3

Darwin and Collections

Charles Darwin was a collector. From the time of his childhood to his old age, Darwin made collections of biological and geological materials. Even his pet pigeons found their way into museums as stuffed specimens or skeletons. This was not unusual as the natural sciences at the time were largely collection-based. The late 1700s through around 1900 saw the formation of the world’s greatest natural history museums as scientists searched the world for specimens. It was deemed so important a task that even the British Navy was enlisted, with a ship’s surgeon often serving as the ship’s naturalist, and even some of the captains, like Captain Robert M. Fitzroy, also collecting specimens from their journeys.[1]

Darwin helped shape this grand age of natural history. Natural history had been around as a science since the Greeks, and Aristotle is often regarded as its founder, but natural history certainly goes further back than that. We are products of our environment, and have been learning about it for our entire existence. We give names to those things that are important to us, and we learn how they live so that we might use them as food or other products.

Despite its importance to the Greeks, natural history wilted in Europe in the Middle Ages. However, it flourished in the Arabic world. Even natural selection may have been presaged by the Arabic author Al-Jahiz (Amr ibn Bahr al-Kinani al-Fuqaimi al-Basri al-Jahiz, 781–868),[2] although this may be overstated.[3] Al-Jahiz in his Book of Animals stated: “Animals engage in a struggle for existence; for resources, to avoid being eaten and to breed. Environmental factors influence organisms to develop new characteristics to ensure survival, thus transforming into new species. Animals that survive to breed can pass on their successful characteristics to offspring.”[4]

In Europe, natural history mainly muddled along through the Middle Ages following largely from Aristotle, but the explosion of new species being discovered with the advent of transoceanic voyages demanded that rules of classification be developed. The Swedish botanist Carl Linne (Carolus Linneaus, 1707–78) gave us the Linnean Classification scheme starting with Systema Naturae,[5] and, most importantly, he gave us the binomial system in which species are recognized as a combination of a genus and a specific epithet, and this ushered in the modern taxonomic era into which Darwin was born.

Pedigree

Charles Darwin was the son of Robert Darwin (1766–1848) and grandson of Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802). Erasmus was a physician, poet, and natural philosopher, among many other attributes. In the popular The Loves of Plants, he explains the Linnean Classification scheme, and in Zoönomia, he presaged the views of Lamarck that animals could evolve by selective use and disuse of characters and that these traits could be passed on to their offspring.[6]

Robert Waring Darwin also became a physician, but he was not a naturalist. In many ways he was the exact opposite of Charles. He was a successful student, doctor,[7] and financier.[8] He was also a very large man who stopped weighing himself when he was 24 stone (about 336 pounds), whereas Charles was very athletic. Both Robert and Erasmus were among the liberal elite and known for their support of the abolition of slavery. Robert was a freethinker[9] who believed that science and reason—not the supernatural—should govern life. Clearly, Robert’s belief in free thought affected Charles’s later use of science and reason to explain how life evolved.[10]

Charles’s mother, Susannah Wedgwood, was a Unitarian, and Darwin’s first school was a day school run by the Unitarians,[11] who are also known for non-dogmatic thinking. This pedigree of freethinkers, liberals, and scientists likely allowed Darwin to help reform a largely observational natural history into a true science.

Schooling

Charles was sent in 1825, at the age of 16, to the medical school at the University of Edinburgh. His father wished him to attend that school because he had and because it had a radical faculty in a relatively liberal city— in other words, people more like him. Charles hated classes, even zoology, but he and his brother (Erasmus) checked out more books from the library than all other students combined, so he wasn’t wasting his time. He hated the two surgeries he witnessed, one done on a child without anesthesia. He could not stand the sight of blood and had ethical problems with how human cadavers came to be dissected at the school. Clearly he was not meant to be a doctor.

