According to national statistics, upward of twenty thousand children left foster care in 2002 after their eighteenth birthday; among children in care, emancipation was listed as the case goal for more than thirty-four thousand children (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007). Not surprisingly, the issue of foster youth has attracted considerable attention, particularly over the past decade since the beginning of the twenty-first century. For the most part, that attention has focused on the transition to adulthood by children who reach the age of majority while still in foster care (that is, while in state custody). Policymakers at the federal level have addressed the problem at least twice. The independent living act of 1985 established a pool of federal resources for youth leaving foster care. more recently, the Foster Care independence act of 1999 (the Chafee act) renewed the focus on children leaving foster care and their preparation for adulthood.

Despite the policy attention, relatively little empirical work has been done to place foster youth (children age thirteen and above) in the broader context of the foster care system. Discussions of foster youth often begin with an image of children who grow up in foster care only to face the transition to adulthood without the benefit of any social connections. Although that is a powerful image, the pathways that adolescents take through the foster care system are often more complex. This chapter addresses a set of basic questions designed to broaden our understanding of adolescents within the foster care system. The first question deals directly with the issue of who grows up in foster care and the portion of childhood that they spent in foster care. The second question relates to the entry of children into foster care, with specific attention to where adolescents fall within the broader context of children entering foster care for the first time and entry rate disparities for white children and black children that take age into account. The third question relates to youth's exits from foster care. youth placed in foster care leave care for a variety of reasons that include reunification, adoption, aging out, and running away.

Foster youth, as described in this chapter, generally refers to children between the ages of thirteen and seventeen. The definition, however, is flexible, depending on the context. From an admission perspective, a definition of foster youth as children between the ages of thirteen and seventeen is workable; from a discharge perspective, it is better to expand the definition to include individuals leaving care at eighteen and older. For other questions, it is useful to consider the experience of children admitted before they turned thirteen.

The issue of youth aging out of foster care has gained salience for the reason that the state has an obligation to shape successful transitions to adulthood for these youth. Because the state has care and custody of the child, it must, as any parent is expected to do, see to it that foster youth have the requisite assets needed to complete a successful transition to adulthood.

Although who grows up in foster care is a straightforward question, very few empirical data are available to answer it. Moreover, from the data that are available, it is difficult to say whether growing up in foster care has become more or less likely over time. The paucity of data is attributable to the fact that, in all but a few states, there are no administrative data that allow the tracking of outcomes for children who entered foster care as young children. as an example, most states do not have data that answer a question such as the following: Of children admitted as babies in 1986, how many spent their childhood through age eighteen in foster care, leaving care in 2004? The same challenges remain in answering questions about children who were admitted to foster care in 1987 at one year of age or older and who may have spent what was “left” of their childhood in foster care once they were placed. Time spent in foster care for these children, however, would represent a declining portion of their childhood, if childhood were measured from birth through age eighteen. Moreover, with each passing year from 1987 through 2004, less and less would be known about how much time was spent in foster care relative to childhood in its entirety because the group of children whose eighteenth birthday has been observed is smaller as time moves closer to the present.

Fortunately, a handful of states have data from 1986 that provide a preliminary answer to this important question. Even with these data, it is difficult to identify trends as from 1986 to the present. There have been a number of policy initiatives designed to influence outcomes for children in foster care. some children placed in foster care in 1986 were in care when each of these policies was put into place by law. For other children, only some of the policy changes would have affected their placement experiences and outcomes.

For this analysis, we look at all children admitted to foster care for the first time from 1986 through 2004. The total number of children is 701,233; the number of children who aged out of placement (that is, were in foster care on their eighteenth birthday and left foster care at that time) is 35,979, or about 5 percent of the total. It is possible to know whether a child aged out of foster care only if we observe the child's eighteenth birthday. For other children admitted since 1986, we will not observe their eighteenth birthdays as of 2004. As these birthdays are observed, the 5 percent will grow over time.

