Early in Charles II’s reign a new fire-fighting regime was instituted at Whitehall Palace, with orders that a leather bucket had to be kept filled with water next to every chimney. Instructions were issued about what to do if a fire was discovered, including: ‘clap a wet sheet very close against the Mantle and jambes’. In 1691 these precautions proved inadequate when a serious fire destroyed several buildings, including the rooms that had once been so glamorously occupied by the Duchess of Portsmouth. The remainder of the palace was saved only by dynamiting parts of it to stop the fire spreading. Then, on the afternoon of 4 January 1698, some linen that had been left to dry in front of a fire set alight, and within little more than 12 hours most of the palace, with the major exception of the Banqueting House, was destroyed. About a dozen people were killed, but despite the efforts of looters most of the portable works of art and furnishings belonging to the Crown were saved. The major losses were sculpture: Bernini’s bust of Charles I perished, together with, it is assumed, Michelangelo’s Cupid.

It is likely that the damage to the Royal Collection would have been even more severe if it was not for the fact that many of the most important works of art had already been moved elsewhere. At the time of the fire, Whitehall Palace had not been fully occupied by the court for a decade. Its destruction confirmed what was already a major break with the past. In the reign of William III (1650–1702) and Mary II (1662–94) many of the familiar settings for the Tudor and Stuart collections were abandoned: Whitehall and Denmark House (now known again as Somerset House) were never again to be occupied by a royal household, and, at Mary’s suggestion, Greenwich Palace, which had been left unfinished by Charles II, was completed as a hospital for the navy. Even Windsor Castle entered on a long period of neglect, leaving only St James’s Palace as the major link with the past. Instead, ambitious building projects at Hampton Court and Kensington Palace created new settings for the Royal Collection that have continued in use to the present day.

William and Mary’s joint acceptance of the crown in 1689 solved the constitutional crisis that had arisen when James II fled the country in the face of William’s invading army. As far as his enemies were concerned, James had abdicated. On the assumption – almost certainly untrue – that the King’s newborn son was an imposter, the rightful heir was deemed to be Mary, James’s eldest daughter. Since 1677 she had been married to William, Prince of Orange and Stadholder of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, who, as the only child of James II’s sister Mary, was himself third in line to the throne. The joint monarchy was an unprecedented arrangement, but it worked, thanks in part to Mary’s sister, Anne, agreeing to let William take precedence over her in the succession. For the double coronation at Westminster Abbey on 11 April, new regalia and a replica of the medieval throne were made for Mary (fig.109).

William was as decisive about his future homes as he had been in seizing the crown. Although he ordered Christopher Wren to complete the new apartments at Whitehall Palace that had been started for Mary of Modena, he decided that he would not live in the palace. The official reason was that the smoky atmosphere of central London exacerbated his asthma, but it may also be wondered whether he felt comfortable with the palace’s embodiment of the Stuart monarchy. He had got on badly with both his uncles, Charles II and James II, and found their emphasis on their divine right to rule uncongenial. By contrast, on a visit to Hampton Court just a few days after his coronation he saw at once its potential as an alternative to both Windsor and Whitehall. In March he and Mary began to make preparations to move there, and the following month Wren was instructed to prepare designs for rebuilding it. When it became clear that they intended to make Hampton Court their main seat, there were complaints at court about its distance from central London. This prompted William to look for a convenient residence that he could use when business necessitated him being at Whitehall, and so just before Christmas he bought the Earl of Nottingham’s early seventeenth-century house at Kensington, only a short ride from central London, but outside the smog. Wren set to work at once on remodelling a house that was intended to be only a residence. The future Kensington Palace initially had no provision for court ceremony or entertaining – neither of which William enjoyed.

When Mary arrived in England she sent for the designer Daniel Marot (1661–1752), a French Protestant, who had supervised the creation of the gardens at the couple’s hunting lodge in Apeldoorn, Het Loo. Marot’s first recorded work in England was a design for a new parterre at Hampton Court, dated 1689; soon afterwards he was describing himself as ‘Architecte des appartments de sa Majesté Britanique’. In all the media in which Marot designed – from silver and furniture to textiles, painted decoration and gardens – his inspiration was the court taste of Louis XIV. Given that almost all William III’s career was devoted to curbing the French King’s aggressive expansionism, it may seem strange that, in visual terms, court culture in both Holland and England under William and Mary was so indebted to France. Yet the House of Orange was French in origin, and in its drive to be recognised as a princely dynasty – stadholder was in theory an elected office – it had modelled its patronage on French royal precedent. One of the finest portraits of William as a young man, by the House of Orange’s court artist Jan de Baen (1633–1702), shows him decoratively dressed as a Roman soldier as though he were about to take part in a play or opera on a classical theme, like those performed at Versailles (fig.110).

