| Permanence and Impermanence for Youth in Out-of-Home Care RICHARD P. BARTH AND LAURA K. CHINTAPALLI |

FIVE |

Although research makes clear that many children do not achieve permanency, it offers little detail about these children or their paths to impermanence. Much attention has been focused on youth who never achieve permanence and leave foster care without a “forever family” (e.g., Massinga and Pecora, 2004). But there are also many youth who spend time in out-of-home care in a heightened state of impermanence. These youth include those who are not successfully reunified with their birth families and who experience multiple placements while in foster care and youth who no longer have a legal family because their parents’ rights have been terminated.

Permanency is a state of security and attachment involving a parenting relationship that is mutually understood to be a lasting relationship. Permanency achievement is linked to stronger social-emotional development, educational attainment, financial stability, and better health and mental health outcomes (Courtney et al., 2001). Child welfare agencies are expected to achieve permanency for adolescents in foster care by helping them live in families that offer a relationship with a nurturing parent or caretaker and by providing youth with opportunities to establish lifetime relationships and connections with supportive adults.

The child welfare system, however, struggles to find permanent families for children who have reached adolescence. Adolescents in foster care often experience multiple placements and lack connections with significant adults in their lives (Courtney and Barth, 1996; Frey et al., 2005). Permanency attainment may be hindered as a result of youth's behavioral problems (Courtney et al., 2001). Data suggest that reunification and adoption often are not successfully achieved for youth. More than 25 percent of re-unifications of adolescents and their parents fail (Wulczyn, 2004). Only a small proportion of adoptions are of adolescents. In FY 2005, only 15 percent of children adopted from foster care were twelve years of age or older (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). When adolescents are adopted, they face a greater risk of adoption disruption. Adoption disruptions for adolescents may exceed 20 percent (Berry and Barth, 1990).

Many adolescents are neither reunited with their birth families nor adopted, and they “age out” of the system after turning eighteen years old. Approximately 10 percent of the children who exited care during FY 2005 were eighteen years old or older (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). Too many of these youth become homeless, abuse substances, or become involved with crime (Barth, 1990; Courtney and Piliavin, 1998). Runaways also comprise a substantial proportion of all exits from care for older children. In FY 2005, 2 percent (4,445) of the children exiting foster care were listed as runaways (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). Frequency of runaway events for youth ages twelve to eighteen in foster care has increased, doubling between 1998 and 2003 (Courtney et al., 2005).

Placement instability while youth are in foster care contributes to the challenges in achieving permanence for adolescents in foster care and the poor outcomes associated with aging out of foster care and running away. Courtney and colleagues (2005) found that increased placement instability while youth are in foster care increased the risk of an adolescent's running away for the first time. Multiple placement moves combine with the absence of caring relationships with adults, sibling separation, and loss of cultural connections to undermine positive outcomes for youth in foster care. Research with California children in foster care indicated that these factors result in negative outcomes for children and youth, including poor educational performance and behavioral problems (Blome, 1997; Newton et al., 2000).

In this chapter, we discuss research findings regarding the reunification of youth with their birth families and reentry rates for youth who are reunified with their birth families. We then consider placement instability and its role in youth impermanence, focusing on the use of congregate care for adolescents and on running away as the method by which some youth leave foster care. We then consider the use of termination of parental of rights that does not result in adoption and the possibility of posttermination reunification and close with a discussion of the implications for research, policy, and practice.

Data show certain patterns regarding adolescents’ exits from foster care. More than one-half of youth who are in foster care at age sixteen entered foster care as adolescents and are in their first spell of foster care (Wulczyn et al., 2005). These youth are more likely to reunify with their birth parents than are youth who enter care at ages seven through twelve, a group that is more likely to leave care by running away (Wulczyn et al., 2000).

There have been few studies of reunification outcomes for adolescents in foster care, but the studies that have examined these issues suggest that successful reunification is a difficult permanency outcome to achieve for adolescents. In one study that examined planned reunifications involving 149 youth, the researchers found that adolescents were among the groups with the lowest rates of successful reunification (Taussig et al., 2001). Another study of 252 youth ages seventeen or older at time of case closure found that only 10 percent of the adolescents had planned reunifications or permanent placements with relatives; another 10 percent of the adolescents had unplanned reunifications, and 11 percent were runaways (McMillen and Tucker, 1999).

These studies highlight the need to improve reunification efforts for adolescents. More concurrent in-home and out-of-home services are needed, such as combining foster care with the use of Multisystemic Therapy (MST) or Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC) that includes individualized behavior therapy and family therapy. MST is a family-centered model focused on goal-oriented treatment designed to enhance a youth's functioning by building stronger family and positive peer relationships while decreasing antisocial behaviors; the goal is to empower families to develop healthy environments through resources and connections (Henggeler et al., 1986). Similar to MST, MTFC is a family-based approach designed to help and support a youth's family in treating troubled youths by decreasing delinquent behaviors and increasing pro-social activities (Chamberlain and Reid, 1998; Fisher and Chamberlain, 2000). Youth typically reside in MTFC homes and then transition back to their birth family home. MTFC interventions are developed and implemented in various environments, including in the MTFC home, at school, and in the community (Fisher and Chamberlain, 2000).