For children admitted as babies, we look at 1986–1987 data to answer the question of how likely it is that a child will spend his or her entire childhood in foster care. The question of how many babies age out of foster care is important because babies make up the largest group of children admitted since 1986. Of the total 701,233 children admitted to foster care, babies accounted for 150,000, or about 20 percent. Unfortunately, relatively little is known about these babies. As noted earlier, only babies from the 1986 entry cohort have been alive long enough to determine whether they were still in foster care upon reaching their eighteenth birthday. The number of babies who aged out is very small. Notwithstanding sources of error in the data (e.g., children who moved to other states or were otherwise lost to the tracking system), only twenty-five children stayed in foster care for their entire childhoods, a figure that represents about one-half of 1 percent of the five thousand infants admitted in 1986.

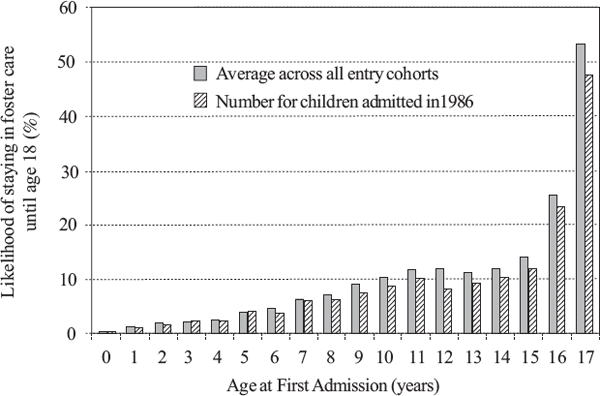

Figure 1.1 Percentage of children aging out of foster care by age at admission, 1986–2004 admissions

In Figure 1.1, data representing the likelihood of entering care and staying in foster care until age eighteen by age at first admission are given for all children between the ages of birth and seventeen. Two sets of data are displayed: the average across all entry cohorts and the specific figures for children admitted in 1986. When viewing the data, it is important to bear in mind that the sample used to compute the average grows by one year with each age group. The figure for babies represents the experience of babies admitted in 1986, the only year for which data are available. For one year olds, there are two years of data available: 1986 and 1987. For seventeen year olds, there are seventeen years of experience to consider, given that any child who entered foster care at seventeen would have been observed to age out if, in fact, they did.

The data show that through age six, fewer than 5 percent of the children in each age group admitted remained in their first placement spell through their eighteenth birthday. Among children between the ages of one and ten, the comparable figure was between 6 and 10 percent. For children between the ages of eleven and fifteen, the percentage of children who aged out was between 11 and 14 percent. The percentage of children who aged out was highest among children admitted between the ages of sixteen and seventeen. About one in four children placed in foster care at age sixteen aged out; among seventeen year olds, the figure was above 50 percent.

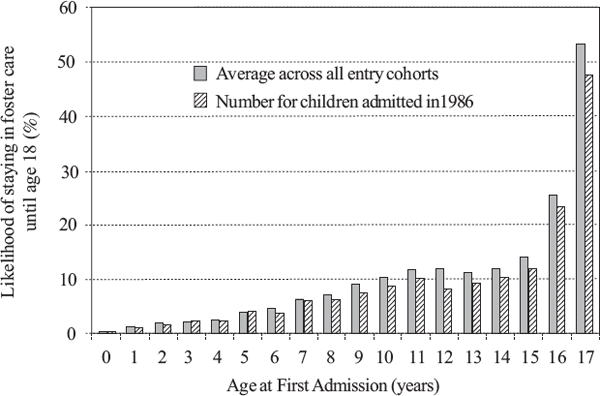

Because a child may move in and out of foster care over the course of childhood, capturing only the time spent in the first placement spell under-states how much time is spent in care relative to childhood. To correct for this downward bias, we calculated total time in care across all placement spells and expressed the result as the percent of childhood. These data, presented in Figure 1.2, are somewhat complicated, again because the level of incomplete data limits what can be said. To resolve these issues, we computed the following:

