a powerful force in all cultures, based on the belief that if the dead were to return, it almost invariably results in evil and disaster.

The Nazgûl have immense powers over the mind and will of their foes, but they themselves are Sauron’s slaves in their every action, and they barely exist except as terrifying phantoms, acting as lethal extensions of the Ring Lord’s eternal lust for power and his desire to enslave all life. The Nine Rings of Mortal Men give the Nazgûl the power to preserve their “undead” forms as terrifying wraiths for thousands of years. Certain aspects of Tolkien’s Nazgûl are shared with the zombie, a mindless reanimated corpse set in motion by a sorcerer. However, in the Nazgûl, Tolkien created beings far more potent and malevolent. Not only are they possessed by the will of Sauron, but even before they were seduced as the Dark Lord’s thralls these were sorcerers and king of great power among the Easterlings of Rhûn, the Southrons of Harad, and the mighty Men of Númenor.

We should not overlook the fact that the Nazgûl are nine in number. It is a mystic number in both white and black magic of many nations, from the proverbial nine lives of the cat to Pythagorean numerology in which nine is assigned as the number of the tyrant. In Norse mythology, nine is by far the most significant number, from the Nine Worlds of its cosmology to the nine nights Odin the Hanged God suffered on the World Tree. The greatest Viking religious ceremonies at Uppsala lasted nine days on every ninth year. Nine is the last of the series of single numbers, and, as such, in Norse mythology and others, it is seen as symbolizing both death and rebirth. And, in Tolkien’s world, the Nine Rings are Sauron’s payment for the purchase of those nine eternally damned souls who become the nine Nazgûl.

See also: PTEROSAURS

NECROMANCY The practice of summoning the spirits of the dead as an apparition or even resurrection of the body for a variety of purposes, including divination, prophecy, obtaining forbidden knowledge, or using the deceased in an act of vengeance or terror. The word is derived from the Greek nekromanteia, meaning “divination by means of the dead body.”

Necromancers were known in ancient times among the Assyrians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. However, the Christian and Hebrew faiths both condemned the practice: The Book of Deuteronomy specifically decries necromancy as an evil act of a wizard or a witch and as “an abomination unto the Lord.”

In Tolkien’s world the mysterious Necromancer of Dol Guldur is an evil spirit that in the eleventh century of the Third Age begins to spread a terrible shadow over the southern regions of Greenwood the Great. It is something rather more than a coincidence that Tolkien’s Necromancer is eventually revealed to be Sauron the Ring Lord whose name is a Quenya word meaning “abomination.”

There is a close association between necromancy and magical rings in both the real world and Middle-earth. In the nineteenth century, the Scottish historical novelist Sir Walter Scott wrote in his Demonology and Witchcraft that he knew of many cases of necromancers who claimed to use rings to imprison and compel spirits. The sorcerous use of rings was particularly frequent in medieval Europe. In 1431, one of the many serious charges brought against Joan of Arc was the use of magic rings to enchant and command spirits.

Another case recorded by Joaliun of Cambray in 1545 related the story of a child in thrall to a crystal ring in which he “could see all that the demons within him demanded of him.” The demons of the ring so tormented him that in a fit of despair the child smashed the evil crystal ring and finally broke its spell.

Witch-king of Angmar. As his name suggests, the Witch-king of Angmar is another of the “dark lords” of Middle-earth who practices necromancy.

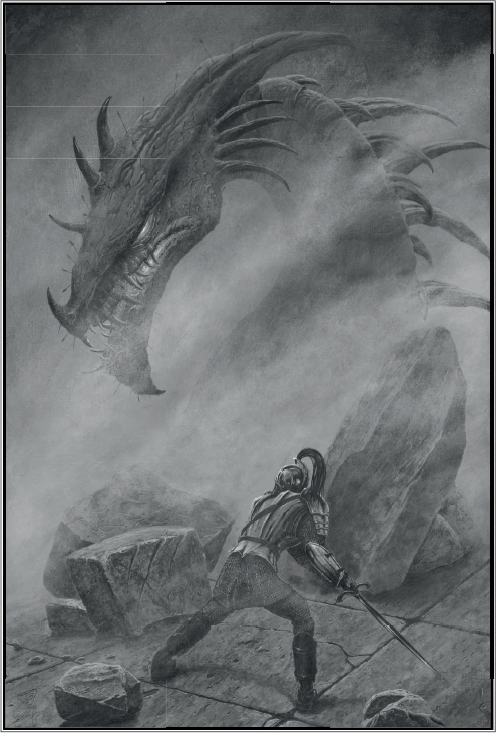

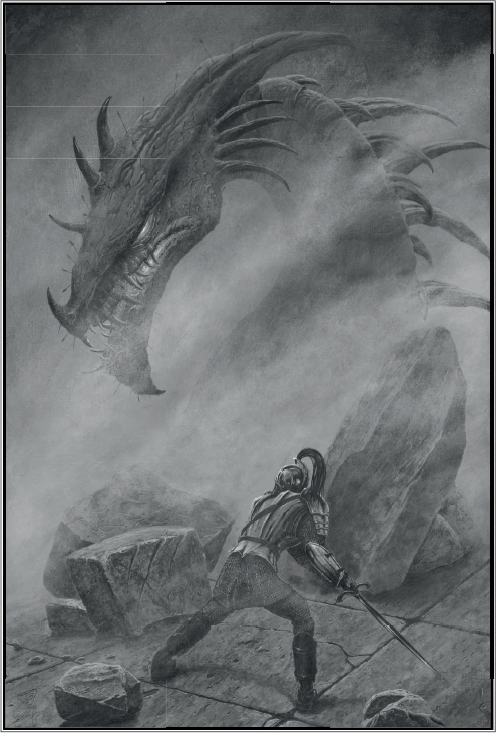

Túrin faces Glaurung on the Bridge of Nargothrond. Nargothrond is the largest kingdom of the Noldor Elves, modeled on the Thousand Caves of Menegroth. The vast complexes of this fortress–palace are expanded by the Noldor and the Dwarves of the Blue Mountains.

NEPTUNE The Roman god of the sea. For his connections with Tolkien’s Vala Ulmo, see that entry, ULMO, and POSEIDON.

NESSA One of Tolkien’s Valar, wife of Tulkas the Strong (the Valarian Heracles) and the sister of Oromë the Huntsman (the Valarian Orion the Hunter). She is most akin to the forest nymphs (dryads) of the Greco-Roman world, but among the Greek goddesses she most resembles Artemis (equated by the Romans with Diana), a deity associated with wildernesses and wild animals, most especially deer. Although Nessa is not a huntress like Artemis, both are “swift as an arrow” with the ability to outrun deer. Like Artemis, too, Nessa is also associated with dancing, liking nothing better than to dance on the evergreen lawns of Valimar.