The painting also demonstrates the impact of Anthony van Dyck on aristocratic portraiture in the Netherlands. William had plenty of opportunity to see Van Dyck’s work on his visits to London and clearly admired it. In 1688, as his army advanced on London, he had paused to view Wilton House, which contained the Earl of Pembroke’s famous collection of family portraits by the artist. Since, out of loyalty to James II, Antonio Verrio refused to work for William and Mary, William appointed Godfrey Kneller as his principal painter (initially in conjunction with John Riley, who died in 1691). Kneller’s reverence for Van Dyck made him the ideal painter for the official portraits that were required by the new monarchs. They were indebted to Van Dyck, whose influence is also evident in Kneller’s group of full-length portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’.

These paintings are the result of Queen Mary’s request that Kneller paint for her the most beautiful women at court, resulting in a set of eight portraits that she hung at Hampton Court. At Kneller’s suggestion, the series was confined to English women (so excluding Dutch courtiers), ‘for the credit of the nation’. Much later it was recorded that Lady Dorchester told the Queen that limiting the series to beauties was a mistake: ‘Madam, if the King were to ask for the portraits of all the wits in his court, would not the rest think he called them fools?’, but even if the story is true, there is no evidence that Mary paid attention. The commission emulated Peter Lely’s ‘Windsor beauties’, assembled by Mary’s mother 30 years before. Mary herself had been painted by Lely when she was Princess of Orange, a portrait that shows that she was influenced by French fashions in dress and hairstyle, recalling the Francophile tone set at Charles II’s court by the Duchess of Portsmouth when Mary was a girl (fig.111). It is notable, therefore, that the Hampton Court beauties owe so little to Lely. Kneller’s portraits are not three-quarters but full-lengths (fig.112), evoking the precedent of Van Dyck’s major female portraits, and Kneller – no doubt aware of the criticism that Lely made all women look alike – distinguished his sitters in pose, as well as costume and accessories.

More significantly, Kneller avoided the seductive eroticism with which Lely had depicted the Windsor beauties, which must be a reflection of the wishes of the new monarchs. On his first visit to London to meet his uncles, in 1670–71, William had been horrified by the debauchery of court life, hating in particular the heavy drinking in which he was expected to participate. Morally, he did not lead a blameless life – he kept a mistress and his favouritism towards Dutch friends led to accusations of homosexuality – but the tone of the court during the first part of his reign was as different from Charles II’s as he could make it. He was encouraged in this by Mary, a pious woman who was concerned about raising standards of public morals. Her warmth of personality and candid expressions of loyalty to England helped to compensate for William’s lack of charm and the suspicions of the English court that he placed Dutch needs first. As a result, although the new King was ready to stress his Stuart ancestry, he looked back primarily to his grandfather, Charles I, and the example of his decorous court and happy marriage. He commissioned a bust of Charles I, attributed to the court sculptor Jan Blommendael (1650–1707), which he paired with one of himself (they are now at Windsor) and William’s full-length state portrait by Kneller is virtually identical to Van Dyck’s of Charles I, painted half a century earlier. William emphasised that royal patronage of Kneller was to be compared with Charles’s of Van Dyck by knighting the painter in 1692, and in 1699 he gave Kneller a gold medal with the royal image on it and a gold chain, like those Charles had given to his principal painter.

Continuity with the past was also a theme of the reconstruction of Hampton Court, where work began in April 1689. Because the palace was used by the court only until 1737 and was preserved with few major changes after that, the interiors created there by William and Mary can still be experienced. Many of the original furnishings, including William III’s state bed, survive in situ, and others have been brought back or reproduced as part of a restoration of the palace by Historic Royal Palaces following a serious fire in 1986. Prior to 1700 the history of the Royal Collection is one of works of art that, with very few exceptions, have become divorced from the contexts for which they were made or acquired, but from the completion of William and Mary’s work at Hampton Court it encompasses surviving furnished interiors.

