The Cathars and Huguenots: The History and Legacy of the Major French Christian Groups Who Were Persecuted by the Catholics

By Charles River Editors

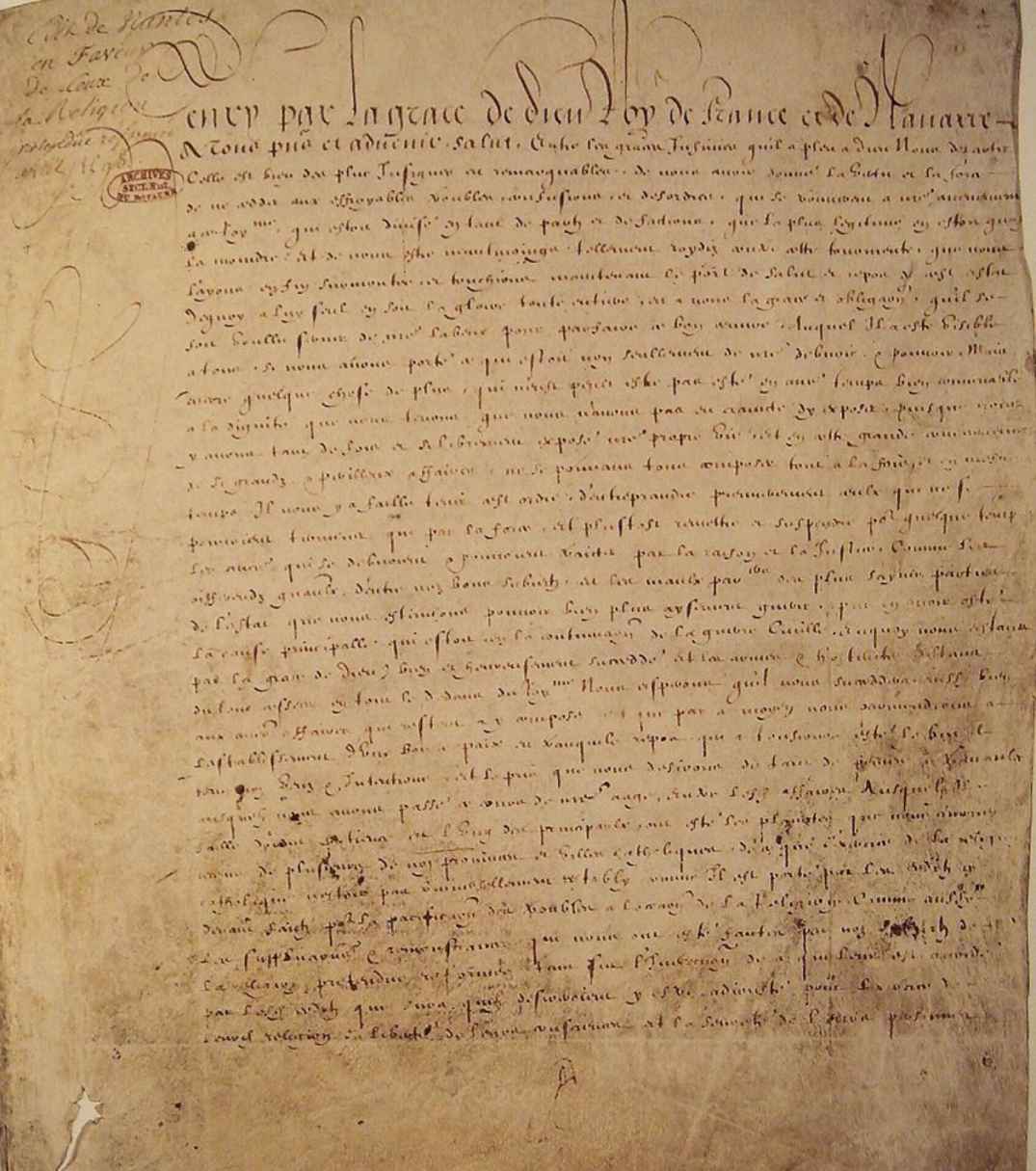

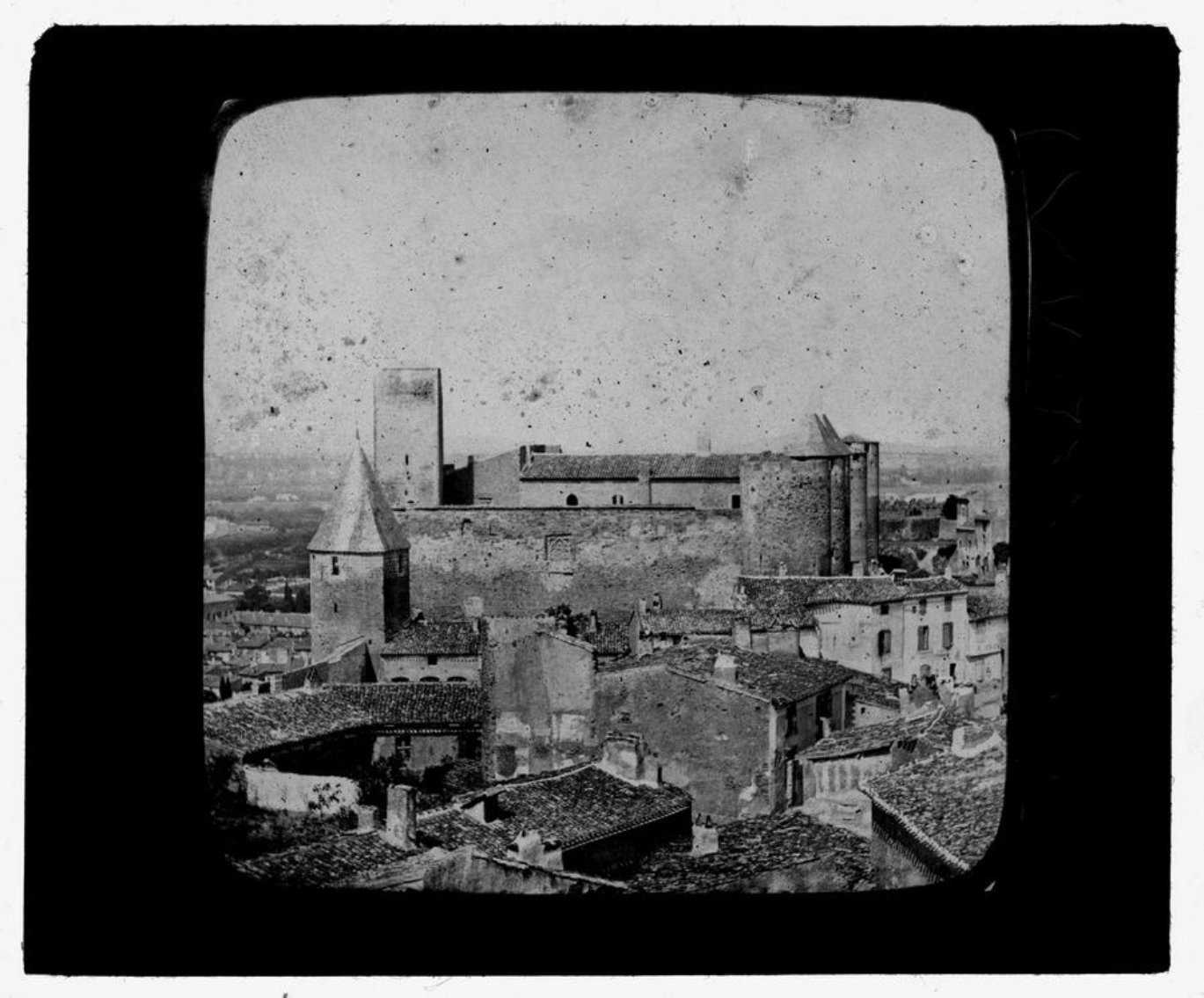

Chen Siyuan’s panorama of Carcassonne

About Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors is a boutique digital publishing company, specializing in bringing history back to life with educational and engaging books on a wide range of topics. Keep up to date with our new and free offerings with this 5 second sign up on our weekly mailing list, and visit Our Kindle Author Page to see other recently published Kindle titles.

We make these books for you and always want to know our readers’ opinions, so we encourage you to leave reviews and look forward to publishing new and exciting titles each week.

Introduction

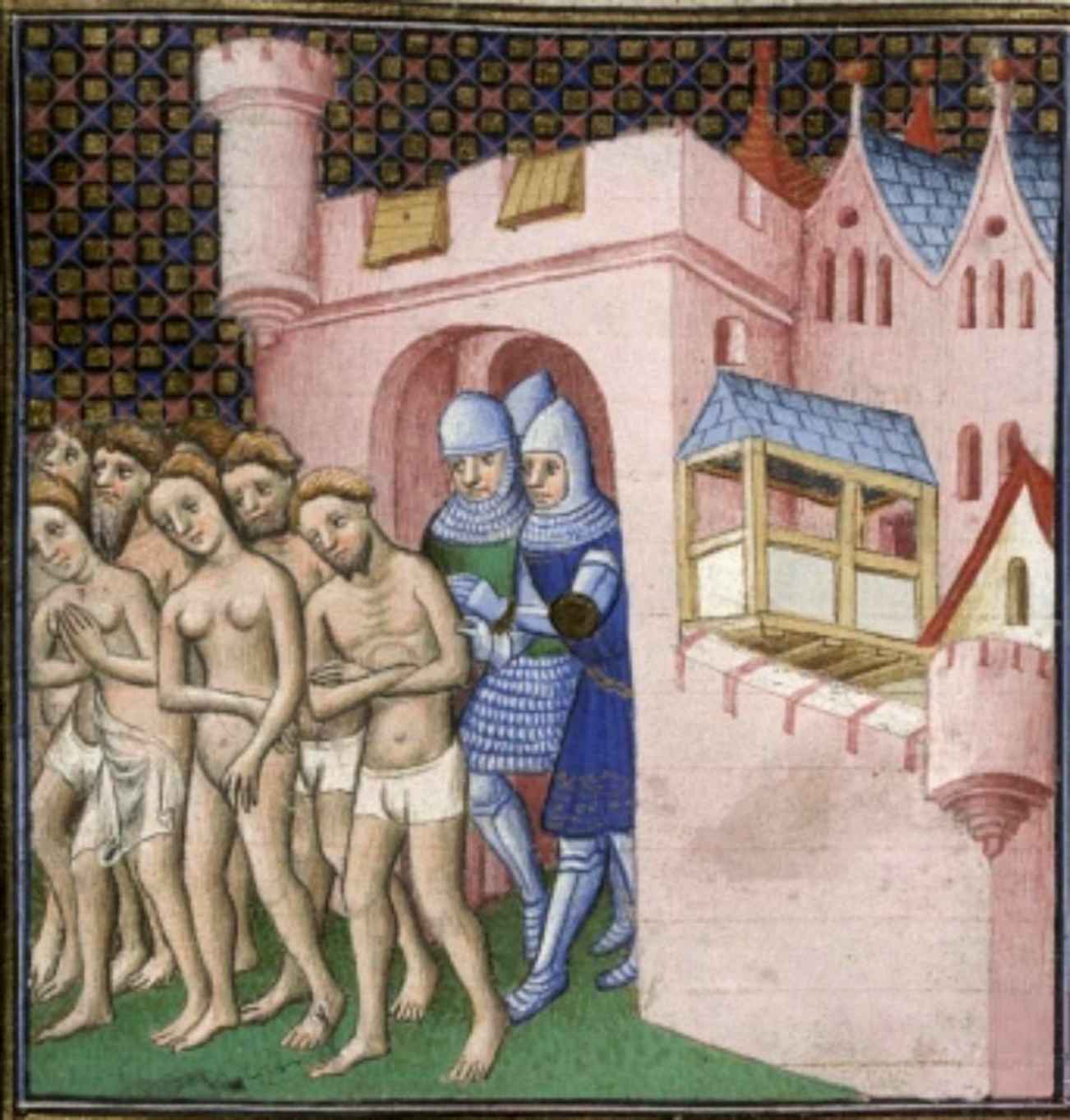

A medieval depiction of Cathars being expelled from Carcassonne in 1209

“The Roman Church...[says] that the heretics they persecute are the church of wolves. But this is absurd, for the wolves have always pursued and killed the sheep, and today it would have to be the other way around for the sheep to be so mad as to bite, pursue, and kill the wolves, and for the wolves to be so patient as to let the sheep devour them!” – Excerpt from the alleged writings of the Cathars

