4

Darwin, Wallace, and Malthus

Charles Darwin (1809–82), Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913), and Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) had much in common. They were English, scientists, and lived in the 19th century (though Malthus’s important work was completed late in the 18th century). Nonetheless, they led very different lives. Though his five-year voyage of discovery on the sailing ship HMS Beagle brought him fame and provided inspiration for his thinking on natural selection, Darwin suffered poor health for much of his life and remained close to his home near London. In contrast, Wallace spent many years trekking through exotic parts of the world tirelessly collecting specimens. Wallace devised a theory of natural selection independently of Darwin, but he was destined to remain in the shadow of Darwin’s fame and distinction. Though nearly as famed as Darwin, but quite possibly more controversial, Malthus lived the quiet life of a college professor at the East India College in southeast England. In much the same way that the lives of these three men shared a great deal and differed a great deal, their ideas came together then diverged in ways that are fruitful and illuminating.

Convergent Thinking

Everyone knows of Charles Darwin, the great scientist whose theories of evolution transformed biology and lit a firestorm of controversy that today continues burning vigorously. Many also know that his thinking was introduced to the world in his astonishing work, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, which appeared in 1859. Fewer are aware that he began devising his revolutionary ideas more than 20 years earlier but was reluctant to publish them because he understood that they would prompt intense controversy. Even fewer are likely aware of the source of Darwin’s inspiration. In his autobiography, Darwin described the crucial moment:

In October 1838, that is, fifteen months after I had begun my systematic inquiry, I happened to read for amusement Malthus on Population, and being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence which everywhere goes on from long-continued observation of the habits of animals and plants, it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here, then, I had at last got a theory by which to work.[1]

Malthus, in other words, supplied the threads that allowed Darwin to stitch his observations into a theory of natural selection. Though Darwin is commonly identified with the concept of evolution, that idea was widely understood in his day. Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus, was well aware of species change. But no one understood how the variation of species took place or why species varied. Darwin’s theory of natural selection filled that void, and it remains his great achievement.[2]

Many readers also know of Alfred Russel Wallace. He was Darwin’s younger contemporary, born in 1823, 14 years after Darwin. Even before Origin of Species appeared, Darwin was a towering figure in 19th-century science. The journals Darwin kept while voyaging on the Beagle were published before he returned to England, and they made his fame long before he again set foot ashore his native land. So, like many educated people, Wallace knew of Darwin and shared their high regard for his work. Though Darwin spent only a few years collecting specimens abroad, Wallace travelled for many years in remote and primitive locations, chasing down tens of thousands insects, birds, and plants.[3] In 1858 while recuperating from a bout of malaria on the island of Ternate, presently part of Indonesia, Wallace was struck by the following thought:

One day something brought to my recollection Malthus’s “Principles of Population,” which I had read twelve years before. I thought of his clear exposition of “the positive checks to increase”—disease, accidents, war, and famine—which keep down the population of the savage races to so much lower an average than that of more civilized peoples. It then occurred to me that these causes or their equivalents are continually acting in the case of animals also; and as animals usually breed much more rapidly than does mankind, the destruction every year from these causes must be enormous in order to keep down the numbers of each species, since they evidently do not increase regularly from year to year, as otherwise the world would long ago have been densely crowded with those that breed most quickly. Vaguely thinking over the enormous and constant destruction which this implied, it occurred to me to ask the question, Why do some die and some live? And the answer was clearly, that on the whole the best fitted live. From the effects of disease the most healthy escaped; from enemies, the strongest, the swiftest, or the most cunning; from famine, the best hunters or those with the best digestion; and so on. Then it suddenly flashed upon me that this self-acting process would necessarily improve the race, because in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain—that is, the fittest would survive.[4]

Excited by the implications of this insight, Wallace set to work on a paper in which he laid out his new theory of natural selection.[5] Completely unaware of Darwin’s convergent thinking on this matter, Wallace sent him a copy for his examination. As is widely known, Wallace’s article dissolved Darwin’s fears and shocked him into rushing Origin of Species into print.[6]

Malthus’s theory of population provided both Darwin and Wallace with the resource they needed to pull together their observations of species change and give them an explanation. It is entirely possible that one or both of them would have arrived at the principles of natural selection without Malthus’s prompting. As it happened, Malthus provided each with the key he required.

