The little Russian island: the first castaways

Bloodhounds abroad

In the spring of 1902 when Lenin first set foot on British soil he was, of course, aware that he was by no means the first Russian political émigré to cross the English Channel. He was equally conscious of the fact that, wherever his compatriots gathered, there too one would be sure to find representatives of the tsar’s political police, the notorious Okhrana. Long before March 1854, when Britain declared war on the Russian Empire and signalled the commencement of two years of hostilities in the Crimea, the British public had been warned to be on the look-out for tsarist spies in their midst. As early as 1835, a few years after the suppression of the Polish uprising by Tsar Nicholas I, a letter appeared in the London Times drawing attention to a certain Russian spy by the name of Dombrowski who had tried to pass himself off as a Polish refugee and insinuate himself into the Polish émigré community in London. The correspondent continued:

The unrelenting and barbarous persecution which is carried on by the Emperor Nicholas against the unfortunate Poles who are within his reach is too well known; but the public are not so generally aware, that even the free soil of Great Britain cannot shelter the heroic men who have preferred exile to submission from the effects of his ruthless hate … Not satisfied with the wholesale persecution of the unfortunate Poles in their own country, he sends his bloodhounds abroad in search of individual victims.1

Such ‘bloodhounds’ were despatched to keep a close watch not only on exiles but also on any Russian subject who happened to find himself (or herself) in a foreign country, whether for business or pleasure. As one historian commented: ‘In the drawing rooms of London and Paris he [the travelling Russian] dreads that the eyes of the secret police may be upon him.’2 But, in particular, it was the publishing activities and political activism of the early London émigrés, such as Alexander Herzen (Gertsen) and Nikolai Ogarev which were the main concern of Tsar Nicholas’s Third Section (as his Secret Police Department was then known). Herzen himself recalled the perfidious activities of the Russian spy, G. G. Peretts, and told of how his own distribution agent Trübners had dismissed a Polish employee, following the discovery that the latter had been in direct correspondence with the Russian government.3 As the Daily News commented, ‘The necessity for vigilance against treachery and spies is obvious.’4 But although such reports and reminiscences might lead one to conclude that a tsarist agent lurked on every street corner of London, the reality is that, at this time, the British network of the Third Section probably comprised no more than a handful of individuals and, even with the assistance of diplomatic staff such as F. I. Brunnov,5 its operations in the British capital were disorganized: the bloodhounds did not hunt in packs, and were failing to return the results required of them.

Nicholas’s concerns with regard to the freedoms that Britain afforded such ‘political criminals’ were taken up on his succession to the throne by his son, Alexander II, whose eagerness to pursue his opponents beyond the borders of Russia would increase as his reign progressed and as the radical Party of the People’s Will began to adopt more direct means of protest. An indication of his anxiety was demonstrated in October 1878, when the Russian chargé d’affaires in London, M. F. Bartolomei, approached Lord Salisbury, then foreign secretary, to enquire, informally, whether the newly formed Criminal Investigation Department of the Metropolitan Police might consider releasing some officers to assist in ‘the watching of the refugees who congregate in London’.6 St Petersburg had received information that certain refugees in the capital were plotting the assassination of the tsar and they wished to be informed as soon as the assassins set off for Russia.7

Bartolomei’s request caused alarm both in the Home Office and at Scotland Yard, with the chief commissioner of the Metropolitan Police producing a memorandum on the subject that day, very much deprecating any direct communication between the Russian Embassy and the police, warning that such acts of political espionage were apt to cause ‘great animosity against the government among a large class of the people’, and advising that ‘any interference with the right of asylum in this country for political refugees is sure to arouse much feeling.’8 The Home Secretary Richard Assheton Cross agreed and, consequently, Bartolomei’s request was politely declined.9 It was clear to St Petersburg that the perceived threat from London would have to be tackled without the assistance of the British police.

The agentura

This was the way things stood until 1(13) March 1881 when Alexander’s reign was brought to an abrupt and bloody end (not, it should be added, from without his empire, but from within). As he drove alongside the Catherine Canal in St Petersburg, a bomb was thrown at his carriage killing a soldier and injuring the driver. As the dazed tsar emerged, another bomb was thrown, killing him instantly. His assailants, Nikolai Rysakov and Ignaty Grinevitsky, assisted by the young Sofiya Perovskaya, were all members of the radical Party of the People’s Will, and this act was the culmination of a programme of terror which they had commenced some two years earlier. The ensuing reaction to the assassination was extreme, with virtually all internal opposition being quickly crushed thanks, in large measure, to the uncompromising tactics of the notorious St Petersburg chief of police, G. P. Sudeikin. However, in so doing, ‘that most brazen-faced provocateur’ effectively created a rod for his own back by forcing even more revolutionaries abroad, thereby removing them from his immediate control and supervision.10

This new, self-inflicted problem had to be tackled and so it was that, soon, reports began to appear in the British press describing how the Russian political police had arranged to despatch agents to track Russian socialists in all the principal cities of Europe, and had plans to send four to London alone.11 However, it was not until two years later, in July 1883, that Russia finally decided to set up a permanent (and illicit) Foreign Agency (Zagranichnaia agentura) in their Paris Embassy at 79 Rue de Grenelle in the 7th arrondissement, from whence agents could be posted to any other European country, including Britain. The enterprise got off to a slow start due to incompetent management, but came into its own in the summer of 1884 with the appointment as head of Petr Ivanovich Rachkovsky, a former police informer.12 This protégé of Sudeikin was quick to put his stamp on the Agency. In an early letter to the Prefect of Police in Paris, Rachkovsky spelled out his intentions: ‘I am endeavouring to demoralize the radical émigré politically, to inject discord among revolutionary forces, to weaken them, and at the same time to suppress every revolutionary act in its origin.’13 It was his view that Russia’s problems lay not with Russians but with non-Russians, ‘Jews, Ukrainians, Poles and other inhabitants of Russian Lands’, and in the years to come he would provide yet more proof of these deep-rooted racist and anti-Semitic beliefs.

