SECTION I

Guide To Efficient Exam Preparation

“I don’t love studying. I hate studying. I like learning. Learning is beautiful.”

—Natalie Portman

“Finally, from so little sleeping and so much reading, his brain dried up and he went completely out of his mind.”

—Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quixote

“Sometimes the questions are complicated and the answers are simple.”

—Dr. Seuss

“He who knows all the answers has not been asked all the questions.”

—Confucius

“It’s what you learn after you know it all that counts.”

—John Wooden

“A goal without a plan is just a wish.”

—Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

“I was gratified to be able to answer promptly, and I did. I said I didn’t know.”

—Mark Twain

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Relax.

This section is intended to make your exam preparation easier, not harder. Our goal is to reduce your level of anxiety and help you make the most of your efforts by helping you understand more about the United States Medical Licensing Examination, Step 1 (USMLE Step 1). As a medical student, you are no doubt familiar with taking standardized examinations and quickly absorbing large amounts of material. When you first confront the USMLE Step 1, however, you may find it all too easy to become sidetracked from your goal of studying with maximal effectiveness. Common mistakes that students make when studying for Step 1 include the following:

Starting to study (including First Aid) too late

Starting to study (including First Aid) too late

Starting to study intensely too early and burning out

Starting to study intensely too early and burning out

Starting to prepare for boards before creating a knowledge foundation

Starting to prepare for boards before creating a knowledge foundation

Using inefficient or inappropriate study methods

Using inefficient or inappropriate study methods

Buying the wrong resources or buying too many resources

Buying the wrong resources or buying too many resources

Buying only one publisher’s review series for all subjects

Buying only one publisher’s review series for all subjects

Not using practice examinations to maximum benefit

Not using practice examinations to maximum benefit

Not understanding how scoring is performed or what the score means

Not understanding how scoring is performed or what the score means

Not using review books along with your classes

Not using review books along with your classes

Not analyzing and improving your test-taking strategies

Not analyzing and improving your test-taking strategies

Getting bogged down by reviewing difficult topics excessively

Getting bogged down by reviewing difficult topics excessively

Studying material that is rarely tested on the USMLE Step 1

Studying material that is rarely tested on the USMLE Step 1

Failing to master certain high-yield subjects owing to overconfidence

Failing to master certain high-yield subjects owing to overconfidence

Using First Aid as your sole study resource

Using First Aid as your sole study resource

Trying to prepare for it all alone

Trying to prepare for it all alone

In this section, we offer advice to help you avoid these pitfalls and be more productive in your studies.

USMLE STEP 1—THE BASICS

USMLE STEP 1—THE BASICS

The USMLE Step 1 is the first of three examinations that you must pass in order to become a licensed physician in the United States. The USMLE is a joint endeavor of the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) and the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB). The USMLE serves as the single examination system for US medical students and international medical graduates (IMGs) seeking medical licensure in the United States.

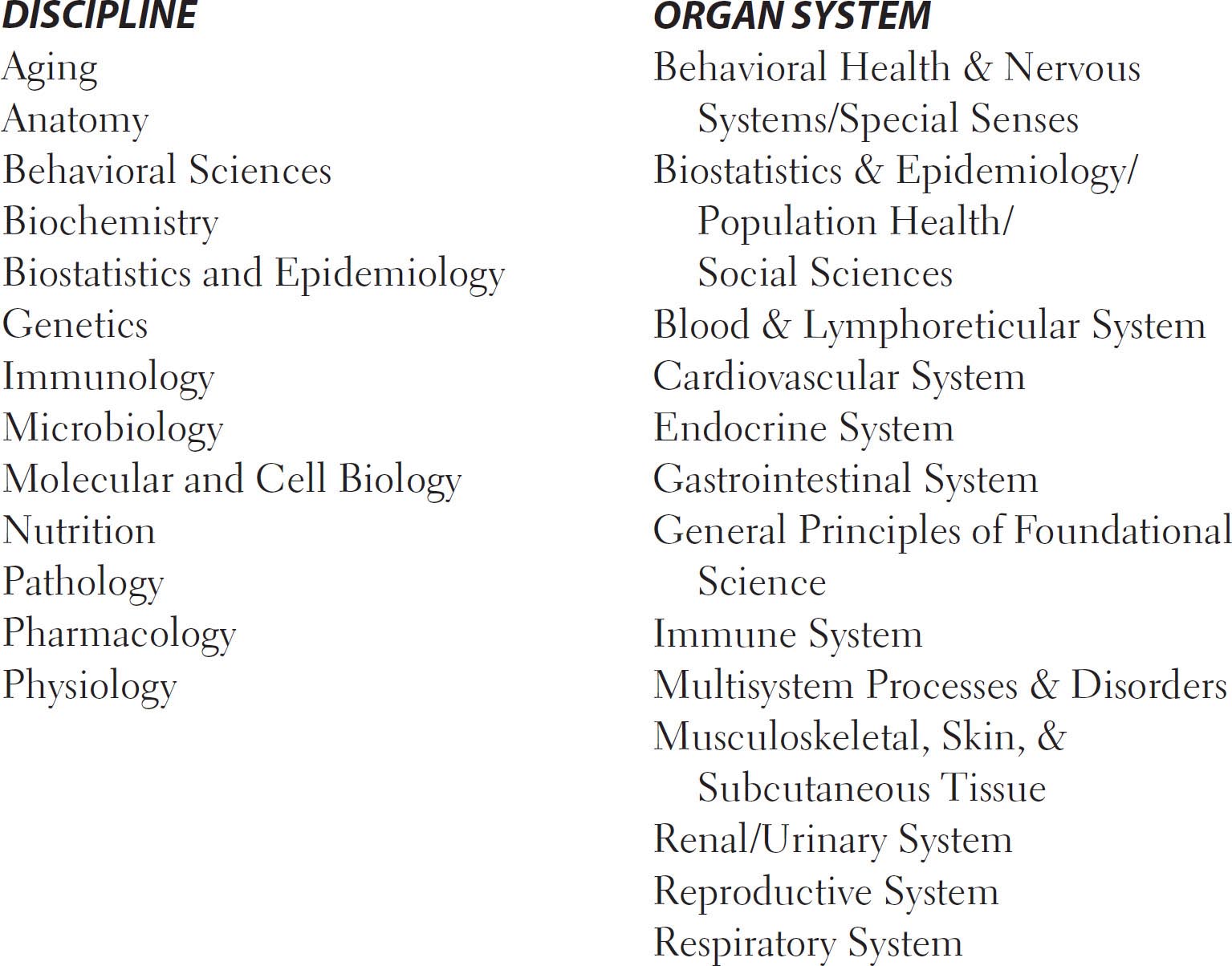

The Step 1 exam includes test items drawn from the following content areas1:

How Is the Computer-Based Test (CBT) Structured?

The CBT Step 1 exam consists of one “optional” tutorial/simulation block and seven “real” question blocks of up to 40 questions per block with no more than 280 questions in total, timed at 60 minutes per block. A short 11-question survey follows the last question block. The computer begins the survey with a prompt to proceed to the next block of questions.

Once an examinee finishes a particular question block on the CBT, he or she must click on a screen icon to continue to the next block. Examinees cannot go back and change their answers to questions from any previously completed block. However, changing answers is allowed within a block of questions as long as the block has not been ended and if time permits.

What Is the CBT Like?

Given the unique environment of the CBT, it’s important that you become familiar ahead of time with what your test-day conditions will be like. In fact, you can easily add up to 15 minutes to your break time! This is because the 15-minute tutorial offered on exam day may be skipped if you are already familiar with the exam procedures and the testing interface. The 15 minutes is then added to your allotted break time of 45 minutes for a total of 1 hour of potential break time. You can download the tutorial from the USMLE website and do it before test day. This tutorial interface is very similar to the one you will use in the exam; learn it now and you can skip taking it during the exam, giving you up to 15 extra minutes of break time. You can also gain experience with the CBT format by taking the 120 practice questions (3 blocks with 40 questions each) available online or by signing up for a practice session at a test center.

For security reasons, examinees are not allowed to bring any personal electronic equipment into the testing area. This includes both digital and analog watches, iPods, tablets, calculators, cell phones, and electronic paging devices. Examinees are also prohibited from carrying in their books, notes, pens/pencils, and scratch paper. Food and beverages are also prohibited in the testing area. The testing centers are monitored by audio and video surveillance equipment. However, most testing centers allot each examinee a small locker outside the testing area in which he or she can store snacks, beverages, and personal items.

Questions are typically presented in multiple choice format, with 4–5 possible answer options. There is a countdown timer on the lower left corner of the screen as well. There is also a button that allows the examinee to mark a question for review. If a given question happens to be longer than the screen (which occurs very rarely), a scroll bar will appear on the right, allowing the examinee to see the rest of the question. Regardless of whether the examinee clicks on an answer choice or leaves it blank, he or she must click the “Next” button to advance to the next question.

The USMLE features a small number of media clips in the form of audio and/or video. There may even be a question with a multimedia heart sound simulation. In these questions, a digital image of a torso appears on the screen, and the examinee directs a digital stethoscope to various auscultation points to listen for heart and breath sounds. The USMLE orientation materials include several practice questions in these formats. During the exam tutorial, examinees are given an opportunity to ensure that both the audio headphones and the volume are functioning properly. If you are already familiar with the tutorial and planning on skipping it, first skip ahead to the section where you can test your headphones. After you are sure the headphones are working properly, proceed to the exam.

