9

The Evolution of Comparative Psychology

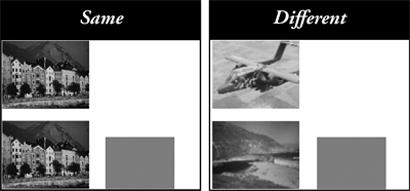

Imagine yourself as a laboratory pigeon. Each day you are placed in a wooden box. Mounted on one wall is a computer monitor with a touch screen. That box is your world. In your world, two vertically aligned pictures and a white square appear on the screen (see Figure 9.1). At first, these pictures mean nothing to you and you do not do anything with them, but through experience these pictures become meaningful. You learn that when the two pictures are the same and you touch the bottom picture you are rewarded with food, but if you touch anywhere else you receive nothing. When the two pictures are different and you touch the white square, you are rewarded with food, but if you touch anywhere else you receive nothing. To survive you must eat, and so to survive in your world, you change your patterns of behavior from doing nothing with the pictures to reliably touching the bottom picture when the pictures are the same and touching the white box when the pictures are different. Changes in behavior patterns that help animals survive in their worlds are what we call learning. Comparative psychologists are interested in the systematic ways that behavior patterns change not only for pigeons but for all animals, including humans.

Arguably, the most important person in the creation of comparative psychology was Charles Darwin. As a child, Darwin developed a curiosity about animals and began learning the names of every animal around his English home while helping his brother with insect and bird experiments.

Sidetracking from this interest in nature, and perhaps following in his father’s footsteps, he initially studied medicine but found surgical practice upsetting so he neglected his studies. Instead he spent his time with the Plinian society, a group of people who supported natural studies. After Darwin left medical school, his father then encouraged him to study theology; he lost interest in that, too. It seemed that nothing could pique Darwin’s interest the way nature could. While continuing his core work in theology, Darwin also embraced his love of nature by taking courses such as botany and geology.

Finishing his degree, Darwin continued to expand his knowledge of nature on a five-year overseas tour. On this trip, he discovered a great number of new species, both extinct (as evidenced by their fossil remains) and living. Darwin noted the physical similarity between the extinct species and many of the living species he encountered. This realization caused Darwin to wonder by what mechanism new species replaced extinct ones. After more study, his answer would be evolution, which he described in On the Origin of Species, which was so popular that it sold out the first day it was available.[1]

In Origin of the Species Darwin focused on evolution with regard to physical continuity across species. Evolution described how existing organisms changed over time to survive in their worlds. Importantly, evolution is concerned only in maximizing survival value, not in advancing toward a specific end. A common misconception, known as scala naturae, is that evolution has led to the most advanced animal, the human.[2] Scala naturae can lead to inappropriate questions about the “best” or “most advanced” way to perform a specific task, without considering an animal’s environment. For example, most water animals have gills to help extract oxygen; but to breathe outside water, land animals have lungs. Both gills and lungs are adaptive features, but which is most advantageous depends on your world (water or land).

In his second major book on evolution, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Darwin extended his thoughts on evolution from physical continuity to mental continuity. In this book he described how, like physical features, mental abilities can change to aid survival in one’s world. Laying the foundations for comparative psychology, he stated that:

All [animals] have the same senses, intuitions, and sensations—similar passions, affections, and emotions, even the more complex ones, such as jealousy, suspicion, emulation, gratitude, and magnanimity; they practise deceit and are revengeful; they are sometimes susceptible to ridicule, and even have a sense of humor; they feel wonder and curiosity; they possess the same faculties of imitation, attention, deliberation, choice, memory, imagination, the association of ideas, and reason, though in very different degrees.[3]

The key thing about Darwin’s observations is that while he did note mental differences between species, those differences were of “degree” (quantitative) and not of “kind” (categorical). Put another way, of course humans can do some things other animals cannot do, but it is possible that everything a human can do, many other animals can do to a different extent. For example, while humans build skyscrapers, ants build tunneled mounds; while humans court love through poetry, birds court love through song; and while humans save extra money, nutcracker birds store extra food.

