2

Darwin as a Geologist

Charles Robert Darwin (1809–82) is widely known as one of the greatest biological scientists of all time. What is not so commonly known is that Darwin was fascinated by the whole of the natural world and was very much interested in both the biotic and physical aspects of nature. For example, his field notes and related writings from the 1831–36 voyage of HMS Beagle are as much about physical features of the Earth and their origins (i.e., geology) as they are about his observations on biology.

Darwin, the son of a practicing physician, was born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England. He attended elementary school in Shrewsbury until 1825, when his father sent him to the University of Edinburgh to study medicine.

Edinburgh (1825–27)

At Edinburgh, Darwin’s eclectic interests in the natural world began to emerge.[1] For example, he developed interests in taxidermy, marine biology, scientific collections, and note-taking about nature. He also had his first encounter with geology, but it did not go well—he took the now-infamous natural history (geology) course from Professor Robert Jameson (1774–1854).[2]

Jameson was the third Regius Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh University, a position that he held for 50 years. During his professorship he became the first strong proponent in England of the Wernerian geological system of thought, or what has been called Neptunism. Neptunism, a 19th-century philosophical approach to geology that lacked empirical data but was strong on emotion, was first developed by Abraham Gottlob Werner (1749–1817), a German mineralogy professor and eminent scholar of that time. Neptunism, which was considered to be appropriately in line with Biblical thinking of the day, held that all the Earth’s rocks were formed in a single violent deluge of hot ocean water that covered the Earth and thus precipitated its mineral crust.[3]

Professor Jameson was noted for his engaging and emotional lectures, which were commonly described as spellbinding for his students. Darwin, however, was horrified by what Jameson said and his disgust with his dogmatic geology professor only grew over the academic term. When Darwin finished the course, he remarked, “I shall never take another geology class in all my life.”[4]

In 1827, Darwin left Edinburgh without finishing his medical program. Darwin said that medicine was not for him. He was not fond of the sight of blood, but he was also appalled by the then-common practices of “body snatching” and murder of paupers that provided significant numbers of cadavers for the medical school at Edinburgh and elsewhere in England.[5]

Cambridge (1827–31)

Darwin’s father, concerned that his son might drift into the life of an idle gentleman, arranged for him to enroll at Christ’s College at Cambridge University to study for the clergy. As at Edinburgh, Darwin’s eclectic interests in natural science emerged again. His interests initially focused on beetle collecting (a common pastime of that era for people interested in natural sciences), nature hikes and observations, scientific debates, and fly fishing. Later, Darwin became interested in travel for scientific investigation, mainly after learned discussions with his biological mentor at Cambridge, John Stevens Henslow (1796–1861), professor of mineralogy and botany. It was Henslow’s particular method of teaching, which employed numerous field excursions and discourses in the field, that so impressed Darwin.[6]

In the summer of 1831, Darwin was introduced to Professor Adam Sedgwick (1785–1873), a clergyman and geologist who held the Woodwardian Chair at Cambridge. Sedgwick was among the most prominent geological scientists in England. His field research was helping to build the concept of geological or stratigraphic systems, which became the basis for the modern geological time scale. Sedgwick took Darwin with him to Wales during the summer of 1831 and gave him an in-depth introduction to field geology. Darwin thus saw an entirely different aspect of geology from the profoundly disappointing course that he had taken at Edinburgh.[7] In an 1831 letter to a hometown friend, Darwin said, “I am now mad about geology.”[8] In another letter he stated, “I am a geologist.”[9]

In 1831, Sedgwick taught Darwin the use of the field clinometer for in situ measurement of what Sedgwick called “dip and strike of strata,” the fundamental type of measurement necessary to discern tectonic movements. Sedgwick also introduced Darwin to geologic rock classification, geologic note-taking, and geologic field interpretations.[10]

Beagle voyage (1831–36)

