Between the Hitler-Stalin Pact in August 1939 and the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, even as the Communist wing of what was no longer a Popular Front urged an isolationist stance on stage and screen, the motion picture industry, so long quiescent to the rise of Nazism, sprang into decisive action. From 1939 to 1941, Hollywood signed up ahead of the formal call to arms with its own line of over-there propaganda designed to enlist the nation into the war raging in Europe.

The first entry, released in April 1939, was Warner Bros.’ Confessions of a Nazi Spy, the film Martin Dies was so disappointed in. Based on a sensationalistic espionage trial held in New York in 1938 and billed as “the film that has the guts to call a swastika a swastika!”, the farsighted docudrama warned of a division-sized fifth column of American Nazis, a renascent German war machine, and the inevitable confrontation between the forces of democracy and totalitarianism.

Though not the breakthrough hit Warner Bros. had hoped for, Confessions of a Nazi Spy opened the floodgates for anti-Nazi cinema. Beginning in September 1939, low-budget independent outfits and major studios alike geared up to indict Nazism and urge America to take defensive action. B-caliber quickies, women’s melodramas, tense thrillers, and dark satires—the anti-Nazi thread connected films as diverse as The Beast of Berlin (1939), Escape (1940), Foreign Correspondent (1940), The Mortal Storm (1940), Manhunt (1940), The Man I Married (1940), and The Great Dictator (1940). Patriotic renewal and national defense were the common themes of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), I Wanted Wings (1940), Flight Command (1940), The Fighting 69th (1940), and Sergeant York (1941).

Watching Hollywood’s aggressive foray into geopolitics, the Communists stood on—or heckled from—the sidelines. After August 23, 1939, the New Masses lambasted the anti-Nazi pro-defense cycle as errant warmongering. Warner Bros.’s egalitarian Great War combat film The Fighting 69th was “an unbelievable mess of bilge and militarism.” Twentieth Century-Fox’s conjugal melodrama The Man I Married—originally titled I Married a Nazi—taught that “America must get ready to go to war and go to war soon, which is what our homegrown fascists want us to believe.” The air power friendly I Wanted Wings was “propaganda of unbelievable vulgarity…all the words which describe it adequately are unprintable.”1 When the party apparatchiks sent out the word, the writers in the ranks took verbatim dictation.

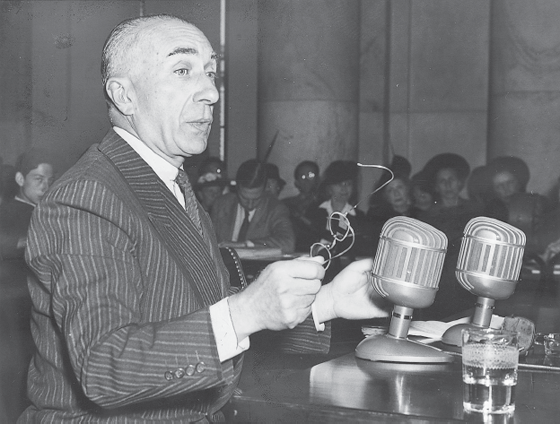

Nicholas M. Schenck: “Whatever anti-Nazi films we made don’t show one hundredth part of what we all know is going on in Germany.”

American Communists found common cause with an unlikely group of kindred spirits in the U.S. Senate. Isolationist Republicans had long been infuriated at FDR’s metastasizing federal agencies and his blatant orchestration of same for New Deal causes. Now, the Republicans believed, FDR’s foreign policy was leading the nation headlong into war—with his Hollywood minions aiding and abetting at every corner Bijou.

The fresh attack on Hollywood’s politics differed in a crucial way from the allegations of the Dies Committee. The reek of antisemitism swirled around the charges of war propaganda emanating from the U.S. Senate. No one denied that Hollywood’s Jews had a personal stake in defeating Nazism, but a few senators implied that ethno-religious solidarity outweighed their patriotic duty to America.2 On August 1, 1941, in a speech broadcast to a national audience over CBS, Sen. Gerald P. Nye (R-ND) addressed the America First Committee, an eight hundred thousand–strong band of ardent isolationists, to vent his suspicions about the Jewish moguls. Nye scanned Hollywood’s marquees and spotted “at least 20 pictures…designed to rouse us to a state of war hysteria.”3 He demanded a senatorial probe into the saber-rattling films distributed by a cabal of foreign-born merchants of death.