The new head of the Foreign Agency energetically set about developing close relationships with French police, politicians, publishers and journalists. As well as inheriting some Russian police agents of long standing such as Vladislav Milevsky he also, at an early stage, recruited another of Sudeikin’s pupils, Abram Landezen (real name Avraam Gekkel´man, later known as Arkady Mikhailovich Garting).14 The latter, who will reappear in later chapters, was described as follows: ‘age about 40, height 5 ft. 6 ins., complexion, hair and eyes dark, moustache dark, short, clean-shaved. Looks more a Frenchman than a Russian. Smart appearance, excitable demeanour.’15 At the same time, Rachkovsky branched out, recruiting new native operatives, such as former member of the Sûreté, Henri Bint. Together, these agents were responsible for wrecking a range of revolutionary enterprises throughout Switzerland, but perhaps their greatest and most successful joint venture played out in Paris in the spring of 1890 when, as a result of Landezen-Garting’s provocation, a group of Russian émigrés was arrested on charges of illegal possession of explosives. The trial resulted in six of the accused receiving sentences of three years imprisonment and, although the provocateur had smartly fled the scene before any arrests were made, the judge identified him as ringleader and, in absentia, handed down the maximum sentence of five years.

Following this affair, the attitude of the French government and public towards the émigré community cooled noticeably and, later that year, relations were dealt a final blow when the former head of the Russian police, General N. D. Seliverstov, was murdered in the heart of the French capital. The assassination, allegedly carried out by a Polish socialist agitator (although some suspected the hand of Rachkovsky himself), led to a series of expulsions and marked the end of Paris as a safe haven for the Russian political emigration. Now, thanks to a combination of a strengthening of the anti-émigré policies of the governments of Austria and Germany, and the ruthless efforts of Rachkovsky and Landezen in Switzerland, the revolutionary emigration found itself with almost nowhere else to turn but London. With his quarry thus conveniently corralled, Rachkovsky deemed it time to cross the Channel and to expand his operations into the British capital.

To London

In the course of the 1880s a handful of high-profile Russian revolutionaries such as Peter Kropotkin, Nikolai Chaikovsky, Vera Zasulich and Sergei Stepniak (Kravchinsky) had already sought refuge in England and had been sympathetically received by a small number of liberal-minded British men and women. (In due course, they would all, to a greater or lesser extent, come to be associated with the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom (SFRF) and the Russian Free Press Fund (Fond vol´noi russkoi pressy).) Now, in the early years of the new decade, a similar welcome was extended to the latest batch of arrivals, not all of whom had found their journey to London a straightforward one. Feliks Volkhovsky, a former member of Chaikovsky’s revolutionary circle, had been exiled to Siberia from whence he fled eastwards via Vladivostok and Yokohama. After a prolonged stay in Canada and America, he eventually arrived in London in the summer of 1890.16 His journey to safety, however, had not been as circuitous, nor indeed as perilous, as that of the young radical journalist Vladimir Burtsev who had had the good fortune to leave Paris in April 1890 only days before the mass arrest of his comrades in connection with the aforementioned bomb plot. He had intended to return to his homeland for propaganda and fund-raising purposes but realizing that he had been betrayed by Landezen, and that the Russian police were now in hot pursuit, he embarked on a remarkable catch-me-if-you-can journey which was followed anxiously by none other than Tsar Alexander III himself, who demanded that he be sent regular progress reports on the pursuit.17 The journey took the revolutionary through most of the countries of central Europe until he eventually found refuge on board a British steamship in the lower reaches of the Danube. Even then the Russian police refused to give up the chase and, accompanied by acquiescent Turkish officials, boarded the ship as it lay at anchor off Istanbul and demanded that Burtsev be handed over to them. It was only thanks to the bravery of the English captain, who steadfastly refused to surrender his charge, that Burtsev survived intact and arrived eventually to a hero’s welcome at Surrey Commercial Dock in London’s East End on 6 January 1891.18

It appeared, however, that the English capital was no longer able to provide the safety and anonymity that the revolutionaries so desired. On disembarkation Burtsev’s compatriots had spirited him off to what they confidently assumed was a safe, secret address in north London. However, within days the whereabouts of the new arrival had already been transmitted to St Petersburg, with Rachkovsky reporting that the fugitive was now to be found living with Volkhovsky at 130 St John’s Way, Upper Holloway, under the pseudonym Smith.19 It appeared that now the tentacles of the Okhrana had stretched into every corner of Europe. Indeed, earlier that month, The Times had claimed that the foreign section of the Russian Secret Police had recently been restructured and that eighty-four new agents had been added to the large staff which previously existed. According to this report, the central office continued to be in Paris, but sub-agencies had now been created at Zurich, Berne, Geneva, Mentone and Montpellier. In addition, it claimed, there now existed a London office which was controlled from Paris.20 Whether or not the agentura had indeed grown to such a size is open to question but there is absolutely no proof that Rachkovsky had commenced formal operations in London at this early stage. According to the Russian police archives it was not until the spring of that year that the agency chief crossed the Channel with the express intention of investigating the ‘establishment of a special surveillance unit’ in the British capital. To this end he had toured the haunts of the émigrés and held a meeting at the Russian Embassy with the chargé d’affaires, Butenev.21 As for the earlier information he had obtained concerning Burtsev’s address, this had not come into his possession via some agent on the ground in London but from a letter sent by Burtsev a few days after his arrival to an old associate in Paris who, unbeknownst to Burtsev, had gone over to the enemy and was now in the pay of the Okhrana.22

It was not until April 1891 that Rachkovsky met up in Nice with the Director of Police P. N. Durnovo,23 in order specifically to discuss the expansion of operations and arrange funding that would ensure surveillance in London could be carried out effectively.24 With finances secured, he was only then able to set about the recruitment of agents. Six months later he duly reported that his London agency was fully up and running, claiming even that he had already infiltrated an agent into the local emigration. ‘Now’, he declared, ‘all the London émigrés and all those who have dealings with them are under our complete control.’25 In fact, this was something of a hollow boast, for his first undercover agent, the unfortunate Polish émigré Bolesław Maliankewicz, had proved so incompetent and unsuited to the task that he had to be quickly removed from London before he could do any further damage to the agency.

