In 1754 Augusta, Princess of Wales, commissioned the Swiss artist Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–89) to make individual portraits of herself and her eight children, together with a posthumous portrait of her husband, Frederick. Liotard’s mastery of pastel won him commissions throughout the courts of Europe, and shortly before visiting London he had made a series of portraits of the French royal family. Yet his works rarely emphasise his sitters’ princely status. Exploiting the way that the softness of pastel can convey every nuance of flesh, he is direct and often unsparing in his depictions of character. This is notably the case with his portrait of Augusta (fig.155). Seeming about to speak, she looks at us sidelong, perhaps a little warily. This was well observed. The three years since Frederick’s death had been full of anxiety. First she had to make her peace with George II after years of estrangement and then persuade him that she could bring up the boy who was now heir to the throne, Prince George of Wales (1738–1820), who was 12 when his father died.

The King’s consent meant that she was responsible for George’s education until he came of age in 1756. Fearful of corrupting influences – especially sexual – she kept him secluded in Leicester House. One of Frederick’s former Lords of the Bedchamber, John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute (1713–92), an expert botanist, was then giving Augusta advice about the garden she was creating at the White House at Kew, which she had inherited on Frederick’s death. Bute got on well with Prince George and, having been appointed his governor, managed to draw him out both socially and intellectually to the point where the Prince came to rely on his ‘Dearest Friend’ completely for advice, in politics and much else. Many of George’s interests – notably astronomy, architecture, mechanics, natural history and book collecting – can be traced back to the influence of Bute, who also helped to develop the Prince’s tastes in art and design.

When George succeeded to the throne on his grandfather’s death in 1760, he was far more sure of himself than anyone could have predicted only a couple of years before. The young King exudes confidence in his first state portrait, painted in 1761–2 by Allan Ramsay (1713–84; fig.156). The choice of artist reflects Bute’s influence: George had already sat for Ramsay in 1758 for a portrait that Bute had commissioned from his fellow Scotsman. By an oversight, the existing Principal Painter in Ordinary, John Shackleton, had been reappointed on the King’s accession, but Ramsay, with the title ‘one of His Majesty’s Principal Painters in Ordinary’ was de facto the King’s painter until Shackleton’s death in 1767. For the next 17 years Ramsay ran what was virtually a production line of official portraits of the royal family in his studio in Soho Square. The demand for them was partly a reflection of the growth of the empire. As a contemporary wrote, ‘The ardour with which these beloved objects were sought for by distant corporations and transmarine colonies was astonishing.’