NIBELUNGENLIED (THE SONG OF THE NIBELUNGS) The national epic of the German people, written by an anonymous poet around 1200 for performance at the Austrian court. The epic combines elements of myth with a real historical event. This was the catastrophic annihilation of the once-powerful German people, known as the Burgundians, in AD 436 by the Hun legions of Attila acting as mercenary agents for the Roman Emperor. The epic’s significance for the German people has been compared to that of the Iliad for the Greeks.

The Nibelungenlied is a tale of two halves. In the first part Siegfried, in order to win the hand of the Burgundian Princess Kriemhild, successfully helps Kriemhild’s brother, Gunther, king of the Burgundians, to woo the Icelandic warrior-queen Brunhild. Back in Gunther’s court, Brunhild develops a jealous rivalry with Kriemhild, which eventually results in Siegfried’s murder during a hunting expedition. In the second part, Kriemhild, now the wife of the king of the Huns, zealously plots her revenge. She invites her brother, sister-in-law, and the Burgundian vassals to her husband’s court. When a feud re-erupts, the resulting bloodbath ends with the death of all the main characters.

While Tolkien took inspiration from the primitive world of Germanic mythology generally, the world he creates in The Lord of the Rings has a closer affinity with the world of the medieval German knight Siegfried of the Nibelungenlied, than with that of his mythological counterpart, the heroic warrior Sigurd of the Völsunga Saga. In the Völsunga Saga gods and dragons mix comfortably with mortal heroes, while in the courtly world of the Nibelungenlied pagan gods and fantastic dragons have no real place. Siegfried’s early exploit of dragon-slaying take place offstage, as it were, before the beginning of the story. It is an event only talked about and appears as more of an ancestral rumor than a real event. The dragon appearing on the medieval battlefield in the Nibelungenlied would be as incongruous as the god Odin turning up as a guest at Siegfried’s marriage ceremony in Worms cathedral.

This is equally true of Aragorn and the courtly kingdom of Gondor in The Lord of the Rings. Such events as the slaying of dragons also take place offstage: either in the fairy-tale world of The Hobbit, or the genuinely mythic world of The Silmarillion. As with the Nibelungenlied, it could equally be said that Smaug the Dragon appearing on a battlefield in The Lord of the Rings would be as incongruous as the Valarian god Manwë turning up as a guest at Aragorn’s marriage ceremony in Gondor.

In the Nibelungenlied, a ring is the key to the epic’s tragic plot. Once part of the Nibelung treasure horde, at the time of the beginning of the story it is worn by Brunhild. Siegfried (in the guise of her husband, Gunther) takes it from her after wrestling her into submission and rapes her on her and Gunther’s wedding night. He gives the ring to his wife, Kriemhild, who later uses it as evidence to Brunhild that she has been deceived and that she is little better than Siegfried’s concubine. This humiliating revelation unleashes the subsequent tragedy.

The malevolent One Ring, too, unleashes tragic events, such as the death of Isildur while crossing the Anduin, or the temptation and death of Boromir. Just as the Nibelung ring ultimately seals the fate of all in the Nibelungenlied, just as surely does the One Ring seal the fate of all in The Lord of the Rings.

Interesting, too, is the Nibelung ring’s association with invisibility. To deceive and overcome Brunhild, Siegfried makes much use of the Tarnkappe, the cloak of invisibility he won by wrestling with the dwarf Alberich. In Tolkien’s works, the motifs of the ring and the cloak of invisibility are amalgamated: once worn, the One Ring causes the wearer to become invisible. Like Siegfried, Bilbo Baggins uses the power of invisibility to deceive and outmaneuver his enemies.

NIDHOGG A “flying dragon, glowing serpent” described in the Norse text known as Völuspá. Meaning “malice striker,” Nidhogg is the terrifying winged, fire-breathing monster that emerged from the dark underworld of Niflheim described in one account of the disastrous Battle of Ragnarök, which brought an end to the Nine Worlds of the Norsemen. Nidhogg’s ravening majesty in Ragnarök appears to result in similar disastrous consequence to that of Tolkien’s Ancalagon the Black (the Winged Fire-drake), which loosed such terrible withering fire down from the heavens in the Great Battle of the War of Wrath. In the Prose Edda account of Ragnarök, we have Jörmungandr the World Serpent, another dragonlike monster. Jörmungandr rose up with the giants to do battle against the gods and bring about the destruction of the World. In this version of Ragnarök, the god Thor (associated with thunder) appeared in his flying chariot. Armed with Mjölnir, his hammer, Thor slew Jörmungandr. In Tolkien’s Great Battle, the hero Eärendil appeared in Vingilótë, his flying ship and, armed with the Silmaril, slew Ancalagon.

NIENNA In Tolkien’s pantheon of Valar, the sister of Lórien and Mandos, known as “The Weeper.” She lives alone in the west of Valinor where her mansions look out over the sea and the Walls of Night. Her chief concern is mourning, and her tears have the power to heal and fill others with hope and the spirit to endure. She is comparable to the Norse Hlín the Shelterer, the goddess of mourning, grief, and consolation, as well as to the Greek Penthos (and the Roman Luctus), the personification of grief and lamentation. Nienna, also named Lady of Mercy, has a powerful counterpart in the Virgin Mary, as Queen of Heaven and Our Lady of Sorrows, respectively.

NJORD Norse god of the sea and seafaring. He is comparable to Tolkien’s Ulmo, the Lord of Waters, whose rise from the deep is announced by the sounding of the Ulumúri, his great conch-shell horn. Ulmo’s close association with Middle-earth, and his friendliness toward its peoples, may reflect Njord’s popularity among the seafaring Nordic peoples.

Noldor Elves

NOLDOR The Second Kindred of Elves who undertake the Great Journey over the wilds of Middle-earth, led by their lord Finwë, and eventually cross the Western Sea to the immortal land of Eldamar (“Elven-home”). In the High Elvish language of Quenya, Noldor means “knowledge.” However, we know that these Elves were originally to be called Gnomes (and indeed were still thus called in early editions of The Hobbit). Tolkien derived the term, not from the creatures of folklore, but from the Greek word gnosis, also meaning “knowledge.”

The Noldor are accordingly the “intellectuals” among the Elves, associated with arcane knowledge, as well as the greatest craftsmen. As jewel-and metalsmiths and pupils of Aulë the Smith, the Valarian equivalent to the Greek smith god Hephaestus (Vulcan), the Noldor vie in skill with the Dwarves. Their characteristic brilliance and hubris are encapsulated in the figure of Fëanor, who has some connections with Greek craftsman heroes, such as Daedalus and Prometheus.

