Chapter 1

Plans

“With flames on our hillsides and floods in our streets, cities cannot wait another moment to confront the climate crisis with everything we’ve got. LA is leading the charge, with a clear vision for protecting the environment and making our economy work for everyone.”

With these words, Mayor Eric Garcetti unveiled Los Angeles’ Green New Deal on April 28, 2019, a substantial augmentation of the city’s 2015 Sustainable City Plan, reflecting current research that shows the need for more aggressive action to address the climate crisis.

From phasing out Styrofoam and single-use plastics to requiring buildings to become emissions free to saving an anticipated US$16 billion in health care expenses every year by 2050, LA’s ambitious blueprint demonstrates how clear-sighted and equitable planning is allowing cities to drive the climate agenda forward, far more effectively than any other order of government.

***

Los Angeles.

Hollywood. Beaches. The Lakers of the National Basketball Association. Rolling hills. Traffic. And ... smog.

To those who grew up in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, that’s the enduring image of Los Angeles – traffic, and smog, beneath the larger- than-life Hollywood sign. Los Angeles sits in a bowl surrounded by a series of beautiful hills and mountains. It’s a heavily industrial city, and of course one with significant traffic challenges. According to reports, the air quality was so bad during and after the Second World War that consideration was given to moving the airport so pilots could see; car drivers were forced to pull over because their eyes stung so badly they couldn’t drive; and when people blew their noses, the mucus was black. On June 26, 1943, a wave of smog hit Los Angeles that was so severe that people could not see more than three blocks. Striking in midsummer, it left residents with serious stinging and burning sensations in their eyes and throats.

Frequent incidents like this led to a public reaction from local government – and eventually the state. Research work started by the County of Los Angeles, along with intense public interest, led within a few years to California legislation that permitted cities and counties to establish air-quality districts with significant powers to address the myriad causes of the disastrously dirty air – industry, backyard incineration, traffic, and many others. The City of Los Angeles and Los Angeles County created Air Quality Districts (now subsumed into the South Coast Air Quality Management District). At the time this was not easy politically; industry was bitterly opposed. Some in industry argued, for example, that the smog was caused naturally by ocean breezes bringing ozone to the city, kept in by the hills and mountains that surround Los Angeles. These theories were quickly disproven by science, which showed that an array of sources – industry, traffic, natural forces, actions by individual households – all contributed to the terrible air. This knowledge boosted a strong public campaign that led to virtually unanimous passage of the necessary legislation by the state in 1947.

These efforts were followed over time by a wide variety of measures to address air-quality challenges. While air quality even today is not pristine, it is vastly better than seventy years ago, when the issue was first addressed by local and state governments. The efforts have left legacies beyond environmental improvement – for example, the knowledge that collective action to address an environmental challenge is both possible and successful. But it needs collective will – and a plan. Action to stop air pollution in southern California has shown residents and elected officials what is possible. On air. On water. And now, on climate.

September 15, 1955: After several motorcycle couriers from the Rapid Blueprint Company in Los Angeles became ill from the effects of smog, the owners issued gas masks to protect workers from poor air quality. Source: Bettmann/Contributor.

Committed City Leadership

During an extraordinary two weeks in late April 2019, Los Angeles, New York, and Vancouver all launched climate plans whose ambition matched the requirements of science – to peak emissions by 2020 and work toward carbon neutrality by 2050. In content, these plans were about much more than just climate mitigation: both New York and Los Angeles named their plans Green New Deals in recognition that climate change is inherently unjust and that issues of equity and inclusion must be addressed by the plan if it is to succeed. Vancouver’s plan was in response to a declaration of a climate emergency by its city council. Each addressed emissions from energy, buildings, transportation, and waste, and each also addressed the fundamental inequity involved in climate change – caused by the wealthy few, its impacts are felt first by the poorest in a city, then globally. Each of these bold plans sought to ensure that the least well off in their communities would benefit from the efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

In Los Angeles, which owns the electric utility (the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power or LADWP), the plan focused first on generating zero-emission electricity by closing the remaining natural gas plants in Los Angeles and replacing them with clean energy. It then outlines a move to electric transport and electric heating and cooling of buildings using the clean grid – and has strong measures to move toward zero waste and zero waste of water.

