THE STALIN CULT burst upon the public scene with a big bang late in 1929 and was followed by three and a half years of near silence. On 21 December 1929 Stalin turned fifty years old. The eight pages of Pravda on that date were filled with laudatory articles by fellow Party bosses extolling Stalin’s role in the history of the Party as well as his various functions of general secretary, mastermind of the Soviet industrialization drive, organizer of the USSR, and theoretician of Leninism; congratulatory telegrams by the Communist Party leaderships from Italy to Indonesia and by factory committees and trade unions from all over the Soviet Union; and photographs, with a photo portrait adorning the front page (Fig. 2.1).1 Other newspapers followed suit and featured similar greetings and visual representations, suggesting that the beginning of the Stalin cult was orchestrated and centralized.2 This glorifying salvo in multiple papers must have seemed startling to readers, for throughout the 1920s, Stalin in public representations had paled in comparison to other high-ranking Bolsheviks such as Lenin, Trotsky, and Kalinin. Because Stalin controlled the media since at least 1927, there can be no doubt that he acquiesced to this gambit of minimizing his cult.3

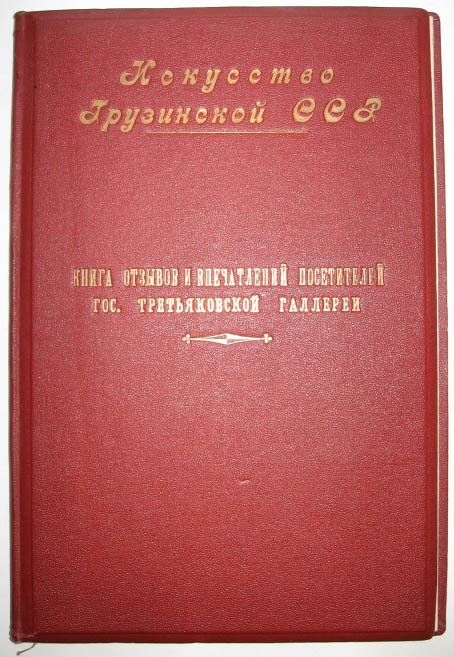

This chapter charts Stalin’s image in Pravda from the beginning of the cult in December 1929 until early 1954, a year after his death. It provides a sense of continuity and change in the depiction of Stalin. Its focus is on visual representations—mostly photographs—but it includes some verbal ones as well. It is based on a reading of every page (amounting to a total of about forty thousand) of the newspaper, which for most of the period was six pages long.4 Visual representations of Stalin are broadly defined as, inter alia, photographs, reproductions of paintings, depictions on book covers, and portrayals in plays or movies. Statistics of these visual representations are in an appendix at the end of the book.5

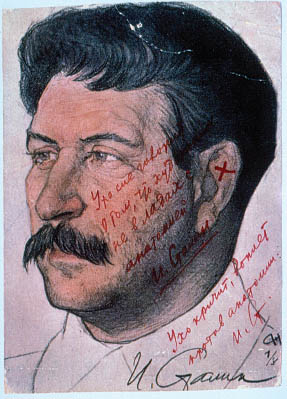

Figure 2.1. Stalin on his fiftieth birthday. Pravda, 2.1 December 1929, 1.

Why Pravda? Pravda was much more than the first socialist state’s premier newspaper: it was both a mirror of the Soviet political, social, and cultural landscape and an invaluable compass used to navigate through this rugged terrain. The Party official in a Karelian village read Pravda behind his desk at the kolkhoz soviet in order to stay in tune with the contorted Party line. The history teacher in Kazakhstan could not explain current affairs to her steppe nomad students without the most recent issue of the paper. The agitprop activist stationed with a Red Army unit in the Soviet Far East feared for his life if he overlooked Pravda’s exposé on an “enemy of the people”—the same highly decorated general whom he had just praised in front of his soldiers. Stalin’s place in the topography of Pravda was central. The painters discussed in this book all read Pravda to trace the zigzag Party line. “Don’t you read the papers?,” shouted “a voice in the audience” at the speaker during a Moscow Artists’ Union meeting in 1938.6 More importantly, the painters also read Pravda to get inspiration for a portrait from a new, usually photographic, visual representation of their leader (such as was soon to be distributed among them as a template in the upcoming Stalin portrait competition); to get inspiration from a new verbal source, as in an idea propounded in a Stalin quote; to get cues about shifts in art politics, as from a comment by the art critic Osip Beskin; or to survey their own status in the art world, shown by the number of their paintings that were reproduced in the premier newspaper (Figs. 2.2, 2.3, 2.4). Stalin’s portrayal in Pravda, then, was both a microcosm of the total of the Stalin cult and an influential medium of the Stalin cult. Photographs of Stalin—most of them first publicly circulated via Pravda—were, until the appearance of the first Stalin movie in 1937, the master medium of the Stalin cult insofar as they canonized his image. They provided the expressive language of his depiction, which was then followed by other media.

Pravda was founded in tsarist Russia in 1912 as a workers’ daily and remained one of the few operating newspapers after the Bolsheviks closed down private and heterodox socialist papers following the October Revolution. In early Soviet Russia, both Pravda, the Party organ, and Izvestia, the newspaper representing the state, were considered elite. Both were read mostly by Party activists of intelligentsia background. In the early 1920s, the Bolsheviks founded mass-circulation newspapers targeted at specific audiences—for example, Krestian-skaia gazeta at the peasants, Rabocbaia gazeta at the workers, Rabocbaia Moskva at Moscow workers, and Bednota at rural activists and officials. Most of these papers were discontinued in the second half of the 1930s, since literacy had increased as a result of the Soviet leap into industrial modernity during the Great Break (1928–1932), and the principle of targeting such specific audiences had been abandoned. Consequently, Pravda increased in stature, circulation, and reach.7

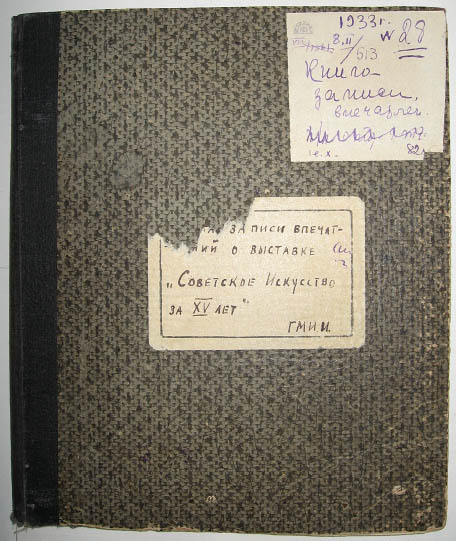

Figure 2.2. Photographs like this one indicated to the Stalin painters who, and which style, was fashionable. The caption says: “At the exhibition ‘Artists of the RSFSR over the Past Fifteen Years’: left: the Lenin room, right: the Stalin room.” Pravda, 2.8 June 1933, 4.

Figure 2.3. “At the Lomonosov State Porcelain Factory (Leningrad) the artist A. A. Skvortsov finishes painting a vase with a portrait of Comrade Stalin (from a painting by artist Brodsky).” Pravda, 19 April 1935, 4.

Figure 2.4. “A delegation of artists and sculptors after greeting the Congress of Soviets. The delegation presented the Congress with a portrait of Comrade Stalin by the artist A. Gerasimov and artist Konchalovsky’s painting Flower Bouquet.” Pravda, 6 February 1935, 4.

Pravda and a number of other newspapers were the main medium through which the original Stalin cult was launched on Stalin’s fiftieth birthday in December 1929. At that time the audience of Pravda had expanded to include the engineers and workers on the construction sites of the First Five-Year Plan and the kolkhoz accountants in the villages. The circulation was one million copies in early 1930.8 The Bolshevik leadership used Pravda to push certain themes, and other papers followed suit by producing articles on agenda points first set in the leading news outlet. Stalin effectively coopted Pravda much earlier, in 1924, when he entered into a coalition with the main editor, Nikolai Bukharin, during the struggle over the Party leadership after Lenin’s death.9 In the same year, the photographic depiction of Party leaders was centralized and placed under the control of the secret police.10 Stalin and Bukharin split in 1927, and the latter was ostracized as part of the “Right Opposition.” In consequence, Stalin staffed the editorial board of Pravda with supporters who continued to ensure his control.11 Stalin’s editorial control was largely informal and based on oral communication—the editor of Izvestia, Ivan Gronsky, recalled regular telephone conversations with Stalin in 1928–1929 during the final battle against the Right Opposition.12 Starting in 1930 with Lev Mekhlis, Stalin began appointing his own men as editors in chief of Pravda. At the time, few people were closer to Stalin than Mekhlis: he had been Stalin’s secretary and personal assistant, functions that on paper sounded routine but in fact were equivalent to ministerial posts in a shadow cabinet. Mekhlis was one of the few gateways to the dictator, and thus one of the most powerful men in the Soviet Union.13