NORSE MYTHOLOGY The myths and legends of the Norse people found in a rich body of medieval texts, principally such Old Norse poems as the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, and such Icelandic sagas as the Völsunga Saga.

These myths and legends provided a deep and enduring source of inspiration for Tolkien in all of his creative works. The influence can be traced not only in specific motifs (e.g., the multiple “worlds” as in Midgard/Middle-earth, Agard/Valinor), characters (e.g., Sigurd/Túrin Turambar), races (e.g., dwarfs/Dwarves), monsters (e.g., dragons), and artifacts (e.g., swords, rings, hunting horns) but in the ethic of stoic fatalism and stubborn code of personal honor shared by most of Tolkien’s heroes and, in The Silmarillion especially, a wild and dark sense of doom.

The influence is at its clearest, as with Greco-Roman mythology, in Tolkien’s pantheon of “gods” and “goddesses,” as can be seen in the chart on page 450. There are important differences between figures that superficially appear to be “counterparts,” and, in some cases, the differences are very wide indeed as in the respective rulers of the underworld. Hel, a frightening goddess whose subjects are those who died of sickness and disease, is a very different figure to Mandos the Doomsman, the stern but benign Lord of the Halls of Awaiting, who is rather more closely aligned with the Greek Hades. Likewise, there is no counterpart in Tolkien for the important goddess Freya, as goddess of love, sexuality, and fertility; Frey, fertility god; Thor, the thunder god; or Týr, god of war.

Odin is the most complex of the Norse gods and as such had an especially wide-ranging influence on Tolkien. Aspects of his ambivalent character can be found in figures as diverse as Manwë, Morgoth, Gandalf, and Saruman.

NORSEMEN Germanic people of Scandinavia of the early Middle Ages, famous as seafarers and settlers, known as Vikings (“pirates”), and feared during their great age of conquest from the late eighth century to the middle of the eleventh. Their language (Old Norse), literature, and mythology were Tolkien’s richest source of inspiration for his legendarium.

Most specifically, as a race or people, the Norse, in all but their skill in seafaring, provided the historic model for Tolkien’s Dwarves of Middle-earth. Both are proud races of warriors, craftsmen, and traders, stoic and stubborn, admiring of strength and bravery, and greedy for gold and treasure.

NORTHMEN OF RHOVANION Inhabitants of the region to the east of the Misty Mountains, and, according to Tolkien, a “better and nobler sort of Men” who were kin to the Edain of the First Age. They are shown as largely uncorrupted and, in the Third Age, remain “in a simple ‘Homeric’ state of patriarchal and tribal life.” Rather than being archaic Greek in character, as Tolkien seems to suggest here, they are in fact very like those men celebrated in the early Anglo-Saxon epic poetry the author so dearly loved.

Sunrise on Númenor

Númenórean king

The Northmen of Rhovanion, or “Wilderland” as this vast region is more often called in the pages of Tolkien’s fiction, are essentially the heroic forebears of Beowulf who made their home for millennia in Europe’s trackless forests, mountains, and river vales. Rhovanion was intended to resemble what the ancient Romans called Germania, the great northern forest of Europe. Tolkien also gives them a wild eastern frontier comparable to the Russian steppes. Just as the Roman Empire and their sometime Germanic allies faced wave after wave of Hun, Tartar, and Mongol invaders, so the Dúnedain of Gondor and their Northmen allies faced the recurring attacks of Easterling, Balchoth, and Variag invaders.

In the Northmen of Rhovanion we see something of the German tribes at their earliest stages of migration. They are a noble people who do not greatly diminish the forest or plow up the plains, and have only a few large, substantial towns and villages (such as Esgaroth and Dale). Among the many peoples dwelling in Rhovanion were those later known as the Beornings and Woodmen of Mirkwood, as well as the Bardings and the Men of Dale. However, one other people Tolkien “discovered” in the Vales of Anduin became a particular favorite. These fictional people are called the Éothéod, linked in Tolkien’s mind to the historic Germanic nation of horsemen known as the Goths.

NÚMENOR The large island in the Western Sea gifted to the Men of Beleriand by the Valar as reward for their part in the wars against Morgoth in the First Age. Ruled by a dynasty of kings descended from Elros, son of Eärendil, it flourishes for much of the Second Age but is ultimately destroyed, sinking back beneath the waves. In Númenor, we see a great civilization corrupted by power and pride slowly evolve into a tyranny that threatens the peace of the world and finally self-destructs.

Númenor is the most obvious example of the influence of the legends of the ancient Greeks on Tolkien’s fiction. His tale Akallabêth (“The Downfall of Númenor”) is Tolkien’s reinvention of the ancient legend of Atlantis, related by the Greek philosopher Plato in his dialogues Timaeus and Critias. Atlantis, another island set in a western sea (in this instance the Atlantic), is portrayed as a lost utopian civilization that the gods eventually destroy because of the pride and folly of its people.

Like the myth of Atlantis, Númenor is a cautionary tale of the rise and fall of empires, a common trope since classical times. Not even the greatest civilizations last because pride and power ultimately corrupt. Every rise to power is inevitably followed by a fall and subsequent self-destruction. This is often due to the tragic flaw the Greeks called hubris, a combination of excessive pride, overconfidence, and contempt for the gods. The fall of Tolkien’s Númenor is exactly of this kind. The last king, Ar-Pharazôn, in his contempt for the Valar and desire for immortality, leads a fleet against Aman, prompting Eru the One to cause the Change of the World: Arda is turned from being flat into a globe, and Númenor sinks beneath the waves. The event is also somewhat akin to the biblical second Fall of Man in the Great Flood.

Goldberry. Goldberry is the nymph-like daughter of the River-woman and the spouse of Tom Bombadil.

There may have been a more contemporary allusion to Tolkien’s history of Númenor. Christopher Tolkien suggests that his father’s portrait of the decline of Númenor into a militaristic tyranny with imperial ambitions was an implicit comment on Nazism.

NYMPHS In Greco-Roman mythology immortal nature spirits often associated with natural features of the landscape, such as a spring, grove of trees, or the sea. They were often categorized. For example, Naiads were water nymphs, Dryads were wood nymphs, and Nereids were sea nymphs. They were usually thought of as young beautiful women, most often benevolent, and the object of local cults. However, in mythology they could also show a more dangerous side, as when Naiads take the youth Hylas down into a pond as their companion.

In Tolkien’s world the influence of the Greek nymphs in their kindly aspect is most obviously seen in the figure of Goldberry, the “River-woman’s daughter,” but also more widely and loosely in Valar such as Nessa, Maiar such as Uinen, and Elves such as Lúthien.

