Chapter 5

Public Transportation

London’s underground map is so iconic that it adorns T-shirts of youth worldwide. Paris, Berlin, New York, Chicago, Tokyo – all cities with significant rail-based mass transit that serves their residents well and that can support the kind of density necessary to create environmentally and economically efficient cities. These cities, each with excellent subway systems, show how much public transportation matters – to meeting the transportation needs of residents, to the city’s economic success, to air quality, to equity and inclusivity. Transportation also matters very much to climate change. It is a critical source of greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in cities. Typically, dense, built-up cities with excellent public transit systems tend to be places where relatively more people take transit and fewer drive – and consequently, greenhouse gas emissions are lower.

But subways are not the only way to successfully move vast numbers of people quickly and efficiently – a lesson from Curitiba, Brazil.

Curitiba is a city of nearly two million people in the south of Brazil and is the capital of the state of Paraná. Not nearly as well known to those outside Brazil as Rio de Janeiro or Sao Paulo, it is nonetheless important economically and socially. It is home to the University of Paraná, to significant manufacturing and food processing, and to industries such as paper and wood processing. At least since 1940, the economy of Curitiba has been strong and growing, powered by both external and internal migration – so much that more than half of its current residents were not born in the city.

It has also been home to a visionary and effective mayor, Jaime Lerner, who was mayor for three separate terms between 1971 and 1992, and then governor of the state for two more. Mayor Lerner is known for building new parks and lakes, for making the city center walkable, for a strong belief in equity – and among those who study public transportation, for the revolution in public transportation he introduced in his third term as mayor. Not by subway, but by bus.

***

Dense Cities Are Good for the Environment

How does a city need to be built? From an environmental perspective, and increasingly from an economic-efficiency and social-inclusion perspective, cities are trying to make themselves places where residents can live without having to own a car. In the longer term, it is possible to build cities that promote transit use and active transportation – walking and cycling – over driving. We see this in cities as varied as New York, Tokyo, and Copenhagen, where density (in the cases of New York and Tokyo) or effective planning (in the case of Copenhagen) have resulted in cities with high rates of transit ridership, walking, and cycling. In these, and similar cities, statistics (known as modal share) show that residents favor transit or active transportation. They demonstrate that it is possible to build cities that meet the transportation needs of all residents, while helping to create healthier places to live. Of the people who live and work in Manhattan, only 5 per cent drive to work – 42 per cent take the subway or bus, and the majority walk, ride, take a taxi, or do something else. In Copenhagen, the split in favor of active transportation is even more dramatic – more than 40 per cent of residents commute by bicycle.

There is a popular image that shows how much space is taken up by sixty people occupying individual cars versus the considerably smaller space taken up by those same sixty people contained in a bus or on bicycles. That comparison demonstrates one reason for the success of transit, walking, and cycling matter: using limited space in cities for active transportation is far more efficient than any alternatives – and public transportation is far more efficient than cars.

The gold standard in public transportation can be found in cities such as Tokyo, Berlin, and New York, where density and history have combined to create networks of regional rail, subways, streetcars, and buses that enable virtually anyone to access reliable, inexpensive, and quick public transport. Particularly when powered by clean electricity grids, rail-based transit is highly advantageous from an environmental perspective. Build it (a network), and they will come – out of their cars and onto transit.

Transit networks have other advantages for cities. They make dense urban development possible and – given that economic studies clearly show that dense urban environments are more productive – help to create jobs and prosperity. They help address inequality, by not requiring people to own and pay for expensive vehicles to participate in social and economic life. They help to address air quality and other local health issues – and, of course, they help to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

New Rail-Based Rapid Transit in Unlikely Places

Cities in Europe such as Berlin and Paris long ago built excellent rail, metro, tram (light rail transit), and bus networks that allow people to live far more sustainable lives because they do not have to use a car to partake of the life of the city. This is true elsewhere – such as New York and Tokyo, Chicago and Toronto, Montreal and Milan. All these cities have benefitted economically too, as the density possible from permanent rail transit has helped create significant wealth over time. It would benefit many other cities if they built subways and light rail transit (LRT) – and we know that’s possible, from examples as varied as Los Angeles and Addis Ababa.