In that first year in school, he learned some taxidermy, which would be essential for his future work. On January 29, 1826, he wrote to his sister about his teacher, John Edmonstone, a freed slave from British Guiana (now Guyana):[12]

I am going to learn to stuff birds, from a blackamoor I believe an old servant of Dr. Duncan: it has the recommendation of cheapness, if it has nothing else, as he only charges one guinea, for an hour every day for two months.

Edmonstone had learned taxidermy from the famed taxidermist Charles Waterton, and he taught Charles not only how to stuff birds but also about life in the jungle and about life as a slave. These discussions made Charles long for trips into the jungle.[13] Even more important, his discussions with Edmonstone, combined with the abolitionist beliefs passed down through his family, likely were responsible for Charles’s early thoughts on the common descent of humans. In other words, learning some of the basic techniques of taxonomy and the building of collections were instrumental in the formation of one of Darwin’s great ideas, that of the common descent of all species in general and our own in particular.

In Edinburgh, Darwin also learned a lot from Robert Grant, an early evolutionist and a fan of Charles’s grandfather. Charles became one of Grant’s favorite students, in part because of his ancestry. Grant taught Charles about marine invertebrates, which would become a lifelong fascination. Grant also taught Charles about the concept of homology.[14] Homology can be defined today as the shared evolutionary origin of a structure. In evolutionary biology, homology refers to characteristics that are similar because of shared ancestry, though the characteristic might not be used in the same way. For example the bones in the arm of a human and that of a bird are homologous, despite the fact that birds and humans use those bones quite differently. However, the presence of homologous structures can indicate a pattern of common descent.

After two years, it was clear that Darwin was failing as a student. He didn’t care for his lectures and was only interested in natural history. His father famously scolded him by saying, “You care for nothing but shooting, dogs and rat catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family.”[15] Even today, this is often the belief of parents whose children wish to go into the natural sciences, and many of us can relate similar if not quite as extreme stories about our own parents.

Robert took Charles out of the University of Edinburgh and enrolled him at Christ’s College, Cambridge. Now Charles was to become a country parson after completing his degree in divinity. That clearly never happened, but Darwin was a relatively good student at Cambridge, though he was still bored by his classes—he frequently did not attend them—and he still cared more for natural history.

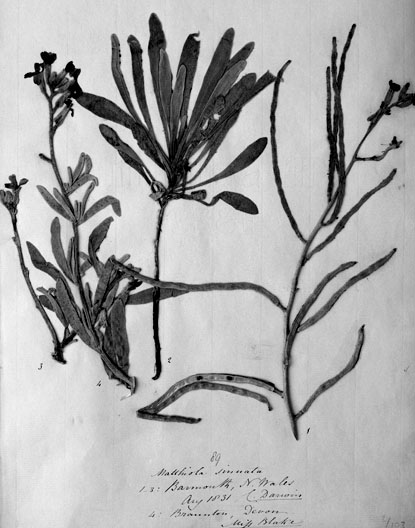

At Cambridge, Charles met the botanist John S. Henslow. He and Henslow became so inseparable that people came to refer to Charles as “The Man Who Walks with Henslow.”[16] Henslow was unique among botanists at the time in that he arranged his herbarium by collation.[17] This means that he placed several specimens on one herbarium sheet to show the range of variation of a species. This was a unique way of looking at things because variation was often not referred to when a species was defined solely by the type specimen (the typological species concept). Thus, Henslow introduced Charles to variation. Charles also contributed to the Henslow Herbarium, and his earliest known herbarium specimen (1831) is that of the sea stock (Matthiola sinuata; Figure 3.1).[18]

Figure 3.1 - Collated herbarium sheet of three specimens of Sea Stock, Matthiola sinuate, collected by Charles Darwin. From Kohn, et al. (2005).

