As has been well documented elsewhere, Lenin’s final years in European exile, following his departure from London in late 1911, were far from easy.1 He and Krupskaya restlessly flitted from city to city – first Paris, then Prague and then, in the summer of 1912, Krakow. All the while, the Bolshevik leader was constantly on the lookout for tsarist police agents – under Krasil’nikov’s guidance, the Foreign Agency was once more becoming a force to be reckoned with and posed a threat to Russian émigrés wherever they might be – not only on the continent but also in Britain, where relations with Chief Superintendent Quinn of the Yard had survived the embarrassing departure of Garting and were now flourishing, and where Krasil’nikov’s London outpost was witnessing a revival under the stewardship of none other than Francis Powell – ‘Inspector First Class of the Political Detective Department of Scotland Yard’ – who had been newly recruited on Quinn’s recommendation.2 Indeed, had Lenin remained in London, it is unlikely he would have been able so easily to maintain his previous cloak of invisibility.

In Krakow, meanwhile, police surveillance was only one of the problems with which Lenin had to contend. The health of his wife had suddenly deteriorated and they were obliged to seek out the help of a local expert neurologist who diagnosed thyroid trouble and attempted to treat her symptoms with electro-convulsive therapy and bromides. Perhaps not surprisingly, the treatment had little beneficial effect and, with the arrival of spring, the consultant suggested she take a rest cure in the mountains. The couple moved then to Zakopane in the Tatra Mountains where the unfortunate Nadya was subjected to a three-week ‘electricity cure’, but again without success. As Lenin reported: ‘Results – nil. Nothing has changed – the same bulging eyes, swollen neck and palpitations of the heart – all the symptoms of goitre.’3 Eventually, with her condition worsening, it was decided that an operation would be necessary and so they moved to Berne where, in July 1913, Nadya underwent a thyroidectomy. Thankfully, the operation proved successful and, thereafter, she slowly began to recover.4

But at that time, Lenin had other concerns, quite apart from the poor health of his wife. In May the previous year, he had learned of the arrest in Saratov of his sisters Mariya and Anna when, following a police raid, they were found to be in possession of forbidden publications.5 Although Anna was later released, Mariya did not have the same good fortune, receiving a sentence of exile to Siberia. On 1 December 1912, accompanied by her brother-in-law, Mark Elizarov, she set off for Vologda which was to be her place of banishment for the next two years.6 And it is at this point, almost coincidentally, that Lenin’s alleged first love, Apollinariya Aleksandrovna Yakubova-Takhtareva re-enters our story.

A month earlier, a mutual acquaintance – possibly Lidya Knipovich – had informed Apollinariya of Mariya’s exile to her own home province of Vologda and she had immediately contacted her aunt, Elizaveta Irineevna. The latter was still living in Vologda but had long since given up revolutionary activity and was now married and bringing up a family. Apollinariya was sure that Aunt Liliya would bravely and without question offer up what support she could to ease the difficulties of the unfortunate exile. And this, of course, is what she did.7

But what had happened to Apollinariya and her husband Konstantin Mikhailovich since agent Farce had last reported on their activities in London at the time of the RSDLP’s 1905 Congress? As described in an earlier chapter, towards the end of that year, following the publication of the tsar’s October Manifesto and his subsequent declaration of an amnesty for political refugees, many in the Russian East End and in other centres of the emigration in Europe decided to make an immediate return to their homeland. However, two émigrés who did not immediately rush back to Russia at that time were the Takhtarevs. Instead, they stayed on in London until March of the following year.8 Thereafter, their history becomes somewhat sketchy but, given the important and hitherto under-reported role played by both in the history of the Russian emigration and, indeed, in Lenin’s early years, it is perhaps only fitting that we end our story with the conclusion of theirs.

The St Petersburg Takhtarevs

Although a certain amount is known about Konstantin Mikhailovich’s later life, the fate of his wife is much more of a mystery. Be it by decree of Lenin, or Krupskaya, or for some other entirely different reason, this co-founder of the famous League of Struggle for the Emancipation of The Working Class had been almost written out of history. For example, in a Soviet collection of reminiscences of Krupskaya, in the sections covering her early years in St Petersburg and London, there is not a single mention to be found of Apollinariya Yakubova-Takhtareva, despite the closeness of the two women throughout that period.9 Indeed, scholars have been unable to agree even on the year of her death – some saying 1913, others, 1917. It is only now, with the appearance of Yakubova’s personal papers, that the date of her passing can finally be confirmed as May 1914. These papers also enable us to fill in some of the other gaps in her heroic and ultimately tragic life.