Los Angeles

Today we can see exciting examples of cities building more public transport to help residents more easily choose rapid transit. In the County of Los Angeles (which includes the city and surrounding region), nearly 70 per cent of residents voted for Measure M in 2016, a sales tax increase ballot proposition with substantial funding for transit projects, walking, and cycling. The funds will allow for a significant increase in subway and light rail lines and additional busways to create a massive expansion to the region’s network. In a city noted for its devotion to cars, it is telling that a tax increase to fund transit and active transportation so overwhelmingly passed. And the City of Los Angeles plans to ensure that significant portions of this work are fully complete by 2028 – in time for the LA Olympic Games.

Addis Ababa

The East African country of Ethiopia is located in a hilly region just west of the Horn of Africa. Its capital, Addis Ababa, is a modern metropolitan city with a population of more than three million inhabitants and rising fast: by 2037 it is projected to be ten million. It is dubbed the political capital of Africa as many international organizations are headquartered there, including the African Union and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Addis Ababa struggles with high poverty rates, large informal settlements, and other challenges common to major African cities.

As of 2016, transportation was responsible for nearly half of the city’s greenhouse gas emissions. On a global scale the city’s emissions are relatively low – the average European city creates sixty times the amount of emissions. But Addis Ababa does not want to create a problem as it grows and is looking to manage greenhouse gas emissions well. For economic as well as environmental reasons, the city is planning to become more compact and connected. Its plans include a commitment to transit-oriented development – building around and near transit lines and stations.

Addis Ababa’s population currently gets around largely by foot. Roughly 60 per cent of residents walk to their destinations. As the city grows, incomes increase, and livelihoods change, residents will probably increasingly seek other ways to get around. That means more transportation infrastructure and, if based on the automobile, more congestion and more emissions. Roads are congested today, and the vehicles are older and highly polluting.

An efficient and affordable public transportation system is essential for Addis Ababa’s social and economic development. As the city’s population grows, the poorest find themselves at the edge of the city, where lack of transportation options means lack of access to jobs and opportunities for socioeconomic mobility. For these and other reasons, in 2015 Addis Ababa became the first sub-Saharan African city to develop an LRT system. (LRT systems are rail-based electric transit systems that have their own right of way and typically use European-style tram technology, rather than “heavy rail” – larger and heavier vehicles used in subways.) The two-line system carries up to sixty thousand passengers per hour and regularly reaches full capacity. In a congested city where road traffic travels at an average speed of ten kilometers per hour (about 6 miles per hour), the LRT is a welcome alternative with average speeds of twenty-two kilometers per hour (about 13 to 14 miles per hour).

Ethiopia’s electricity comes almost exclusively from hydropower. As a result, this system has zero operational emissions. In 2015, the city’s calculations showed that the LRT in Addis Ababa eliminated significant amounts of carbon dioxide (55 kilotons), a value projected to grow to 170 per year by 2030.

Modern, sleek, and effective light rail in Addis Ababa – like an above-ground subway. Source: Goddard_Photography/iStockphoto.com.

The LRT is indeed helping to develop a more compact and connected city. Areas close to LRT stations are seeing increased development. In some areas of the city, buildings are being torn down, and new, taller buildings are taking their place. The condominiums and multifamily housing that are appearing allow for far greater population densities, but as in western cities, there is a risk that the lowest-income inhabitants cannot afford this new housing and will need to live farther and farther from the city center, a consequence that would be explicitly contrary to the intent of the proponents of these changes.

The LRT system was largely paid for with concession loans from the Export-Import Bank of China. Operation and maintenance responsibilities were shared between Ethiopian and Chinese companies. Ethiopian workers were trained to operate and manage the LRT and gradually took over full management of the system.

The financing has been a challenge – repaying loans while keeping fares low is a difficult juggling act – but ridership is very high: clear evidence of a need for clean electric mass transit in a large developing city.