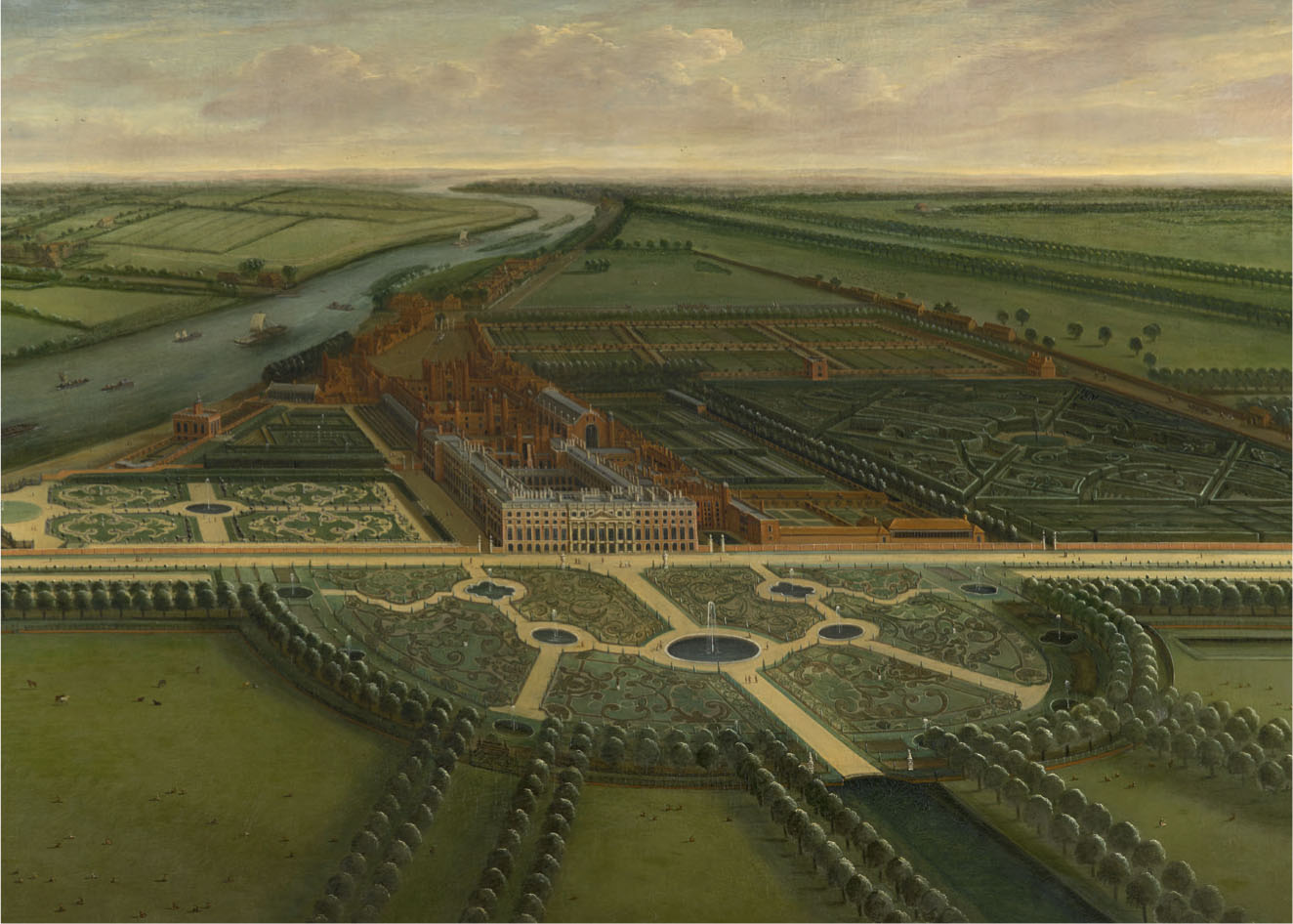

Wren’s first proposal for the palace had been an entirely new building, with echoes of both Versailles and the Louvre, but William and Mary could not wait the many years that construction would take, and decided instead to retain a large part of the Tudor building. However, even Wren’s first design had proposed keeping the great hall, almost certainly as a mark of respect for one of Henry VIII’s major commissions. The architecture of the remodelled Hampton Court was intended to suggest a new dynasty emerging out of the roots of the old (fig.113).