The examinee can call up a window displaying normal laboratory values. In order to do so, he or she must click the “Lab” icon on the top part of the screen. Afterward, the examinee will have the option to choose between “Blood,” “Cerebrospinal,” “Hematologic,” or “Sweat and Urine.” The normal values screen may obscure the question if it is expanded. The examinee may have to scroll down to search for the needed lab values. You might want to memorize some common lab values so you spend less time on questions that require you to analyze these.

The CBT interface provides a running list of questions on the left part of the screen at all times. The software also permits examinees to highlight or cross out information by using their mouse. There is a “Notes” icon on the top part of the screen that allows students to write notes to themselves for review at a later time. Finally, the USMLE has recently added new functionality including text magnification and reverse color (white text on black background). Being familiar with these features can save time and may help you better view and organize the information you need to answer a question.

For those who feel they might benefit, the USMLE offers an opportunity to take a simulated test, or “CBT Practice Session” at a Prometric center. Students are eligible to register for this three-and-one-half-hour practice session after they have received their scheduling permit.

The same USMLE Step 1 sample test items (120 questions) available on the USMLE website, www.usmle.org, are used at these sessions. No new items will be presented. The practice session is available at a cost of $75 and is divided into a short tutorial and three 1-hour blocks of ~40 test items each. Students receive a printed percent-correct score after completing the session. No explanations of questions are provided.

You may register for a practice session online at www.usmle.org. A separate scheduling permit is issued for the practice session. Students should allow two weeks for receipt of this permit.

How Do I Register to Take the Exam?

Prometric test centers offer Step 1 on a year-round basis, except for the first two weeks in January and major holidays. The exam is given every day except Sunday at most centers. Some schools administer the exam on their own campuses. Check with the test center you want to use before making your exam plans.

US students can apply to take Step 1 at the NBME website. This application allows you to select one of 12 overlapping three-month blocks in which to be tested (eg, April–May–June, June–July–August). Choose your three-month eligibility period wisely. If you need to reschedule outside your initial three-month period, you can request a one-time extension of eligibility for the next contiguous three-month period, and pay a rescheduling fee. The application also includes a photo ID form that must be certified by an official at your medical school to verify your enrollment. After the NBME processes your application, it will send you a scheduling permit.

The scheduling permit you receive from the NBME will contain your USMLE identification number, the eligibility period in which you may take the exam, and two additional numbers. The first of these is known as your “scheduling number.” You must have this number in order to make your exam appointment with Prometric. The second number is known as the “candidate identification number,” or CIN. Examinees must enter their CINs at the Prometric workstation in order to access their exams. However, you will not be allowed to bring your permit into the exam and will be asked to copy your CIN onto your scratch paper. Prometric has no access to the codes. Do not lose your permit! You will not be allowed to take the exam unless you present this permit along with an unexpired, government-issued photo ID that includes your signature (such as a driver’s license or passport). Make sure the name on your photo ID exactly matches the name that appears on your scheduling permit.

Once you receive your scheduling permit, you may access the Prometric website or call Prometric’s toll-free number to arrange a time to take the exam. You may contact Prometric two weeks before the test date if you want to confirm identification requirements. Although requests for taking the exam may be completed more than six months before the test date, examinees will not receive their scheduling permits earlier than six months before the eligibility period. The eligibility period is the three-month period you have chosen to take the exam. Most medical students choose the April–June or June–August period. Because exams are scheduled on a “first-come, first-served” basis, it is recommended that you contact Prometric as soon as you receive your permit. After you’ve scheduled your exam, it’s a good idea to confirm your exam appointment with Prometric at least one week before your test date. Prometric will provide appointment confirmation on a print-out and by email. Be sure to read the 2018 USMLE Bulletin of Information for further details.

What If I Need to Reschedule the Exam?

You can change your test date and/or center by contacting Prometric at 1-800-MED-EXAM (1-800-633-3926) or www.prometric.com. Make sure to have your CIN when rescheduling. If you are rescheduling by phone, you must speak with a Prometric representative; leaving a voicemail message will not suffice. To avoid a rescheduling fee, you will need to request a change at least 31 calendar days before your appointment. Please note that your rescheduled test date must fall within your assigned three-month eligibility period.

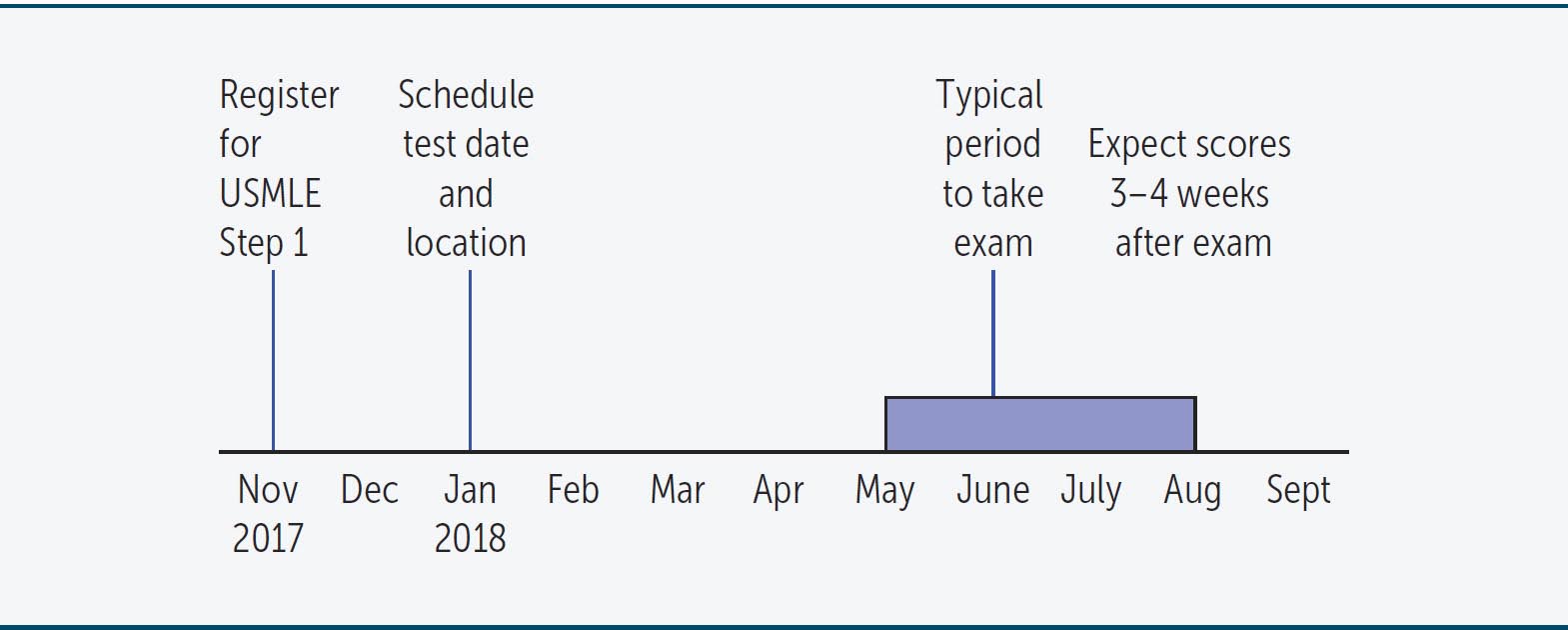

When Should I Register for the Exam?

You should plan to register as far in advance as possible ahead of your desired test date (eg, six months), but, depending on your particular test center, new dates and times may open closer to the date. Scheduling early will guarantee that you will get either your test center of choice or one within a 50-mile radius of your first choice. For most US medical students, the desired testing window is in June, since most medical school curricula for the second year end in May or June. Thus, US medical students should plan to register before January in anticipation of a June test date. The timing of the exam is more flexible for IMGs, as it is related only to when they finish exam preparation. Talk with upperclassmen who have already taken the test so you have real-life experience from students who went through a similar curriculum, then formulate your own strategy.

Where Can I Take the Exam?

Your testing location is arranged with Prometric when you call for your test date (after you receive your scheduling permit). For a list of Prometric locations nearest you, visit www.prometric.com.

How Long Will I Have to Wait Before I Get My Scores?

The USMLE reports scores in three to four weeks, unless there are delays in score processing. Examinees will be notified via email when their scores are available. By following the online instructions, examinees will be able to view, download, and print their score report online for ~120 days after score notification, after which scores can only be obtained through requesting an official USMLE transcript. Additional information about score timetables and accessibility is available on the official USMLE website.

What About Time?

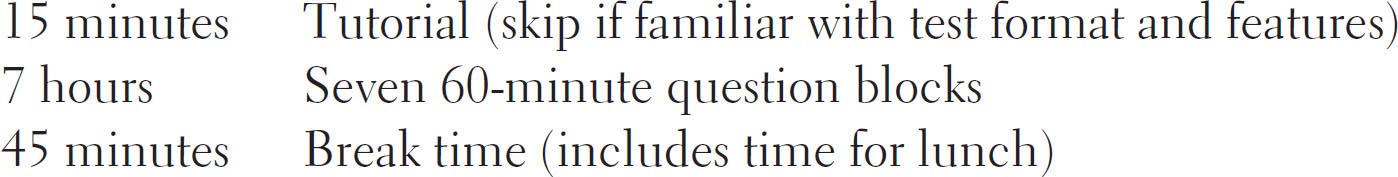

Time is of special interest on the CBT exam. Here’s a breakdown of the exam schedule:

The computer will keep track of how much time has elapsed on the exam. However, the computer will show you only how much time you have remaining in a given block. Therefore, it is up to you to determine if you are pacing yourself properly (at a rate of approximately one question per 90 seconds).