“A dog barks if he sees someone attacking his master; I would indeed be cowardly if, seeing the truth of God thus attacked, I played the mute, without saying a word.” – John Calvin to Marguerite, Queen of Navarre, April 1545

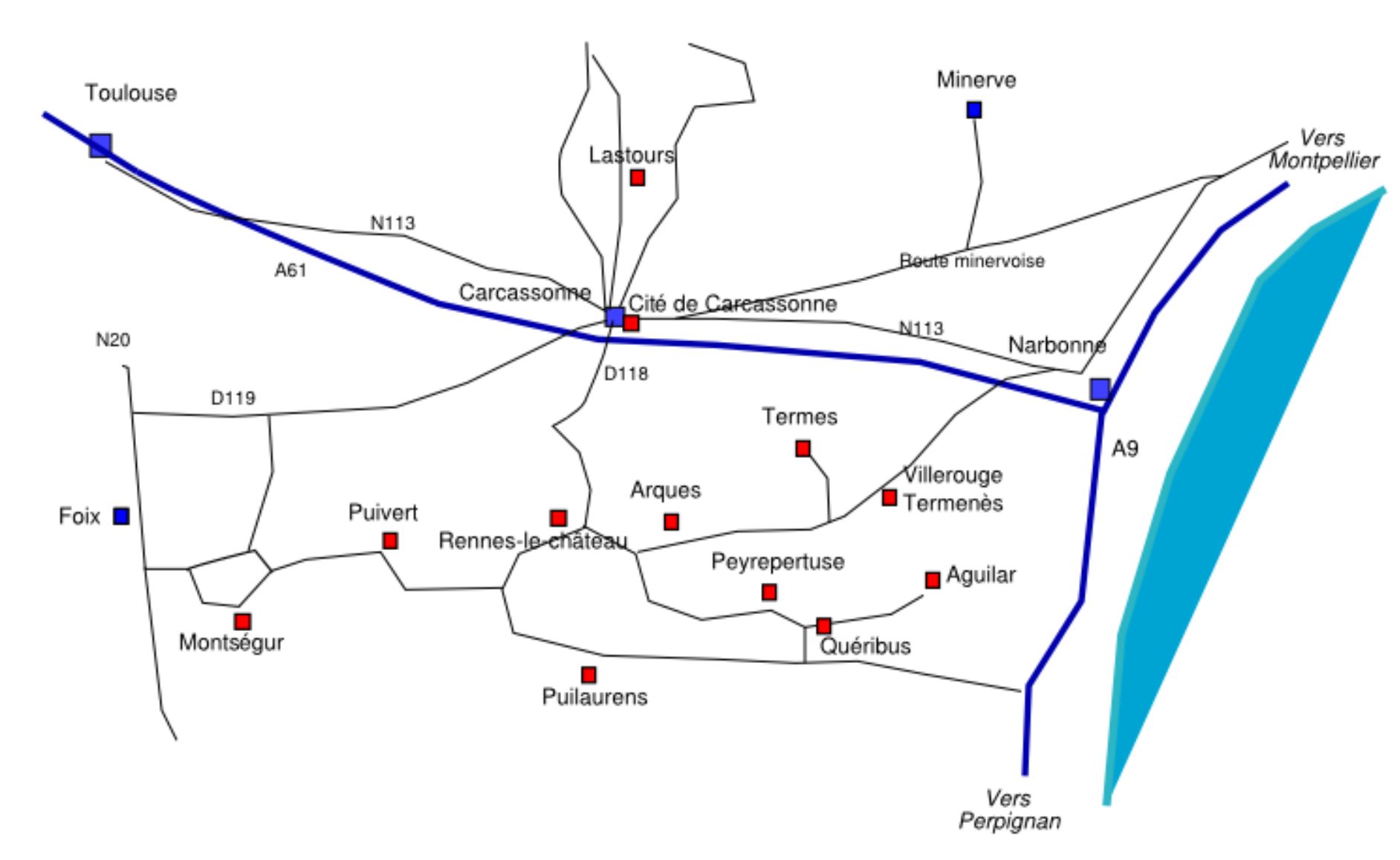

Carcassonne today is the capital of the Aude department in the Occitanie region of southwestern France, about 58 miles from Toulouse. It lies by the “eastward bend” of the glittering cobalt waters of the River Aude, which serves as a barrier between the two towns of the city: the Cité and the Ville Basse. It is the old Cité that attracts most of Carcassonne's visitors (3 million of them each year), for it houses the historic fortress that looks like it came straight out of a fairy tale and supposedly became the muse behind the captivating castles featured in Walt Disney's acclaimed 1959 classic Sleeping Beauty. But this breathtaking town is so much more than just the perfect spot for wedding shoots and social media narcissism, for it is a place that oozes medieval history.

This land is also home to several legends and local traditions. When the earth is drenched by heavy storms, the crumbling red soil drifts into the River Aude, staining the water with crimson. This beautiful, yet haunting phenomenon, which the locals call the “blood of the Cathars,” is a symbolic reminder of the blood shed by these “heretics” at the hands of the Catholic Church.

Despite the controversial events, and their supposed heresy, it seemed that the fall of the Cathars brought an everlasting curse upon the region. As one unnamed farmer, documented by French medievalist Jean Duernoy, put it, “Since the heretics were chased away from Sabartes, there is no longer good weather in this area.” Another notary from Tarn echoed his sentiments, asserting, “When the heretics lived in these lands, we did not have so many storms and lightning. Now that we are with Franciscans and Dominicans, the lightning strikes more frequently...”

In the 16th century, corruption, debauchery, and the general perversion of ethics were running rampant within the Roman Catholic Church. The public began to grow leery of the crooked church, and soon, they could no longer bite their tongues. Among the church's most vocal opponents was Martin Luther, whose publication of the 95 Theses gave rise to the Protestant movement.

This reformed brand of Christianity gradually spread throughout Europe, planting flags across the continent. France was among the first to latch onto the movement, and these new-wave Protestants became known as the “Huguenots.” The exact origins of the Huguenot name is still disputed to this day, but most historians have agreed it is a French and German translation of the Swiss-German term, “eidgenossen,” meaning “oath-fellowship.” The Huguenots mostly resided in the southern regions of France, along with the northern regions of Normandy and Picardy. They shared quite a few similarities with the Protestant Walloons, who lived in what is now Belgium, but the two groups were unique communities. Even so, both groups frequently convened to worship together as refugees.

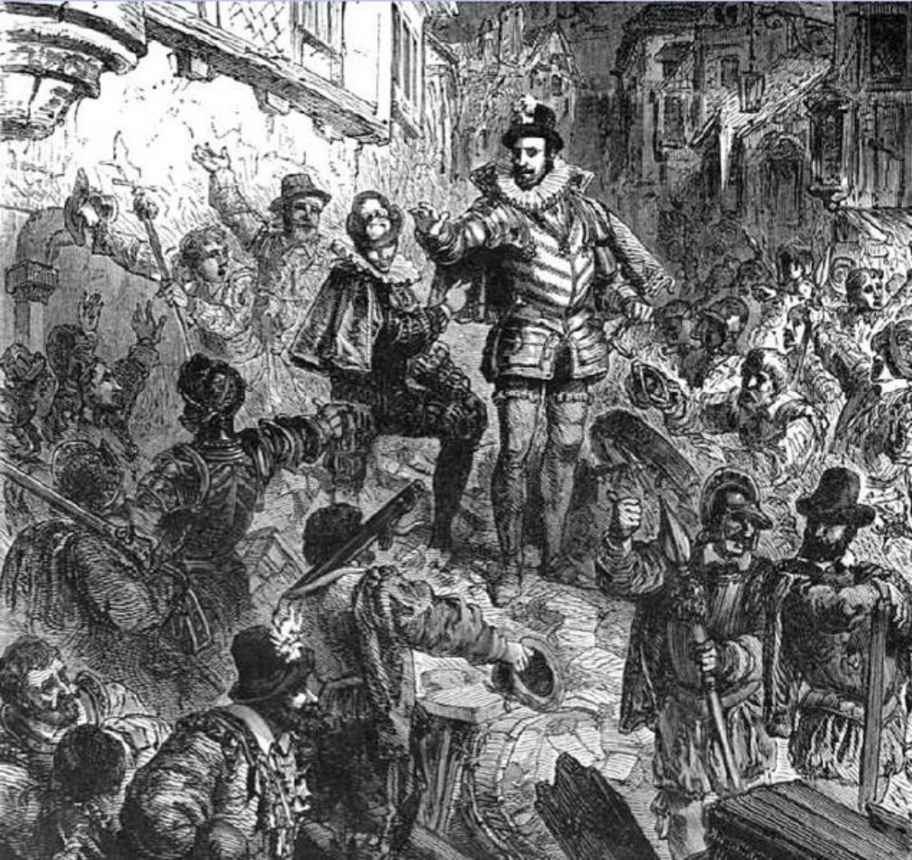

The Huguenots, whose belief system incorporated a blend of unorthodox Waldensian and Calvinist teachings, continued to bloom, which did not sit well with the authorities. Critics attributed the rise of Protestant-led riots to the no-good Huguenots. The Huguenots were known iconoclasts who rejected statues, paintings, idols, and other religious images, as often seen in the numerous statues and stained glass artwork in Catholic churches. Across Europe, rebellious Protestants seized Catholic churches and swiped all heretical images, destroying them with axes and hurling them into roaring bonfires. The string of ambushes included the 1562 Looting of the Churches in Lyon, which were followed by similar attacks in Zurich, Copenhagen, Geneva, and many more.

Even in the face of persecution, the Huguenot influence gained momentum in France. A year before the looting, 2,500 Protestant congregations had already been established across the nation. The Huguenots held their services behind the curtains of secrecy, most commonly in the dead of the night. Some historians believe this clandestine operation could be related to the origin of their name. “Le roi Huguet,” meaning “King Huguet,” referred to purgatory spirits who haunted the living at night. Their perseverance eventually caught the eye of a pallid-faced Venetian ambassador, who purportedly warned his Catholic superiors that “3/4 of France was contaminated with the heretical doctrine.”

The Huguenots' burgeoning power and alleged attempts to infiltrate the world of politics soon alarmed the French authorities. They suspected that these Huguenots were low-profile republicans, involved in a terrible conspiracy to conjure up an uprising to overthrow the monarchy and re-brand France as a federal state. The royal government of France would attempt to tread lightly in the beginning, keeping their hands clean on neutral grounds, but a nightmare was about to unfold.