Respect for the past is also evident in the way the new palace was furnished. The fundamental element was tapestry. William and Mary had new tapestries woven in Brussels, of which two fine armorial hangings designed by Daniel Marot are in the Royal Collection (fig.114), but at Hampton Court they used sets of Henry VIII’s Brussels tapestries and some of Charles I’s Mortlake tapestries. This was not necessarily simply a tribute to the past, since there was a general revival of interest in tapestry in the late seventeenth century, thanks to Louis XIV’s foundation of the Gobelins factory, which made tapestries for the French royal palaces. Nonetheless, the choice of works of art for Hampton Court suggests that William and Mary did indeed wish to acknowledge the palace’s historic status. In 1689 William and his secretary Constantijn Huygens (1628–97) drew up a list of the paintings in William’s apartments in all his palaces in order to allow him to allocate them to Hampton Court or Kensington Palace. With few exceptions, the most significant Old Master paintings were sent to Kensington, leaving Hampton Court as it had evolved over the past century as a setting principally for dynastic portraits.

The major exception was the choice of paintings to hang in the new galleries at Hampton Court. Since William and Mary were joint sovereigns, they were given equal accommodation, and both had large galleries. In 1689 they had the strips of the Raphael cartoons laid out for their inspection in the Banqueting House at Whitehall. Delighted with what they saw – Huygens remarked that they were ‘admirably fine, far excelling the prints after them of the best masters’ – they ordered the cartoons to be delivered to the royal picture restorer, Parry Walton, to be glued together and put on stretchers. Mary in addition asked for curtains to be made for them. It took some time to decide where to hang the cartoons, but in 1699 they were placed in the King’s Gallery (fig.115). By then Mary was dead, having succumbed to smallpox in 1694 at the age of only 32, but her recognition that the cartoons needed to be protected from light was respected by the provision of green silk curtains that could be drawn in front of them. At Wren’s suggestion the panelling was carried up behind the cartoons, to help preserve them from damp, and the King ordered a fire to be kept alight in the gallery throughout the winter for the same reason. The Queen’s Gallery was treated similarly. Having taken over the room for his own use following his wife’s death, William hung it with Andrea Mantegna’s The Triumph of Caesar (see fig.46), installed in 1702 after a lengthy restoration by first Parry Walton and then Louis Laguerre (1663–1721), a French painter who had moved to England in 1684 to work as an assistant for Verrio. At the same time, Laguerre was commissioned by William to make copies of the Raphael cartoons, the beginning of a sequence of copying and reproduction in print form that continued throughout the eighteenth century. Within a few years of their installation, the cartoons had been transformed from strips of paper kept in a trunk into one of most celebrated treasures of Western art. Although the room in which they were displayed was intended for court life – William used it for meetings of the Privy Council – it was soon regarded simply as a picture gallery, a significant new development in the role of works of art in the royal palaces.

In the early 1690s Mary visited Hampton Court regularly to inspect progress, and so needed accommodation at a convenient distance from the building works. She decided to remodel the Tudor watergate to form a substantial garden pavilion, known as the Water Gallery. The interiors were decorated by Marot to a coordinated colour scheme – chairs were painted blue and white, curtains were fringed with blue-and-white silk and the set of eight paintings of the Hampton Court beauties were hung here in blue-and-white frames. The reason for this choice of colour was that the decoration took its cue from Mary’s large collection of Delftware, ranging from tiles to vases and dairy wares, which Marot integrated into the decoration (fig.116). The inspiration for the décor was French, in this case the blue-and white interiors of the Trianon de Porcelain built at Versailles for one of Louis XIV’s mistresses, Madame de Montespan.

As Princess of Orange, Mary had developed a passion for ceramics. Delftware – tin-glazed earthenware made in imitation of oriental blue-and-white porcelain – had been developed by Dutch potters from the late 1650s onwards in response to a Chinese export ban on porcelain that lasted until the 1680s. To judge from the survivors of her Delftware, Mary commissioned pieces by leading factories, made to designs by Marot. After her death, William dismantled the Water Gallery and the Delft was redisplayed at Hampton Court. There are also a few pieces in country-house collections, notably Erddig, Denbighshire, and Dyrham Park, Gloucestershire – probably royal gifts or courtiers’ perquisites of office.