After finishing his clerical degree at Christ’s College, Cambridge, Darwin applied for the job of naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle. His 1831 application was supported by Professors Henslow, Sedgwick, and others who knew of his abilities as a field naturalist.[11] On the voyage, Darwin took with him Principles of Geology (1830) by Charles Lyell (1797–1875), the first comprehensive textbook of geology ever written. He read this en route (1831–32) to the first stop, the Cape Verde Islands, and afterwards wrote in a letter to Henslow, “It then dawned on me that I might perhaps write a book on the geology of the various countries visited.”[12]

Lyell’s message to Darwin conveyed in Principles was this: The Earth has great antiquity and what we see today is the result of gradual processes acting over long periods of time. Catastrophic processes, such as those held up as explanatory by the Neptunists, are not feasible to explain what we see around us today. Darwin apparently absorbed this message deeply, and his view of the natural world was changed permanently as evidenced in his subsequent writings both geological and biological.[13]

Darwin equipped himself as a geologist for the long voyage and many potential geological discoveries. His geological toolkit included the following: geological hammer, magnifying lens, acid bottle, magnet, blowpipe, goniometer, collecting bags, specimen tags, and several sturdy field notebooks.[14]

At the Beagle’s first stop (January 1832), Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands, Darwin made observations over a 23-day period. His main investigations were not biological, but geological. He was intrigued by a layer of fossil shells situated 45 feet above sea level in the sea cliffs near the Beagle’s anchorage. Darwin noted that the shells were from ancient marine life and that their location so far above the modern sea level showed that sea level must have changed. As suggested by examples discussed in Lyell’s Principles, Darwin interpreted this change as a gradual lowering of sea level over geological time.[15]

At the Beagle’s April 1832 stop at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Darwin trekked inland to collect biological and geological specimens, many of which were soon shipped off to Professor Henslow in England. In August 1832, the Beagle crew began a survey of the Patagonian coast. Darwin collected numerous Patagonian fossils, including remains of giant rodent-like animals, armadillo shells, ground sloths, many species of marine shells, and giant mammal teeth. The larger vertebrate fossils were entirely unknown to science at this time.[16] He sent these specimens to Henslow as well, along with preserved biological specimens (fish, birds, seeds, beetles, snakes, lizards, crustaceans, and plants).[17]

In 1833, after stops at Woolya Cove (Tierra del Fuego), Port Louis (Falkland Islands), and Rio Negro (Argentina), Darwin had amassed a large collection of geological specimens in addition to a trove of biological specimens. He sent these back to England, and in an accompanying July 1833 letter to Henslow he wrote, “I have endeavoured to get specimens of every variety of rock, and have written notes upon all of them.” Among these specimens were samples of “quartz rock” collected on the Falklands. In his field notes, Darwin was careful to describe and sketch the rock outcrops from which he obtained specimens and where the specimens came from within the outcrops, a technique he learned from Sedgwick.[18]

In August 1833, Darwin took an overland excursion into the area of Bahia Banca, Argentina, in the company of a group of local gauchos. During this excursion, he discovered a giant vertebrate fossil, which was later determined to be an extinct ground sloth. He was fascinated by, and took extensive notes on, the simultaneous occurrence of this giant vertebrate fossil and numerous white sea shells, which reminded him of the white shell layer he had studied near Santiago. He speculated on how this fossil might have been transported from land and subsequently entombed within shelly marine sediments. Late in 1833, Darwin sent back to England another shipment of samples, which was heavily weighted toward geological and fossil specimens.[19]

During 1834–35, Darwin conducted geological and biological surveys in parts of Uruguay (Tierra del Fuego) and coastal regions of Chile, including the Chonos Archipelago.[20] According to his field notes, he was developing a particular interest in the Andes Mountains and their origins. On February 20, 1835, as Darwin was visiting Valdivia, Chile, a huge earthquake occurred. Almost every building in Valdivia was destroyed. This caused Darwin to begin thinking about tectonic motions and the origin of mountains.[21] Not long after the earthquake, Darwin was exploring the island of Quiriuina on the Chilean coast and found that the tremor had raised much of the coastline by several feet. He viewed this as direct evidence that the region of the Andes Mountains was rising gradually. To Darwin’s mind, this confirmed the notions expressed in Lyell’s Principles that small, incremental changes in sea-land level over very long time intervals could produce the great mountain ranges of the Earth. This also confirmed to Darwin the great antiquity of the Earth and the long-term nature of geological processes.[22]