While Darwin made spectacular observations regarding mental continuity across species, systematic study needed to unfold to capture more precisely that continuity. One of the first attempts to capture animals’ intellectual behaviors was undertaken by Darwin’s friend George Romanes. Like Darwin, using an anecdotal method (which involved observing behavior and making inferences about the behavior but not experimentally testing the inferences), Romanes observed and eloquently wrote about the intellectual characteristics of animals’ behavior. For example, after watching a cat open a latched door to escape from a room, he wrote,

Cats in such cases have a very definite idea as to the mechanical properties of a door. . . First the animal must have observed that the door is opened by the [human] hand grasping the handle and moving the latch. Next, she must reason . . . If a hand can do it, why not a paw?[4]

Romanes colorfully recounted the intellectual feats of not only cats but also ants, dogs, primates, etc. He expressed that his anecdotal work would map “animal psychology for the purposes of subsequent synthesis,” which acknowledges a major weakness of the anecdotal method.[4] This weakness is that the anecdotal method relies on a single observed event to capture the complicated nature of a learning process which unfolds across many events. Emphasizing this problem, Conway Lloyd Morgan stated that single observations, no matter how careful, would not be adequate for the interpretation of an animal’s behavior.[5] Another problem with the anecdotal method is that it enables one to easily exaggerate species abilities, often by implicitly assuming the animals are solving the tasks in a human way (i.e., an anthropomorphic analogy). For example, perhaps the cat learned to open the latch not after a complicated process of reasoning about the mechanical properties of a door, but instead after a more simple process of random trial and error. Morgan captured his thoughts in his statement (“Morgan’s Canon”) that still guides the work of many comparative psychologists: “In no case may we interpret an action as the outcome of the exercise of a higher psychical faculty, if it can be interpreted as the outcome of the exercise of one which stands lower in the psychological scale.”[5]

Around the time “Morgan’s Canon” took hold of comparative psychology, Edward Lee Thorndike was already using a Darwinian framework in his comparative psychology research program. Thorndike formulated a general learning theory that describes how animals learn based on the consequences of their behaviors. Like Romanes, Thorndike also observed cats opening doors. Instead of escaping from a large room, however, Thorndike’s cats escaped from small puzzle boxes in precisely determined ways (e.g., by pulling a string). Rather than hypothesizing about and discussing the cats’ complicated reasoning about mechanical properties, Thorndike simply analyzed the amount of time it took the cat to escape from the box across repeated experiences of being trapped.

Thorndike observed that the cats seemingly did not apply any complicated, purposive strategy. Instead, the cats behaved randomly until they hit upon the right response and escaped (i.e., trial and error). Repeated experience in the box led the cats to repeat the same series of behaviors, such as spin around — claw front — claw left — claw right — pull string — escape box. Behaviors that did not lead to escape were gradually “stamped out” (e.g., spinning and clawing) and behaviors that aided escape were “stamped in” (e.g., pulling a string). Eventually, only the behaviors that led to escape remained, and the time it took the cat to escape decreased across repeated experiences. Thorndike summarized his observations in his “law of effect,” which states that the likelihood of a response’s recurrence is generally governed by its consequence.[6]

Although the law of effect seems obvious to us now, Thorndike’s work was critical in establishing its usefulness across various environments and species. For new environments, Thorndike introduced the cats to new boxes. He noted that in the same way escape times from the original box decreased with repeated trials, the time it took the cats to escape from the new boxes decreased. For new species, Thorndike directly compared the ability of fish, chickens, cats, dogs, and monkeys to perform an equivalent task, altering the puzzle boxes only to account for the physical differences between species (e.g., a fish’s box must be in water). While some species escaped faster than others, the time it took each species to escape from their boxes decreased with repeated experience. The later application of the law of effect to various animal species shows the vast amount of continuity between species mental abilities, strengthening Darwin’s original notion that mental differences among species were “of degree and not of kind.” That is, the decrease in time and the ability to escape a puzzle box indicate species share the same mental faculties to solve the puzzles, whereas the fact that some species learn faster than others is a difference in degree.

Years later another highly regarded psychologist, Burrhus Frederic Skinner, extended Darwin’s original ideas about evolution to impact the way we think about natural selection from the genetic level to behavior at the individual and group levels. He discussed how all levels of selection (genetic, individual, and group) function to increase the likelihood of features (genes, behaviors, or rituals) that aid an organism’s survival and decrease the likelihood of features that are harmful. At the genetic level, genes that aid survival become increasingly likely in future generations; for instance, humans have a genetic code to produce lungs, rather than gills, to breathe. At the individual level, behaviors that aid survival—such as the pigeon touching the bottom picture when it is the same as the top picture (see Figure 9.1)—become increasingly likely in the future. Finally, at the cultural level, rituals that aid survival become increasingly likely in the future: greeting another person by shaking hands if you live in the United States or slightly bowing if you live in China to ensure future pleasant interactions.

