As star witnesses, Mrs. Lela Rogers, Oliver Carlson, and Walt Disney were no match for the headline-grabbing matinee idols of the day before. No smitten matrons or swooning bobbysoxers crowded the corridors of the Old House Office Building hoping for a glimpse or an autograph. On the last day of the first week of the hearings, a morning-after calm settled over the room, all eyes on the weekend. Thomas had contemplated a special Saturday session, but opted against it “because some people have to attend football games.”1 Mindful of the priorities, he called only three witnesses and ended the day early.

The diminution in star magnitude was reflected in the erosion of the gallery. The press seats were half filled, the spectators half interested. Thomas had to gavel repeatedly for order, not to quiet fan hubbub or partisan outbursts but because of the restless chattering of bored reporters. “The final day of the week was so dull, it should have been left on the cutting room floor,” kvetched Florence S. Lowe, wringing more juice from the showbiz metaphor. A committee clerk scanned the empty seats and cracked, “Now we almost got room enough for the lawyers.” Behind the dais a newsreel soundman was snoozing contentedly.2

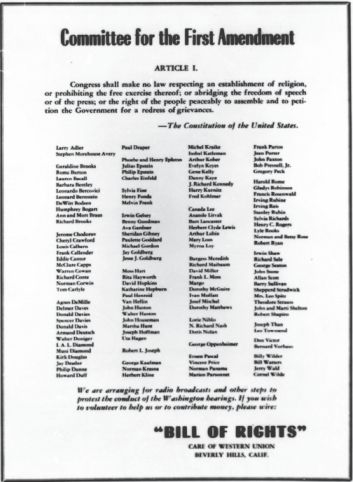

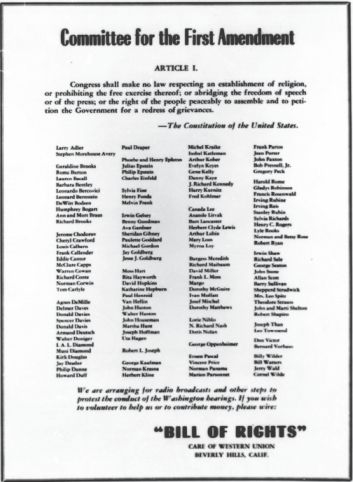

In Hollywood, the city awoke to more stirring news. The Committee for the First Amendment formally announced itself in a tandem series of full-page ads published in Daily Variety and the Hollywood Reporter. The ads were part of a venerable industry tradition: any Hollywood group with an agenda took to the pages of the trade press to post gripes, settle scores, and speak its piece. Along with the splashy advertisements for a studio’s slate of current releases, the advertisements gave a fair reading of the political temperature of the community in any given season.

The ad simply reprinted the text of the First Amendment, under which were the names of 139 Hollywood personalities—and a plea for support and funding.3

The Committee for the First Amendment formally announces itself in Daily Variety and the Hollywood Reporter, October 24, 1947.

In Hollywood, the response to the ad was electric. “We’ve had many calls from people complaining that their names should have been added to ours,” an excited Jane Strudwick, wife of actor Shepperd Strudwick, told the Daily Worker.4 The need for a support group to coalesce around was palpable. “It was a disturbing and frightening period in Hollywood,” recalled Lauren Bacall. “Everyone was suspect—at least, everyone to the left of center.”5

Lela Rogers: “I would suggest that the Congress of the United States immediately enact such legislation as will preserve the Bill of Rights for the people for whom it was designed.”

The first witness was a celebrity by parentage, Mrs. Lela E. Rogers, a staunch Republican in a Democrat stronghold, a founding member of the MPA-PAI, and the mother of screen star Ginger Rogers. Rogers mater seemed to be, and was often portrayed as, the Central Casting incarnation of an overbearing stage mother, a harpy channeling her energies into the career of her multi-talented daughter, who, unlike her mother, steered clear of roughneck political combat.