Thomas Malthus died in 1834, barely 12 years after Wallace was born. Though trained as a minister, he spent most of his life teaching political economy at the East India College in Hertfordshire, England.[7] Kind and gracious in person, he was much beloved and highly respected by his contemporaries.[8] Malthus began developing his thoughts after an argument with his father on the question of whether human progress is possible. His father, an enthusiastic partisan of the Enlightenment, was confident of the possibility of human progress.[9] Like many sons, Thomas was keen to prove his father wrong. But, unlike many father-son arguments, Thomas spent the rest of his life working out the implications of his thinking and gathering evidence to support it. His theory of population initially appeared in 1798. As Malthus elaborated his views and accumulated data to support his theory, his early, brief work grew into a substantial book. It became one of the most widely read and influential works of the 19th century.[10] It appeared in many editions and can easily be found in print today. Like other educated people of their day, both Darwin and Wallace were well acquainted with Malthus’s thinking.

The key Malthus provided to Darwin and Wallace is known informally as Malthus’s “Dismal Theorem.” Malthus described it early in An Essay on the Principle of Population. As he put it,

I think I may fairly make two postula. First, that food is necessary to the existence of man. Secondly, that the passion between the sexes is necessary and will remain nearly in its present state. These two laws, ever since we have had any knowledge of mankind, appear to have been fixed laws of our nature, and, as we have not hitherto seen any alteration of them, we have no right to conclude that they will ever cease to be what they now are, without an immediate act of power in that Being who first arranged a system of the universe, and for the advantage of his creatures, still executes, according to fixed laws, all its various operations . . .

Assuming my postulates as granted, I say, that the power of population is indefinitely greater than the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man. Population, when unchecked, increases in geometrical ratio. Substance increases only in arithmetical ratio. A slight acquaintance with numbers will shew the immensity of the first power in comparison to the second.[11]

As is apparent from the above passage, Malthus provided Darwin and Wallace with two essential ideas. One is that there is an upper limit to the population of any species. The second is the notion of a force, sexual passion, that propels the members of a species to reproduce until their numbers exceed that limit. Taken together, these two ideas gave Darwin and Wallace the intellectual framework they needed to construct the principle of natural selection.

A bit of reflection will make clear why Malthus’s principle of population was considered “dismal,” a term first applied to Malthus’s work by the great British historian, Thomas Carlyle, in 1840.[12] Malthus’s principle implies that it is absolutely impossible to create a human society in which each individual member can expect to enjoy a comfortable and productive life. In fact, a nearly perfect human society, that is, one able to completely eliminate suffering whether through violence or disease and to treat all citizens humanely, can nonetheless never escape the suffering which results from overpopulation in relation to food supplies.

Nearly a century after Malthus’s work appeared, T. H. Huxley, known as “Darwin’s Bulldog,” made the point vividly. Huxley first imagined a utopian society as nearly perfect as human artifice can make it. As he formulated the matter in an 1893 lecture:

Thus the administrator might look to the establishment of an earthly paradise, a true garden of Eden, in which all things should work together . . . But the Eden would have its serpent . . . Man shares with the rest of the living world the mighty instinct of reproduction, the tendency to multiply with great rapidity. The better the measures of the administrator achieved their object, the more completely the destructive agencies of the state of nature were defeated, the less would multiplication be checked . . . ?

Thus, as soon as the colonists began to multiply, the administrator would have to face the tendency of the reintroduction of the cosmic struggle into his artificial fabric . . .[13]

Notice that Huxley fully understands the distressing consequence of Malthus’s “Principle of Population”: the more perfect the human society and the more comfortable its members, the quicker they will reproduce and the sooner will their carefully engineered social fabric unravel. Social harmony will inevitably be dissolved by a desperate struggle for existence brought about by a food supply that can never increase as quickly as population.

The Implications of Malthus’s Theory

Though Malthus’s Principle of Population brought the three men together, their thinking diverged when they considered its implications.