Before setting sail for the Galápagos Archipelago in September 1835, Darwin organized several excursions into the Andes Mountains of Chile. He engaged in geological observations, which he recorded in his notebooks, and he collected samples. He began to make geological maps of the basic structure of the Andes, which would form the basis of his later writings and maps concerning the geology of western South America. Darwin also collected water and gas from hot springs of the Andes and sent those samples back to England (along with his rock collections) for further study.[23]

During September and October 1835, the Beagle crew visited several of the Galápagos islands, including Hood, James, Albemarle, Wenman, and Culpepper (now called, respectively, Espaňola, Santiago, Isabela, Wolf, and Darwin). Darwin is noted for his observations on the finches and tortoises of the Galápagos, but he also took extensive notes and made collections of the basaltic volcanic rocks that form the bedrock of all the Galápagos islands.[24] These samples included spectacular examples of porphyritic and vesicular basalts—basalts with large crystals (porphyroblasts) and gas bubble holes—which he collected during an extended stay on James Island.[25]

On the homeward leg of the Beagle voyage (1835–36), Darwin made geological and biological observations in Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia (at Sydney harbor and at Bathurst, New South Wales), Tasmania, Cocos Islands, Mauritius, Simon’s Bay (near Cape Town), South Africa, St. Helena Island, and Ascencion Island. The Beagle arrived home in England with Darwin on board on October 2, 1836.[26]

Darwin’s letters from the Beagle, and in particular the geological comments in those letters, were of keen interest to his friends and mentors back in England.[27] Professor Henslow was so impressed that he compiled these letters into a short book titled Letters on Geology, which was printed in Cambridge “for private distribution” during late 1835.[28] Darwin was unaware of this publishing effort, and when he learned of it from a letter delivered at sea, Darwin wrote to his sister: “But, as the Spaniard says ‘No hay remedio’ ”(there is no remedy for this).[29] The frontispiece of Letters contains the following statement:

The following pages contain Extracts from Letters addressed to Professor Henslow from C. Darwin, Esq. They are printed for distribution among the Members of the Philosophical Society of Cambridge, in consequence of the interest which has been excited by some of the geological notices they contain, and which were read at a Meeting of the Society on the 16th of November 1835.[30]

Post-Beagle, Geological Papers (1836–62)

During the weeks immediately after his return, Darwin met for the first time Charles Lyell, whose book Principles of Geology had so profoundly affected his geological worldview. Lyell helped Darwin find appropriate naturalists with whom Darwin could leave parts of his geological collections.[31] This was an important role for Lyell because this was a time when English museums were being flooded with specimens and objects that were streaming in from colonies all around the world. One who befriended Darwin as a recipient of samples was Richard Owen (1804–92), a curator at the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons (later a professor and superintendent of the Natural History Department of the British Museum). Owen, who is best known for coining the term dinosaur, was keenly interested in Darwin’s geological and fossil specimens and readily took possession of many.[32]

Not long after his return to England, Darwin was inducted as a Fellow of the Geological Society of London, at the time the only learned society for geology in the world. He was recognized for his many discoveries, observations, and collections made during the Beagle voyage.[33] In January 1837, Darwin gave his first post-Beagle paper before the Geological Society. The subject was the gradual rising of the South American continent over long spans of geological time. Darwin told the group he concluded that land masses like South America gradually rise and the nearby ocean floor subsides. Darwin also noted that these gradual changes affected habitats, and that, because of what he had observed in western South America, he felt various species would adapt to the gradual change.[34] Not long after, and simultaneously with his geological writing, Darwin began writing in his famous notebooks about his then-forming ideas on the matter of the gradual transmutation of species.[35]