• Childhood: the number of days between birth and the eighteenth birthday

• Total time in care: the number of days spent in foster care through age eighteen if the eighteenth birthday was observed or the end of observation, whichever came first; for a child placed on the day he or she was born and stayed in foster care through his or her eighteenth birthday, childhood and total time in care would be the same

• Possible observed days: the number of days from the date of first entry into placement through age eighteen; this refers simply to the maximum number of days a child can be in care if he or she were to spend the rest of his or her childhood in care

• Observed days: the total number of days from placement to age eighteen or the end of observation, whichever comes first; the use of the term “observed days” is meant to capture the idea that from the date of placement, the child welfare system has the opportunity to observe what happens to the child through age 18; if the eighteenth birthday is observed, then possible observed days and observed days are one and the same

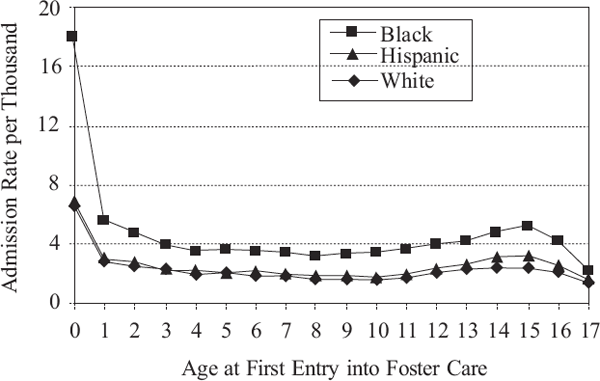

Figure 1.2 addresses two broad notions of childhood. The first is the proportion of childhood (birth to age eighteen) spent in foster care on average. The second is, given the starting date of placement and the time left before a child turns age eighteen, how much of a child's remaining childhood is spent in foster care, given the age at placement. With regard to the proportion of childhood spent in foster care, Figure 1.2 shows that children admitted to foster care between the ages of birth and nine years spent between 20 and 24 percent of their childhood in foster care. Among older children, the proportion of their childhood spent in foster care declines through age seventeen because days in care are counted from the point of first entry. Children placed after age nine have already lived half their childhood outside the foster care system. With each passing year, the percentage of time a child could spend in care goes down as they reach their eighteenth birthday. Understandably, children who enter placement as seventeen year olds spend the least of amount of time in care relative to childhood.

Figure 1.2 Foster care in the context of childhood, 1986–2004 admissions

Figure 1.2 also shows the time spent in foster care as a percentage of how much childhood is left, given a placement in foster care. Viewed in this way, foster care becomes an increasingly important context for growing up. For example, among children age twelve at the time of placement, 45 percent of their remaining childhood is spent in one or more placements. With each additional year, foster care plays an increasingly important role in the life of a child. For children who enter care at age seventeen, more than 70 percent of their remaining childhood is spent in foster care. In other words, foster care represents a small fraction of their childhood, but it is the context that defines the months and days leading up to their eighteenth birthday.

Three issues are important to consider in relation to foster care entry: the risk of entering foster care, entry rate disparities, and placement types.

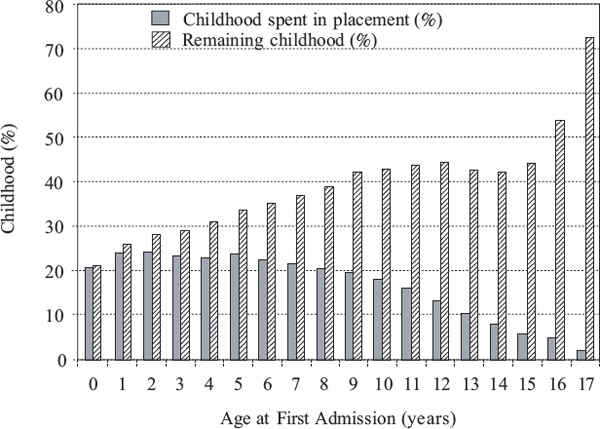

The risk of entry into foster care refers to the probability a child will enter foster care. The risk can be computed in any one of several ways. As a rate per one thousand children in the population, the rate of entry measures the risk of entry within a given population. Figure 1.3 illustrates the admission rates per one thousand children in the general population in 2004. Admissions are counted as first ever admissions in 2004 from a collection of fourteen states that provided data to Chapin Hall and the Center for Foster Care and Adoption at the University of Chicago. The data are presented by single year of age and race in order to place the risk of placement among adolescents within the population of all children.