Although researchers like Thorndike and Skinner explored the fundamental properties of learning and stressed continuity across species’ mental abilities, much of their research focused on purposely simplified worlds and seemed to indicate that animals learned through trial-and-error processes. But the real world is more complex than such laboratory devices as boxes, and although learning may be simple in a simplified world, it does not follow that learning is simple in a complex world. In their defense, much of the work of early behavioral psychologists aimed at providing mechanistic explanations for behavior, in stark contrast to the anecdotal method.

Working in the Canary Islands, Wolfgang Köhler studied more complex learning by observing problem-solving behavior in chimpanzees. In a typical problem-solving task, a banana would be placed outside of the chimpanzee’s cage, or inside the cage, but too high for easy access. The chimpanzees learned to use sticks to fetch the faraway bananas and stacked boxes to reach the bananas attached to the ceiling of their cages. Although these stick and box tools are less complicated than the tools that humans use, they are indeed tools, and so this research again supports Darwin’s notion that differences between species are “of degree and not of kind.”

Unlike Thorndike’s results, Köhler’s results suggest that the chimpanzees solved tasks purposively. Rather than a gradual stamping-in process of trial-and-error learning, Köhler’s chimpanzees were able to solve the problem using insight. Just as humans solve brain teasers, Köhler’s chimpanzees had no success until they figured out the answer (an “aha” moment), then they were extremely accurate. Problem-solving research continues to this day across species, and the methods different species use to solve problems shed light on how their mental abilities evolved.

Discoveries of intelligent behavior in animals continue to appear at an accelerated rate. Although examples of ape and monkey intelligence are not too surprising, even avians are casting off their “bird brain” label. Pigeons, for example, can navigate by landmarks, sun compass, magnetic compass, and infrasound sources. Galapagos finches and New Caledonian crows select and fashion tools (e.g., cactus spines twigs and leaves) to “fish” out insects and grubs in tree limb holes or cracks or under leaf detritus and carry their favorite tools around with them. Clark’s nutcracker birds store thousands of pine seeds in hundreds of cache sites with sites varying yearly and often covered with snow by the time they are retrieved. These examples provide concrete support for shared, general processes across distally related species.

Although mental continuity is a hallmark of Darwin’s theory, there is an important corollary: animals should also develop specific abilities based on the worlds in which they live (i.e., ecology-specific abilities). While basic mental abilities may be the same across species, organisms should have differences based on when and where they evolved. For example, bats hunt for food during the night so they have developed a specific ability to use echolocation, a series of clicking noises that echo back to them and allow them to judge the distance between themselves and their prey, (i.e., to locate food). Humans, on the other hand, hunt (or shop) for food during the day and can rely on vision to find nourishment. While there are cases of humans successfully using echolocation, the specific ability to use echolocation is less precise in humans, again supporting Darwin’s notion that differences between species are “of degree and not of kind.”

The last 30 years have seen an increase in this ecological research, exemplified by the work of Sara Shettleworth and her ecological program, which emphasizes how the world influences the development of particular mental abilities.[7] Shettleworth cautions researchers to avoid an anthropocentric (human-centered) research focus, which does not consider species’ ecologies, asking, for example: Can nonhuman animals escape from boxes like humans, or, Can nonhuman animals remember where food is located like humans? Instead, she suggests that researchers study closely and distally related species to better understand the impact of specific ecologies. The researcher is then challenged with identifying and manipulating the critical parameters, such as the delay between seeing a clue that indicates where food is located and a later opportunity to obtain it in a memory task. By systematically manipulating the critical parameters patterns often emerge that allow for more appropriate comparisons across species. For example, while all species may find it more difficult to remember something as time passes (a qualitative similarity), quantitative differences may emerge in how quickly a given species’ performance declines over time.[7]

In summary, to better understand the genetic and ecological contributions to mental abilities one should compare closely and distally related species with a conceptually equivalent task. Debora Olson did just that to compare memory for food storing birds: she directly compared the spatial memory of Clark’s nutcrackers to a closely related species, the scrub jay, and a more distally related species, the pigeon, in an equivalent spatial-memory task.[8] If spatial memory was a genetically determined ability, then one would expect the closely related birds to perform more similarly than the distally related birds.