Nye got his wish. From September 9 to 26, 1941, a subcommittee of the Committee on Interstate Commerce chaired by Sen. D. Worth Clark held hearings into “Propaganda in Motion Pictures.” Variety—which, despite the lineage shared by most of its masthead and readership, almost never broached the Jewish angle—detected the impulse behind the investigation and smoked it out, attributing the hearings “to the hatred of big business and the strongly anti-Semitic feeling of many members of Congress from small, hinterland districts. [The] Clark committee is made up of a number of men from these territories and they consider Hollywood the combined epitome of both their pet hatreds.”4

To represent the industry as counsel, the MPPDA chose Wendell L. Willkie, the Republican candidate for president in 1940 and a statesman held in universal esteem. An astute reader of the national zeitgeist, Willkie sensed that Hollywood had the wind at its back. Though wary of involvement in Europe, the vast majority of Americans had no love for the Nazis and supported FDR’s push for military preparedness. They were also flocking to Hollywood’s patriotic fare, especially The Fighting 69th and Sergeant York.

Making no apologies for Hollywood’s anti-Nazi slate, Willkie labeled the hearings a waste of time. “We abhor everything which Hitler represents” and “are proud to admit that we have done everything possible to inform the public of the progress of the national defense program,” he declared in a twenty-five hundred–word letter to the Clark Committee. Willkie also upbraided Senators Nye and his nativist ally Burton K. Wheeler (D-MT) for their not-so-veiled antisemitic slurs. The fact that the studios employed men “in positions both prominent and inconspicuous, both Nordics and non-Nordics, Jews and Gentiles, Protestant and Catholics, native and foreign born” only proved that Hollywood, like America, was a land of equal opportunity.5

With Willkie protecting their flanks, the moguls walked into the hearing room spoiling for a fight. Unapologetic and unbowed, Nicholas M. Schenck, president of Loew’s, Inc., MGM’s parent company; Harry M. Warner, president of Warner Bros. Pictures; Barney Balaban, president of Paramount Pictures; and Darryl F. Zanuck, vice president of production at Twentieth Century-Fox, offered full-throated defenses of the industry and its programming. The moguls not only flaunted their anti-Nazism and pro-Americanism, they argued that the two were synonymous.

Schenck spent two days on the stand parrying hostile questions. A streetwise, up-from-the-ghetto hustler who turned a handful of carny concessions and rickety nickelodeons into an entertainment empire, the Russian-born mogul held his ground. Condemning “the bestiality which is Hitlerism,” he stood squarely behind the targeted slate of MGM films, The Mortal Storm, Escape, and Flight Command. At every turn, the cagey old businessman outfoxed his interrogators.

“You don’t want unity with Hitler, do you?” Schenck snapped at Senator Clark. “Whatever anti-Nazi films we made don’t show one hundredth part of what we all know is going on in Germany.”6

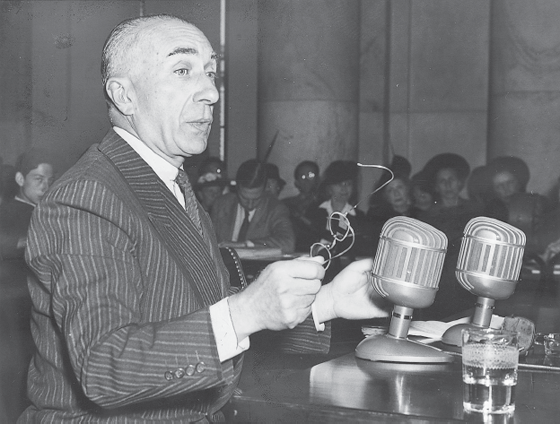

Harry M. Warner followed with a ninety-minute statement denouncing the Nazis, praising the American military, and lauding his studio’s role in alerting the American people to the dangers so alarmingly close to home. “In truth, the only sin of which Warner Bros. is guilty is that of accurately recording on the screen the world as it is or has been,” said Warner. He closed with a declaration that he had, in fact, made good on. “I am ready to give myself and all my personal resources to aid in the defeat of the Nazi menace.”7

Harry M. Warner, president of Warner Bros. Pictures, defends his studio before the U.S. Senate subcommittee investigating war propaganda in motion pictures, September 25, 1941.