Figure 1.3 admission rate per 1,000 children by race or ethnicity, 2004

As reported in previously published work (Wulczyn et al., 2005), the data point to persistent risk patterns regardless of race. Among black children, the likelihood of placement is greatest among infants and adolescents, especially adolescents who are age fourteen and fifteen. For these children, the rate of placement is just above five per thousand. Only black babies face a substantially higher risk of placement.

Although uniformly lower than placement rates for black children, the placement rates for white and Hispanic children follow the same general pattern in relation to age. Among whites, fifteen year olds have the highest rate of placement except for white babies; for Hispanics, placement rates are highest for babies and fifteen year olds.

Disproportionality occurs when one population (e.g., black foster children) is out of proportion with respect to an appropriate reference population (e.g., black children in the general population). Differences in the likelihood of entry into foster care are an important component of racial disproportionality.

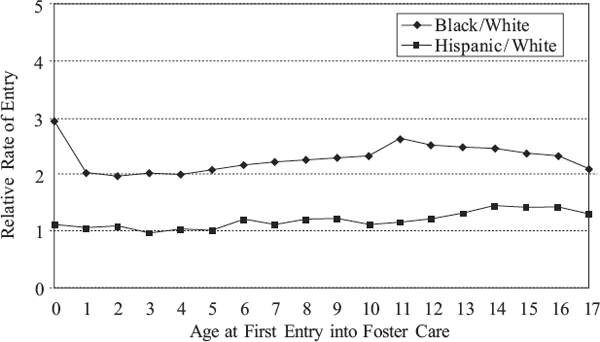

Figure 1.4 Entry rate disparities by age and race or ethnicity, 2004

In Figure 1.4, the data point to the fact that, across all age groups, black children are more likely to enter foster care. The data also suggest that disparity varies across childhood. Figure 1.4 highlights entry rate disparities by age at entry and race or ethnicity. In this figure, two comparisons are offered. The first compares the rate of black placement to the rate of white placement, by age; the second draws the same comparison for Hispanics and whites. In each case, the relative rate of entry is determined by dividing the age-specific rate of entry for white children into the corresponding rate for either black or Hispanic children.

Although significant disparities exist for black children of all ages, the data also point to the fact that disparity is not constant across childhood. For black children, disparity is greatest among young babies. Among children between the ages one and four (preschool years), disparity is approximately one-third lower than it is for babies. Once black children reach school, the disparity rates grow through age eleven, but they never reach the level reported for babies. Among adolescents, disparity rates decline, with the lowest level reached at age seventeen.

Among Hispanics, the general pattern holds, with important exceptions. First, disparity rates are generally lower. Second, disparity among the youngest children is absent. Notwithstanding problems with the coding of race or ethnicity in the source data, Hispanic children are placed into foster care at about the same rate as white children. That said, disparity rates are slightly higher among children in elementary and junior high school. For adolescents, entry disparities grow smaller, although the differences are not as distinct as those observed for whites and blacks.

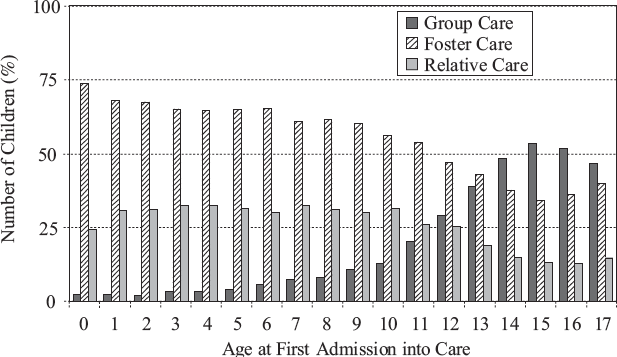

The placement into different care types also varies by age at admission. As Figure 1.5 shows, adolescents are the children least likely to be placed in family-based care. More than one-half the children below the age of twelve spent most of their time in foster care in the home of a family. Another 25 percent or more spent the majority of their placement time in the care of a relative. For children aged twelve and above, group care became the predominant care type. For fifteen year olds, one-half the youth spent the majority of their time in care in a group setting.