Maliankewicz’s tale is a sad one. Born in Warsaw in 1867, he joined the ranks of the revolutionary opposition in his youth and in April 1884 gained a certain notoriety when he threw a bomb at Cracow police headquarters. In his own account of the affair, however, he neglected to mention that he had thrown the bomb at a window but missed, with the result that the device bounced back off the wall and blew up injuring no one but himself. The unfortunate bomber was immediately arrested.26 Much later, upon his release from prison, he left the country and settled in the heart of the radical emigration in London’s East End where he appears to have ‘lost the revolutionary faith’. In early 1891 he offered up his services as a spy to St Petersburg, saying he had gained the trust of Kropotkin, Lavrov, Stepniak, Volkhovsky and others in the London emigration associated with the journal Free Russia. Durnovo eagerly accepted and had Rachkovsky take him on at a salary of 200 francs a month.

But even as one reads the early communiqués, it is easy to detect a lack of balance in some of the spy’s judgements. In his report of one meeting, for example, he claimed that a particularly cruel stance was adopted by none other than the artist William Morris, whose public rejection of the violence of anarchism was already widely known at the time. It is evident too, from his derogatory comments, that Maliankewicz was driven by an excessively bitter personal hatred of an elderly and much-respected Polish émigré Stanislaw Mendelssohn – ‘mon mortel anatagonist’, as he called him. Then, in the letters that followed, a sense of panic and paranoid suspicion started to creep in. It soon became apparent that the new recruit was liable to do more damage to the Agency than good and it was therefore arranged for him to be transferred to Paris, where at least, he could be kept under closer control.

Sadly, the affair ended in tragedy. Maliankewicz’s file shows that for a number of years he lived on in Paris, quietly and in considerably straitened circumstances in an asylum for the poor. Then, in 1897, Rachkovsky received a query from St Petersburg concerning a report that his former agent had confessed to his fellow émigrés that he had been in the employ of the Okhrana and had then promptly shot himself. The head of the Foreign Agency replied with a brusque telegram, stating that the deceased had indeed worked for him for a time, that he was sacked because he was ‘useless’ and that he had committed suicide solely as a result of critical financial embarrassment. A vivid example of Rachkovsky’s callous indifference to the suffering of his fellow man, be he friend or foe.

Leaving aside his agent’s incompetence, Rachkovsky had been making strenuous efforts to win the cooperation of the British authorities and to gain an entrance to the British press but had failed on both counts. Following his successes in Paris, he was quite exasperated by his inability to recruit representatives of the latter to his cause and, in a report to St Petersburg, expressed his displeasure in an astonishing diatribe in which he referred to the British in general as ‘a self-seeking, dishonest nation whose sole objective, in combined agitation with our own revolutionaries, was the violent overthrow of the Supreme Power!’27

It is possible that Rachkovsky’s entire enterprise may well have crumbled before it got off the ground had it not been for a chance introduction he received to the chief inspector of the Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard, Mr (later, Sir) William Melville, an individual who bemoaned the ‘feeble’ attitude of his superiors towards the anarchist menace. He shared his Russian associate’s disdain of radicals of every description and was more than willing to help the latter sweep them out of the country.28 The exact degree to which the two policemen collaborated at this early stage in their relationship is open to question but it is doubtless thanks to Melville that the doors of Fleet Street were finally opened up to the Russian policeman. He, in turn, did not hesitate to make use of the opportunity, sending off defamatory articles on Stepniak and the other émigrés to compliant newspapers such as the Daily Mail and Morning Advertiser.29

Now that fortune appeared to be smiling on him, the head of the Foreign Agency did not rest on his laurels. He wrote to St Petersburg requesting, and immediately receiving, a payment of 10,000 francs to enable him to employ another sixteen surveillance agents in Europe.30 How many of these were intended for service in London is unclear, although it is known that Rachkovsky considered his operations in the British capital – ‘the second most important centre of sedition after Paris’31 – to be important enough to warrant the dispatch of one of his most trusted and longest-serving spies, Vladislav Milevsky, ‘to collaborate with the London police’. Evidently, Chief Inspector Melville’s unofficial assistance to his Russian colleague extended further than merely putting him in touch with his friends in the press: he was willing even to offer up the services of his own staff at Scotland Yard.