But though infinitely caricature-able, Rogers was no clinging appendage; she was a force of nature in her own right. Born in 1891 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, she married at nineteen, gave birth to her famous daughter, jettisoned a beta-male husband whose ambition did not match hers, and lit out to become a newspaper reporter. By 1916, Rogers was in Hollywood working as a screenwriter. When America entered the Great War, she was one of the first ten American women to enlist in the U.S. Marines. In uniform, she served as a press officer, edited training films, and rose in the ranks to become editor in chief of Leatherneck, the official monthly of her beloved Corps.

Retiring as a sergeant, Rogers returned to the motion picture business—for herself and the bundle of talent under her wing. In Hollywood, while her daughter danced from the chorus line into the spotlight, she established a theatrical school, worked as in-house dramatic coach at RKO, and freelanced as a theater producer, director, playwright, and manager. She also made a brief, in-joke appearance as Ginger’s mother in Billy Wilder’s screwball comedy The Major and the Minor (1942). Close, mutually nurturing companions, mother and daughter were also bound by religion. In a town thick with Jews and strewn with Catholics, Lela and Ginger stood out as observant Christian Scientists.

In the presidential campaign of 1944, Rogers backed FDR’s opponent and served as vice chairman of the Hollywood for Dewey Committee. Like many self-made success stories, she had scant sympathy for the little guy who hadn’t pulled himself up bootstrap-wise and deeply resented a federal government siphoning off her hard-earned income to support layabouts on the dole.

Rogers was widely quoted—and in leftist circles widely ridiculed—for her contention that a line from Tender Comrade (1943), the Edward Dmytryk-directed, Dalton Trumbo-scripted home front melodrama with a communitarian subtext and red-flag title, was evidence of the insidious “boring from within” practiced by Communist screenwriters. Emerging from her testimony during the HUAC hearings in May, she told newsmen that Ginger had balked at the subversive sentiment in the line “Share and share alike—that’s democracy!” Said Rogers: “Ginger refused to speak the line and it was put into the mouth of Kim Hunter, and it appeared in the picture!”6

Little wonder that H. A. Smith was dubious about Rogers’s usefulness as a witness. She “has considerable contempt for the Committee based again on the alleged unfavorable manner in which she feels Taylor was treated,” he noted, speaking delicately about Thomas’s double-cross of the actor. Smith worked to reassure her on that score. “If we can confine her testimony to brief, concise opinions, she will be of value. However, if she goes off and testifies to ‘share and share alike,’ it will do us more harm than good.” Rogers was scheduled to make her litigious appearance on ABC radio’s America’s Town Meeting of the Air the very night Smith wrote his report. “If she is able to hold up, then she should make a good witness,” figured Smith. “If not, it would be best not to call her.”7 Apparently, she passed the audition.

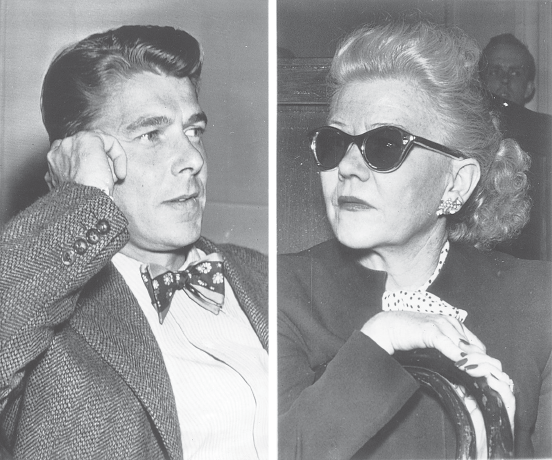

A graying blond in black-rimmed glasses, Rogers owned the room. It was evident where Ginger had gotten her looks. Ungraciously forgetting her sole female predecessor, the New York Herald-Tribune identified Rogers as “the first woman so far called before the committee” and noted that HUAC “had purportedly been calling only male Hollywood celebrities so it cannot be charged with conducting a beauty show.”8 She brought a spark of feminine flash and the whiff of perfume to the witness table, which could not be said of Ayn Rand.

Ronald Reagan and Lela Rogers listen to testimony, October 22, 1947.