The computer does not warn you if you are spending more than your allotted time for a break. You should therefore budget your time so that you can take a short break when you need one and have time to eat. You must be especially careful not to spend too much time in between blocks (you should keep track of how much time elapses from the time you finish a block of questions to the time you start the next block). After you finish one question block, you’ll need to click to proceed to the next block of questions. If you do not click within 30 seconds, you will automatically be entered into a break period.

Break time for the day is 45 minutes, but you are not required to use all of it, nor are you required to use any of it. You can gain extra break time (but not extra time for the question blocks) by skipping the tutorial or by finishing a block ahead of the allotted time. Any time remaining on the clock when you finish a block gets added to your remaining break time. Once a new question block has been started, you may not take a break until you have reached the end of that block. If you do so, this will be recorded as an “unauthorized break” and will be reported on your final score report.

Finally, be aware that it may take a few minutes of your break time to “check out” of the secure resting room and then “check in” again to resume testing, so plan accordingly. The “check-in” process may include fingerprints, pocket checks, and metal detector scanning. Some students recommend pocketless clothing on exam day to streamline the process.

If I Freak Out and Leave, What Happens to My Score?

Your scheduling permit shows a CIN that you will need to enter to start your exam. Entering the CIN is the same as breaking the seal on a test book, and you are considered to have started the exam when you do so. However, no score will be reported if you do not complete the exam. In fact, if you leave at any time from the start of the test to the last block, no score will be reported. The fact that you started but did not complete the exam, however, will appear on your USMLE score transcript. Even though a score is not posted for incomplete tests, examinees may still get an option to request that their scores be calculated and reported if they desire; unanswered questions will be scored as incorrect.

The exam ends when all question blocks have been completed or when their time has expired. As you leave the testing center, you will receive a printed test-completion notice to document your completion of the exam. To receive an official score, you must finish the entire exam.

What Types of Questions Are Asked?

All questions on the exam are one-best-answer multiple choice items. Most questions consist of a clinical scenario or a direct question followed by a list of five or more options. You are required to select the single best answer among the options given. There are no “except,” “not,” or matching questions on the exam. A number of options may be partially correct, in which case you must select the option that best answers the question or completes the statement. Additionally, keep in mind that experimental questions may appear on the exam, which do not affect your score.

How Is the Test Scored?

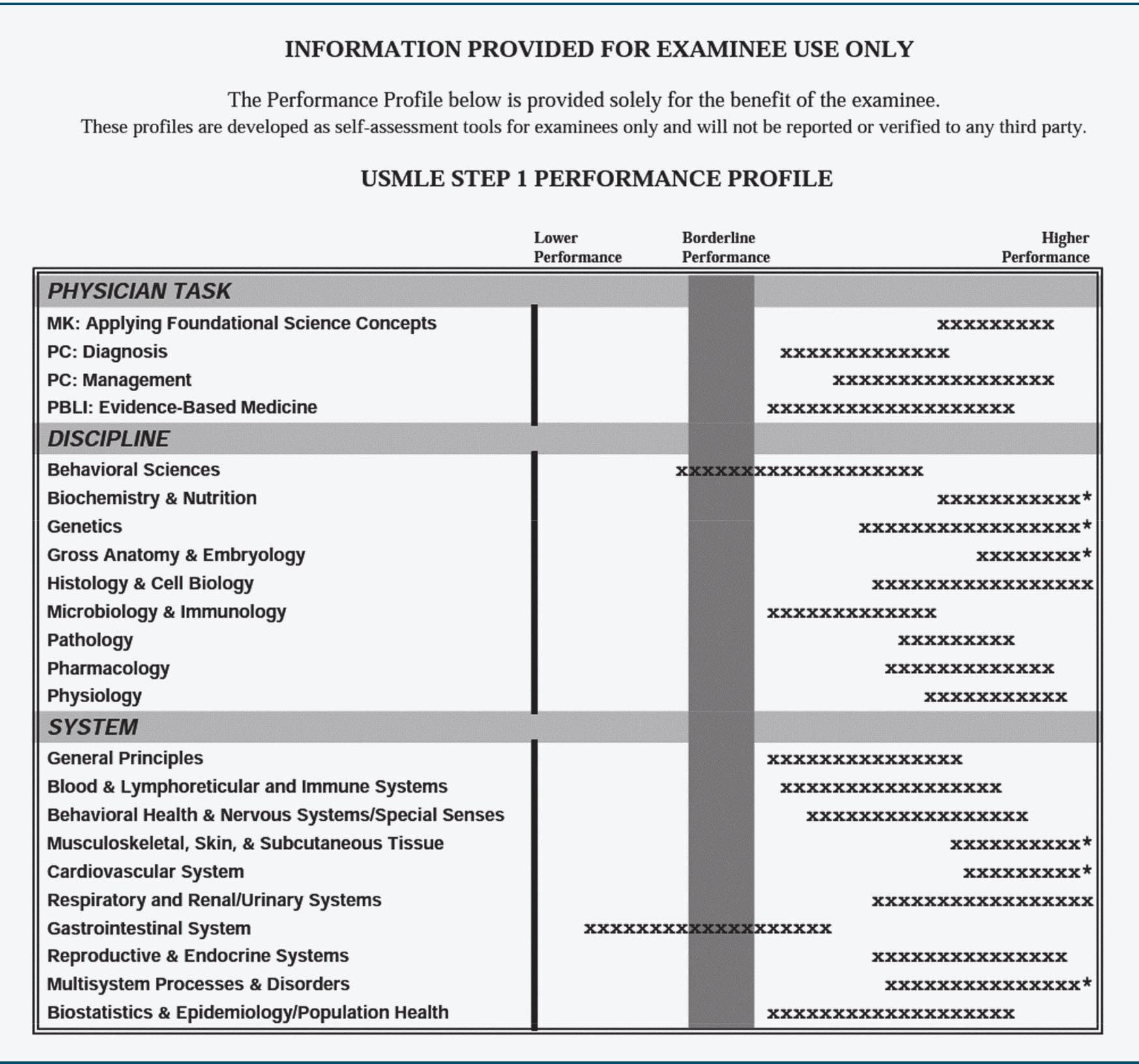

Each Step 1 examinee receives an electronic score report that includes the examinee’s pass/fail status, a three-digit test score, and a graphic depiction of the examinee’s performance by discipline and organ system or subject area. The actual organ system profiles reported may depend on the statistical characteristics of a given administration of the examination.

The USMLE score report is divided into two sections: performance by discipline and performance by organ system. Each of the questions (minus experimental questions) is tagged according to any or all relevant content areas. Your performance in each discipline and each organ system is represented by a line of X’s, where the width of the line is related to the confidence interval for your performance, which is often a direct consequence of the total number of questions for each discipline/system. If any lines have an asterisk (*) at the far right, this means your performance was exemplary in that area—not necessarily representing a perfect score, but often close to it (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Sample USMLE Step 1 Performance Profile.

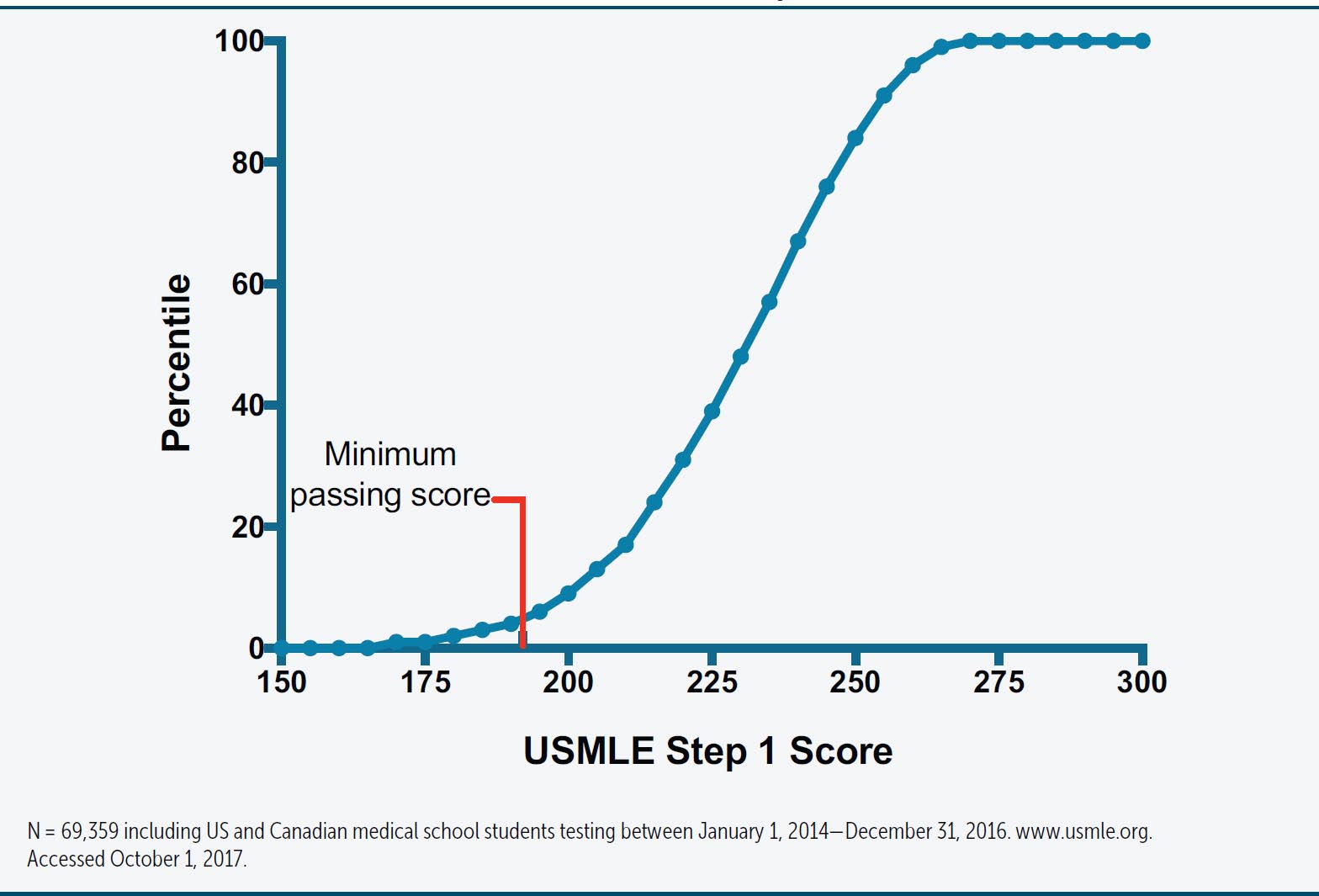

The NBME provides a three-digit test score based on the total number of items answered correctly on the examination, which corresponds to a particular percentile (see Figure 2). Your three-digit score will be qualified by the mean and standard deviation of US and Canadian medical school first-time examinees. The translation from the lines of X’s and number of asterisks you receive on your report to the three-digit score is unclear, but higher three-digit scores are associated with more asterisks.