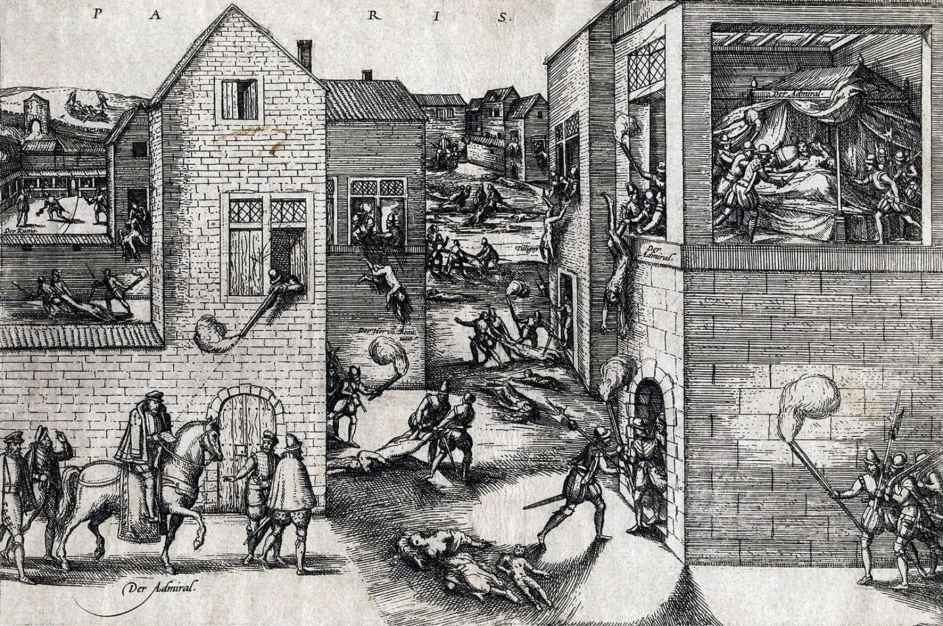

In the 1560s, French authorities called for the violent and bloody persecution of all Huguenots. This hostile period of 36 years, fraught with conflict, upheaval, and civil vendettas between the Huguenots and Catholics, is now known as the “French Wars of Religion,” or simply, the “Huguenot Wars.” A short stretch of peace would later emerge as the wars began to wind down, but bloodshed was once again resurrected by rebellions brought forth by the persecuted.

The Cathars and Huguenots: The History and Legacy of the Major French Christian Groups Who Were Persecuted by the Catholics examines the origins of the groups and the results of the persecution against them. Along with pictures depicting important people, places, and events, you will learn about the Cathars and Huguenots like never before.

The Cathars and Huguenots: The History and Legacy of the Major French Christian Groups Who Were Persecuted by the Catholics

Councils, Synods, and Portentous Preludes

Modern Developments at Carcassonne

Free Books by Charles River Editors

Discounted Books by Charles River Editors

The Legend of Dame Carcas

“Yet could I these 2 days have spent,

While still the autumn sweetly shone,

Ah, me! I might have died content,

When I had looked on Carcassonne.”

“Carcassonne,” – French poet Gustave Nadaud, 1887

Posted by the Porte Narbonne, or Narbonne Gate, the entrance of the fabled La Cite in Carcassonne, is a striking bust that is often missed upon first glance, for it is overshadowed by the exquisitely preserved, millennia-old citadel in its background. But standing before the porte, her face draws one in – round, with plump cheeks, thin arches for eyebrows that follow the shape of her large, downturned eyes, wavy hair peeking out of her wimple – reminiscent of the “celestial” suns with human faces often seen in the bedroom décor of a hip, teenage girl from the '90s. Gaze upon her from a certain angle and distance, and it seems as if one of the iconic conical roofs behind her doubles as a russet-hued hennin.

Garbed in a fine gown with flower accents embroidered on her sleeves and a fussy wimple and veil, the joyfully radiant face that welcomes visitors into the citadel hardly appears to be the “heroine” type. Rather, the way she is depicted here is what usually springs to mind at the mention of a classic damsel in distress. That being said, while this particular damsel was indeed distressed, she relied on no one to not only save herself from the plight at hand, but the entire citadel itself.

This damsel, as inscribed on the plaque underneath the bust, is the beloved Dame Carcas, often billed by the locals as the star of the town's origin story.

A replica of Lady Carcas’s bust

By the mid-8th century CE, the mighty Saracens from North Africa had conquered almost all of Spain, and having triumphantly trekked across the Pyrenees, they were well on their way to ticking off what is now the Occitanie region in southern France. The Moorish Emir Balaak, whose men seized the Carcassonnian castle shortly after their arrival, had moved into the spectacular complex, intending to make it his permanent residence.

Legend has it that the emir, though regarded by his enemies as a bloodthirsty, ruthless heathen of a prince, was anything but. Though aggressive and fearsome in times of war and conquest, Balaak, they say, was a compassionate, merciful man. Contrary to the rumors floating around the district, Balaak did not feast on the hearts of his prisoners, nor did he ornament the castle walls with the rotting, maggot-riddled corpses of his victims. He was charming, kind to his subjects, and reportedly even took it upon himself to educate the children of his prisoners in the “new science of mathematics.”

His wife, the boundlessly wise and diversely gifted Dame Carcas, was just as, if not more adored by their subjects. Carcas was steadfastly loyal and attentive to the needs of her people and what she believed to be the greater good. Obey them, she vowed to her subjects, and no one in the kingdom will ever lay their head to rest with a bare stomach ever again.

The locals took her proposal to heart and heeded the word of their new rulers, and the royals fulfilled their end of the deal. Every echelon of society was well-fed, literacy was on the upswing, and despite the initially rough transition, peace reigned. That was, until Frankish King and Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne began to experience a serious case of castle envy, and became increasingly resentful towards the warm reception Balaak and Carcas were apparently met with. Above all, the emperor refused to accept the idea of “infidel” sovereigns governing the magnificent Carcassonne, which he deemed to be God's land, and pledged to return her to her rightful owner.

Charlemagne, accompanied by a dozen of his trusty paladins and a tremendous battalion of close to 3,000 soldiers, charged down the Montagne Noire (Black Mountain) like a cascade of ants spilling out of their knoll, and headed for the citadel. Meanwhile, the guards from the watchtowers, who had spotted the alarming sight, alerted Balaak and Carcas, who in turn, ordered them to prepare their defenses at once. The Saracen soldiers scrambled into action, but within moments, they were surrounded.

A 9th century coin depicting Charlemagne

The citadel rumbled and rocked with the boulders and other projectiles slamming into the gates and walls of the threatened complex. Arrows and javelins rained from the sky, smiting the hapless soldiers and inhabitants stumbling over each other in the chaos. From the opposite side of the fortress walls came the riotous cries of the Roman soldiers, along with the echoing voice of their leader, Charlemagne, demanding for those inside to surrender.

Though clearly outnumbered, the Saracens, joined by the royals, clambered up to the ramparts and turrets and faced their foes head on. They hurled spears, reciprocated the arrows, and resorted to a series of creative defense tactics, such as hurling at them logs, rocks, and debris, and dumping barrels of boiling water, oil, molten lead, and feces over the walls. “The harder the harvest, the happier the reaper!” a red-faced Balaak reminded his men. “By Allah, my accomplices, we will greatly mow!”

As resolute in their defense as they were, the swiftly dwindling Saracens knew that they could not hold on for much longer. And so, a new plan was hatched. Taking with him what remained of the soldiers, Balaak bade the love of his life farewell and marched out of the citadel gates to confront the assailants, and hopefully, arrive at an understanding. Alas, it did not take long for the negotiations to go awry, and in the resulting bedlam, Balaak, along with every last one of his men, were slaughtered.

Carcas's heart shattered at the news of her husband's death. At the same time, she knew that her people now needed her more than ever, and could not afford for her to lose her head. She promptly gathered all the women, children, and the elderly, and decking them with whatever weapons were left strewn about, ordered them up to the ramparts.

Digging up and donning her husband's old gear, Carcas proceeded to strip the clothes and armor off the dead and dressed up dozens of straw mannequins, which she then placed in turrets and other strategic locations to give the appearance of a fully manned fortress. Utilizing all the knightly training she received as a young woman, she flitted from one mannequin to another, firing arrows and launching spears, scythes, odd rocks, and whatever else that was within reach. The resilient Saracen villagers' battle cries, coupled with Carcas' exceptional agility intimidated Charlemagne's troops into reluctance and inaction, who had (correctly) assumed that they had already killed the last of the Saracen warriors. Charlemagne was so astounded by his foes' hardiness that even he turned to his paladins and declared: “It is a miracle that the warriors continue to dwell there!”

Carcas's strategy, while ingenious, was not built for longevity; it would not take long before those inside began to run out of steam. Charlemagne's men had taken their water supply hostage, and obstructed all exits, thereby preventing any food and supplies from entering the citadel. Even so, as the story goes, Carcas succeeded in holding down the citadel for another 5 years.

Naturally, all things must come to an end. By the fifth year, all the wells inside were completely drained, and only about 30% of the population remained. Worse yet, the crops were long gone, and all the livestock – even pets – were slaughtered for sustenance, all but one bony pig and a tub of sweet corn. The villagers presented the last of the food to Carcas, but rather than sate her growling gut, she beckoned the pig forward, crammed it with sweet corn, and flung the squealing pig over the wall.

Carcas leaned over the parapet, and with bated breath, watched as the overstuffed pig burst on the ground upon impact, its stomach showering Charlemagne and other nearby knights with innards and undigested kernels of sweet corn. The dame delighted in the look of bafflement and defeat on the Christian soldiers' faces. Charlemagne seemed most distraught of all. He grumbled with rage, “This place is overflowing with food! How numerous and vigorous they must still be if they can still give wheat to the most vile beasts!” Believing that they had accomplished nothing with their siege, the dispirited Frankish troops turned around and began the long, grueling journey home.

Needless to say, Carcas was exhilarated by her unlikely victory, and in a fit of glee, she ran a lap around the city, ringing every bell from every tower. The silvery peals of the chiming bells were so loud that they drifted into the distance, and were heard by Charlemagne's men. One of the paladins galloped up to Charlemagne, frantically exclaiming, “Carcas sonne! (Carcas sounds!)” But the emperor, whose eardrums had practically been splintered by the deafening trebuchet blasts, failed to hear anything but the ringing in his ears, and he brushed it off as a collective hallucination. Others say Charlemagne heard the bells crystal-clear, but unable to fathom the thought of being outwitted by a woman, he feigned ignorance and simply told his men to march on, never again to look back...

This, the locals say, is how Carcassonne received her name, but as compelling as this tale is, it is exactly that. On top of the fact that the story fails to coincide with events established by ancient records and historians in the timeline of Carcassonnian history, Dame Carcas herself is a fictitious character, one of a rather modern invention. As maintained by Sylvie Caucanas, the Director of the Departmental Archives of Aude, Carcas made her first appearance in literature as an “allegorical figure” in a poem penned by Jean Dupré in 1534, wherein he creatively lists heroes and heroines that inspired the names of various countries and continents, such as Asia, Europe, Libya, and Mantua.

Be that as it may, this legend resides in a special place in the locals' hearts, for the heroine still lives on in many parts of Carcassonne today. Apart from the bust, there are streets, rustic inns and suites, as well as restaurants dedicated to her, such as the Auberge de Dame Carcas, or the “Hostel of the Dame Carcas.” Attached to it is an eatery that serves an assortment of wines, dark coffees, cassoulet (a type of stew with pork skin and white beans), and honeyed pigs as a tribute to the swine that saved Carcassonne. In the local bakeries one will also find delicious almond cakes, or le petit carcassonnais,” either shaped like castles, or clothed in castle-print wrappers, as well as tins of shortbread biscuits called the “friandises de Dame Carcas (Treats of Dame Carcas).”

The dame is also celebrated annually in the Château Comtal of the medieval citadel. In an effort to keep the tradition alive among the younger generations, the Center for French National Monuments hosts a weekend-long family-friendly extravaganza packed with various workshops, musical and dance performances, treasure hunts, and story-telling that revolved around the Dame's heroics. During Sunday teatime, a massive chocolate pig is carted out to the dining hall in the castle, where it is hammered apart to reveal, not sweet corn, but a horde of miniature chocolate piglets for the children to enjoy.

Of course, all of this still leaves questions. How was Carcassonne actually given its name, and what is it about this enchanting place that reels in millions of visitors every year?