In the spring of 1906, the Takhtarevs bade farewell to London and to their conspiratorial personae, Robert and Paulina Tar, and crossed the Channel bound for St Petersburg. Neither their exact date of arrival nor their first address in the Russian capital is documented, but it is known that within two years they had established themselves, together with other members of Konstantin’s family, in the district of Lesnoi in an imposing two-storied detached house which Konstantin’s father, General Mikhail Konstantinovich Takhtarev, had only recently finished building. The house, at no. 18 Institutsky Prospect, still stands (and, incidentally, is still known as the Takhtarev house10).

Shortly after her return to Russia, Apollinariya had set off for her home village of Verkhovazh’e in Vologda province for a long overdue reunion with her parents and other members of her family. From one of her letters to her husband who had stayed behind in St Petersburg, it is clear that, after the buzz and clamour of her six years in London, she found it difficult initially to adapt to what she referred to as the ‘impenetrable backwardness’ and philistinism of provincial life.11 The countryside was just as beautiful as she remembered it but the people she encountered seemed to be disconnected from the real world. She recounted how on her journey there she had entered into conversation with her coach-driver and asked his opinion on the new State Duma which had met for the first time earlier that year. She reported that, as far as the coach-driver was concerned, things would be fine if they could just get rid of the village superintendents and the obstetricians! Apollinariya was unsure what he meant by this but, in fact, she would soon discover that even amongst the village bourgeoisie, there was no one with whom she could have a more meaningful conversation. She, therefore, spent most of her time either jam-making or swimming in the nearby river Vaga, where she was often joined by her brother’s children and their friends. In her letter she described these youngsters in terms of real warmth and joy and it may well have been that, in expressing these sentiments, she was betraying signs of a maternal instinct and a desire to have children of her own.

And so it was that within a year or so, Apollinariya herself fell pregnant and gave birth to a son, whom they named Misha after his paternal grandfather. But, sadly, the joys of motherhood were interrupted after only a short while when she fell ill, complaining of headaches, high temperatures and a persistent cough. As her condition worsened, she was obliged to abandon her husband and baby and seek out a sanatorium in the Karelian Isthmus to the north of St Petersburg in an attempt to find a cure for her deeply worrying condition. She arrived at the sanatorium in the small town of Mustamyaki (now Yakovlevo) in February 1909 and, after a few weeks, wrote to her husband, optimistically reporting, that, thanks to the compresses and other medical treatment received, her symptoms appeared to be less severe. The doctor was of the opinion that her condition might even be improving slightly, but warned that a complete cure would require a full four-month course of treatment. The patient, of course, considered this to be quite out of the question. She could not bear to be separated from her husband and child for so long.

Apollinariya’s earlier split with Krupskaya and Lenin had not dampened in any way her friendship with his sisters and mother and their other mutual acquaintances. Vladimir Ilyich’s sister Mariya wrote to her older sister Anna at that time, passing on less optimistic news of their friend’s condition and reporting that the doctors had found a mass of tubercular bacilli in her sputum and did not think there was much hope of recovery – at that time tuberculosis was still an incurable disease. Their friend Lidya Knipovich who lived nearby, reported that Apollinariya had written to her old flatmate Zina Nevzorova saying that although her temperature was normal, she had lost some weight and, most annoying of all, she was thoroughly bored with sanatorium life.12 Given the regularity of the correspondence which flowed between Lenin, his sisters, mother and also with their close friends such as Knipovich and Nevzorova, it is almost impossible to conceive that Lenin and Krupskaya had not been informed of the poor health of their former close friend but, unfortunately, no documentary evidence to that effect exists.