Malthus believed his theory demonstrates that efforts to aid the needy members of a society are both futile and counterproductive. An increase in food supplies will only prompt an increase in population, which will continue expanding until human reproductive appetites overwhelm food supplies and the population crashes. As a practical consequence, Malthus advocated abolishing the British poor laws, which were the public assistance programs of his day. Malthus formulated his ideas in this way:

I have reflected much on the subject of the poor-laws and hope therefore that I shall be excused in venturing to suggest a mode of their gradual abolition . . . To this end, I should propose a regulation to be made, declaring that no child born from any marriage, taking place after the expiration of a year from the date of the law, and no illegitimate child born two years from the same date, should ever be entitled to parish assistance . . . If any man chose to marry without a prospect of being able to support a family, he should have perfect liberty do so. Though to marry, in this case, is, in my opinion clearly an immoral act, yet it is not one which society can justly take on itself to prevent or punish; because the punishment provided for it by the laws of nature falls directly and most severely upon the individual who commits the act.[14]

Malthus was convinced that only the prospect of miserable death by starvation for themselves and their children can suffice to curb the human sexual appetite. Notice also that Malthus did not assert that human beings necessarily desire to reproduce. Instead, their passions are strictly sexual. Of course, for most of human history, there has been a tolerably close link between sexual activity and reproduction.

Darwin, on the other hand, drew a very different inference from the pressures of selection. He says,

The following proposition seems to me in a high degree probable—namely, that any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts, the parental and filial affections being here included, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well, or nearly as well developed as in man.[15]

As Darwin saw it, beings living in groups must develop certain personal qualities if they are to maintain the integrity of their society. Such qualities include sympathy for others, cooperativeness, and a sense of fairness. Without these traits, a group cannot cohere. On the assumption that certain species acquire evolutionary advantages from communal living, selective pressures would introduce the above qualities into the organisms. But, Darwin believed, if such beings also acquire sufficient intelligence, both moral principle and moral practice will eventually develop from these social instincts.

Wallace, though he greatly admired Darwin, was unwilling to follow him to this conclusion. He agreed with Darwin’s view that natural selection operating on social creatures would generate the personal qualities of sympathy, cooperation, and fairness needed to preserve social cohesion. Nonetheless, later in his life, and much to Darwin’s dismay, Wallace became a spiritualist.[16] One result is that he became convinced that natural processes cannot account for a spiritual matter such as morality. He said,

We thus find that the Darwinian theory, even when carried out to its extreme logical conclusion, not only does not oppose, but lends decided support to, a belief in the spiritual nature of man. It shows us how a man’s body may have been developed from that of a lower animal form under the law of natural selection; but it also teaches us that we possess intellectual and moral faculties which could not have been so developed, but must have another origin; and for this origin we can only find an adequate cause in the unseen universe of Spirit.[17]

So who is correct? As it happens, Darwin had a simple and elegant response to Wallace’s concerns: intelligent social beings with sophisticated powers of communication will have ample reason to be concerned about their reputations. This is because they will recognize that they are likely to need the assistance and cooperation of others. But they will also realize that support from their fellow group members is unlikely to be provided if they are not thought cooperative or helpful by the other group members. After a time, the pressures of natural selection are likely to transform this concern for reputation into the traits of character that constitute an individual others will wish to assist. In other words, the concern for reputation will be transformed into the prompting of morality.[18]

Darwin’s simple argument remains fruitful. It is presently the cornerstone of 21st-century research on the processes by which standards of moral conduct may have emerged. The recent works of Mark Hauser and Richard Joyce are notable examples of research for which Darwin’s insight remains relevant and fruitful.[19] In addition, many know of the work of Frans de Waal, the noted primatologist and psychologist at the Yerkes Primate Research Center in Atlanta. His studies of primate societies have yielded fascinating results concerning their expressions of sympathy, cooperation, and fairness.[20]

Wallace was well aware of Darwin’s argument and devised a forceful response. The nub of his position is that Darwin did not offer rigorous proof of his views.[21] Darwin himself understood that his train of thought was speculative. Of course, Darwin’s lack of conclusive proof is not evidence for Wallace’s spiritualism. Strictly speaking, the issue remains undecided. However, the contemporary researchers mentioned above have found Darwin’s ideas more useful in their investigations. So, in that sense, Darwin’s view has prevailed.

But what about Darwin and Malthus?