Zanuck opened with a sardonic recitation of his Midwest Protestant credentials (“Senator Nye, I am sure, will find no cause for suspicion or alarm in that background”), and then lacerated the committee for trying to “subject the industry to an impossible censorship.” Like Warner, he did not deny but boasted of his patriotic record. “In this time of acute national peril, I feel that it is the duty of every American to give his complete cooperation and support to our President and our Congress, to do everything to defeat Hitler and to preserve America.” He reminded the senators that Hollywood didn’t create Hitler and the Nazis, “we have merely portrayed them as they are.”8

A packed, partisan gallery greeted the perorations to democracy with rapturous applause. On September 26, 1941, the hearings hastily adjourned, never to resume. The Hollywood moguls had routed the Washington senators on their home turf.

The Government Information Manual for the Motion Picture Industry: “Yes, we Americans reject communism. But we do not reject our Russian ally.”

With the outbreak of war on December 7, 1941, all was forgiven, or forgotten, “for the duration.” No longer facing off across tables in congressional hearing rooms, Washington and Hollywood locked arms and initiated the greatest collaboration between motion picture artistry and government policy in American history. Name-above-the-title directors enlisted in the armed forces to revolutionize the practice of documentary cinema. Disney animators decorated the fuselages of B-17s with buxom morale-boosters. Leading men went into uniform, some into combat, most into home front work that was not all that dissimilar from their civilian jobs. The screenwriters tended to be assigned to propaganda and educational work with the Office of War Information (OWI) or, along with the hands-on filmmakers, into the motion picture units of the various branches of the armed service. The writers who remained in civilian clothes continued their labors at the studios, often on war-minded feature films that embedded OWI values. The complete menu of programming—newsreels, cartoons, documentaries, and feature films—was marshalled to telegraph wartime messages of tolerance, teamwork, and sacrifice.

The transformation was not by happenstance. Under the OWI’s Bureau of Motion Pictures (BMP), the U.S. government issued detailed instructions on how best to adapt screen entertainment for wartime purposes. From June 1942 until June 1943, the agency was headed by Lowell Mellett, an intrusive bureaucrat who browbeat Hollywood into inserting ham-handed lectures into Hollywood feature films.

The advice from Washington was codified in a 167-page guidebook, The Government Information Manual for the Motion Picture Industry. The manual taught that an essential part of Hollywood’s wartime mission was to buck up America’s allies by celebrating the contribution of soldiers whose homelands were combat zones and signaling that Hollywood—and therefore America—knew that the great crusade against the Axis Powers was not a one-man show.

In valorizing “the might and heroism of our Allies,” no comrade in arms stood taller than the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which to avoid the troubling call-sign “socialist” was better referred to as Russia:

Yes, we Americans reject communism. But we do not reject our Russian ally. Where would we be today if the Russians had not withstood heroically the savage Nazi invasion of their land? Would we have the same confidence in eventual victory if we were not sure that the Russians would continue their stubborn struggle?9

Hollywood gave an emphatic answer to the questions. In obedience to the style book—and in accord with the temper of the times—three different studios produced three heartfelt A-picture salutes to the Russian war effort: Mission to Moscow (Warners, 1943), The North Star (RKO, 1943), and Song of Russia (MGM, 1944). All were ardently pro-Soviet, all were shamelessly dishonest in their depiction of the Communist system, and all seemed like a good idea at the time.

The North Star was first out of the gate: a big-budget extravaganza with an impeccable pedigree—produced by Samuel Goldwyn; directed by Lewis Milestone from a screenplay by Lillian Hellman; and set to a score by Aaron Copland, the composer laureate of musical Americana, and lyrics by Ira Gershwin, trying his hand at New Pioneer rhymes (“We’re the younger generation/And the future of the nation!”). Goldwyn poured enormous resources into his most expensive project to date, a pageant featuring over a thousand performers, with more than one hundred speaking parts.10

At first sight, The North Star looks like a pastoral musical. Russia is a peaceful and industrious land where villagers work each according his ability, each according to his needs. They labor, they sing, they dance, they recite party slogans (“Everybody must work!”).