OO

Young Orc Fighting a Scorpion

OATHBREAKERS, THE Wraiths of pre-Númenórean Men of the White Mountains who haunt the Paths of the Dead. Also known as the Dead Men of Dunharrow, these legions of ghostly warriors are the spirits of Men who swore allegiance to Isildur, king of the Dúnedain, at the time of the Alliance of Elves and Men, but who broke that oath and betrayed him to Sauron. Thereafter all the warriors of the Men of the White Mountains were cursed and known as the Oathbreakers: tormented terrible wraiths that haunted the labyrinthine mountain paths of Dwimorberg.

Tolkien’s Oathbreakers were in good part inspired by the many Norse and Germanic myths and real-life histories relating to broken oaths of fealty between warrior and lord, or oaths of alliance between king and king. For the peoples of northern Europe (as elsewhere), such oaths were legally binding. Oaths sworn upon weapons or oath rings were considered sacred trusts, and violation of those oaths had both real world and spiritual consequences. There was a belief that false oaths—sworn upon a sword—animated that sword, which became like an avenging entity that thirsted for blood and could be appeased only by the offender falling upon it. In Norse and German society, murder and manslaughter were not considered illegal offenses so long as they were carried out “honestly” and in the open, with the opponent given fair warning and the ability to defend himself. However, oath breaking was the most heinous of crimes, as it threatened the entire social order and hierarchy. This was especially true if the oath was broken for cowardly reasons, such as refusing the call to arms in the midst of battle, as was the case of the Men of White Mountains.

In the real-world honor code of these warrior societies, once an oath was broken, the offender would be banished and become an outlaw cast out of society. As an outlaw, he was beyond any lord or king’s protection. He could be hunted down and, if caught, could legally be hanged: the most shameful of deaths that made entry into the afterworld Valhalla impossible. Like the Dead Men of Dunharrow, in Norse and Icelandic myths and sagas, oathbreakers are frequently trapped in a terrible limbo world, at least until some means of restitution might be discovered.

In Tolkien’s tale, the curse is only lifted from the Oathbreakers after more than three millennia, when Isildur’s Heir appears at last in the Paths of the Dead. Aragorn, son of Arathorn—the rightful heir and king of the Dúnedain—summons the Dead to fulfil the oath they broke long ago. This Shadow Host manifests itself in a mighty battalion of ghostly warriors that, at Aragorn’s command, drive the Corsairs of Umbar from their fleet. Thus the souls of the Sleepless Dead are at last redeemed as the great pale army fade like a mist into the wind.

The Dead Men of Dunharrow

ODIN In Norse culture, the king of the gods, Odin is one of the most complex and ambivalent figures in any mythology and perhaps one of the single most important sources of inspiration for Tolkien in the creation of some of his leading protagonists. Through Odin’s many and diverse manifestations (as a god associated with battle, death, kingship, sorcery, poetry, and healing) we can trace his influence in such contrasting pivotal characters as Manwë, king of the Valar, and Gandalf the Grey, on the one hand, and Melkor/Morgoth and Saruman the White, on the other.

The beneficent, most godlike aspects of Odin come to the fore in Manwë, king of the Valar. He, like the Norse god, surveys the world from a high seat, sends out birds as his messengers or “eyes” (though Odin’s birds are the ravens Huginn and Munnin, as against Manwë’s Great Eagles), and has associations with poetry. In The Book of Lost Tales the Valar are described as having a “splendour of posey and sing beyond compare.” Appropriately enough, one of the Maiar belonging to Manwë, Gandalf, also has characteristics similar to Odin’s. Like the Norse God, he appears as a gray-cloaked, bearded wanderer, and has many names (“Many are my names in many countries …”). He also has the habit of turning up unexpectedly, and—on his journey from Isengard to Minas Tirith—rides a horse, Shadowfax, of wondrous powers and possibly divine origin, much like Odin’s steed Sleipnir.

The darker, necromantic aspects of Odin’s persona most obviously emerge in Sauron, aspects that clearly fascinated Tolkien who in his essay “On Fairy-Tales” wrote of “Odin the Goth, the Necromancer, Glutter of Crows, God of the Hanged.” Odin, the sorcerer king, rules the Nine Worlds of the Norse universe through possession of the magical power of a Draupnir (“Dripper”), a gold ring that drips eight more gold rings every nine days, a possession that, quite literally, makes Odin a “Lord of the Rings.” One possible source for the “Eye of Sauron”—the form in which Sauron almost exclusively manifests in The Lord of the Rings—lies in Odin’s own single eye, the other having been sacrificed in exchange for one deep draft from Mímir’s “Well of Secret Knowledge.” Thereafter, Odin (like Sauron) was able to consult and command wraiths, phantoms, and spirits of the dead.