From a climate perspective, we don’t have to wait for cities to find the resources and leadership to massively expand subways and light rail – there are numerous steps that can be taken in the short term that make a very real difference in providing better transit and lowering emissions immediately. Building or expanding a network as Los Angeles is doing will take time – which gives rise to a question: How can public transport be used to dramatically lower greenhouse gas emissions in the short term, as we plan and build the networks our cities and their residents need in the longer term?

“The first article in every constitution in the world says that all citizens are equal before the law. This may sound like a nicety, but it is actually a very powerful statement. Because if citizens are equal before the law, a bus with 100 or 150 passengers should have the right to 150 times more road space than a car with one person.”

– Mayor Enrique Peñalosa (Bogota), International Transport Forum, 2011

Frugal and Effective: Bus Rapid Transit

The answer is the bus – sometimes considered the lowly bus. But buses are a critical part of the transportation solution for global cities. In 2017, it was estimated that there were approximately three million buses in municipal fleets across the world. To meet urban transport needs and address climate challenges, we need more – and better – buses. Bus rapid transit powered by clean electric buses has the power to both increase the relative use of transit in a city and to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transit. McKinsey tells us that greenhouse gases can be reduced by these advances – up to 25 per cent – advances that are feasible in most world cities today at relatively low cost and that are quickly achievable, in line with the urgency needed to act on the climate crisis.

Under the leadership of Mayor Lerner, in the 1970s the City of Curitiba took a bold step to address its transportation challenges. At that time Curitiba was in the midst of a growth spurt that continues to this day, and the rapid population expansion had driven planners at the state level to suggest solutions that were popular at the time – more and wider roads, and subways underneath. Mayor Lerner, an architect by profession, saw things differently.

“A system of bus rapid transit is not only dedicated lanes. You have to have really good boarding conditions – that means paying before entering the bus and boarding at the same level. And at the same time having a good schedule and frequency.”

– Mayor Jaime Lerner (Curitiba), 2011

He saw potential in the bus and designed a system that used the advantages of rail systems – permanent infrastructure and its own right of way – but integrated this infrastructure along the city’s main arteries. This allowed the buses to operate at speeds similar to light rail, at a fraction of the cost, and – equally importantly – allowed the system to be built in a fraction of the time it would have taken to build a subway system. Gradually, the bus system became highly successful, carrying huge ridership (more than 2.4 million people, as of the latest available ridership figures).

The easy boarding system that helped transform Curitiba by turning a bus into rapid transit. Note how the doors facilitate easy loading and unloading, making the service efficient and effective. Source: tupungato/iStockphoto.com.

In 1991, in his third term as mayor, Lerner added a distinctive feature designed to dramatically lower boarding times and thereby improve service – new tube-like stations where riders pay before they board. The stations also allow for access to the buses for riders with mobility difficulties, including those in wheelchairs. With the addition of these new stations, buses were able to provide exceptional service – on some routes, there is a bus every ninety seconds. Many give the mayor credit for creating the first bus rapid transit (BRT) system in the world.

This idea has proven to be successful. Bogota, the capital of Colombia and a busy city with its own historical challenges, decided to build a BRT (the TransMilenio) based on Curitiba’s system. The city argued that a full system could be designed and built at about the cost of one short subway line, and in 2001 the Bogota BRT was opened. Like Curitiba, passengers board from raised platforms and pay before boarding. The system is accessible for people with wheelchairs and has both express and local services. As was the case in Curitiba, routes were planned to spur prosperity in economically deprived neighborhoods. The city also measures air quality, randomly testing buses each day to ensure standards are met.

This movement is not restricted to South America – Addis Ababa itself is also adding a BRT system to complement the LRT. One sixteen-kilometer (ten-mile) corridor is under development, and six others are planned for development by 2030. This system is expected to be faster, more comfortable, safer, more reliable, more accessible for those with physical challenges, and produce lower levels of emissions relative to the minibuses that are used now.

In Addis Ababa, early and extensive public and stakeholder consultations were essential to help the city understand possible impacts of the changes and to help residents plan for and embrace the new LRT and BRT systems. Drivers and owners of the minibuses whose routes will be displaced by the new BRT system, for example, have legitimate concerns about loss of income and livelihoods. The city has therefore been working to employ displaced workers in its BRT system and to offer shareholder positions in the bus-operating company to minibus operators.