Meanwhile, back in St Petersburg, Apollinariya’s husband had already taken up a post as lecturer at the newly founded Psycho-Neurological Institute. His work obliged him to make extended trips to London to conduct research in the British Museum Library and, with his time thus accounted for, was finding it quite impossible to look after young Misha on his own. The couple were, therefore, obliged to accept the kind offer of child-rearing services proffered by Konstantin’s mother Elizaveta Klavdievna Takhtareva and her sister Sonya. Whether Apollinariya managed to hold out at the sanatorium for the recommended full four-month course of treatment, or whether she cut her stay short and rushed back to her family is unknown, but, by August that year, her health had worsened and she was once more obliged to move into a sanatorium, this time in Yalta in the Crimea. There exists a fragment of a touching letter she wrote in response to one she had received from her husband dating from that period, in which she refers to Konstantin as her magician who has managed to pull her out of her well of misery and whose dear sweet letters have restored her health and happiness. She ends with a deeply moving description of her love for him:

But for now, good night, my beloved. Tenderly, I rest my head on your chest and look into your eyes. Can you feel my happiness, the warmth of my love for you? I love your body and your soul, I love you just as you are – a good man. I love your work and your enthusiasm. I love your love for our baby. I love you for everything that has passed between us in our lives. And there were some bright moments there too, isn’t that so?!

… A moment ago I stepped outside and was captivated by the sight that greeted me. The clouds had dispersed and had left behind them a starry sky and a bright full moon which magically lit up the alleyway just like that time when the two of us took a stroll at harvest time. Do you remember? Oh, this is such an enchanting place. I came back into my room and let my hair down. I looked in the mirror and what a bright, happy face I saw looking back at me. I must say, I was actually quite surprised! But there you are. That is the kind of soothing effect your dear sweet letters have on me. You see, I simply cannot stop writing about how much I love you.13

But her love for her child was, if anything, even stronger, and proof of that affection, indeed joy, is captured in a charming photograph of mother and child taken around that time.14 During her long periods of convalescence she waited anxiously for updates on Misha’s health and progress and, on receiving news, would write of how happy she was to hear about his successes in his Russian language studies; about the games he played and about a visit he had made to the zoo and how, on seeing a real live bear, he had been able to recognize it and identify it as his memed – (child-speak for medved’: ‘bear’.) Incidentally, that same little teddy bear found its way into a family photograph where it can be seen perched on Apollinariya’s left shoulder.15

On another occasion, Apollinariya received a letter from her sister Lyuba reporting on a visit she had paid to the Takhtarevs and relating in detail everything she could about young Misha, whom she found to be a healthy, sweet and intelligent little boy. She described a favourite game that he played with his uncle Valentin, Konstantin’s younger brother. They called it ‘monoplanes’ and it involved Valentin taking Misha by the scruff of the neck – like a kitten – and whirling him around in the air so that he flew just like a toy monoplane on a string. (This, of course, was at a time when powered flight was still in its infancy – it was only in July 1909 that Blériot had become the first to fly the English Channel – and aeroplanes were still capturing the imagination not only of children, but also of adults like Lenin himself who, residing at that time in Paris, had developed a passion for watching air-displays.16) One wonders whether it may have been her son’s fascination with aeroplanes that inspired Apollinariya to write her illustrated children’s book How People Fly.17 Such news of the happy life that Misha was leading was bound to gladden his mother’s heart but, doubtless, she would have been saddened by the news that her beloved son had started to call his grandmother, Elizaveta Klavdievna, ‘Mamochka’ – earlier she had been known as ‘Mamasha’ – and that now, in order to differentiate between the two, he had started to refer to Apollinariya simply as ‘Mama Polya’.18

There were periods when Apollinariya appeared to be regaining her health, but her treatment was expensive, with rooms in the Crimean sanatoria costing upwards of fifty roubles, and she and her husband were beginning to experience severe financial hardship. In the summer of 1911, Lidya Knipovich wrote to Mariya Ulyanova with news that Apollinariya’s sister was planning to build a winter dacha for her to the north of St Petersburg in the town of Seivisto (now Ozerki) on the Gulf of Finland, near modern-day Zelenogorsk, and it appears that, thanks to a loan from her father, the dacha was successfully completed.19

Mariya Ilyinichna continued to keep in touch with her old friend Knipovich and to pass on what news she received to other members of the Ulyanov family but, as mentioned above, that correspondence was temporarily suspended with Mariya’s arrest in May 1912. Fortunately, contact would be re-established with her arrival in Vologda later that year and her introduction to Apollinariya’s aunt. It is a matter of some regret, however, that it would appear Apollinariya would never know how warmly she was remembered at this time by the Ulyanov sisters and their mother.20 In January 1913, Mariya wrote from Vologda to her family passing on the ominous news she had received:

Have you heard the sad news about Polly? It turns out she has been very ill, and the doctor has told her, or someone close to her, that she will not last until the summer. I am sure she will face it bravely! But how terribly sorry I feel for her …

And so, she will die – for nothing – for no reason. I saw a recent photograph of her and my, how she has changed. Most likely her illness has now progressed from chronic to acute … Her sister has arranged a doctor for her in Vologda province.