At the Museum

Towards the end of the nineteenth century the round Reading Room of the British Museum had come to resemble a veritable club of international revolutionaries whose Russian contingent included the likes of Kropotkin, Chaikovsky, Stepniak and, of course, Burtsev.32 The Museum archives, as well as providing ample proof of the popularity of the Library amongst the Russian community, also point to the presence in the Reading Room of other individuals, both English and Russian, whose primary purpose for admission was certainly not that of self-betterment, but rather the covert surveillance of the émigrés at their academic labours. In December 1893, the principal librarian received a letter from young Police Constable Francis Powell of the Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard requesting admission to the Reading Room. He did not require it ‘for the ordinary purpose’ but, as he explained, in order to keep an eye on ‘certain persons not above suspicion’ who frequented the rooms. He added that he did not wish to disclose his identity for fear of arousing the suspicions of the suspects.33 The Museum authorities evidently had no moral objection to the request and a reader’s ticket was immediately made available. Some years later, Powell was himself recruited into the Okhrana as head of its operations in England, and one might therefore safely infer that at this time, like his superior, Chief Inspector Melville, he too had already formed close links with Rachkovsky and that the ‘certain persons’ he had in mind were members of the Russian émigré community.34 Soon afterwards, Powell arranged the admission of another of his colleagues, Detective Sergeant Michael Thorpe who, it is worth noting, actually preceded his associate as the Okhrana’s contact in London and who, on his retirement, was even awarded a pension by the Russian Department of Police.35 It is almost certain that he too, by the time he entered the Reading Room, was already in regular contact with agent Milevsky in London.

But Rachkovsky was not content to rely solely on the external surveillance provided by Melville’s men, nor on the services of the ageing Milevsky: it was essential to have his own man on the inside and he therefore called into action one of his recent young Russian recruits, Lev Dmitrievich Beitner, who arrived in London from the University of Zurich in August 1894. Having previously struck up friendships with Volkhovsky and Burtsev, Beitner immediately immersed himself in the life of the émigré community, quickly gained admission to the British Museum – thanks, curiously, to a letter of recommendation from none other than the principal librarian himself, Richard Garnett – and began to ingratiate himself with a number of other members of the Russian Free Press Fund and their British supporters. With his agent firmly in place Rachkovsky could now, more confidently, repeat the claim made three years earlier, that all the London émigrés were under his complete control. And as we shall see, the strenuous efforts he had made to this point would soon bear fruit, playing out in a dramatic denouement under the very dome of that famous Reading Room.

Teplov and the Free Russian Library

It was not only the British Museum that needed to be surveilled but also another émigré meeting place which perhaps posed an even greater threat to the Russian state. This was a small, insignificant library which had recently been founded in the heart of the East End. The library’s location in Whitechapel, one of the poorest slum areas of the capital, was anything but welcoming – as one visitor described:

The neighbourhood wаs dreadful. Public houses at every step, drunks swearing everywhere. Street-sellers filled the pavements, with tramps, pickpockets and swindlers scurrying hither and thither, hanging on to their women who were dressed in rags and wearing wooden shoes on their bare feet. Somewhere, another fight broke out. The undisguised miserable poverty hid neither its ulcers nor its vices.36

The journalist Isaak Shklovsky, in one of his silhouettes of London life, left an evocative description of what visitors at the turn of the century would have encountered during their visit to the library’s premises at no, 16 Whitechapel Lane, E1. It is worth quoting here at length:

They arrived at a rickety-looking house, the wall of which was bellying out. Above the door hung a blue notice board with the sign ‘Russian Odessan Restaurant’ which also carried an inscription in Yiddish to the effect that the food was kosher. Below this sign was another which read Russkaia Bezplatnaia biblioteka (Russian Free Library). The entrance was anything but inviting. They had to grope their way along a dark corridor which stank of cabbage and fried fish, emanating no doubt from the restaurant. Then they had to climb a staircase which presented a dangerous ascent. Not only had someone poured dishwater down it, but many of the banisters were missing, taken, no doubt, by the poor to feed their stoves during the bitterly cold nights. On each landing were doors giving on to filthy little workshops inhabited by cobblers and tailors.

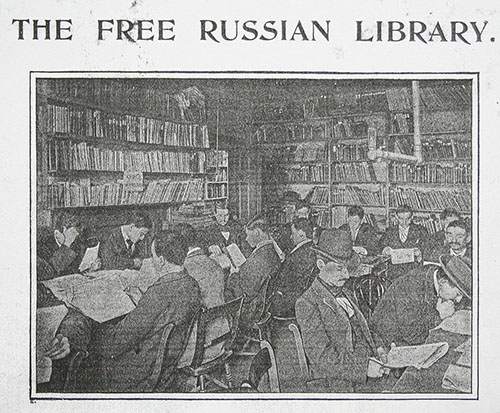

The library itself, which survived solely on donations from the poor inhabitants of the area, made a disheartening impression. Everything carried the imprint of desperate poverty, or rather, destitution: the sad little tables, the rough benches and, in particular, the huge numbers of members of the public burrowing in newspapers and books (see Figure 1). Most were unemployed, poorly dressed, pale and, in all likelihood, starving, as they silently leafed through the pages of the Russian and Jewish newspapers on offer. Along the walls, rows of books were arranged on shoddily-built, home-made bookcases. For the library’s visitors, in this distant foreign land, these books represented a precious memento of their homeland. These poor unfortunates, driven from the ghetto by extreme poverty and sometimes by terrible bloody catastrophe, lived and breathed the memory of their homeland and cherished its language, even though most of them did not have a particularly strong command of it.

A door lead from the large room into a smaller one which was even filthier and stuffier, piled up to the ceiling with books and dusty bundles of old newspapers. There, crouched behind a little table, a young ginger-haired lad with a delicate and sickly countenance sat engrossed in his book-binding. There too they found the librarian, a tall, broad-shouldered man with a huge black beard who carried an air of absolute authority over both rooms. Amidst all of these stunted, sickly sons of the ghetto, he appeared as a colossus.37

Figure 1 The Free Russian Library. (Armfelt, ‘Russia in East London’, 1, 27).