Family connections are important throughout a youth's foster care experience. When adolescents come into care, youth may not maintain connections with family and friends as a result of agency policies and practices. In some cases, for example, visiting may be difficult to arrange because of agency requirements of criminal background checks for each family member or friend. Reducing barriers to family connections can help adolescents maintain consistent contact with family, friends, and community. In addition, at each opportunity during a youth's stay in foster care, the child welfare agency should assess whether the birth family can serve as a permanency resource for the youth and whether reunification is possible. These assessments may be appropriate after parents’ rights have been terminated and youth have not been placed with adoptive families. Finally, when youth have been reunified with their families, aftercare services should be provided over a period of more than six months.

Information from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) provides a better understanding of reentry to foster care from reunification (Barth et al., 2006). The rate of reentry after reunification is related to the type of placement. Children in congregate care experience the highest reunification rate (nearly 95 percent) and have a reentry rate of 28 percent. Children placed with unrelated foster families experience a reunification rate of almost 88 percent and have a reentry rate of 20.5 percent. The lowest rate of reunification (79.3 percent) is experienced by children in kinship care, and they also have the lowest reentry rate (13.9 percent). Reentry rates also vary in relation to exits from foster care other than through reunification. Some 13 percent of all exits from foster care are to the home of a relative, with a 29 percent rate of reentry to foster care. Among children who run away (about 7 percent of all exits), more than one-half reenter foster care. Though this is not a conventional reentry rate, it is important to recognize that as many as one-half of the children who run away never return to foster care.

Reentry rates differ significantly for children who are placed with unrelated foster parents and those placed with kin. An analysis of NSCAW data revealed that children age seven and older—who were in care for the first time, were placed with unrelated foster parents, and were reunified during the first thirty-six months of care—were more than eight times as likely to reenter foster care than their peers who were placed with kin (Barth et al., 2006). Two explanations for this outcome appear most sensible. First, children who are placed with kin have fewer problems and, as a result, reunifying them with their parents and sustaining those reunifications may be less difficult, resulting in lower reentry rates. Second, children who are likely to have difficulty remaining at home (because of their own difficulties, their parents’ difficulties, or an interaction of these factors) may be less likely to be sent home when they live with kin. The child welfare agency and the courts may be more willing to allow additional time to achieve permanency when children live with kin.

The NSCAW analysis (Barth et al., 2006) also found that other factors were associated with reentry to foster care. Previous involvement with child welfare services was strongly associated with reentry across all the types of initial placements. As has nearly universally been shown in other studies (e.g., Courtney, 1994), the analysis found that the length of time that children spent in foster care before the reunification was associated with the success of reunification. Children with shorter stays in foster care were more likely to reenter care (Barth et al., 2006). The data analysis also showed that reentries into foster care increased with the number of prior reentries. Each time a child returns home and then reenters foster care, the child is more likely to have another failed reunification if he or she again returns home. Compared with the 20 percent of all reunifications that fail after the child's first stay in foster care, 39 percent of reunifications fail after a youth's third entry into foster care.

Placement instability has been defined as three or more moves for a child while in foster care (Webster et al., 2000). Studies suggest that many children in foster care experience placement instability. A California study found that more than 50 percent of children in nonkinship foster care and over 25 percent of children in kinship foster care had experienced at least three moves (Webster et al., 2000). In a study of a large Ohio county, 22 percent of children in foster care had experienced at least three moves (Usher et al., 1999). In Illinois, one study found that over 40 percent of children in foster care had three or more placements (Hartnett et al., 1999). A more recent study in Illinois found that the average number of placement changes for children in their first year of foster rose from 1.7 in 1992 to 2.1 in 2002. This study also found that placement instability was increasing: in 1990, at least 46 percent of children in their first year of foster care had experienced no placement changes compared with fewer than 25 percent of children in their first year of foster care in 2002 (Zinn et al., 2006).

Studies have identified two major causes of placement instability: policy-related or system-related issues, such as the use of nonkinship placements and emergency foster home and shelter placements; and difficulties on the part of foster families or the child welfare agency in meeting children's needs. Mary Ann Hartnett and colleagues (1999) found that in Illinois, more than 50 percent of placement changes occurred as a result of policy or system issues. Sigrid James (2004) found that 70 percent of placement moves occurred because of administrative actions—that is, policy or procedural requirements that caused the placement change (including moving children so that they would be placed with siblings or moving to lesser or more restrictive settings). That study found that only 20 percent of placement changes were the result of children's behavior problems (James, 2004).