Addis Ababa carried out extensive research on LRT and BRT systems in other cities before embarking on its own projects. Learning from the experience of others allowed the city to avoid a number of the pitfalls and obstacles that other cities have encountered. A dismantled BRT system in Delhi, for example, showed the need for properly designed terminals and coordinated marketing and information campaigns. As Addis Ababa rolls out its own BRT, the system will itself become a model and learning opportunity for other developing cities. Indeed, C40 Cities predicts that the public transportation system will be a “blueprint for local expansion and regional replication.” As the first LRT plus BRT in sub-Saharan Africa, the system in Addis Ababa sets an exceptionally important precedent for other African cities for how to build transit that provides personal mobility without reliance on the automobile and its related pollution.

Buy More Buses

We need more buses if we are to move people efficiently to where they need to go – buses are cheap and effective. Often an increase in bus service in a built-up city – or a small town – can be accomplished when other projects would take significant time due to cost and complexity. For example, between 2003 and 2010 Toronto adopted a strategy focused on increased bus service and better value (allowing the unlimited-use pass then named the Metropass to be used by multiple family members) to dramatically increase transit ridership.

Toronto is a large built-up city of nearly three million people in the heart of an urban region of about six million. While it has a built-up and dense urban core reminiscent of Chicago or Manhattan, it’s also a city with a spread-out set of inner suburbs designed not for transit but for the car. While the city has an excellent transit service, the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC), its core rapid transit – subway and streetcar – is really designed to serve a city of half the size. Over time, while new rapid transit projects are being built, significant practical reliance on buses continues. Some of Toronto’s bus routes are exceptionally busy – for example, the Finch West bus route that serves the northwest inner suburbs of the city has more than forty thousand riders a day, making it one of the busiest transit routes in North America. To give some perspective, that’s about 25 per cent of the entire ridership of Boston’s Green Line light rail/ subway system.

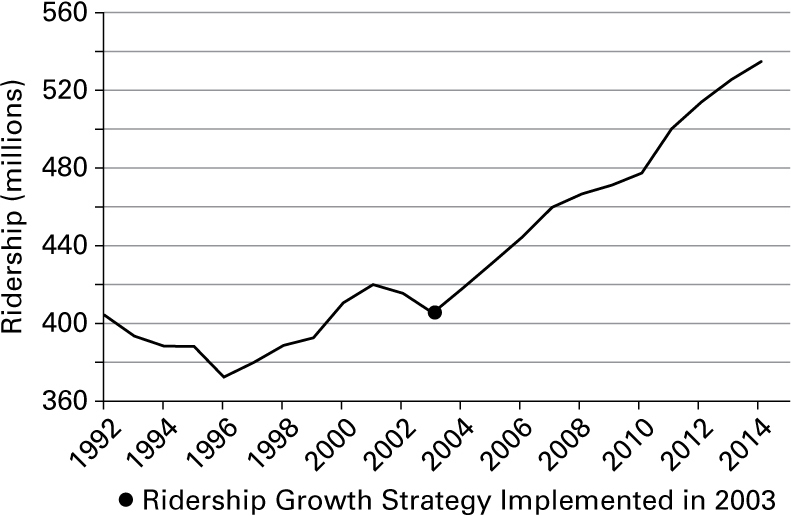

In 2003 and 2004 the TTC recognized the potential of improved bus service by adopting and implementing the Ridership Growth Strategy. A commitment was made to riders that there would be bus service within one hundred meters (about 110 yards) of every residence, and at least fifteen-minute service on all routes until 2 a.m. Service on the existing network of night buses and streetcars was improved, and new routes added to ensure reasonable twenty-four-hour access to bus service citywide. This drove significant ridership gains, as shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1: TTC Annual Ridership, 1992– 2014

Toronto showed that simple strategies can drive significant ridership growth. Source: Based on data from Toronto Transit Commission, 2016.