Malthus’s “Principle of Population” implies that in all times and under all circumstances population must necessarily increase far more quickly than food production. No matter how small the initial human population or how vast the untapped natural resources at their disposal, human groups will always find that their propensity to reproduce must surpass their ability to increase food production. If Malthus is correct, human beings are well advised to short-circuit whatever naturally evolved empathy they may have for others. In Malthus’s view, seeking to help needy people only makes the inevitable population crash more painful. That is, aiding the poor by giving them food will allow them to reproduce in larger numbers. So when this increase in population surpasses the land’s capacity to produce food, even more people will be alive to suffer the fate of starvation. In his view, the poor laws only made the difficulties of overpopulation more devastating.

Human population trends from Malthus’s day to the present time reveal a major difficulty with his argument. In Malthus’s day, around 1800, the world’s human population was approximately one billion. Though the world’s human population remained relatively constant from human prehistory to the period of the Industrial Revolution, it has increased markedly from 1800 to the 21st century. Presently, the world holds well over six billion human beings, and the United Nations expects the human population to increase to around nine billion by the middle of this century.[22] But there have as yet been no massive human die-offs, at least not as the result of population outstripping food supplies. There has been starvation aplenty, but it has resulted from war, civil turmoil, or natural disaster rather than population outstripping food supplies. In fact, one distinguished researcher, Amartya Sen, believes that the most common cause of starvation in the world is not lack of food. Rather, he believes the problem is that people do not have money to buy it. So he proposes giving needy people money rather than food.[23]

Two additional factors add insult to Malthus’s injury. First the number of the world’s people living in extreme poverty, understood as living on less than $1 per day, has plummeted in the past 25 years. In 1981, approximately 1.5 billion of the world’s people lived on $1 per day or less. By 2002, that number had been cut by 400 million. Most of the improvement has occurred in east and south Asia. A good bit of the improvement for people in those areas is the result of the spectacular economic progress of China and India in recent decades. Chen and Ravallion note that should this trend continue the number of people living on $1 or less per day will be cut in half yet again by 2015,[24] again a result of economic progress in east and south Asia. It is also noteworthy that in 1980 the world’s human population was approximately 4.5 billion, but it has since grown to well over 6 billion.[25] So even though the world’s human population increased by more than one-third during the last 30 years, the portion of the world living in extreme poverty decreased significantly. To be sure, a considerable number of people still live on between $1 and $2 a day.[26] Nonetheless, there is clear improvement despite the considerable increase in population.

The second difficulty for Malthus’s theory is that a considerable portion of the world’s human beings have been steadily escaping poverty and becoming members of the middle class. Conceptions of “middle class” differ. One researcher defines it as the circumstance in which individuals have at least one-third of their income remaining after paying for food and shelter. The extra one-third of income can then be employed for a variety of things. Many will dispose of it on consumer goods, such as refrigerators or air conditioners. However, many will also use it for health care or education, both of which can considerably increase their standard of living. Using this definition, researchers conclude that around half of the human beings in the world at the present time are members of the middle class.[27] Further, many are confident the human middle class will continue to increase as a portion of the human population.

Neo-Malthusianism

Despite these observations, Malthus’s theory retains considerable appeal and is prone to enjoy resurgence in periods of human turmoil.[28] In particular, it springs back to life in times of economic distress. Hence, neo-Malthusianism reappeared in the turbulent 1960s, then again in the 1970s.[29] In 2008, a newspaper headline—“Malthus Redux: Is Doomsday Upon Us, Again?”—demonstrated that neo-Malthusianism revived yet again during the global economic crisis of the first decade of the 21st century.[30]

Nonetheless, to salvage Malthus’s theory, the neo-Malthusians introduced an important modification. Rather than claiming that population growth must at all times and in all places outstrip increases in food supply, the neo-Malthusians borrowed an idea from ecology, that of carrying capacity. For the neo-Malthusians, there must be a limit to the amount of food the earth can produce and, therefore, a limit to the number of human beings it can support. The clear implication is, if human population increases beyond the limit of maximum food production, a population crash must follow.[31] This claim must be right. The earth is not becoming larger. So land and water on the earth are certainly limited resources. If so, the amount of food the earth can produce must have an upper boundary. This reformulation of Malthus’s position is clearly not weakened by the above data regarding population increase and declines in human poverty. Instead, to the extent that the earth’s human population continues to grow, the limit must be drawing closer. In addition, the degradation of the environment by polluting air and water decreases the land available for food production, and thus brings the upper limit of food production closer still.