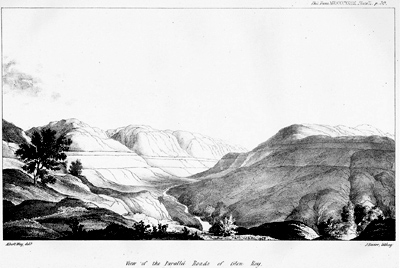

In 1838, Darwin began geological investigations in England. His first and what turned out to be only set of field investigations came during an extended expedition to Glen Roy, Scotland.[36] Darwin went there to investigate the puzzling “parallel roads” phenomenon on Scottish mountain sides (Figure 2.1). The parallel roads looked to Darwin like similar features he had seen in Chile and had interpreted there as ancient shorelines.[37] Darwin’s hypothesis was that the features at Glen Roy were ancient marine shorelines. Darwin laid out his evidence, but his arguments were later convincingly debunked by the famous glacial geologist Louis Agassiz (1807–73).[38] Agassiz showed how these features were instead the result of erosion along a former glacial ice lake shoreline.[39] Later in his career, Darwin would remark that his misinterpretation at Glen Roy was an intellectual setback for him and that his being wrong bothered him through the years.[40]

Figure 2.1 - Sketch of the “parallel roads” of Glen Roy (horizontal lines on the mountains) from Darwin’s 1839 paper in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.[F1] Reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe, ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online.[F2]

By mid-1838, Darwin’s health gradually worsened to the point where he was less able to do field work. His medical problems, including heart palpitations, stomach pains, nausea, headaches, and fevers, may have been caused from bites by tropical insects, but that was not known during his lifetime. Darwin suffered with these discomforts—at times quite debilitating—for the rest of his life.[41] Darwin’s geological field investigations thus came to an end mainly for reasons of health. In early 1839, he married Emma Wedgewood (1808–96) and settled down to a family life in London. His continued intellectual pursuits mainly focused on the interpretation of data he had already collected.[42]

During the next few years, Darwin authored three notable geological books: Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle;[43] The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs;[44] and Geological Observations on South America.[45] From Journal of Researches, here is a sample of Darwin’s geological writing:

I was delayed here five days, and employed myself in examining the geology of the surrounding country, which was very interesting. We here see at the bottom of the cliffs, beds containing sharks’ teeth and sea-shells of extinct species, passing above into an indurated marl, and from that into the red clayey earth of the Pampas, with its calcareous concretions and the bones of terrestrial quadrupeds. This vertical section clearly tells us of a large bay of pure salt-water, gradually encroached upon, and at last converted into the bed of a muddy estuary, into which floating carcasses were swept.[46]

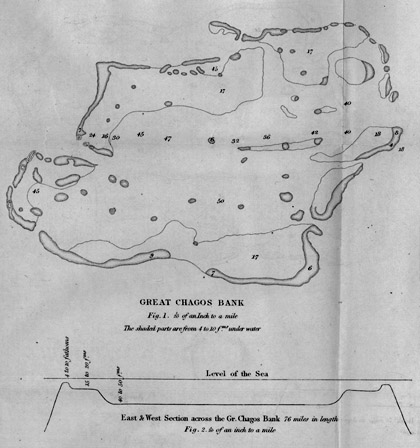

In Coral Reefs (1842), he wrote eloquently on the origin and evolution of these unique features and also included meticulously drawn maps of coral atolls of the Pacific and Indian oceans (Figure 2.2):

A connection . . . between volcanic eruptions and contemporaneous elevations in mass has, I think, been shown to exist, in my work on coral reefs, both from the frequent presence of upraised organic remains, and from the structure of the accompanying reefs.[47]

In South America, Darwin included his now-famous geological cross-section of southern South America (Figure 2.3).[48] This encompassed geologic units such as “granite and andesite,” “mica slate,” “porphyries,” “felspathic clay slate,” “red sandstone,” “calc(areous) slate-rock,” “tuffs and ancient lavas,” and “modern volcanic rocks.” A contemporary published review of South America stated:

It was owing to the observations of Mr. Charles Darwin, on the coast of Patagonia, that geologists were first presented with a series of phenomena of the gradual rising of the land, it then being in a state of repose, for a considerable period, and again rising . . . I immediately saw (how this could apply in other areas).[49]