The Dawn of a Great Citadel

“Petit a petit, l'oiseau fait son nid.” (“Little by little, the bird makes its nest”) – ancient French proverb

Even prehistoric humans seemed spellbound by the lush, tillable swathe of land that eventually became Carcassonne, for she appeared to be eternally blessed with pleasant weather, but it was her prime location that sealed the deal. If one were to stand atop her hill, one would be presented with a sweeping view of stunning mountain ranges, habitable valleys, and the verdant Aude plain, which would soon belong to her, and better yet, a bird's eye view of potential trade routes. What would one day become Carcassonne sat on a slab of land sandwiched between a route that connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea, and another that linked the Massif Central to the Pyrenees.

Little information exists about the Neolithic Iberians who archaeologists believe were indigenous to these parts. Prior to the break of the Neolithic Age, mankind roamed the earth with their families, both immediate and extended, as nomads. They were genuine free spirits, albeit more for necessity than for independence-seeking reasons, who lived in interim shelters and lived free of possessions, excluding a few weapons, tools, or whatever they could carry in a pouch. The men hunted beasts and the women collected edible plant life for the entire clan, which was to be consumed in the same day, lest the precious food be spoiled. Once resources dried up and food became scarce, or perhaps, to escape the unforgiving chills of the winter season, they wandered over to their next destination, never staying in one place for more than a couple of months.

The first Neolithic settlement in what is now Carcassonne is estimated to have sprung up sometime between 3500–3000 BCE. The rise of the new age brought about a revolutionary new way of life. These former nomads found permanent homes in this promising patch of land, and gradually developed a society to call their own. Capitalizing on the seemingly bottomless resources around them, they fashioned stone tools through the then-novel concepts of grinding and polishing. They experimented with and eventually created the art of farming, and rather than rely on hunting, learned to domesticate the beasts around them. The flourishing settlement also instituted a primitive version of weaving, as well as pottery making, the latter mostly used to store harvested crops.

About 2,300 years later, the land was inhabited by a tribe with Celtic-Gaulish roots known as the “Volques Tectosages.” The tribe arrived first in the plain and valleys of Roussillon in the Eastern Pyrenees, and from there, poured westward to Toulouse, and later, to the area of Carcassonne. At this time, the land occupied by the Volques settlements, which sat on a plateau to the west of the modern-day Cité measured no more than 25 to 30 hectares (61.8 to 74 acres), just a sliver of the 6,509 hectares under Carcassonnian dominian today.

The tribesmen were among the first to punch deep pits into the earth, otherwise known as silos, to store their grain, which were later transformed into at least 500 silo towers. For shelter, they dwelled in small, simple huts constructed out of clay, straw, and stones, capped with tiled roofs. As innovative as they were, the Volques Tectosages were a superstitious people, and spent much of their time hoarding gold, silver, copper, amber, obsidian, lead ingots, gem stones, beads, and other currencies to appease their pagan gods; only by offering such valuables, they believed, would the gods smile down upon them and bless them with good weather and fortune.

Though much of their day was devoted to collecting these treasures for the gods, the Volques Tectosages opted to live plainly, with austerity and productivity at the core of their culture. Most worked in agriculture, collecting the grains stored in silos and crushing them with stones and wheels to produce cereals. Some tended growing herds of sheep, goats, and pigs. Others prowled about in the woods, hunting deer, boars, and other wild beasts.

Another portion of the population made their bread and butter in trade, working as merchants, clothes-spinners, craftsmen, and so forth. Ceramic workers and pot makers produced a wide array of everyday items, particularly vases, goblets, amphoras for wine and olive oil, and other containers. Blacksmiths produced weapons and tools out of bronze, copper, and iron, and supplied it to the traveling merchants, who then exported the items to Etruria, Greece, and the Iberian Peninsula. By the 7th century BCE, there was so much life in these lands that more than 9% of the previously undisturbed forested land was razed down to make room for more civilization.

A stretch of crudely made clay walls is presumed to have been installed around this vibrant and rapidly growing oppidum, which the locals named the “Carsac.”

About a century later, Carsac was scrapped and abandoned. The inhabitants relocated to the nearby hilltop, and erected a new oppidum there. Having landed themselves one of the most coveted squares of land in all of the Languedoc region, the settlers wasted no time in assembling their defenses. First, another curtain of walls was established around the new town. For added security, a moat measuring about 6 meters (roughly 20 feet) wide and 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) deep bordered the walls surrounding the fortified town.

There was relative peace in the region for the next 400 years, punctuated by a few attempted invasions and minor territorial squabbles here and there, but tensions between the Romans and the inhabitants of central and southern France would soon trigger a major shift within the Carsac community. In the year 122 BCE, the Romans overpowered those in Provence and founded a colony by the Gulf of Lion. Once the colony was firmly established, the Romans journeyed south to Marseille, conquered the inhabitants there, and moved on to the Languedoc region, where they planted more Roman colonies.

It would not take long for the Romans to recognize the strategic significance of Carsac's coordinates. And so, in 100 BCE, the Roman vanquishers swam across the moat, scaled the bulwarks, and drove the inhabitants out of the hilltop. What remained of the natives were assimilated by Roman settlers – more specifically, the Colonia Narbo Martius – who went on to rename their new oppidum the “Colonia Julia Carcaso,” or the “Colony of Julia Carcaso.” It was later shortened to the more melodic “Carcasum.”

By the last quarter of the 1st century BCE, the Roman Carcasum had blossomed into a full-fledged city, with the land on the foot of the hill now incorporated into its ever-growing territory. Carcasum was a thriving administrative and commercial center situated on the Aquitaine Way, and as the capital of the Julia Carcaso colony, presided over the western neck of the River Aude. Nestled between the towns of Narbo (Narbonne) and Tolosa (Toulouse), it was a bustling trading hub that saw the exchange of freshly picked wheat, barley, and other crops, cured meats, amphoras, metals, and sundries, some imported all the way from Montagne Noire, Corbières, and Rouergue.

To better guard their prosperous trading town from roaming pillagers, the Romans built the first stone walls that encircled Carcasum, which was essentially the debut of the Cité. These were the sturdiest bulwarks yet, zigzagging on for about 1,200 meters (1.2 kilometers) and reinforced with distinctive semi-circular towers and secured posterns. Archaeological remnants suggest that the site of Carcasum, at this stage, was no longer just a mere 74 acres but was estimated to have encompassed the bourns of the mountain, and it extended down to the northern end of what the locals called the “Narbonne-Toulouse Road.”

While excavators have been unable to unearth any traces of the public buildings that existed during the Roman-Gallo period, hints of the original construction, including certain sections of the bulwarks, walls, and ramparts, are still visible in the modern fortress. As such, they were able to conclude that the bulwarks were pieced together with squared blocks of sandstone of roughly even weight, thickness, and height, rather than the usual tuff, a type of light, porous rock produced by condensed volcanic ash. The rubble surrounding the fragmented walls in the Roman ramparts on the northern end of the fortress reveal the thin, pale red pieces of the “fired clay” bricks used in their construction. The unique geometric mosaics that garnished the floors also indicate, though not concretely, that the buildings and houses built by the Romans were most likely orthogonal structures.

As it turns out, it was wise of the Romans to strengthen their defenses, for their greatest fear would one day be realized. The Romans at Carcasum managed to cling on to their fortress for a little over half a millennium until the Visigoths, spearheaded by King Theodoric II, conquered Gaul and declared Christianity the official religion, thereby transforming the site into a bishopric. It was in the year 453 CE (according to some sources, 436 CE) that the Visigoths ousted the Romans from Carcasum, which was soon renamed “Carcassonne.” 9 years later, Septimania, the Roman predecessor of the Languedoc-Roussillon region, was ceded to the Visigoths.

Under Theodoric II, Carcassonne was converted to a frontier post, a border checkpoint of sorts for the northern neck of his kingdom. Apart from adding to the Roman-built fortifications and lengthening the crenellated bulwarks, the Visigothic king, a subscriber to Arian Christianity, built one of the first Christian churches in the area, dedicated to Alaric I, first king of the Visigoths. The church was later succeeded by a grand basilica constructed in honor of Saint Nazaire. Another namesake of his was a 2,000 foot tall emerald-green mountain not too far from the fringes of Carcassonne, the Montagne d'Alaric.

Vic Martin’s picture of the mountain

A number of Visigothic leftovers help to shine a light upon their lifestyles. One of their cemeteries, for example, the Moural des Morts, which lies in the thick of a pine forest just 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) away from Carcassonne, is home to 44 stone tombs, laid out in “east to west” fashion. Judging by the size of these graves, even if one were to disregard those that belonged to children, the Visigoths were much smaller in stature compared to the size of an average adult today.

The vestiges of the Visigothic era also supported the fact that they were competent architects and builders, but they were lacking in terms of innovation. For the most part, they replicated Roman blueprints, and did little to improve upon them. That said, they worked expeditiously, and leeching off the designs of the subjugated, they assembled anywhere between 34-40 towers in their time. 2 of these towers, the chapel tower and the 92-ft Tower Pinte, loomed over all, the rest of the buildings in the area shivering in their shadows. In 485 CE, the newly crowned King Alaric II commissioned the renovation of the inner ramparts, instructing the builders to reinforce and expand upon the existing Roman structures.

It was only after securing the perimeters that the Visigoths began work on developing more settlements below the hilltop, which was known as the “Lower Empire,” or today, the Ville Basse. The northern wing was absorbed into the fortifications by extending the bulwarks around them, and visitors can still make out the area of attachment by a castle gate known as “Le Bourg.” It was here in this neighborhood that Christianity flourished, helping bring about a number of different Christian sects.

The Treasures of Carcassonne

“Who ought to be the king of France? The person who has the title, or the man who has the power?” – attributed to Pepin the Short

By the beginning of the 5th century CE, the western half of the Roman Empire was finding it almost impossible to stay afloat. In addition to an economic slump, the formerly flourishing empire found itself targeted by an onslaught of attacks from so-called barbarians, such as the Visigoths, the Ostrogoths, and the Huns. In 410 CE, the once indomitable city of Rome was held hostage by the Visigothic King Alaric. The standoff ended after a period of 3 days, but the humiliating event had tainted its reputation, and it took a noticeable toll on the Romans' morale. Western Roman authorities powered through for some time, but the abrupt deposition of Emperor Romulus Augustulus 66 years later by Flavius Odacer, who then rose to prominence as the first king of Italy, marked the disgraceful fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Following the dismantling of Western Roman Empire, the barbarian kings who had been eyeing the Roman lands competed to chisel out a chunk of the now defunct empire. Among these philistine monarchs was King Chlodovech, also known as King Clovis I. Not only would Clovis triumph in capturing Gaul, he fathered the famous Merovingian bloodline, otherwise known as the “long-haired kings,” a driven dynasty that reigned for more than 200 years.

Clovis was no older than 15 when, upon the death of his father, King Childeric I, in 481, the crown of the Salian Franks was thrust unto him. Despite his young age, Clovis was determined to uphold his revered forerunner's legacy and do him proud.

The Salian Franks were first granted permission by the Romans to settle in the area of what is now Belgium around 358 CE, so long as they agreed to manufacture and equip the Roman soldiers and defend the border on their behalf. It was this relationship fostered by the Franks and the Romans that allowed for the piecemeal “Romanization” of the Franks. Like those who came before him, King Childeric aligned himself with the Romans, and captained numerous campaigns against the Visigoths, Saxons, and other barbaric Germanic tribes. His unswerving allegiance and loyalty to the Gallo-Romans earned their appreciation for him, so much so that several Roman officials inconvenienced themselves with travel to attend his elaborate funeral. Some even contributed to the hoard of weapons, jewels, gilded bees, 15 horses, and other fortunes buried alongside the royal casket.

By the time Clovis was brusquely seated upon the throne, the continent of Europe was a colorful patchwork of religious bodies. Arian Christians, Celtic Christians, Saracens, and pagan monarchs governed extensive strips of land, each committed to their own beliefs, and unreceptive to the then fledgling and wildly disorganized papacy. But the Roman papacy, though far from the powerhouse it would one day become, was every bit as ambitious as they were uncompromising about their creed.