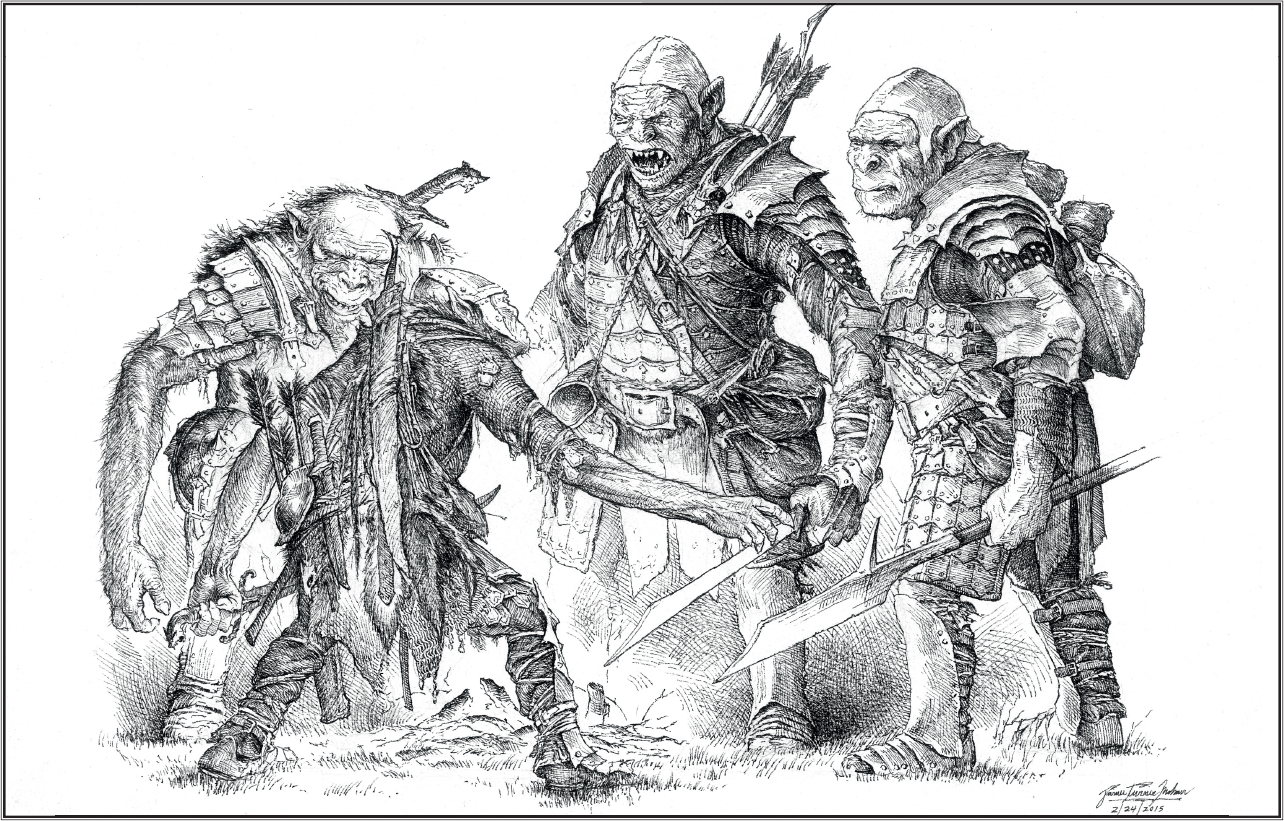

Orcs Debate. Violence, rather than reason, is the usual tool of an Orc who wishes to win an argument.

In Saruman the White, who ultimately becomes an echo of Sauron, there are also echoes of the necromancer god Odin. Saruman’s use of the palantír, in the tower of Orthanc to view distant places, recalls not only Odin’s high seat Hlidskjalf, but also Odin’s grim use of the severed head of Mímir to find out the secret knowledge of the Nine Worlds.

Oliphaunt. Into the Hobbit lands of the Shire creep many legends about the mysterious lands that lie far in the south of Middle-earth. Most fascinating to the Hobbits are the tales of giant Oliphaunts: tusked war beasts with huge pounding feet.

OLYMPUS The home of the gods of ancient Greece where Zeus, king of the gods, is enthroned and holds court. Olympus is both a real mountain and a mythological place. At nearly 10,000 feet, it was the tallest mountain in the Greek world and an obvious inspiration for Tolkien’s Taniquetil, the highest mountain in Arda where Manwë, the king of the Valar and Maiar, is enthroned and holds court.

OLWË The younger brother of Elwë, the king of the Teleri in Aman, and the founder of the port cities of Avallónë and, later, Alqualondë, the “Haven of Swans.” For his possible associations with the Avalon of Arthurian legend, see AVALLÓNË.

OLWYN The eponymous heroine in the medieval Welsh legend Culhwch and Olwen (one of the tales collected in The Mabinogion). She is considered the most beautiful woman of her age. Her eyes shine with light; her skin is also as white as snow. Olwyn’s name means “she of the white track,” a name she earns because four white trefoils spring up on the forest floor with every step she takes. She appears to be the very embodiment of the enchanting “lady in white” so often found in Celtic legend.

In Middle-earth, Olwyn appears to have partly inspired one of Tolkien’s greatest heroines, Lúthien Tinúviel, meaning “maiden of twilight,” the daughter of Elu Thingol, the high king of the Grey Elves, and his queen, Melian the Maia. Like Olwyn, she is dark-haired with snow-white skin, and is considered the most beautiful child of any race. Olwyn’s “white track” of trefoils finds an echo in the niphredil, a white star-shaped flower that first blooms on Middle-earth in celebration of Lúthien’s birth and which later grew on her burial mound. Furthermore, the winning of Olwyn’s hand required her suitor, Culhwch, to undertake the near-impossible quest of the “Thirteen Treasures of Britain.” This is certainly comparable to the near impossible Quest for the Silmaril, as the price for Lúthien’s hand was acquiring one of the three Silmarils in the Iron Crown of Morgoth, the Dark Enemy.

“ON FAIRY-STORIES” An essay on “fairy stories” first published in 1947 but which in origin was a lecture given in honor of the Scottish folklorist Andrew Lang (1844–1912) in 1938.

In the essay Tolkien attempts to define the fairy tale as different from other kinds of fantastic literary creations such as travelers’ tales (Gulliver’s Travels), Gothic novels (Frankenstein), and science fiction (many of the novels of H. G. Wells). A good fairy tale, he argues, creates a serious, consistent “otherworld” (which he called Faerie) that is “true” on its own terms. Such an otherworld offers the reader not only escapism and possible moral insights into the real world (both worthy goals in themselves) but also, and more importantly, a glimpse of joy. Pivotal to this feeling of joy is Tolkien’s concept of the “eucatastrophe,” or happy ending: “In such stories, when the sudden turn comes, we get a piercing glimpse of joy, and heart’s desire, that for a moment passes outside the frame, rends indeed the very web of story, and lets a gleam come through.”

Tolkien’s essay is a key moment in the evolution of his life as a writer and in the creation of Middle-earth, offering a justification of the genre of fantasy writing of which he, along with his friend and fellow Inkling C. S. Lewis, was a pioneer. The Lord of the Rings (1954–5) is in many ways the embodiment of the ideas he set out in “On Fairy-Stories.”

See also: RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY

ONE RING, THE

See: RINGS OF POWER

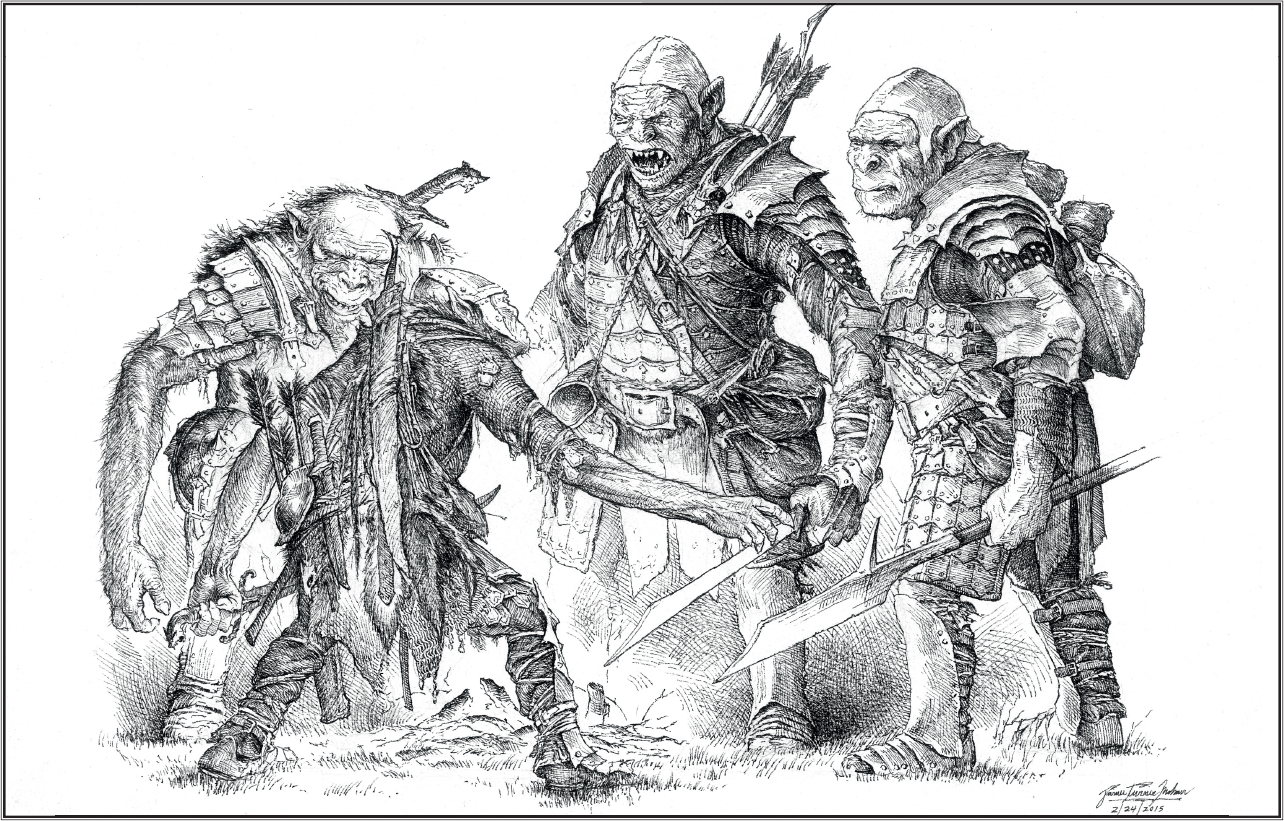

ORC The evil, goblinlike soldiers of the Dark Lords Morgoth and Sauron in Middle-earth. Tolkien’s Orcs originate in the early First Age when Melkor captures many of the newly awakened race of Elves, then takes them down into his fortress dungeons of Utumno (and later Angband). There, he tortures and transforms them into a race of slaves and soldiers who are as loathsome as the Elves are fair. The Orcs are hideous, stunted, and muscular with yellow fangs, blackened faces, and red slits for eyes.

Oromë finds the Lords of the Elves

Orc

Tolkien’s Orcs appear, like so many of his races, to have multiple sources of inspiration. In Beowulf, mention is made of orcneas (ironically in juxtaposition with ylfe—elves) as being among the “evil broods.” The word perhaps suggests “walking corpses,” like living dead, or zombies, the component word orc perhaps deriving from the Latin word Orcus, an Etruscan and Roman god of the underworld and for the underworld itself. However, in a letter, Tolkien wrote that he himself doubted this derivation. The word “orc” also appears in sixteenth-century English to mean a devouring monster, while the man-eating ogres of fairy tales are another, related breed.

So much for the etymological inspirations. The concept and nature of Orcs, as demonic underlings programmed to do the bidding of their evil masters, has resonance with numerous myths and tales from around the world. Such demons are prominent, for example, in the Old Testament where demons are considered innumerable (and often invisible), preferring to live in isolated, unclean places such as deserts and ruins, and greatly to be feared, especially at night. In all of Tolkien’s descriptions of Orcs, they, too, create a sense of vast anonymous numbers and are likened to innumerable swarms or devastating black waves. They come pouring out of caverns with impersonal, insectlike inexorability and are often compared by the author to flies or ants.

Further comparisons with a large number of mythological and legendary monsters can be made, from goblins (indeed, the name more often used for them in The Hobbit) to kobolds to the golem.

OROMË The huntsman of the Valar who loves to ride his white horse, Nahar, through the forests of Middle-earth as he hunts down the evil creatures of Melkor/Morgoth. Oromë’s name means “horn-blower,” and the sound of his horn, Valaróma, is a terror to all servants of darkness. The Sindarin name for Oromë is Araw.

It is fairly certain that Tolkien’s inspiration for Oromë was Arawn the Huntsman of Welsh mythology, the ruler of Annwn, an otherworld of youth and pleasure. Like Araw/Oromë, Arawn rides like the wind with his horn and hounds through the forests of the mortal world. In one Welsh legend, found in The Mabinogion, Arawn causes Pwyll, lord of Dyfed, to leave his own realm and dwell in Annwn for a time. Tolkien’s Oromë befriends three Elven kings at Cuiviénen and acts as their guide to the immortal Undying Lands of Aman.

ORPHEUS In Greek mythology, the hero-cum-musician who can charm all living things, and even stones, with his singing and lyre-playing. The key myth associated with him is his descent into Hades to rescue his dead wife Eurydice, and his ultimate tragic failure.

Tolkien himself acknowledged that the ancient Greek love story of Orpheus and Eurydice provided the framework for his love story of Beren and Lúthien Tinúviel in The Silmarillion. Both Tolkien’s tale and the Greek myth concern a descent into the underworld and the power of love and music in the face of death.

In Tolkien’s adaptation, however, the male and female roles are reversed. In the Greek myth, Orpheus plays his lyre and sings to make the hellhound Cerberus fall asleep before the gates of Hades. Once within them, he again sings such beautiful songs that Hades weeps and grants him the life of Eurydice, on the condition that as the husband and wife make their way out of the underworld he does not look at his wife. In Tolkien’s version, it is Lúthien who sings and makes the wolf-guardian Carcharoth fall asleep before the gates of Morgoth’s dark subterranean fortress, and who, once within, yet again sings such beautiful songs that the entranced Morgoth falls into a slumber, enabling Beren to cut one of the Silmarils from his iron crown.

Orpheus fails in his quest at the last moment. Leading Eurydice up to the world of the living, he is unable to resist turning back to look at her and she is instantly returned to Hades. Beren and Lúthien’s fate is not quite so tragic. Just as they are about to escape Angband, Beren is attacked by the now wide-awake Carcharoth. The wolf-guardian bites off Beren’s hand holding the Silmaril. The prize at the last moment is lost, though Beren is later healed on the lovers’ return to Doriath.