Figure 2.2 - Example of a detailed sketch, with interpretive cross section (Great Chagos Bank atoll in the Indian Ocean [6o10’N; 72o00’E]) from Darwin’s 1842 Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs.[F3] Reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe, ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online.[F4]

In addition to the four notable geological works mentioned above, during the post-Beagle years Darwin published several other geological papers. These included seven solo-authored geological papers in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society (QJGS). Here is a list of those papers:[50]

- Geological observations on the volcanic islands visited during the voyage of HMS Beagle, together with some brief notices on the geology of Australia and the Cape of Good Hope; being the second part of the Geology of the Voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N., during the years 1832 to 1836 [QJGS, v. 1, p. 556–58, 1845; with a map of the Island of Ascension].

- The structure and distribution of coral reefs; being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N., during the years 1832 to 1836 [QJGS, v. 1, pp. 381–89; 1845].

- An account of the fine dust that often falls on vessels in the Atlantic Ocean [QJGS, v. 2, pp. 26–30; 1846].

- On the geology of the Falkland Islands [QJGS, v. 2, pp. 267–74; 1846].

- On the transportal of erratic boulders from a lower to a higher level [QJGS, v. 4, pp. 315–23; 1848].

- On British Fossil Lepadidae [QJGS, v. 6, pp. 339–40; 1850].

- On the thickness of the Pampean formation, near Buenos Ayres [QJGS, v. 19, pp. 68–71; 1862].

Figure 2.3 - Geological cross-section from the plain of Aconcagua (Argentina) on the west (left) to Uspallata pass (Argentina) on the east—from Darwin’s 1846 Geological Observations on South America.[F5] Reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe, ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online.[F6]

Also during this time, three Darwin-authored papers on geology were published in the Transactions of the Geological Society of London (TGSL).[51]

- On the formation of mould [TGSL, ser. 2, v. 5, pt. 3, pp. 505–09; 1840].

- On the connexion [sic] of certain volcanic phenomena in South America; and on the formation of mountain chains and volcanos [sic], as the effect of the same power by which continents are elevated [TGSL, ser. 2, v. 5, pt. 3, pp. 601–31; 1840].

- On the distribution of the erratic boulders and on the contemporaneous unstratified deposits of South America [TGSL, ser. 2, v. 6, pt. 2, pp. 415–31; 1842].

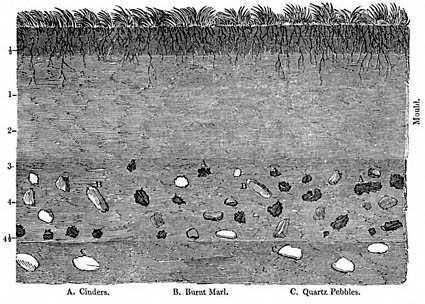

From the time of Darwin’s 1831 declaration “I am a geologist” to the end of the Beagle voyage in 1836, he was quite active physically and intellectually in the realm of geological thinking.[52] As noted above, he continued this geological activity to about 1838, when his ill health essentially retired him from strenuous field studies. In the publications cited above, one can see that after 1838 Darwin relied entirely on either the observations that he made during his voyage or on the Scottish field work of 1838 for his data. Darwin’s 1840 paper on earthworms in soil (what he called “mould”) was based on experiments in his own garden (Figure 2.4). His 1848 paper relied on observations made during the same Scottish field excursions as in his 1839 paper on the “parallel roads.” Darwin’s 1850 paper on Cretaceous barnacles (Lepadidae) appears to have been an entirely laboratory-based investigation of those fossils perhaps involving specimens given to him by others or taken from his Beagle collections (the paper does not say where the specimens came from). Darwin’s last geological journal paper was published in 1862 (as noted above) and was based entirely upon his 1833 field work in Argentina.