In her task, each bird was placed in a box with four buttons in the front and one button in the rear. In the box, birds touched buttons to receive rewards. In a trial, the rear button illuminated first, which the bird touched to extinguish. Then one of the four buttons at the front (a sample location) illuminated, which the bird also touched to extinguish. Then the rear button illuminated again, and after the bird extinguished it, a waiting period began (e.g., a 1-second delay). After the delay, two of the front buttons illuminated. Now the bird had to decide which button to touch. If the bird chose to touch the button that it had not previously touched, then it was rewarded with food; otherwise, it was not. A correct choice would indicate the bird’s accurate memory for a spatial location. On the next trial, the period of delay between touching the rear button and the choice buttons illuminating was determined by how the bird performed on the previous trial. If the bird responded correctly on the previous trial, then the delay lengthened; however, if the bird had responded incorrectly, the delay decreased. Progressing and performing accurately at longer delays indicated better memory for spatial locations over longer intervals.

Differences of degree but not of kind were found between the species. All birds tolerated delays over 0 seconds (the front buttons are lit immediately after the rear light extinguishes), indicating all species were able to perform the spatial memory task. However, differences emerged in the delay length that each species could tolerate. Pigeons tolerated the shortest delays, .5 to 25 seconds, followed by the jays, 7 to 44 seconds, and finally the nutcrackers, 50 to 80 seconds. Later experiments revealed that species differences between caching birds, like nutcrackers, and non-caching birds, like pigeons and jays, emerged only in spatial memory tests. When caching and non-caching birds’ performances are compared without the spatial component, their ability to remember is very similar.[9] These results show that nutcrackers have a sophisticated species-specific ability to remember spatial locations that is quantitatively better but not qualitatively different than pigeons and jays.

To summarize, the ecological program’s goal is to directly compare the performance of closely and distally related species in equivalent tasks to learn about genetic and ecological contributions to mental abilities. If closely related species that live in different ecological niches perform similarly, it is assumed that those mental abilities are more influenced by genetic than ecologic contributions. Alternatively, when two distally related species that live in the same environment perform tasks similarly, it is assumed that those mental abilities are more greatly influenced by ecological than genetic contributions. In short, when genetic differences are large, the environmental influence is small, but when the genetic differences are small, the environmental influence is large.

Currently, comparative psychologists study a diverse array of topics, from simple processes, such as sensations, to more complex processes, such as episodic memory, language use, imitation, and reasoning, just like Darwin outlined more than 100 years ago. These research programs ask, and provide initial answers to, important comparative questions, but many do not use direct comparisons in equivalent tasks, like Thorndike’s puzzle box or Olson’s spatial memory research programs. As one contemporary example, research in our laboratories has focused on another area of comparative cognition, the development and deployment of abstract concepts in humans, monkeys, and pigeons. Our findings show the extent to which abstract-concept learning is a general process conserved across diverse species.

Abstract concepts are a type of knowledge that transcends the specific items used to represent them. For example, when you were young you learned item-specific math problems, like 2 times 2. Currently, there is no need for you to do any math to confidently answer that problem because you have memorized the answer item specifically and know it by rote (the answer is obviously 4). However, if you are presented with a math problem that you have not memorized, like 456 times 23, you could answer it without having past experience with it because you know abstract math concepts (in this case, multiplication rules). If you do not believe it, get out a pad of paper and do the equation and then check your answer with a calculator. Our laboratory has chosen to focus on a more fundamental abstract concept, same/different. This concept is abstract in the same way the math concept is abstract. To prove it to yourself, hold any two objects in front of you and state if they are the same or different. The objects (such as pens or pencils) themselves are not same or different, but the relation between any two objects can be the same (two pens) or different (a pen and a pencil).

In our research program we directly compare different species in an equivalent task. In this task, two pictures and a white square appear on a computer screen. If the two pictures are the same, the correct response is to touch the bottom picture; if the two pictures are different, the correct response is to touch the white square (see Figure 9.1).