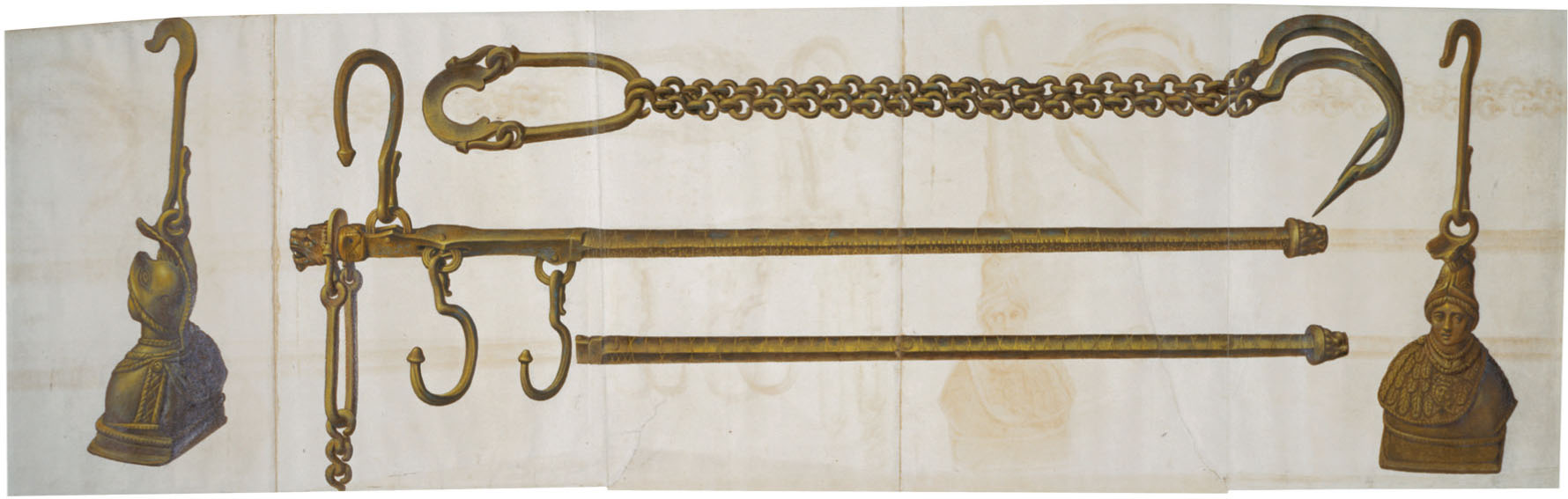

George’s coronation on 22 September 1761 – 14 days after his marriage to Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz – was an occasion of greater splendour than that of any of his immediate predecessors. It was followed by a magnificent banquet in Westminster Hall, three courses of a hundred dishes each, lit by 3,000 candles. At their table, admired as a ‘Triomfe of foliage and flowers’, the royal couple were served on silver-gilt plates. Since they had not eaten since early morning they devoured their food ‘like farmers’, as the poet Thomas Gray waspishly commented. This occasion is commemorated in the Royal Collection by the great ‘coronation service’ ordered by George III in 1761–2 (fig.157). Incorporating 8 dozen plates, 72 serving dishes, 6 tureens and 16 candlesticks, it was the largest royal order of silver for decades. Most of it was made by the King’s Principal Goldsmith, Thomas Heming, the first working goldsmith to hold the post since the early seventeenth century. He had been appointed in 1760 at the suggestion of Lord Bute, one of his most loyal patrons.

Shortly after the coronation George received his spectacular new state coach, an extraordinary synthesis of the arts (fig.158). Designed by the architect William Chambers (1723–96) in collaboration with the sculptor Joseph Wilton (1722–1803), it incorporates allegorical painted panels by the Florentine artist Giovanni Cipriani (1727–85). At the front are tritons blowing conch shells, announcing the appearance of the King as though he were Neptune, ruler of the seas, riding in his chariot. Delivered in time for the state opening of parliament in 1762, it is George III’s most instantly recognisable legacy to the image of the British monarchy.

Within a short time of their marriage George and Charlotte had become deeply attached to each other, helped by the rapid arrival of a large family and the King’s strong sense of personal morality – it was unthinkable that he might have had a mistress. The royal couple followed the precedent Frederick and Augusta had set in commissioning group family portraits. With George and Charlotte such celebrations of domestic harmony became a significant part of the iconography of the monarchy, for the first time since the reign of Charles I. It was appropriate, therefore, that the earliest large-scale family portrait commissioned by George III (or perhaps Charlotte) was a tribute to Charles I and Van Dyck (fig.159). It was painted in 1770 by a German artist, Johan Joseph Zoffany (1733–1810), who had settled in London in 1760, and was recommended to the King by Bute. The family are all in ‘Van Dyck’ dress, a popular style choice for masquerades since the 1740s but chosen here for its dynastic resonance. The painting looks back to the ‘Great Peece’ of Charles I and Henrietta Maria with their children (see fig.59), and the pose of the two eldest princes, George and Frederick, is modelled on another Van Dyck portrait in the Royal Collection, that of the 1st Duke of Buckingham’s sons, George and Francis Villiers.

Zoffany’s painting quickly became well known: it was exhibited at the Royal Academy and an engraving of it was issued almost at once. The engraving was the basis of a further reproduction in the form of three porcelain groups, made in about 1773 by ‘Mr Duesbury’s Derby and Chelsea Manufactory of Porcelain’ (fig.160). This was William Duesbury (1725–86), owner of the Derby Porcelain Works, who, having bought the Chelsea factory, opened a new warehouse in Covent Garden in 1774. His models, designed to promote the new company, are today exceptionally rare, and so are unlikely to have circulated widely, but their creation links the royal family with an important aspect of national life, the encouragement of British manufacturers.