After the ousting of Bukharin and the appointment of Mekhlis, the smoothly working control mechanism of Pravda (through Stalin and his secretariat) most likely operated as follows. All articles that remotely had to do with Stalin’s person were sent to his secretariat for approval. For instance, on 17 August 1938 Pravda editor Lev Rovinsky sent to Stalin’s head secretary, Poskryobyshev, galleys of an article that contained passages about a meeting with Stalin and accompanied this article with the following note: “For Aviation Day Comrade Kokkinaki wrote an article for Pravda. . . . Since there are references to meetings and conversations with Comrade Stalin, I am enclosing two copies of the article and ask you to authorize the publication of these parts of the article. The parts are marked in red pencil on one of the copies.”14 On 13 April 1939 the editor of Komsomol’skaia Pravda, a certain Poletaev, sent an article entitled “I Remember the Young Leader,” by G. Yelisabedashvili, to Poskryobyshev along with the following letter: “The editorial board of the newspaper Komsomol’skaia Pravda asks that you look through the memoir of Comrade Stalin’s youth which we plan to publish in the next issue of our newspaper. The material is verified and authorized (zavizirovan) by the Tbilisi branch of the IMEL [Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute] at the Party Central Committee.” Stalin wrote across the letter: “I am against the publication. Among other things, the author shamelessly told lies. J. Stalin.”15

Photographs were sanctioned in a very similar way. On 24 February 1934 the deputy editor of the Russian version of the journal USSR in Construction (SSSR na stroike) wrote to Stalin’s secretariat: “To Comrade Poskryobyshev. The editorial board sends you an unpublished portrait of Comrade Stalin (the photograph was shot at the seventeenth Party Congress) and asks that you give permission to publish it in the next issue of our journal. The photograph has yet to be retouched.” Poskryobyshev noted: “The photograph ought to be retouched and shown[.] Poskryobyshev. Likely there will be no objections against this photograph.”16 Sometimes Stalin—via his secretariat—was given a choice of which portrait to publish, as on 4 December 1943 when “major general, editor in chief N. Talensky” on behalf of the editorial board of Krasnaia Zvezda wrote to Poskryobyshev, “I ask for permission to publish in Krasnaia Zvezda in an issue devoted to the Day of the Constitution one of the herewith enclosed portraits of Comrade Stalin,” attaching two 1943 Boris Karpov drawings of Stalin, one without a hat, the second with a hat.17 And of course canonizing a photograph by publishing it for the first time was a more sensitive undertaking than republishing a previously approved photo: “Dear Comrade Poskryobyshev! I am attaching an offprint from a plate that we want to publish in the December issue of our journal. This photograph has never been published. I implore you to allow us to publish it.”18

There is evidence that Stalin looked at the photographs himself and actively took part in the decision to publish them or not. On 16 June 1935 Lev Mekhlis wrote in curt terms (implying close familiarity) to the man who presently filled the position in Stalin’s secretariat that he once held: “Comrade Poskryobyshev! The 17th marks the fifth anniversary of the opening of the Stalingrad tractor engine [factory]. I want to publish a photo of Ordzhonikidze and Stalin. Show it, please! (Pokazhi, pozhaluista!).” “Show it, please!” most likely meant: “show it to Stalin, please!” Across the note there is the handwritten phrase: “Not worth publishing (Ne stoit pomeshchat’).”19 An even clearer example is a note that Poskryobyshev received from someone on the editorial board of Izvestia on 17 June 1937: “Dear Comrade Poskryobyshev! I ask that you allow Izvestia to publish the enclosed photo in the 18th June issue, which is dedicated to Gorky.” Written across this note I found, “Comrade Stalin objects (t. Stalin protiv).”20 How regularized and permanent was this kind of direct control by Stalin and his secretariat? We cannot know. But we do know for sure that the dictator’s control over the country’s leading newspaper was one of intervention when he saw fit.

Only a diachronic analysis can shed light on the changes that took place in Stalin’s representation. At the beginning of the period studied, the first sign that Stalin’s birthday was approaching came on 18 December 1929 when a first batch of congratulatory anniversary telegrams was published on page three. A day later a second batch was published, again on the third page. On 20 December, Stalin’s representation had climbed up to page two, with a poem by Demian Bedny, while the rest of page two and page three again featured congratulatory telegrams. The Stalin presented in the 21 December birthday issue, finally, was an overwhelmingly verbal, not visual construct. There were three kinds of verbal contributions. First, there were multicolumn articles by his fellow Bolshevik luminaries, extolling his specific qualities (Ordzhonikidze’s article “A Staunch Bolshevik”), stressing a particular function of Stalin (Manuilsky’s article “Stalin as the Leader of the Comintern”), or highlighting stations in his revolutionary hagiography (the article “Tsaritsyn”). Second, there appeared short telegrams and congratulatory greetings from Communist organizations or other collectives from the Soviet Union (the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions or the “workers of the Tbilisi shoe factory”) and abroad (from the “Central Committee of the North American United States”). Third, there were article-length or poetic tributes by figures of the literary establishment (Demian Bedny’s poem “I am certain” [“Ia uveren”]). Generally all verbal representations kept distance and refrained from terms of endearment or excessive metaphoric or other figurative descriptions of Stalin. In the 117 greetings Stalin was designated as “leader” most frequently with the terms rukovoditel’, matter-of-factly signifying his function (76 of 201 times), and vozhd’, connoting more heroic, charismatic qualities (49 of 201 times). The most typical designations were “leader of the Party” (both rukovoditel’ and vozhd’).21 Later in the 1930s the charismatic and sacral vozhd’ (with linguistic roots going back to Old Church Slavonic) came first to surpass and then completely eclipse the newer and more sober term rukovoditel’.

If a Pravda reader on that December day had any inkling that the eight pages gave but a foretaste of a full-blown Stalin cult, the reader would have certainly thought that this phenomenon was going to be verbal, not visual. The quality of the pictures that did appear was poor, but this was a general technical problem with Pravda. On the front page there was a photographic portrait of Stalin’s face, occupying about one-sixteenth of the page, a fraction of the size of later front-page Stalin photographs (see Fig. 2.1). Stalin was shown fairly young, with jet black, full and quite unruly hair, not yet combed backward in the style he would later adopt. The photo must have been shot at least one year earlier, because Isaak Brodsky’s 1928 Stalin painting was clearly modeled on the same picture. Stalin gazed directly at the onlooker, not into the distance, as was typical of later images. The second page featured the later canonical January 21 photograph of Stalin and Lenin in Gorki, with Stalin sitting in the foreground in his white uniform. On page three, in connection with articles on Stalin and the Red Army, there was a small and poor-quality photograph of Stalin with Budyonny, walking in his characteristic army boots and riding pants. Pages four and five showcased even lower-quality photographs—of Stalin and Kalinin, with Stalin’s hand in his field jacket in Napoleonic fashion, and Stalin and Molotov respectively. Finally page seven had a tiny frontal photo portrait of Stalin, Lenin, and Kalinin.

After the birthday, throughout 1930, Stalin’s appearances were quite rare and limited to specific dates, such as Party congresses and holidays like the Day of the October Revolution. There was a strong sense of openness and indeterminacy. So much so that the headline of an article in early January 1930 could read “The Stalin faction (Stalinshchina) is fighting for leadership in the Donbass,” using the pejorative suffixshchina.11 At the beginning, the genre of visual representation too was less fixed, ranging from caricature-like drawings by Viktor Deni, to constructivist montaged photographs by Gustav Klutsis, to retouched photographs. And within these genres, there were surprises, as with an image in which Stalin suddenly seemed much older than in the other pictorial representations that had circulated so far. At this time, Stalin still appeared in advertisements, as in an ad for the printed version of his April 1929 speech, “On the Rightist Deviation in the VKP(b) (O Pravom uklone v VKP(b)).”23 Stalin quotes printed across the upper right corner of Pravda, the place reserved for the slogan of the day, or visualized as slogans on banners, became more common and occupied increasing space in the newspaper. So did the greetings, congratulations, and self-commitments to Stalin. To begin with, Stalin sometimes replied to these utterances, as in his own public congratulatory three-line greeting on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the Comrade Stalin Cavalry Brigade: “A heartfelt greeting to the Special Cavalry Brigade on its tenth anniversary. I hope it remains a model for our heroic cavalry units. J. Stalin.”24

But again, 21 December 1929 was not the beginning of a continuous process of showcasing Stalin. It was followed by silence. Between 1930 and mid-1933, Stalin made only rare appearances on the pages of Pravda. When he did, he was shown together with other Party functionaries and was not marked as outstanding or seen on socialist holiday occasions. This hiatus has been attributed either to a deliberate attempt to avoid linking the person of Stalin with the upheavals of collectivization, or to vestiges of opposition to his single power in the Party. Not surprisingly, there were no greetings from kolkhoz farmers on 21 December 1929.25 Whatever the case, in mid-1933 the public Stalin cult took off in multiple media.

Of course Stalin’s personality cult—even when on hold from 1930 to mid-1933—was accompanied by a new emphasis on “the individual” or “personality” (lichnost’), as evidenced in such phenomena as the beginning star system of movie actors (in contrast to Eisenstein’s and Vertov’s anonymous actors); the cults of other Party magnates, as with the Pravda celebration of Voroshilov’s fiftieth birthday on 5 February 1931; and the cults of the heroes of the First Five-Year Plan, for example in a full-page Pravda article featuring images of some of them (accompanied by short summaries of their achievements) and adding, “The country ought to know its heroes. The outstanding shock worker, the inventor, the rationalizer (ratsionalizator) who has mastered production technology—this is the hero of the land of socialism under construction.”26

With the take-off of the Stalin cult in mid-1933, the genres of representation also became more fixed. Deni caricatures and photomontages gave way to (retouched) photographs, sculptures (in late 1934), and the first reproductions of socialist realist paintings, as with Mikhail Avilov’s picture The Arrival of Comrade Stalin at the First Cavalry in 1919, taken from the exhibition “Twenty-five Years of the Red Army,” or Aleksandr Gerasimov’s 1934 painting Comrade Stalin Gives His Report to the Seventeenth Party Congress on the Work of the Central Committee of the VKP(b), 1934.27 At the same time in verbal representations, words derived from or connected with Stalin’s name became more common, as in Kirov’s dictum, “For the success of the Second Five-Year Plan we must work Stalin-like (po-stalinski),”28 and as in an article on the Day of the Soviet Air Force about “steel birds and people of steel (stal’nye ptitsy i stal’nye liudi)” where “steel” (stal) derived from Joseph Dzhugashvili’s pseudonym “Stalin.”29 The letters “S-T-A-L-I-N” sometimes became an emblem of his cult. Airplanes flew in formation to spell them out (Fig. 2.24, p. 71); or they were embodied by people, as in a 1933 Physical Culture parade at which the athletes formed up to spell the words “Hello Stalin (Privet Stalin)” when viewed from above.30 Verbal representations, however, during the take-off period of the Stalin cult (after mid-1933) were often still quite literal, as, for instance, in Beria’s 1934 article, “We Owe Our Successes to Comrade Stalin.”31

From the moment of the Stalin cult’s take-off in mid-1933 until the late 1930s Pravda was busy marking Stalin as the supreme leader, ultimately furnishing a canon of stock images or obrazy. First of all and most obvious, marking Stalin involved showing him alone and suppressing representations of other leaders. Just as it became clear in real politics around this time that Stalin could monopolize power if he wished, the newspaper drove home the point that Stalin could monopolize leader representations if he wished. To give an example, different articles in August and November on collectivization were accompanied by the same photograph of the Lenin’s Way collective farm’s “meeting of the individual peasant-farmers (edinolichniki) regarding their entry into the kolkhoz,” as the caption announced. But in August 1930 the wall in the background showed portraits of both Kalinin and Stalin, whereas by November only the Stalin portrait remained.32 The formation of a canon also involved distinguishing Stalin from other Party leaders in pictorial representations of groups, say in a photograph of a presidium on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater. Such strategies of visual distinction revolved around Stalin’s size, his place in the picture, the color of his clothing, his arm movements, and the fact that his hands never touched his face whereas others rested their heads on their arms or held earphones to their ears. For example, in photographs of the presidium of a Party meeting, Stalin was often placed in the center.33 What is more, in photographs of the Seventeenth Party Congress of February 1934, Stalin was the only Party leader with a light-colored uniform, thus standing out from his comrades Molotov, Ordzhonikidze, Kirov, et al.34 A picture of Stalin and his Party cronies with the leader of the epic Arctic expedition of the ship Chelyuskin, Otto Shmidt, likewise illustrates the point (Fig. 2.5). The coloring of his uniform was likely achieved by retouching, or even by gluing an entire picture of him into an existing photograph, because his appearance was very unnatural in these pictures. At other times Stalin’s dark clothing set him apart from the light clothing of others.35 Furthermore Stalin was sometimes the only top Party member with his arm raised higher than that of others, say, in greetings to a Physical Culture parade marching across Red Square.36 Or, in a February 1934 photograph of Kaganovich giving a speech in the presidium of the Seventeenth Party Congress, “The Congress of Victors,” Ordzhonikidze, Voroshilov, and Molotov rested their heads on their hands, while Stalin was the sole Party boss whose hands did not touch his face.37

The direction of Stalin’s gaze was another sign of distinction. While others looked at each other, at their leader Stalin, at an object, or at the viewer, Stalin’s own gaze was directed at a point outside the picture. This visual strategy was time-tested.38 In Soviet Russia it acquired a new ideological-temporal dimension and came to signify the leader’s embodiment of the utopian timeline, with the leader gazing into utopia—the future of socialism or communism. In depictions of the young Stalin, the gaze was mostly pointed directly at the camera, not outside the picture: thus in a 1915 picture showing him with fellow revolutionary Suren Spandarian in their Turukhansk exile, Stalin gazes directly into the camera.39 Apparently it was only the crucible of the Revolution and the inheritance of the Party leadership from Lenin in 1924 that turned Stalin into the embodiment of materialist history, of the force that could propel humanity to utopia.

Stalin’s distinction was further marked by his portrayal as motionless, whereas the bodies of others were shown in a state of movement. Motionlessness in general became one of the key themes in representations of Stalin, and the word “calm” (spokoinyi) proliferated in reference to him. Objects of everyday life in Stalin’s immediate proximity—the pipe in his hand, a map, a newspaper or book—also set him apart from others. His closeness in the picture to the figure of Lenin or an image of Lenin—a poster or painting on the wall—was another distinguishing marker.

Moving outside the intrinsic features of the picture itself, the text accompanying pictures also marked Stalin as special. In the captions below group pictures Stalin was often mentioned first, no matter where he stood in the picture (Fig. 2.5).40 To further underscore his prominence, his name was often capitalized while the names of others were not. Later in the 1930s, however, Pravda turned to enumerating all those standing in the picture by position and refrained from giving Stalin’s name in capital letters.41 The placement of his picture also played a role. For a long time, it was never placed at the foot of a page. The page itself was divided into different zones with different levels of prominence. The upper-left quarter of the page right beneath the masthead was especially sacred: here decrees and the most important announcements were often printed.

Figure 2.5. Distinguishing Stalin from others by his place in the picture and color of clothing. In addition, the caption lists Stalin first. Pravda, 6 June 1934, 1.

Raising Stalin’s profile involved not only images but also words. In late 1932 and early 1933, a new monumentalism of published Stalin articles—now on the front page and sometimes taking up all of it—predated the take-off of the visual Stalin cult in Pravda.42 Yet at this early point Stalin’s legitimacy was still identified as derived from Lenin and his leadership of the Party.43 Later Pravda turned to citing the size of print runs and the number of translations into foreign languages of his writings as an indicator of Stalin’s greatness.44

These were the main visual and verbal strategies of making Stalin stand out that were used from mid-1933 to the late 1930s. Then how did his depiction change over time? Starting in 1934 Stalin began appearing in connection with the expeditions and flights of Arctic explorers and aviators, all of whom were presented as heroes and embodiments of the Soviet new man.45 Famously, Otto Shmidt and his fellow sailors from the ship Chelyuskin arrived at the Belorussian train station in Moscow and were later greeted by Stalin personally.46 Even more famously, two years later the aviator Valery Chkalov flew to the Soviet Far East in record time. Moscow greeted Chkalov and his crew with a ticker tape parade reminiscent of the welcome for Charles Lindbergh upon his return to New York from the first cross-Atlantic flight in 1927. Stalin personally greeted Chkalov and the second pilot in the crew, Georgy Baidukov, with a fatherly kiss; and a Pravda article read, “It was Stalin who raised these brave men.”47 The same year Stalin appeared with a new hero, Viktor Levchenko, one of the pilots who had flown from Los Angeles to Moscow.48 Perhaps most famously of all, Ivan Papanin and his crew of Arctic explorers purportedly gathered at the North Pole around a radio receiver to listen to their leader’s address. An article, “Warmed by Stalin-like Care,” read: “North Pole, 24 May, 7 P.M. (RADIO). Yesterday evening there was the extraordinary picture of a meeting of the thirty members of the leading unit of the expedition on the ice at the pole, listening to the reading of a telegram of greetings from the leaders of the Party and government. They gathered under the open sky, in a snowstorm, but felt no cold because the bright words and the anxious care of the great Stalin warmed them and they sensed the glowing breath of their beloved homeland.”49

These new hero cults were part of the Stalinist Second Five-Year Plan tradition of celebrating socialist heroes like the Stakhanovites, named after Aleksei Stakhanov who during a single six-hour shift in August 1935 allegedly surpassed his norm fourteen times by hewing 102 tons of coal. Invariably these hero cults were in dialogue with the Stalin cult and entailed what one might call sacral double-charge.50 The glorification of other outstanding personalities in conjunction with Stalin’s personality engendered greater sacral charge both for Stalin and the other celebrated person. Thus in 1936 the widow of just-deceased physiologist Ivan Pavlov in a Pravda “letter to Comrade Stalin” thanked the leader for all the attention her husband got during his lifetime.51

Generally speaking, as soon as it had become clear—by the mid-1930s—that Stalin was the supreme leader, the phenomenon of the personality cult began spreading to others, not only Party bosses in and outside Moscow, but also cultural figures. Alongside the Stalin cult in April 1935, for example, the cult of the Ukrainian national poet Taras Shevchenko appeared, a cult that was to serve as an example for many other writer cults, especially the vast cult of Pushkin on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of his death in 1937, a cult that was intricately tied with the Stalin cult with a Stalinized Pushkin reinforcing Stalin’s power and a Pushkinized Stalin reinforcing literature’s power.52 In pictorial representations this was true literally with Pushkin appearing in Stalin’s overcoat.53 Likewise on the occasion of the centenary of Gogol’s death in 1952, the sculptor Nikolai Tomsky produced a Stalinized Gogol bust.54

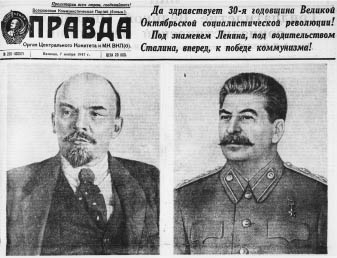

When Stalin and Lenin were shown together, Lenin was usually to the viewer’s left, Stalin to the right. In much of symbology, the left signifies beginning and the female, the right the end and maleness. It was unthinkable, for instance, that Stalin’s portrait be hung to the left of Lenin’s on the façade of the main department store GUM for a parade on Red Square; Lenin was always to the left of Stalin. In general the iconography of Lenin-Stalin seems to have been projected back onto Marx-Engels. The movement from left to right in depictions of the tetrad of Communist patriarchs, Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin, was to be perfected after the war. On the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the first publication of the Communist Manifesto (27 February 1948), a bas-relief showed all four heads looking to the right, with facial hair getting progressively shorter from Engels to Stalin (Fig. 2.6). Likewise on the occasion of the 125th birthday of Nikolai Ogarev, Pravda refracted the Herzen-Ogarev relationship through a Marx-Engels, Lenin-Stalin lens, pronouncing that “bourgeois historians of literature have depicted Nikolai Platonovich Ogarev, Herzen’s friend and comrade-in-arms, as ‘a pale companion to the bright star.’ In actuality Herzen was right, who said that he and Ogarev were ‘separated volumes of a single poem.’”55 As time went by, to be sure, the artistic genres of joint Lenin-Stalin depictions evolved. The bas-relief, showing white plaster Lenin and Stalin heads on a dark background in a usually round frame, appeared as a new genre of Stalin cult visual art as cult products turned more classicist.56 Interestingly, some of the other Party leaders were always shown with the same pictures. Molotov, for example, throughout the early 1930s was shown in a single image, sometimes rendered as a photograph, sometimes as a drawing.57

Figure 2.6. Left to right movement from Marx to Stalin. Pravda, 2,8 February 1948, 1.

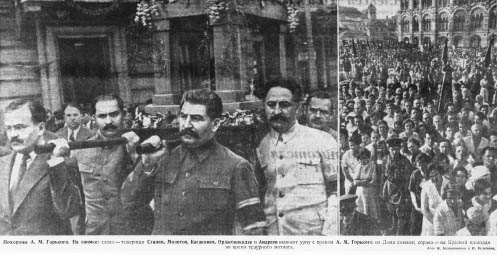

The popular Leningrad Party boss Sergei Kirov was murdered on 1 December 1934. A few days later Stalin appeared as a pallbearer at Kirov’s funeral, one of his many appearances as pallbearer, totaling fourteen (Fig. 2.7, 2.8).58 Did images like these establish an uncanny link between Stalin and (violent) death, as in the purges that followed the Kirov murder? Did this link stay in collective memory, ready to be reactivated during mass terror as in 1937? And did it thus counter the strategy of scaling back Stalin’s appearances in Pravda in times of trouble in order to avoid negative associations?

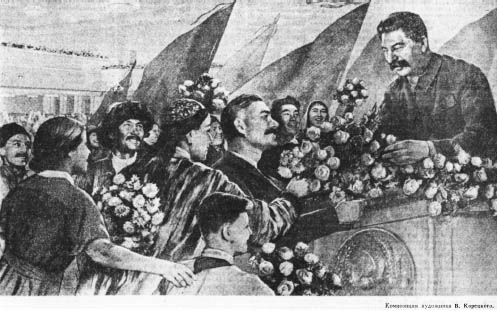

After the Kirov murder Pravda began a feature on Stalin’s involvement in the struggle for Tsaritsyn early in the Russian Civil War, further establishing this event as a key moment in the founding history of the Soviet Union, signifying the first defensive victory of the new country born in Red October. In early 1935 the first pictures of Stalin without a caption began appearing, testifying to a perception among the makers of Pravda that by now its readers were Stalin-literate enough to recognize their vozhd’ at first sight, without verbal explanations. At the same time reproductions of paintings became more numerous, larger in size, and more monumental in appearance, set in baroque gold frames when shown in the background.59 In the spring of 1935 representations of abundance and fertility burst upon the scene, symbolized by smiling Central Asians carrying exotic fruits or a newborn.60 There was also a sudden explosion of flowers, lakes, and nature, of nature metaphors as in a description of young athletes as a “blossoming generation” and an article by a young Pioneer, “I Gave a Bouquet to Stalin.” Such pastoral idylls pointed to the new sense of arrival, of nearing socialism, to an end of the emphasis on machines and heavy industry of the First Five-Year Plan, to an end of the hardships of building socialism.61 This was in conformity with the shift from machine to garden metaphors in socialist realist novels, as Katerina Clark has shown (Fig. 2.9, 2.10, 2.11).62

Figure 2.7. Stalin as pallbearer at Kirov’s funeral. Pravda, 7 December 1934, 1.

Figure 2.8. Stalin as pallbearer at Gorky’s funeral. Pravda, 21 June 1936, 1.

Smiles proliferated, and on the tribune of the Lenin Mausoleum even the Party leaders, including Stalin, smiled while applauding the parade on Red Square during the annual Day of the October Revolution.63 All this was encapsulated in the 1935 Stalin dictum, “Life has become more joyous, comrades, life has become easier!” Newspapers creatively adapted this formula, fashioning a binary opposition with life in the dark, capitalist West constituting the negative pole. Consider, for example, London correspondent N. Maiorsky’s headline, “Life Has Become Harder and Sadder.”64 1935, the year that had begun with the first wave of purges following the December 1934 Kirov murder, ended with the first picture of a New Year’s tree in Pravda.

Figure 2.9. Pravda’s only photo of Stalin with a biological child, Svetlana. Conforming to Stalin’s image of “father of peoples,” hereafter he was only shown with non-biological children. The image was credited to Nikolai Vlasik, Stalin’s bodyguard, tutor of his children, and majordomo after his wife Nadezhda Allilueva’s death in 1932. . Pravda, 3 August 1935, 3.

Figure 2.10. Stalin with Gelia Markizova, a Buriat Mongol girl. Pravda, 30 January 1936, 1.

Figure 2.11. Stalin with a blond boy at a Physical Culture parade at Moscow’s Dynamo stadium. Note the shift to ethnic Russian children. Pravda, 22 July 1946, 1.

Socialism arrived in the mid-1930s, officially first proclaimed with the Stalin Constitution of 1936. On a formal level, this change meant that horizontality triumphed over verticality. Beginning in 1930 Pravda had turned to statistics, graphically represented with steep upward curves, as well as photographs and drawings of the developing socialist cathedrals—blast furnaces, smokestacks, oil rigs, and electricity poles—likewise pointing upward. These were the representations of the building of socialism, of an acceleration on the utopian timeline. The mid-1930s marked the arrival at a plateau, an arrival that was expressed with horizontal representations, such as panoramic views of new socialist towns like Magnitogorsk, of gardens, or bird’s-eye-view maps.

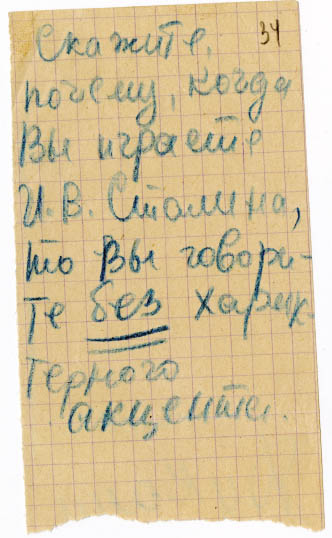

Similarly, in late 1935 the ethnic minorities of the Soviet Union began crowding the pages of Pravda. During the Moscow-based “week of national art” (dekada natsional’nogo iskusstva) of a specific minority, Stalin often made an appearance and was sometimes shown in appropriate national costume.65 How, then, was Stalin’s own ethnicity presented? The answer is surprising, but first warrants a look at the complex Soviet concept of ethnicity. The Soviet Union was not a nation-state but a federation composed of territories delimited according to ethnolinguistic criteria. Apart from citizenship of this federative Soviet Union, every Soviet citizen was ascribed a nationality, which matched (with some exceptions) one of the ethnoterritorial units. This nationality was recorded in such documents as the internal passport. Rogers Brubaker has described this bifurcated Soviet conception of ethnicity, which was to a large extent formulated by and under Stalin, with the terms “ethnoterritorial federalism” and “personal nationality.”66 Stalin was from Georgia, his personal nationality was Georgian, and in real life he bore many markers of Georgianness, starting with his thick Georgian accent and ending with his habit of appointing a toastmaster (in Georgian, tamada) at his late-night drinking banquets with his cronies in the Kremlin. At a dinner in his close circle after the 1937 Day of the October Revolution parade, with tongue in cheek he even told the Bulgarian head of the Comintern, “Comrade Dimitrov, I apologize for interrupting you, but I am no European, I am a Russified Georgian-Asian (obrusevshii gruzinaziat).”67 Yet Stalin was never depicted as a Georgian. As a critique of a draft copy of a heavily illustrated album of Lenin and Stalin put it, “The majority of the pictures . . . belongs to artists from Georgia. This creates the impression of Stalin as the leader only of the Georgian people, not of all peoples of the Soviet Union. This political flaw must be eliminated.”68 As “father of peoples” (otets narodov), one of his central images, Stalin, to use Brubaker’s terms, represented the “ethnoterritorial federation” of the Soviet Union, not his Georgian “personal nationality.” His representations were supranational and consisted of an amalgam of Bolshevik Party culture, Civil War traditions, and other sources. If Georgia (or any other personal nationality) appeared in his official depictions at all, then at most as a kind of wallpaper during the Georgian dekada, which started on 19 March 1936, that is, as folkloric background.69 Personal nationality did appear as a vestige of the representational techniques of a specific artistic culture, meaning that Stalin in a portrait produced by an Uzbek artist often looked slightly Uzbek with “Asiatic,” “slanted” eyes. Likewise, after 1945 and the enlargement of the Soviet space through the annexation of Eastern European countries, Stalin portrayed in a portrait by a Romanian artist appeared slightly “Romanian.”70 Later, during the rise of “Soviet patriotism” (considered by many a barely disguised version of Russian nationalism) at the end of the 1930s, especially during the war, Stalin’s image was Russified. For example, the main film actor starring as Stalin changed. Previously Stalin had been portrayed mostly by Mikhail Gelovani, a fellow Georgian with a heavy Georgian accent and a physical appearance startlingly like Stalin’s. Beginning with the 1948 movie The Third Blow, a new Stalin actor was introduced, Aleksei Diky, an ethnic Russian without an accent. Nonetheless, the Russification of Stalin’s image only went to a certain point. In fact, it mirrored precisely the proportion of Russian space compared to the many other ethnoterritories in the sum of the federative Soviet Union. But an excursus on Stalin and ethnicity would be incomplete without mentioning the potential danger posed by less official representations of his Georgian personal nationality. Suffice it to say that there is a long series of identifications of Stalin as Eastern, Asiatic “Other”—including such high points as Stalin’s “broad Ossetian’s chest” (shirokaia grud’ osetina) in Osip Mandelstam’s 1933 epigram and Karl Wittfogel’s 1957 study Oriental Despotism.71

As far as genres of Stalin representations were concerned, in early 1936 there was a marked move away from photomontages toward reproductions of socialist realist paintings. On 12 June 1936 a draft of the constitution that one month later became known as the Stalin Constitution was published in Pravda. It engendered a new performance of quasi-democracy, with citizens discussing the constitution and sending to Pravda letters addressed to Stalin.72 Soon thereafter Pravda served as a platform for initiatives to open Stalin museums.73 In early August 1936, the theme of Stalin in danger was developed in preparation for the first Moscow show trial of Kamenev and Zinoviev. Articles with titles like “Take Care of and Guard Comrade Stalin” and “Take Care of Your Leaders Like a Military Banner” were launched.74 Generally in Pravda the increase in violence in politics during the show trial was accompanied by an increase in love and tenderness for Stalin.

Early 1937 indeed showed a precipitous drop in Stalin pictures, likely to avoid linking him with the purges. During 1937 the flowers, gardens, fruits, and smiling Central Asians disappeared, together with the pictorialized Stalin. If smiles made a comeback at all during the year of the Great Terror, it was on the faces of ethnic Russian blonde Komsomol members and schoolchildren, in connection with the beginning of the new school year and Komsomol Day during the fall.75 The year 1937, one of the bloodiest years in Soviet history, drew to a close with an article on 30 December entitled “We Owe Our Happiness to Comrade Stalin.”76

Between January and May 1938 there again was much less Stalin representation than usual in Pravda, confirming the thesis that Stalin’s cult diminished during cataclysms like the Terror. Again, possibly to avoid negative associations, Stalin was kept out of the pictorial representations of the Soviet-German Nonaggression Pact.77 In the fall of 1938 the Terror was stopped, and the cult picked up again. Letters to Stalin by meetings of scientists, Party units, a congress of Soviet surgeons, the Third Congress of Leading Livestock Breeders of Kazakhstan, trade unions, and kolkhozes also came back with a vengeance. The first still pictures from movies with actors playing the role of Stalin began appearing in Pravda (Fig. 2.12).78 At the dawn of the 1940s the representation of Stalin’s age was conflicting. In some pictures he was shown as old, in others as young. In the course of three weeks in 1941 Stalin appeared first as aged with graying hair, then again as young, with his “Georgian” haircut, “Georgian” moustache (the ends pointed downward), and with hardly a single gray hair.79 This was a period of flux in which Stalin changed to a new paradigm—the image of the postwar generalissimo with deep wrinkles, an aging chin, graying hair, a Russian haircut, and a Wilhelmine moustache (with upward-pointing ends like Kaiser Wilhelm II).

The year 1939 ended with the greatest manifestation so far of the cult in Pravda, and any other medium for that matter—Stalin’s sixtieth birthday celebration (Fig. 2.13). For all high Soviet Party functionaries only round-number birthdays were celebrated in public;80 in fact, for Stalin there were normative documents expressly restricting birthday celebrations to these. The normative documents were a reaction to attempts to celebrate his fifty-fifth birthday.81 In this respect the Soviet festive cycle differed from that of Hitler’s Germany, where 20 April was always the holiday of Führers Geburtstag.

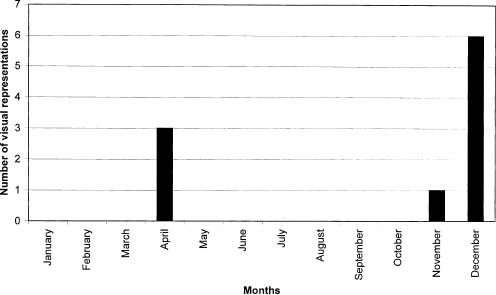

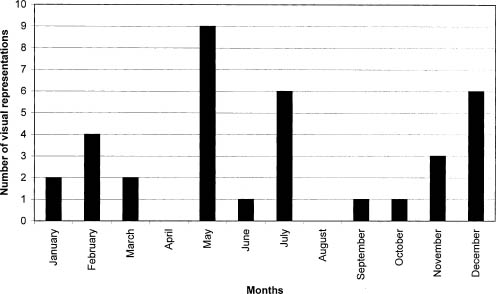

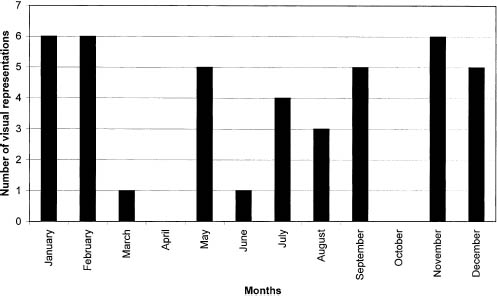

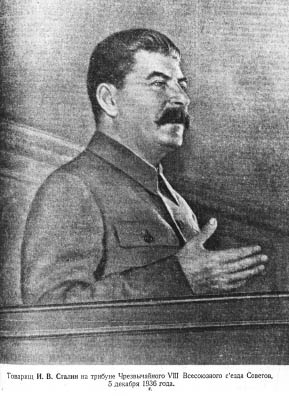

Pravda’s 21 December 1939 issue numbered twelve pages (in contrast to the regular six pages and the expanded eight pages of the 21 December 1929 issue), which itself is an indicator of the gigantism of the birthday celebrations. The number of visual representations during the birthday month of December overshadowed any other month (see Graphs 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3). A photograph of Stalin sitting at his desk with a pencil in his hand and several sheets of paper in front of him took up at least one-third of the front-page; let us recall here that in 1929 the photograph in the birthday issue occupied no more than one sixteenth of the front-page. Stalin was shown smiling benevolently, his hair neatly combed back, and his gaze directed to the right at a point outside the picture, not at the onlooker as in 1929. The long and anonymous lead article is entitled “Dear Stalin (Rodnoi Stalin),” carrying the kinship connotation that goes along with rodnoi. The upper right part of the front-page held a decree by the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet that bestowed upon Stalin the order of Hero of Socialist Labor. Below this decree there is an article signed by the Party Central Committee, “To the Great Continuer of Lenin’s Task—Comrade Stalin.”

Figure 2.12. The first still picture from movies with actors playing the role of Stalin: Mikhail Gelovani as Stalin in Man with a Rifle (1938). Pravda, 3 October 1938, 4.

Figure 2.13. Stalin’s sixtieth birthday. Note the emphasis on ethnic minorities, women, and children, who reinforce Stalin’s “father of peoples” image. Pravda, 22 December 1939, 1.

Compared with 1929, Pravda’s 1939 celebration of Stalin’s sixtieth birthday was a more visual event. Again compared with 1929, photographs were not greater in number but larger in size and better in quality. They accompanied texts and showed, for example, in the middle of a full-page article by Molotov on “Stalin as the Continuer of Lenin’s Task,” an image of Stalin with Molotov. Further articles were written by Voroshilov, Kaganovich, Mikoian, Kalinin, Andreev, Khrushchev, Beria, Malenkov, Shvernik, Shkiriatov, Poskryobyshev and Dvinsky, and Dimitrov. Typically the author would treat Stalin’s achievements in the sphere he represented, Voroshilov writing about “Stalin and the Buildup of the Red Army” and Dimitrov about “Stalin and the International Proletariat.” Compared with 1929, new topics included the agrarian sector, the title of Andreev’s article reading “Stalin and the Great Kolkhoz Movement,” and the nationalities issue, the title of Khrushchev’s article reading “Stalin and the Great Friendship of Peoples.” As in 1929, there was a small place reserved for “real news.” In 1929 this space was still half of the penultimate page seven, while in 1939 this area had been reduced to the rightmost, last slim column on page twelve. On 21 December 1949 news was completely effaced from the country’s main newspaper.

Graph 2.1. Visual Representations of Stalin in Pravda, 1929

Graph 2.2. Visual Representations of Stalin in Pravda, 1939

Graph 2.3. Visual Representations of Stalin in Pravda, 1949

For the entire month of January 1940, every issue of the newspaper carried a rubric on page two, three, or four entitled “Torrent of Greetings to Comrade Stalin in Connection with His Sixtieth Birthday,” with lists of individuals and organizations extending their congratulations to the leader. On 9 March 1940 and the surrounding days the newspaper celebrated Molotov’s fiftieth birthday, also with a rubric of congratulatory greetings, although under a different title (“From All Ends of the Country”), fewer in number, and shorter in duration. Of course in the representations of Molotov’s birthday, Stalin often appeared together with his close “comrade-in-arms.”

In February 1941 came the celebrations of Voroshilov’s sixtieth birthday, in which Stalin, as usual, played a huge role, amplifying Voroshilov’s status and his own.82 Everything changed on 22 June 1941, the day of the German attack on the Soviet Union. Smiles, which had been reappearing, even on Uzbeks and Tadzhiks at the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition in Moscow, were suddenly wiped off all faces. One day after the attack, on 23 June, Pravda featured a large photograph of Stalin occupying the entire upper right-hand quarter of the front-page. Stalin looked leftward, his nose very pointed, his moustache already faintly Wilhelmine. There were small crow’s feet in the corners around his eyes, but his hair had not yet turned gray. The slogan at the top of the page presented Stalin as the pivot of the Soviet Union, around whom all were supposed to rally: “Fascist Germany has rapaciously attacked the Soviet Union. Our heroic army and navy and brave falcons of the Soviet aviation will carry out a crushing blow against the aggressor. The government calls upon the citizens of the Soviet Union to close ranks even more tightly around our glorious Bolshevik Party, around the Soviet government, around our great leader—Comrade Stalin. Our cause is just. The enemy will be defeated. Victory will be ours.”83 The next day this point was driven home pictorially. A photo on the second page showed a large gathering at Moscow’s Stalin car factory with a Stalin bust in the center. Page four pictured a soldier holding the 23 June issue of Pravda with Stalin’s image in the “waiting room of the Oktiabrsky district draft center,” as the caption explained, and a Stalin bust in the background. Evidently to boost morale, in mid-December Pravda featured a still from a film of Stalin’s speech on Red Square on 7 November, the Day of the October Revolution. The caption identified Stalin as “Chairman of the State Defense Committee.” Typically, Stalin’s many Party, state, and military titles were deployed according to the situation. On 15 February 1942 there appeared a Stalin whose forehead now showed a deepening wrinkle.84 There was a new seriousness and decisiveness about him and his gaze into the distance now also signified his visionary premonition of the outcome of the war, of victory. As to clothing, the general’s cap with the Red Star appeared.85 In late March Pravda announced a new movie, The Defense of Tsaritsyn, whose story placed the old founding myth of Stalin’s defense of Tsaritsyn against domestic enemies during the Civil War in the new context of the Soviet Union against the foreign enemy during World War II. Interestingly, even though the film was set in 1919, the actor starring as Stalin—Gelovani—had changed his physical appearance to conform to Stalin’s emerging wartime and postwar image: his hair was graying, the moustache was Wilhelmine.86 Overall, however, there was a decline in visual representations of Stalin during the war. In fact the newspaper became more text based, with the exception of caricatures by the Kukryniksy, the artist trio Mikhail Kupriianov, Porfiry Krylov, and Nikolai Sokolov. Their drawings portrayed recent political events or protested against Hitler and the fascists, depicting them as cannibals, pigs, monkeys, and vultures.87 In Pravda, the visual image-based Stalin cult only really gained in profile near the end of the war, when victory was certain.

A heavily retouched photo showed a soldier single-handedly producing a self-made front newspaper called Fighting Newsletter (Boevoi listok), with a pencil in his hand filling the page right below the Stalin portrait he himself has supposedly just drawn—but such pictures remained an exception.88 The by now canonical representation of some of the major public holidays was suspended, and there was no picture of a May Day parade on Red Square. Instead on 1 May 1942 the front page featured a Stalin decree and a recent drawing of Stalin by Boris Karpov, executed with bold strokes and showing the leader as army commander with his general’s cap, in profile, looking left, with deep wrinkles on his forehead and around his eyes, and wearing a very Wilhelmine moustache. Instead of parade pictures on the following days, Pravda on 3 May showed a small photograph of a meeting of soldiers in the woods with several officers and a Stalin portrait on a makeshift tribune.89 Everything was now connected with the war. If a Stalin portrait at a worker meeting in a factory was shown, it was a defense industry factory. If a Stalin portrait at a concert was shown, it was a concert of the Red Army choir. If Stalin was shown with foreign dignitaries, they were generals or politicians of the Allied forces.90

In 1942, the Day of the October Revolution was another milestone on the road toward Stalin’s postwar pictorial representations. From now on he often appeared not in his customary army riding pants with high boots but rather in parade trousers, decorated with stripes on the side, and low parade shoes. The new image soon made its way into secondary representations, as in a painting in the background of a picture of the opening of a new Moscow metro line, where Stalin is shown in his generalissimo’s greatcoat and the new Supreme Commander in Chief’s cap. This image developed further: the gray started at his forehead and temples and later moved to the top of his hair, and spread to his moustache. Epaulettes and elaborate buttons appeared on his uniform. The pockets on the once simple gray military uniform were now stylized and pointed, and the collar became a high one.91 Bodily attributes of Soviet leaders turned into loaded signs and came to stand in for the whole person: think only of Stalin’s moustache, Khrushchev’s bald head, Brezhnev’s eyebrows, and Gorbachev’s birthmark. A turning point in the gradual move toward the postwar style of representations of Stalin as generalissimo came on 7 November 1943, when he was shown on the front page in a drawing by Pavel Vasiliev in his ornate military uniform. Stalin was looking right, his hair graying, his moustache Wilhelmine, much oakleaf decoration on his dark uniform. The caption read: “Decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet on the award to Marshal of the Soviet Union, Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin, of the Order of Suvorov.” Two pages further on, Stalin was shown speaking at Mossovet, the Moscow City Soviet, on 6 November, and here too his hair was gray.

Soviet Russia was not the only country where the bodily features of leaders became iconic signs. Italian writer Italo Calvino remembers from his youth the shift of depictions of Mussolini “from the frontal image to the side image, which was much exploited from that point on, in that it enhanced his perfectly spherical cranium (without which the great transformation of the dictator into a graphic object would not have been possible), the strength of his jaw (which was emphasized also in the three-quarters pose), the continuous line from the back of his head to his neck, and the over-all Romanness of the whole,” all prompted by the appearance in the early 1930s of a new equestrian monument at a stadium in Bologna. Mussolini’s physique infiltrated everyday behavior of the Italian population and inspired concrete practices. “In one of the affectionate games that people used to play at the time with children of one or two years,” Calvino recalls, “the adult would say, ‘Do Mussolini’s face,’ and the child would furrow his brow and stick out angry lips. In a word, Italians of my generation carried the portrait of Mussolini within themselves, even before they were of an age to recognize it on the walls. . . .”92 Mussolini’s protruding chin, his balding head, the often bare-chested torso, the clean-shaven face (vs. the moustached or bearded countenances of his Italian predecessors or his European rival statesmen)—none of these were neutral or insignificant. All of these corporeal features were powerfully signifying loci, and many of them had a latent antipode in Roosevelt, Hitler, or Stalin.

A new setting for photo opportunities also appeared in late 1942: increasingly Stalin was shown with foreign prime ministers and other high-ranking dignitaries in a dark wood-paneled Kremlin room, standing with his hands behind his back behind a table where either the dignitary or Molotov was signing a treaty, for example, that on “Friendship, Mutual Help, and Postwar Cooperation between the Soviet Union and the Czechoslovak Republic.”93 In these ceremonies a benevolent smile sometimes returned to Stalin’s face—after a near-total absence during the first years of the war. Also towards the end of the war, there appeared photos of Stalin at peace conferences meeting the other two members of the “Big Three,” first at Tehran in 1943, then at Yalta and Potsdam in 1945. S. Gurary’s famous Yalta photograph was published on Pravda’s front page on 13 February 1945 and depicted Churchill sitting on the left (seeming physically frail and disgruntled), Roosevelt in the middle, and Stalin on the right. Roosevelt was holding a cigarette (apparently retouched), Churchill was smoking a cigar, only Stalin was not smoking. He was smiling, dressed in his marshal’s greatcoat and general’s cap, and appeared to be the tallest of the three statesmen. In the spring of 1945, Pravda readers could get further visual cues that the end of the war was nearing. Stalin again reappeared in the background of photographs, as in a picture of the “management board of the Stalin artel, Ramensky district, Moscow region” shown “discussing the production plan of the kolkhoz for 1945.” Plans for the future, if only plans of a kolkhoz, were back, as were happy faces of the kolkhoz peasants.94

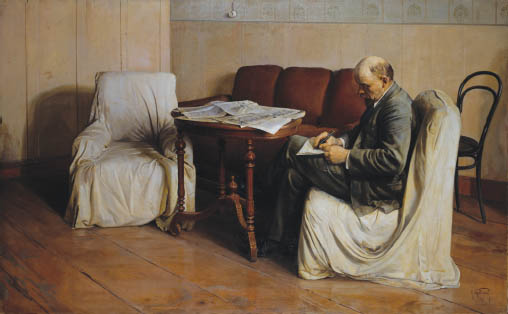

A majestic Stalin appeared in a 1945 picture by Boris Karpov on the front page of 1 May 1945, just a little over a week before the German capitulation (Fig. 2.14).95 This image shows Stalin in a dark marshal’s uniform with nine medals, his thumb between two buttons of his jacket in a semi-Napoleonic gesture, wearing long trousers and parade shoes, and with graying hair and moustache. In the background (presumably his office) behind him is a chimneylike contraption, and on the upper right-hand side of the wall is a canonical picture of Lenin reading a newspaper. The entire rest of the page was taken up by a Stalin text, a “decree of the Supreme Commander in Chief (Verkhovnyi Glavnokomanduiushchii)” to “give a twenty-gun salute” in the capitals of the union republics to honor the bravery of the Soviet nation on the war and home fronts and on the occasion of the May holiday. All the Stalin decrees appearing in Pravda towards the very end of the war either singled out specific generals, soldiers, or army units for praise or—symbolically—“ordered” them to do something, such as conquer Berlin. During the early phase of the war, there seems to have been a deliberate effort not to enmesh Stalin’s name with failures and defeats. At the victorious end, Pravda deliberately linked his name with the glorious deeds. On 2 May 1945, after a three-year gap (1942–1944) and for the first time since the beginning of the war, Pravda published a picture of a May Day parade with fifteen leaders on the tribune of the Lenin Mausoleum, with Stalin standing third from the left, between Budyonny and Falaleev. Many were in uniforms with numerous medals; Stalin was dressed more simply, in his marshal’s greatcoat. Several leaders including Stalin were saluting the parade with their right arms. On the same front page was a typical picture of Beria, Stalin, Malenkov, Kaganovich, Kalinin, Mikoian, Shvernik, Voroshilov, and Voznesensky “walking to Red Square” from the Kremlin.

Figure 2.14. War’s end is imminent and Stalin is back in Pravda. By Boris Karpov. Pravda, 1 May 1945, 1.

On the day of the German capitulation, 9 May, soon to join the canon of holidays as Victory Day (Den pobedy), Pravda showcased on page three a drawing by V. Andreev that depicted a beaming soldier with an automatic rifle, holding a flag with a Stalin portrait, with the Kremlin tower in the background and fireworks in the sky. The slogan of the day reads: “Long live our victory!” One day later two-thirds of the front page were occupied by an image of Stalin by V. Bulgakov.96 This image shows a graying Stalin in his marshal’s uniform with the single Hero of Socialist Labor medal, holding a pipe in his left hand and papers in his right hand. On the lower left part of the page is a picture of Stalin, Truman, and Churchill. The rest of the right-hand front page is taken up by an “Address of Comrade J. V. Stalin to the People” on the German capitulation (Fig. 2.15).

On 13 May 1945 Stalin and his magnates were again staged on the mausoleum tribune, this time at A. S. Shcherbakov’s funeral. According to the caption, the photo showed “The funeral of A. S. Shcherbakov, Comrades Aleksandrov, Shvernik, Gorkin, Golikov, Stalin, Voroshilov, Malenkov, Beria, Andreev, Kaganovich, Voznesensky, and Budyonny on the tribune of the mausoleum during the funeral procession (traurnyi miting). Comrade Popov is making a speech.”97 By this time at the latest both domestic and foreign observers (Kremlinologists) were trying to obtain cues about the current hierarchy of the Party leadership below Stalin by studying the grouping of men around him and, discounting the military men Voroshilov and Filipp Golikov, they would have figured that Malenkov and Beria both had good chances, being placed close to Stalin. In these Pravda representations during May, “the high point of the authority of Stalin” (Elena Zubkova), proximity to Stalin can be read as an indication of high status, even as a pole position in the struggle for succession that was bound to erupt some time in the future.98

The war was over, and so was the heightened seriousness maintained in the country’s leading newspaper. Images of soccer, cows, and the Dnieper hydroelectric power station all returned to Pravda. As if to make up for his low profile during the war years, during the summer of 1945 Stalin was all over the newspaper. The official victory parade on Red Square on 24 June was duly celebrated in Pravda one day later. On 27 June the front page announced that Stalin had received the title Hero of the Soviet Union. On 28 June Pravda’s front page carried a repeat portrait by V. Bulgakov on the occasion of the presentation to Stalin of “the highest military rank—Generalissimo of the Soviet Union (vysshego voinskogo zvaniia—Generalissimus Sovetskogo Soiuza),” and on page two, an image showing a soldier reading aloud this decree to his happy comrades. The postwar generalissimo image of Stalin, which had been gestating since at least early 1941, now reached its fullest expression.99 Stalin’s hair and moustache had definitively turned gray, he looked weathered by the war, his skin appeared older, his entire face somewhat puffy, his chin unmistakably double. He was habitually dressed in his marshal’s uniform and greatcoat, with the single pentagram-shaped Soviet Hero of Socialist Labor medal, often with his hands behind his back. On 1 August Stalin made his first appearance in his white generalissimo uniform with five golden buttons and epaulettes.100 The occasion was the Potsdam Conference. In this picture (and in two more photographs of the conference) the white color of his uniform and his position in the picture set Stalin apart from his Western counterparts, Harry Truman, Winston Churchill, and Clement Attlee.101 In an August 1945 picture of the Soviet leadership with General Eisenhower and Averell Harriman on the tribune of the Lenin Mausoleum during a Physical Culture parade, for the first time the white uniform spread from Stalin to other Party luminaries.102 In pictures of various Party or Supreme Soviet congresses, Stalin was now often seated all by himself, appearing aloof, sometimes in a corner of the auditorium.103

Figure 2.15. Front page the day after Germany’s capitulation. Pravda, 10 May 1945, 1.

It was only a small step from this aloofness to complete absence. Thus in the photograph of the tribune of the Lenin Mausoleum during the Day of the October Revolution 1945, Stalin was missing among his cronies for the first time in years.104 Thereafter he made one last appearance, in 1952. There might have been real-life explanations for this change, such as his frail health. However, to Pravda readers this change announced a shift toward absent representations, as in Chiaureli’s movie The Oath (1946), where in a famous scene Lenin’s spirit was transferred to Stalin at a park bench in Gorki;105 or as in Pavel Sokolov-Skalia’s painting, The Voice of the Leader, which showed a group of soldiers and others grouped around a radio listening to a Stalin speech. Another example was Dmitry Mochalsky’s 1949 picture, After the Demonstration (They Saw Stalin), which depicted a group of children and others returning from a parade with shining faces—the presence of Stalin in the picture was manifest on the faces of the children and in the title, yet there was no direct representation of him (Fig. 3.12, p. 114). Around the same time in Poland, Party meetings adopted the ritual of electing Stalin to an imaginary honorary presidium and then leaving a chair empty for his spiritual presence.106 Practices such as this one reconnected with premodern (and Byzantine) tradition, for example of using an effigie in France as an ersatz monarch, or of the Rat who in 1791 genuflected in front of an imperial portrait.107 Stalin’s absence hence was an absence that implied presence—“in the spirit,” as an allusion, as a metaphor. Put differently, by being absent, Stalin became more present than ever (for the first—1937— absent representation of Stalin see Fig. 2.16).

In Pravda’s representations of Stalin, the concept of presence-in-absence went hand in hand with the rise of the radio. In conjunction with the 1947 elections to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, not only was Stalin shown at a rostrum with microphones on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater, but an article described enraptured audiences gathered around radio receivers, listening to their leader’s voice emanating from Moscow, the center of the vast Soviet Union.108 Likewise, the representation of the election results was strictly hierarchical: the announcement of winning deputies listed the Russian Republic first, next the city of Moscow, then the election district named “Stalin,” and finally the winner— Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin.

Figure 2.16. The first absent representation of Stalin. “. . . together with his family 1.1. Chernyshev is listening to a radio speech of J. V. Stalin from the Bolshoi Theater. . . .” On the same page there was a series of reports from various union republic capitals under the headline “The Whole Country Listened to Stalin.” Pravda, 12 December 1937, 3.

One year after the end of the war, 9 May had become part of the holiday cycle and Pravda featured on the front page a photograph of Stalin in marshal’s uniform in a wood-paneled room, his left hand behind his back, and his right hand between the buttons of his jacket in the Napoleonic fashion that had become popular in depictions of Party leaders in the early 1930s and had trickled down to smaller authority figures in factories, mines, and kolkhozes (Fig. 2.17, 2.18). In general, after the war the Stalin pictures in Pravda became more repetitive and more closely associated with specific holidays.

Now has come the moment for a closer look at the more cyclical, ritualized, and synchronic quality of Stalin’s representation: the elements that were repeated year after year. It is best to explore one year to follow Stalin’s appearance in the premier Soviet newspaper—1947. This was one of the gray years in the pages of Pravda. By January 1948 the country would get a foretaste of the 1949 anti-Semitic campaign against “rootless cosmopolitanism,” as it learned of the “accidental” death (in fact, the murder by the secret police) of Solomon Mikhoels, director of Moscow’s State Jewish Theater and president of the Jewish Antifascist Committee. True, in 1947 there was a famine in the Ukraine and in the central and southern parts of the Soviet Union, but needless to say, this calamity never made it onto the pages of the newspapers. And yes, the Cold War and the Zhdanovshchina (the era of Zhdanov, of ideological and cultural persecution) with its tireless campaign against Western cultural influences had all begun a year earlier, but 1947 was a year without noisy scandals like the 1946 attacks against Anna Akhmatova, Mikhail Zoshchenko, and the journals Zvezda and Leningrad. The year 1947, as far as Pravda was concerned, was an atypically typical year, no annus mirabilis or annus horribilis but rather a thoroughly quotidian year.

Figure 2.17. Stalin sculpture by M. A. Novoselsky. The Napoleonic hand inside the coat goes back at least to photographs of Marx, whose bourgeois period had domesticated the French Emperor’s gesture. Pravda, 10 June 1936, 1.

Figure 2.18. This is one of several examples of the dissemination of the Napoleonic hand gesture to the new Stalinist heroes, in this case a kolkhoz activist. Pravda, 2.2. October 1933, 3.

There were 42 visual representations of Stalin in Pravda during 1947, compared with 53 representations in 1945, 39 in 1946, 35 in 1948, and 35 in 1949 (Graphs 2.4). This was a far cry both from the prewar all-time high of 142 Stalin pictures in 1939 or a still-impressive 92 in 1937 at the height of the Great Terror, a time when the public Stalin cult was supposedly scaled back, and from the wartime lows of, say, 21 in 1942. Precisely because of its grayness and typical qualities, 1947 is a good year to peer across a Pravda reader’s shoulder, navigating through the newspaper.

Graph 2.4. Visual Representations of Stalin in Pravda, 1947

The lead article on Wednesday, 1 January 1947, was headed simply “1947” and began with the words, “At midnight the Kremlin’s Spassky Tower clock announced the end of one year and the beginning of another. The hearts of the Soviet people were filled with a feeling of calm confidence at the sound of the Kremlin chimes. Time is working for us!”109 In the rest of the article there was a lot of talk about Stalin and how the Soviet Union, under his guidance, was catching up after the wartime devastation. The same was true for the remainder of the paper, but there was no picture of Stalin. The only pictures were photographs of the Dnieper hydroelectric station and the restored S. M. Kirov mill, destroyed during the German occupation, in the town of Makeevka in the Ukraine’s Stalin oblast in the Don Basin, accompanied by an article by Pravda’s Stalino-based correspondent. Consider the use of “Stalin oblast” and “Stalino”—just as movement through Soviet space had become impossible without encountering Stalin coordinates, movement through the leading Soviet newspaper had become impossible without encountering Stalin’s name. But there was no picture of Stalin published on this first day of the year 1947.

This too was typical. Usually neither the 31 December issue nor the 1 January issue featured an image of Stalin. On December 31 there might be seen a picture of a New Year’s tree and on the first of the year a photograph of Moscow’s illuminated Red Square and the Kremlin’s Spassky Tower headed “Moscow on New Year’s Eve.” In general by 1947, in fact by 1939 at the latest, there was much less of a sense of flux as a canon of Stalin images and a schedule of their appearances had been formed. His representations in Pravda adhered to a certain rhythm, which more or less followed the calendar of Soviet holidays. Year after year Stalin appeared on the same occasions and the same holidays—often with the same pictures. Apart from these representations at the high points of the Soviet festive calendar, Stalin appeared on other occasions such as in a photo with a visiting a foreign dignitary, or at an extraordinary Party congress, or of one of the many Soviet election rituals. But what remained stable, what structured Soviet time, what lifted the kairotic above the chronological, were Stalin’s ritualized holiday appearances.110 It was around these holidays that the year revolved.

Most often Stalin made his first appearance of the year on 21 January, in the issue devoted to the anniversary of Lenin’s death.111 Here he was shown with Lenin in a classic 1922 photograph at the government country estate in Gorki. Lenin was ailing after his first stroke of late May 1922. In the photo, Stalin is dressed in a white army overcoat and sitting in a vigorous-looking pose with his legs apart, while Lenin is somewhat in the background, dressed in a gray army overcoat, his hands folded and his legs crossed.112 The picture suggests one man, Stalin, about to leap, ready for action, while another is sitting back.113 In 1947, instead of this photograph, Pravda featured a drawing of Lenin by Pavel Vasiliev in the upper left-hand quarter of the first page and a drawing (also by Vasiliev) of Stalin and Lenin in the upper left-hand quarter of page two. The drawing showed Lenin and Stalin seated at a table with a newspaper, Lenin in three-quarter view further back and ambiguously gazing both at a point outside the picture and at Stalin. In the foreground is Stalin in side view, looking down at the newspaper (Fig. 2.19). As so often, the theme was that of Stalin as Lenin’s legitimate heir, of Stalin as the follower of Lenin’s ideas. In 1947, a merely ritualistic invocation of this theme was necessary, since Stalin had long ago become self-referential and no longer needed to refer to Lenin as a source of legitimacy. A long article entitled “The Great Friendship” ends by citing a piece of Soviet folklore: “The banner that Lenin raised above us, / Neither years nor centuries will shake. / Time marches firmly like a trusted horse, / The years go by and we move forward. / Along those paths that Lenin bequeathed to us, / Dear Comrade Stalin leads us.”114 The article ended by proclaiming, “This is what the Soviet people say in their epic. They see the embodiment of the Leninist ideas, of the Leninist beginning in his worthy pupil and comrade-in-arms, in the great continuer of his cause. ‘Stalin is the Lenin of today,’ they say.”115 Other photographs, drawings, or reproductions of paintings might also be shown on this day. Sometimes there were facsimile reproductions of “new” archival documents linking Lenin to Stalin, such as a Lenin telegram or letter addressed to his onetime disciple.116 The resounding message in all representations on this day was encapsulated in the classic slogan, “Stalin is the Lenin of today.” The 22 January picture of the Party leadership at the Lenin commemoration—on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater with a huge Lenin portrait in the background—drove home the same message: despite the entire Party leadership’s presence, Lenin’s gaze again was directed both into the distance and at Stalin, whose gray generalissimo’s uniform distinguished him from his black-clad magnates.

Figure 2.19. The anniversary of Lenin’s death and Stalin’s first visual appearance in the annual holiday cycle. Drawing by Pavel Vasilev. Pravda, 21 January 1947, 2.

Stalin’s next holiday appearance was on 23 February, the Holiday of the Red Army (later Day of the Soviet Army), an important occasion celebrating the founding of the Red Army in 1918. It was important, but not as holy a day as the two highest holidays, International Workers’ Day on 1 May and Day of the October Revolution on 7 November.117 On 23 February 1947 a quarter-page photograph showed Stalin in his parade greatcoat with a fur collar and his parade cap with a (probably gold-colored) cord and single Soviet star button. He peered attentively and pensively both at and past our imaginary Pravda reader (Fig. 2.20). His gaze seemed as if he was spotting new military foes of the state he embodied, or pondering the future that he—as the embodiment of history— was able to foresee. To the left of his picture was a long decree that consisted mostly of a summary of the Soviet Army’s achievements but closed with the following words:

In commemoration of the twenty-ninth anniversary of the Soviet Army I decree: Fire a twenty-gun salute in the capital of our motherland, Moscow, in the capitals of the union republics, in Kaliningrad, Lvov, Khabarovsk, Vladivostok, Port Arthur, and in the hero-cities Leningrad, Stalingrad, Sevastopol, and Odessa. Long live the Soviet Army and Navy! Long live our Soviet government! Long live our Communist Party! Long live our great Soviet people! Long live our powerful motherland!

Figure 2.20. Stalin on the “Holiday of the Red Army.” The caption describes him as “Minister of the Armed Forces of the USSR and Generalissimo of the Soviet Union.” Pravda, 2.3 February 1947, 1.

The decree was signed “The Minister of the Armed Forces of the USSR, Generalissimo of the Soviet Union J. STALIN.”118 Often on this day Pravda featured a picture of Stalin on the tribune of the Lenin Mausoleum taking the salute at a parade of soldiers and heavy military equipment on Red Square. Frequently he was joined by Voroshilov. The message on this day was one of Soviet military might, of preparedness to fend off any outside attack, and of Stalin’s embodiment of the Soviet Army. This was a new role he had assumed during World War II. Before then Stalin embodied the state only, and Voroshilov the Red Army, which in turn protected Stalin. But with the war, Stalin had assumed this new double role, embodying both state and army, thus superseding whoever was commissar of war.