Figure 2.4 - Cross-section of a soil layer where Mr. Wedgwood of Staffordshire had placed a layer of cinders, burnt marl, and quartz pebbles (listed in order of increasing density) at the surface in c. 1825, yet in 1837 Darwin observed that earthworms had churned the soil and in so doing these larger components had moved down (scale in inches is at left)—from Darwin’s 1840 paper in the Transactions of the Geological Society. Reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe, ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online.[F7]

One could speculate that if Darwin had not had ill health that his geological field work might have continued and he might have done more in the field of geology. One wonders if he might have considered returning to South America for more field studies. Whether Darwin’s lingering concern about his misinterpretation of the “parallel roads” of Scotland was a factor in his turning away from geological studies in England is unclear.[53] Darwin obviously had more success in writing about South American geology. However, by the time Darwin began publishing post-1838 papers, his mind was turning increasingly toward the origin of species and other biological themes.[54]

Post-Beagle, Biological Papers (1843–71)

By late 1839, Darwin’s first child, a son named William Erasmus Darwin, was born, and Darwin soon felt the need to move out of London to a place with more solitude and open spaces.[55] During the summer of 1842, Darwin’s father purchased a home for Darwin and his family. It was called Down House, located near Kent in the southeast of England. Darwin and family moved there and lived there until his death in 1882.[56]

For Darwin, Down House was a fortress of solitude where he could do his thinking and writing as well as spend time with Emma and his family. Darwin spent progressively more time on his notebook writings about transmutation (change and the origin of species) and on other of his biological papers coming out of his Beagle observations. Of the books written and published during this era in Darwin’s life, the following are important titles:[57]

1843—The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Under the Command of Captain Fitzroy, R.N., during the Years 1832 to 1836 (5 volumes);

1859—On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life;

1871—The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex;

1872—The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

During the period 1875 to 1881, he authored other biological books as well.[58]

His 1859 book, On the Origin of Species, is of course the most famous of all his writings. At the time of its release, a huge chorus was raised both in praise and in criticism for the book and its ideas.[59] Darwin’s geological mentor, Adam Sedgwick (who was among his critics), weighed in on the book, saying in an 1859 letter to Darwin:

If I did not think you a good tempered (and) truth loving man I should not tell you that . . . I have read your book with more pain than pleasure. Parts of it I admired greatly; parts I laughed at till my sides were almost sore; other parts I read with absolute sorrow; because I think them utterly false (and) grievously mischievous— You have deserted—after a start in that tram-road of all solid physical truth—the true method of induction—(and) started up a machinery as wild I think as Bishop Wilkin’s locomotive that was to sail with us to the Moon. Many of your wide conclusions are based upon assumptions which can neither be proved nor disproved. Why then express them in the language & arrangements of philosophical induction?[60]

Nor did Darwin get strong support for Origin of Species from his other mentors. For example, Richard Owen was a strong critic and even Charles Lyell expressed concerns about some of Darwin’s interpretations regarding transmutation.[61] Darwin somehow weathered the storm that this book brought upon him, his family, and supportive colleagues. From Down House, he continued to write biological tomes and papers and ponder nature during long walks in his garden until his death in April 1882.

Conclusion

Darwin as a young scientist appears to have been highly attracted to geological studies and the modes of geological thought expressed by Charles Lyell, whose influential book Darwin digested on the first leg of the Beagle voyage. Darwin embraced geological processes and gradualism and these concepts in turn influenced his thinking about biological change. We should recall that Darwin was inducted into the Geological Society well before he ever aligned with any other scientific group. Even though much of Darwin’s work on the Beagle voyage was geological in nature, Darwin’s geological life changed within a few years of his return to England. This may have been due in parts to the change in his health, the failure of his initial geological work in England to produce sound results, and the rise of his original fascination with the origins of the living world. For whatever reasons, Darwin’s scientific career seems to be divisible into two overlapping phases, the first geological and the second biological. Most people would agree that Darwin is more famous today for his biological work and writings, but we should not forget that Darwin made impressive geological observations and interpretations, especially in South America, and once declared “I am a geologist.”

Notes for Article

1 - Herbert, S. 1986.“Darwin as a Geologist.” Scientific American 254: 94–116; 2005. Charles Darwin, geologist. New York: Cornell University Press.