The gentleman in question was Aleksei L’vovich Teplov, another of those revolutionary giants of the London emigration whom time has chosen to forget. It is remarkable, indeed, given the major role he played in the Russian East End, how rarely his name is to be found in histories of the period. As a young student in Russia in the 1870s, Teplov had become involved in spreading socialist propaganda amongst the railway workers of Penza province until his arrest and exile to Siberia. Fleeing to the west in the late 1880s, he had played an active role in the terrorist wing of the movement and had been one of those implicated in the 1890 Paris Bomb Plot. In February of that year in a forest on the outskirts of Paris, the unfortunate revolutionary received a serious wound to the thigh caused by the premature explosion of one of the experimental bombs he had been testing. And his misfortunes did not end there for, a few months into his convalescence, in the early hours of the morning of 29 May, he was one of those rudely awoken by the French police and taken into custody on charges of illegal possession of explosives. On his release from prison in 1893 and with the help of his old comrade Vladimir Burtsev, he crossed the Channel and settled in London. Here it was that, having apparently abandoned his flirtation with terrorism, Teplov decided to renew his work in raising the political consciousness of the masses: this time among the East European Jewish immigrant workers in Whitechapel. It proved to be a long and difficult task but eventually, some five years after his arrival, on 13 July 1898, he was able to announce the opening of his Free Russian Library and Reading Room at 15 Whitechapel Road, Stepney (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Russian Free Library. Library stamp. TNA HO 144/272/A59222B/21.

The foundation of the library had been achieved thanks in the main to the moral and financial support of Teplov’s fellow revolutionaries in exile such as Burtsev, Chaikovsky and V. G. Chertkov, Tolstoy’s literary agent and disciple newly arrived in Britain. But finding continued funding from a community which was itself impoverished was always going to prove problematic. Teplov turned, therefore, to his homeland with an appeal in which he explained that his intention was to give his impoverished fellow workers in the East End ‘the opportunity to maintain a spiritual relationship with their mother country and to retain contact with its literature and life’. His appeal, evidently, met with some limited success for, by the turn of the century, he had managed to relocate his business a few hundred yards along the road to the house at 16 Whitechapel Lane.38

Soon thereafter, having received additional support from certain local benevolent societies and individuals, the library developed into the cultural hub of the Russian East End. Apart from engaging in purely library matters, the staff arranged cultural excursions for the local community to museums, zoos and botanical gardens and organized entertainments of an educational nature for children. The Free Library also acted as an employment agency, advertising the services of experienced foreign language teachers and generalists, competent translators from and into all European languages, good copyists, guides, and so on. Indeed, the point had now been reached when Teplov had almost adopted the mantle of Alexander Herzen – a visit to whom had been considered obligatory for any Russian passing through London. Now, as the new century approached, the Free Russian Library in Whitechapel had gained such fame that it had become one of the top attractions for Russian visitors to the capital, especially if they happened to be of a radical bent. As a result, it also attracted the attention not only of certain other individuals, mainly in the employ of the Okhrana, but also of the CID and the French Sûreté.

A hotbed of revolution

The archives of the Sûreté Générale in Paris contain a series of fascinating reports compiled by one of their London agents in early 1902, in which he described the ‘Whitechapel Group’ as being one of the main Russian political émigré associations in England,39 and in which he claimed that the Free Library was the ‘rallying centre of the Russian revolutionary movement in London’. Moreover, Teplov, the manager of the library, was deemed to be ‘one of the most influential members of the revolutionary party here’.40

The un-named police agent also submitted copious newspaper extracts and a variety of notices and handbills advertising a range of entertainments offered by and on behalf of the library. But he went on to provide much more alarming news when he described how Teplov was offering courses in practical chemistry and giving instruction in complex substances and in formulas for nitro-glycerine. Furthermore, he reported on the group’s plans to organize Sunday trips to the countryside and, in passing, offered his own opinion that such excursions might give ‘to those revolutionaries following a higher calling, the opportunity to perfect their skills in the manipulation of chemical compounds by carrying out open-air experiments’.41 According to this agent, then, Teplov, the notorious Paris bomber, was in fact still practising his black art under the guise of mild-mannered librarian. However, there is no evidence in any of the archives I have examined thus far which would substantiate such an allegation.

And of course, it was not only the Sûreté who took an interest in the activities of the Free Library. The principal tsarist agent in the capital at this time was a French citizen by the name of Jean Edgar Farce (whose exploits and contacts with Lenin and his Social Democrats will be described in detail later). His meticulous reports to his superiors in the Foreign Agency in Paris covered the activities of all the revolutionaries in London and in much more detail than his counterpart in the Sûreté.42 This was thanks primarily to the close working relationship he had established with officers in Special Branch. In a later report he described how, thanks to his ability to read and understand Yiddish, he was able to pass on information from the local newspapers to Scotland Yard officers who in turn passed on information that would otherwise have been impossible for him to obtain. The agent’s detailed submissions on Teplov, in particular, were helped by the fact that, as he proudly boasted, one of his informants was ‘a regular reader at the Russian Library’.43 This would have come as no surprise to the émigrés who were well aware of spies in their midst. One young Social Democrat worker who was a regular attendee at the lectures arranged by the library recalled how ‘Russian spies swarmed around the platform and how Teplov would ignominiously grab them by the collar and throw them out.’44 Teplov himself was later interviewed by the London Daily News for a long item describing the arrival in London of ‘a special staff of Russian Police spies’. He had shrugged it off saying: ‘“We are used to spies by this time. A few extra cannot make a difference to us.” And he laughed merrily as he recalled some of his own experiences with the detectives.’45

It had been a matter of great regret to Teplov that one of the main champions of his library had not been present to see it open to the public. His absence, however, had been unavoidable for, by that point, in the summer of 1898, Vladimir Burtsev had already spent some six months languishing in a British prison. The quite remarkable story of how he ended up there, as the first Russian revolutionary to be thus incarcerated, is one which should feature prominently in any history of Russian London.