Other studies, in contrast, have found that children's behavior and emotional problems account for many placement changes. In a recent Illinois study (Zinn et al., 2006), child welfare workers stated that over 75 percent of placement moves were related, in part, to the foster parent's inability or unwillingness to continue to foster the child because of the child's emotional or behavioral problems (27.6 percent) or personal issues affecting the foster parent, such as divorce, marriage, or change in employment (20 percent). In their San Diego study, Rae Newton and colleagues (2000) found that children exhibiting initial problem behaviors, such as aggression or delinquency, were more likely to experience placement changes. In a national probability study of children in out-of-home care, the rate of placement moves during a thirty-six-month period was four times as great for youth with emotional and behavioral problems than for youth without such problems at the time of placement. There was considerable variation, however, in the number of placement moves for youth with emotional and behavioral problems, indicating that the presence of these problems influenced placement moves but did not determine them (Barth et al., 2007).

Placement changes in the first year and age at initial placement also are significant risk factors associated with placement instability. Daniel Webster et al. (2000) found in a California study that children who had more placement changes in the first year of placement were more likely to experience long-term placement instability. Studies also have found that adolescents are more likely than younger children to experience placement changes (Webster et al., 2000; Wulczyn et al., 2003). Andrew Zinn and colleagues (2006) found that each additional year of age at time of placement increased a child's likelihood of a placement change by 4 percent.

Other factors associated with placement changes among children with emotional and behavioral problems are depression and separation from siblings (Wulczyn et al., 2003), uncertainty or hopelessness about reunification, and age of the child (over ten years old) (Barth et al., 2007).

Among children without emotional and behavioral problems, children who are older and who are female (James, 2004; Wulczyn et al., 2003), who report past psychological trauma, and who are involved with the juvenile or criminal justice system are more likely to have placement changes (James, 2004).

Several studies have linked placement instability to negative outcomes for children, including mental health and behavioral problems and increased delinquency. In a longitudinal study of children who entered foster care in San Diego and who had no presenting behavior problems at the time of placement, Newton et al. (2000) found that placement instability contributed to behavioral and emotional problems; they determined that children who experienced more placement changes were at high risk for increased internalizing, externalizing, and total behavioral problems. David Rubin and colleagues (2007) linked children's multiple foster care placements with increasing needs for mental health services. Joseph Ryan and Mark Testa (2005) found that placement instability experiences before the age of fourteen contributed to increases in delinquency charges after that age.

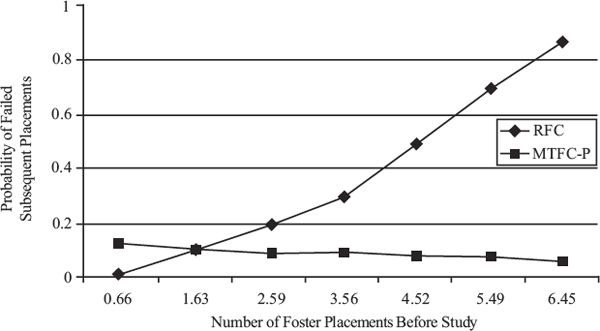

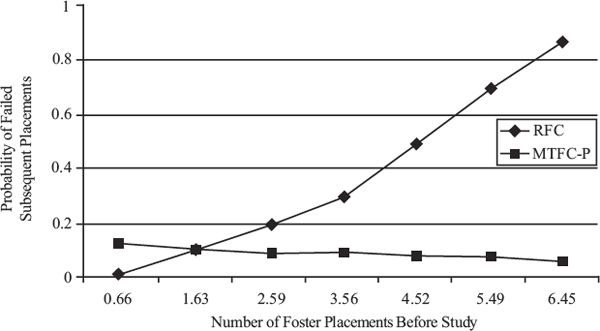

Placement instability is not predestined. Two MTFC-based projects have demonstrated an effect on placement instability and exits. MTFC-P (multidimensional treatment Foster Care—for Preschoolers) showed that, for young children, these services can reduce the influence of previous placements on future placements (Fisher et al., 2005). As shown in Figure 5.1, the placement movements for children who were in regular foster care (RFC) were much different than for children who were randomly assigned to and received MTFC-P. For the children in regular foster care, the more placements that children had before entering the study, the more placements they had after entering the study. This finding reflects the predictable pattern of placement instability generating more placement instability. In stark contrast, the children who received MTFC-P had fewer placement moves after entering the study, and those moves were unrelated to their previous moves. For example, a child with four foster care placements before the study and who received MTFC-P did not experience an increased probability of another failed placement as would be expected for children in conventional foster care. Previous placement moves lost their predictive power for children who were in MTFC-P. Although some children did experience moves, these moves did not depend on previous instability: the trajectory of placement failure was broken.