Figure 1.5 Predominant placement type by age at admission, 2004

As a developmental construct, age is a useful way to organize data about who enters foster care and how long any given group of children spends in foster care. The same is true for how children leave foster care. Age-structured data reveal patterns that reflect transcendent developmental processes.

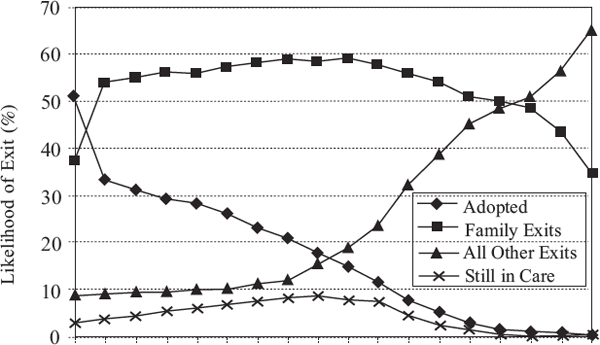

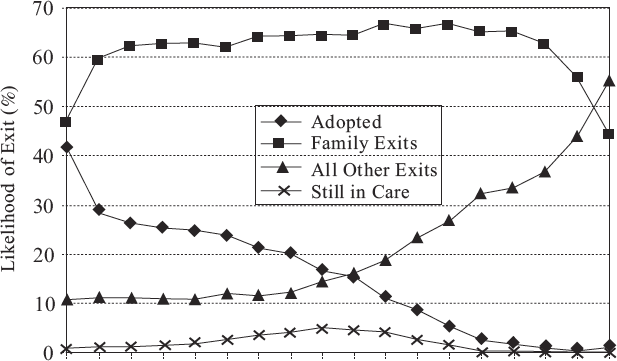

Discharge reasons by the child's age at admission are presented in Figure 1.6 (for black children) and Figure 1.7 (for white children). The data, drawn from a collection of states, show by age the likelihood of each of three exit types. The exit types are family exits (which include reunification, discharge to relatives, and guardianship); adoption; and all other exit types, including running away and aging out. Figure 1.6 and Figure 1.7 also show whether children in the sample were still in care.

Patterns in the data show a remarkable consistency. Babies from this collection of states, whether black or white, are the children most likely to be adopted and the least likely to be reunified. For children generally, adoption rates fall as the age at admission rises. At age thirteen, the likelihood of adoption falls below 5 percent, regardless of whether the children are black or white.

Among all black children, children between the ages of one and nine have the highest reunification rates. At age ten, reunification rates start to decline, and at admission ages sixteen and seventeen, the likelihood of re-unification is below 50 percent for black children. The pattern for white children is generally the same with important differences. Overall, reunification rates are slightly higher for white children. reunification rates for white children drop with age, but the decline starts later in adolescence.

Figure 1.6 Likelihood of exit by exit reason, black children, 1990–1999

Figure 1.7 Likelihood of exit by exit reason, white children, 1990–1999

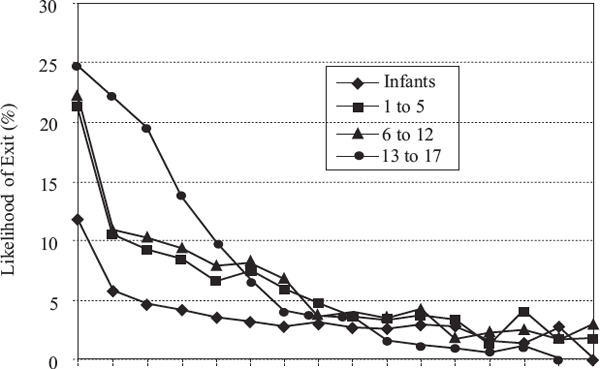

Figure 1.8 Likelihood of exit to reunification by time since admission to foster care and age, 1990–1999