Rachkovsky’s new agent in London, Lev Beitner, had been in post for over a year when, on Christmas Eve 1895, the émigré community suffered a devastating loss with the tragic and inexplicable death of Sergei Stepniak when he was knocked down by a train at a level crossing in north west London. Although from eye-witness accounts it was clear that this was a tragic accident, pure and simple, it did not prevent the appearance of a scurrilous news story claiming that the writer had somehow been lured to his death by a mysterious English woman in the pay of the Russian secret police.46 Although this was unquestionably a ‘tale of cock and bull’ as the journal Free Russia described it, the removal from the scene of one of the most formidable opponents of the tsarist regime would doubtless have been welcomed by Rachkovsky and his London agents who could now redirect their energies towards other targets among whom Burtsev loomed largest.47

Since his escape from Siberian exile in July 1888, Burtsev had been near the top (if not at the very top) of the Foreign Agency’s most-wanted list but, despite Rachkovsky’s best efforts, the young revolutionary had always succeeded in slipping through his fingers. Having once more survived a police pursuit – this time through the Balkans, as described earlier – Burtsev settled in London where he was mostly to be found, as was the Russian custom, in the British Museum under the dome of his beloved Reading Room. Indeed, one of the first products of his labours was an excellent thirty-page article entitled simply, ‘The British Museum’ which appeared under the pseudonym N. Viktorov, in the respected Russian journal The Historical Messenger.48 This was the first full description of the Library’s holdings by a Russian and was written, quite clearly, as a guide to the collections for the ever-increasing numbers of his fellow revolutionaries who were now washing up on the shores of the Thames (prior to their arrival Lenin and his comrades would almost certainly have been among those who had familiarized themselves with this informative article). Burtsev’s main academic preoccupation during this period, however, was a collaborative project with Stepniak involving the compilation of materials for a history of political and social movements in nineteenth-century Russia. (Unfortunately, the latter had passed before the volume eventually saw the light of day in 1897, under the title A Century of Political Life in Russia (1800–1896).49) Lenin himself is known to have made heavy use of this ‘essential work of reference for every Russian radical’ in one of his later articles.50 And the book was not only popular amongst revolutionaries – no less a figure than S. E. Zvoliansky, the new director of the Department of Police, showed he was a believer in the old maxim ‘know your enemy’ by asking for ten copies to be sent to him and, two months later, placing an order for ten more.51

Burtsev then turned his full attention to a project long in gestation – namely, the publication of a new radical journal Narodovolets (Member of the Party of the People’s Will) which called for the resumption of revolutionary activities, including terrorist acts, within Russia, and roundly censured Lenin’s nascent Social Democrats for their lack of support which, the editor believed, was responsible for the current lull in such activities. The first issue appeared in April 1897 and created quite a storm, not only among his political opponents but also among some of the leading émigrés in London who, in the atmosphere of tension and anxiety which still gripped Europe following the anarchist outrages of recent years, were highly unlikely to be persuaded openly to declare support for terrorist acts, whether confined to Russian soil or not. Meanwhile, in St Petersburg, Director of Police Zvoliansky was instructed to draw up a detailed plan that would ensure the troublesome editor could be brought to justice once and for all.52 Rachkovsky was assigned to the task and immediately called on the assistance of his old acquaintance Melville at Scotland Yard. Rachkovsky and his masters followed the chief inspector’s counsel to the letter which resulted, on 16 December 1897, in Burtsev’s dramatic arrest in the vestibule of the Reading Room of the British Museum itself. The charge, engineered jointly by Melville and the Russian Police, was that of ‘unlawfully encouraging certain persons whose names were unknown, to murder his Imperial Majesty Nicholas II, Emperor of the Russias’.53

With liberal London exploding in protest at this self-evident set-up, concocted at the behest of the Russian tsar, the British authorities rushed to complete proceedings and, two months later, Burtsev was brought to trial at the Old Bailey where he was found guilty as charged. The judge handed down the maximum penalty permissible by law of eighteen months solitary confinement with hard labour. Again, despite numerous pleas for clemency from the émigré community and their British supporters, Burtsev would be obliged to serve his sentence, in full, in Pentonville Prison and later in Wormwood Scrubs.

The revolutionary’s autobiography contains a powerful reminiscence of his time in detention and the appalling conditions he endured.54 It was the opinion of this man, already familiar with the rigours of prison life in Russia, that the British regime was by far the harsher of the two, and incomparably more severe than the French system: unlike the Maison de la Santé prison in Paris where prisoners could smoke, take walks together and were even allowed spirit stoves in their cells, life in Pentonville was quite another story with its solitary confinement, hard-labour, the indignities of the slopping-out bucket, the bed of bare boards and the constant threat of further punishment.55 As a direct result of such appalling conditions Burtsev’s health collapsed and, on his eventual release in July 1899, he was found to have contracted tuberculosis. Advised to seek an immediate rest cure on the coast where he could breathe in the salty sea air, his friends dispatched him to Christchurch on the south coast to where Vladimir Chertkov had recently relocated his Tolstoyan colony. There, from early morning to late at night, the invalid was to be found sitting by the seashore, wrapped in a shaggy plaid blanket. However, unable to rest, he was soon back in London, engaged once more in his studies at the Museum. His labours, however, were soon interrupted when he again fell seriously ill and was obliged to leave London for a prolonged rehabilitation in the Swiss mountains.56