Figure 5.1 Probability of failed placements by prior placements and condition for children in regular foster care (RFC) and in multidimensional treatment foster care for preschoolers (MTFC-P)

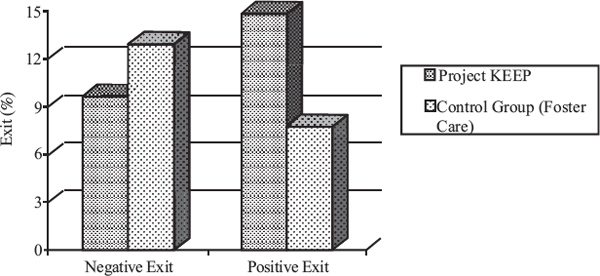

Figure 5.2 Type of exit in Project KEEP and a control foster care group (Chamberlain et al., 2006)

Project KEEP is an intervention program that serves children in foster care ages five to twelve years who are in a new foster care placement and their foster parents or relatives. The program is a less intensive form of MTFC with goals of increasing the parenting skills of foster parents, reducing the number of placement changes for children in care, increasing positive placement moves of reunification and adoption, and improving child outcomes in multiple settings (home, school, and community). Foster parents complete a specific parent management training session and receive support from teams of professionals and other foster parents. Daily parent reports provide information on child behavior problems and foster parent stress levels. The evaluation of Project KEEP is the first randomized trial of an MTFC derivative in a child welfare setting. The evaluation shows that children whose foster parents participated in Project KEEP were less likely to run away or have another negative exit from foster care, had fewer incidents of behavior problems, and had fewer planned and unplanned placement changes (Chamberlain et al., 2006). In addition, children participating in Project KEEP were more likely to be reunified, adopted, or placed with a relative. As shown in Figure 5.2, children who participated in Project KEEP were almost twice as likely to leave foster care for reunification or adoption (Chamberlain et al., 2006).

Preventing or reducing placement instability may reduce youth impermanence. The chain from placement instability to impermanence involves a sequence of moves, with placement instability likely to contribute to a disconnection between the adolescent and the biological family. Each time a child moves, the child may be a little further away, both geographically and psychologically, from family members. With each move, family members must be contacted and informed of the move, contact information must be changed, family members must learn new transportation routes to visit the child, and family must adjust to yet another set of foster parents or group care providers.

Studies are consistent with this conclusion. Madelyn Freundlich and Rosemary Avery (2005) completed a qualitative study of interviews with adolescents and child welfare professionals (seventy-seven total respondents), finding that adolescents in group care have little input into their own permanency planning and that typical permanency planning for adolescents in group care does not focus on work with families. They found that the permanency goal of independent living was used far more often than goals of reunification and adoption for adolescents in group care. The adolescents interviewed felt their connections to their families were severely hindered by their placement in group care as they typically were located far from their families of origin. This distance can contribute to a decrease in visitation and, as a result, present barriers to reunification efforts. Research provides evidence that children who have continued contact with their families of origin after placement in out-of-home care experience less placement instability and are more likely to achieve family permanence (Kupsinel and Dubsky, 1999).

Other studies have found that youth in congregate care settings experience higher levels of placement instability and higher rates of reentry to foster care. Fred Wulczyn et al. (2003) found that older children in group care placements lasting longer than 30 months had higher rates of placement instability. In their study of 2,616 children entering congregate care in 1992 and 1993 in Ohio, Kathleen Wells and Shenyang Guo (1999) found that children whose last placement was a group home reentered care at a faster rate than children leaving a kinship care placement.

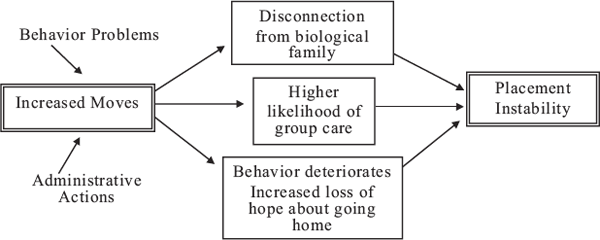

Taken together, the evidence supports a conceptual framework for understanding placement instability that starts with the contribution of youth's emotional and behavioral problems and administrative decisions; results in disconnection from family and, very often for adolescents, placement into residential care; and then, in turn, results in increasingly poor behavior (which may also cause further estrangement from family) and, ultimately, greater placement instability. These relationships are shown in Figure 5.3. It is likely that the relationships are reciprocal, but the research is too limited to inform an understanding of which reciprocal paths are strong and which are weak. This model appears to offer some opportunities for development of interventions that may have direct and indirect effects on impermanence.