Other exit types grow as the reason that children leave foster care starting around age nine. From a base of about 10 percent of all exits for all children under the age of nine, regardless of race or ethnicity, other exits rise persistently as the age at admission grows from ten to seventeen. Although black youth, when compared with white youth, are more likely to leave placement for other reasons, the basic patterns underscore the importance of the similarities in the developmental processes.

The timing of exit, expressed as a conditional probability in relation to placement duration, is presented in Figures 1.8 and 1.9. Figure 1.8 shows when children are reunified; Figure 1.9 shows the same data for adoption. In each figure, the data are displayed for separate age groups, so that the experience of foster youth is more readily discerned.

These data reveal well-established facts about both the reunification and adoption processes. In the initial six-month period after admission, reunification rates are relatively high, regardless of age. Thereafter, the likelihood of reunification declines rapidly, particularly for children between the ages of birth and twelve at admission. For example, when children are still in foster care six months after admission, the likelihood of reunification during the second six-month period falls by 50 percent. Adolescents have the highest initial rate of reunification, and the change in reunification rates is smaller during the first twelve months. However, by thirty-six months, adolescent reunification rates are below those recorded for children of other ages.

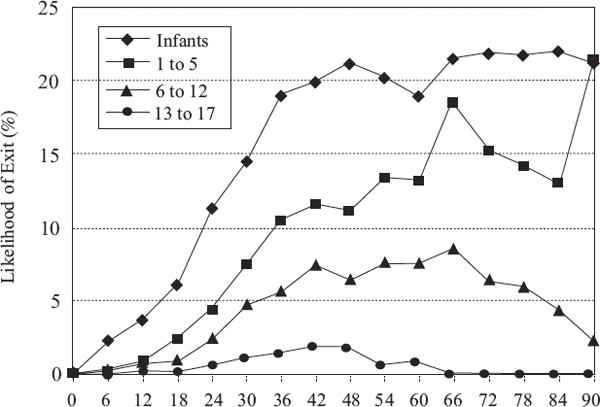

Figure 1.9 Likelihood of exit to adoption by time since admission to foster care and age, 1990–1999

Adoption rates follow a notably different pattern, although the age differences are no less noteworthy. In essence, the adoption process is the mirror image of reunification, with the likelihood of adoption holding at a low rate during the weeks and months immediately after admission. The passage of time (placement duration) brings higher adoption rates for all children, regardless of their age at admission.

What differs is the rate at which the adoption rate changes, given age at admission. Among infants, the rate of adoption rises more quickly and reaches a higher level than is the case for other age groups. For adolescents, the pattern is much less pronounced. The adoption rate for children between the ages of thirteen and seventeen rises as placement duration increases, but the rate of increase is slower and the peak adoption rates are much lower.

The data presented thus far give what might be called a long-term view of children placed in foster care. Data from 1986–1987 suggest that although older children tend to spend a smaller portion of their total childhood in foster care, a good portion of what remains of their childhood is spent in foster care after they are admitted to care. These data also describe what happens to children once they enter foster care, a point of view that further highlights the importance of basic age differences.

In this section, we use data to address the question of what happens to children who were in care at some point during the year they were sixteen. Using data on children who spent one day as a sixteen year old in foster care during 2002, we determined where they were on their eighteenth birthdays. Did they reach the age of majority while still in care, or were they discharged and, if so, how? This more compressed view offers a somewhat more realistic picture of states’ planning processes with older youth.