The serenity of the steppes is shattered when waves of Luftwaffe strafe women and children and the Wehrmacht mops up with close-quarter slaughter. The vampirish perfidy of the invaders is quite literal: a medical unit drains the blood from Russian children for transfusions to wounded Nazis. Taking to the woods, the gallant Russians launch a guerilla insurgency, liberate their village, and summarily execute the Nazi doctors. “Killing Nazis was now a matter of national policy,” a gratified Lillian Hellman reminded the faint of heart.11

Though traversing the same territory and timeline as The North Star, Song of Russia is more romantically buoyant. “A Yank in Moscow,” blurbed the taglines, concealing the war-torn land angle. “Dashing Robert Taylor woos Susan Peters and it’s a wow!” Helming the project was Russian-born director Gregory Ratoff, a former character actor who spoke English with a thick-as-Borscht accent. An alumnus of the Moscow Art Theater, Ratoff had fled to America in 1922 after witnessing the bloodshed of the Bolshevik Revolution, an expertise in Soviet history that in no way informed his film.

As promised, dashing Robert Taylor plays Robert Meredith, a famous symphony conductor on a tour of Russia, who falls hard for Nadja (Susan Peters), a beautiful concert pianist, tractor driver, machine gunner, and cook from the collective farm village of Tschaikowskoya, a wheat-rich eden populated by harmonic singers and acrobatic line dancers. Soon the lovestruck Meredith and the multitasking Nadja are bridging the barriers of language and culture with a whirlwind courtship conducted in swank Russian nightclubs followed by a marriage in a traditional Russian Orthodox church. A blowout wedding party is choreographed with the verve of a Freed unit musical.

When the Nazis blast apart the festive bacchanal, Nadja organizes guerilla resistance and Meredith braves the dangers of a land on fire to reunite with his beloved. Nadja wants to stay and fight with her people, but she is persuaded by her fellow partisans that the best way she can contribute to the war effort is to go with her husband to America, don evening wear, and perform concerts for Russian War Relief.

Top: A troupe of folk dancers performs in MGM’s Song of Russia (1944). Bottom: Walter Huston, as ambassador Joseph E. Davies, Manart Kippen as Joseph Stalin, and Gene Lockhart as Soviet Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov in Warner Bros.’s Mission to Moscow (1943), the most duplicitous of Hollywood’s pro-Soviet troika.

If the portrait of a munificent and pacific Soviet Union in The North Star and Song of Russia was merely fanciful, of a piece with Hollywood’s soundstage versions of Paris, Vienna, and Budapest, the picture of the USSR in Mission to Moscow was a willful act of historical revisionism. Based on the purblind memoir by Joseph E. Davies, who served as U.S. Ambassador to the USSR from 1937–1938, at the height of the Stalinist purges and show trials; directed by Warner Bros.’s jack-of-all-genres Michael Curtiz; and written by Howard Koch, future member of the Unfriendly Nineteen, the film has a mission of its own: to whitewash the Soviet past and erase Stalin’s crimes in the interest of Allied unity.

Airbrushing the pages of history, the counterfactual hallucination opens with a rare double-barreled prologue: first, from the real-life Joseph E. Davies, an avuncular presence who wants to dispel American xenophobia and tell “the truth about the Soviet Union,” a nation “sincerely devoted to world peace”; and second, from the actor Walter Huston, as Davies, who praises Russia’s “gallant struggle to preserve the peace until ruthless aggression made war inevitable.”

Davies is a down-to-earth lawyer who reluctantly accepts his diplomatic mission from FDR as a patriotic duty. The ambassador initially shares his countryman’s wrongheaded notions about the USSR, but his eyes are opened by the rock-solid integrity and core decency of the Russian people, especially their warmhearted and idealistic leaders, Premier Vyacheslav Molotov, Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov, and, above all, the wise and kindly Joseph Stalin. All are played by huggable character actors: Oskar Homolka, Gene Lockhart, and Manart Kippen, respectively.