This effectively brought an end to Burtsev’s lengthy residence in Britain, a stay which had witnessed quite a remarkable societal change in the country. Whereas in 1891, the revolutionary had experienced the warmth of that welcome which Britain had traditionally extended to political refugees; as the decade progressed, he witnessed a distinct rise in British anti-alienism – first, solely on social and economic grounds but then hijacked for political ends. By the time of his arrest, public opinion had already swung violently against immigration, while the long-cherished British policy of political asylum itself was coming under attack. This change in attitude towards aliens in general resulted, a few years later, in calls for their total exclusion from Britain which was, to all intents and purposes, the effect achieved by the Aliens Act of 1905, despite claims that political refugees were explicitly excluded from its remit. Those few who opposed the introduction of the Act rightly saw in it ‘a measure, calculated to stir up anti-foreign feeling and race prejudice, a reactionary measure that would bear very harshly on the victims of political or religious persecution’.57 But such warnings fell on deaf ears. The Act was duly passed and came into force on 1 January 1906. In 1891 Burtsev had, with some relief, arrived in Britain, the only remaining place of political asylum in Europe. By the time he returned to Russia in 1905, he and his associates had already witnessed the sad demise of that last refuge.58

This, then, was the direction in which Britain was already heading when a new wave of Russian Social Democratic revolutionaries led by Lenin arrived in London in the early years of the century. And it is possible that it was this change in societal attitude which caused the Bolshevik leader such problems on his arrival – such as the difficulties he encountered in gaining entry to the Reading Room of the British Museum: out of the ninety or so applications I have come across from revolutionaries of all descriptions, the Museum authorities demanded a second reference only twice, and on both of these occasions it happened to be Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov-Lenin who was applying for admission.

The Richters arrive

Considering he had only recently completed a term of exile in Siberia, the young Lenin had encountered surprisingly little resistance from the authorities when, in May 1900, he applied for a visa to leave Russia (on the pretext of seeking medical treatment for his ulcer problems and of continuing his studies). Two months later, having said farewell to his family and bidden au revoir to his wife who, like him, had also been exiled but who was still serving out her term, he crossed the Russian border on his way to Switzerland to visit Plekhanov and others in the ‘Emancipation of Labour Group’ to discuss plans for a Marxist newspaper, which he had drawn up while still in Siberia. In September he moved to Munich where he established his centre of operations and in late December 1900 saw his plans come to fruition at last with the appearance of the first issue of his newspaper Iskra (The Spark) – a title, incidentally, which pointed to Lenin’s great admiration for the participants in the revolt of December 1825. The newspaper’s motto, ‘From a spark a flame will flare up!’, was taken from the poem ‘The Decembrists’ Answer’ written by one of those who took part in the uprising, the exiled poet Alexander Odoevsky in response to Pushkin’s impassioned poem of support for their revolutionary cause, ‘Deep in Siberia’s Mines’.

On completion of her sentence in April 1901, Krupskaya too was allowed to leave Russia and headed for Munich to be reunited with her husband. Over the next year or so, with her help, Lenin and his co-editors (Georgy Plekhanov, Vera Zasulich, Yuly Martov, Aleksandr Potresov and Pavel Axelrod) succeeded in producing a total of twenty-one issues of the newspaper, first on a monthly and then on a bi-monthly basis, with an average print-run of 8,000, and occasionally topping 10,000, until pressure from the German police obliged them to move operations. The group was divided on where they should select for their next base with Plekhanov and Axelrod expressing an obvious preference for Switzerland. Lenin, however, had already opted for London.

The reasons behind this choice are unclear. Lenin had never visited England before and had little proficiency in the language. At that time, London was the virtual home of his ‘economist’ enemies and there were very few ‘orthodox’ Russian Social Democrat voices to be found there. Moreover, he had no English Marxist contacts whatsoever. Perhaps he wished to make use of the riches of the British Museum Library, or simply wanted to escape the attentions of the Okhrana and take advantage of that hospitality towards political refugees for which Britain was famed. Alternatively, he may have had another reason entirely. For it is quite possible that he was keen to renew an ‘old friendship’ with a certain dear comrade whom he had not seen since his release from prison in St Petersburg in February 1897 and who, he knew, was now resident in London. Was there perhaps in London another spark which Lenin hoped could be rekindled into a flame? However that may be, and for whatever reason (or reasons), as was now becoming usual, Vladimir Ilyich got his way – London it would be.

And so it was that around the middle of April 1902 he and Krupskaya, his dutiful wife, disembarked from a cross-channel ferry at Dover and set foot on British soil for the first time. The minutely detailed official Soviet chronicle of Lenin’s life, which runs to thirteen substantial volumes, can only narrow their date of arrival down to between Sunday 13 and Thursday 17 April (although another source claims it was Monday 14 April).59 Similar uncertainty surrounds their exact point of arrival in London. Some say Victoria station, others Charing Cross. Unfortunately, British police records are of no help here, which is surprising given the numerous instances of contemporaneous, meticulously detailed police reports on the cross-channel arrival and onward travel of other Russian radicals of much lesser import than Lenin.

One such example from the archives of ‘the Met’ concerns the arrival from France in October 1900 of the Russian anarchist Ivan (John) Lebedinsky.60 The police file begins with a report from that same PC Francis Powell, whom we encountered earlier in the British Museum but who, having reached the rank of sergeant, was now stationed in Dieppe. His report described Lebedinsky arriving on the evening boat train from Paris and boarding the SS Sussex bound for New Haven. Powell pointed Lebedinsky out to the purser and gave him a note to pass on to the officer in charge at New Haven. When the ferry arrived, the officer interviewed the Russian who told him he was going to take up a job in a newspaper with the Tolstoyan Vladimir Chertkov who was, at that time, still living at an address in Croydon. A telegram was sent to New Scotland Yard alerting them to Lebedinsky’s departure on the Victoria portion of the morning boat train. On arrival in London he was met by two PCs who tracked him first to a café on Oxford Street where he had breakfast, thereafter to London Bridge Station and thence to Forest Hill and to the home of the Russian revolutionary Hesper Serebriakoff at 53 Siddon Road.61

Given that such meticulous tracking of suspect aliens by the Yard was by no means uncommon, the question arises of how Lenin, head of a vast network of Russian political activists, managed to avoid detection so easily. Opinions vary. Some put it down to his mastery of ‘konspiratsiia’, which to the Russian has a specific meaning of ‘underground secrecy’ or ‘secrecy or stealth in avoiding detection’.62 Others claim that at this early stage of his career, Lenin’s role as de facto leader of the Russian Social Democrats was not widely known. Yet others take his unusual ability to move freely around Europe as further evidence of his cosy relationship with the Russian police – an intriguing accusation which we shall examine in due course.