2 - Ibid.

3 - Leff, D. AboutDarwin.com: Dedicated to the life and times of Charles Darwin. http://www.aboutdarwin.com/.

4 - Herbert, 2005.

5 - Leff; Herbert, 2005.

6 - Ibid.

7 - Ibid.

8 - Ibid.

9 - Ibid.

10 - Ibid.

11 - Herbert, 1986; 2005.

12 - Ibid.

13 - Ibid.

14 - Herbert, 2005.

15 - Leff; Herbert, 2005.

16 - Ibid.

17 - Leff.

18 - Leff; Herbert, 2005.

19 - Ibid.

20 - Leff.

21 - Ibid.

22 - Leff; Herbert, 2005.

23 - Ibid.

24 - Herbert, 2005.

25 - Leff; Herbert, 2005.

26 - Ibid.

27 - Ibid.

28 - Darwin, C. 1835. Letters on geology: Extracts from Letters Addressed to Professor Henslow. Cambridge: J. S. Henslow.

29 - Leff.

30 - Darwin, 1835.

31 - Leff.

32 - Leff; Herbert, 2005.

33 - Ibid.

34 - Ibid.

35 - Ibid.

36 - Rudwick, M. 1974. “Darwin and Glen Roy: a ‘Great Failure’ in Scientific Method?” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 5: 97–185; Leff; Herbert, 2005.

37 - Leff; Herbert, 2005.

38 - Darwin, C. 1839. “Observations on the Parallel Roads of Glen Roy, and of other parts of Lochaber in Scotland, with an attempt to prove that they are of marine origin.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 129: 39–81.

39 - Agassiz, L. 1967. Etudes sur les Glaciers. In Studies on Glaciers, Preceded by the Discourse of Neuchâtel. trans. A. Carozzi. New York: Hafner.

40 - Leff; Herbert, 2005.

41 - Leff.

42 - Ibid.

43 - Darwin, C. 1839. Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World. London: John Murray.

44 - Darwin, C. 1842. The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs: Being the First Part of the Geology of the Voyage of the Beagle, Under the Command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. During the Years 1832 to 1836. London: Smith Elder and Co.

45 - Darwin, C. 1846. Geological Observations on South America. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

46 - Darwin, 1839.

47 - Darwin, 1842.

48 - Darwin, 1846.

49 - Leff.

50 - van Wyhe, J. The complete works of Charles Darwin online. http://darwin-online.org.uk/.

51 - Leff.

52 - Herbert, 1986; 2005; Leff.

53 - Rudwick, 1974.

54 - Leff.

55 - Ibid.

56 - Ibid.

57 - Ibid.

58 - Ibid.

59 - Ibid.

60 - Ibid.

61 - Ibid.

Notes for Figures

F1 - Darwin, C. 1839. “Observations on the Parallel Roads of Glen Roy, and of other parts of Lochaber in Scotland, with an attempt to prove that they are of marine origin.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 129: 39–81.

F2 - van Wyhe, J. The complete works of Charles Darwin online. http://darwin-online.org.uk/.

F3 - Darwin, C. 1842. The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs: Being the First Part of the Geology of the Voyage of the Beagle, Under the Command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. During the Years 1832 to 1836. London: Smith Elder and Co.

F4 - Van Wyhe.

F5 - Darwin, C. 1846. Geological Observations on South America. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

F6 - Van Wyhe.

F7 - Ibid.

- What influence did Darwin’s Cambridge professors have upon his interests in geological studies?

- What was the influence of Lyell’s Principles of Geology upon Darwin’s thinking about the natural world, both during his Beagle voyage and thereafter?

- What was Darwin’s mistake in his interpretation of the “parallel roads” in Scotland? What lasting effect did this mistake appear to have on Darwin’s career?

- What were the many types of observations that Darwin made on the geology of South America that were the basis for his writing a book on the subject?

- What were the many factors involved in Darwin’s transition from geological field work to more contemplative, scholarly studies based at his home?