Newsreel footage of Soviet tanks, planes, and synchronized humans parading through Red Square on May Day (May 1, 1938) precedes the Nazi invasion of Austria (March 12, 1938), but chronology is the least of the departures from reality. The Moscow Show Trials have actually left the Soviet government “strengthened by the purge of its traitors,” while the Hitler-Stalin Pact was forced upon Stalin because of the anti-Soviet policies of the West.

After witnessing the nobility of the real Russia, Davies returns home to defend the socialist experiment against the calumnies of stateside Nazi sympathizers. In a pro-Soviet rally in Madison Square Garden, he explains the logic behind the Moscow trials, the Hitler-Stalin Pact, and the invasion of Finland, debunking the false narratives that have been foisted upon the American people.

Warner Bros. gave Mission to Moscow a roll out befitting a prestige production doing double duty as tribute to FDR and a gift to the USSR. On April 28, 1943, the studio took over the Earle Theater in Washington, D.C. for a preview hosted by the National Press Club. A contingent of four thousand media representatives attended. Speaking at a luncheon held before the preview, Ambassador Davies predicted: “Ten, twenty, and thirty years from now, the negative of Mission to Moscow will be taken out of the vault for reference in light of historical developments.”12 He had that right.

John E. Rankin: “Hollywood is the greatest hotbed of subversive activities in the United States.”

While World War II raged, HUAC hibernated. In a global conflagration, the interest in fifth columnists was subordinated to combating the clear and present danger from the other four columns.

The founder and guiding light of the committee sensed his glory days were over. In 1944, an ailing Martin Dies—“sick, disgusted, and exhausted”—announced his retirement from Congress. “I felt that the country had been given all the facts it needed to defeat Communism, and I asked myself, ‘What more can I accomplish under a hostile administration?’ ”13

With Dies putting himself on the sidelines, the committee that bore his name faced an uncertain future. Always controversial, HUAC was despised by FDR liberals who felt that the investigatory agenda sought more to discredit the Roosevelt administration than expose Nazi or Communist subversion. With each new session of Congress, liberal Democrats tried to block funding for a renewal of authorization.

Yet the efforts to abolish HUAC never quite succeeded: few congressmen wanted to be accused of being un-American by defunding the Un-American committee. In fact, what had once been a mere special committee of the House got not just a reprieve but a promotion.

HUAC’s savior was John E. Rankin (D-MS), a slick parliamentary infighter who finessed his colleagues into voting to make HUAC a permanent standing committee of the House.14 The war had schooled a generation of Americans in the lethal threat posed by subversive cells ready to spring into action at a signal from the Fatherland. Best to have antennae out and oversight ready.

Born in 1882 in the Jim Crow hamlet of Bolanda, Mississippi, Rankin was a lean, hungry-looking, rattlesnake-eyed, un-Reconstructed son of the Confederacy, virulently racist, nakedly antisemitic, and vulgarly nativist. First elected to Congress in 1920, he reaped the rewards of the seniority system and refined his skills as a back-channel fixer, assuring the continued subjugation of a tenth of the nation by blocking Democratic proposals to eliminate poll taxes and enact federal anti-lynching laws. In February 1944, after Walter Winchell denounced Rankin for ridiculing foreign-sounding names, the congressman took to the floor of the House to rail against “that little Communistic kike.” In 1946, again on the floor or the House, Rankin took after Winchell as a “slime mongering kike.”15 No more hissible incarnation of rank bigotry walked the national stage, at least not one sent to Washington by the voters. On that score, Rankin’s only real competition was his fellow Mississippian, Sen. Theodore Bilbo (D-MS).

Though a hater, Rankin was a cunning pol and HUAC was dear to his heart.16 On January 3, 1945, in the opening minutes of the inaugural House session of the Seventy-Ninth Congress, before the progressives could rally their forces, he galvanized a coalition of Southern Democrats and Republicans into rescuing HUAC from liquidation.17 Having secured HUAC a permanent slot in the congressional budget line, Rankin then stepped aside to let Rep. Edward J. Hart (D-NJ) chair the committee. Hart, however, had no appetite for the pursuit of un-Americans and soon resigned, leaving the interim chairmanship to Rankin.