But this neo-Malthusian position prompts two questions. The first, obvious, question is: When will the limit of maximum food production be reached? After all, the fabled religious mystics who predict the end of the universe will also be correct someday. As the “Again” in the newspaper headline, “Malthus Redux: Is Doomsday Upon Us, Again?,” indicates, Malthusian catastrophes have been declared a number of times in the past.[32] But in each case, humanity has been able to muddle through. Hence, the great difficulty is determining when the Malthusian catastrophe is likely to arrive. The second question is: should we live our lives now on the assumption that the boundary of maximum food production will be crossed soon?

Important though the above questions may be, there is clearly insufficient data to address the first question. Since the first remains beyond resolution, the second must remain in limbo as well. On the other hand, if we do not know when the limit of maximum food production will be crossed, and if the consequences of crossing it include enormous human suffering, we are prudent to begin the effort to limit human population growth at the present time. Of course, in addition to that prudent caution, there are additional benefits to the environment to be had by decreasing the strain on natural resources and reducing the burden of pollution additional humans will inevitably create.

Reining in Population Growth

However, if prudence dictates limiting population growth, the inevitable question is: What is the best way to halt the burgeoning increase in the number of human beings? There are several possibilities.

Malthus endorses the following approach. He says,

In most countries, among the lower classes of people, there appears to be something like a standard of wretchedness, a point below which they will not continue to marry and propagate their species. This standard is different in different countries, and is formed by various occurring circumstances . . . In an attempt to better the condition of the labouring classes of society our object should be to raise this standard as high as possible.[33]

There is presently some data to support Malthus’s approach. The Soviet Union collapsed in the early part of the 1990s and fractured into a number of separate states. Russia is the largest resulting nation. During this period, the Communist Party was ousted from power. In fact, Russia declared it illegal for a number of years. However, during its 70-odd years of rule, the Communist Party became so intricately intertwined with all facets of Soviet society that Russia’s major institutions collapsed along with the party. Both governmental and economic chaos ensued. Given the stress of the era, the economic uncertainty, and the general demoralization of the population, it is no surprise that the Russian birthrate plummeted.[34] And it is worth noting on behalf of Malthus’s notion of the subjectivity of misery, that, though they were indeed miserable, the inhabitants of the former Soviet Union enjoyed a far higher standard of living than people in many parts of the world.

Nonetheless, many have an understandable reluctance to make people miserable, particularly when many of the world’s human beings appear to have ample misery. Aside from that concern, however, the subjectivity of Malthus’s approach is troubling. As noted above, billions of people in the world are far poorer than were the Russians even at the worst of their economic and social chaos. Though they are quite likely distressed by their circumstances, ample data reveal that the poorest, most abject nations of the world also have the highest birthrates. Even if Russian society had not eventually recovered from the trauma of the early 1990s, it is entirely possible that Russians would eventually have become accustomed to their circumstances and returned to their usual childbearing practices.

As mentioned above, the nations of the world with the neediest populations commonly also have the highest birthrates. It is difficult to know what could be done to make people in those nations feel so miserable that their appetites for reproduction would shrivel. However, given their present state of deprivation, it is entirely possible such measures would necessarily be indefensibly cruel. So at the very least, it would be reasonable to determine whether any other options for population reduction remain.

However, modern technology has recast the Malthusian problem. The world now possesses effective and widely available methods of birth control. Malthus’s assumption that sexual activity would inevitably result in reproduction is outdated. He presumed that the only way to short-circuit reproduction was to make people so miserable that they would lose interest in sexual activity. At present, of course, human beings are able to engage in sexual activity without necessarily risking reproduction. The passion between the sexes may well remain as strong as in Malthus’s day, but there is no longer reason to believe sexual activity will inevitably result in more human beings. Even the demoralized Russians of the early 1990s employed birth control to prevent reproduction. That is, they chose not to have children.[35] If so, Malthus’s question can usefully be recast as the question: What circumstances will prompt human beings to decide against reproducing?

One obvious way to attempt to convince people to forgo reproduction is the age-old technique of coercion. Concerned by its burgeoning population, the government of mainland China employed this approach with its one-child-per-family policy introduced in 1979. As the name implies, the government stipulated that each married couple could have one child only. This policy relied on both incentives and punishments to gain compliance by the Chinese people. Its menu of punishments included fines and property or job loss. For the most part, China’s policy was enforced by local governments. Because there is no entrenched rule of law in China and government oversight was spotty, there was considerable variation in the execution of the one-child policy from district to district.