Stimulus Displays

Figure 9.1 - The stimulus displays used to train the humans, rhesus monkeys, capuchin monkeys, and pigeons. A touch to the bottom picture was correct on same trials. A touch to the gray rectangle was correct on different trials. The actual stimulus displays did not have labels, had black backgrounds, and the gray area to the right was white.

After learning the task with eight specific pictures, novel pictures are introduced. If our subjects can perform the task accurately with novel pictures, we can say that the subjects have the abstract same/different concept. However, if the subjects perform less accurately with the novel pictures than the trained pictures, then we cannot say they have fully learned the abstract same/different concept. Instead, we can say they likely learned item-specific rules to perform the same/different task with specific pictures. (This is just like solving 2 times 2 but with pictures. Consider taking a math exam on multiplication. If you solved all the problems correctly and received a 100, you fully learned the abstract math concept, but if you answered only 70 or 80 percent correctly, you have only partially learned that math concept.) But this is not where our experiments end. Instead the training set size is increased to include more pictures, and subjects are tested with novel pictures after learning the task with progressively larger training set sizes ranging from 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1,024 pictures.

Let us start with humans’ performance in our same/different task. Humans can be difficult to test because they enter our laboratory with so much previous experience related to the same/different concept. And while we assume that all of our college-age participants have an abstract same/different concept, this assumption is no better than using Romanes’ anecdotal method. So instead of assuming that the humans know the same/different concept, we invite them into our laboratory room to experience the same/different task on a touch screen computer. To avoid the humans easily applying a concept they have already mastered, we tell them they will be completing a “touch screen proficiency task.” During the task the humans are rewarded with points on the computer screen for correct same and different responses. After learning the task, nearly all humans were able to perform the same/different task accurately with novel items after experience with only eight specific pictures. Those humans who failed to perform the task accurately with novel pictures reported using elaborate strategies to complete the task, such as strategies related to how pretty they judged the pictures or how firmly they touched the screen, indicating they had over-thought the task and learned an incorrect set of rules. That said, humans can perform the same/different task after experiencing only eight specific pictures. What about monkeys and pigeons?

We have looked at capuchin[10] (a new world monkey) and rhesus[11] (an old world monkey) monkeys’ performance in our same/different task. These are primate species like humans, but we made some changes for nonhumans. Monkeys were tested unrestrained in large metal boxes instead of the laboratory room. Also, we did not use the “touch screen proficiency task” guise to hide the true purpose of the task. Because monkeys are not interested in points, they were rewarded with juice and banana pellets for correct same and different responses. Lastly, the monkeys had to be trained to pay attention to the top picture by requiring them to touch the top picture before the bottom picture and white rectangle appeared. These task modifications (environment, previous knowledge, reinforcement, and attention) did not preclude the monkeys from learning the same/different task with eight specific pictures. However, after learning the task with eight specific pictures, the monkeys did not perform the task accurately with novel pictures. If the experiment stopped here, then we could have concluded a species difference in kind: humans but not monkeys have the mental ability to use the same/different concept. But, as previously mentioned, the experiment does not stop here. Instead, the training set size is increased to include more pictures and subjects are tested with novel pictures after learning the task with larger set sizes. Indeed, monkeys showed better transfer with larger training set sizes, and after training with 128 specific pictures, the monkeys performed as accurately with novel pictures as with their training pictures. This emphasizes the difference between human and monkey mental abilities to use the same/different concept is of “degree and not of kind.”

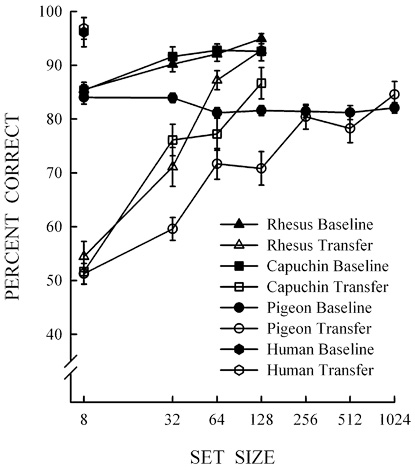

Figure 9.2 - Mean performance and standard errors for baseline and transfer performance at each set size for humans, rhesus monkeys, capuchin monkeys, and pigeons. The set size where baseline and transfer performance are equivalent represents full abstract-concept learning: 8 for humans, 128 for monkeys, 256 for pigeons.