Figure 5.3 A general model of placement instability and placement type

Although the use of group care has been declining for much of the last century (Barth, 2005; Wolins and Piliavin, 1964), many adolescents continue to spend time in group homes or residential treatment. Preliminary FY 2005 reports based on AFCARS indicate that 8 percent of children and youth in out-of-home care were in group homes, and an additional 10 percent were in institutions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). These numbers are not disaggregated by age group, but if they were, they would almost certainly indicate that adolescents are the most likely age group to be in group care. In New York City, about one-third of youth ages eleven or older are in group homes or residential treatment centers (New York State Office of Children and Family Services, 2002). In 2001 Wulczyn and Kristen Hislop (personal communication) found in one study that, among youth in out-of-home care at age sixteen, the percentage of youth in periods of foster care defined as “entry into congregate care” ranged from a high of 65 percent in some states to as low as 14 percent in California, with a mean of 42 percent. At the time these youth exited out-of-home care, a mean of about 50 percent were in congregate care.

Group care is a major reason for youth impermanence. Youth in group care experience greater placement instability (Wulczyn et al., 2003; Wells and Guo, 1999; Oosterman, et al., 2007). Given findings that indicate that group care does not outperform treatment foster care or intensive in-home services (e.g., Chamberlain and Reid, 1991; Hengeller et al., 2003) and the extraordinary expense of group care (some residential facilities now cost nearly $200,000 a year), it is likely that the census of children in group care could be reduced, More extensive use of MST and MTFC services and incentives to recruit foster caregivers for adolescents could result in a reduction in the number of youth in group care.

Reducing the number of youth in group care would likely have the salutary effect of providing these youth with more contact with families who might adopt them. Youth who are adopted recount stories of coaches, bus drivers, shift supervisors, and others who develop a close relationship with youth and then agree to adopt them. Although some residential care providers may become adoptive parents, most of them are too close in age to the youth in their care to make adoption a likely event (NSCAW Research Group, 2005). Foster parents continue to be an excellent resource for adoption. In FY 2005, according to the AFCARS report, 60 percent of the children adopted were adopted by their foster parents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006).

Individual, family, and placement factors are associated with high risks of running away. In a recent study, Courtney et al. (2005) found that runaway rates for youth in foster care are higher for females and for older adolescents ages fourteen through sixteen. Adolescents with a history of running away before placement in foster care are at higher risk of running while in care. High levels of family conflict and low levels of family involvement while the youth is in foster care contribute to high rates of running away (Courtney et al., 2005).

The type of placement also is associated with the risk of running away. Placement with a relative caregiver decreases the risk of running away compared with placement with a nonrelative foster family, whereas placement in a residential care facility increases the risk. Other factors associated with running away are repeated foster care placements and the youth's perceptions of the placement setting. When youth consider their placement environments to be warm and caring and when a permanency plan is in place, the risk of running away is reduced (Courtney et al., 2005).

Courtney et al. (2005) found that adolescents typically run to individuals who provide them with a sense of belonging: their family of origin, relatives, friends or romantic partners, or others in their communities of origin. Their reasons for running away vary, from feeling a need to help their parents or siblings to a desire to touch base with their family of origin and know how their family is doing. Some adolescents run at random to the streets or other places. Adolescents who have run away state that running from foster care helps them gain a sense of autonomy and control in their lives, feel “normal,” and have the experiences that they believe they are missing because they are in foster care. Youth also talk about using running as a coping behavior to deal with life in foster care (Courtney et al., 2005).

Based on current research, there is a need to study the family-focused treatment implications of various kinds of running. A national study of children running away from foster care should be conducted. Research is needed to deepen the understanding of the extent to which children's placements in more secure facilities keep them from running away. Studies should focus on assessing whether treatment foster care or community group care can prevent running away behaviors.

Youth who remain in foster care after reunification has been ruled out may have adoption as their permanency goal, a goal that involves the termination of their parents’ rights. The Adoption and Safe Family Act (ASFA)'s emphasis on termination of parental rights, even when an adoptive family has not been identified for the child, is designed to make it more likely that the child will be adopted. The greater likelihood of adoption is the result of two factors: when a child is free for adoption, the child's need for an adoptive family can be pursued publicly, and prospective adoptive parents who may be reluctant to consider a legal risk adoption (that is, accepting a child when both parents’ rights have not yet been terminated) may be more likely to come forward as adoptive family resources. Yet, the extent to which these advantages result in expeditious adoptions for youth is not clear, and growing evidence suggests that this policy may contribute to the impermanence of youth.

The lack of permanency options for older adolescents can result in many youth exiting foster care without connections to family or other supportive adults (Freundlich and Avery, 2005; Frey et al., 2005). As Mark Courtney (chapter 3) and Peter Pecora (chapter 4) point out in this volume, without these connections, youth can be placed in vulnerable positions. Termination of parental rights (TPR) can pose a significant obstacle to permanency for older adolescents who are not adopted because it may prevent possible reunifications between adolescents and their biological parents. Data indicate that a sizable proportion of children whose parents’ rights are terminated will not be adopted. NSCAW data indicate that 33 percent of children whose parents’ rights have been terminated did not have adoption as a plan at thirty-six months after the TPR occurred (Gibbs et al., 2004). As more adolescents become legally free for adoption but are not adopted, the rise in the number of legal orphans—that is, children who have parents but are legally unattached to them—has risen.