While at Cambridge, Charles also renewed his interest in collecting beetles. His prowess and interest in collecting was well-known by his peers. He got into a heated rivalry with fellow student Charles Babbington, who was often referred to by the moniker “Beetles.” Another student, Albert Way, drew a cartoon of Charles hunting for beetles while riding a very large one. Of this period, Darwin writes about one particular episode that tells of the joys, excitement, and frustration of a collector.

One day, on tearing off some old bark, I saw two rare beetles, and seized one in each hand; then I saw a third and new kind, which I could not bear to lose, so that I popped the one which I held in my right hand into my mouth. Alas! It ejected some intensely acrid fluid, which burnt my tongue so that I was forced to spit the beetle out, which was lost, as was the third one.[19]

Charles graduated from Christ’s College in 1831, 10th of 171 students. He still did not know what to do with his life, but he was encouraged by Henslow to take a trip to North Wales with the geologist Adam Sedgwick. It was on this trip that he learned most of his skills in geology. It was also during this trip that Captain Robert Fitzroy once again came looking to Henslow for a traveling companion on what was supposed to be a two-year voyage on HMS Beagle. Henslow had a young family and had previously suggested his brother-in-law, Leonard Jenyns, as a voyager. Jenyns backed out, and this time Henslow enthusiastically suggested Charles Darwin.[20]

The position was unpaid. Contrary to common lore, Darwin was not the ship’s naturalist, which was a title held by the ship’s surgeon. Instead, his position was ship’s gentleman, and he was basically hired on to be Captain Fitzroy’s friend. He took the position because he could do natural history.[21] Throughout what would become a five-year voyage, Charles would send specimens back to Henslow and Henslow would forward them to experts for examination.

The primary mission of the HMS Beagle was to map southern South America, but the voyage would include many stops along the way, each providing a different habitat for Charles to explore. It was South America where the Beagle spent most of its time, and it was South America that really began to reveal the story of evolution to Charles.

His first stop in South America was Bahia, Brazil, and the majesty of the neotropical rainforest was immediately apparent to him.

Delight itself, however, is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who for the first time has wandered by himself in a Brazilian forest. The elegance of the grasses, the novelty of the parasitical plants, the beauty of the flowers, the glossy green of the foliage, but above all the general luxuriance of the vegetation, filled me with admiration.[22]

His first real taxonomic work was in the Atlantic Coastal rainforest of Rio de Janeiro, where he spent three months. Among his discoveries were terrestrial flatworms, many of which he would eventually describe. Darwin speaks of the rain forest with the reverence of a natural historian when he comes to the realization that almost all was new, and all was of great interest. To a person with broad interests, the rain forest presents a unique challenge of what to collect.

In England any person fond of natural history enjoys in his walks a great advantage, by always having something to attract his attention; but in these fertile climates, teeming with life, the attractions are so numerous, that he is scarcely able to walk at all.[23]

Most of the time that Charles spent in South America was based out of Uruguay. He spent two years exploring Uruguay and Argentina, collecting specimens, and observing the life history of plants and animals. His collections from Patagonia famously included some very important fossils (particularly mammals), such as the first fossil of the South American ungulate Toxodon platensis.[24]

While all of his collections were certainly important in the formation of Darwin’s ideas, none are more synonymous with Charles Darwin than his collections from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. The Beagle arrived on Chatham Island (now Isla San Cristóbal), on September 17, 1835. Apparently the first specimen he procured was a specimen of the jewel moray. Although the original specimen is lost, the species would be described from his other specimens as Muraena lentiginosa.[25] He also observed the iguanas of the Galapagos and wrote of the terrestrial one in not so glowing, but incredibly accurate, prose.