FIGURE 2. Score and Percentile for First-time Step 1 Takers.

Since some questions may be experimental and are not counted, it is possible to get different scores for the same number of correct answers. In 2016, the mean score was 228 with a standard deviation of 21.

A score of 192 or higher is required to pass Step 1. The NBME does not report the minimum number of correct responses needed to pass, but estimates that it is roughly 60–70%. The NBME may adjust the minimum passing score in the future, so please check the USMLE website or www.firstaidteam.com for updates.

According to the USMLE, medical schools receive a listing of total scores and pass/fail results plus group summaries by discipline and organ system. Students can withhold their scores from their medical school if they wish. Official USMLE transcripts, which can be sent on request to residency programs, include only total scores, not performance profiles.

Consult the USMLE website or your medical school for the most current and accurate information regarding the examination.

What Does My Score Mean?

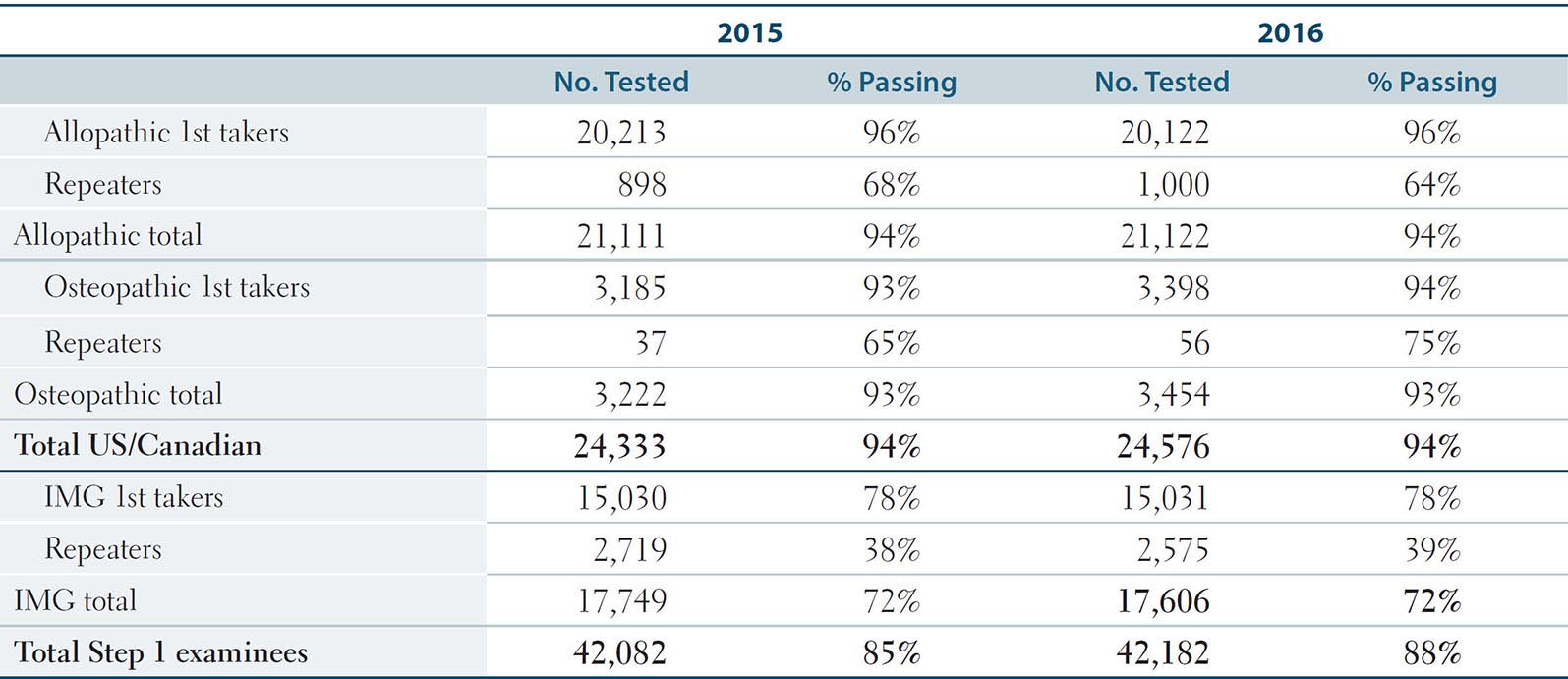

The most important point with the Step 1 score is passing versus failing. Passing essentially means, “Hey, you’re on your way to becoming a fully licensed doc.” As Table 1 shows, the majority of students pass the exam, so remember, we told you to relax.

TABLE 1. Passing Rates for the 2015—2016 USMLE Step 1.2

Beyond that, the main point of having a quantitative score is to give you a sense of how well you’ve done on the exam and to help schools and residencies rank their students and applicants, respectively.

Official NBME/USMLE Resources

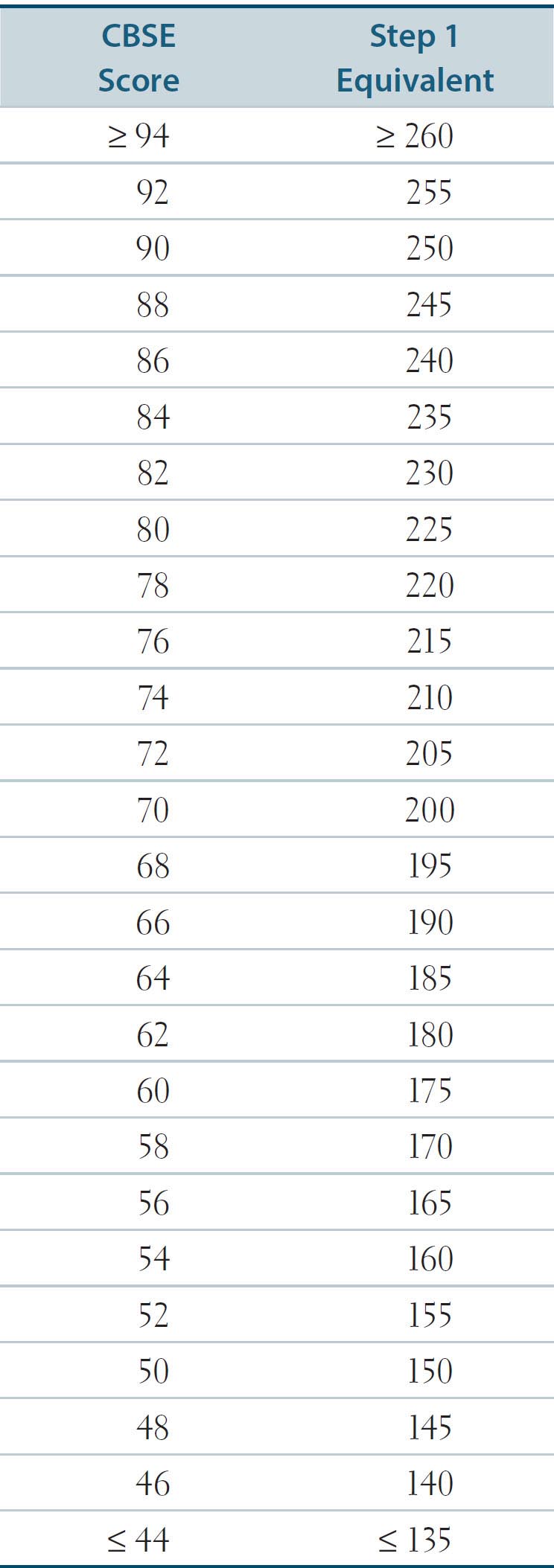

The NBME offers a Comprehensive Basic Science Examination (CBSE) for practice that is a shorter version of the Step 1. The CBSE contains four blocks of 50 questions each and covers material that is typically learned during the basic science years. Scores range from 45 to 95 and correlate with a Step 1 equivalent (see Table 2). The standard error of measurement is approximately 3 points, meaning a score of 80 would estimate the student’s proficiency is somewhere between 77 and 83. In other words, the actual Step 1 score could be predicted to be between 218 and 232. Of course, these values do not correlate exactly, and they do not reflect different test preparation methods. Many schools use this test to gauge whether a student is expected to pass Step 1. If this test is offered by your school, it is usually conducted at the end of regular didactic time before any dedicated Step 1 preparation. If you do not encounter the CBSE before your dedicated study time, you need not worry about taking it. Use the information to help set realistic goals and timetables for your success.