At the outset of his reign it seemed possible that George III’s interest in Charles I would go beyond Van Dyck portraits and dress to encompass art collecting on a scale that no British monarch had contemplated since the seventeenth century. In 1762 the King bought, for £20,000, the collection of paintings, drawings, books, coins, gems and medals formed by Joseph Smith (c.1674–1770), the British consul in Venice. It was the largest single purchase of works of art for the Royal Collection since the Gonzaga acquisition 130 years before. The collection is famous for its works by eighteenth-century Venetian artists, and in particular an incomparable group of paintings and drawings by Canaletto (1697–1768), but it seems likely that it was Smith’s books that first attracted George.

The old royal library, which went back to the time of Edward IV and was formerly housed at St James’s Palace, had been given to the British Museum by George II in 1757. Even before his accession, George had developed an interest in books, encouraged by Bute, who was a great bibliophile, and the idea of creating a new Royal Library seems to have taken shape soon after his grandfather’s sale of the old one. Smith’s outstanding collection of early printed books was well known thanks to his publication of a catalogue of it in 1755, which Bute probably drew to George’s attention. An early overture to Smith about a possible purchase was forestalled in 1756 by the outbreak of the Seven Years War, a conflict that badly affected Smith’s finances and made him willing to contemplate the sale of his art collection as well as his books. Negotiations were reopened soon after the King’s accession by Bute’s brother, James Stuart Mackenzie, who was British envoy to Turin in 1758–61. By December 1762 the purchase of ‘the finest Collection in Europe’ was being reported enthusiastically by the London press.

If a full inventory was made of Smith’s paintings and drawings at the time of the purchase it has not survived, and it is not clear whether the King bought all Smith’s paintings or only a selection. Around a quarter were Italian Old Masters, but almost nothing is known about how Smith acquired them, although some may have come from the collection of the last Duke of Mantua, sold in Venice in 1710. They were uneven in quality, but did include a handful of outstanding works, notably two panels by Giovanni Bellini (c.1430–1516), his last surviving portrait (fig.161) and the Agony in the Garden. The King seems to have given the latter away, since it was sold from Joshua Reynolds’s collection after his death, and is now in the National Gallery, London.

Smith also owned a significant group of works by northern painters. Some were probably obtained through trading contacts in Amsterdam, but others were bought by him in 1741 as part of the collection formed by Giovanni Pellegrini, who had worked in The Hague. These paintings included Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman by Johannes Vermeer (1632–75; fig.162). Although now one of the most admired works in the Royal Collection, it was not singled out for special praise in the eighteenth century, when (thanks to a misreading of the signature) it was attributed to Frans van Mieris the Elder (1635–81).

Consul Smith’s work as a banker had led him into picture dealing, the origin of his huge collection by contemporary Venetian painters, of which 162 can be identified in the Royal Collection today. In the 1720s Smith had begun to acquire and commission works by Sebastiano Ricci (1659–1734) and his nephew Marco Ricci (1676–1730); Smith eventually owned over 200 drawings by Ricci, some for paintings that he had commissioned. Between 1711 and 1716 the Riccis were in London, where they designed sets for theatres and opera houses. This may have led to an introduction to Smith, who was married to the leading English prima donna Catherine Tofts. The 26 paintings by Sebastiano in the Royal Collection (fig.163), eight of which were painted jointly with Marco Ricci, demonstrate why he was celebrated as the heir to Paolo Veronese (1528–88).

Smith also owned classical landscapes by Francesco Zuccarelli (1702–88) and paintings of architectural subjects, including English Palladian buildings, by Antonio Visentini (1688–1782), who worked for Smith in many capacities, as engraver and illustrator as well as architect. Other leading Venetian artists are more patchily represented in the purchase, but this may in part be a result of dispersals after the collection arrived in England. For example, an early nineteenth-century inventory of the Italian pictures in the Royal Collection lists seven religious paintings by Giovanni Battista Piazzetta (1682–1754), but the only works by him in the collection today are 36 drawings of heads in black-and-white chalk (fig.164). Some are portraits (including self-portraits) but most are anonymous studies, drawn with great subtlety, but elusive in mood. They were greatly admired, to judge from the copies made of them by George III’s daughters as exercises in drawing.

Piazzetta never attracted much attention from English collectors but that was not the case with the most famous female Venetian artist, Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757), whose works, especially in pastel, were eagerly sought throughout Europe well before Smith met her. Acting as her agent, he also acquired a large body of her works, but only five of the 38 purchased by the King are now in the Royal Collection. As well as a self-portrait, they include a painting that became famous when it was in Smith’s collection, A Personification of Winter (fig.165). Described at the time of the sale as ‘a Beautiful Female covering herself with a Pelisse allowed to be the most excellent this Virtuosa ever painted’, it was a personification of the season that substituted a seductive young woman for the customary elderly man. George III hung in it his bedroom.