Though the Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Vandals, Suebi, and Alans were technically Christians, they were disciples of Arius, a 4th century Christian presbyter based in Alexandria, Egypt. Arian Christians preached that Jesus, while possessing divine powers, was not divine himself, and was therefore “more than man, but less than God.” As such, all Arians, Celtics, and other “new-age” Christian sects were promptly branded heretics by the Catholic Church. Their unorthodox views, and more importantly, their recalcitrance to the papacy was highly problematic for the Church, for this prevented them from bringing these irreverent and ungodly tribes, and in turn, their territories, under papal control.

Contrary to other Germanic tribes at the time, the Salian Franks were polytheistic pagans who bowed before a bevy of Germanic deities such as Wuotan (Odin), Zio (Mars), and Donar (Thor), among many others. Enter King Clovis I, and these longstanding traditions crumbled. Chroniclers say it was his consort, a Burgundian princess by the name of Clotilda, a devout Catholic in a family of Arians, who “showed him the light,” so to speak. She badgered him endlessly about shedding his convictions and converting to the one true faith.

As told by historian Gregory of Tours, it was in the year 496 that a 30-year-old Clovis agreed to put his dear wife's faith to the test. If the Catholic deity were to ensure his victory over the Alemanni tribes in the Battle of Tolbiac in Germany, he would wash his hands of paganism for eternity and embrace Clotilda's god. Lo and behold, God seemingly did just that, because a few weeks later, the rival king was slain. Clovis's own army suffered crippling losses and barely emerged triumphant over his foes, but the Alemmani grudgingly raised their white flag not long after the loss of their king, and to Clovis, this was enough proof of God's existence. On the 25th of December that year, Clovis commemorated the birthday of Christ by submitting himself for baptism, which was performed by Bishop (and later Saint) Remigius in the cathedral of Reims.

A medieval depiction of the baptism

James Harvey Robinson, author of An Introduction to the History of Western Europe, succinctly summarizes the significance behind the baptism of the Frankish king: “With the conversion of Clovis, there was at least one barbarian leader with whom the Bishop of Rome could negotiate as with a faithful son of the Church...Certainly Clovis quickly learned to combine his own interests with those of the Church, and the alliance between the pope and the Frankish kings was destined to have a great influence upon the history of western Europe.”

The religious discord between Clovis and the rising Arian superpowers, specifically the Visigoths, seeped into the 6th century. These non-secular battles are said to have been the first of its kind. As Henry Hart Milman, who authored History of Latin Christianity, put it, “For the first time, the diffusion of belief in the nature of the Godhead became the avowed pretext for the invasion of a neighboring territory.”

Clovis, who now believed it was his purpose to bring these heretics to heel, initiated a string of military campaigns against these heathens, primarily pinning his focus on the Burgundians to the southeast of his kingdom. Ultimately, he was met with much resistance until 507, when he conquered the Visigoths at Vouillé in central France. Not only did his troops succeed in polishing off the Visigothic King Alaric II, the victory allowed him to annex a vast portion of southwest Gaul. Impressed by the crushing of the Visigoths, Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius bestowed upon the Frankish king an honorary consulship, granting him authority over all other western kings.

Following the devastating defeat, which deprived them of their king, the surviving Visigoths scattered, taking refuge in the remaining Visigothic strongholds. His ego and confidence boosted by the victory at Vouillé, Clovis marched onward to Bordeaux, which he put down with little effort, and camped out there to escape the frigid cold of the winter. Once the ice had thawed, the Frankish troops proceeded to Aquitaine, and later, the Visigothic capital of Toulouse. They seized the territories there, swiping not only Visigothic domains but almost all of their treasure.

Carcassonne was, at this stage, considered a part of the Roman-conceived but now Visigoth-controlled Septimania, a district composed of the following bishoprics: Elne; Agne; Lodève; Béziers; Narbonne; Maguelonne; and Nimes; as well as the Aude and the Languedoc-Roussillon regions.

Some say it was simply Clovis' insatiable hunger for an even bigger kingdom that led him to direct his attention towards Carcassonne. It only made sense for Clovis to set his sights on Carcassonne, for it was no more than 60 miles from Toulouse, and it made for another convenient conquest. Then, there are those who claim that Carcassonne had been the Visigothic pearl the Frankish king had been after from the very beginning, since it supposedly sheltered the very treasure that King Alaric I had stolen from Rome during the sack of the Eternal City in 410.

The contents of the treasure remain a matter of dispute to this day. Some say it was a coffer sparkling with gold, silver, gems, and other stereotypical valuables of the like. The Church, on the other hand, insisted that the Visigoths had made off with the priceless “Treasure of Solomon,” smuggled out of Jerusalem by the Romans themselves from the Temple of Solomon in the latter half of the 1st century CE. The scintillating spoils included a jewel-studded temple table for “showbread,” 4 bronze bulls, a pair of cheribum sculptures, 2 magical gilded candlesticks with a sextet of grooved branches apiece (the Menorah), a medley of cups and vases made out of solid gold, priestly vestments, the Holy Veil, a missorium (a 500 pound diamond-encrusted dish made from pure gold), and other precious furniture.

In early 508, Clovis began the preparations for the attack on Carcassonne, but he did not know that God or good fortune would cease to smile upon him. Among his most grievous errors was charging his eldest son, Theuderic I, with pushing back the Visgothic forces in the Narbonensis and Rhone. While the 24-year-old showed plenty of promise when it came to partaking in battle, he was severely lacking in both the knowledge and experience needed to command it. Consequently, even with the assistance of Burgundian troops who joined him in Gondebaud, the Franks failed to secure the eastern provinces of the Visigoths.

Even so, Carcassonne was anything but unscathed. Frankish troops managed to surround the citadel, and though they were thwarted by the bulwarks, they succeeded in cutting off the Visigoths' water and food supplies for several weeks. In fact, the situation was at one point so dire that the panicking Visigoths reportedly tossed the treasure into the deepest well in the city, desperate to keep the irreplaceable relics out of Frankish hands. But just when it seemed as if the end was near, Theodoric the Great, King of the Ostrogoths and sole governor of Italy, came to the rescue, extending to them the last-minute aid that allowed the Visigoths to repel the Frankish forces.

Unwilling to jeopardize the blue-chip French territories he had worked so tirelessly to attain, Clovis chose to cut his losses and end the siege at Carcassonne. The Frankish troops retreated to Toulouse to regroup, and once their nerve was restored, they moved on to Angouleme, sinking their teeth into the last major town in Aquitaine. Only when Clovis was assured that the Visigoths would be powerless to stop him did he resume his conquests in the remaining areas of Southern Gaul left untrodden by the Franks. Clovis's men headed for Tours, brought the city under their yoke, and confiscated another cache of treasures.

Though Clovis ultimately decided to forgo conquering Septimania, he continued east and later north, declaring Paris his capital. He died in November 3 years later in what would become the City of Lights. By then, the capable king had conquered up to 75% of Gaul.

As per the conditions in the treaty agreed upon by Amalaric, the nephew and successor of the fallen Alaric II, and Athalric, grandson and successor of Theodoric the Great in the 520s, the Visigoths, though permitted to retain the last of their strongholds (including Carcassonne), were made to recognize the authority of the Italian king and present to him the treasures their ancestors had appropriated upon their conquests of the land. Rumor has it that the Visigoths coughed up only a fraction of the Carcassonnian treasure and continued to hold on to the most valuable of the loot, later transferring it to Spain when they finally departed Southern Gaul. But it appeared as if they, too, were not destined to be the last keepers of Solomon's treasure, for when the Saracens raided Spain, they stumbled upon some of the treasure, most notably the missorium and an ornate altar “made of a single emerald, surrounded by 3 rows of pearls, and supported by 60 feet of solid gold,” said to be worth a whopping 500,000 gold pieces alone.

The Visigoths at Carcassonne began to fret when they received word that the capital of their Spanish strongholds, Toledo, had been overrun by invading Muslims in the early 8th century. In the years that followed, the Saracens continued their rampage up and down the length of the country, oftentimes assisted by bitter and forgotten natives who had their lands wrested from them by the vicious Visigoth intruders. By 714, they had established such a presence in the Iberian Peninsula that many began to refer to it by its Arabic moniker, “Al-Andalus.” In just another 4 years, they would practically be in control of the entirety of the Northern Pyrenees. Their unexpected arrival and military dexterity took the Franks by surprise. The Franks, who had been forging forth with a similar campaign of their own at the time, had to delay their own ambitions for a time.

Barcelona and Narbonne – the latter situated on the Via Domitia, just 37 miles from Carcassonne – fell to the Saracen troops in the same year, 720, owing to the direction of Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani, the governor-general of the Al-Andalus. But this Saracen winning streak was interrupted the following year when they failed to capture Toulouse, and their plans were unraveled by the united Aquitanian and Frankish troops. The inglorious episode saw the slaughtering of up to 375,000 Muslim soldiers, Commander al-Khawlani included.

Though their defeat at Toulouse marked one of the worst military losses ever suffered by the Saracens, they remained undeterred. Returning to the Languedoc region in 725, they infiltrated and planted their flags in Carcassonne, Burgundy, and Autun.

For the next 34 years, Carcassonne, or as the Saracens christened it, “Karkashuna,” or “Carcachouna,” was occupied by the Muslim marauders. As for what exactly transpired in the year 759 is still up for speculation. Some revert to the legend of Dame Carcas, substituting Charlemagne with his father, Pepin the Short. While these myth-makers assert Pepin had singlehandedly driven the infidels out of Languedoc, he was outmaneuvered by the Saracen heroine and was thus unable to worm his way into the Carcassonnian fortress. The consensus among most historians, on the other hand, is that Pepin successfully lay siege to Carcassonne and “hounded the Arabs” out of the citadel.

The deaths of Pepin the Short and his younger brother, Carloman I, in 768 and 771 allowed Charlemagne to rule as the solitary king of the Franks. Among his first orders of business was to segregate the enormous empire he had inherited into the following districts: Aquitaine; Septimania (Carcassonne still included); and the Spanish March (later to become Barcelona). He then instituted a “comtal system” to better manage his empire, appointing officials, counts, viscounts, and bishops as the governors of these lands. In exchange for the authority and slew of privileges awarded to them, the counts and viscounts pledged to surrender a majority of the taxes collected to the Frankish crown, and they were permanently on call to defend their lands and other Frankish territories if needed. The first Count of Carcassonne was a noble only known as Bello, the patriarch of the Bellonids, a distinguished dynasty that filled prestigious comtal posts in Catalonia and Septimania for centuries.

Naturally, mastery over the honores (gifts of office, i.e., bishops, counts, and so forth) progressively weakened after Charlemagne's death in late January 814. Frankish territories in the outskirts of the empire leapt on the opportunity to detach themselves from the shriveling empire, eventually securing their independence. Observing this turn of events, the honores, too, began to itch for their independence. The affluent noble dynasties now regarded the lands entrusted to them as “hereditary possessions,” leading to the rise of a “territorial aristocracy.”

The third-in-line to the Carolingian lineage that ruled Carcassonne and Razès was the grandson of Bello, Oliba II. He envisioned the merging of these territories into the County of Barcelona, but it was only following his demise that the system of inheriting honores titles was officially installed. Upon the death of Count Acfred II in 934, the spawn of Oliba II, Carcassonne was passed onto his daughter, Arsenda. The heiress' marriage to Arnold, the Count of Comminges, automatically rendered Carcassonne a realm of Comminges County.

In the decades that followed, the Counts of Comminges preserved the tradition of nepotism that ran rampant across the Midi, unabashedly packing their councils and governments with their sons, brothers, cousins, nephews, and relatives. Finally, in 1068, Count Peter Raymond II broke tradition by divvying up Carcassonne between his 3 daughters.