TABLE 2. CBSE to USMLE Score Prediction.

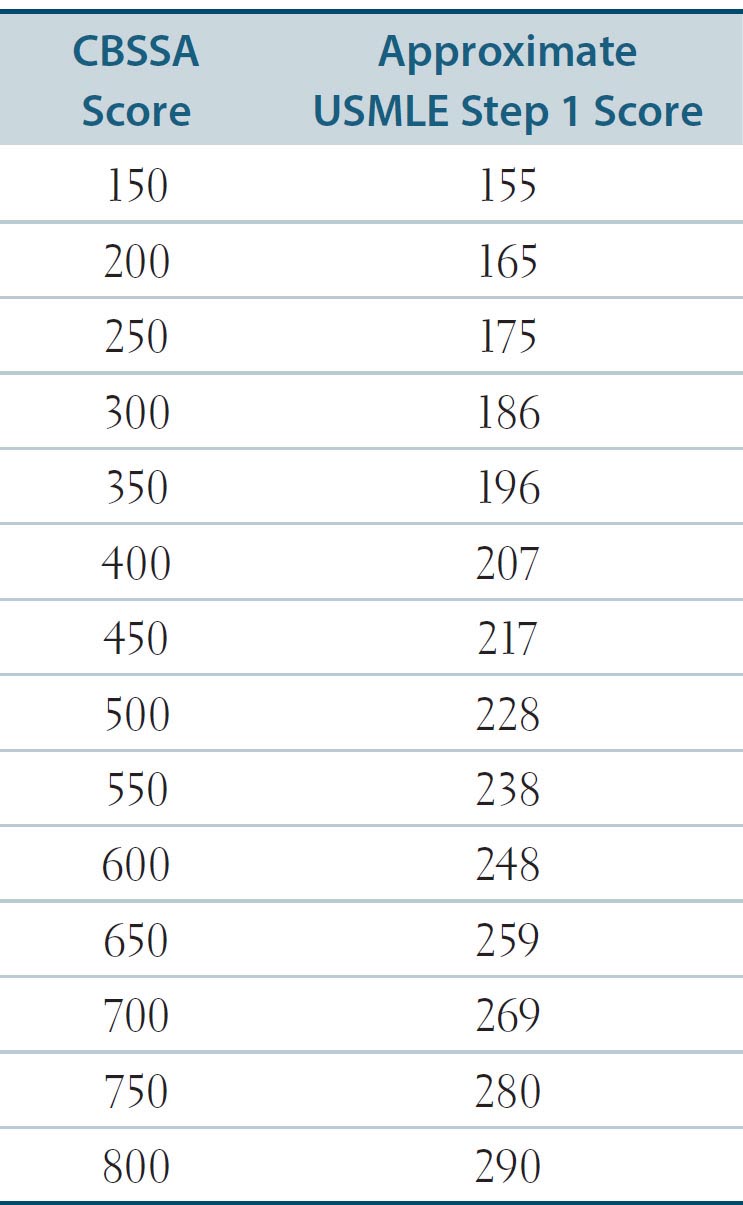

The NBME also offers six forms of Comprehensive Basic Science Self-Assessment (CBSSA). Students who prepared for the exam using this web-based tool reported that they found the format and content highly indicative of questions tested on the actual exam. In addition, the CBSSA is a fair predictor of USMLE performance (see Table 3). The test interface, however, does not match the actual USMLE test interface, so practicing with these forms alone is not advised.

TABLE 3. CBSSA to USMLE Score Prediction.

The CBSSA exists in two formats: standard-paced and self-paced, both of which consist of four sections of 50 questions each (for a total of 200 multiple choice items). The standard-paced format allows the user up to 65 minutes to complete each section, reflecting time limits similar to the actual exam. By contrast, the self-paced format places a 4:20 time limit on answering all multiple choice questions. Every few years, a new form is released and an older one is retired, reflecting changes in exam content. Therefore, the newer exams tend to be more similar to the actual Step 1, and scores from these exams tend to provide a better estimation of exam day performance.

Keep in mind that this bank of questions is available only on the web. The NBME requires that users log on, register, and start the test within 30 days of registration. Once the assessment has begun, users are required to complete the sections within 20 days. Following completion of the questions, the CBSSA provides a performance profile indicating the user’s relative strengths and weaknesses, much like the report profile for the USMLE Step 1 exam. The profile is scaled with an average score of 500 and a standard deviation of 100. In addition to the performance profile, examinees will be informed of the number of questions answered incorrectly. You will have the ability to review the text of the incorrect question with the correct answer. Explanations for the correct answer, however, will not be provided. The NBME charges $60 for assessments with expanded feedback. The fees are payable by credit card or money order. For more information regarding the CBSE and the CBSSA, visit the NBME’s website at www.nbme.org.

The NBME scoring system is weighted for each assessment exam. While some exams seem more difficult than others, the score reported takes into account these inter-test differences when predicting Step 1 performance. Also, while many students report seeing Step 1 questions “word-for-word” out of the assessments, the NBME makes special note that no live USMLE questions are shown on any NBME assessment.

Lastly, the International Foundations of Medicine (IFOM) offers a Basic Science Examination (BSE) practice exam at participating Prometric test centers for $200. Students may also take the self-assessment test online for $35 through the NBME’s website. The IFOM BSE is intended to determine an examinee’s relative areas of strength and weakness in general areas of basic science—not to predict performance on the USMLE Step 1 exam—and the content covered by the two examinations is somewhat different. However, because there is substantial overlap in content coverage and many IFOM items were previously used on the USMLE Step 1, it is possible to roughly project IFOM performance onto the USMLE Step 1 score scale. More information is available at http://www.nbme.org/ifom/.

DEFINING YOUR GOAL

DEFINING YOUR GOAL

It is useful to define your own personal performance goal when approaching the USMLE Step 1. Your style and intensity of preparation can then be matched to your goal. Furthermore, your goal may depend on your school’s requirements, your specialty choice, your grades to date, and your personal assessment of the test’s importance. Do your best to define your goals early so that you can prepare accordingly.

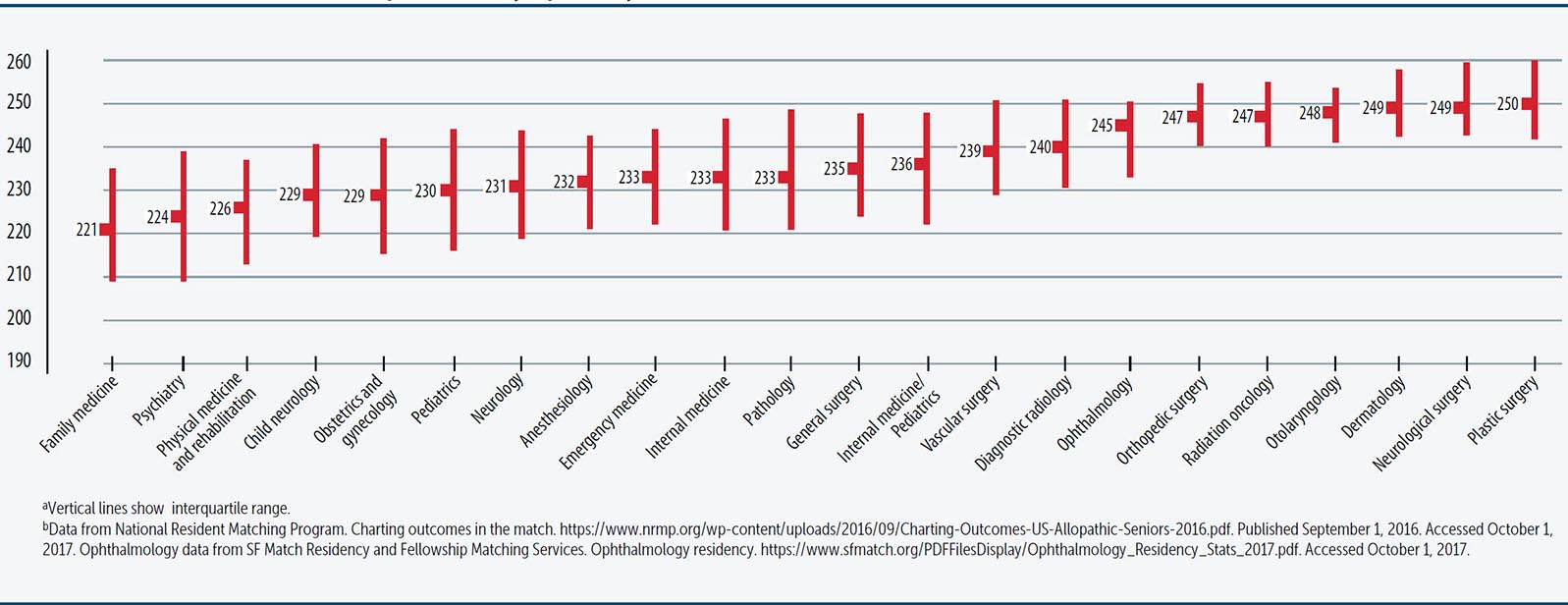

The value of the USMLE Step 1 score in selecting residency applicants remains controversial, and some have called for less emphasis to be placed on the score when selecting or screening applicants.3 For the time being, however, it continues to be an important part of the residency application, and it is not uncommon for some specialties to implement filters that screen out applicants who score below a certain cutoff. This is more likely to be seen in competitive specialties (eg, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, dermatology, otolaryngology). Independent of your career goals, you can maximize your future options by doing your best to obtain the highest score possible (see Figure 3). At the same time, your Step 1 score is only one of a number of factors that are assessed when you apply for residency. In fact, many residency programs value other criteria such as letters of recommendation, third-year clerkship grades, honors, and research experience more than a high score on Step 1. Fourth-year medical students who have recently completed the residency application process can be a valuable resource in this regard.