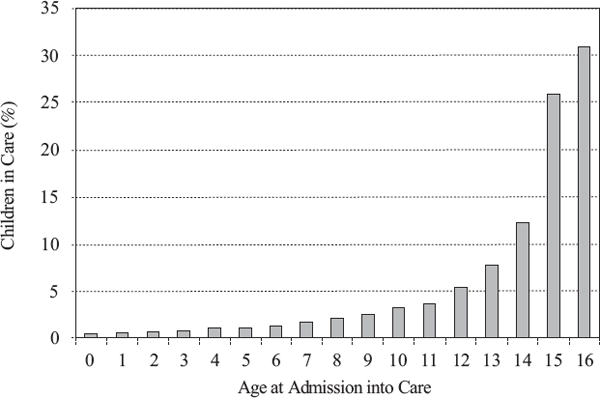

Figure 1.10 Children in care at age sixteen by age at admission, 2002

Figure 1.11 Children in care at age sixteen by exit type, 2002

The initial question is when children in care at age sixteen entered foster care for the first time. As Figure 1.10 shows, not surprisingly, most children in care at age sixteen (56 percent) entered care as either fifteen or sixteen year olds. Children who entered care before their twelfth birthday represent about 25 percent of the children in care at age sixteen, a nontrivial figure. Few of the sixteen year olds entered foster care before their fifth birthdays, although for those children who did, foster care was a significant component of their lives.

Exit data for this population are presented in Figures 1.11 and 1.12. Figure 1.11 shows exits for children in care at age sixteen through their eighteenth birthdays. Permanency rates (adoption, reunification, and discharges to relatives) account for about 43 percent of exits involving youth in care at age sixteen, regardless of age at admission. Nonpermanent exits (other exits not listed separately and running away) account for another 39 percent of the exits. Children who were in foster care at age sixteen and who reached the age of eighteen still in care are listed as having reached majority and represent about 18 percent of all exits.

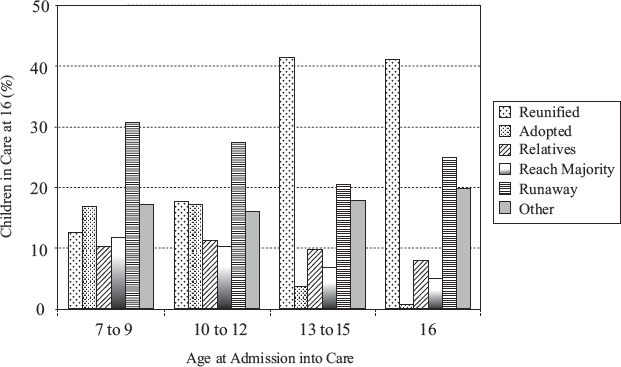

Exit data are also presented in Figure 1.12. These data differ from those in Figure 1.11 in two ways. First, Figure 1.12 takes age at admission into consideration. second, the data show what happened to children in care at age sixteen up to and including their eighteenth birthday. To be counted, youth had to be in care during their sixteenth year and discharged before turning age eighteen. If youth were in care on their eighteenth birthdays, they are listed as having reached majority.

Figure 1.12 Children in care at age sixteen by age at admission and exit status, 2002

Four distinct groups are portrayed: children admitted between the ages of seven and nine, children admitted between the ages of ten and twelve, children admitted between the ages of thirteen and fifteen, and sixteen year olds. Among the groups admitted between the ages of seven and twelve, running away is the most common exit reason (more than 25 percent). Family exits, as a group, account for about 40 percent of the exits, whereas youth who reached majority make up about 10 percent of the children who were under the age of twelve at admission.

Children in care at age sixteen who entered as older children (above the age of twelve) are much more likely to be reunified than are younger children. indeed, reunification is the outcome most often achieved with children who entered care later in their childhood. Adoption rates for older children, however, are very low, and exits to relatives are not common outcomes. The likelihood of reaching age eighteen while still in care is smaller for children who were older at admission.

Although foster youth have attracted a great deal of interest on the part of policymakers and practitioners of late, the focus of that interest has tended to emphasize the transition of foster youth to adulthood. In this chapter, the goal was to broaden our understanding of youth within the foster care system. Two simple questions served as the point of departure: How likely is it that a child will grow up in foster care? How much of childhood is spent in foster care? In addition, in this chapter I consider risk of entry into foster care for older youth compared with children of other ages. Finally, the issue of aging out is examined alongside the other ways children leave placement.