Smith owned the greatest collection ever formed of works by Canaletto, of which 50 paintings, 143 drawings and 46 etchings are in the Royal Collection. The fact that this is by far the largest group of his works in existence perhaps helps to explain why his reputation is much higher in Britain than in his native land. One factor in Canaletto’s success with British collectors was his relationship with Smith. From the outset of his career in the 1720s, Canaletto suffered from a reputation for over-charging and long delays in delivering. By 1730 Smith had taken charge of his practice, agreeing prices and organising framing and transportation. He also bought and commissioned works for himself, including a set of six large views of the Piazza and Piazzetta San Marco at different times of the day that are among the painter’s finest early works (fig.166). Smith further promoted Canaletto by publishing in 1735 a set of engravings of views of the Grand Canal, based on 14 paintings that are all now in the Royal Collection. When the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1740 interrupted the flow of potential clients to Venice, he encouraged Canaletto to diversify into views on the Brenta Canal, antiquities of Rome and architectural capriccios. Bearing a letter of introduction from Smith, Canaletto moved to England in 1746, where he worked on and off for the next nine years. He brought back with him to Venice paintings and drawings of London, some of which were acquired by Smith (fig.167). Canaletto’s work fell out of fashion around the middle of the century in favour of younger rivals such as Francesco Guardi (1712–93), whom Smith – perhaps out of loyalty to his old friend – did not collect.

Given the international fame of the Royal Collection’s Old Master drawings, it is surprising how quickly the collection was put together. With the exception of the drawings believed to have been acquired by Charles II, and Frederick, Prince of Wales’s Poussin drawings, most of its highlights were bought by George III within a decade of his accession. The agent who travelled the continent in search of them was the King’s Librarian, Richard Dalton (c.1715–91), since drawings, like prints, coins and medals, were by tradition part of a library collection. Like many art dealers and agents in the eighteenth century, Dalton had begun as a painter, and several of the red chalk drawings of sculpture he made while in Rome in the early 1740s are in the Royal Collection. His wide knowledge of European art collections was put to good use on a tour of Italy in 1758–9, when he acquired some 700 drawings for Prince George, including 40 from the grandson of the painter whom Charles I had tried in vain to tempt to England, Guercino (fig.168). He also inspected the celebrated collection of Cardinal Alessandro Albani in Rome, which, with that of Consul Smith (also visited by Dalton), was to be acquired by George once his financial resources had been transformed by his accession.

Dalton had not been impressed by the Albani collection, almost certainly because he was not shown all of it, but the King and Lord Bute were encouraged to pursue the idea of acquiring it by Robert Adam (1728–92), who in 1761 was appointed Joint Architect of the King’s Works. Adam had studied the collection while he was in Rome in the 1750s, and the secret negotiations for its purchase were handled by his younger brother, James. A price of £3,500 for 200 albums of drawings and prints was eventually agreed, largely because the cardinal’s mistress, the Contessa Ceroffini, wanted the money for a dowry for her eldest daughter. The collection, some of which had been inherited from Albani’s uncle Pope Clement XI, was a magnificent representation of largely seventeenth-century draughtsmanship by such artists as Bernini, Domenichino (1581–1641), the Carracci, Carlo Maratti (1625–1713) and Carlo Fontana (1634/8–1714).

The purchase also included thousands of sheets from the ‘paper museum’ of the collector and antiquary Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588–1657), which Albani had bought in 1714 (fig.169). This unique visual encyclopaedia of contemporary knowledge consists of detailed drawings and watercolours of classical antiquities, archaeological finds and geological and natural-history specimens, supplemented by prints on topography, portraiture, costume, ceremonies and military matters. Although intended for publication, the accumulation of drawings soon outran such an idea, which was not revived until the twenty-first century, when the Royal Collection and other owners of sheets from the ‘paper museum’ initiated a multi-volume catalogue of this extraordinary seventeenth-century database.