It is possible that the photograph referred to is the one in Apollinariya’s archive, dating from around 1912, in which it does appear her illness has begun to take its toll.21 But still she tenaciously held on and even appeared to rally. In May 1913, Lenin’s mother had joined her daughter in her Vologda exile and, throughout the year that followed, received updates from Apollinariya’s aunt on her progress. As late as 25 April (8 May) 1914, she was writing to her daughter Anna in St Petersburg about how pleased she was to hear that Polly was feeling better, that they were not going to take the invalid to Switzerland, as had been previously planned, and that she was going to hold her aunt Liliya to her promise to come and stay with her until July, depending, of course, on how she was feeling.

Unfortunately, none of these plans came to pass. In the end, the former ‘force of the black earth’ was unable to stop the inexorable progress of her illness, although she did, at least, succeed in postponing the inevitable. Apollinariya Aleksandrovna Yakubova-Takhtareva finally passed away some time around mid-May 1914. She was buried in Zelenogorsk to the north of St Petersburg. Nothing is known of her funeral arrangements and, unfortunately, the local church authorities hold no record of her interment.

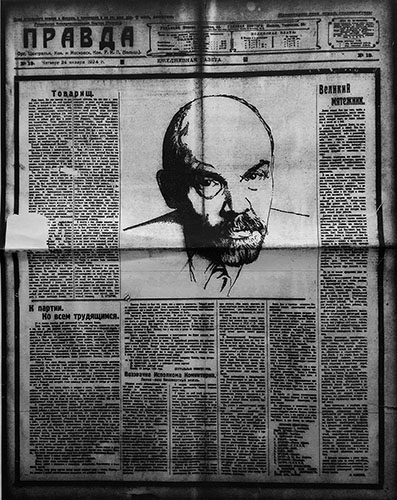

Her grieving husband stayed on with his family in the Takhtarev house in Lesnoi. At some stage, his son Misha moved out to the village of Lembolovo, to the north of Lesnoi, to live with the family of Apollinariya’s life-long friend Zinaida Nevzorova-Krzhizhanovsky. The family archive contains no verifiable information as to his fate, but it is thought that Misha perished in the battle of Moscow during the Great Patriotic War. Konstantin Mikhailovich remarried and his new wife, Mariya Semenovna, moved into the Takhtarev house where, in the early 1920s, she gave birth to a daughter, Nina. Takhtarev continued his career as an academic, practising and publishing in the field of sociology until 1924, the year of Lenin’s death (see Figure 10), when, returning from a study trip to London, he learned that his lectures at the University had been banned. He himself was fired from his post in September of that year, possibly as a direct result of some not entirely flattering personal memoirs of the late Soviet leader he had recently published. They, and he, had been immediately attacked by Lenin’s sister Anna and this in itself may have served as the reason for his dismissal.22 Sadly, Konstantin Mikhailovich would survive only until 19 July the following year, when he died suddenly of typhus.

Figure 10 Announcement of death of V. I. Lenin. (Pravda, 24 January 1924).

It is heartening, at least, to learn that Takhtarev’s collected sociological works have recently been reprinted and that his considerable achievements in that field are once more being recognized.23 As for his first wife, although forgotten by almost everyone, she was remembered fondly by her devoted husband, who dedicated several of his historical and sociological works to her memory. In one of his final publications, the fifth, 1924 edition of his Workers’ Movement in St Petersburg the dedication reads:

To the memory of A. A. Yakubova-Takhtareva, my selfless friend who magnanimously sacrificed her life for the cause of the emancipation of labour.24

Unlike Lenin, neither she nor her husband has ever been honoured with a monument to their memory, either in their homeland or in England, their adopted country of exile. It is safe to say, however, that Apollinariya would not have wished for any memorial other than the above.