Thomas was not so ungentlemanly as to deny a lady permission to read an opening statement. “Some of our executives have been deceived by the party liners they hired,” Rogers declared. “As a free people, we have no experience with such intrigue and conspiracy. Our executives were no more asleep [to Communism] than were our people or our government or the whole world in fact. The Communist is a trained propagandist, a highly disciplined operator, as is revealed by the testimony of former Soviet officials and ex-members of the Communist party. His ways are devious and not easy to follow.” Fortunately, Hollywood had been slapped to its senses by HUAC. “I think that once our executives see this, and know it for itself, they will be most happy to clean it out of their pictures. In the first place there have been very few pictures ever made with Communist propaganda in them that were successes at the box office.”

Having been prepped by the committee, Rogers rustled through her crib sheets as she spoke. “Well, uh, I would suggest that the Congress of the United States immediately enact such legislation as will preserve the Bill of Rights for the people for whom it was designed,” she said. “That precious bill was never intended to protect enemy agents, saboteurs, and spies, whether they’re American or alien born.”

Stripling asked whether Rogers would favor the outlawing of the Communist party.

“I favor the outlawing of the Communist party as an agency of a foreign government.”

“You consider them to be the agents of a foreign government?”

“I do, sir. Yes, sir.”

Unexpectedly, Representative McDowell interrupted to make a point about something that had been bothering him. The only Communist propaganda alleged to have seeped into the films themselves was the occasional instances of a banker depicted as a “no-good.” As evidence of Communist hegemony in Hollywood, wasn’t that pretty thin gruel? “Well, of course, I know many fine bankers, many patriotic men,” McDowell hastened to add. “I also know stinkers that should have been in jail 30 years ago. That doesn’t necessarily constitute Communist propaganda.”

“I can’t quote you the scenes exactly, but I can give you the sense of them,” Rogers said defensively. “When a Communist secures a firm footing in a picture, he surrounds himself only with other Communists.” As proof, she added a new film to the pro-Soviet slate: None But the Lonely Heart (1944), a Marxist critique of capitalism. The film was “moody and gloomy, in the Russian manner,” she said, quoting from a review. “I think this is a splendid example of what type of propaganda Communists like to inject into the motion pictures.” The film’s anti-capitalist centerpiece showed a son telling his mother, the owner of a second-hand store, “You’re not going to work here and squeeze pennies out of little people who are poorer than I am!” The line was unnecessary, she explained, “because in life there are always people richer or poorer than ourselves.”

Rogers had opposed the purchase of the property by RKO and the selection of playwright Clifford Odets to write and direct it. The reason was simple: Odets was a Communist. “For years I had heard that Mr. Odets was a Communist,” Rogers said, and he had never denied it. Confirming her birds-of-a-feather theory of infiltration, Odets had hired Hanns Eisler to compose the soundtrack.

Rogers admitted that the percentage of Communists in Hollywood was very small—perhaps smaller than 1 percent—but no matter. “The Communists don’t want numerical superiority, they want small, disciplined cells.” So insidious was their boring from within that Ginger herself may have unwittingly served the red cause by starring in Tender Comrade. Doubtless to Smith’s relief, she did not repeat her indictment of the “share and share alike” motto.

Rogers’s testimony—perhaps her very presence and personality—put Thomas in a good mood. “Thank you, and just go back to Hollywood and make a little more money so you can pay off that libel suit,” he joked, referring to the lawsuit pending against Rogers filed by SWG president Emmet Lavery, who was suing her for calling him a Communist on America’s Town Meeting of the Air.

Oliver Carlson: “The Communist attitude is, ‘Why worry about Moscow gold, when you can get Hollywood greenbacks?’ ”

The forty-eight-year-old, Swedish-born, Michigan-reared Oliver Carlson, a college teacher and self-styled expert on Communism, was best known, to the extent he was known at all, for working the Communism-in-Hollywood beat for the anti-Stalinist labor magazine the New Leader. Though Carlson had testified before the Tenney Committee in Los Angeles in 1941, and lectured as an authority on Communism, he was a bit player plucked from the crowd of extras for a brief close-up. He had recently authored a pamphlet for the Catholic Information Society entitled Red Star Over Hollywood warning that “few cities and few areas of American life have been so thoroughly ‘captured’ by Stalin’s agents as Hollywood and the movie industry.”9