Among the highlights of George III’s acquisitions of Old Master drawings are groups by Raphael and Michelangelo. Dalton described one of the drawings he sent back from Italy in 1758 as a ‘Rafaele’, but it cannot now be identified. The first Raphael drawing known to have been acquired by the King was part of the Consul Smith purchase, Christ’s Charge to Peter (fig.170), an appropriate acquisition since it is a working drawing for one of the ‘Acts of the Apostles’ tapestries, of which the cartoons are in the Royal Collection. The origins of other sheets by Raphael in the collection are mysterious: like so many of the Old Master drawings, there is no record of them in royal ownership until they appear in an inventory drawn up in 1810. Among those listed then for the first time are some of the Collection’s famous group of highly finished drawings made by Michelangelo as gifts (fig.171). Given that these were recognised from the moment of their creation as some of the greatest drawings ever made, and were much copied, it is puzzling that their whereabouts in the eighteenth century are unknown, although their immaculate condition suggests that they were well looked after.

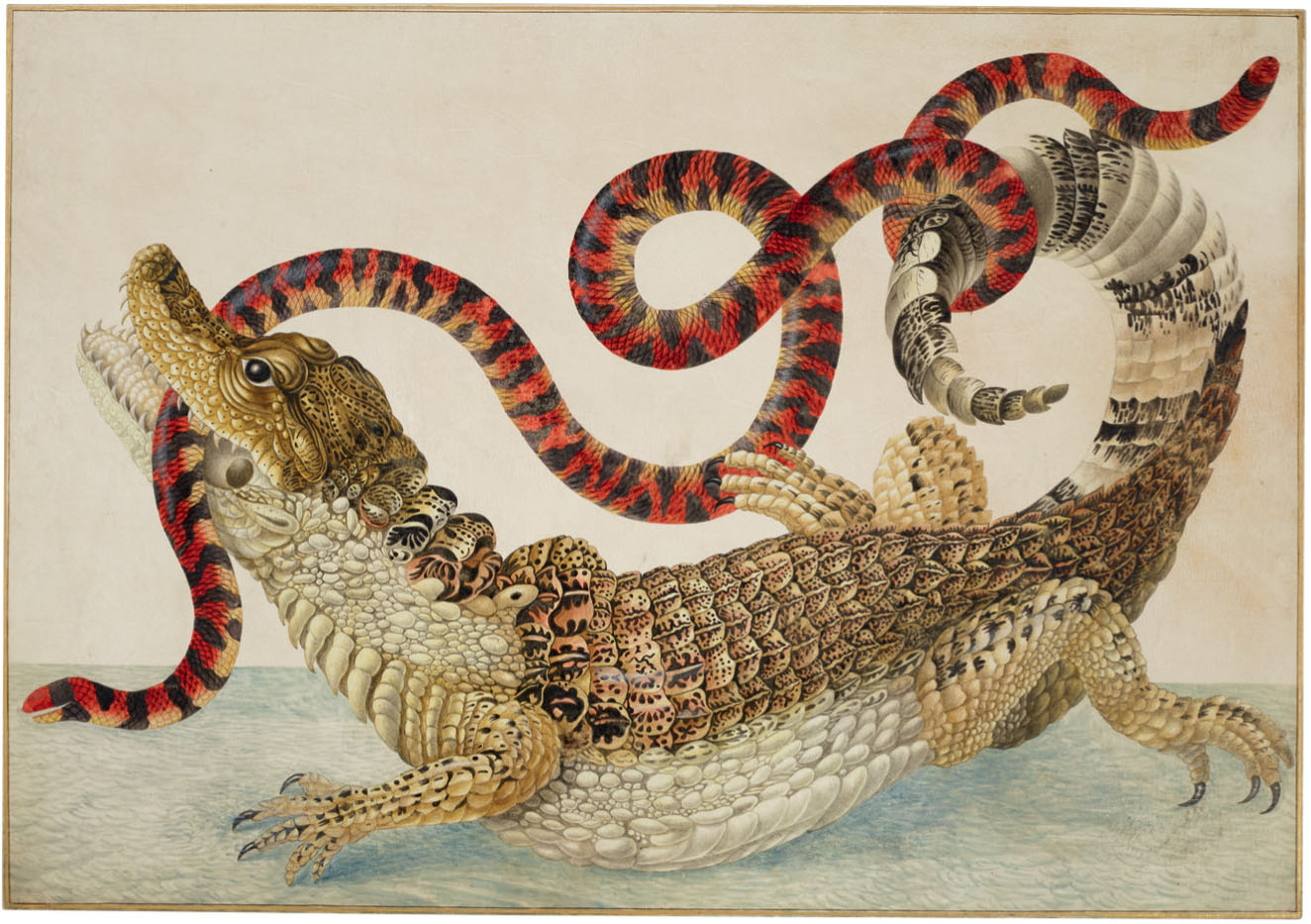

Having acquired drawings and other works of art at a high level for the first few years of his reign the King’s interest in such collecting flagged and was never to revive with any intensity. Some of the reason for that was practical, as he and the Queen had satisfied their immediate need for pictures to furnish their houses. He also focused his attentions, and budget, on book collecting. In addition, his relationship with the man who had done so much to encourage his interest in art came to an end in 1763 when Lord Bute decided to retire from public life. Yet, despite the evident pleasure the King got from many of his paintings, it might be doubted whether he ever thought of himself as a connoisseur in the mould of Bute; for him, art was just one aspect of the wide-ranging intellectual interests that made George III a monarch of the Enlightenment. It can be argued that his interest in drawings, for example, was practical rather than aesthetic. Left to himself, he acquired them largely for their subject matter. In 1755, when George was only 16, he bought at auction 95 drawings and coloured engravings by a pioneer of the science of ecology, the outstanding illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), which included studies of insects and reptiles in Suriname, South America (fig.172). One of the King’s last big acquisitions of drawings was of 263 watercolours made by Mark Catesby (1682/3–1749) for his Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1729–47), which were bought in 1768.

However, the development of his collections of atlases and maps led to the King accumulating enormous groups of drawings and watercolours of topographical, naval and military subjects, of which only the last survives in the Royal Collection (the others are now in the British Library). Designed to extend the King’s knowledge of his country, its developing empire, and military and naval activities, these collections were not created for aesthetic reasons. Nonetheless, they include outstanding works by such topographical artists as Thomas Sandby (1721–98) and his brother Paul (1731–1809) that help compensate for the fact that the King showed no interest in the achievements of British watercolour artists that are such a highlight of the latter part of his reign.