But, whichever the railway terminus was, we do at least know that there to meet the couple was Nikolai Aleksandrovich Alekseev, a political acquaintance from their St Petersburg days who, like them, had been arrested for his activism but who, unlike Lenin and most of his other comrades, found Siberian exile impossible to bear and therefore made his escape in 1899, arriving the following January in England.63 He settled in a flat in north London near King’s Cross Station at no. 49 Sidmouth Street which he described as ‘one of the slum streets of London’. However, the location evidently suited him since, in the census of the following year, ‘journalist/author Nicholas Aleksieev’ was listed as one of four lodgers of Mr and Mrs Freemantle who lived next door at no. 47.64 Sidmouth Street ran along the south side of Regent Square, an area which had been associated with East European radicals since at least the early 1850s when no. 38 on the north side served as home to the Polish Democratic Press and also temporarily housed Alexander Herzen’s Free Russian Press when it first started production in 1853.65 There are also documents dating from 1885 linking Sergei Stepniak to no. 45 on the east side, although whether he lived there or merely used the house as a correspondence address is unknown.66 Despite its location in the very centre of the capital and its proximity to one of London’s busiest railway terminals, Regent Square, with its two churches and twelve majestic London plane trees, had about it (and still has) an air of tranquillity, and it was doubtless the peaceful atmosphere of the area (and the fact that it was a mere ten-minute walk away from the British Museum and its famed library) that served as an attraction to Herzen and Stepniak in their time just as it did to Alekseev in his. And it was to this seemingly ideal spot that the latter now conducted his two newly arrived charges. However, the address in question was known; not only known to a small handful of East European revolutionaries, but had, in fact, come to the attention of the British public some ten years earlier and, as a result, still retained a reputation of some notoriety. As some of the older residents could have testified, serenity had not always reigned in Regent Square.

Tragedy in the Square

In the early hours of Thursday 21 September 1893, the tranquillity of Regent Square had been shattered as four pistol shots rang out. Later that morning the national newspapers carried the shocking tale of a dreadful crime of passion which had cost three young lives. The press pack then moved on from the square to the Coroner’s Court from where there emerged details of the horrific murders of Bessie Montague, a 23-year-old chorus singer at a West End theatre who lived at no. 18 Regent Square, and her male companion, Samuel Garcia, a 26-year-old stockbroker, and also of the suicide of Leo Percy, a 26-year-old electrician who had been engaged to marry Miss Montague until the latter terminated the arrangement three years earlier. On the night in question, the jilted lover had lain in wait in the Square and had accosted Miss Montague and her companion on their return. Percy produced a pistol and, as his former fiancée tried to flee, shot her in the back. He fired his next bullet at Garcia as he too tried to escape but it missed and went through his hat. The third, however, hit the unfortunate Garcia in the back of the head. Percy had then, evidently, placed the pistol in his own mouth and, with his fourth shot, had committed suicide. A letter he had written to his father some ten days before the tragic events occurred was later found on his body. It read as follows:

My dear Father – I have no doubt that by the time you receive this you will know all, if what I expect occurs. I can bear it no longer. The pain and humiliation is too great, so it is best ended. I determined long ago that no other one should have her. I am sorry if I give you pain but there is nothing I can live for now. My best love to all. – Your affectionate son, Leo.67

This tale of tragic, unrequited love had unfolded almost ten years before Lenin’s arrival and there is no reason to suppose that he would have been informed of the Square’s dark history. Had he known, however, it is possible he may have paused to reflect on the irony of the situation given the identity of two of the inhabitants who lived nearby.

There are conflicting accounts of what happened following Lenin’s arrival in the Square. It is known that he and Krupskaya lived for just over a week near to Alekseev’s lodgings in a ‘dormitory room’ rented out by the poor owners of the flat, but it is unclear who had made these arrangements on their behalf. Many historians have relied heavily on Alekseev’s reminiscence, in which account he himself claims responsibility not only for finding accommodation for the new arrivals but also for helping Lenin set up his newspaper and even for arranging his admission to the British Museum. (The German Socialist Max Beer was another of those who would later claim responsibility for helping Lenin arrange the printing of Iskra in London.68) However, there is another version, confirmed in part by Krupskaya herself, in which it is pointed out that, in reality, most of the assistance offered to the new arrivals was supplied by an enigmatic young Russian émigré couple who, on their arrival in London a few years earlier, had adopted the pseudonyms of Robert and Paulina Tar. They had moved into Regent Square the year before Lenin’s arrival and had taken up residence at no. 20, just two doors away from the scene of the horrendous murders and suicide described above.

Although both Robert and his young schoolteacher wife have received occasional mentions in histories of the period, the full extent of the help they offered Lenin and Krupskaya, both as welcoming party and as much more besides, has been either overlooked, ignored or more likely, as I will argue below, deliberately obscured and suppressed.69 To date, the history of the complex, and at times stormy, relationship which existed between the two couples has hardly received a mention and it is certainly worthy of examination here for the new light it throws on an under-reported period of Lenin’s life and on an intriguing aspect of his psychological make-up. However, to fully understand the nature of this relationship it is necessary, first, to travel back some ten years to the Russian capital, St Petersburg.