Another former Communist in full repentance mode, Carlson said he had joined the party “when I was a kid,” but broke with it soon after. He maintained contacts in the party apparatus, however, and told a harrowing tale of fifth column subversion, not just in the Hollywood studios but in the Los Angeles school system (the American Federation of Teachers was “dominated by Communists”). The man behind the educational outreach was Eli Jacobson, an emissary from the New York branch of the CPUSA, who had been sent out to Hollywood in 1938 to set up the People’s Education Center, a school for subversion that had been “extremely effective for training in Communist ideology.” Jacobson had confided to Carlson that he was “sent to Hollywood by the party to conduct classes and educational propaganda among the film folk, not the rank and file but the elite.” Jacobson’s job “was to see to it that many important persons were softened up so as to agree to join front organizations the Communist party was forming in Hollywood.”

Carlson plied the conventional wisdom: that Communists targeted Hollywood because it was a propaganda powerhouse with a reservoir of gullible stars willing to fill party coffers. “I don’t have to tell this committee,” he told the committee, “that the motion picture industry is not exactly a sweat shop industry. Here is a treasure chest which is important. The Communist attitude is, ‘Why worry about Moscow gold, when you can get Hollywood greenbacks?’ ” Carlson re-imprinted the popular image of easily duped—and sometimes consciously sinister—Hollywood stars opening their checkbooks to bankroll international revolution.

Carlson scoffed at the notion that HUAC was an agent of “thought control,” as critics claimed. “The thought control is all on the other side. There’s something sadly amusing about people who endorse the Soviet government’s control of press and radio talking about thought control in this country.”

Representative Vail asked Carlson—“as a propaganda expert”—what he thought of the charges by MPAA president Eric Johnston and newspaper columnists that the HUAC investigation was but a veiled attempt to assert government control over Hollywood.

Carlson began a lengthy, convoluted answer, but Thomas cut him off. “I think we have gone too far afield,” decreed the chairman, as bored as everyone else.10

Carlson praised the committee and likened Communism to a cancerous growth that had to be cut out to save the organism “even though I know some good innocent people would be destroyed.” The former Communist had taken to heart the Leninist maxim about how an omelet couldn’t be made without breaking a few eggs.

Walt Disney: “We must keep the American labor unions clean.”

Walt Disney was not yet a signature—if not the signature—brand name of the American century, a man of lands, kingdoms, and synergistic empires, not yet the crinkly avuncular figure with an animated fairy flitting about his shoulders. Only after 1955 would the double-barreled marketing juggernauts of Disneyland and the ABC television show The Wonderful World of Disney make his visionary dreamscape and soothing persona as famous as the creatures that sprang from his drawing board. He was simply the father of the animated feature film, the premiere independent producer in Hollywood, and a certified genius.

Disney was also the creator and voice of Mickey Mouse, of course, and the sorcerer behind scores of cartoons and singalongs, most famously The Three Little Pigs (1933), whose Depression-resonant chant “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” suggested we all were. In 1937, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, a quantum leap forward into feature-length animation and depth psychology, propelled Disney into a select pantheon with Griffith and Chaplin. What followed—the symphonic hallucination Fantasia (1940); the night-sea journey of a prevaricating marionette, Pinocchio (1940); the aerodynamic pachyderm Dumbo (1941), and the traumatic tale of an orphan fawn, Bambi (1942)—put him in a class by himself. The instructional work Walt Disney Pictures performed for the U.S. military during World War II—using the pliant medium of animation to help GIs read sonar, identify aircraft, and understand ballistics—earned his studio the distinction of being the only motion picture plant designated as an essential wartime industry.