Mary collected porcelain with even greater enthusiasm, and brought crates of it with her from Holland. A 1697 inventory of Kensington Palace records no fewer than 787 pieces arranged throughout all nine rooms of her apartment – on mantelpieces, over doorways, on cabinets and on specially made shelves and pedestals. All oriental, since no porcelain was yet made in Europe, it was arranged according to both shape and colour. In the largest room, the 25-feet-long gallery, porcelain took centre stage, as no paintings were hung there. Instead, the walls were covered in scarlet silk brocade spaced out by long strips of embroidery, similar to a set of eight panels designed by Marot that survives at Hampton Court (fig.117). These textiles formed the backdrop to not only the porcelain but also to imported furnishings, including lacquer furniture from Japan and carpets from Turkey or Persia. In Holland, Mary’s enthusiasm for lacquer work led to her ordering imported Japanese screens to be chopped up and set into new furniture. She was chastised for this by Huygens, who, in 1685, having observed that pieces of lacquer had been ‘sawed, divorced, cut, clift and slit asunder’, suggested that the Queen should instead give precise measurements for what she required to the merchants who commissioned such pieces for import.

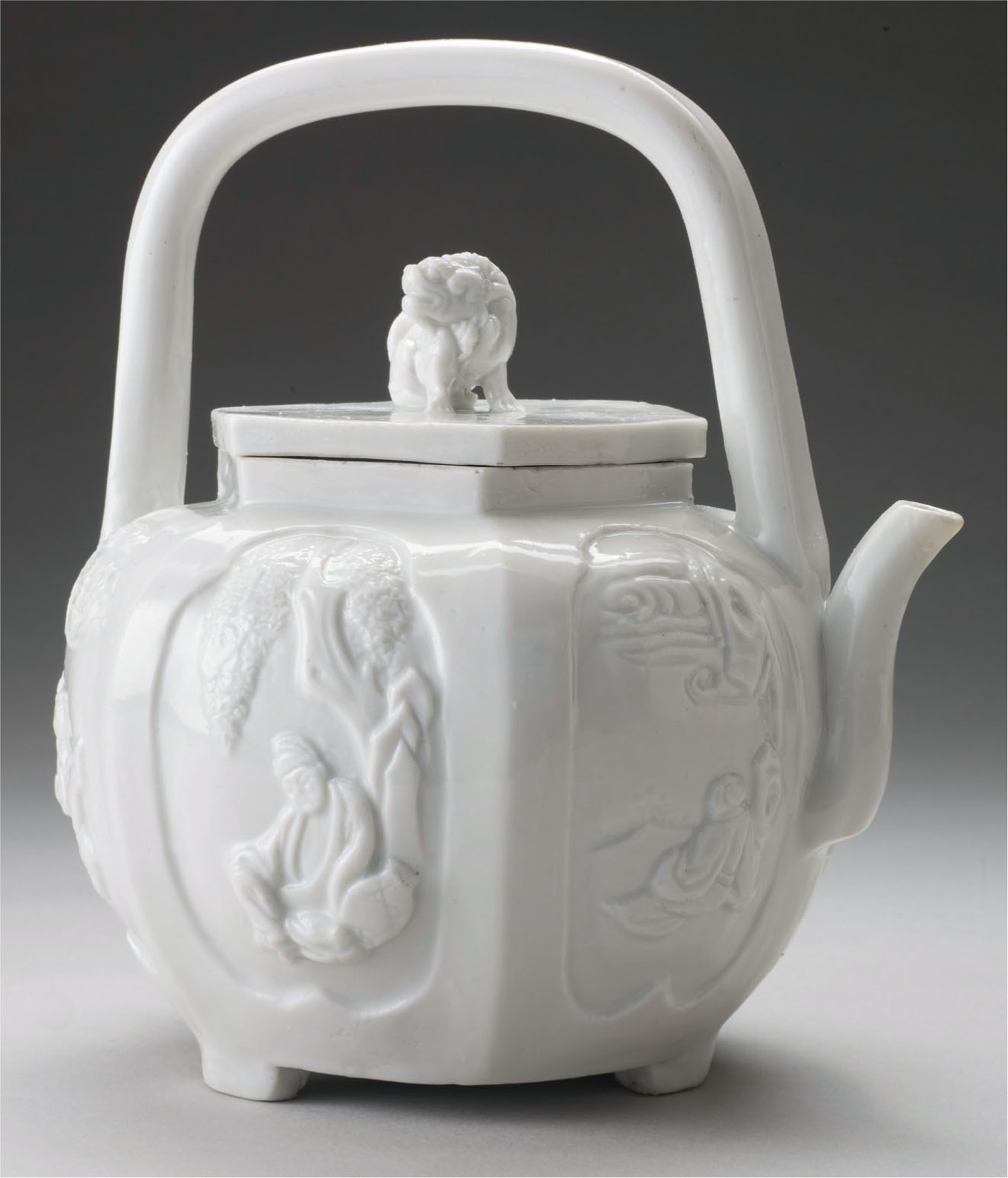

Displays of porcelain were not unprecedented in the Royal Collection – Charles I had shelves specifically made for his 65 pieces at Whitehall – but nothing on this scale had been seen in Britain before. Although it included many ‘useful’ wares – cups and saucers, teapots and even mustard pots – the display was designed for show. Mary kept her porcelain intended for use, notably for the new fashion of tea drinking, in a backstairs closet. It seems likely that a mid-seventeenth-century blanc de chine spouted vessel is the white ‘teapot’ decorated with figures in relief that was listed there in 1697 (fig.118). The display she created did not long outlive the Queen, since in 1699 William gave all the porcelain at Kensington to Arnold Joost van Keppel, 1st Earl of Albemarle (1670–1718), a signal mark of favour to the handsome young man who had become the King’s closest friend after Mary’s death. Keppel installed most of it at his country house, De Voorst, near Zutphen, to judge by the 700 pieces that were there in 1744, when his collections were sold at auction. The only pieces of Mary’s porcelain that can be securely identified in the Royal Collection today are a pair of Chinese mid seventeenth-century, blue-and-white covered jars that have seals attached to their bases impressed with William and Mary’s coat of arms. Nonetheless, this strongly suggests that other pieces of Chinese porcelain that are known to have been at Hampton Court since the eighteenth century also belonged to Mary.