TPR is sought based on a variety of reasons. Table 5.1 provides the results of research with child welfare workers about the reasons that the agency seeks to terminate parents’ rights (Gibbs et al., 2004). Although these reasons overlap, they suggest that a sizable proportion of cases result in efforts to terminate parental rights because parents are not actively involved in services, do not change their behavior, or simply run out of time based on legal time frames. The proportion of cases in which TPR was based on abandonment or severe abuse or neglect is less than one-half. These data suggest that many parents permanently lose custody of their children, having done no egregious abusive harm to their children. This finding is consistent with the longstanding evidence that physical abuse and sexual abuse are the least common reasons for child welfare services involvement and continue to become less frequent (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007).

Interviews with youth who have experienced TPR indicate that these youth may experience a number of difficulties (Gibbs et al., 2004). Some youth report that they were not told about the TPR until after the fact, and other youth report that their parents blame them for requesting the TPR (Gibbs et al., 2004). Youth also report frustration that they may no longer be allowed (by their child welfare worker, the foster parent, or group care-givers) to visit their parents after TPR.

For some older adolescents, an important consideration may be reconnecting them with their birth families despite the legal separation created by termination of parental rights. Although reunification with birth parents after TPR may be an option, it must be carefully considered as it is not appropriate for all adolescents. When assessing this possibility, it is important to recognize that birth parents may be at a different point in their lives than when TPR occurred. A parent, for example, may have addressed a substance abuse problem and can now provide a safe home and care for the adolescent. The adolescent should be assessed in relation to self-care skills and self-preservation abilities. Reconnections of youth and birth parents post-TPR must be based on an established relationship in which the youth and parent verbalize a strong desire to be reunified. Reconnections should be considered after other permanency options have been explored and determined not to be viable options for the adolescent. Finally, both the birth parent and adolescent must be linked to strong support systems and be involved in the planning process of reunification.

Typically, post-TPR placement with a birth parent takes place when an adolescent returns home after running away from foster care or returning home after aging out of the foster care system. When an adolescent under the age of eighteen runs away from foster care to return home, the adolescent is considered on run away status and is not generally allowed to remain in the parent's home. Because the birth parent does not have legal custody after TPR has occurred, the parent is not authorized to register the youth for school or consent to medical treatment. In addition, the adolescent is not entitled to inheritance rights once TPR has occurred.

These difficulties can be overcome by allowing a parent to take legal guardianship with respect to the adolescent after TPR. This legal relationship, however, exists only until the child is eighteen years old. After this time, the child is no longer legally connected to the birth parent, again resulting in the loss of inheritance rights. A second method involves birth parents’ pursuit of adoption of their child to regain legal custody. This method reestablishes the legal connection between the adolescent and birth parent, which continues after the adolescent reaches his eighteenth birthday. The process of adoption, however, is time consuming and tedious and may not be feasible for all birth parents. Birth parents who adopt their own children are not eligible for adoption assistance benefits.

Table 5.1 Reasons for Termination of Parental Rights (TPR)

|

RESPONSE (%) |

Parent did not participate in services |

76 |

No change in parental behavior |

73 |

Time limits elapsed |

62 |

Abandonment by parent |

40 |

Severity of abuse or neglect |

35 |

Other reason |

18 |

Parent otherwise incapacitated |

14 |

Parent incarcerated for long sentence |

11 |

NOTE: Reasons are not mutually exclusive.

SOURCE: Gibbs et al. (2004).

A third method of family reconnection post-TPR is the court's reversal of the TPR order. When the order is reversed, the birth parent regains all parental rights. Less time consuming than adoption, this method may provide a birth parent and adolescent the best option for maintaining a legal connection before and after the youth turns eighteen. At least two states have enacted laws allowing for TPR reversals: California and New York.

In January 2006, California enacted legislation allowing an adolescent in foster care to petition the court to reinstate her birth parents’ legal rights. Under California law, the birth parent's rights must have been terminated at least three years before the adolescent's petition; other permanency options must have been considered and deemed unlikely as options for the adolescent; and sufficient evidence must be presented that reversing TPR is in child's best interests and the birth parent is able and willing to raise the child (Riggs, 2006).

In June 2003, New York passed Section 5015 of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules to allow for TPR reversals. Unlike California law, there are no established criteria stipulating when reversals can be brought before the court. Similar to California law, however, the motion to vacate the TPR needs to be supported by evidence that it is in the child's best interest; the parent is ready, willing, and able to care for the child again; and others involved in the case (such as the case worker and guardian ad litem) support the decision. If reunification occurs, the family is monitored by the agency for three to six months (Riggs, 2006).

In all, the TPR reversal process is not easy for parents, adolescents, child welfare workers, and the court system to undertake. All parties involved must diligently assess the information and work together to determine what is in the best interest of the adolescent.