A year later, all 3 daughters advertised their rights to the twin counties of Carcassonne and Razès, and Agde and Béziers, on the Midi market. Counts from near and far immediately pounced and jostled for the bait, but eventually it was awarded to Count Raymond Berengar I of Barcelona, who presented the enterprising sisters with the most appealing offer: an astounding total of 4,000 mancusos (400 ounces of solid gold). Not long after the deal was sealed, Viscount Raymond Bernard of Albi and Nimes, who was betrothed to Ermengarde, one of the 3 viscountesses, was named the Viscount of Carcassonne. He ruled as such until his brother, Bernard Aton Trencavel, then the Viscount of Albi, Nimes, and Béziers, assumed the distinction in 1082.

Between the years of 1082 and 1209, Carcassonne experienced pivotal progress and expansion under the guardianship of the Trencavels. Besides the further development of city infrastructure and the constellation of construction projects that were commissioned and completed under their watch, the local industries, which centered on wool and wine-making, burgeoned. The robust and continuously growing economy allowed authorities to increase tolls and taxes – at times amounting to half the value of the commodity – which in turn, fattened up the Carcassonnian treasury.

In the 1120s, Bernard Aton, otherwise known as Bernard Ato IV, ordered the construction of the Viscount's castle, or as the locals called it, the “Chateau Comtal.” The site of the grandiose project, which dragged on until 1229, was outlined on a square of land on the western end of the hilltop, “on the highest point of the city.” The castle itself comprised 2 spacious, single-story buildings, a lofty square tower, “arranged at right angles,” hemmed in by wooden palisades on the eastern wing of the castle. Due to the length of its construction, the Chateau Comtal is flavored with a variety of architectural styles, ranging from medieval aesthetics to Romanesque and Gothic touches. The Chapel Sainte-Marie, constructed in 1150, was the private prayer house of the viscounts, and some of the chapel's original semi-circular apse remains visible to this day.

The chateau was shielded by a circuit of crenellated defensive walls, armed with its own set of round watchtowers that guarded the main and rear entrances. The spaces between the rectangular crenellations were used as mountings for archers and other soldiers armed with boulders, boiling oil, and other defenses, with the parapets themselves serving as an efficient screen against the enemies from below. The sturdy stone drawbridge that served as a plank over the cavernous dry moat was raised during times of incursion and war, sealing the castle shut.

On June 12, 1096, Pope Urban II popped into Carcassonne to consecrate the cornerstone and building materials of a new cathedral there, later unveiled as the “Basilique Saint Nazaire and Saint Celse.” The new basilica, which was built atop the foundations of the Frankish church there, would one day become a local landmark, fondly nicknamed the “Jewel of Carcassonne” by the locals.

A statue of Pope Urban Ii in France

In the 1240s, the cathedral underwent a drastic makeover, and was rebuilt in the Gothic style, as ordered by the episcopates of Pierre Rodier and Pierre de Rochefort, and authorized by French King Philip III. The crypt tucked away in the basement of the basilica was added in the late 13th century. It went on to serve as the official church of Carcassonne until the 1800s.

The majestic sandstone structure amazed those who laid their eyes upon it. Its yellow brick facade, crowned with miniature crosses, and adorned with floral cutouts, seemed to shimmer under the sunlight, as if coated with a layer of gold. The layout of the cathedral itself was shaped like a Latin cross, measuring about 59 meters (194 feet) from one end to the other. The transepts, or arms of the church, were about 36 meters (118 feet) in length, and the nave, which housed the congregation, about 16 meters (52.5 feet) in width. Last, but not least, was arguably the highlight of the cathedral – its gorgeous collection of delicate stained glass windows. Apart from the ornamental windows that cast dreamy, rainbow-like shadows in floral and geometric patterns on the floors of the church, were the floor-length windows featuring 16 biblical scenes pertaining to Christ, such as the Adoration of the Magi, the Crucifixion, and the Descent of the Cross, among others. The whimsical gargoyle water spouts sprinkled about the church are yet another feature that grips the attention of all visitors alike.

Dreading another repeat of history, the Trencavels erected the last line of defense in the early 12th century, around the year 1130. The moat was deepened, and the winding bulwark that fenced in the Cité was augmented so that it was now more than twice the length of the Roman wall, expanding from 1,200 meters to over 3,000 (1.86 miles). Another 13-19 towers, topped with terracotta-tiled roofs were added to the new segments of the bulwarks, so that it now amounted to a total of 53. The 4 barbicans mounted onto the 4 gates of the city were patched up and reinforced. Matacanes, or hoardings, which were either ring-shaped wooden galleries or tunnel-like passageways hovering 130 feet above ground, were also built. These allowed for soldiers to launch missiles and other projectiles at their assailants below.

A picture of the fortified wall

A picture of a reconstructed hoarding at Carcassonne

The Cité was also split into 16 châtellenies, or lordships. Each châtelain was to guard 1 or 2 towers, as well as the parts of the bulwark that flanked the towers in question. A pair of boroughs, Saint Michael and Saint Vincent, each a component of the 16 châtellenies, were established just outside the Carcassonnian borders. Inhabitants and soldiers stationed there were also expected to maintain the castles and defenses assigned to them for extra security.

The Origins of the Cathars

“We must no more ask whether the soul and body are one than ask whether the wax and the figure impressed on it are one.” – attributed to Aristotle

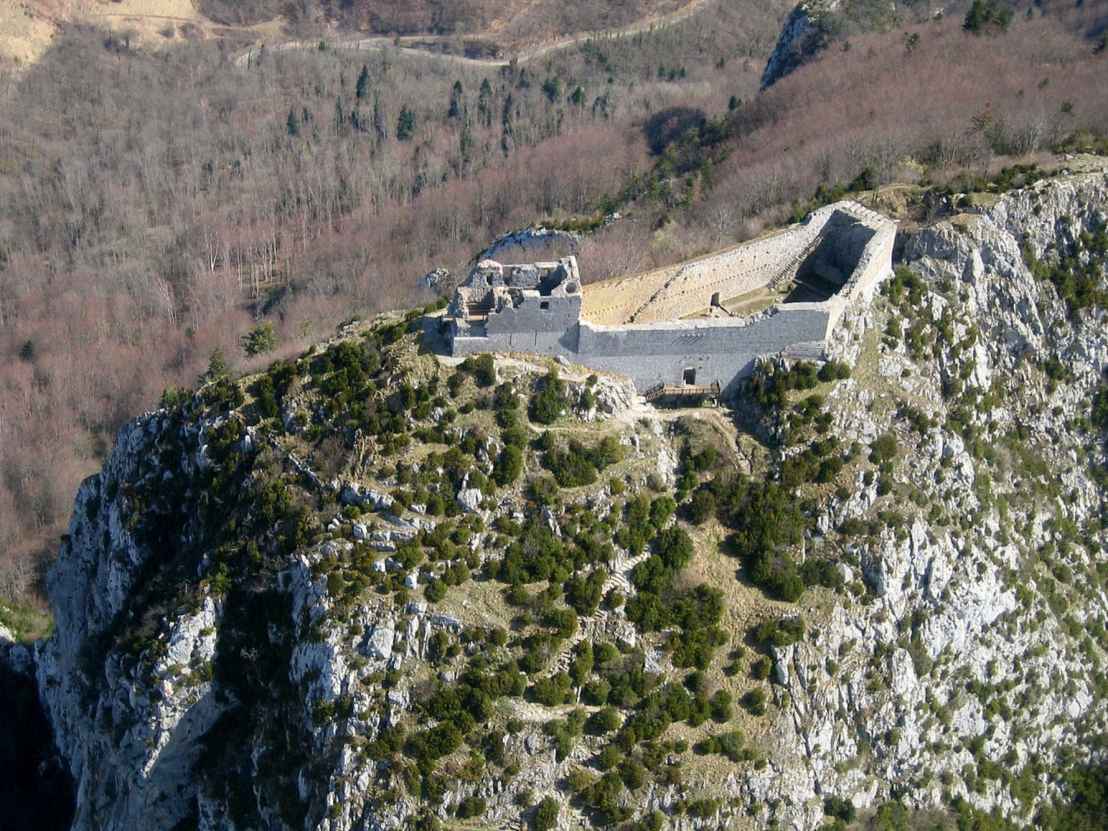

Nestled within an evergreen grove blanketing the crest of a hill 4,000 feet above the Montségur village stood its namesake – a strapping, sandy-beige fortress guarded by imposing walls and capped with a melange of gable and conical roofs. From below, there was little one could see of the colossal castle, or as the locals called it, the Château de Montségur, perched upon the round boulder of a hill. Not only was it half-hidden by the hill's natural formations, what was visible blended in with the naked rock, so that it appeared no more than a distinctive stone protuberance jutting out of its pinnacle. But if one were to lean against the parapet in the highest point of the castle, one would be treated to a panoramic view of the lush valleys and countryside of the Ariège, along the Pyrenees, the Montagne Noire (Black Mountain), and even parts of Toulouse.

M. Danis’ aerial picture of the Château de Montségur

The courtyard

It was a particularly pitch-black evening on the 16th of March, 1244. The dainty breeze of the approaching spring caressed the mossy walls of the castle. The vibrant wildflowers surrounding the structure swayed slightly with the wind, but otherwise resembled static fireflies hovering above the grass. This scene would have been pretty as a picture had it not been for the discordance of tumbling targets, whizzing projectiles, and other telltale signs of a siege in the distance. Critters usually seen scurrying about freely were cowering in their burrows. Even the stars that usually ornamented the twinkling sky were nowhere to be seen, as if shrinking from the horrors that were unfolding below them.

There was movement inside of the castle, inhabited by some 300 people, but curiously, it was not one of alarm, nor of urgency. Some shuffled about aimlessly by their lonesome, their eyes glazed over and their faces void of expression. Families and loved ones were huddled in corners, their eyes squeezed shut as they muttered last-minute prayers under their breaths. Others were locked in an embrace, whispering words of comfort to their pale-faced companions.

They were cold, numb, and frightened, but there was a haunting sense of peace in the air, for most had resigned to their irreversible fates. They had only mere minutes, perhaps even seconds, to make the life-changing decision looming over them. Were they going to renounce their beliefs and everything that they stood for, or were they willing to become martyrs of what they trusted to be the one true faith?

As these wretched souls awaited their impending doom, however, a band of 3 or 4 elders, accompanied by a local guide, silently headed for the ramparts in the rear of the castle. Cloaked in scratchy woolen blankets, the men pussyfooted to the sturdiest parapet, knotted some sheets around the merlon, and braving the height, rappelled down the side of the wall. They then scampered over to the nearby promontory, and using their sheets, shimmied down to the Lasset gorge.

Not long after they hit the ground, a group of mysterious, similarly cloaked men, faces concealed in their hoods, emerged from the shadows. These were common vassals from the nearby Canton of Sabarthès, who claimed to be the “Sons of the Moon,” more precisely, of the moon goddess, Belissena. Though not a word was exchanged between them, each party knew what was expected of them.

With the tick of the proverbial clock ringing in their ears, one of the elders fished out a parcel tucked inside of his cloak, and handed it over to the vassals. And with not a second to spare, the parties parted ways, away from the stampede of soldiers descending to the gorge. The vassals, the new guarders of this priceless treasure, scuttled back into the shadows. The elders, on the other hand, scaled the cliff side and ducked into one of the hundreds of caves in Sabarthès, never to be seen again.

These elders, along with the rest of the unfortunate souls trapped inside the fortress, were none other than the Cathars, and those soldiers were the underlings of the Roman Catholic Church.

Exactly what this priceless treasure was – as well as its existence – continues to be a matter of debate. Some say it was a green jade bowl that possessed otherworldly powers, or maybe, quite literally, just a chest brimming with gold, silver, jewels, and other glittering valuables. Some claim it was a cryptic manuscript comprising the esoteric teachings and other secrets of the Cathars, one so expertly stowed away that it remains missing. Some are convinced that the treasure was of far more significance, one so significant, in fact, that the search for it is one that still persists to this day.