OSSË Maia spirit of the sea who serves the Vala Ulmo, Lord of Waters. Tolkien’s Ossë bears some resemblance to Aegir in Norse mythology, a jötunn associated with the ocean, as well as to other minor sea deities in Greco-Roman mythology, such as Proteus and Glaucos. Ossë, like Aegir, is subject to wildly shifting moods and is portrayed as overly fond of whipping up storms and squalls. However, he is also friendly toward the Elves, especially the Teleri.

OXFORD City in southern England, home to the English-speaking world’s oldest university, where Tolkien was at first an undergraduate student (1911–15) and then a professor of Anglo-Saxon/English literature at two of the colleges (1925–59). For Tolkien, who fought in one world war and lived through another, Oxford was a refuge of learning and wisdom in the middle of a world gone mad with the slaughter of conflagration.

Tolkien once described the northwest of Middle-earth as being geographically equivalent to Europe and that his Elven refuge of Rivendell was “taken (as intended) to be at about the latitude of Oxford.” However, it is quite apparent that Rivendell was not just “on the latitude of Oxford”—it was an analogue for Oxford itself. Rivendell was the Elven refuge of Elrond Half-elven and his people. Considered the “Last Homely House East of the Sea,” for 4,000 years Rivendell (or Imladris in Sindarin) was a refuge of wisdom and great learning for all Elves and Men of goodwill. In Rivendell, the common tongue was Westron, while the true scholar’s choice was the ancient Elvish languages of Sindarin and Quenya. In Oxford, the common tongue was English, while the true scholar’s choice was the ancient languages of Latin and Greek. Master Elrond’s use of language may be somewhat archaic, but not excessively so for someone who is essentially a 6,000-year-old living version of the Ashmolean Institute and Bodleian library combined.