Rates of youth impermanence are high. National estimates of impermanence, however, are not sufficient. The Child and Family Service Reviews (CFSRs) currently monitor replacements into care (reentries) and placement moves (replacements). Two other forms of replacement or rein-volvement with foster care are not counted: replacements of children to other relatives outside of the formal foster care program, and new abuse reports for children who are in care or who have returned home from care (which are not counted unless the new abuse reports trigger a placement move). A national accounting is needed of children in foster care whose parents’ rights have been terminated and the proportion of children who emancipate from foster care whose parents’ rights have been terminated. More precise measures of permanence will provide child welfare agencies with the information they need to modify or develop new policies and practices to achieve permanency goals for all children and youth in foster care.

Because many youth enter care as youth, child welfare agencies should be required to report CFSR data separately for youth who enter out-of-home care as youth. The CFSR process should include a special set of youth-focused outcome indicators, including re-abuse, running away, reentries to foster care, permanency, and postpermanency indicators. Child welfare agencies should have performance standards regarding the achievement of placement stability, keeping youth in family-like settings, and permanence for youth. They should be allowed to achieve these goals as they see fit and in relation to the best interests of individual youth. In the area of youth services, where there is limited knowledge but there is a clear understanding that youth have different needs and characteristics than younger children, an outcome-informed management approach is needed.

Now ten years old, federal policies and practices regarding TPR must be carefully reexamined. ASFA has specific requirements regarding TPR that states must follow to receive federal funding. For adolescents, the ASFA requirement that proceedings for TPR must be initiated when a child has been in foster care for fifteen of the past twenty-two months may hinder reunification efforts for adolescents in care. One option is that child welfare agencies not be required to move forward with TPR for youth as they do with younger children, terminating parental rights when no adoption resource is available.

The resumption of the federal Title IV E waiver option would allow states to test whether they can increase adoptions without increasing the number of youth who emancipate from foster care as legal orphans. This is a testable question, but it has not been answered. Instead, it has been assumed that the best way for all children to be adopted is to first terminate their parents’ rights. This practice belies the ability of youth, regardless of their TPR status, to identify persons who might adopt them. Because youth can be engaged in the decision whether or not to be adopted and can participate in the recruitment of an adoptive parent, they are fundamentally different from younger children. Arguably, youth should be exempt from TPR requirements under ASFA. Adoptions can occur without first requiring TPR by working with youth to help them identify members of their families and broader social networks who might be willing to adopt them and developing those adoption resources before TPR. Other TPR reforms are needed, including the broader institution of policies that permit TPR reversals for youth who have not been adopted and whose parents regain their parental capacity. Adolescents must receive assistance as they prepare to leave care, with independent living services that evolve to address the needs of reunified youth, as well as other youth who leave foster care to other permanent families or to live on their own.

Barth, R. P. (2005). Residential care: From here to eternity. International Journal of Social Welfare 14: 158–62.

Barth, R. P., S. Guo, E. Caplick, and R. L. Green (2006). Exits from out of home care to permanency by 36 months. Unpublished ms.

Barth, R. P., E. C. Lloyd, R. L. Green, S. James, L. K. Leslie, and J. Landsverk (2007). Frequent moving children in foster care: Predictors of placement moves among children with and without emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 15: 46–55.

Berry, M., and R. P. Barth (1990). A study of disrupted adoptive placements of adolescents. Child Welfare 69(3): 209–25.

Blome, W. W. (1997). What happens to foster kids: Educational experiences of a random sample of foster care youth and a matched group of non-foster care youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 14: 41–53.

Chamberlain, P., and J. Reid (1991). Using a specialized foster care community treatment model for children and adolescents leaving the state mental hospital. Journal of Community Psychology 19(3): 266–76.

— (1998). Comparison of two community alternatives to incarceration for chronic juvenile offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66: 624–33.

Chamberlain, P., J. M. Price, J. B. Reid, J. Landsverk, P. A. Fisher, and M. Stoolmiller (2006). Who disrupts from placement in foster and kinship care? Child Abuse and Neglect 30: 409–24.

Courtney, M. E. (1994). Factors associated with the reunification of foster children with their families. Social Service Review 68: 81–108.

Courtney, M. E., and R. Barth (1996). Pathways of older adolescents out of foster care: Implications for Independent Living Services. Social Work 41(1): 75–83.

Courtney, M. E., I. P. Piliavin, and A. Grogan-Kaylor (1998). Foster Youth Transitions to Adulthood: Outcomes 12 to 18 Months After Leaving Out-of-Home Care. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison, School of Social Work and Institute for Research on Poverty.

Courtney, M. E., I. P. Piliavin, A. Grogan-Kaylor, and A. Nesmith. (2001). Foster youth transitions to childhood: A longitudinal analysis of youth leaving care. Child Welfare 80: 685–717.