FIGURE 3. Median USMLE Step 1 Score by Specialty for Matched US Seniors.a,b

LEARNING STRATEGIES

LEARNING STRATEGIES

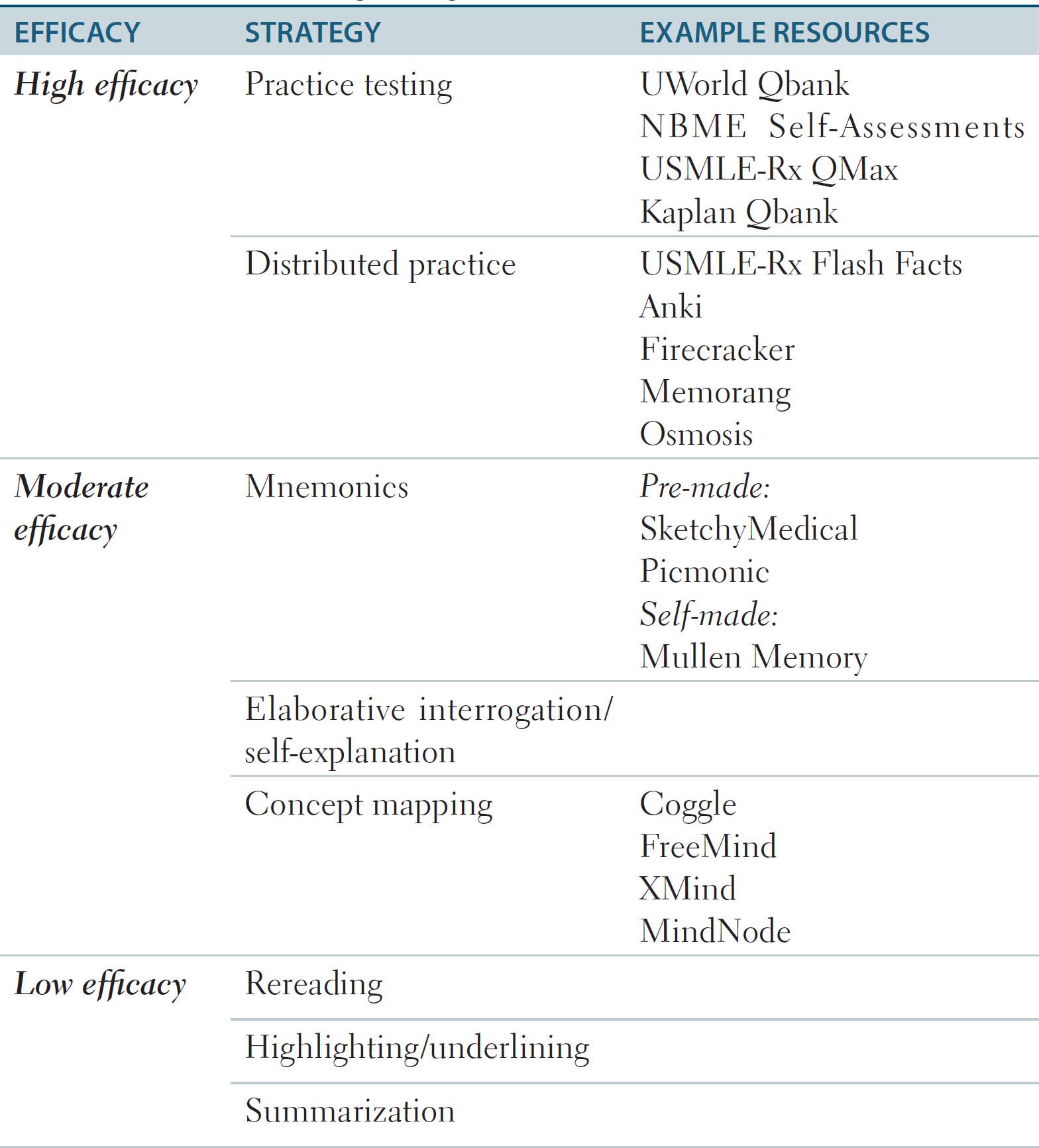

Many students feel overwhelmed during the preclinical years and struggle to find an effective learning strategy. Table 4 lists several learning strategies you can try and their estimated effectiveness for Step 1 preparation based on the literature (see References). These are merely suggestions, and it’s important to take your learning preferences into account. Your comprehensive learning approach will contain a combination of strategies (eg, elaborative interrogation followed by practice testing, mnemonics review using spaced repetition, etc). Regardless of your choice, the foundation of knowledge you build during your basic science years is the most important resource for success on the USMLE Step 1.

TABLE 4. Effective Learning Strategies.

HIGH EFFICACY

Practice Testing

Also called “retrieval practice,” practice testing has both direct and indirect benefits to the learner.4 Effortful retrieval of answers does not only identify weak spots—it directly strengthens long-term retention of material.5 The more effortful the recall, the better the long-term retention. This advantage has been shown to result in higher test scores and GPAs.6 In fact, research has shown a positive correlation between the number of boards-style practice questions completed and Step 1 scores among medical students.7

Practice testing should be done with “interleaving” (mixing of questions from different topics in a single session). Question banks often allow you to intermingle topics. Interleaved practice helps learners develop their ability to focus on the relevant concept when faced with many possibilities. Practicing topics in massed fashion (eg, all cardiology, then all dermatology) may seem intuitive, but there is strong evidence that interleaving correlates with longer-term retention and increased student achievement, especially on tasks that involve problem solving.5

In addition to using question banks, you can test yourself by arranging your notes in a question-answer format (eg, via flash cards). Testing these Q&As in random order allows you to reap the benefit of interleaved practice. Bear in mind that the utility of practice testing comes from the practice of information retrieval, so simply reading through Q&As will attenuate this benefit.

Distributed Practice

Also called “spaced repetition,” distributed practice is the opposite of massed practice or “cramming.” Learners review material at increasingly spaced out intervals (days to weeks to months). Massed learning may produce more short-term gains and satisfaction, but learners who use distributed practice have better mastery and retention over the long term.5,9

Flash cards are a simple way to incorporate both distributed practice and practice testing. Studies have linked spaced repetition learning with flash cards to improved long-term knowledge retention and higher exam scores.6,8,10 Apps with automated spaced-repetition software (SRS) for flash cards exist for smartphones and tablets, so the cards are accessible anywhere. Proceed with caution: there is an art to making and reviewing cards. The ease of quickly downloading or creating digital cards can lead to flash card overload (it is unsustainable to make 50 flash cards per lecture!). Even at a modest pace, the thousands upon thousands of cards are too overwhelming for Step 1 preparation. Unless you have specific high-yield cards (and have checked the content with high-yield resources), stick to pre-made cards by reputable sources that curate the vast amount of knowledge for you.

If you prefer pen and paper, consider using a planner or spreadsheet to organize your study material over time. Distributed practice allows for some forgetting of information, and the added effort of recall over time strengthens the learning.

MODERATE EFFICACY

Mnemonics

A “mnemonic” refers to any device that assists memory, such as acronyms, mental imagery (eg, keywords with or without memory palaces), etc. Keyword mnemonics have been shown to produce superior knowledge retention when compared with rote memorization in many scenarios. However, they are generally more effective when applied to memorization-heavy, keyword-friendly topics and may not be broadly suitable.5 Keyword mnemonics may not produce long-term retention, so consider combining mnemonics with distributed, retrieval-based practice (eg, via flash cards with SRS).

Self-made mnemonics may have an advantage when material is simple and keyword friendly. If you can create your own mnemonic that accurately represents the material, this will be more memorable. When topics are complex and accurate mnemonics are challenging to create, pre-made mnemonics may be more effective, especially if you are inexperienced at creating mnemonics.11

Elaborative Interrogation/Self-Explanation

Elaborative interrogation (“why” questions) and self-explanation (general questioning) prompt learners to generate explanations for facts. When reading passages of discrete facts, consider using these techniques, which have been shown to be more effective than rereading (eg, improved recall and better problem-solving/diagnostic performance).5,12,13

Concept Mapping

Concept mapping is a method for graphically organizing knowledge, with concepts enclosed in boxes and lines drawn between related concepts. Creating or studying concept maps may be more effective than other activities (eg, writing or reading summaries/outlines). However, studies have reached mixed conclusions about its utility, and the small size of this effect raises doubts about its authenticity and pedagogic significance.14

LOW EFFICACY

Rereading

While the most commonly used method among surveyed students, rereading has not been shown to correlate with grade point average.9 Due to its popularity, rereading is often a comparator in studies on learning. Other strategies that we have discussed (eg, practice testing) have been shown to be significantly more effective than rereading.

Highlighting/Underlining

Because this method is passive, it tends to be of minimal value for learning and recall. In fact, lower-performing students are more likely to use these techniques.9 Students who highlight and underline do not learn how to actively recall learned information and thus find it difficult to apply knowledge to exam questions.

Summarization

While more useful for improving performance on generative measures (eg, free recall or essays), summarization is less useful for exams that depend on recognition (eg, multiple choice). Findings on the overall efficacy of this method have been mixed.5

TIMELINE FOR STUDY

TIMELINE FOR STUDY

Before Starting

Your preparation for the USMLE Step 1 should begin when you enter medical school. Organize and commit to studying from the beginning so that when the time comes to prepare for the USMLE, you will be ready with a strong foundation.