Toronto’s efforts show the potential for simple measures to make a large difference in growing ridership for public transit, thereby achieving better environmental results – but was instituted at a time when buses were predominantly diesel or hybrid. We now know that it is also possible for the buses themselves to be a much bigger part of the climate solution.

Clean the Air

Air pollution is a serious global health issue. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there are 4.2 million premature deaths every year from outdoor air pollution. And most of us are exposed: more than 90 per cent of the world’s population lives in areas where the air quality fails to meet WHO standards.

Historically, most buses are powered with diesel, a particularly dirty fuel. Diesel vehicles are a major contributor to bad air quality. These engines emit fine particulate matter, smog-forming compounds, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and other toxic substances. Diesel exhaust can deposit soot deep in our lungs, irritate our respiratory systems, weaken our immune systems, and some exhaust compounds have been linked to cancer. Fetuses, young children, and those with chronic illnesses are particularly vulnerable.

Electric buses produce none of these tailpipe emissions. Even when the electricity used to power electric buses is generated from coal, the buses typically are responsible for producing fewer greenhouse gas emissions and less pollution than diesel buses: power plants are built with pollution-control measures not found on buses.

For almost every city, the pathway to zero-carbon public transportation involves electric buses. Electric buses can be added to the city’s public transportation system quickly and easily, because other than charging infrastructure, which can be concentrated in centralized facilities, they require no additional land, construction, or municipal redevelopment. And when the electricity used to power the buses is zero carbon, so too are the buses. But until very recently, electric buses were seen as only possible in the future. Today, except for cities in difficult climates where battery performance is still being assessed, electric buses are here, are reliable, and have been proven in enough cities that a rapid transition can happen now.

In most cities, barriers to adoption of clean electric buses are not technical but financial – even though the lifetime cost is lower, they are more expensive to buy, and that creates an obstacle in many places. Although electric buses are currently more expensive to buy than their diesel counterparts they have lower operating costs: today, in a busy transit system, they have a lower lifetime cost than diesel (due to the lower maintenance costs), and they are projected by Bloomberg New Energy Finance to have purchase price parity with diesels by 2030.

Numerous cities have made a strong commitment to electric buses. They have demonstrated that the real obstacle to dramatically reducing emissions from the world’s bus fleets is inertia.

Better, Cleaner Buses: From China to the World

China is often thought to be a climate laggard but is actually a leader in electric transportation. Shenzhen, a city of nearly thirteen million permanent residents, has nine hundred bus lines, and more than sixteen thousand buses, all of which are electric (Figure 5.2). It has the world’s first 100 per cent electric bus fleet, which it created in little more than six years (starting in 2011).

Figure 5.2: Electric Bus Adoption in Shenzhen, China, 2012–2017

Shenzhen implemented an entirely electric bus fleet in an extraordinarily short time. Source: Based on data from Shenzhen Urban Transport Planning and Design Institute Co. Ltd.

Conversion to a fully electric fleet of buses reduced Shenzhen’s greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 1.35 million tons per year. Even though the electricity that powers these buses is largely generated from fossil fuels, the power plants have stronger pollution control measures than those available for diesel vehicles.

The buses are capable of traveling an average of 250 kilometers (about 155 miles) on a charge. A full recharge takes five hours, so most bus routes have charging facilities. The city currently operates one charging outlet for every three electric buses, and some of these stations double as charge points for private cars and taxis.

The city government also is driving electric bus adoption as an economic development strategy. BYD (which stands for “Build Your Dreams”), a global leader in manufacturing electric buses, supplied nearly all of Shenzhen’s buses and is headquartered there, employing forty thousand people.

As of 2017, 99 per cent of the world’s 385,000 electric buses could be found in China, partly because of important subsidies provided by the national government that lowered the cost of acquisition and provided a direct stimulus to the emerging manufacturing industry. Until 2016, more than half the costs of a new electric bus were covered by these subsidies, making them the most cost-effective option for Chinese cities. Now that the cost of new buses is rapidly dropping as a result of advances in manufacturing and the growth of the industry, the Chinese government is phasing out the subsidies, which will disappear completely by 2021. The program demonstrates how smart policies can drive positive change, make cities better places to live – and create jobs.