. . . ugly animals, of a yellowish orange beneath, and of a brownish-red colour above: from their low facial angle they have a singularly stupid appearance.[26]

Although Darwin provided a nice picture of the plants and animals of the Galapagos, it was the finches of the islands that came to bear his name. The importance of these finches to Darwin’s thinking was probably pretty limited. He made a couple of crucial mistakes that were later pointed out to him by the ornithologist John Gould. First, he thought that the species were from different groups and not descended from a common ancestor. Second, he committed one of the most grievous of errors for a collector: he didn’t bother to label the island of origin for many of the specimens.[27] Much of what Gould was able to determine of the so-called Darwin’s finches was based on specimens that were collected by Robert Fitzroy, or on localities divined by Darwin trying to fill in gaps of his memories with interviews with shipmates who might have been with him when he collected.[28] Darwin was sufficiently humbled by his lack of foresight.

It never occurred to me, that the productions of islands only a few miles apart, and placed under the same physical conditions, would be dissimilar. I therefore did not attempt to make a series of specimens from the separate islands. It is the fate of every voyager, when he has just discovered what object in any place is more particularly worthy of his attention, to be hurried from it.[29]

Although Darwin’s finches were of dubious importance to Darwin’s ideas, the mockingbirds of the Galapagos were likely a great influence. He recognized that there were different species of mockingbird on the large islands of the Galapagos, with these species also occurring on the smaller islands around the large ones. Eventually, a fourth species would be discovered. Darwin immediately recognized the significance of these birds, and it was clear to him that the amount of variation of mockingbirds on the islands was greater than what he had observed in South America, and that the similarity of the mockingbirds in the Galapagos suggested a common ancestor that had come from the mainland. He wrote:

These birds agree in general plumage, structure, and habits; so that the different species replace each other in the economy of the different islands. These species are not characterized by the markings on the plumage alone, but likewise by the size and form of the bill, and other differences.[30]

He was noting local adaptation not just in color but also in form. To show the use of his collections even today, the Museum of Natural History, London, produced a film on the specimens.[31] Although mockingbirds were common when Charles visited the Galapagos, the species on Isla Floreana was extirpated by 1880.[32] Mockingbirds were present on islands around Floreana, but to determine if they were the same species, tissue samples were taken from Charles’s specimens for genetic analysis, and compared with the DNA of the other mockingbirds. Certainly Charles could not have known that his specimens would ever make such an important contribution because he knew nothing of DNA. This story suggests the importance of collections: we never know what the specimens we collect and deposit in museums will be used for in the future, and sometimes we can’t even hazard a guess.

Back in England

Early in the voyage (June 1833), Darwin wrote, “It is a grand spectacle to see all nature thus raging; but Heaven knows every one in the Beagle has seen enough in this one summer to last them their natural lives.”[33] Although Darwin would continue to make contributions to collections, his importance as a collector plummeted when he returned to the family home, “The Mount,” on October 5, 1836. He was unannounced and his father and sisters were just sitting down to breakfast. Robert would eventually write, “Why the shape of his head is quite altered.”[34] The person that Robert had chastened as someone who would bring shame to his family had matured and found his direction.

The idea of marriage soon came to Darwin’s mind, and he approached finding a wife like collecting any other specimen. He wrote to his friend C. T. Whitley, May 8, 1838, as he was working on his contribution to Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle and editing The Zoology of the Voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle:[35]

Of the future I know nothing I never look further ahead than two or three Chapters—for my life is now measured by volume, chapters & sheets & has little to do with the sun— As for a wife, that most interesting specimen in the whole series of vertebrate animals, Providence only know whether I shall ever capture one or be able to feed her if caught.

Infamously, Darwin would scribble in his notebook the pros and cons of marriage. Under “Marry,” he wrote “constant companion, (friend in old age) . . . better than a dog anyhow.”[36] He concluded “Marry, Marry, Marry.” He married his first cousin, Emma Wedgwood, on January 29, 1839.