Make a Schedule

After you have defined your goals, map out a study schedule that is consistent with your objectives, your vacation time, the difficulty of your ongoing coursework, and your family and social commitments (see Figure 4). Determine whether you want to spread out your study time or concentrate it into 14-hour study days in the final weeks. Then factor in your own history in preparing for standardized examinations (eg, SAT, MCAT). Talk to students at your school who have recently taken Step 1. Ask them for their study schedules, especially those who have study habits and goals similar to yours.

FIGURE 4 . Typical Timeline for the USMLE Step 1.

Typically, US medical schools allot between four and eight weeks for dedicated Step 1 preparation. The time you dedicate to exam preparation will depend on your target score as well as your success in preparing yourself during the first two years of medical school. Some students reserve about a week at the end of their study period for final review; others save just a few days. When you have scheduled your exam date, do your best to adhere to it. Studies show that a later testing date does not translate into a higher score, so avoid pushing back your test date without good reason.15

Make your schedule realistic, and set achievable goals. Many students make the mistake of studying at a level of detail that requires too much time for a comprehensive review—reading Gray’s Anatomy in a couple of days is not a realistic goal! Have one catch-up day per week of studying. No matter how well you stick to your schedule, unexpected events happen. But don’t let yourself procrastinate because you have catch-up days; stick to your schedule as closely as possible and revise it regularly on the basis of your actual progress. Be careful not to lose focus. Beware of feelings of inadequacy when comparing study schedules and progress with your peers. Avoid others who stress you out. Focus on a few top-rated resources that suit your learning style—not on some obscure books your friends may pass down to you. Accept the fact that you cannot learn it all.

You will need time for uninterrupted and focused study. Plan your personal affairs to minimize crisis situations near the date of the test. Allot an adequate number of breaks in your study schedule to avoid burnout. Maintain a healthy lifestyle with proper diet, exercise, and sleep.

Another important aspect of your preparation is your studying environment. Study where you have always been comfortable studying. Be sure to include everything you need close by (review books, notes, coffee, snacks, etc). If you’re the kind of person who cannot study alone, form a study group with other students taking the exam. The main point here is to create a comfortable environment with minimal distractions.

Year(s) Prior

The knowledge you gained during your first two years of medical school and even during your undergraduate years should provide the groundwork on which to base your test preparation. Student scores on NBME subject tests (commonly known as “shelf exams”) have been shown to be highly correlated with subsequent Step 1 scores.16 Moreover, undergraduate science GPAs as well as MCAT scores are strong predictors of performance on the Step 1 exam.17

We also recommend that you buy highly rated review books early in your first year of medical school and use them as you study throughout the two years. When Step 1 comes along, these books will be familiar and personalized to the way in which you learn. It is risky and intimidating to use unfamiliar review books in the final two or three weeks preceding the exam. Some students find it helpful to personalize and annotate First Aid throughout the curriculum.

Months Prior

Review test dates and the application procedure. Testing for the USMLE Step 1 is done on a year-round basis. If you have disabilities or special circumstances, contact the NBME as early as possible to discuss test accommodations (see the Section I Supplement at www.firstaidteam.com/bonus).

Use this time to finalize your ideal schedule. Consider upcoming breaks and whether you want to relax or study. Work backward from your test date to make sure you finish at least one question bank. Also add time to redo missed or flagged questions (which may be half the bank). This is the time to build a structured plan with enough flexibility for the realities of life.

Begin doing blocks of questions from reputable question banks under “real” conditions. Don’t use tutor mode until you’re sure you can finish blocks in the allotted time. It is important to continue balancing success in your normal studies with the Step 1 test preparation process.

Weeks Prior (Dedicated Preparation)

Your dedicated prep time may be one week or two months. You should have a working plan as you go into this period. Finish your schoolwork strong, take a day off, and then get to work. Start by simulating a full-length USMLE Step 1 if you haven’t yet done so. Consider doing one NBME CBSSA and the free questions from the NBME website. Alternatively, you could choose 7 blocks of randomized questions from a commercial question bank. Make sure you get feedback on your strengths and weaknesses and adjust your studying accordingly. Many students study from review sources or comprehensive programs for part of the day, then do question blocks. Also, keep in mind that reviewing a question block can take upward of two hours. Feedback from CBSSA exams and question banks will help you focus on your weaknesses.

One Week Prior

Make sure you have your CIN (found on your scheduling permit) as well as other items necessary for the day of the examination, including a current driver’s license or another form of photo ID with your signature (make sure the name on your ID exactly matches that on your scheduling permit). Confirm the Prometric testing center location and test time. Work out how you will get to the testing center and what parking and traffic problems you might encounter. Drive separately from other students taking the test on the same day, and exchange cell phone numbers in case of emergencies. If possible, visit the testing site to get a better idea of the testing conditions you will face. Determine what you will do for lunch. Make sure you have everything you need to ensure that you will be comfortable and alert at the test site. It may be beneficial to adjust your schedule to start waking up at the same time that you will on your test day. And of course, make sure to maintain a healthy lifestyle and get enough sleep.

One Day Prior

Try your best to relax and rest the night before the test. Double-check your admissions and test-taking materials as well as the comfort measures discussed earlier so that you will not have to deal with such details on the morning of the exam. At this point it will be more effective to review short-term memory material that you’re already familiar with than to try to learn new material. The Rapid Review section at the end of this book is high yield for last-minute studying. Remember that regardless of how hard you have studied, you cannot know everything. There will be things on the exam that you have never even seen before, so do not panic. Do not underestimate your abilities.

Many students report difficulty sleeping the night prior to the exam. This is often exacerbated by going to bed much earlier than usual. Do whatever it takes to ensure a good night’s sleep (eg, massage, exercise, warm milk, no back-lit screens at night). Do not change your daily routine prior to the exam. Exam day is not the day for a caffeine-withdrawal headache.

Morning of the Exam

On the morning of the Step 1 exam, wake up at your regular time and eat a normal breakfast. If you think it will help you, have a close friend or family member check to make sure you get out of bed. Make sure you have your scheduling permit admission ticket, test-taking materials, and comfort measures as discussed earlier. Wear loose, comfortable clothing. Plan for a variable temperature in the testing center. Arrive at the test site 30 minutes before the time designated on the admission ticket; however, do not come too early, as doing so may intensify your anxiety. When you arrive at the test site, the proctor should give you a USMLE information sheet that will explain critical factors such as the proper use of break time. Seating may be assigned, but ask to be reseated if necessary; you need to be seated in an area that will allow you to remain comfortable and to concentrate. Get to know your testing station, especially if you have never been in a Prometric testing center before. Listen to your proctors regarding any changes in instructions or testing procedures that may apply to your test site.

Finally, remember that it is natural (and even beneficial) to be a little nervous. Focus on being mentally clear and alert. Avoid panic. When you are asked to begin the exam, take a deep breath, focus on the screen, and then begin. Keep an eye on the timer. Take advantage of breaks between blocks to stretch, maybe do some jumping jacks, and relax for a moment with deep breathing or stretching.

After the Test

After you have completed the exam, be sure to have fun and relax regardless of how you may feel. Taking the test is an achievement in itself. Remember, you are much more likely to have passed than not. Enjoy the free time you have before your clerkships. Expect to experience some “reentry” phenomena as you try to regain a real life. Once you have recovered sufficiently from the test (or from partying), we invite you to send us your feedback, corrections, and suggestions for entries, facts, mnemonics, strategies, resource ratings, and the like (see p. xvii, How to Contribute). Sharing your experience will benefit fellow medical students and IMGs.

STUDY MATERIALS

STUDY MATERIALS

Quality Considerations

Although an ever-increasing number of review books and software are now available on the market, the quality of such material is highly variable. Some common problems are as follows:

Certain review books are too detailed to allow for review in a reasonable amount of time or cover subtopics that are not emphasized on the exam.

Certain review books are too detailed to allow for review in a reasonable amount of time or cover subtopics that are not emphasized on the exam.

Many sample question books were originally written years ago and have not been adequately updated to reflect recent trends.

Many sample question books were originally written years ago and have not been adequately updated to reflect recent trends.

Some question banks test to a level of detail that you will not find on the exam.

Some question banks test to a level of detail that you will not find on the exam.

Review Books

In selecting review books, be sure to weigh different opinions against each other, read the reviews and ratings in Section IV of this guide, examine the books closely in the bookstore, and choose carefully. You are investing not only money but also your limited study time. Do not worry about finding the “perfect” book, as many subjects simply do not have one, and different students prefer different formats. Supplement your chosen books with personal notes from other sources, including what you learn from question banks.

There are two types of review books: those that are stand-alone titles and those that are part of a series. Books in a series generally have the same style, and you must decide if that style works for you. However, a given style is not optimal for every subject.

You should also find out which books are up to date. Some recent editions reflect major improvements, whereas others contain only cursory changes. Take into consideration how a book reflects the format of the USMLE Step 1.

Apps

With the explosion of smartphones and tablets, apps are an increasingly popular way to review for the Step 1 exam. The majority of apps are compatible with both iOS and Android. Many popular Step 1 review resources (eg, UWorld, USMLE-Rx) have apps that are compatible with their software. Many popular web references (eg, UpToDate) also now offer app versions. All of these apps offer flexibility, allowing you to study while away from a computer (eg, while traveling).