New York analyzed its emissions and identified buildings as its priority, implementing a plan with mandatory measures for the reduction of carbon emissions in large buildings. Vancouver, in a Canadian province with a clean-energy grid, built on this strength with measures to promote a city where it is possible to live well without owning a car by supporting new public transport, walking, and cycling, and has ground-breaking legislation to dramatically reduce the carbon emissions of new buildings.

Why Plans?

To successfully mitigate emissions, the need for a climate plan is both obvious and subtle. As we have seen, planning is an integral part of the role of city governments. Mayors understand the strategic importance of plans, and complex organizations such as the civil service of a large city operate based on the instructions in city plans. Those instructions are even more essential for an issue such as climate change; that is, complex problems whose resolutions require coordinated action by many city departments and agencies – who might see climate action as outside their responsibility.

When I was still in office as mayor of Toronto, we instituted a program as part of our climate plan to encourage the installation of solar thermal hot-water heaters, which, on a south-facing roof, work surprisingly well in our climate. The program was part of a suite of measures adopted by city council to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels at the household level, and the heaters used sunlight to warm water for household use, displacing the natural-gas water heaters most common here. At the program launch at a house in the east end of Toronto, just before we took questions from the dozens of reporters and numerous television and radio stations, the local councilor leaned over to me and whispered in my ear, “I think you need to know, the plumbing department has refused to grant permits to solar hot- water heaters, including this one.” It turned out that despite a bylaw from council authorizing the installation of solar thermal heating on single-family homes, the plumbing department took the view that until the bylaw governing its responsibilities also was changed it could not authorize the work! Fortunately no one in the press conference thought to ask if the installation had a plumbing permit.

A climate plan starts by measuring the amounts and sources of greenhouse gas in a city – known as an emissions inventory. It is critical to measure emissions so that the biggest sources can be addressed with accurate knowledge and steps to address them can be set out logically in a written document. But in a city-government context, the existence of a plan is equally important because it forces the system – the various departments and agencies – to act by incorporating climate actions into the everyday routine work. It is only in this way that a plan can be successfully implemented, and experience has shown that to mobilize these departments (who might not think climate change is their job), it is essential to prescribe goals for them and include them in the development of a plan. In this way, the plan gains from expert input – but also gains the confidence and personal commitment of those well beyond the city’s environment department.

City governments are complicated organizations. They have jurisdiction over matters highly relevant to climate policy, such as parks and trees, buildings, transportation, roads, water, and wastewater. Historically and typically, these areas are administered by city departments heavily focused on those specific responsibilities. So, for example, the transportation department is typically focused on roads; a transit agency on transit; and the finance department on budget and financial oversight. Environmental matters, especially climate change, tend to cross all departments. To take advantage of opportunities and be successful in mobilizing the significant city resources in the same direction, it’s necessary to have a plan that everyone is obliged to follow.

What Do Plans Need to Do?

In 2015, the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and Arup engineers asked the question “What needs to be done by the largest cities in order to do their share to help the world avoid dangerous climate change?” In climate shorthand, this is known as a “1.5 degree” world – which means holding overall global average temperature to an increase of no more than 1.5 degrees. This is now generally accepted as necessary to avoid the most catastrophic elements of climate change and is highlighted by the science underlying the latest reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (and even those issued by the White House).

The Arup research showed that to do their share, cities in the developed world needed to peak their emissions by 2020, more or less halve them by 2030, on a trajectory to carbon neutrality by 2050. (The peak could be a little later in the developing world but the trajectory has to be the same.) The C40 calls this Deadline 2020 (D2020), and so far more than one hundred major global cities have announced that they will produce D2020-compliant plans.

One of the important strategies used by mayors to address climate change is international collaboration. The C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, of which I was chair from 2008 to 2010, was started by London mayor Ken Livingstone in 2005. Mayor Livingstone saw that the world was not acting quickly enough on climate change and believed that the voices of the mayors of the world’s major cities could, in a significant and positive way, affect international action on climate. In addition, their actions, when multiplied at scale, could meaningfully reduce global emissions. Today, the C40 has ninety-four members, who represent city-regions with more than 750 million people, a huge portion of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, and 25 per cent of the world’s economy. Their actions have global implications.

Since inception, the organization has been enormously influential and has placed cities squarely at the heart of international conversations on climate. The actions by its members – global cities such as Johannesburg, Tokyo, Cape Town, London, Beijing, Rio, and Paris – collectively are making a difference to climate already, and the best of these actions, if undertaken globally at scale, will make an immediate and lasting major difference. The current chair is Mayor Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles, a recognized climate leader in his own right.

Importantly, these cities have shown that city plans can work. The most successful have shown that it is possible to achieve dramatic carbon reductions while enhancing the life of residents of the city and helping the city to prosper. In fact, in almost every case, strong climate plans are being made and implemented simultaneously with strong economic prosperity in these cities.

Do City Plans Make a Difference?

Can the world’s major cities save the planet entirely on their own? Perhaps not – although, as stated in the preface, C40’s studies show that about 70 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed to cities, generally in the areas of waste management, transportation, buildings, and electricity generation. (These figures are known as scope-two emissions; that is, emissions accounted for by city activities even if they don’t occur physically within the city. For example, the greenhouse gas emissions of a coal-fired electricity plant to supply electricity to a city would be included in this measure, even if the plant were located outside the city boundaries.)

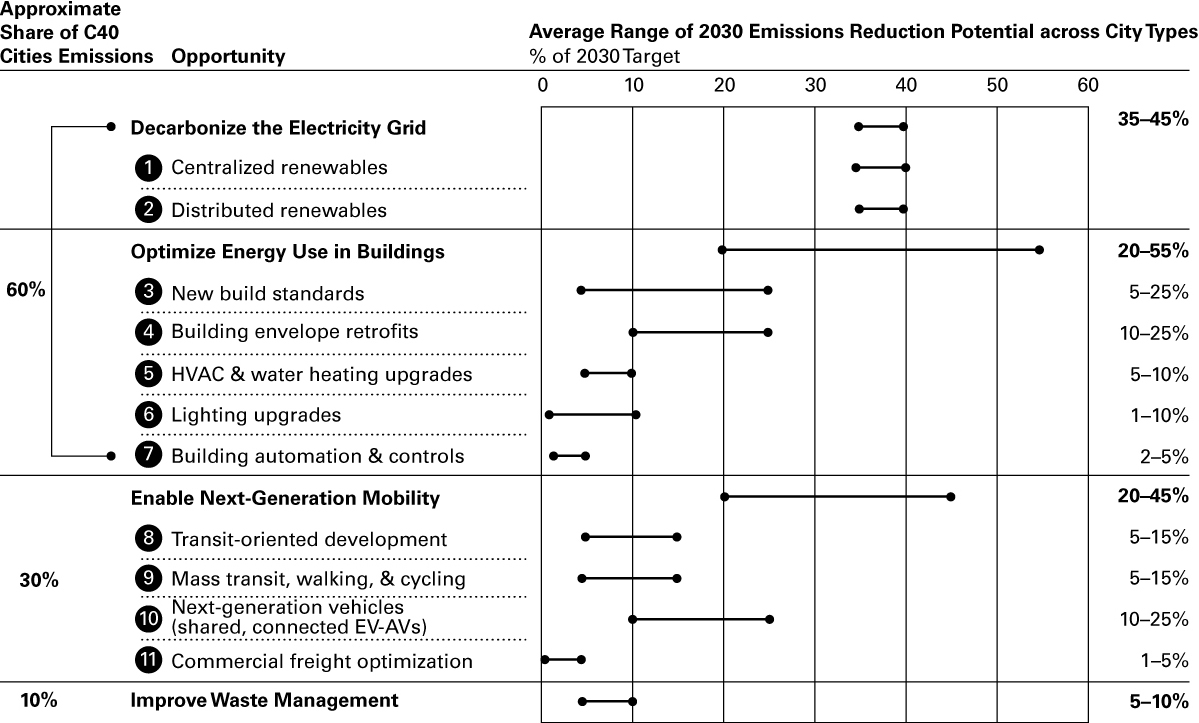

Further studies have demonstrated where cities need to focus. Both the Coalition for Urban Transitions’ report, released in September 2019, and the McKinsey Center for Business and the Environment’s Focused Acceleration report (2017) clearly demonstrate that city leadership can make huge advances if city actions focus on those priorities of electricity, buildings, transportation, and waste management. Figure 1.1 is a chart from McKinsey that measures the most significant outcomes and their likely impacts. The ranges depend on city types as defined in the report (i.e., dense like New York, spread out like Houston, dense like a major city in the developing world, etc.).

Figure 1.1: Effectiveness of City Actions

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of city actions in reducing greenhouse gases when focus is placed on electricity, buildings, transportation, and waste management. Source: Exhibit from A Strategic Approach to Climate Action in Cities - Focused Acceleration , November 2017, McKinsey & Company, www.mckinsey.com. Copyright © 2020 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

Will these plans work? The answer is a resounding yes. Good examples can come from my home city of Toronto as well as Oslo in Norway. Both cities are in oil-producing countries. Toronto is Canada’s biggest city with a heavy industrial heritage (albeit a city where much of the manufacturing base has moved to the suburbs, the United States, Mexico, or China). The city remains the economic heart of Canada, being home to five of the six major banks, head offices of most insurance companies and investment houses, significant information-technology companies, film, television and media companies, and construction and development companies, and is still home to a significant food-manufacturing sector.

Proven Effective: Toronto’s “Change Is in the Air”

Toronto’s path to dramatic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions demonstrates what is possible and can be undertaken by any large city. What did Toronto do? Conceptually, it was simple. It set greenhouse gas reduction targets based on the Kyoto Protocol, measured Toronto’s sources of emissions, and developed a plan to address those sources. The plan required re-evaluation over time, thereby providing an opportunity to assess both progress and the state of scientific knowledge about climate change. The first plan, “Change Is in the Air,” was adopted unanimously by Toronto city council in 2007.

It’s important to understand the elements that allowed Toronto to pass an ambitious climate strategy. First of all was a strong political culture. Toronto has a history of action on environmental matters, and residents both expect and demand that their city councilors and mayor show leadership.

But success in getting a plan through city council and adopted as legislation is only the first step. Toronto’s work in developing the plan shows that there are several important steps to developing a strong and resilient plan with a good likelihood of success. First, there was good collaboration between the political arm, through the office of the mayor, and the civil service in the development of the plan. Second, the plan covered a significant range of actions, very few of which could dramatically decrease greenhouse gas emissions on their own but taken together could have a powerful impact. Third, the plan had clear targets and goals and was based on a comprehensive emissions inventory. Finally, the plan consciously brought together different departments and areas of the city to ensure collaboration in both the plan’s development and delivery.

The plan contained more than 120 actions in the areas of transportation, buildings, and waste management. It engaged residents and built on partnerships with public and private institutions. It was helped by the provincial government’s closure of the Lakeview coal-fired power plant in 2005, which, while located outside Toronto, supplied significant amounts of electricity to the city – which resulted in a significant and permanent reduction of emissions.

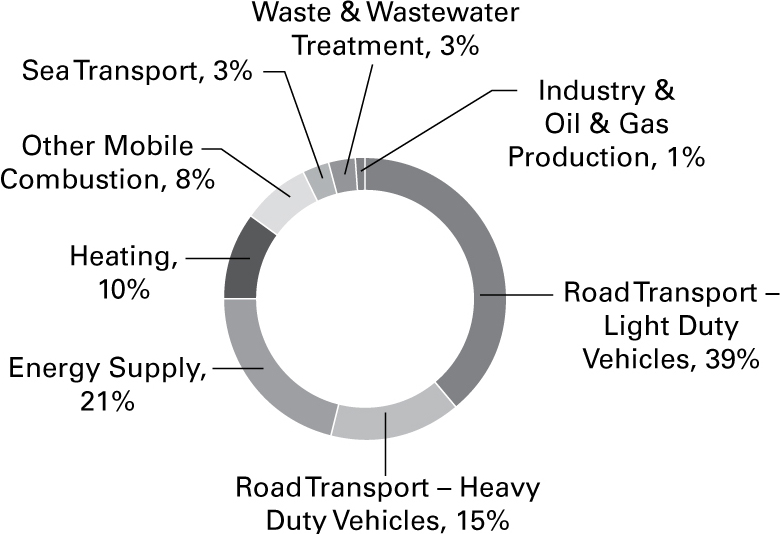

While not all the actions envisioned in the plan proceeded at the scale hoped – for example, the ambitious rapid transit expansion strategy known as Transit City has not proceeded at the pace expected – the city achieved its goals and had reduced greenhouse gas emissions in the Toronto geographic area by 15 per cent by 2012, as demonstrated by an external evaluation. A second evaluation, using 2017 data and reported in 2018, showed that Toronto is now 33 per cent below 1990 levels of greenhouse gas emissions, and a new plan was adopted by council to strengthen progress. The 2016 emissions are shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Toronto’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 2016

The major sources of greenhouse gas emissions in Toronto match those of most cities, which collectively account for 70 per cent of worldwide emissions. Source: Based on data from City of Toronto, Transform T.O. Report 1: Short-Term Strategies, 2016, November 2016.

A typical criticism from those seeking to thwart climate action is that taking such action hurts the economy. This is a false argument: the real costs of climate change are the costs of inaction (for instance, the billions in damage caused by the increasing frequency and severity of storms are real and result in substantial costs to governments, insurers, people, and business). The economy of Toronto proves the point. Since the passage in 2007 of its first climate plan, employment in the city of Toronto has increased significantly: according to the Conference Board of Canada, growth in Toronto has considerably exceeded national averages at least since 2009. The average house price nearly doubled between 2007 and 2017 (in fact, like many other North American cities, the challenge facing Toronto has been one of affordability due to increased housing costs.)

I am not arguing that the city’s efforts to address climate change have directly caused the strong economic activity, as I have not seen a study that validates that point. However, it is clear from the Toronto example that strong action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions does not inhibit economic prosperity as argued by leading figures from conservative political movements and some parts of the fossil fuel industry. Such an argument does not stand up to any scrutiny whatsoever.

The Next Frontier: Oslo and City-Based Carbon Budgets

While Toronto remains an excellent example of leadership in the North American context, Oslo, the capital of Norway, has gone even further. In addition to developing an emissions inventory (see Figure 1.3), a plan, and actions to address greenhouse gas emissions, Oslo has also introduced a carbon budget.

Figure 1.3: Oslo’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 2016

Oslo’s implementation of a carbon budget allows it to address greenhouse gas emissions from all sectors as a primary element of planning. Source: Based on data from Norwegian Environment Agency, 2018.

The Oslo carbon budget is fascinating and is the world’s leading example of how to integrate greenhouse gas emission reduction into the basics of government planning.

Oslo has ambitious goals for carbon reduction:

• 36 per cent below 1990 levels by 2020

• 50 per cent below by 2022

• 95 per cent below by 2030

Electricity is currently 98 per cent from hydro – which means that the electrification of heating and transportation is clean and likely to reduce greenhouse gas emissions significantly.

Oslo’s climate budget is treated as a part of the city budget and is passed as a chapter in that budget with a debate and vote by city council. The budget is adopted annually and is managed by the finance department, a subtle but important matter. It may not be obvious that the finance department should be responsible for greenhouse gas emissions, but this administrative detail is of critical importance. Finance touches all city departments, and there are recognized approval and administrative structures overseen by finance for the financial budget that can be adopted for a carbon budget. City departments are familiar with these approval processes, which means a direct operational integration of climate and energy strategy into the city’s administrative operations – and recognized accountability measures.

All city departments are responsible for proposing measures and for implementing the actions. For each measure and action, the designated responsible department or agency must track and report on progress three times annually so changes can be undertaken if required. Importantly, council has directed that the city cannot generate more CO2 than budgeted – period.

As it is not always possible to precisely measure emissions as they occur – to give a simple example, live monitoring of vehicle exhaust does not exist – simple and reliable indicators are used by city departments. In this example, the number of vehicles passing through toll gates or the rate of e-vehicle adoption would be used to create data sufficient to judge whether emissions from transportation would increase or decrease as a result of a proposed measure’s implementation.

The most significant factor, though, is not in these implementation details – effective as they are – but in the fact of the carbon budget itself. A city department cannot undertake a project without considering greenhouse gases in the same way that the department cannot undertake a project without considering the necessary financial resources. If the recreation department wanted to build a new curling rink for a community center, it would need to consider energy sources, insulation, and so on in the same way it would have traditionally considered cost. This remarkable and simple mechanism forces a department to directly address its environmental footprint – analogous to the existence of a plan forcing the department to consider that issue as part of its operations, but more directly effective because it is mandated. And that mandate has direct impacts in the critical areas for Oslo of buildings, transportation, and waste management.

Oslo performs one other action extremely well as part of its climate plan: storytelling. Oslo tells positive stories of how people live better lives with climate action in order to promote even greater action. It avoids negative messaging and focuses on changing behavior rather than attitudes. The Oslo website regularly features stories about climate actions – for example, “We haven’t regretted even for one second switching to an electric van” or “It’s great that this electric bus is so quiet to drive.” The city provides educational material for schools and has developed the Oslo Centre for Urban Ecology to engage citizens in ecological work in the city, encourage local environmental and climate measures, and “help the city’s residents to feel a sense of ownership over, and see the potential in, the shift toward becoming a zero-emissions society.”

Making Plans Equitable and Fair: Inclusive Climate Action

This book argues that actions in leading cities to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the areas of energy, buildings, transportation, and waste have the potential to help the world solve the climate crisis. By replicating these actions at scale – for example, all cities mandating electric taxis, such as Shenzhen, China, has – greenhouse gas emissions globally can be dramatically reduced, and the city involved can become a better place to live. By demonstrating that climate action works, city leadership can overcome the biggest challenges to solving the climate crisis: inertia and the perception that measures to address climate change make people’s lives more expensive, more difficult, or worse.

One of the advantages of city governments in almost every country is that they have a strong connection with their residents: the responsibilities of city governments require direct connection to residents, as city councilors typically have much smaller districts than regional or national politicians, and residents identify strongly with where they live. Consequently, this has tended to mean that cities have developed a strength in public engagement – and a resulting strength in public trust.

In the context of climate, this trust is significant as it is a critical asset for cities and their mayors in leading change. At the same time, the strong connections to residents ensure that cities often recognize issues well before national governments do. As a result, mayors increasingly are seeing the connection between equity – inclusivity – and their political ability to act on climate.

Climate change is unfair. The majority of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions have been caused in support of the lives of the most well off, but its impact tends to be felt most by the least well off, both globally and within particular cities. Fairness requires that the needs of the least well off be made a priority when addressing climate change, and politics requires the same. The inherent inequity in the impact of climate change has the potential to derail efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions unless the needs of the most vulnerable are included in the climate plan and the residents themselves included in the planning.

A number of global cities have prioritized inclusivity in their climate plans and have created pilot projects. While solutions are not so easily transferable from city to city as many other climate actions, the underlying principles are clear: include low-income people in your climate planning, then listen to and act on their needs. Address air quality, health, and other issues at the same time as reducing greenhouse gases. Create jobs and opportunity. Make living less expensive and the quality of life better for the least well off.

In the same way that climate actions can spread from city to city, these good ideas can as well. For example, inclusion of process is a principle that all cities can follow – perhaps in different ways, but the underlying principle is the same. Paris and Barcelona are examples of what is possible when engaging residents in climate planning, listening to their concerns, and acting.

“Today, cities and nations alike have the opportunity to build on the momentum created in Paris. We have the opportunity to put the world on a low-carbon pathway. Let us seize it.”

– Mayor Eduardo Paes (Rio), April 2016

Participatory Budgets in Paris

In 2014 Paris began a process of participatory budgeting. Participatory budgeting means giving residents the right to make some (or all) of the decisions about spending priorities for a city government. The city committed to setting aside €500 million, or about 5 per cent of its total spending, for allocation through participatory budgeting between 2014 and 2020. The city has specified that at least 20 per cent of these funds should address climate issues. This participatory budgeting process has engaged nearly 200,000 residents, with the intention of building a stronger relationship between city hall and residents – and with the potential of meeting the needs of residents as expressed by them.

Building on its experience in participatory budgeting, Paris listened to the needs that residents expressed. In its approach to climate planning Paris put its focus on fuel poverty (defined as households that spent more than 10 per cent of their income on heating and cooling residences), which it sought to address by a combination of subsidies, energy retrofits, and assistance to residents in learning how to better manage home energy consumption.

Accordingly, Paris has an extensive program of energy retrofits in its publicly owned housing. Building on this program, Paris made alleviating fuel poverty a specific goal of the climate-action plan, with the objective of undertaking energy retrofits on five thousand apartments annually. As a result, Paris has already seen a reduction in the energy demand in these buildings and a significant decrease in the number of residents seeking subsidies – making residents economically better off and addressing the sources of greenhouse gases at the same time.

Environmental Justice in Barcelona

Barcelona expressed similar principles in the development of its climate plan. Its 2018 climate plan had an environmental justice and “citizen co-production” focus, allowing the plan to address economic and social inequality at the same time as it addressed climate mitigation and adaptation. To successfully undertake such measures, Barcelona recognized that it was essential to engage the residents of low-income neighborhoods and others vulnerable to the impacts of climate change in the plan’s development. This engagement provides city authorities with a greater understanding of the needs of the most vulnerable and the potential solutions – and with a chance to demonstrate that people have a real say over the decisions that affect their lives.