After Mary’s death in 1694 work at Hampton Court stopped for three years, partly because the King was grief stricken, partly because, thanks to his frequent absences, he had relied on his wife to supervise the work, and partly because of a shortage of money that was not remedied until the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 suspended the war with France. In the same year, William ordered work at Hampton Court to begin again, and it was pressed ahead so quickly that in 1700 the court was finally able to move in.

The main responsibility for organising the furnishing of the palace now fell to Ralph Montagu, later 1st Duke of Montagu, who was Master of the Great Wardrobe. He had been Charles II’s ambassador to France and his strongly francophile tastes were influential in London. Most of the interiors at Hampton Court are the work of foreign or immigrant craftsmen, and even the most distinctively ‘English’ element, the decorative limewood carvings by Grinling Gibbons, are by a craftsman trained in the Netherlands. Gibbons’s work was attuned to a characteristically Dutch enthusiasm for naturalistic paintings of flowers, birds and animals, exemplified by paintings by Maria van Oosterwyck (1630–93) that probably belonged to William and Mary (fig.119). By the late seventeenth century, this taste was well established in French, as well as English, courtly circles, and in 1690 the leading flower-painter in Paris, Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer (1636–99), moved permanently to London, and worked for William and Mary at Kensington Palace and Hampton Court. For Kensington he painted a now-lost looking glass with flowers, a novel idea that so intrigued Mary that she insisted on watching him at work. She and William also employed the flower and bird painter Jakob Bogdani (1658–1724) in both the Netherlands and England. Several of his paintings of flowers in elaborate silver or gold vases survive in situ as overdoor paintings at Hampton Court. Montagu oversaw the repair, cleaning and relining of the tapestries William and Mary had selected for reuse at Hampton Court, many of which were given new blue and grey borders, and 6,000 hooks and tacks were ordered for hanging them. Thanks to his influence, the contract for new giltwood furniture was awarded to an immigrant Huguenot firm run by Jean Pelletier (d.1705), whose pier tables for the King’s Apartment were based on published designs for furniture at Versailles (fig.120).