Others insist that it was the fabled Ark of the Covenant that the Cathars handed to the vassals. This 3,000-year-old Biblical artifact, constructed by the Israelites, was believed to be a splendid wooden case coated in gold and garnished with a pair of gilded angels, containing the original stone slabs of the 10 Commandments. It was by some miracle that the Cathars were able to lug that hefty chest all the way down to the gorge.

Then comes what is by far the most popular theory, which identifies the treasure as the Holy Grail. It is an opinion so widespread that Château de Montségur has unofficially been dubbed the “Holy Grail Castle.” The Grail in question, still prevalent in modern pop culture, belonged to Christ during the Last Supper, and it was the same chalice Joseph of Arimathea used to bottle the blood of the crucified Christ. Like the sacred Ark, the Grail is often associated with miracles and other supernatural occurrences, such as the feeding of 4,000 with a dozen loaves of bread, and a sinkhole that consumed a disobedient relative of Josephus (son of Joseph of Arimathea), amongst many others.

Whether or not this treasure exists is up for debate, but the atrocities directed toward the Cathars that very evening, as historical records show, cannot be denied. Of course, this begs the question of why the Catholic Church was so determined to annihilate them.

Since most, if not all the Cathar texts were torn to shreds by the Church, their origins can only be left up to speculation. One of the lesser-known etiological myths revolves around Jesus and alleged reformed prostitute, Mary Magdalene, who is oftentimes depicted with an alabaster jar for having famously bathed the feet of Christ with Nardus oil. Following the death and resurrection of Christ, the 12 apostles scattered themselves in all directions to faraway lands, traveling as far as what is now modern day Turkey and India. In the year 44, Mary Magdalene herself was charged with conspiracy against the Roman sovereigns and shunned from her homeland. The road ahead was daunting, but Mary's resilient spirit remained unshaken.

As the Gospel tells it, it was Mary who instilled in the disciples the boundless courage needed to complete their mission. The disciples asked, “How shall we go to the Gentiles and preach the Gospel of the Kingdom of the Son of Man? If they did not spare Him, how will they spare us?” Without missing a beat, Mary sprung up to her feet and commanded her brethren, “Do not week and do not grieve, nor be irresolute, for His grace will be entirely with you, and will protect you.”

The legend continues with an unmarked, shoddily made ship sans sails and oars drifting towards and eventually running aground a shore in southern France. One by one, Mary Magdalene, Mother Mary, and her sister, Mary of Clopas piled out of the ship, followed by Lazarus, Martha, and a servant girl named Sarah. The site of their landing, the capital of the Camargue, is now aptly known as the “Saintes Maries-de-la-Mer,” or in English, the “Holy Marys from the Sea.” Endowed with the honorable task of spreading the word of the Lord, each one of them started towards, and eventually set up camp in a different region of France.

Catholics suggest that Mary Magdalene wound up in the Roman region of Provence in southeastern France, where she reportedly converted all its inhabitants, including the royal family, to Roman Catholicism in no more than 24 hours. She then retreated to the sacred woods now called the Sainte Baume and found shelter inside a cave in the thick of the forest, where she spent the remaining 3 decades of her life. Subsisting on nothing but the bread of the Holy Eucharist, provided to her every day by visiting angels, Mary spent every waking hour either in deep prayer or meditation. Once she took her last breath, the angels swooped into the cave and removed her body.

In the Cathar version of the tale, Mary Magdalene did not end up in Provence but in historical Rennes-les-Bains in what is now Occitanie in southern France. More importantly, according to the Cathars, Mary was not alone; traveling with her was Christ himself, who never died from the crucifixion. As the story goes, Mary crept into his tomb 40 hours after his “death,” and together, the pair were secretly whisked away to France.

The Cathar edition also advocates an age-old conspiracy theory that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were husband and wife. Some say that the pair resided in a humble cottage on a hilltop, while others maintain that they lived right in the heart of the community, preferring to live close to those whose hearts they aimed to touch. Rumor has it that some of the townspeople had even chanced upon them in the marketplace and other parts of town, with a few of them swearing that they had also made small talk with them.

Evidently, the pair did not merely adopt the title of husband and wife to fool the townspeople regarding their true identities. The Cathars asserted they then became parents to at least 3 children, two sons and a daughter. The pair lived simply and piously in their cozy cottage until they received word of the townspeople's growing suspicions and interest in their pasts.

It was then that the couple chose to split up. Mary brought with her one of their sons and made the trek up north to what would become Languedoc (the County of Toulose). Joseph of Arimathea was summoned to collect their other son, after which he was dispatched to England. Lastly, Jesus, along with their only daughter, opted to relocate to a more remote residence in the countryside of Rennes-le-Château.

When the hallowed children came of age, they were instructed to go out into the town and preach to the locals the revised doctrine, which gradually evolved and branched out into an array of religious sects and organizations, such as the Essenes, the Knights Templar, and the Cathars. The sons also spawned the bloodlines of the later ruling Arthurian and Merovingian kings in their respective regions. As such, those who propagate these stories say it was the family tree, authentic records, and other proof pertaining to the “perpetuation of the Jesus bloodline” bequeathed to the Cathars that the priests entrusted to the vassals for safekeeping.

While these myths are certainly intriguing, the majority of historians believe that Catharism most likely stemmed from millennia-old Gnostic religions from the East centered on “Dualism.” As Bishop Walter Mapp, author of De Nugis Curialium (“Trifles of Courtiers”), put it, “Everywhere among Christians [the Cathars] have lain hidden since the time of the Lord's Passion, straying in error.”

But even the concept of Dualism itself transcends the birth of Christian Gnosticism, said to be founded by Valentinus of Carthage in the 2nd century CE. The “radical opposition of spirit and matter, good and evil, male and female,” as English historian Steven Runciman explains, is “as old as mankind.” For instance, there are the harmoniously contrary, yet parallel forces of the yin and yang in Taoism, which bears no link to Christian Gnosticism. The phenomena of good and evil, as well as the conflicting idea of a benevolent God and the evils of material existence, have also been tackled by a host of ancient philosophers, such as the Greek Stoics, Hermetic thinkers, and Jewish scholars from Alexandrian times.

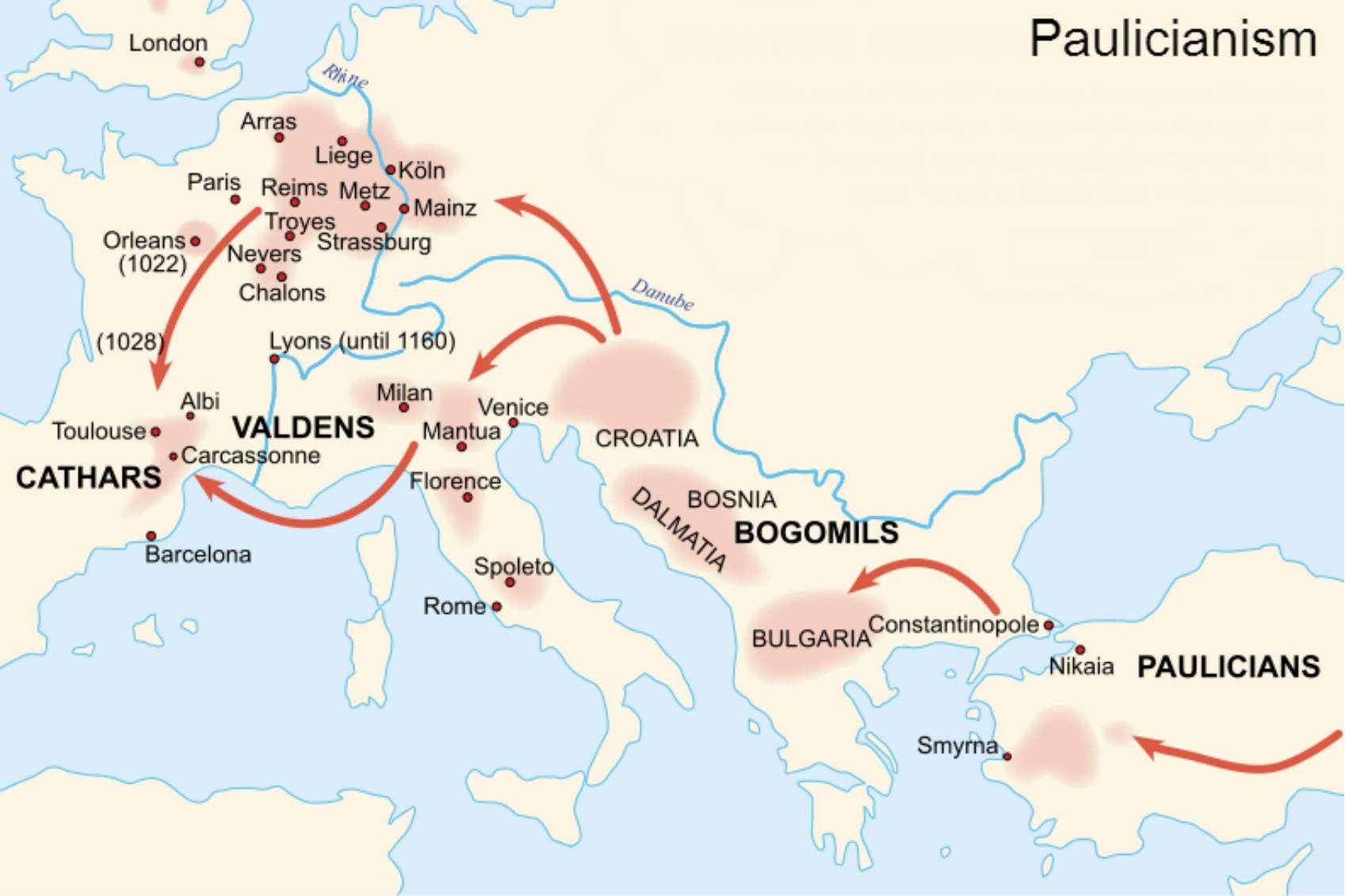

Chroniclers have now concluded that it was from the religion and beliefs of the Bogomils in the Balkans that Catharism descended. The Bogomils were inspired by the Paulicians of Armenia, the latter especially prominent in ancient Armenia between the mid-7th century to late 9th century CE.

The Gnostic Paulicians, in turn, borrowed much of their creed from Manichaeism. Manichaeism, the brainchild of a Persian aristocrat known only as “Mani,” was instituted sometime in the 3rd century. The Babylonian sect hosted a distinctive bilateral hierarchical system composed of the Elect, which was a body of high-ranking spiritual leaders selected by the clan, and Hearers, the stock members of the group. The belief system of the Manichee, which guaranteed salvation through the spiritual knowledge passed down by Mani, was an amalgam of Gnostic Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Taoism, and a slew of other mystical theologies, its multifaceted character attracting both admirers and critics.

According to its designer, there are two “natures” that have ruled the earth since the beginning of time – light and darkness. On the one hand, the kingdom of light is marked by serenity and peace of mind, whereas the domain of darkness is in endless war with itself. The creation of the universe, as the designer asserted, was a product of these clashing elements.

Given that stiff discipline was among the core values of the Manichee, members were expected to abstain from swearing, and they were to be strict vegetarians. Their equal treatment of women, which was highly uncustomary at the time, was another norm shattered by the clan. Women, too, could be appointed as members of the Elect.

The Paulicians, another dualist sect, also promoted the belief of two primary forces: good and evil. As the material world was believed to have been a consequence engendered by evil, the Paulicians pledged to distance themselves from all material and carnal pleasures, and shed all vices. Thus, all members swore off meat and alcohol, and vowed to live a life of celibacy.