Barcelona built an extensive community-engagement process that deliberately reached beyond those who might normally be engaged in an environmental consultation. The city worked closely with those who already were working with low-income neighborhoods or with other vulnerable groups, such as nongovernmental organizations, social associations, and private businesses. The city recognized an important fact that would be true in most places – those most affected by climate change might well not be those who participate in public discussions. Low-income residents of a city, by definition, tend to be both excluded from power and the manifestations of power – such as direct engagement with government – and preoccupied with ensuring their own economic survival. In this context, special efforts must be made to connect with low-income and other disempowered residents; otherwise, their voices will not be part of the conversation, and any solutions developed will likely not meet their needs.

Accordingly, Barcelona ran a lengthy (six months) process in 2017 to engage representatives from partner organizations and residents at an early stage of the climate-planning process and followed up with a presentation of the plan in February 2018. Barcelona has reported that 85 per cent of the recommendations received during this process were incorporated into the plan – demonstrating to those affected and participating that their voices mattered and strengthening the plan by virtue of the recommendations.

Barcelona’s climate plan explicitly addresses equity issues and can be a model for others. Previous work by the city, such as the 2016 health survey, had demonstrated significant connections between the impact of climate change and poverty – ranging from issues such as energy poverty to the differential effects of heat and rising temperatures on the elderly, the young, and women. As a result, Barcelona’s climate plan included a series of actions that would particularly benefit the most vulnerable residents. Consistent with many other cities, Barcelona’s climate plan is well organized thematically and consists of very specific actions grouped into thematic areas: 1) people first, 2) starting at home, 3) transforming communal spaces, 4) climate economy, and 5) building together. The plan is structured with “plans of action” according to the themes and then more than two hundred specific actions. For instance, the theme of “people first” has plans of action for improving and adapting services, facilities, and homes for the most vulnerable; for preventing gas, water, or electricity from being cut off; and for preventing harm from excessive heat.

Barcelona detailed at the outset quite specific actions to achieve these goals. For example, as part of the “preventing excessive heat” plan, the city’s goal is to ensure that all of the population is within a ten-minute walk of a climate shelter by 2030. Consequently, the city is mapping all potential places where people could find refuge – from libraries to air-conditioned malls, to parks with significant shade cover – and considering issues such as availability at different times of the day, physical accessibility, etc. This information will be used to identify gaps in available facilities and decide where new facilities might be created.

More famous are the Barcelona “superblocks” – an urban- planning idea that has changed the way districts are organized. Barcelona has prioritized the movement of people over vehicles by making local streets in a neighborhood – or superblock – virtually car free (local traffic only), while enhancing amenities for pedestrians – such as tree cover and benches. While controversial at inception, the superblocks have proven popular since implemented, as they have improved local quality of life, personal mobility, air quality – and local economic activity. While the original superblock plan lowers emissions from automobile traffic, Barcelona has used the concept of superblocks in its climate plan to help build social resilience as well. The city has organized home-care social workers on a similar (but not necessarily identical) basis to assist dependent residents – such as the elderly – by ensuring that the same social workers regularly visit and become part of the trusted fabric of the neighborhood. These workers will be available to assist with climate matters – such as reducing energy expenditure and coping with extreme heat events – as well as more traditional forms of assistance, all the while supporting the building of a sense of community and social cohesion.

Starting with an inclusive process is critical: if low-income and other marginalized residents are not heard from directly, it is far less likely that a climate plan will address their needs. As we have seen from both Barcelona and Paris, an inclusive process can help lead to inclusive outcomes. These can move far beyond energy issues: economic security and health impacts of poor environmental conditions are both issues raised during public outreach. And cities are addressing these issues – systematically and effectively.

“We are disconnecting the oligopolies and connecting to renewables, to self-sufficiency and energy control.”

– Mayor Ada Colau (Barcelona), May 2019

The Final Word

The best city climate plans reduce greenhouse gas emissions effectively, in line with scientific requirements to hold overall temperature rise to 1.5 degrees. The best climate plans also do something else: they address issues of prosperity, health, and inclusion, thereby putting cities in a unique position to deliver on both meaningful climate action and social justice.