Charles had returned to England with some degree of fame and notoriety because Henslow had sent specimens to experts for identification and to describe new species. Darwin edited The Zoology of the Voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle, with five parts published between 1838 and 1843:

- I - Fossil Mammalia by R. Owen, 1838–40 (preface and geological introduction by Darwin)

- II - Mammalia by G. R. Waterhouse, 1838–39 (geographical introduction and a notice of their habits and ranges by Darwin)

- III - Birds by J. Gould [and G. R. Gray], 1838–41

- IV - Fish by L. Jenyns, 1840–42

- V - Reptiles [and Amphibia] by T. Bell, 1842–43

The specimens obtained by Darwin were remarkable, and included a species named Rhea darwinii by Gould (Darwin’s or lesser rhea, later synonymized with Rhea pennata and placed in the genus Pterocnemia). The holotype of R. darwinii has an interesting story. Darwin had heard of this smaller species of rhea but had been unsuccessful in finding a specimen. Early in January 1833, the Beagle’s artist, Conrad Martens, shot a rhea that they thought was a juvenile and they proceeded to eat it. Darwin then realized that it was not a juvenile but a specimen of the elusive smaller rhea. He managed to preserve the head, neck, legs, one wing, and some large feathers. The resulting holotype of Rhea darwinii was a near complete composite of several specimens.[37]

Darwin also collected plants, and perhaps it was plants that led Darwin to one of his most important colleagues, John D. Hooker, who would become the director of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew. Hooker read proofs of Darwin’s Beagle accounts while on a similar voyage (1839–43), and was approached by Darwin upon his return to describe the Galapagos plant specimens. It was Hooker who probably first heard Darwin’s evolutionary ideas, and Hooker who pushed Darwin to work on his most significant taxonomic project, a project that would shape the future of taxonomy and provide a forum for Darwin’s developing evolutionary ideas. Charles wrote Hooker September 8, 1844, and told him of the ideas that he has been forming to explain the patterns of distributions that he had observed of species:[38]

The conclusion, which I have come at is, that those areas, in which species are most numerous, have oftenest been divided & isolated from other areas, united & again divided;—a process implying antiquity & some changes in the external conditions. This will justly sound very hypothetical.

I cannot give my reasons in detail: but the most general conclusion, which the geographical distribution of all organic beings, appears to me to indicate, is that isolation is the chief concomitant or cause of the appearance of new forms (I well know there are some staring exceptions) . . .

What Darwin is stating is that vicariance (geographic isolation) leads to speciation. This is now accepted as the main means of speciation, and it would have been considered heretical at the time. Hooker was skeptical, replying, “Nothing will give me so much pleasure as to get grounds for your reasonings & to carry out your theory of isolation.”[39] Darwin would pass ideas off to Hooker and get most of his botanical information from him. Hooker, along with Thomas Henry Huxley, would come to the defense of Darwin at the great Oxford Evolution Debate, but before that, Hooker is responsible for sending Darwin down his eight-year foray into the taxonomy of barnacles.

By 1846, Darwin has cataloged all of his specimens except one, a barnacle. He wrote to Hooker, October 2, 1846, “Are you a good hand at inventing names: I have a quite new & curious genus of barnacle, which I want to name, & how to invent a name completely puzzles me.”[40] It was an innocent beginning. Hooker’s basic response was that he needed to complete the description of this species because Charles could not really talk about his ideas on evolution without doing some taxonomy. Hooker did not expect this to take eight years, and neither did Darwin, but taxonomy projects are like that. Once people heard that Darwin was working on barnacles, museums and collectors began sending him their specimens, and the project, like all good taxonomy, snowballed. In the end, Darwin published two monographs on the Cirripedia.[41] The taxonomy was much more akin to what taxonomists do today than anything that came before, and it hearkened back to the love of invertebrates and homology that Robert Grant had inspired in him at the University of Edinburgh. Darwin sought homologies to define his species, and the taxonomy was built around his idea of descent with modification.