The data presented speak to a need to see the placement of youth in broader terms. First, the data indicate that very few children spend their entire childhood in foster care. Notwithstanding problems tracking children over a long period of time, the likelihood of spending an entire childhood in foster care (from birth to age eighteen) was less than 1 percent of the five thousand infants admitted in 1986. The data did show that that aging out of foster care was most common among children who entered foster care for the first time late in adolescence. On average, slightly more than one-half the children admitted as seventeen year olds were still in care at age eighteen. However, of the children admitted as sixteen year olds, slightly more than 20 percent remained in foster care long enough to reach age eighteen. For children between the ages of nine and fifteen, the likelihood of leaving care at age eighteen fell to between 8 and 14 percent. In short, the likelihood of reaching age eighteen while still in care is relatively rare, except for the children who enter care late in adolescence.

To place these data into fuller perspective, I also examined the portion of childhood spent in foster care. Again, childhood was treated as the period from birth to age eighteen. The data indicate that teenagers (children admitted to foster care for the first time as teens) spend a relatively small portion of their entire childhood in foster care. For example, among children age thirteen and above, less than 10 percent of their entire childhood is spent in placement. That said, among children placed as teens, about 40 percent of what remains of childhood is spent in care.

In sum, the data point to groups of children with distinct placement experiences. younger children spend a greater portion of their childhood in foster care than older children do. When children enter placement for the first time as teens, they may spend a large portion of what remains of their childhood in care, but foster care represents a smaller portion of their total childhood.

Given the desire to improve outcomes for foster youth, these data imply a need to think carefully about program models. Among older youth, work with families falls in the midst of a unique developmental stage. The data suggest that when compared with children between the ages of two and ten, the likelihood of placement rises through adolescence, regardless of whether the children are white, black, or Hispanic. In 2007, Richard Barth (personal communication) argued that older children enter the child welfare system for reasons that revolve around their behavior problems, such as mental health issues, and the ability of their parents to manage those behaviors as opposed to child abuse and neglect more narrowly defined. Simply put, these data suggest that the transition into adolescence may be just as important from a service design and delivery perspective as the transition out of adolescence.

The data also suggest that older youth are more likely to leave foster care for reasons other than aging out of care. For example, children who enter care as adolescents return home more quickly than do younger children. among children in care during the year they were age sixteen, aging out was the least common exit type. Exits to permanency, a category of exit types that includes reunification, adoption, and guardianship, accounted for about 43 percent of the exits compared with just 18 percent for children who aged out. Running away from placement was actually more common than aging out.

Again, these data make it clear that a much broader range of service choices for youth have to be offered. More pointedly, all youth have to negotiate the transition to adulthood. Among youth who have had some experience in the foster care system, youth in care at age eighteen may represent an important target group, but the data indicate that the larger group is composed of those teens who enter foster care close to their sixteenth birthday and exit within the next twelve to eighteen months (before they turn eighteen). For this larger group of youth, services designed to facilitate the transition to adulthood may be best viewed not as an extension of their foster care placement but as family-based and community-based services that connect youth with their families.

In closing, the emphasis on foster youth and their preparation for adulthood within the context of the foster care system acknowledges the important obligations child welfare agencies assume when they place children away from their parents and families. Nevertheless, aging out is but one point in the life course of children. The data presented in this chapter highlight the need to plan interventions with the full span of childhood in view, from birth through the transition to adulthood.

I thank Kristen Hislop for her help preparing the analysis.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families (2007). The AFCARS Report. Washington, D.C.: Author. At www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/afcars/tar/report12.htm (accessed June 7, 2007).

Wulczyn, F. H., R. Barth, Y. Yuan, B. Jones Harden, and J. Landsverk (2005). Beyond Common Sense: Child Welfare, Child Well-Being and the Evidence for Policy Reform. New Brunswick, N.J.: Aldine Transaction.