As originally finished, the burnished gilding of this furniture was intended to suggest gilt metal, in a relatively inexpensive echo of the French royal fashion for furniture made of precious metals that had been taken up by Charles II at Whitehall in the 1670s. Louis XIV had been forced to melt down his silver furniture to pay for his wars, which makes the survival of a spectacular suite of silver furniture created for William in emulation of his old enemy all the more precious. Supplied for Kensington Palace by the London silversmith Andrew Moore (1640–1706), the suite was almost certainly designed by Marot (fig.121).

The influence of French royal taste was also evident in William’s liking for furniture inlaid with marquetry of pewter and brass, a technique associated with French royal cabinetmakers such as Pierre Golle and André-Charles Boulle. In London such work was carried out exclusively by an immigrant Dutch or Flemish cabinetmaker, Gerrit Jensen (d.1715), maker of a very fine writing desk made of ebony, rosewood and boulle marquetry (fig.122). Glass-seller as well as Cabinet Maker in Ordinary to the King, Jensen also supplied mirrors to the royal palaces. William asked him to enlarge the mirrors made for his closets at Hampton Court, presumably because he needed more light in the rooms where he transacted private business. Here also he kept other furnishings of practical use, including clocks and – a recent English invention – barometers (fig.123).

The final element of Hampton Court’s interiors was mural painting. By about 1701 William had enticed Antonio Verrio back into royal service, overlooking both his Roman Catholicism and loyalty to James II in favour of creating the sort of relationship that Louis XIV enjoyed with the painter Charles de La Fosse in the decoration of Versailles. Indeed, De La Fosse had worked in London in 1690–92 for Montagu, but had to refuse William’s invitation to participate in the decoration of Hampton Court when he was ordered back to Paris to paint the dome of Les Invalides. Among the first projects Verrio undertook for William, probably in collaboration with Monnoyer, was the decoration of a new banqueting house in the grounds, a scheme that was probably overseen once again by Marot. Verrio then embarked on the ceilings of the King’s Apartment, but only two had been completed when William died unexpectedly of pulmonary fever in March 1702.

William is not remembered as a monarch who helped to shape the Royal Collection, except in a negative way by removing paintings permanently from it. There is no doubt that he was interested in the collection: in his diary, Huygens records conversations about pictures, and William’s order in 1695 that paintings in his private apartments should be hung from cords, implies a desire to be able to rearrange them easily. Although he is not known to have bought Old Master paintings for London, for his Dutch houses he acquired works by, or attributed to, Titian, Sebastiano del Piombo, Rubens and Van Dyck, suggesting a taste close to Charles I’s. He also took a group of about 30 paintings from London to Het Loo. These included Gerrit Dou’s The Young Mother (1658), which the States General had given Charles II in 1660, but the majority were Renaissance portraits, including two by Hans Holbein, one of which depicts Henry VIII’s chief falconer Robert Cheeseman, and two by Piero di Cosimo (1462–1522). The latter are unattributed in the royal inventories but it is possible that William thought they were northern, since in Holland they were described as being ‘in the manner of Albert Dürer’. After William’s death, Queen Anne (1665–1714) tried to get the paintings returned. Although she was unsuccessful, they were, as a result, held back from the sale in 1713 of the stadholder’s art collection, and so most remained in the Netherlands; the portrait of Cheeseman is now in the Mauritshuis and the Piero di Cosimo portraits are in the Rijksmuseum. There is no obvious explanation for William’s choice of these portraits to take to Holland: perhaps he simply selected works of a type that he thought was abundantly represented in London but uncommon in his homeland.

William commissioned relatively few works of art, apart from the flower paintings mentioned above. Despite being a military man, he did not seek depictions of his successes in the field, nor, unlike Mary, did he show much interest in portraiture, whether of himself or others. The one major exception is the equestrian portrait of William painted by Godfrey Kneller in 1701 for the King’s Presence Chamber at Hampton Court, where it remains. This enormous canvas, nearly 4½ metres square, depicts William returning to England in triumph from the negotiations that led to the Peace of Ryswick (fig.124). The painting fits well with the grand allegorical manner of Verrio’s decoration of Hampton Court, but it also looks back to Van Dyck’s portrait of Charles I on horseback. Sold under the Commonwealth, the painting was then in the collection of the Elector of Bavaria, but William hung Van Dyck’s modello for it in his private apartment at Hampton Court (fig.125), together with the paintings of Roman emperors by Giulio Romano that had belonged to Charles. William is largely remembered in Britain as a foreigner, Dutch in his tastes as well as by birth, but to him it was important that he was a Stuart also.