Conclusion

Darwin now had all of the information he would need and all of the techniques that he required to finish Origin of Species. Origin is a book built on collections, and another collector, Alfred Russel Wallace, who had developed similar ideas as he had been working essentially as a professional collector, spurred him into publication. Darwin learned what he needed to know based on his experiences in the field and with specimens that he and others had collected. I, at least, see Origin as a culmination of the old school of taxonomy and collection’s science. Darwin transformed taxonomy with his publication as he did all other fields of biology. Many fields of biology and geology can claim Charles, but more so than any other field of biology, we taxonomists can claim him as one of our own.

Darwin’s work also illustrates the essential importance of fieldwork and collections-based science. Without his experiences in the field, and without careful examination of specimens, Darwin would not have been able to see the truths of the universe that he unveiled in Origin. Today, collections-based science is experiencing a Renaissance and perhaps its death sentence at the same time. Many universities are getting rid of their collections, and the collections are either being destroyed or being sent to large centers like the Smithsonian Institution, but it is the universities that are in charge of teaching the next generation of scientists. Darwin learned his love of his science from his professors, and if we continue to whittle away at the university collections, students studying natural history will also disappear. Large museums are important, but they cannot teach university students what they need to know.

Luckily, Alabama is far ahead of many regions. We still have excellent training of students in natural history, and the state supports two strong university museums at Auburn University and the University of Alabama. Perhaps it will be here that the next Darwin will be molded.

After Darwin’s return from the voyage of the Beagle, he no longer was a significant contributor to collections; however, he did not stop. He continued to prepare specimens, particularly of his pets. Darwin had a fondness for fancy pigeons, with their strange morphology taking up a large chunk of Origin. As those birds aged and died, Darwin would skin them or skeletonize them, and even his pets now live on. Darwin lives on in his collections. Authors will cite the species he described for centuries, so he would have achieved some degree of immortality even if he had just been a taxonomist. Perhaps we would not be dedicating symposia to him or producing Hollywood movies about his life, but his work would still live on.

On Being Darwin

In the fall of 2008, James Bradley at Auburn University asked me if I would be interested in dressing as Darwin for the celebratory events in 2009. I have a passing resemblance with Charles, with a distinct brow ridge and what is left of my hair a sandy brown, but at 5'5" I was much shorter, and my weight tended more towards Robert than Charles, who had a relatively athletic build. I thought it would be fun, and I agreed, but I didn’t want to be the long-white-haired, grizzled Darwin. Being only 39, I didn’t think I could pull it off. Besides, it was a celebration of Darwin’s birth and the publication of Origin, and so the Auburn University Theater Department developed a period-accurate costume of Darwin from the time of the publication of Origin.

As I sat and watched the talks dressed as Darwin, I sometimes felt myself being more than an actor, and it seemed that when speakers talked of Darwin’s discoveries, they were talking about me. I have come to realize that all biologists are like this. Darwin revolutionized biology, and nearly every biologist sees something in themselves of Darwin. It is easy to put on the costume and become one with the role.

Recently, having lost a lot of weight and being more in line with Charles’s build, and needing to return finally my outfit, I decided to take Charles out for a walk. It was Halloween in downtown Auburn, so my appearance wouldn’t be that unusual. During that walk, one woman asked if I was Samuel Adams. I told her I was Darwin, and she had no idea who Darwin was. I said “evolution,” and she still had no idea. Exasperated, I said, “He was a biologist.” What it taught me was that we still have a lot to do in teaching evolution, and there are a lot of people who still don’t know what the science is. As we look at the debate that evolution still produces, we have to realize that the debate exists because education of the public is incomplete.

Notes

1 - Cock, R. 2005. Scientific Servicemen in the Royal Navy and the Professionalisation of Science 1816–1855. In Science And Beliefs: From Natural Philosophy To Natural Science, 1700–1900. eds. D. Knight and M. Eddy. Aldershot: Ashgate, 95–111; Steinheimer, F. 2004. “Charles Darwin’s Bird Collection and Ornithological Knowledge during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, 1831–1836.” Journal of Ornithology 145: 300–20.