Electric Bus Adoption Can Spread Rapidly

It isn’t essential, however, to have the support of a powerful centralized government to convert a fleet to electric buses. Santiago, Chile, has also made wonderful progress on its electric bus rollout – and it has done so without major federal subsidies.

Santiago is located in a valley between two mountain ranges. As a consequence, pollution becomes trapped in the valley, particularly in the winter months when the cold air pools in low-lying areas, allowing pollution levels to build up. This has health and economic consequences for the city: four thousand premature deaths per year are attributed to air pollution, and the annual health care costs of this problem amount to more than US$500 million – recent figures suggest as much as US$670 million.

In the winter months, it is not uncommon for the city to declare environmental emergencies due to harmful concentrations of smog. On these days, polluting industries are forced to shut down their operations, a significant percentage of cars are banned from city roads (based on license plate numbers), the use of home woodstoves is prohibited, and people are encouraged to stay indoors. This has economic and social repercussions that have caused citizens to demand that government address air quality. As expected, the course of action that reduces air pollution also reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2012, 79 per cent of Santiago’s greenhouse gas emissions came from transportation, while 38 per cent of all trips in the city were made using public transportation. The city needed a way to reduce the pollution and emissions generated from their public transit to help mitigate the air-quality challenges. Electric buses were an important part of the solution.

In 2017, Santiago took an important step toward electrifying its bus fleet by starting a pilot program with two electric buses leased from the local affiliate of BYD – Enel-BYD. It added a further 200 electric buses between December 2018 and the end of January 2019, and in October of 2019, it took possession of 180 more, well on its way to achieving its goal of converting 25 per cent of its roughly 6,600 buses to electric by 2025. And by 2040, Santiago aims to have an all-electric fleet.

It is important to understand how remarkable it is to add nearly four hundred electric buses in less than a year. Fleet purchases – buses, garbage trucks, postal delivery vans – are planned out over many years, sometimes decades. Changing purchasing plans quickly requires decisive leadership. Other cities are studying electric buses, some are piloting, many are debating the costs and merits. Santiago committed to electric buses. Today, Santiago has the biggest electric bus fleet in Latin America and one of the biggest fleets globally. Its leadership demonstrates that in South America, it is practical and feasible to make a rapid transition from diesel to electric transportation – an important step in addressing the significant portion of urban greenhouse gas emissions caused by transportation.

The buses that Santiago chose, like those in Shenzhen, are capable of traveling 250 kilometers (155 miles) per charge. This means that, despite steep roads and heavy ridership, these buses are capable of completing their entire daily route on a single charge with recharging occurring at night. Two depots at opposite ends of the city have been upgraded to accommodate charging for the buses, and at the time of writing this book, three new charging depots were under construction.

Those charging depots have double duty. Solar panels covering the parking areas provide some of the energy used to power these buses. Some buses are served by a contract that ensures the power used for their charging is sourced from 100 per cent certified renewable energy.

Santiago is one of the cities that is taking advantage of innovative financing options for its electric buses. A “turnkey” lease model is used here. Two energy service companies (Engie and Enel X) supply all the services required to operate electric buses in the city: the buses, the charging infrastructure, the maintenance services, and the energy used to power the buses. This lease agreement is part of an overall partnership between the manufacturer of the buses, the energy service companies, the municipal bus operators, and the Chilean government.

According to media reports, transit riders are enthusiastic about the electric buses. The buses are new, cleaner, quiet and have a smoother ride, and also come with perks. These include air conditioning, free Wi-Fi, USB chargers – and no smell of diesel. Rather than arrive at work stressed from traffic, Santiago’s electric bus riders can relax, play games, or even work as they travel to their destination.

Santiago has also adopted city-planning measures to complement the use of public transit through active transportation. To help transit users get to their destinations faster and easier, the city has introduced bus-only lanes and bus-signal priority. The city center was redesigned to give priority to active- and public-transportation users, including adding cycling infrastructure, a bikeshare program with 2,600 bikes, a free bicycle taxi in the city center, and cycling education in primary schools.