Nonetheless, the fertility rate in China prior to 1979 was 2.9 children per woman. Following the introduction of the one-child-per-family policy, the fertility rate sank to 1.7 children per woman, and remains at that level to this day. Though 1.7 is considerably more than 1 child per woman, it is entirely low enough to keep the Chinese population in check. Globally, the fertility rate needed to maintain a stable population is 2.1 children per woman. The 2 children replace the parents, while the .1 allows for the portion of children who do not survive long enough to produce children of their own. In fact, the Chinese government claims that its policy has resulted in 250 million to 300 million fewer births than would have occurred without its policy.[36]

The Chinese one-child policy has prompted a number of questions. First, some researchers wonder just how much of the reduction in fertility is due to the one-child policy and how much the result of other factors, such as urbanization or the emergence of a culture in which small families are desired.[37] Some authors note that the fertility rate in China had fallen considerably even before the one-child policy was put into effect. In addition, Deng Xiaoping, China’s leader from 1978 to 1992, introduced wholesale economic reform during the same period. Large numbers of Chinese flocked from the countryside to the cities. Urban dwellers have lower birth rates (in part because they have less space to house a family) than those in rural areas. In addition, many young Chinese women left their villages to seek jobs in factories. They wished to earn sufficient money to allow them to return to their villages and begin families. As a result, some will remain unmarried during their prime childbearing years and some may not return to their villages.

A more pressing difficulty is that it is unlikely that the Chinese policy can be successfully exported. The policy requires significant resources of social control and entails far greater governmental intrusion into personal lives than is likely to be tolerated in many other parts of the world. So while the one-child policy may or may not be effective in China, it is unlikely that it could be successfully applied in other nations of the world with very different cultures and very different systems of government.

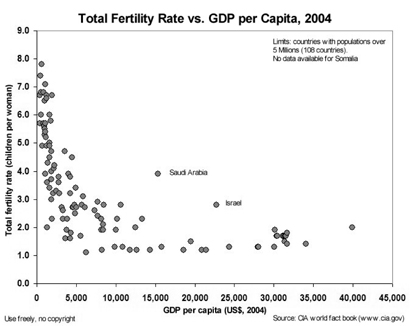

Another approach to reducing the human fertility rate is suggested by this chart:

The chart strikingly illustrates an intriguing correlation. Notice that the chart’s curve is concave. The fertility rate shoots well above 2.1 (the fertility rate necessary to maintain a stable population) when a nation’s gross domestic product (or the total value of all the goods and services produced within the nation) drops below $5,000 per person. As the GDP increases above $5,000, the fertility rate drops well below 2.1.

That phenomenon is known as the demographic-economic paradox and is well documented. The term refers to the fact that fertility generally falls below the replacement level of 2.1 as national wealth increases. It is termed a paradox because many (including Malthus) assumed in the past that the more wealth people possess, the more children they will have. Nevertheless, the demographic-economic paradox has the happy implication that a most effective way to motivate human beings to forgo reproduction is simply to make people minimally financially solvent. A per capita GDP of $5,000 is quite modest, only slightly more than a tenth of the $46,859 of wealth per person enjoyed by the citizens of the United States.

But pleasing though this approach may be, the community of nations has not yet proven adept at increasing the wealth of impoverished nations. It is entirely true that the economies of India and China have made enormous strides in the past several decades. China’s per capita GDP is now over $5,000, while India’s has risen to slightly more than half that amount at $2,700. Yet no one knows how to transfer success to impoverished nations elsewhere.

Furthermore, it would be both helpful and illuminating to discover why a GDP of $5,000 apparently motivates human beings to have fewer children. Presumably, people with incomes at or above that level do not hold the belief that having many children is desirable. But there is no obvious reason why simply having a certain level of wealth should bring about this change. It is possible that the money brings other changes and that these other consequences are responsible for a new attitude toward childbearing.