We have also looked at pigeons’ performance in our same/different task,[12] a species distally related to humans by about 300 million years. Again, species differences unrelated to the same/different concept were evident. Pigeons are small and weak compared to humans and monkeys, so they were tested in small wooden boxes. Also, unlike humans and monkeys, pigeons have no fingers; therefore, they cannot touch the screen in the same manner. So instead of requiring a finger touch, the pigeons touched the pictures with their beaks. In addition, because pigeons are not interested in points, banana pellets, or juice, they were rewarded with grain for correct same and different responses. Finally, it was necessary to require the pigeons (like the monkeys) to touch the top picture before the bottom picture and the white square appeared. Just like the monkeys, we found that the pigeons failed to perform accurately with novel pictures after learning the task with eight pictures, but when we progressively increased the training set size, we also found better transfer to novel pictures. For bird-brained pigeons, we had to enlarge the training set size to include 256 specific pictures to show full abstract concept learning. So, humans show full abstract concept learning at 8 pictures, monkeys at 128 pictures, and pigeons at 256 pictures in our task. This represents a difference in degree but not in kind across these different species.

The differences in degree between humans, monkeys, and pigeons in the same/different task are displayed in Figure 9.2. Figure 9.2 shows that the transfer performance increased across set size until full concept learning occurred (humans = 8, monkeys = 128, and pigeons = 256). Importantly, Figure 9.2 shows no difference in kind, as all species eventually performed as accurately with training and novel pictures, demonstrating that they had fully learned the abstract same/different concept. In the future, we hope to expand our research program to investigate abstract-concept learning with a greater number of species.

In conclusion, our research (like that of many others) continues to support Darwin’s notion that animal differences are of degree but not of kind.

Notes

1 - Darwin, C. 1859. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, 1st ed. London: John Murray..

2 - Hodos, W. and C. Campbell. 1969. “Scala Naturae: Why There is No Theory in Comparative Psychology.” Psychological Review 76: 33–50.

3 - Darwin, C. 1871. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

4 - Romanes, G. 1904. Animal Intelligence, 8th ed. London: Kegan Paul, Trench.

5 - Morgan, C. 1894. An Introduction to Comparative Psychology. London: W. Scott.

6 - Thorndike, E. 1911. Animal Intelligence. New York: Macmillan.

7 - Shettleworth, S. 1993. “Where is the Comparison in Comparative Cognition? Alternative Research Programs.” Psychological Science 4: 179–84.

8 - Olson, D. 1991. “Spatial Memory in Clark’s Nutcrackers, Scrub Jays and Pigeons.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes 17: 363–76.

9 - Olson, D., A. Kamil, R. Balda and P. Nims. 1995. “Performance of Four Seed-Caching Corvid Species in Operant Tests of Non-Spatial and Spatial Memory.” Journal of Comparative Psychology 109: 173–81.

10 - Wright, A., J. Rivera, J. Katz and J. Bachevalier. 2003. “Abstract-Concept Learning and List-Memory Processing by Capuchin and Rhesus Monkeys.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes 29: 184–98.

11 - Katz, J., A. Wright and J. Bachevalier. 2002. “Mechanisms of Same/Different Abstract-Concept Learning by Rhesus Monkeys (Macaca mulatta).” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes 28: 358–68.

12 - Katz, J., and A. Wright. 2006. “Same/Different Abstract-Concept Learning by Pigeons.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes 32: 80–86.

- Define learning and then list three examples of learning for three different species.

- By what mechanism did new species replace extinct ones? Be sure to discuss how Darwin could study extinct species?

- The text states that ‘Evolution has a function not a direction.’ What does that mean? Give an example to support your answer.

- With regard to mental facilities, differences between the species are of degree not kind. What might this mean? Give an example to support your answer.

- According to Sara Shettleworth what is wrong with asking: Can nonhuman animals count like humans? Why should comparative psychologists strive not to ask questions like this?

- What is an abstract-concept? Why is same/different an abstract-concept?

- In the same/different task, what is the difference between baseline and transfer performances and how are they used to tell if an abstract-concept has emerged?