PP QQ

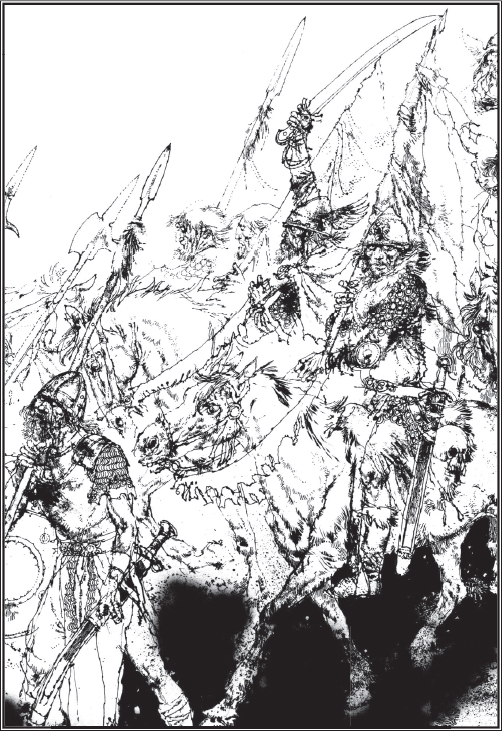

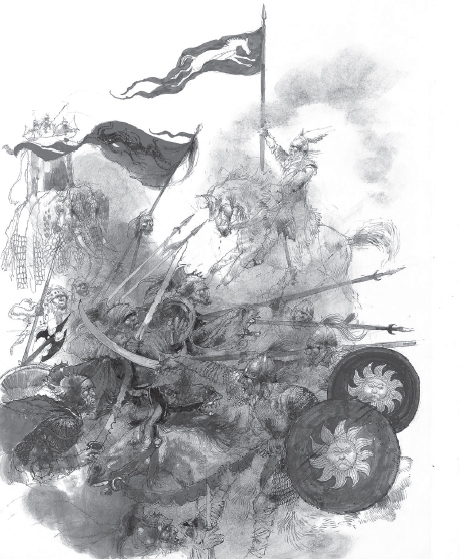

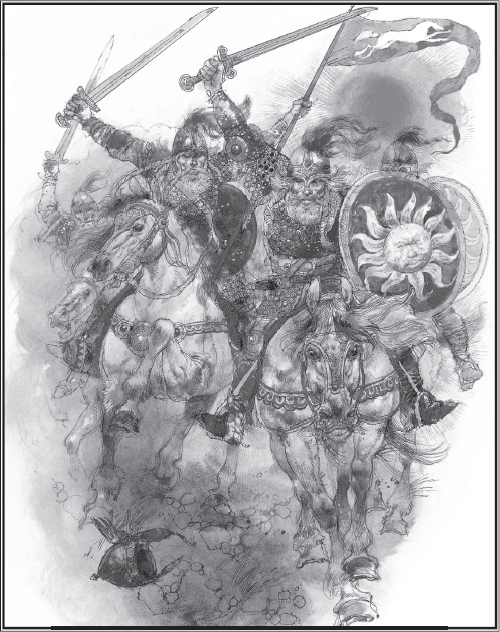

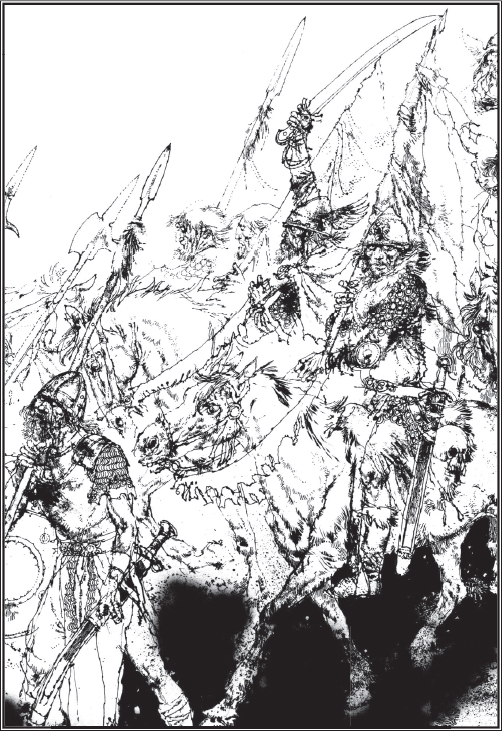

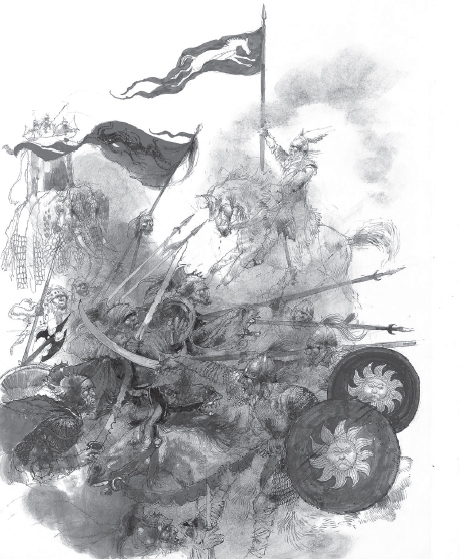

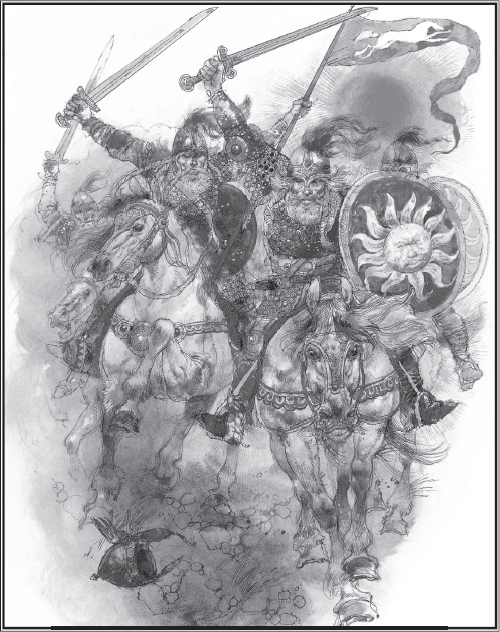

The cavalry charge of the Rohirrim at the Battle of Pelennor Fields

PARADISE LOST Epic verse narrative by the English poet John Milton (1608–74) about the Old Testament “war in heaven” in which Lucifer/Satan leads an army of rebel angels against God, only to be defeated and hurled down into hell. While there are many aspects of Tolkien’s world that differ greatly from Milton’s great Christian epic, it influenced Tolkien—especially in his Ainulindalë and Valaquenta—not only in terms of its grand narrative themes but also in sublime (“Miltonic”) literary style.

In Tolkien, it is Melkor/Morgoth who rebels against Eru Ilúvatar in the Timeless Halls. Just as Lucifer questions the ways of God, so Melkor asks why the Ainur (the angelic spirits serving Eru, who sing the world into being) could not be allowed to compose their own music and bring forth life and worlds of their own. This is the nub of Melkor’s complaint: he wishes to have freedom over his spirit and his own creations, just as Lucifer proclaims his desire to create things of his own in a manner equal to God.

Both Tolkien’s Melkor and Milton’s Lucifer seem heroic in their steadfast “courage never to submit or yield.” However, in truth, both rebel angels are primarily motivated by overweening pride and envy. It is worth noting how in Paradise Lost Satan’s minions “Towards him they bend / With awful reverence prone; and as a God / Extol him equal to the highest in Heav’n.” It is a description that is comparable to Melkor enthroned in his subterranean halls, and reveals the true motive of both antagonists: to become God the Creator themselves.

As Tolkien explains, Melkor’s fall is a moral one: “From splendour he fell through arrogance to contempt for all things [ … ] He began with the desire for Light, but when he could not possess it for himself alone, he descended through fire and wrath into a great burning, down into Darkness.” And so, Melkor—like Lucifer—brings corruption into the world. All evil in Tolkien’s world has its beginning in Melkor, although in his beginnings, like Lucifer, Melkor is not evil.

PATHS OF THE DEAD A terrifying underworld passage under the Dwimorberg in the White Mountains, haunted by the Dead Men of Dunharrow, Men cursed by Isildur after they failed to come to Gondor’s aid in the War of the Last Alliance. During the War of the Ring, Aragorn, out of need, is forced to take the passage and allows the Shadow Host to finally fulfill their oath.

In his famous cross-cultural study of religion and mythology The Golden Bough (1890–1915), the Scottish anthropologist James George Frazer (1854–1941) argues that rites of passage—such as a “descent into the underworld,” however this is defined—are found widely across the world as a necessary stage in the ascent to kingship. Frazer’s ideas were highly influential for much of the twentieth century and are discernible in the story of Aragorn, who, before he comes to Minas Tirith to be acknowledged as king of Gondor, must pass through a form of the underworld.

When Aragorn emerges, it is as the king of the Dead Men of Dunharrow, in command of a terrifying army of undead warriors against the Corsairs of Umbar. Like Jesus in the New Testament (for Frazer, an example of the “sacred king”), Aragorn has descended into “hell” to free the “imprisoned spirits” of the sinful dead.

PELENNOR FIELDS The site, beneath the walls of Minas Tirith, of the most richly described conflict in the annals of Middle-earth, and the most dramatic (if not the final) battle of the War of the Ring. It took place on March 15, 3019 TA.

In his unfolding of the battle, Tolkien draws on many aspects of real-world military history, ranging over some 1,500 years of European warfare. To begin with, many of Gondor’s opponents in the battle seem to have inspirations in the enemies of ancient Rome or Byzantium: The Mûmakil (Oliphaunts) are tamed and mounted by Haradrim. These creatures evoke the elephants ridden by Carthaginians at the Battle of Zama, fought between the forces of Hannibal and the Roman troops led by Scipio, in 202 BC. The fierce Variags of Khand appear to have been inspired by the Varangians of Rus’ who, in the ninth to eleventh century, launched a series of attacks on Byzantium. The Easterlings of Rhûn are likely inspired by the twelfth-and thirteenth-century Seljuk Turks of the Sultanate of Rûm in Anatolia, who harried and seized key Byzantine ports and other territories.

On the Gondorians’ own side we have the Rohirrim, whose cavalry charge is solidly based on a historical Gothic cavalry action in support of the Romans at the Battle of Châlons in AD 451. When all seems lost for Gondor, the tide is turned by the appearance of the black-sailed ships of the Corsairs, carrying reinforcements from Gondor’s coastal settlements, under the command of Aragorn.

PEREDHIL (“HALF-ELVEN”; SINGULAR: PEREDHEL) Term used to describe the offspring of Elves and Men, and encompassing, among others, Eärendil and Elwing, their twin sons, Elros and Elrond, as well as Elrond’s own offspring, notably Arwen. Most of the Peredhil are granted the choice of deciding which race—the immortal Elves or mortal Men—they wished to belong.

There may be a parallel in Greek mythology where many of the heroes are described as the children of immortal gods or nymphs and of humans. Thus Perseus is the son of Zeus, king of the gods, and the mortal Danaë, and Heracles is the son of Zeus and the mortal Alcmene. Occasionally, such offspring undergo apotheosis, as most notably in the case of Heracles, who, after his mortal death, rises to join Zeus on Mount Olympus. The Greek Dioscuri (the twins Castor and Polydeuces, one mortal, the other immortal) also provide a partial parallel with Elros and Elrond.

See also: CASTOR AND POLYDEUCES

PEREGRIN (“PIPPIN”) TOOK The youngest Hobbit member of the Fellowship of the Ring who, after his adventures in the War of the Ring, becomes Peregrin I, 32nd Thain of the Shire.