Practice Tests

Taking practice tests provides valuable information about potential strengths and weaknesses in your fund of knowledge and test-taking skills. Some students use practice examinations simply as a means of breaking up the monotony of studying and adding variety to their study schedule, whereas other students rely almost solely on practice. You should also subscribe to one or more high-quality question banks. In addition, students report that many current practice-exam books have questions that are, on average, shorter and less clinically oriented than those on the current USMLE Step 1.

Additionally, some students preparing for the Step 1 exam have started to incorporate case-based books intended primarily for clinical students on the wards or studying for the Step 2 CK exam. First Aid Cases for the USMLE Step 1 aims to directly address this need.

After taking a practice test, spend time on each question and each answer choice whether you were right or wrong. There are important teaching points in each explanation. Knowing why a wrong answer choice is incorrect is just as important as knowing why the right answer is correct. Do not panic if your practice scores are low as many questions try to trick or distract you to highlight a certain point. Use the questions you missed or were unsure about to develop focused plans during your scheduled catch-up time.

Textbooks and Course Syllabi

Limit your use of textbooks and course syllabi for Step 1 review. Many textbooks are too detailed for high-yield review and include material that is generally not tested on the USMLE Step 1 (eg, drug dosages, complex chemical structures). Syllabi, although familiar, are inconsistent across medical schools and frequently reflect the emphasis of individual faculty, which often does not correspond to that of the USMLE Step 1. Syllabi also tend to be less organized than top-rated books and generally contain fewer diagrams and study questions.

TEST-TAKING STRATEGIES

TEST-TAKING STRATEGIES

Your test performance will be influenced by both your knowledge and your test-taking skills. You can strengthen your performance by considering each of these factors. Test-taking skills and strategies should be developed and perfected well in advance of the test date so that you can concentrate on the test itself. We suggest that you try the following strategies to see if they might work for you.

Pacing

You have seven hours to complete up to 280 questions. Note that each one-hour block contains up to 40 questions. This works out to approximately 90 seconds per question. We recommend following the “1 minute rule” to pace yourself. Spend no more than 1 minute on each question. If you are still unsure about the answer after this time, mark the question, make an educated guess, and move on. Following this rule, you should have approximately 20 minutes left after all questions are answered, which you can use to revisit all of your marked questions. Remember that some questions may be experimental and do not count for points (and reassure yourself that these experimental questions are the ones that are stumping you). In the past, pacing errors have been detrimental to the performance of even highly prepared examinees. The bottom line is to keep one eye on the clock at all times!

Dealing with Each Question

There are several established techniques for efficiently approaching multiple choice questions; find what works for you. One technique begins with identifying each question as easy, workable, or impossible. Your goal should be to answer all easy questions, resolve all workable questions in a reasonable amount of time, and make quick and intelligent guesses on all impossible questions. Most students read the stem, think of the answer, and turn immediately to the choices. A second technique is to first skim the answer choices to get a context, then read the last sentence of the question (the lead-in), and then read through the passage quickly, extracting only information relevant to answering the question. This can be particularly helpful for questions with long clinical vignettes. Try a variety of techniques on practice exams and see what works best for you. If you get overwhelmed, remember that a 30-second time out to refocus may get you back on track.

Guessing

There is no penalty for wrong answers. Thus, no test block should be left with unanswered questions. A hunch is probably better than a random guess. If you have to guess, we suggest selecting an answer you recognize over one with which you are totally unfamiliar.

Changing Your Answer

The conventional wisdom is not to change answers that you have already marked unless there is a convincing and logical reason to do so—in other words, go with your “first hunch.” Many question banks tell you how many questions you changed from right to wrong, wrong to wrong, and wrong to right. Use this feedback to judge how good a second-guesser you are. If you have extra time, reread the question stem and make sure you didn’t misinterpret the question.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE STRATEGIES

CLINICAL VIGNETTE STRATEGIES

In recent years, the USMLE Step 1 has become increasingly clinically oriented. This change mirrors the trend in medical education toward introducing students to clinical problem solving during the basic science years. The increasing clinical emphasis on Step 1 may be challenging to those students who attend schools with a more traditional curriculum.

What Is a Clinical Vignette?

A clinical vignette is a short (usually paragraph-long) description of a patient, including demographics, presenting symptoms, signs, and other information concerning the patient. Sometimes this paragraph is followed by a brief listing of important physical findings and/or laboratory results. The task of assimilating all this information and answering the associated question in the span of one minute can be intimidating. So be prepared to read quickly and think on your feet. Remember that the question is often indirectly asking something you already know.

Strategy

Remember that Step 1 vignettes usually describe diseases or disorders in their most classic presentation. So look for cardinal signs (eg, malar rash for SLE or nuchal rigidity for meningitis) in the narrative history. Be aware that the question will contain classic signs and symptoms instead of buzzwords. Sometimes the data from labs and the physical exam will help you confirm or reject possible diagnoses, thereby helping you rule answer choices in or out. In some cases, they will be a dead giveaway for the diagnosis.

Making a diagnosis from the history and data is often not the final answer. Not infrequently, the diagnosis is divulged at the end of the vignette, after you have just struggled through the narrative to come up with a diagnosis of your own. The question might then ask about a related aspect of the diagnosed disease. Consider skimming the answer choices and lead-in before diving into a long stem. However, be careful with skimming the answer choices; going too fast may warp your perception of what the vignette is asking.

IF YOU THINK YOU FAILED

IF YOU THINK YOU FAILED

After the test, many examinees feel that they have failed, and most are at the very least unsure of their pass/fail status. There are several sensible steps you can take to plan for the future in the event that you do not achieve a passing score. First, save and organize all your study materials, including review books, practice tests, and notes. Familiarize yourself with the reapplication procedures for Step 1, including application deadlines and upcoming test dates.

Make sure you know both your school’s and the NBME’s policies regarding retakes. The NBME allows a maximum of six attempts to pass each Step examination.18 You may take Step 1 no more than three times within a 12-month period. Your fourth and subsequent attempts must be at least 12 months after your first attempt at that exam and at least six months after your most recent attempt at that exam.

The performance profiles on the back of the USMLE Step 1 score report provide valuable feedback concerning your relative strengths and weaknesses. Study these profiles closely. Set up a study timeline to strengthen gaps in your knowledge as well as to maintain and improve what you already know. Do not neglect high-yield subjects. It is normal to feel somewhat anxious about retaking the test, but if anxiety becomes a problem, seek appropriate counseling.

TESTING AGENCIES

TESTING AGENCIES

National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) / USMLE Secretariat

National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) / USMLE Secretariat

Department of Licensing Examination Services

3750 Market Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104-3102

(215) 590-9500 (operator) or

(215) 590-9700 (automated information line)

Fax: (215) 590-9457

Email: webmail@nbme.org

www.nbme.org

Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG)

Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG)

3624 Market Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104-2685

(215) 386-5900

Fax: (215) 386-9196

Email: info@ecfmg.org

www.ecfmg.org

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

1. United States Medical Licensing Examination. Available from: http://www.usmle.org/bulletin/exam-content. Accessed September 25, 2017.

2. United States Medical Licensing Examination. 2016 Performance Data. Available from: http://www.usmle.org/performance-data/default.aspx#2015_step-1. Accessed September 25, 2017.

3. Prober CG, Kolars JC, First LR, et al. A plea to reassess the role of United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 scores in residency selection. Acad Med. 2016;91(1):12–15.

4. Roediger HL, Butler AC. The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(1):20–27.

5. Dunlosky J, Rawson KA, Marsh EJ, et al. Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychol Sci Publ Int. 2013;14(1):4–58.

6. Larsen DP, Butler AC, Lawson AL, et al. The importance of seeing the patient: test-enhanced learning with standardized patients and written tests improves clinical application of knowledge. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2013;18(3):409–425.

7. Panus PC, Stewart DW, Hagemeier NE, et al. A subgroup analysis of the impact of self-testing frequency on examination scores in a pathophysiology course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(9):165.

8. Deng F, Gluckstein JA, Larsen DP. Student-directed retrieval practice is a predictor of medical licensing examination performance. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(6):308–313.

9. McAndrew M, Morrow CS, Atiyeh L, et al. Dental student study strategies: are self-testing and scheduling related to academic performance? J Dent Educ. 2016;80(5):542–552.

10. Augustin M. How to learn effectively in medical school: test yourself, learn actively, and repeat in intervals. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87(2):207–212.

11. Bellezza FS. Mnemonic devices: classification, characteristics, and criteria. Rev Educ Res. 1981;51(2):247–275.

12. Dyer J-O, Hudon A, Montpetit-Tourangeau K, et al. Example-based learning: comparing the effects of additionally providing three different integrative learning activities on physiotherapy intervention knowledge. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:37.

13. Chamberland M, Mamede S, St-Onge C, et al. Self-explanation in learning clinical reasoning: the added value of examples and prompts. Med Educ. 2015;49(2):193–202.

14. Nesbit JC, Adesope OO. Learning with concept and knowledge maps: a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res. 2006;76(3):413–448.

15. Pohl CA, Robeson MR, Hojat M, et al. Sooner or later? USMLE Step 1 performance and test administration date at the end of the second year. Acad Med. 2002;77(10):S17–S19.

16. Holtman MC, Swanson DB, Ripkey DR, et al. Using basic science subject tests to identify students at risk for failing Step 1. Acad Med. 2001;76(10):S48–S51.

17. Basco WT, Way DP, Gilbert GE, et al. Undergraduate institutional MCAT scores as predictors of USMLE Step 1 performance. Acad Med. 2002;77(10):S13–S16.

18. United States Medical Licensing Examination. 2018 USMLE Bulletin of Information. Available from: http://www.usmle.org/pdfs/bulletin/2018bulletin.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2017.

Introduction

Introduction The test at a glance:

The test at a glance: