Only three years after his victory at Hastings, William the Conqueror’s grasp on his new kingdom appeared to be failing. In the summer of 1069 Danish troops landed on the north coast, where they were joined by a large force of English rebels. William forced his army through to York, where he spent Christmas. From there he sent messengers south to fetch not arms, or more men, but his crown. Christmas was one of the three annual occasions – the others being Easter and Whitsun – at which the King of England appeared ceremonially at court, wearing his crown. This tradition, which went back to Charlemagne, and before him to the emperors of Byzantium, had been established in England in Saxon times. The Conqueror, eager to proclaim his legitimate claim to the throne, was punctilious in his observance of this ancient assertion of regal identity. It was far from surprising, therefore, that in the midst of war, and in a city that had been sacked by the Danes, William should care about his crown. His respect for royal ceremony was an important aspect of his campaign – by persuasion, as well as by force – to be accepted by the English as their king. He succeeded: the Danish army sued for peace, and William brutally suppressed all opposition in the north of England.

Throughout the centuries that followed, all monarchs understood that it was not enough to be a ruler – they had to look like one. An essential attribute of their public standing and authority was ‘magnificence’, or the visual expression of wealth and power. On one occasion, neglect of this imperative may have contributed to the loss of a kingdom. In the civil strife that has come to be known as the Wars of the Roses, Henry VI (1421–71), head of the house of Lancaster, was usurped in 1461 by Edward, Duke of York, who became Edward IV (1442–83). In 1470, shifting aristocratic allegiances led to Henry being restored, forcing Edward to flee to Burgundy, from where he returned a year later with an army. Henry’s allies tried to rally support for him by taking him in procession through the streets of London. However, because it was Maundy Thursday, Henry was dressed in ‘a long blew goune of velvet’, an appropriately plain garment for a solemn day. That point was lost on the crowds, who thought he no longer had royal dress, which would have been gold, crimson and ermine. One supporter of Edward IV wrote that the procession was ‘more lyker a play than the shewing of a prynce to wynne mennys hertys’.

Edward’s army entered London unopposed, and he confirmed his victory by having Henry murdered. Edward didn’t make his predecessor’s mistake when it came to his appearance. Following the state opening of his first parliament after his return to the throne, Edward went in procession, wearing his crown, to Westminster Abbey. There he made offerings at the shrine of his namesake, Edward the Confessor, England’s royal saint, whose feast day it was. Regal piety and liberality were combined with magnificence as a way of announcing that the new dynasty was here to stay.

Any account of the Royal Collection should begin with the crown. It forms part of the regalia, or Crown Jewels, which are the fundamental physical attributes of monarchy. They are made of precious metals and jewels to symbolise the belief that the monarch is not only the supreme source of political authority but is also divinely consecrated by anointment at the coronation, on the biblical model of King Solomon, who was annointed by Zadok and Nathan, as Handel’s coronation anthem Zadok the Priest reminds us. By extension, therefore, royal identity is embodied in objects of splendour appropriate to a monarch’s sacred status: not just gold and jewels, but also magnificent apparel, imposing buildings and splendid possessions – the origins of the Royal Collection.

Although the regalia are most closely associated with coronations, the ceremonies enacted by William the Conqueror at York in 1069 and Edward IV at Westminster in 1472 demonstrate the stress that was placed on all displays of these signifiers of royal authority. There had been one important change in the four centuries between those two events. The crown and other regalia were kept at Westminster Abbey, the setting for every coronation since 1066. The abbey church had been built for Edward the Confessor (1003–66), who was buried there. In 1161 Edward was canonised, which meant that his tomb became a shrine and all objects associated with him were now religious relics. According to the monks of Westminster, the crown had been Edward’s, and was, therefore, too sacred to be worn except for coronations. As a result, monarchs commissioned another crown for their ceremonial appearances, known as ‘the great crown’. This arrangement, which survived the Reformation – and consequent dismantling of the Confessor’s shrine and discarding of his relics – has continued to the present day. Elizabeth II was crowned in 1953 with St Edward’s Crown, but has not worn it since. When she appears in state, most regularly for the opening of parliaments (in a tradition well established by the late Middle Ages), she wears the Imperial State Crown, made for her father, George VI, the ‘great crown’ of modern times (fig.1).

Unlike William the Conqueror and Edward IV, Elizabeth II could not be crowned with Edward the Confessor’s own crown, since in July 1649 it had been destroyed by order of parliament, six months after the execution of Charles I (1600–49). Whereas Charles I’s art collections were largely sold in the new republic, the regalia were such potent symbols of royalty that they were singled out to be ‘totally Broken and defaced’. St Edward’s Crown was stripped of its jewels and melted down for its gold, to be used for making coins. The present St Edward’s Crown (fig.2) was made in 1661 for the coronation of Charles II (1630–85), following the restoration of the monarchy the year before. It is, therefore, as much a symbol of the severing of royal tradition as of its continuity.

Only one piece of the medieval regalia has survived: the coronation spoon (fig.3). Made between 1150 and 1200 it is first recorded with St Edward’s Crown at Westminster Abbey in 1349, when it was described as being of ‘antique forme’. Although it is not mentioned in descriptions of medieval coronations, the spoon may have been used in the same way that it is today, to hold the consecrated oil immediately before the anointing: the unusual divided bowl seems designed for two fingers to be dipped into it. It was sold in 1649 (for 16s) to Clement Kynnersley, one of Charles I’s yeomen of the wardrobe, who returned it to Charles II so that it could be used at his coronation in 1661, at which point pearls were added to the stem.

The placing of these pearls on this precious object has a symbolic value in the history of the Royal Collection. They mark the moment not just of the re-establishment of the monarchy but also the beginning of the continuous history of the Collection after it had been fractured in the Commonwealth. The year of Charles I’s execution, 1649, was a disaster for not just the British monarchy but also its collections – with few exceptions, the King’s treasures were sold or destroyed. Regret for that loss usually focuses on the paintings and sculptures that Charles had commissioned or bought, but the sale included almost everything he had inherited from his royal ancestors, stretching back to medieval times, with the significant exception of items he had himself sold, melted down or given away. Although from the moment of Charles II’s restoration, items that had been in the Collection before 1649 began to return to royal hands, and although subsequent monarchs and their families up to the present day have occasionally bought back works of art dispersed after Charles I’s death, it would be impossible to recreate the collection as it had evolved up to then. For that reason, telling the story of the Royal Collection is like reading from a book that has had the first half of its pages ripped out. The collection begins with a few items from the reigns of Henry VII (1457–1509) of England and James IV of Scotland (1473–1513); apart from the coronation spoon, there is almost nothing earlier of significance. Even the period of collecting from Henry VII to Charles I is represented only fragmentarily, although some of those fragments, including armour and tapestries as well as paintings and drawings, are amongst the great treasures of the collection. Since Henry’s victory over Richard III (1452–85) at Bosworth in 1485 is traditionally held to mark the end of the Middle Ages, and the beginning of the modern monarchy as first embodied by the Tudors, it could be argued that there is a symbolic value in the fact that the collection does not extend back much before 1500.

In 1486 Henry VII made a royal entry into York. Although nobody at the time would have noticed, there were parallels with William the Conqueror’s arrival there just over four centuries earlier. Henry, too, had won the throne in battle and had to fight hard to retain it. Aware, like the Conqueror, of the need to impress the local populace with his legitimate royal status, Henry staged a crown-wearing ceremony in York on 22 April, and the following day, St George’s Day, he held the annual feast of the Garter, England’s royal chivalric order, founded in 1348.

Like his predecessors, Henry knew that he had to invest in the trappings of monarchy, partly as a way of retaining a throne on which he never felt wholly secure. The constant threat of invasion or usurpation by the claimants and pretenders who afflicted Henry’s reign meant that, far from ending on the battlefield at Bosworth, the Wars of the Roses continued well into the following century. Before Bosworth, Henry’s priority had been to keep out of the clutches of his enemies, most notably Edward IV. As a result, he had little direct experience of life at the English court in the fifteenth century, and so would have relied on the recollections of his wife (the eldest daughter of Edward IV) of the almost stupefying splendour that her father could summon up for state occasions. Henry VII not only matched but also, in many ways, exceeded the standards set by Edward IV. Whereas Edward had concentrated his public crown-wearing at a single ceremony on the Feast of the Epiphany, Henry multiplied this by five, appearing in his regalia at Christmas, Epiphany, Easter, Whitsun and All Saints’ Day. He never neglected public appearances – after the death of his wife and eldest son, he often dressed in black, but always chose the most luxurious materials in this fashionable (and expensive) colour.

Henry’s competitiveness with his predecessors was especially marked in an area eagerly scrutinised by contemporaries: piety. One of the very few works in the Royal Collection that can probably be traced back directly to the King is an altarpiece on panel that he may have commissioned in about 1502 (fig.4). It depicts Henry and Queen Elizabeth, with their seven children – only four of whom survived infancy – kneeling in prayer. Behind them, against the backdrop of a fantastical castle, St George rescues the Princess Cleodoline from the dragon. St George is the patron saint of England, and one of the three patron saints of the Garter (whose collar Henry is wearing).

Despite this emphasis on symbols of England, Henry turned to an Italian sculptor when commissioning the monument that would represent him to future generations. In his will, Henry VII specified that his tomb was to be made by the Modenese sculptor Guido Mazzoni (c.1450–1518), whose design he had approved three years earlier. Henry was no doubt influenced by the fact that since 1496 Mazzoni had been making a tomb for Charles VIII of France. A bust by Mazzoni depicting a laughing boy that appears always to have been in the Royal Collection may have been sent to Henry VII to show what the sculptor was capable of (fig.5). The suggestion that it depicts the young Prince Henry, later Henry VIII (1491–1547), is appealing, but there is no evidence that Mazzoni ever made the journey to England to capture such a startlingly realistic likeness. For unknown reasons, Henry VIII rejected Mazzoni’s design for his father’s tomb and chose the Florentine sculptor Pietro Torrigiani (1472–1528), now remembered primarily as the man who broke Michelangelo’s nose during a fist fight in 1492. Since England was slow to accept the idea, originating in fifteenth-century Italy, that architectural design should be inspired by that of ancient Rome – an idea that is encompassed in our concept of ‘the Renaissance’ – it may seem surprising that an Italian artist of the calibre of Torrigiani should have frequented early sixteenth-century London. Yet he was far from alone. When the successful completion of Henry VII’s tomb was followed by a commission for a tomb on a gigantic scale for Henry VIII himself (never to be finished), Torrigiani returned to Italy to recruit sculptors to help him. Benvenuto Cellini (1500–71) turned down the offer, but Benedetto da Rovezzano (1474–c.1554) and Giovanni da Maiano (1486/7–c.1542) travelled back to London with Torrigiani and had long careers at Henry’s court, not returning to Florence until the 1540s. Work by Giovanni da Maiano (known to the English as ‘John de Mayne’) includes the roundels bearing heads of the Caesars on the exterior of Hampton Court, and Benedetto da Rovezzano fashioned the black marble sarcophagus intended for Henry VIII’s tomb that now houses the body of Lord Nelson in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral.

These sculptors’ work also raises two important issues for the story of the Royal Collection in the sixteenth century, and to some degree beyond. The first is the reliance on foreign artists and craftsmen. This was nothing new; when Henry VII’s tomb was installed in the magnificent new chapel he had commissioned at Westminster Abbey, it took its place in a setting that was almost entirely furnished by foreigners, from its bronze screen by a Dutch or German smith named Thomas, to the stained glass (which does not survive) by the King’s Glazier, Barnard Flower (d.1517), who was Flemish. It may seem odd that foreign craftsmen should have been preferred for a building designed for a monarch who, as the St George altarpiece reveals, was eager to link himself to assertions of English identity. It is doubtful whether Henry VII or Henry VIII would have recognised the argument. Like all great patrons of their time, they simply demanded work of the finest available quality. In his will Henry VII specified that all the vestments and other furnishings of his new chapel at Westminster should be of a quality ‘appertaining to the gift of a Prince’.

The belief that in order to achieve the best it was necessary to employ foreign craftsmen and designers reflects an important aspect of royal magnificence: fashion, or novelty, an aesthetic imperative in the sixteenth century, just as it had been in the Middle Ages. It was an essential part of a monarch’s image that he was as up to date as possible, and more so than his subjects, since he had privileged knowledge of the leaders of fashion abroad – the royal courts of Europe – through gifts, correspondence and diplomatic exchanges. English kings in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries carefully matched their artistic patronage against the standards of the most admired courts in Europe – first, that of the dukes of Burgundy, and then, after the dukedom had been incorporated into France in 1477, the French court. Italian courts were influential also, thanks to the presence in London of not only artists but also merchants and diplomats from Italy.

From the mid-1490s onwards, when the political life of the nation was calmer, and the royal revenues were increasing, Henry VII spent considerable sums on new houses. In 1497 the favourite royal suburban palace, built by Henry V (c.1386–1422) at Sheen, on the Thames, west of London, was badly damaged by fire. Henry VII rebuilt and enlarged it, naming it ‘Richmond’ (before his accession he had been Earl of Richmond). In 1500–1 he demolished a royal manor house named Pleasaunce at Greenwich, east of London, and replaced it with a large new palace, fashionably built of brick and closely modelled on princely houses in Burgundy and the Netherlands. Its design was based on a ‘platt’ (a drawing) ‘which was devised by the Queen’, suggesting that Greenwich Palace’s up-to-date forms reflected the tastes of Elizabeth of York as much as those of her husband.

Only small fragments remain of Richmond, and barely even that of Greenwich, following the demolition of both buildings in the seventeenth century, but contemporary descriptions of their interiors evoke the splendour of Henry VII’s court. A visitor to Richmond in 1501 recorded its tapestry-hung chapel and its great hall, on the walls of which were set ‘pictures of the noble kinges of this realme in their harnes [armour] and robis of goolde’, culminating in a portrait of Henry himself, in a blunt assertion of dynastic legitimacy. Beyond the chapel ‘extendid goodly passages and galaris – payved, glasid and [ap]pointed, besett with bagges [badges] of gold, as rosis, portculles, and such othir’. Heraldic badges – the Tudor rose and the portcullis of Henry’s mother’s family, the Beauforts – were clearly prominent, as on almost all royal commissions. The emphasis on galleries in this description is especially interesting in the context of the Royal Collection. Designed for exercise in bad weather, and to provide views out over gardens from their many windows, they were a fashion imported by Edward IV from Burgundy, and by the sixteenth century were customarily hung with portraits and other paintings.

Even Henry VII’s ambitious programme of palace building was eclipsed by his son. Thanks to the financial security bequeathed him by his father and, from 1536, the vast revenues from the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry VIII was enormously rich. Much of his money was squandered on war, but a great deal was spent on buildings, their decoration and furnishings. He made designs for buildings (as well as armour, armaments and jewellery), and there are references to him being sent architectural drawings for his many projects.

By the end of his reign, in 1547, Henry VIII had built, bought, been given or had expropriated 60 houses. The court had always needed more than one residence because it moved throughout the year, mostly in carefully planned formal progresses, designed to give parts of the country outside London easier access to the court. It has been estimated that in the course of Henry’s 38-year reign the court moved 1,500 times – this mobility explains why, as in medieval times, the royal houses were, in effect, shells, since they were fully furnished with portable furniture, precious plate, tapestries and costly fabrics only when the court was in residence. Many of these items were carried on horse-drawn carts that transported the household to each new residence – in 1541 the French ambassador noted that between 4,000 and 5,000 horses were needed for a move from London to York, where Henry was to meet James V of Scotland.

Few monarchs have ascended the throne of England in such happy circumstances as Henry VIII. Just short of his eighteenth birthday, tall, athletic and handsome, and soon married companionably to his late brother’s widow, Katherine of Aragon, he was fortunate to inherit not only a full treasury but also advisers capable of carrying the main burden of royal administration, leaving Henry to the princely pursuits of jousting, feasting and making war. Among his early priorities, therefore, was to establish a royal armoury. In common with other crafts, the best came from abroad. Henry’s finest early armour was made in the imperial workshops at Innsbruck, and was tailored to him using his doublet and hose, which were sent to Germany for measurements to be taken. By 1511, the King had two armourers of his own, recruited from Milan, who were given a forge at Greenwich. In 1515 their number was bolstered by 11 ‘Almains’ (meaning Germans or Dutch) under the mastership of Martin van Royne. Although most of Henry’s armour was sold for scrap after 1649, a few significant pieces survive in the Royal Armouries and there is also one whole garniture (an armour with interchangeable pieces for different occasions) in the Royal Collection. Mounted and on display at Windsor Castle, it provides an almost unnervingly immediate sense of Henry’s presence (fig.6). It was made in 1540 by one of the great armourers of the age, Erasmus Kyrkenar (c.1495–1567), possibly for the tournament that celebrated Henry’s marriage to his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves (1515–57). Thought to be of German origin, Kyrkenar (or Kirkener) was appointed armourer for the King’s body in 1519 – at an annual salary of £10 – and 20 years later replaced Van Royne in charge of the royal workshops at Greenwich. The design of the engraved decoration on the armour has been attributed to Giovanni da Maiano, a reminder that leading artists contributed to this costly craft.

The level of artistry that could be involved is demonstrated by a hunting sword (fig.7), which, with its accompanying knife, can probably be identified in the inventory of Henry VII’s possessions made after his death in a group of weapons described as ‘iij longe woodknives ij of them of Dego his makinge’. ‘Dego’ was a Spanish decorator of arms, Diego de Çaias (active c.1530–52), who was employed by Henry from 1543 to 1547. Decorated with a depiction of the siege of Boulogne in 1544, the sword is part of a long tradition of Henry commissioning representations of military and diplomatic events of significance to his dynasty, most prominently as large-scale decorative schemes in his houses. The most extravagant way to do this was in tapestry, such as the enormous example, nearly 120 feet long, named the Comyng into Englonde of King Henrye VII, which has not survived. Quite apart from the huge expense of such a one-off design, it cannot have been straightforward to provide precise instructions for the Netherlandish weavers. It was easier to control craftsmen at hand, and in 1532, for example, two painters from either France or the Netherlands, Isaac Labrun and John Rauffe, painted a long mural in a gallery at Whitehall representing Henry VIII’s coronation. Other such subjects from recent history were on panel. In the Royal Collection are a pair of paintings by anonymous artists depicting Henry’s meeting with the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian, in France in 1513, and their joint victory over the French King, Louis XII, at the Battle of the Spurs. Better known are two paintings that depict the events surrounding Henry’s celebrated summit meeting with Louis’s successor, François I, at the Field of the Cloth of Gold at Guînes, near Calais, in June 1520. The painting of the King’s departure from Dover (fig.8) exhilaratingly captures the flamboyance and joie de vivre of the occasion, as well as the King’s pride in his navy. Its companion (fig.9) depicts the extraordinary splendour of the setting for the meeting, which included a temporary palace of wood and canvas to accommodate the King and Queen, the King’s sister, Princess Mary, and Cardinal Wolsey. Since neither painting is listed in Henry’s inventories of portable possessions, they were probably originally set into panelling.

According to the chronicler Edward Hall, every room in the palace at the Field of the Cloth of Gold was hung with tapestries ‘wroughte of golde and silke, compassd of many auncient stories’. It is not quite true to say that Henry’s most valuable possessions were his tapestries, woven with gold and silver thread – on great occasions even these glittering works of art would have been outshone by the displays of his gold and silver-gilt. Yet only a single piece of precious plate made for Henry has survived, a rock-crystal bowl and cover, mounted in gold, enamel, gems and pearls, dating from the 1530s and now in the treasury of the Residenz at Munich. Since Henry’s tapestries incorporated precious metals they risked sharing the fate of his plate, but as they were also needed to furnish rooms their survival rate is much higher. About 120 of the 2,450 tapestries and wall hangings that Henry possessed at the time of his death have survived.

Great care was taken of these costly works of art. The King had his own tapestry works, primarily for making heraldic tapestries and borders, but also for maintaining and repairing the collection. When not in use, tapestries were placed in specially made canvas covers to protect them against dust and moths, and were moved into purpose-built store rooms, fitted with cupboards, racks and ladders, which were kept heated by charcoal burnt in pans, as it was understood that wood or coal smoke damaged tapestries. Efforts were also made to protect tapestries when they were hung: household regulations emphasised that courtiers were not to wipe their hands on them.

Tapestries seem to us intrinsically old-fashioned, and although that is not how they were regarded in the sixteenth century, some of the King’s tapestries must have been regarded as heirlooms: he had inherited 400 to 500 pieces, some of which were at least a century old. It is notable that by the end of the King’s reign, many of the older tapestries were hung at Windsor Castle (always regarded as the most venerable of the royal houses) and so were perhaps already being deployed with antiquarian intent. A similar spirit guided Henry’s major addition to Hampton Court, the great hall built in 1532–4. Such halls were obsolete in terms of their original function, the place where lords dined with their households – Henry never ate there – but they were still potent symbols of an ancient tradition of lordship and hospitality that he wished to acknowledge. Tapestries were an intrinsic part of a hall’s decoration, and it seems likely that a ten-piece set depicting the story of Abraham, made in 1543–4 to a design that may have been commissioned by Henry VIII, was intended for the hall at Hampton Court, where it hangs today.

Although the hall is medieval in its forms, such as the hammerbeam roof, the details of its ornament are classical. There was nothing novel in this by the 1540s; since the 1520s Henry’s palaces had been decorated with painted marbling and moulded friezes imitating Roman carving. Especially fashionable was the painted or carved ornament called ‘antik’, or antique, and usually now referred to as ‘grotesque’, from its origins in the painted ornament in the ‘grottoes’ or underground rooms of Nero’s palace in Rome, rediscovered at the start of the sixteenth century. Tapestries were one important way that Renaissance ornament reached England: for example, in 1542 Henry bought a set of what were called ‘Antique’ tapestries depicting classical gods and heroes woven from a design made for Pope Leo X in about 1520 (fig.10). Also in 1542, Henry bought a set of the tapestries depicting the ‘Acts of the Apostles’ woven from designs made by Raphael (1483–1520) in the late 1510s for the Sistine Chapel. Henry’s set was sold in 1649 and, having been acquired by the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin, was destroyed in the Second World War, but it remains a presence in the Royal Collection thanks to Charles I’s acquisition of seven of Raphael’s original cartoons.

One of Henry’s aims in buying these very modern – and very expensive – works of art was to emulate the splendours of the new palace at Fontainebleau commissioned by his old rival, François I. In about 1538 one of the French King’s artists, Nicholas Bellin (c.1490–1569), born in Modena, moved to London to work for Henry. He had been employed in Mantua, possibly under Raphael’s former assistant Giulio Romano, and had worked at Fontainebleau with such major Italian artists as Rosso Fiorentino (1494–1540) and Francesco Primaticcio (1504/5–70). Bellin may well have advised Henry about the purchase of his ‘Antique’ and ‘Acts of the Apostles’ tapestries, in which case it is possible that Henry knew who Raphael was. As major works of Renaissance art, the tapestries would seem less isolated in their Tudor context if the decorative work that Bellin carried out at Whitehall Palace and Henry’s lavish new house at Nonsuch in Surrey, begun in 1538, had not so completely disappeared. The quality of work that northern monarchs obtained from Italian sculptors is evident in an extraordinarily rare treasure, a small bronze satyr (fig.11) by one of the most famous of all Renaissance sculptors, Benvenuto Cellini (1500–70). It was made as part of a model for his proposed bronze ‘Porte Dorée’ or ‘Gilded Doorway’, which François I commissioned him to make for Fontainebleau in 1542. This would have been Cellini’s first large-scale bronze, but the project was abandoned. It is not known when the satyr entered the Royal Collection, but it may have been soon after Cellini returned to Florence in 1545; its counterpart is now in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

In the early years of Henry’s reign, painters were employed mainly for decorative and heraldic work, often for the temporary buildings and installations required for tournaments or other festivities, of which the palace at the Field of the Cloth of Gold was an exceptional example. In 1527 there were major festivities at Greenwich to celebrate a treaty between England and France. Among the artists employed was a ‘Master Hans’. This was Hans Holbein (1497/8–1543), who, as well as painting a large mural of a battle, was responsible for decorating a ceiling with a depiction of the heavens designed in collaboration with the King’s astronomer, Nikolaus Kratzer. His two stays in London, from 1526 to 1528, and from about 1532 until his death from plague in 1543, brought him, if not great fortune, then certainly great fame.

When Holbein first visited London, the most important painter at court was the Flemish-born Lucas Horenbout (c.1490–1544), who may have begun work for Henry as a ‘pictor maker’ in 1525. ‘Pictor making’ refers to painting on a large scale, but, as it is recorded that Holbein learned the art of miniature painting from a ‘Meister Lucas’ in London (fig.13), it is possible that a very early group of miniature portraits of Henry VIII are by Horenbout (fig.12). They are very close to depictions of Henry in manuscript illuminations. Henry clearly thought highly of Horenbout: his appointment as King’s Painter was renewed after ten years, and Henry recorded his appreciation of his ‘science and experience in the pictorial art’. The high esteem in which Horenbout was held marks the point at which it began to be widely understood by Henry and his courtiers that painting had achieved a new pre-eminence in the visual arts that went beyond its decorative or documentary functions. The promise of Horenbout was to be more than amply fulfilled by Holbein.

There was an immediate demand in London for Holbein’s strikingly realistic half-length portraits, partly because of the fame of one he had painted of Erasmus in 1523. He may have obtained his well-paid work for the 1527 Greenwich festivities thanks to a letter of introduction from Erasmus to one of his regular correspondents, Sir Henry Guildford (1489–1532), comptroller of the royal household, who was in charge of all the arrangements at Greenwich. It is exceptionally appropriate, therefore, that Holbein’s 1527 portrait of Guildford and the preparatory drawing for it are in the Royal Collection (figs 14 and 15). The drawing is one of 80 by Holbein that were collected together in Henry’s reign, probably immediately after the artist’s death, and are first recorded in the Royal Collection in the reign of Edward VI. They were already regarded as a major source for knowledge of Henry’s court, since Edward’s tutor, Sir John Cheke (1514–57), went through the drawings, annotating each with the sitter’s name.

As well as their intrinsic beauty, the drawings possess great importance as documents of Holbein’s working method, since, so far as is known, all were made in preparation for painted portraits. The drawing of Guildford, for example, only summarily indicates major parts of his final portrait, notably the collar of the Order of the Garter. Unusually, the painting is not a precise tracing of the drawing: Holbein manipulated the outline on the panel to make Guildford’s face look longer and leaner, almost certainly on his sitter’s instructions. The drawings are also precious as records of paintings that have been lost. Holbein’s major commission on his first visit to London (1526–8) was a group portrait of Henry’s Chancellor, Sir Thomas More, with his family and household. The painting was destroyed in a fire in the eighteenth century, but a group of Holbein’s studies for the individual portraits survives. They include some of the most sensitive portraits of female sitters by any artist of his time, such as the drawing of More’s ward and future daughter-in-law Anne Cresacre (fig.16).

One of the puzzles of Holbein’s career is the length of time that it took Henry VIII to get round to sitting for him, despite the fact that the King gave him important commissions, such as designing a table fountain to be given to Anne Boleyn in 1533–4. Although Henry is one of the most recognisable monarchs in English history, he was slow to show interest in his own portraiture – he had been on the throne for 20 years before he bothered to replace his father’s image on the coinage with his own. The portraits of himself that he commissioned, such as the Horenbout miniatures, and ‘my picture set in bracelets’ that he gave to Anne Boleyn before their marriage, suggest that small portraits for his intimates counted for more than large-scale, more public paintings.

That all changed thanks to the events that Henry’s desire to marry Anne Boleyn so dramatically precipitated: the severance in 1534 of England’s links with the papacy and the King’s new status as head of the Church in England. Now there was a major incentive for Henry to seek images of himself that would promote this controversial change. The arguments that Henry used to justify his actions are embodied in the only original portrait of the King by Holbein in the Royal Collection, which dates from around 1534 (fig.17). Painted with ravishing delicacy in expensive colours – ultramarine and gold – on vellum, it depicts the Queen of Sheba, a symbol of the Church, addressing Solomon, who has the features of Henry. She is telling him that his royal power comes from God alone, and thus, by implication, does not depend on any other source, such as the papacy. This was a message that people close to Henry, who were sympathetic to Church reform, wanted him to hear, so it is likely that the painting was commissioned as a gift to him.

From then on, Holbein was kept busy painting portraits for the King. After the death of Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour, in 1537, the artist was despatched all over Europe to draw and paint potential brides. Holbein’s portraits of Anne of Cleves encouraged Henry to marry her in 1540, but, so far as we know, the artist took none of the blame for the King’s disappointment when he set eyes on her in the flesh. Two years earlier, Holbein had painted a striking full-length portrait of another candidate for Henry’s hand, Christina, Duchess of Milan, a daughter of the Danish King. Although nothing became of those negotiations, Henry retained the painting, the only portrait by Holbein listed in the Royal Collection when the King died (it is now in the National Gallery, London).

Holbein’s most celebrated portrait of the King has not survived. This was a life-size mural depicting Henry VIII with Jane Seymour and his parents, painted on a wall at Whitehall Palace, probably in the King’s Privy Chamber. It dated from about 1537, and so may have been created to celebrate the birth of the son that Henry had for so long desired, the future Edward VI (1537–53). The four figures, set in a richly decorated classical interior, were grouped around a large stone monument that proclaimed Henry VII as the bringer of peace to his country and his son as the bringer of religious reform: ‘The great debate, competition and great question is whether father or son is the victor. For both, indeed, were supreme.’

The mural was lost in the fire that destroyed Whitehall in 1698, despite desperate efforts to hack it off the wall, but most fortunately in 1667 Charles II had it copied in a small painting by the artist Remigius van Leemput (1607–75), the only complete record of Holbein’s masterpiece (fig.18). Miraculously, the left-hand part of his cartoon – the full-size drawing used to transfer the design to the wall – has survived, and is now in the National Portrait Gallery, London. This reveals that Holbein originally drew Henry looking towards Jane Seymour, but in the finished painting he stared straight out to the viewer in an intimidating depiction of royal authority and majesty. In a biography of Holbein written in 1603–4, Karel van Mander described the portrait as ‘so lifelike that anyone who sees it gets a fright; for it seems as if it is alive’.

Other aspects of Henry’s art collections reflected his new status as absolute ruler of not only England, but also her Church. It seems likely, for example, that the choice of such subjects as the story of David, which featured in the tapestries at all the major palaces, was intended to project an image of the King as patriarch of his people. A few of the paintings also promoted messages of religious reform. Among them is a depiction of the Pope being stoned by the Evangelists (fig.19), painted with a refinement that almost seems inappropriate to the violent subject matter by another Italian artist employed by Henry, Girolamo da Treviso (active c.1497–1544). It is interesting for another reason: this is the only surviving painting that belonged to Henry of which we can be sure exactly where it was displayed. It was hung in the gallery at Hampton Court, which was on the second floor, designed to provide views over the garden and river. Inventories of Henry’s possessions reveal that portraits were juxtaposed with religious and historical subjects without any particular programme; presumably the visitors to Hampton Court who were admitted to this private room of the King’s were expected simply to admire the skill displayed by the artist and perhaps draw a moral, or learn a lesson from the subject. We know that paintings could be moved, since some had specially made leather cases, but usually they were left in place when a palace was not in use, protected by curtains – a mark also of the veneration in which images were held. The curtains at Hampton Court were green and yellow, creating a decorative effect even when the paintings were concealed.

Accounts later in the century record the maintenance of pictures: in 1588, for example, payments were made for varnishing the paintings in the Presence Chamber at Whitehall ‘with a special Varnishe without sente’. Among the paintings listed for this treatment was ‘a greate table [painting] containing King Henrie, Price Edwarde and the ii ladies his daughters’. This painting of Henry VIII and his family, some 11½ feet wide, is by an unknown artist clearly influenced by Holbein (fig.20). It depicts an interior, specially arranged for the painting, at Whitehall Palace, with views out to the Privy Garden. The combination of a painted plaster floor, partly covered by a carpet, with carved and painted decoration and embroidered hangings suggests the almost claustrophobic richness of the interiors of Henry’s private apartments. Less assertive as a dynastic statement than the Whitehall mural, it reflects the calmer tone of Henry’s court under his sixth and last Queen, Katherine Parr. She endeavoured to improve relations between the King and his two daughters, Mary (1516–58) and Elizabeth (1533–1603). Although, like saints in a Renaissance altarpiece, they are depicted separated from their father by columns; it is in this painting that the two women who were to rule England for the second half of the century take their first steps into the spotlight.

Henry’s death on 27 January 1547 was quickly followed by a meeting of his Privy Council. The possibility of selling works from the Royal Collection to raise money for paying the King’s legacies was discussed, but it was agreed that the royal possessions were so important as representations of the wealth of England that any sale of them would be interpreted by foreign powers as weakness. Henry’s children had no pressing motive, therefore, to add to his collections, and in any case it must soon have become apparent that the vast number of houses that he left behind were greatly more than they would ever need.

Although both Edward VI, who inherited the throne at the age of nine, and his eldest sister, Mary, who succeeded him in 1553, had a major impact on the country, as the pendulum of religious obedience swung forcibly toward Protestantism, and then was dragged back to Catholicism, neither lived long enough to leave much mark on the Royal Collection. Edward, clever and precociously interested in theology, as his Protestant revision of the regulations of the Order of the Garter reveals, was never able to commission major works, as he died before reaching the age of majority. An imposing, but sensitive, portrait of Edward, painted for Henry VIII by an anonymous artist shows the prince in a pose that echoes that of his father in Holbein’s Whitehall mural (fig.21). In retrospect this is poignant, since the indications are that Edward, strongly interested in sport and military matters as well as religion, would have grown up to be unmistakably his father’s son.

Mary, by contrast, had to overcome the disadvantages of being the first female monarch since Matilda, daughter of Henry I, in the twelfth century – not a happy precedent, since Matilda’s claim had never been universally recognised. More difficulties were created by the way the Queen courted unpopularity, firstly by her religious reforms and then by her marriage in 1554 to Philip (1527–98), heir to the King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Nonetheless, this alliance with the Habsburg dynasty was a diplomatic triumph, and it brought Mary’s court firmly into the mainstream of European culture. The fine paintings of herself she had commissioned from the Flemish artist Hans Eworth (c.1520–74) were now matched, if not eclipsed, by portraits by Philip’s official painter, Anthonis Mor (c.1520–c.1576), although none of these paintings are now in the Royal Collection.

So that the Queen could see an image of her future husband, Philip’s aunt Mary of Hungary, governor of the Netherlands, sent her a portrait of him by Titian (c. 1490–1576). She specified that it was to be returned, because she valued it so much, and no work by Europe’s most famous painter entered the Royal Collection during his lifetime. However, one outstanding work of Habsburg portraiture produced during Mary’s reign is preserved at Windsor, a bronze bust by the Italian sculptor Leone Leoni (1509–90) of Philip in armour, wearing the collar and badge of the Order of the Golden Fleece (fig.22), which was bought for the Royal Collection by George IV. An inscription on the base describes Philip as King of England, a reminder of a time, often forgotten, when England was jointly ruled by a Habsburg, and Spanish was spoken at court. The terms of Philip’s marriage settlement meant that he had no right to continue as King after his wife’s death. When it became clear that Mary was terminally ill, Philip did his best to smooth the way for Elizabeth’s accession, preferring a Protestant princess to her cousin, the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, who was allied to his enemy, France. Elizabeth succeeded her sister in 1558, and one of her first actions was gracefully to refuse Philip’s offer of marriage.

Despite the great cultural achievements of England during Elizabeth’s long reign, particularly in literature, music and architecture, and despite the fact that she ranks with her father as one of the most immediately recognisable monarchs in history, her contribution to the Royal Collection did not equal his. She never enjoyed his enormous wealth, but of more significance was the fact that as an unmarried woman she came to avoid visual promotions of her dynasty since, almost to the moment of her death in 1603, its future was in doubt. Instead, more strongly even than Henry VIII, she developed a cult of personality – of the Virgin Queen or Gloriana, for which portraiture was an essential ingredient.

The many celebrated paintings of Elizabeth that incorporated allegory and symbolism were made as gifts or were commissioned by her courtiers, and there are very few in the Royal Collection. Among them is a painting dated 1569, which represents a version of the Judgement of Paris (fig.23). The Queen is shown emerging from a palace-like interior to judge the three goddesses Juno, Minerva and Venus, who are nonplussed since Elizabeth outshines them all. This piece of flattery has a double meaning. Its centre is occupied by Juno, who beckons the Queen to follow her. Since Juno was the goddess of marriage, the painting seems to be urging Elizabeth to find a husband. This suggests that it must have been a gift, and it has been proposed that it was commissioned by the Queen’s main counsellor, William Cecil, who was her Secretary of State in 1569. If that is the case, the painting may reflect his anxieties to secure the kingdom at a time of rebellion and plots by Catholic enemies.

The painting is attributed to Hans Eworth, and its assured deployment of allegory reflects his work for Elizabeth as a designer of court festivities: for example, he was one of the artists responsible for a masque staged in 1572 in honour of the French ambassador. Yet, on his death in 1574, the Queen did not replace him, despite the need to control how she was represented, and in spite of requests for her portrait from suitors and foreign rulers; in 1564 the Regent of France, Catherine de’ Medici, was so eager to obtain a good portrait that she offered to send her own court painter to London. One evident change in Elizabeth’s reign is the disappearance of the Italian artists who had been such a familiar feature of her father’s court. Several reasons have been offered for that, such as the growing hostility of Catholic countries, or the decline in Italy’s importance as a trading partner with England. An equally plausible explanation is simply the fact that the Queen was a much less active and generous patron of the arts than Henry VIII had been. When a leading Italian painter, Federico Zuccaro (1540/2–1609), visited London in 1574, he was granted a portrait-sitting by the Queen, but the only result was a drawing (now in the British Museum) that had no influence at all on the way she was portrayed in England.

This suggests that Elizabeth had no deep interest in the visual arts, a supposition that is strengthened by the only contemporary account we have of her sitting for a portrait. The artist Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619) recalled that when she had first sat for him, she asked why Italian painters did not use shadows in their paintings. This reveals a remarkable lack of knowledge, since subtle manipulation of shadow and light – or chiaroscuro – was one of the fundamental elements for which Italian artists were most admired. Hilliard, who seems to have been equally ignorant about Italian art at this early stage in his career, replied that ‘hard shadows’ were only important for large paintings designed to be seen from a distance, whereas they weren’t necessary for the small ones, in which he specialised, which were intended to be seen ‘in hand near unto the eye’. Prompted by this observation, the Queen suggested that she should sit for him out of doors ‘in the open ally of a goodly garden, where no tree was neere, nor any shadowe at all’. The result was the even light and emphasis on line rather than modelling that distinguish Hilliard’s series of miniatures of the Queen. Dating from the 1560s to after her death (since he executed posthumous portraits of her), they form the only sequence of portraits of the Queen by a leading artist that can be compared in significance with those that Holbein had made of her father. They allow us to trace the way the Queen chose to be represented, from a young woman, little different from any aristocrat of her time (fig.24), to the bejewelled icon of her later years. In a glittering miniature painted by Hilliard in the final decade of her reign she appears as Astraea, the classical goddess who presided over the Golden Age (fig.25).

Such portraits are also records of what were arguably the Queen’s greatest contributions to the Royal Collection, although almost nothing survives of them – her jewels and clothes. An inventory taken in 1587 recorded that she owned 628 pieces of jewellery, most of which would have come to her as gifts, and at her death the royal wardrobe contained some 2,000 dresses. Among the few jewels that do survive are cameo portraits of the Queen. These were common – jewellers in London kept them in stock – and, in settings of precious stones, they were worn by the Queen and her courtiers, perhaps inspired by Roman descriptions of the cameo portraits worn by emperors. The finest examples appear to come from a single workshop that must have been patronised by the Queen, but its identity remains a mystery (fig.26). Painted miniature portraits were also customarily set in jewelled cases. An intriguing glimpse of the way they were stored is provided by the Scottish ambassador Sir James Melville, who in his Memoirs described how, in 1564, Elizabeth took him ‘to her bed-chamber and opened a little cabinet, wherein were divers little pictures wrapt within paper, and their names written with her own hand upon the papers’. She unwrapped a portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots, ‘and kissed it’. This was probably the exquisite portrait painted by the French court painter François Clouet (c.1520–72) on the occasion of Mary’s marriage to the future François II of France (fig.27).

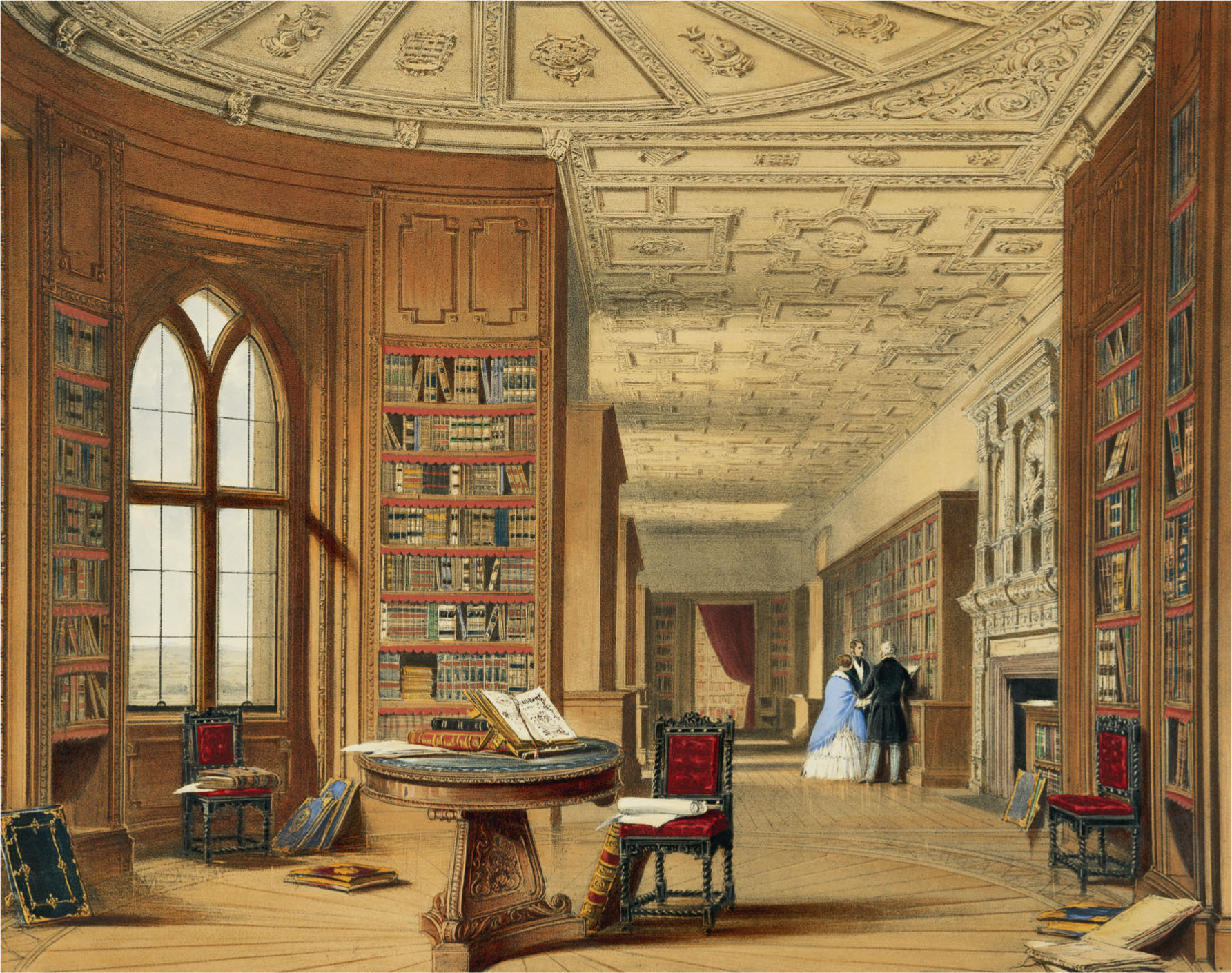

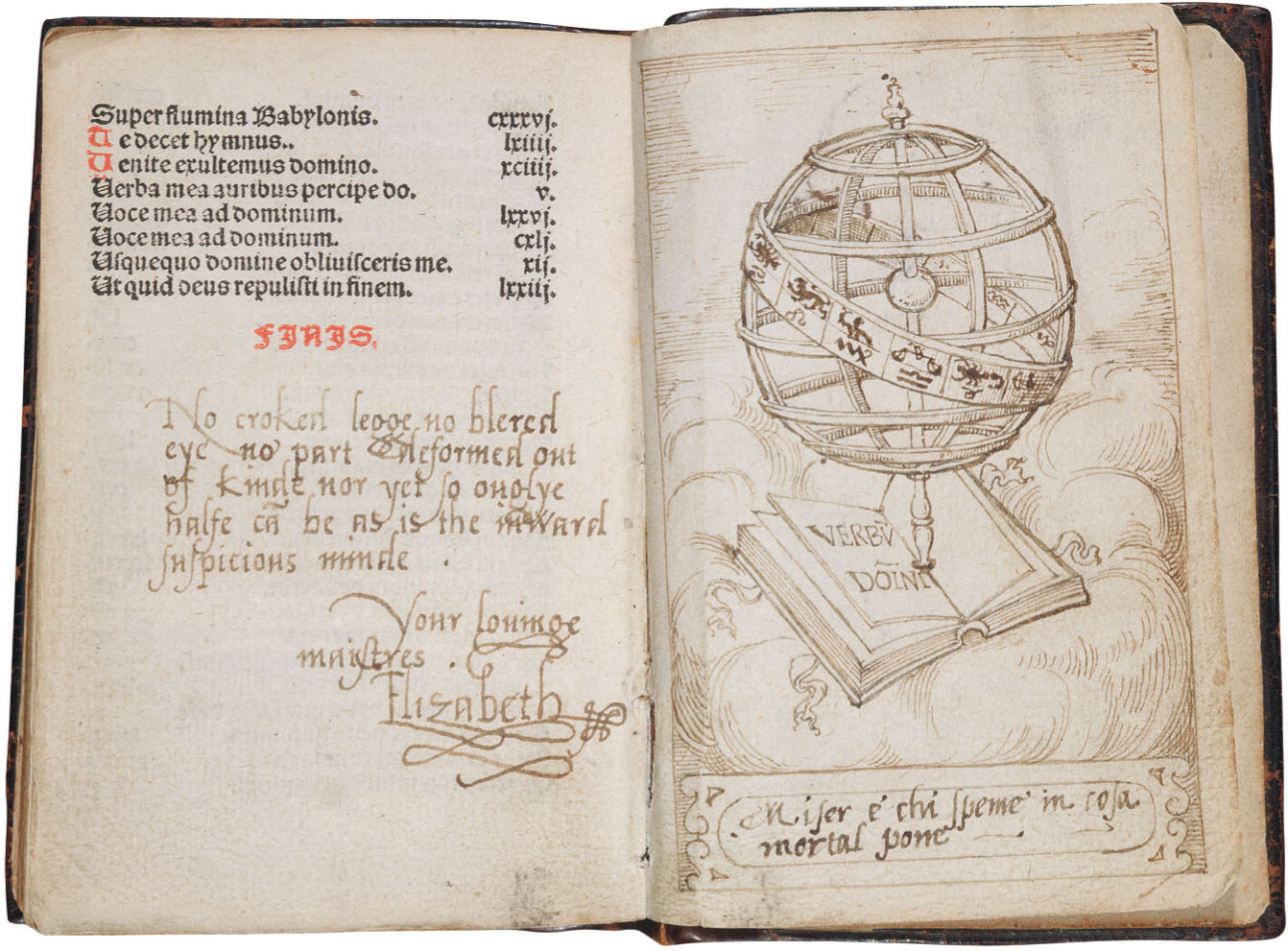

Melville’s visit to the Queen’s private apartments was a privilege, since men were only rarely admitted. Elizabeth was over-supplied with accommodation in the large number of houses she had inherited from her predecessors, and as result she built very little. One of the few major alterations to her residences was the addition in 1583 of a gallery at Windsor Castle. Approached through her bedchamber, this was one of her most private rooms, and although it was converted into the Royal Library in the 1830s, it still preserves a sense of her presence (fig.28). The ceiling, in moulded plaster (a new fashion in the 1580s) is a replica of hers, and her original magnificent stone chimneypiece survives; it was perhaps designed by her architect at Windsor, Henry Hawthorne. The Queen used the Gallery for official business – a couch that she sat on when consulting her ministers was pointed out to a visitor in 1600. It was also a room for reading, and almost certainly contained part of the Queen’s library. Among the treasures of the Royal Library now preserved here is a volume of psalms translated into French and published in the late 1520s (fig.29). Elizabeth has inscribed it with a short poem and the form of signature she used before her accession in 1558. On the opposite page is a drawing of an armillary or celestial sphere, a mechanical representation of the heavens, placed on an open bible, inscribed ‘Verbum Domini’, or ‘The Word of God’ – the apparently mutable created universe is sustained by eternal God. Elizabeth adopted the armillary sphere as one of her emblems, and the possibility that the drawing is by her is strengthened by technical analysis that reveals it is in the same ink as the inscription below it, in her elegant italic handwriting: ‘Miser é chi Speme in cosa mortal pone’ (Wretched is he who places hope in a mortal thing), a quotation from the Italian poet Petrarch.

The Queen would have used her gallery for private study, and so it is likely that it is here that she made the translations from classical literature that occupied her into old age. This was not just a hobby, but an important part of the Queen’s public persona. As a woman, she could not participate in the chivalric and military pastimes that preoccupied her father and brother, but she could share – and exceed – their reputation for scholarship, an admired quality in a prince. Thanks to the excellent education she had received from her tutor Roger Ascham, she was fluent in Latin, Italian, French and Spanish and could read Greek. Her learning was acknowledged in the classical symbolism and allusions employed in the masques, ceremonies and festivities that were an increasingly significant part of life at Elizabeth’s court. In the second half of her reign, the cult of the Virgin Queen as a national symbol was promoted ever more eagerly, partly in defiance of the country’s increasing vulnerability and isolation following the excommunication of the Queen in 1570 and the conflict with Spain that worsened from 1580.

Great artistic energy was poured into the ceremonial tournaments, or tilts, that were staged at Whitehall every year on 17 November, the anniversary of the Queen’s accession. The Royal Collection possesses a beautiful armour intended for these occasions that was commissioned by one of Elizabeth’s handsome favourites, Sir Christopher Hatton (c.1540–91; fig.30). Made by Jacob Halder (active 1576–1609), Master Workman at the royal armoury at Greenwich, it is strikingly decorated with etched and gilt vertical and diagonal bands, scrolls, military trophies, figures and heraldic roses. The temporary sets, decorations and costumes made for the tilts must have been similarly elaborate, but nothing of them survives beyond what can be deduced from a fashion for portraits of the participants in their costumes. One example, painted by the Flemish artist Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (1561–1636) in the late 1590s, evokes the complex symbolism enjoyed by the Queen. This portrait of an unidentified woman in Persian dress, the stag, tree, and even the birds and flowers, all had specific meanings, now mostly lost (fig.31). It has been suggested that the portrait is linked to the entertainment given by Sir Henry Lee, the Queen’s Master of the Armouries and Champion of the Tilt, when Elizabeth visited him at Ditchley, near Oxford, in 1592. This occasion was commemorated in the famous ‘Ditchley’ portrait of the Queen, also by Gheeraerts, now in the National Portrait Gallery.

When Elizabeth died, aged 70 in 1603, she had been on the throne for nearly 45 years and few people had clear memories of her predecessors. Her death led to an immediate demand for her portrait, of which the most popular was commissioned by the London publisher Hans Woutneel from the Cologne-based engraver Crispin de Passe. Showing the Queen full-length, dressed as she appeared at the state opening of parliament, it is based on a drawing of great refinement in pen, ink and wash attributed to the miniature painter Isaac Oliver (c.1565–1617; fig.32). The most copied portrait of Elizabeth ever made, the print became an embodiment of nostalgia for what soon seemed a lost golden age of concord between monarch and people.