Temporarily at the helm, Rankin set his sights on the most prominent outpost of Jewish influence in American life. On June 30, 1945, he announced an investigation into “the greatest hotbed of subversive activities in the United States,” the command center for “one of the most dangerous plots ever instigated for the overthrow of this Government.”18 He vowed that “Hollywood individuals and organizations are to be investigated” and that “some big name Hollywood stars and executives will enter into it before we are through.” Rankin stirred a combustible brew: Communism, Hollywood, and Jews.

Rankin dispatched three investigators to Los Angeles to expose the machinations of Hollywood Jewry, but solid opposition from the California delegation in Congress prevented him from staging a series of public hearings. With an eye to the midterm elections of November 1946, the Truman administration and Helen Gahagan Douglas (D-CA), head of the California delegation and wife of actor Melvyn Douglas, intervened to block the Rankin hearings. A furious Rankin vowed that no man—“or woman”—would stop his exposure of the “gigantic plot to overthrow the government” being hatched in Hollywood’s cafeterias.19 Still, for the moment, he was stymied.

Rankin could have pursued his vendetta by assuming the chairmanship of HUAC, but he was unwilling to relinquish his position as chairman of the powerful Committee on World War Veterans Legislation. The decision was a lucky break for HUAC. Understanding how repellent Rankin would be as the public face of the controversial committee, the Democratic leadership preferred a saner temperament for the permanent chairmanship and replaced him with the milder-mannered Rep. John S. Wood (D-GA). Wood pledged to proceed carefully and avoid “any witch hunt.”20

Yet Wood lacked the dogged determination to run down either witches or screenwriters; the hearings he presided over were lackluster, short on revelations, and shorter on headlines. HUAC languished until a new chairman took the gavel, a man whose blood was up for the hunt.

Eric A. Johnston: “I learned from personal experience that in many countries, the only America the people know is the America of the motion pictures.”

By V-J Day, Hollywood’s war work had not only contributed to the defeat of the Axis powers, it had pulverized the myth of pure entertainment. The last four years had proven Hollywood mattered—artistically, politically, culturally—and no one pretended otherwise, not even Hollywood.

A changing of the guard underscored the change in the role of movies in American culture. Since 1922, the official face of the motion picture industry had belonged to Will H. Hays, first president of the MPDDA, the cartel set up by the moguls in the wake of a wave of scandalous headlines (drug overdoses, rape allegations, and murder) that threated to derail the forward motion of a booming business. In the 1920s, moral degeneracy not Communist subversion was the menace thought to be emanating from Hollywood.

At ease on both Wall Street and Capitol Hill, Hays placed the industry on solid financial footing and secure political ground, cementing its ties to the high finance of the New York banks while keeping Washington regulators out of the picture. However, Hays’s most ingenious contribution to the stability of Hollywood cinema was in the realm of moral policing. In 1934, he established the Production Code Administration (PCA), a branch of the MPPDA tasked with censoring (or “self-regulating”) films during the process of production. To enforce the Production Code, the document that laid down the moral law, Hays appointed Joseph I. Breen, a no-nonsense, Jesuit-educated Irish Catholic. Breen took his assignment to clean up the movies as a solemn vocation. For the next twenty years, no Hollywood film was released without a thorough vetting from the Breen office.

Hays’s service had been amply rewarded—he was the highest paid lobbyist in Washington, D.C.—but by 1945 he was a relic from the age of flivvers and flappers. With peace at hand, the industry anticipated a new world order with daunting economic challenges. It also confronted an audience, both at home and abroad, whose attitudes had been transformed by the war, who already seemed impatient with the old pieties and end-reel uplift.

Two very dark clouds also blackened the horizon. First, television, the medium dreaded since the 1930s, was ready to begin its broadcasting day. Hollywood’s monopoly on screen entertainment was coming to an end.

Second, a final judgment was imminent in a government attack on Hollywood that was to prove far more lethal to the studio system than any body blow delivered by HUAC: the breakup of the vertically integrated monopoly forged by the major studios. Since the 1920s, the Big Five (MGM, Paramount, RKO, Warner Bros., and, after 1935, Twentieth Century-Fox) and the Little Three (Columbia, Universal, and United Artists) had held a vise-like grip on the means of motion picture production, distribution, and exhibition—a racket that assured a smooth pipeline of profit for the major studios while locking out independent producers from the cash flow.