Even before television stardom, Disney affected an image as a kindly overseer with a call-me-Walt managerial style. Long removed from the drone-work of cel animation, he assumed that his animators were like the seven dwarves—whistling while they worked, happy to be hunched over their drawing boards, singing hi-ho, hi-ho.11

In 1937, a man with a familiar name—Herbert K. Sorrell—entered the edenic forest to torment its benevolent game warden. Sorrell had quietly organized the Disney proletariat into the Screen Cartoonists Guild (SCG), a trade union dubbed “the Mickey Mouse Guild,” but as usual there was nothing Mickey Mouse about Sorrell’s hardball tactics.12 On May 27, 1941, the Disney family was torn apart when the SCG voted to strike and picket theaters showing Disney cartoons. Waving the best-illustrated picket signs in the history of organized labor, they demanded better wages and working hours. “I am positively convinced that Communistic agitation, leadership, and activities have brought about this strike,” Disney told his employees, it being the only possible explanation for their rejection of his “fair and equitable settlement” offer.13 Ultimately, after a bitter nine weeks, an arbitrator from the U.S. Department of Labor brokered a settlement. Disney signed a closed-shop agreement with the SCG and agreed to pay back wages to the strikers. He never forgot what he considered a betrayal from a pack of ungrateful trolls.

H. A. Smith carefully vetted and coached Disney prior to his testimony. “Mr. Disney is a gentleman, presents a nice appearance, talks well, and certainly will be an asset as a witness on our behalf,” Smith reported. But though a dedicated anti-Communist and an original officer of the MPA-PAI, Disney was a reluctant witness. “He has no fear of testifying, however he states that his story is an old one and that he is doubtful whether it would be of any value,” wrote Smith. Given the Disney demographic, the animator-mogul was considered an especially valuable catch. “We feel that in view of the type of picture which he makes his statements opposing Communism would be of material value so far as the younger generation is concerned.”14

Before taking the oath at the witness table, Disney endeared himself to two fathers on the dais. While waiting to testify, he drew cartoons of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck for a pair of delighted children who just happened to be Bunny Stripling, daughter of the chief counsel, and Jerry Wheeler, son of committee investigator William Wheeler. Bunny sat perched on Uncle Walt’s lap.

At the witness table, Disney was the factory owner not the visionary artist. He still bristled at what he saw as the plot by the Sorrell-led Communists to destroy his life’s work. According to Disney, Sorrell said “that he did not want an election and threatened a strike. He said I couldn’t stand a strike and he would make a dust bowl out of my place. I believe he was a Communist. When he pulled the strike, the first group to put me on the unfair list was the Communist front organizations.”

Disney vouched for all his current employees who, unlike the malcontents in the past, were “100 percent American.” Asked to identify the suspected Communists, Disney named David Hilberman, a former Disney artist and SCG activist; William Pomerance, former chief field officer for the NLRB and business manager for the SCG; and Maurice Howard, who in 1944 succeeded Pomerance as business manager.

“I think the industry is made up of good Americans, just like in my plant, good, solid Americans,” Disney said by way of closing. The main thing, always, was to keep the Communists from disturbing the serenity of the workers. “They get themselves closely tied up in this labor thing, so that if you try to get rid of them, they make a labor case out of it,” he said. “We must keep the American labor unions clean.”

Disney had performed as hoped and Chairman Thomas was delighted. “There is no doubt that movies are the greatest medium of entertainment in the United States and in the world,” he gushed. “You, as a creator of entertainment, are one of the greatest examples in the profession.”

At 2:30 P.M., Thomas gaveled the day to an early close.

As the dog-tired investigators and bored-to-tears spectators shuffled out of the caucus room, they could look back on an eventful week. The testimony had revealed the emergence of two camps of witnesses. Both were friendly, or pretended to be. One group—the members of the MPA-PAI and anti-Communists activists like Ayn Rand, Howard Rushmore, and Oliver Carlson—saw Communists in Hollywood as a real and present danger. The fifth columnists needed to be identified, purged, and outlawed. The other group—the moguls, the SAG presidents, past and present, and, as yet from off stage, MPAA president Eric Johnston—saw the Communists as a minor problem that Hollywood’s watchful sentinels were wise to. They were protective of Hollywood’s prerogatives and insulted by the notion that Communists had made serious inroads in the unions (thanks to IATSE) and the guilds (excepting maybe the SWG). Moreover, the minuscule percentage of Communists working in the industry had certainly gained no influence over Hollywood cinema thanks to the vigilance of the producers and the good sense of American moviegoers.

The second week, when the Unfriendlies were scheduled to take the stage, would introduce a third camp. First, however, the weekend intermission would allow all sides to regroup. The break also gave critics the chance to review the performance of the cast.