Courtney, M., E., A. Skyles, G. Miranda, A. Zinn, E. Howard, and R. Goerge (2005). Youth Who Run Away from Substitute Care. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

Fisher, P. A., and P. Chamberlain (2000). Multidimensional treatment foster care: A program for intensive parenting, family support, and skill building. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 8(3): 155–64.

Fisher, P. A., B. Burraston, and K. Pears (2005). The Early Intervention Foster Care program: Permanent placement outcomes from a randomized trial. Child Maltreatment 10: 61–71.

Freundlich, M., and R. J. Avery (2005). Planning for permanency for youth in congregate care. Children and Youth Services Review 27: 115–34.

Frey, L. L., S. B. Greenblatt, and J. Brown (2005). An Integrated Approach to Youth Permanency and Preparation for Adulthood. New Haven, Conn.: Casey Family Services.

Gibbs, D. A., R. P. Barth, B. T. Dalberth, J. Wildfire, S. R. Hawkins, and S. Harris (2004). Termination of Parental Rights for Older Foster Children: Exploring Practice and Policy Issues. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hartnett, M. A., L. Falconnier, S. Leathers, and M. Testa (1999). Placement Stability Study. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois, Children and Family Research Center, School of Social Work.

Henggeler, S. W., J. D. Rodick, C. M. Borduin, C. L. Hanson, S. M. Watson, and J. R. Urey (1986). Multisystemic treatment of juvenile offenders: Effects on adolescent behavior and family interactions. Developmental Psychology 22: 132–41.

Henggeler, S. W., M. D. Rowland, C. Halliday-Boykins, A. J. Sheidow, D. M. Ward, J. Randall, S. Pickrel, P. Cunningham, and J. Edwards (2003). One-year follow-up of multi-systemic therapy as an alternative to the hospitalization of youths in psychiatric crisis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42: 543–51.

James, S. (2004). Why do foster care placements disrupt? An investigation of reasons for placement changes in foster care. Social Service Review 78(4): 601–27.

Kupsinel, M. M., and D. D. Dubsky (1999). Behaviorally impaired children in out-of-home care. Child Welfare 78(2): 297–310.

Massinga, R., and P. I. Pecora (2004). Providing better opportunities for older children in the child welfare system. Future of Children 14(1): 151–73.

McMillen, J. C., and J. Tucker (1999). The status of older adolescents at exit from out-of-home care. Child Welfare 78(3): 339–61.

NSCAW Research Group. (2005). National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being: Baseline Report. Washington, D.C.: Author.

Newton, R. R., A. J. Litrownik, and J. A. Landsverk (2000). Children and youth in foster care: Disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abuse and Neglect 24(10): 1363–74.

New York State Office of Children and Family Services (2002). 2001 Monitoring and Analysis Profiles with Selected Trend Data. Albany, N.Y.: Author.

Oosterman, M., C. Schuengel, N. W. Slot, R. A. R. Bullens, and T. A. H. Doreleijers (2007). Disruptions in foster care: A review and meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review 29(1): 53–76.

Rubin, D. M., A. L. R. O'Reilly, X. Q. Luan, and A. R. Localio (2007). The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics 119(2): 336–44.

Ryan, J. P., and M. F. Testa (2005). Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review 27(3): 227–49.

Taussig, H. N., R. Clyman, and J. Landsverk (2001). Children who return home from foster care: A 6-year prospective study of behavioral health outcomes in adolescence. Pediatrics 108(1): 7–14.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families (2006). The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2004 Estimates as of June 2006. Washington, D.C.: Author.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families (2007). Child Maltreatment 2005. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Usher, C. L., J. B. Wildfire, and D. A. Gibbs (1999). Measuring performance in child welfare: Secondary effects of success. Child Welfare 78: 31–51.

Webster, D., R. P. Barth, and B. Needell (2000). Placement stability for children in out-of home care. Child Welfare 79(5): 614–31.

Wells, K., and S. Guo (1999). Reunification and reentry of foster children. Children and Youth Services Review 21(4): 273–94.

Wolins, M., and I. Piliavin (1964). Institution and Foster Family: A Century of Debate. New York: Child Welfare League of America.

Wulczyn, F. H., K. B. Hislop, and R. M. Goerge (2000). Foster Care Dynamics 1983–1998: A Report from the Multistate Foster Care Data Archive. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

Wulczyn, F. H., Kogan, J., and B. J. Harden (2003). Placement stability and movement trajectories. Social Service Review 77(2): 212–36.

Wulczyn, F. H., R. P. Barth, Y. Y. Yuan, B. Jones-Harden, and J. Landsverk (2005). Evidence for Child Welfare Policy Reform. New York: Transaction De Gruyter.

Zinn, A., J. DeCoursey, R. Goerge, and M. Courtney (2006). A Study of Placement Stability in Illinois. Working Paper. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.