Electric buses are viable in European and North American contexts as well. Milan, which is a city where electrified transit has a long history, has demonstrated what is possible.

Building on History in Italy

Milan is a modern, business city – but a city with roots going back to the fourth century BCE. Its tram system was introduced in 1876 and still forms a critical part of the public transportation system today. Although the first trams were pulled by horses, the system was fully electrified by 1901 and remains electric to this day. Some of the earliest trams, introduced to the city between 1928 and 1930, are still in operation. (These iconic trains are similar to those that operated in a number of North American cities such as San Francisco and are an early example of how transformative ideas can spread rapidly from city to city.) In total, Milan currently has nineteen tram lines with 175 kilometers (about 109 miles) of tracks. Like a spider’s web, most of these tracks radiate out from the city center, connecting the suburbs to the downtown.

Milan also has a network of trolley buses. These electric buses source their energy from overhead lines like trams, but unlike trams, they do not require tracks embedded in the road. Trolley buses were introduced in 1933 and remain a vital part of Milan’s public transportation network, primarily moving passengers around Milan’s outer ring road. The latest versions are equipped with batteries that allow the buses to travel up to fifteen kilometers (about nine miles) off the overhead network, which gives the buses the ability to detour around construction, accidents, and other road obstacles.

Milan also has four extensive subway lines extending one hundred kilometers (about 62 miles), and a fifth is under construction.

The last component of Milan’s public transportation system is its buses. Its 1,502 buses are nearly all diesel powered, and they are the major target for electrification. By 2030, Milan plans to convert its entire bus fleet to electric; at that point, it will be the first major European city to have a fully electric transportation system: trams, trolleys, subways, and buses.

Milan is building the infrastructure needed to support a fully electric bus fleet. Four new bus depots with automated recharging are planned, with the first to be completed in 2021. In addition, three bus depots are being restructured to accommodate the needs of electric buses. On-route charging will also be available at terminuses across the city.

As it waits for the charging infrastructure to be built, Milan is replacing its oldest buses with hybrid electric buses. These buses have an electric motor that is recharged through regenerative braking and an internal combustion engine, and they emit up to 30 per cent less carbon dioxide pollution than their full-diesel counterparts. Some models are designed to use the electric motor exclusively when stopping and starting to reduce the air pollution levels around the bus stops where people congregate.

The electricity that powers the trams, the trolley buses, the subway trains, and soon the buses is 100 per cent renewable. Once the last diesel bus is gone in 2030, Milan will have a zero-emissions public transportation system. Promotion of the use of public transportation is therefore a critical strategy for the success of its climate-action plan. Located near the car-manufacturing centers of Italy, Milan has one of the highest rates of personal-vehicle ownership in Europe. However, ridership of the public transportation system is also high. More than two million trips per day are taken on the system within a metropolitan area with slightly more than eight million inhabitants.

To help provide alternatives to personal vehicle use, Milan offers additional services. Many of its bus routes operate all night, and in some districts, an on-demand “radio bus” is available to get you to your final destination late at night. Parking is available near transit routes, and there is a bikeshare program connected to transit that includes e-bikes and even child seats.

The Final Word

Zero-emission public transportation is possible today. Many cities have excellent subway systems, light rail, or streetcars. Those need to be expanded both for transportation reasons and so the city can grow in a dense and sustainable way. At the same time, decarbonizing a significant part of the public transportation system is possible – in the very short term – by transitioning rapidly to quiet, clean, electric buses.

While China has made the most progress, it’s clear from other global cities that electric buses are viable now and result in significant improvements to air quality, noise, and carbon emissions. Smart governments are using the right public transport policy to create jobs and new industries supplying those buses. Santiago shows that this model works in South America, and Milan demonstrates how a multi-modal public transportation system can also become zero carbon in Europe. Addis Ababa, a city in a developing country in Africa, is moving toward zero-emission public transportation. It is clear from these examples that there are no technical impediments to the mass adoption of electric public transport – only inertia and a lack of political will. Zero-emission public transportation protects our climate and our health, keeps our cities clean, helps us move around, and increases the mobility of our most vulnerable. Like most good climate policy, it’s a win for all.