Much of the information about the Bogomils that exists today is potentially skewed, for the bulk had been gathered by their opponents, i.e., Christian Churches. It is believed that Bogolism came to the fore in the Balkans (now Bulgaria) in the middle of the 10th century, bred by the sect's creator, a priest named Bogomil. The Interrogatio Iohanni, the only Bogomil literature known to have survived, preaches a belief system closely aligned with Manichean and Paulician principles in terms of asceticism and dualism.

Contrary to the aforementioned persuasions, the Bogomil belief system relied heavily on Christian themes. Bogomil intended for them to hark back to the earliest, and therefore “purest” form of Christianity, before the rise of what they deemed the increasingly tyrannical Roman Catholic Church. Members were educated about the Gnostic notion of Docetism, which saw Christ as solely a celestial being; this meant that Christ never physically existed, and that his trials and sufferings on earth may have been allegorical. The world, the Bogomils believed, was not an invention of the “God of Light,” but His rival, the wicked “Abrahamic God.” They rejected crosses and crucifixes alike, and preferred to conduct their rites amidst nature.

It was in the early 1000s that Bogomilism spread to the Byzantine lands, where they grew and soon blossomed. They would have an exceptionally notable presence in Constantinople; in fact, by the end of the century, this “heretical” cult had become so regionally predominant that local leaders, threatened by their influence and proliferation, authorized a brutal campaign against them, a tactic employed by various leaders throughout history. In the year 1118, a ring of Bogomil clerics were rounded up, found guilty at trial for the crime of heresy, and sentenced to death by Emperor Alexius I Comnenus. Among those executed was Basil the Physician, head of the Bogomils.

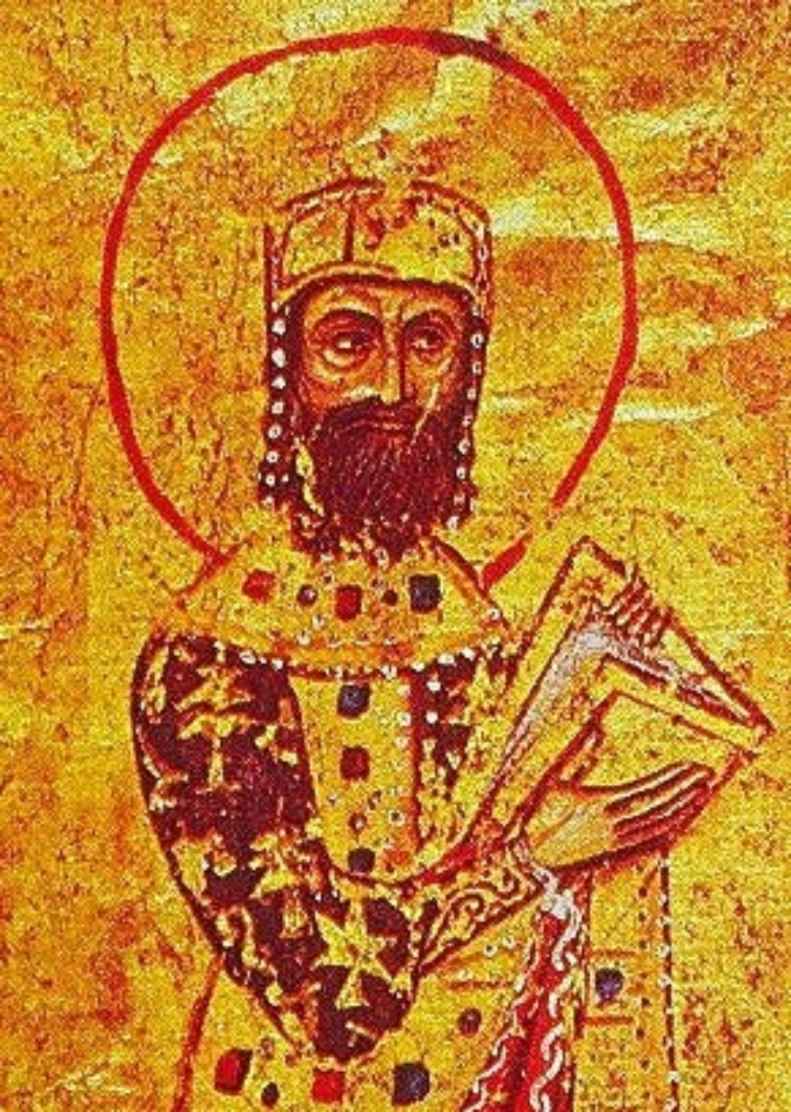

A contemporary portrait of the Byzantine emperor

In spite of the marked resistance against them, Bogomilism continued to flourish, even extending their reach to Serbia and Bosnia before it was flushed out by Islam following the fall of Constantinople in the 15th century.

Bogomilism made its way to northern Italy by immigrant charcoal burners and other societal outcasts. Through word of mouth, it was then peddled by traveling merchants and Gnostic preachers to civilians in neighboring and distant Italian villages. Their operations naturally shifted to southern France, brought to the region by an unnamed Italian woman, and later, to the villages in northern Spain.

The Bogomil movement was greeted with unexpected warmth and met with surprising success in France. Their fruitfulness was such that more and more converted Bogomils began to discuss and dissect its constitution, which gave way to the advent of an allied, but separate school of thought. It was then that a new denomination, which came to be known as “Catharism,” was established. Though the Bogomils and Cathars often held different and sometimes outright contradictory opinions on certain doctrines, the relationship between the sister sects was an amicable one.

As opposed to the other dualist religions, the muse behind the name of the Cathars has not yet been determined. Some say that the name was directly lifted off an older, but then extinct (or perhaps the true predecessor of) sect called the “Cathari,” derived from the Greek word “katharoi,” which translates into “the pure ones.” In the book of St. John Damascene, On Heresies, he makes a reference to the sect: “They absolutely reject those who marry a second time, and reject the possibility of penance [that is, forgiveness of sins after baptism].”

The Ecumenical Council of Nicae, which convened in 325 CE, makes another direct mention of this controversial sect in Canon 8: “...if those called “Cathari” come over [to the faith], let them first make profession that they are willing to communicate [share full communion] with the twice-married, and grant pardon to those who have lapsed...”

Allusions to the new-age French Cathars in literature were first made in 1143. A new brand of heresy had been introduced to France by foreign sacrilegious renegades, warned author Everwinus of Steinfeld, who pushed wildly unorthodox theories from Greece that distorted unquestionable Catholic principles. But it was only 22 years later that Eckbert von Schönau mentioned them by their designation, the “Cathars,” and elaborated on their dualist beliefs.

The first known complaint lodged against the Cathars by a “concerned” layman was filed in 1177. In a letter addressed to a Cistercian abbot, Count Raymond of Toulouse seeks advice on how best to handle the irreverent “two-principled” heretics that had been running amok in his city. As a result of Raymond's report, a number of accused Cathars were interrogated and duly punished.

By then, the war against the heretics in these parts was nothing new. Toulouse, along with the other localities between the Rhone and the Pyrenees, had been rife with tensions between the Catholic Church and the so-called heretics for hundreds of years. Gnostic sects that labeled Jesus as a mortal prophet and challenged his divinity, such as the Manichee, Bogomils, and Cathars, aroused the most contempt from the Catholic Church, and were among the first names on the establishment's blacklist.

From northern Italy and southern France, Catharism spread to the north of the kingdom. When the strongholds erected there began to flourish in the mid-1100s, the movement traveled further north to the Rhineland cities, gaining remarkable traction in Cologne. But it was in Languedoc that the Cathars truly found their footing, considered by many to be one of the first nerve centers of the community. Indeed, their operations there were so productive that by the end of the 1100s, a majority of the formerly Catholic citizens had converted to Catharism.

Leo Freeman’s map of the spread of the sect

Though this new variety of Catharism remained absent from literature until halfway into the 12th century, its members and their ancestors had already endured grievous injustices and abuse at the hands of the Catholic Church for at least more than a century beforehand. Between the years of 1018 and 1028, suspected Cathars, lumped together with the local Manichee by ignorant Church authorities in Aquitaine and Toulouse, became subject to extreme scrutiny. On the 28th of December, 1022, the Feast of the Holy Innocents, 13 Cathar/Manichee elders were arrested in Orléans and condemned to death for their unconventional views on marriage and idolatry, amongst other beliefs. Many incongruous and unfounded yet accepted rumors about the cult's practices, which included members partaking in devil worship, orgies, excessive boozing, and other debauchery, solidified the verdict.

In medieval Europe, one's style of execution was dictated by their crime. Thieves, for example, were sent to the gallows. Adulterers and prostitutes were punished in biblical fashion, and stoned to death for their sins. Those who murdered children were impaled by stakes, their corpses later displayed to the public like trophies. Counterfeiters and con artists were thrown into a vat of bubbling oil and boiled to death. Assassins found guilty of regicide were drawn and quartered.

Death by fire, as it turns out, was a dreadful punishment made exclusive to the heretics. While clearly a needlessly excruciating and traumatic means of execution, it was marketed by the Church as a way to reverse the evil in these “corrupt” souls, as well as to prevent their depravity from infecting the good Christian public. Only by fire, declared Church authorities, could the “smallest trace of sin...and evil” in the ungodly dissenters be thoroughly eliminated. Even the bodies of those who had died of natural and other causes but were posthumously proclaimed as heretics were exhumed and cremated. What's more, the incineration of the heretics' corpses ensured that they would never find the eternal salvation promised to obedient, God-fearing Catholics, for a proper burial was required for resurrection.

The Church leaders at Orléans were set on making an example out of the audacious dissenters. One by one, the shackled prisoners limped in single file to their site of execution as a mob of jeering bystanders pelted them with rotten fruit. Even the queen herself, Constance of Arles, took part in the riotous behavior, ramming her staff into the eye of a passing Cathar named Stephanus. The condemned were marched into a menacing wooden building at the end of the road. All doors, windows, and possible exits were then sealed shut, and the entire building was set ablaze.

An excerpt from R. I. Moore, author of The War On Heresy: Faith and Power in Medieval Europe, paints a chilling picture of the events: “[W]hen the flames began to burn them savagely, they cried out as loudly as they could from the middle of the fire that they had been terribly deceived by the trickery of the devil, that the views they had recently held of God and Lord of All were bad, and that as punishment for their blasphemy against Him, they would endure much torment in this world, and more in that to come...” The cries of the roasting victims were so distressing that a few rushed forth in a futile effort to extinguish the roaring flames, until they finally accepted that like all the doors and windows on the burning structure, their fates were sealed.

The horrendous events of the 28th of December provided a macabre milestone in European Christian history, for they were supposedly the first burnings of heretics since the 500s. As it turned out, the worst was yet to come.

Creed and Convictions

“But we impart a secret and hidden wisdom of God, which God decreed before the ages for our glory.” – 1 Corinthians 2:7

In order to better understand the tempestuous relationship between the Cathars and the Catholics, it is best to analyze the former's nonconformist belief system.

For starters, not only did the Cathars argue that their belief system predated that of the Roman Catholic Church, they maintained that they were “good Christians,” which their rivals saw as not just an implication, but proof of the Cathars' supercilious and profane character. Likewise, the Cathars seemed to make no attempts at masking their distrust and loathing of the Catholic Church, which they thought had consciously strayed from the customs and practices of the “Early Church” and generated a conniving and iniquitous system that indulged only the needs and wants of those at the top of the pyramid.

To the Cathars, traditionally classified as Christian Dualists, the “Good God” created, and as such, presides over all that is pure and intangible, meaning all souls – earthly and otherwise – light, love, kindness, and so on. The human race consists of ageless, recycled souls, or as the Cathars called them, “divine sparks.” Humans, they claim, are no more than “sparks” or “angels” trapped in vessels of flesh. There were some who believed that the stars they saw strewn across the night skies were other “divine sparks” in heaven, watching over the flock on Earth.