The system was too crooked to remain forever unexamined by antitrust lawyers in FDR’s Department of Justice. Beginning in July 1938, the federal government initiated a series of legal actions under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to curtail the monopolistic practices. A decade-long pitched battle commenced, with the prosecutors attacking in fits and starts and the defendants maneuvering to delay the inevitable. Though Hollywood’s legal experts fought tenaciously, they knew that so egregious a combination in restraint of trade would not long survive an impartial judicial review.

To navigate the treacherous postwar waters, the industry needed a new helmsman, skilled in public relations, modern business practices, and international trade.

The search for a successor to Hays settled on Eric Allen Johnston, president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, member of the War Mobilization and Reconversion Board, and failed contender for vice president on the 1944 Republican ticket. He was also, which didn’t hurt, an Episcopalian with American roots stretching back to the Revolutionary War.

Born in 1895, reared in Spokane, WA, Johnston lived a classic Horatio Alger rags-to-respectability tale, right down to the early hardscrabble days as a newsboy hawking papers on the street. The literary motif continued into his higher education: while studying law at the University of Washington, he worked on weekends as a longshoreman on the Seattle docks. In 1917, upon American entry into the Great War, Johnston enlisted in the U.S. Marines. He missed combat on the killing fields of Europe, but served and traveled throughout China, Siberia, and Japan.

In 1922, mustered out and back stateside, Johnston sold and repaired vacuum cleaners, which led him into the electronics business, a high-return profit center in the Roaring Twenties. The role of a glad-handing front man suited him. When the stock market crashed in 1929, he not only survived but thrived in the bleakest of economic climates. By 1931, he was president of the Spokane Chamber of Commerce. An articulate and congenial public speaker, he presented a friendly face for the businessman in a decade with good reason to despise the type.

Beginning in 1942, upon his election as president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Johnston traveled around the globe on behalf of American business—including a trip to Russia to praise our Soviet ally and inspect the industrial might developed under the latest five-year plan.21 On the evening of June 26, 1944, accompanied by U.S. Ambassador Averell Harriman, he spent two and a half hours chatting with a jovial Joseph Stalin, who was decked out for the occasion in full military regalia. During the face-to-face, the official representative of American capitalism and the godhead of international Communism lauded each other’s economic systems. So congenial was the mutual admiration that Stalin jokingly told Johnston, “I’m the capitalist; you’re the Communist!”22

Johnston expanded on his meditations on a soon-to-be bipolar world in America Unlimited, published in 1944, a perfect title for an optimist who looked forward to the best years of the American century. Though the book did not mention the American motion picture industry once, the moguls knew star power when they saw it. Johnston was offered a sweet deal: a five-year contract at $150,000 a year plus $50,000 per annum in expenses.23 A quick study, he readily adapted his Kiwanis-speak to the new assignment. “No means of communication carries as much influence as motion pictures,” Johnston declared. “The industry is just now coming of age. It can exercise an even greater force and power in the postwar world.”24 The very model of the cordial, eloquent, enlightened American businessman, Hollywood’s new representative seemed minted for the role.

On September 19, 1945, at 1:00 P.M., at a meeting of the MPPDA in New York, the baton was formally passed from Hays to Johnston. “I learned from personal experience that in many countries, the only America the people know is the America of the motion pictures,” he said in a formal statement screened in the newsreels. “We intend always to keep that in mind.”25 Concurrent with Johnston’s appointment, the MPPDA changed its official designation to the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). The original name only gave more ammunition to the Department of Justice,

In New York, outgoing MPPDA president Will H. Hays (right) poses with incoming MPAA president Eric A. Johnston (left), September 19, 1945.

In confronting the challenges of the postwar world, the prospect of a congressional inquiry into Hollywood’s earnestly patriotic films and profit-minded personnel might have seemed far down on the list of Hollywood’s headaches. Who could seriously believe that a citadel of unbridled capitalism projecting a Roman Catholic catechism was, at heart, an outpost for Communist agents bent on destroying the system that had made its citizens rich?