Among Queen Anne’s first acts, after succeeding her brother-in-law, was to refuse to pay for Kneller’s equestrian portrait. This reflected her dislike of William, who had treated her husband, Prince George of Denmark, with contempt – she also rejected statues of William that he had ordered for the gardens at Hampton Court. On the whole, however, she maintained her predecessor’s patronage in the visual arts, although she took much less interest in them than she did in music and theatre. She authorised Verrio to continue the painting at Hampton Court, and Kneller remained in post as her principal painter. Having produced the official portraits of the new Queen, Kneller was asked by Anne to contribute to a series of portraits of 14 of her admirals (now in the National Maritime Museum), on the model of a similar series painted by Lely for her father when he was Duke of York. Yet the fact that she divided the commission between Kneller and the Swedish painter Michael Dahl (1659–1743), who had settled in London in 1689, suggests independence of taste. Further evidence of that is a letter Anne wrote in about 1693 to her close companion Sarah Churchill, later Duchess of Marlborough, reporting on a visit to Dahl in his studio: ‘there was but a few pictures of people I know but those weare very like & the work me thinks looks more like flesh & blood than Sr Godfrey Nellars’. Dahl had been taken up by Prince George, and his principal painting in the Royal Collection is a portrait of the Prince on horseback, painted in 1704 and hung in the Queen’s Guard Chamber at Windsor Castle, a stolid riposte to Kneller’s equestrian portrait of William III.

Although Anne’s reign witnessed great military triumphs under the Duke of Marlborough, little echo of them is found in the Royal Collection. In 1703 she offered an unusual commission to a protégé of Dahl, the Swedish-born miniature painter Charles Boit (1662–1727), whose skill in enamel painting had led him to be appointed enameller to William III in 1696. She asked Boit to paint a large miniature (about 60 x 40 cm), commemorating the Battle of Blenheim. Painting and firing an enamel on such a large scale was a technical challenge that defeated even Boit, and after a decade of unsuccessful experiments he had to return his fee, whereupon debt forced him to move to France. However, he had by then produced for the Queen one of his most ambitious enamels, a double portrait of Anne and her husband, painted from life in 1706 (fig.126). It is a rare portrait of them together, partly because Anne was unable to sponsor paintings of a royal family, since her only surviving child, William, Duke of Gloucester, had died in 1700 at the age of 11.

Portraits apart, Anne’s major acquisition for the Royal Collection was a group of eight paintings by Jakob Bogdani. The purchase echoed William III’s liking for the artist, but there was also an added personal motive for the acquisition. The paintings record the inhabitants of an aviary that Sarah Churchill’s brother-in-law, Captain George Churchill, had built in what is now the Home Park at Windsor, of which he was deputy ranger. After he retired from the navy in 1708, he commissioned Bogdani to paint these scenes of exotic birds and animals (fig.127), which Anne acquired from George’s executors after his death in 1710. The high proportion of birds from South America and the East Indies in the paintings suggests a Dutch source for them, perhaps via the merchants who imported exotic species into Rotterdam. The paintings are an early example of the fascination with natural history that is a prominent theme of the Royal Collection in the eighteenth century.

Anne was undoubtedly conscious of her Stuart inheritance but, unlike her predecessors, she enjoyed a largely harmonious relationship with both Church and parliament. In part due to the circumstances by which William came to the throne, and his continuous need for money for military purposes, parliament had assumed a new centrality in national life. This is conveyed in a painting of the Queen in the House of Lords by Peter Tillemans (c.1684–1734) that was perhaps commissioned by the House (fig.128). Reflecting the new reality of parliamentary democracy, Anne is depicted as a small figure, almost the equal of her peers. Her reign set the course for the monarchy under the Hanoverians, in which the court was no longer the principal seat of political power, and was only intermittently a leading cultural force.