As it happens, the example of the Indian state of Kerala holds a hint of how to address these questions. The citizens of Kerala are not even modestly wealthy. They have a per capita income of at most $810 per year, far below the $5,000 per year that triggers the demographic shift. Nonetheless, Kerala’s citizens enjoy a life expectancy on par with that of the inhabitants of far wealthier nations. Other measures of the quality of life, such as average educational level and access to health care, are also extraordinarily high. And, perhaps not coincidentally, Kerala’s fertility rate is approximately 1.8 per woman.[38] If Kerala is a good example, significant reductions in fertility can be achieved through measures that improve access to education and health care. If so, the key to the reduction of fertility is not money per se but the improvements in human life, such as education and health care, that higher incomes often allow.

A clue to Kerala’s success is found in the United Nations Human Development Index. The first United Nations Human Development Report was issued in 1990. It contained a new measure of human development, the Human Development Index, which combined the elements of life expectancy, educational attainment, and income into a single, composite metric, the HDI. The HDI’s achievement was the creation of a single statistic that can serve as a frame of reference to judge both social and economic development in the world’s nations. The HDI sets a minimum and maximum for each dimension, called goalposts, and then shows where each country stands in relation to the goalposts, expressed as a value between 0 and 1.[39] At this point, there is likely little surprise that the nations ranking highest on the Human Development Index also have the lowest birthrates, while those ranking lowest on the HDI have the highest birthrates.[40] If so, it is entirely possible that Kerala’s strong performance on the other measures of human development outweigh its very modest economic production.

Nonetheless, Amartya Sen has focused the picture still more tightly:

There is considerable evidence that fertility rates tend to go down sharply with greater empowerment of women. This is not surprising, since the lives that are most battered by the frequent bearing and rearing of children are those of young women, and anything that enhances their decisional power and increases the attention that their interests receive tends, in general, to prevent over-frequent child bearing. For example, in a comparative study of the different districts within India, it has clearly emerged that women’s education and women’s employment are the two most important influences in reducing fertility rates. In that extensive study, female education and employment are the only variables that have a statistically significant impact in explaining variations in fertility rates across more than three hundred districts that make up India. In understanding inter-regional differences, for example, the fact that the state of Kerala in India has a fertility rate of only 1.7 (which can roughly be interpreted as 1.7 children on average per couple) in contrast with many areas which have four children per couple (or even more), the level of female education provides the most effective explanation.[41]

If Amartya Sen is correct, then the key factor in reducing human fertility is not increased wealth or even increasing human development as understood by the United Nations. Rather, the key is increasing educational and economic opportunities for women. So of the elements in the Human Development Index most pertinent to fertility reduction, providing education and economic opportunity to women appears to be the critically important factor. Apparently, as women become more educated and have more economic opportunity, they determine that their lives will be most satisfactory if they forgo having additional children. In happy consequence, a human community serious about reducing fertility rates may be able to do so without huge cost or complication simply by increasing the amount of schooling available to women and making it possible for them to participate in their economies.

Conclusion

Though sufficient misery may at times deter people from reproducing, the difficulty, as the subjectivity of Malthus’s standard implies, is that people may become accustomed to any particular level of wretchedness. Furthermore, as the charts which map fertility against poverty indicate, the most miserable sectors of the world, such as Afghanistan, also have the highest fertility. The Chinese one-child program is possibly effective, but it is unlikely that it can be successfully exported.

So it seems the sociable qualities that Darwin believed are required for living in groups hold the key to preserving human life after all. If the observations of this chapter are correct, the same sympathy, cooperation, and sense of fairness that enabled ancient human beings to survive as social beings under conditions of great need may also help humanity survive its present-day challenges of prosperity and rapid human population growth. Simply increasing educational levels and economic opportunities for all human beings and working to ensure that they have adequate health care are key factors for reducing fertility. But, more precisely, increasing the educational level for women and opening doors to increased economic activity may be the centrally important factors. Not only can these things be easily provided by the world community, they are available at a decidedly modest cost.

Notes

1 - Barrett, P. and R. Freeman. 1989. The Works of Charles Darwin, vol. 29. London: William Pickering.

2 - Lewontin, R. 2009. “Why Darwin?” The New York Review of Books 56 (9): 20.

3 - Slotten, R. 2004. The Heretic in Darwin’s Court: The Life of Alfred Russel Wallace. New York: Columbia University Press, 6.

4 - Wallace, A. 1905. My Life: A Record of Events and Opinions, vol. 1. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 362.