2 - Zirkle, C. 1941. “Natural Selection before the Origin of Species.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 84:71–123; Bayrakdar, M. 1983. “Al-Jahiz and the Rise of Biological Evolutionism.” Islamic Quarterly 21:149–55.

3 - Egerton, F. 2002. “A History of the Ecological Sciences; Arabic Language Science—Origins and Zoological.” Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 83: 142–46.

4 - Bayrakdar, 1983. Quoted in Bayrakdar (1983).

5 - Linnaeus, C. 1735. Systema Naturae. Leiden: Th. Haak.

6 - Darwin, E. 1789. The Botanic Garden, Part II, The Loves of the Plants. London: J. Johnson; 1792. Zoönomia; or, The Laws of Organic Life. London: J. Johnson.

7 - King-Hele, D. 1977. Doctor of Revolution: The Life and Genius of Erasmus Darwin. London: Faber & Faber.

8 - Browne, J. 1996. Voyaging. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

9 - Desmond, A. and J. Moore. 1991. Darwin. London: Penguin; Phipps, W. 2002. Darwin’s Religious Odyssey. New York; Trinity Press International.

10 - Desmond and Moore, 1991.

11 - Phipps, 2002.

12 - Burkhart, F. and S. Smith, eds. 1985. The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, Volume 1, 1821–1836. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press.

13 - Darwin, C. 1887. The Autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882 Wih the Original Ommissions Restored. Edited and with Appendix and Notes by his Granddaughter Nora Barlow. ed. N. Barlow. London: Collins, 1958.

14 - Ibid.

15 - Darwin, F., ed. 1887. The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, including an Autobiographical Chapter, vol. 1. London: John Murray, 32.

16 - Darwin, 1887.

17 - Kohn, D., G. Murrell, J. Parker and M. Whitehorn. 2005. “How Henslow taught Darwin.” Nature 436: 643–45.

18 - Ibid.

19 - Darwin, 1887.

20 - Browne, 1996.

21 - Ibid.

22 - Darwin, C. 1839. Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle Between the Years 1826 and 1836, Describing their Examination of the Southern Shores of South America, and the Beagle’s Circumnavigation of the Globe. Journal and Remarks, 1832–1836. London: Henry Colburn, 11.

23 - Darwin, 1839.

24 - Owen, R. 1840. The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. Part 1; Fossil Mammalia. ed. C. Darwin. London: Henry Colburn.

25 - Jenyns, 1842.

26 - Darwin, C. 1845. Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, 2nd ed. London: John Murray, 388.

27 - Darwin, 1845; Sulloway, F. 1982. “Darwin and his Finches: the Evolution of a Legend.” Journal of the History of Biology 15:1–53; Steinheimer, F. 2004. “Charles Darwin’s Bird Collection and Ornithological Knowledge during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, 1831–1836.” Journal of Ornithology 145: 300–20.

28 - Sulloway, 1982.

29 - Darwin, 1839.

30 - Darwin, 1839.

31 - Natural History Museum. Darwin’s Mockingbirds Knock Finches off Perch. http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/news/2008/november/darwins-mockingbirds-knock-finches-off-perch23090.html.

32 - Curry, R. 1986. “Whatever Happened to the Floreana Mockingbird?” Noticias de Galápagos 43:13–15; Grant, P. , R. Curry, and B. Grant. 2000. “A Remnant Population of the Floreana Mockingbird on Champion Island, Galápagos.” Biology Conservation 92: 285–90.

33 - Darwin, 1887.

34 - Darwin, 1887.

35 - Burkhart, F. and S. Smith, eds. 1986. The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol 2: 1837–1843. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

36 - Darwin, 1887.

37 - Steinheimer, 2004.

38 - Burkhart, F. and S. Smith, eds. 1987. The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, Volume 3, 1844–1846. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

39 - Ibid.

40 - Ibid.

41 - Darwin, 1851, 1854.