5 - Wallace, A. 1858. On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type. http://www.zoo.uib.no/classics/varieties.html.

6 - Slotten, 2004.

7 - Malthus, T. 1789. An Essay on the Principle of Population, 2nd ed. ed.P. Appleman. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2004.

8 - Ibid.

9 - Ibid.

10 - Ibid.

11 - Ibid.

12 - Carlyle, T. 1840. Chartism. London: James Fraser, 109.

13 - Huxley, T. and J. Huxley. 1947. Touchstone for Ethics. New York: Harper and Brothers, 50–1.

14 - Malthus, 1789.

15 - Darwin, C. 1871. The Descent of Man. Amherst: Prometheus Books, 1998, 101.

16 - Slottin, 2004.

17 - Wallace, A. 1889. Darwinism: An Exposition of the Theory of Natural Selection With Some of Its Applications. London: Macmillan and Company, 478.

18 - Darwin, 1871.

19 - Hauser, M. 2006. Moral Minds: How Nature Designed Our Universal Sense of Right and Wrong. New York: Ecco Press.

20 - de Waal, F. 1996. Good Natured: The Origins of Right and Wrong. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. This work is a useful introduction to De Waal’s research findings and thought.

21 - Wallace, 1889.

22 - United Nations Population Division. The World at Six Billion. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/sixbillion.html.

23 - Sen, A. 1998. The Possibility of Social Choice. Lecture given for the Nobel Prize, Stockholm. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/1998/sen-lecture.pdf.

24 - Chen, S. and M. Ravallion. 2004. “How Have the World’s Poorest Fared Since the Early 1980s? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3341.” The World Bank Research Observer 19 (2). http://wbro.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/19/2/141.

25 - United Nations Population Division, 1999.

26 - Chen and Ravallion, 2004.

27 - Parker, J. 2009. “Burgeoning Bourgeoisie.” Economist, February 12. http://www.economist.com/specialreports/displayStory.cfm?story_id+13063298.

28 - Malthus, 1789.

29 - Hardin, G. 1968. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science 162: 1243–48; Meadows, D., D. Meadows, et al. 1974. The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe Books.

30 - McNeil, D., 2008. “Malthus Redux: Is Doomsday Upon Us, Again?” New York Times, June 15. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/15/weekinreview/15mcneil.html.

31 - Hardin, 1968.

32 - McNeil, 2008.

33 - Malthus, 1789.

34 - Perelli-Harris, B. 2006. “The Influence of Informal Work and Subjective Well-Being on Childbearing in Post-Soviet Russia.” Population and Development Review 32 (4): 729–53.

35 - Ibid.

36 - Hesketh, T., L. Lu and Z. Wei Xing. 2005. “The Effect of China’s One-Child Family Policy After 25 Years.” The New England Journal of Medicine 353 (11): 1171–76.

37 - Ibid.

38 - Drèze, J. and A. Sen. 2002. India: Development and Participation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 97–101; 112–42.

39 - United Nations Development Program. Human Development Index. http://hdr.undp.org/en/humandev/hdi/.

40 - Leete, R. and M. Schoch. 2003. “Population and Poverty: Satisfying Unmet Need as the Route to Sustainable Development.” Population and Poverty 8: 9–37.

41 - Sen, A. 2003. “The Importance of Basic Education.” Guardian, October 28. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2003/oct/28/schools.uk4.

- Darwin, Malthus, and Wallace believed that the most important feature of human life is the scarcity of food. In the United States, we have an overabundance of food. Does this oversupply cause as many problems as scarcity?

- How did Malthus’ “Dismal Theorem” help Darwin and Wallace formulate their theory of natural selection?

- Why did Darwin believe that the pressures of natural selection would lead to the development of ethics by intelligent beings? And, do you think his inference is correct?

- Malthus believed that his “Dismal Theorem” implies that it is impossible to have a human society in which every member would have a good life. Thomas Huxley gives an example of an ideal society would necessarily face the problems Malthus foresaw. Can you imagine a society that would avoid these problems and provide a good life for all its members?

- Why would an increase in personal wealth tend to result in a reduced birth rate?

- Why would extreme poverty be closely associated with high birth rates?

- How is it possible that an extremely poor place like Kerala State in India is able to achieve low birth rates?