In 1762 the King purchased Buckingham House as a gift for his wife. Built in 1702–5 for John Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham and Normanby, with a splendid position overlooking St James’s Park, the house was, the King told Bute, ‘not meant for a palace, but a retreat’, and was habitually referred to as ‘the Queen’s House’. George oversaw the alterations to Buckingham House with Sir William Chambers, who for half a century was the King’s closest adviser in architectural matters. George took a great deal of care in arranging the paintings in the house. The entrance hall, for example, was hung with Canalettos and Zuccarellis; the prominence given to these works bought from Consul Smith suggests that one motive for that purchase had been to furnish the house. The new paintings were supplemented by works from his father’s collection, and the Queen’s Saloon was hung with the Raphael cartoons. Their move from Hampton Court provoked criticism, because public access to them was now much more limited.

Since the house was enlarged and remodelled beyond recognition when George IV converted it into Buckingham Palace in the 1820s, our knowledge of the interiors created by George and Charlotte is based on paintings. The earliest is an enchanting portrait by Johan Zoffany of the Queen, aged about 21, with her two eldest sons, George, later George IV, and Frederick, later Duke of York (fig.173). The setting is one of the ground-floor rooms at Buckingham House, which had been specially arranged with some of the Queen’s possessions for the purpose, since her rooms were in fact on the first floor. Zoffany may perhaps have chosen the setting so that he could include a view out into the garden, where a solitary flamingo is taking a stroll. Whereas the King preferred to live austerely, without carpets – he was English in his belief that there was something virtuous about physical discomfort – the Queen’s rooms were furnished luxuriously. Zoffany has depicted in the background a superb French longcase clock by the eminent French horologist Ferdinand Berthoud (who was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society at about the time Zoffany was painting the picture). The clock’s magnificent marquetry case, lavishly mounted in ormolu, is the work of a leading cabinetmaker, Charles Cressent (1685–1768; fig.174). The Queen had a taste for richly decorated furniture to judge from her jewel cabinet, made in 1762 (fig.175). This is a masterpiece by William Vile (c.1700–67), who, with his partner John Cobb, was appointed by the King ‘Joint Upholsterer in Ordinary’ in 1761 but retired only two years later, possibly because of ill health. He was succeeded by John Bradburn, who had trained with Vile and Cobb.

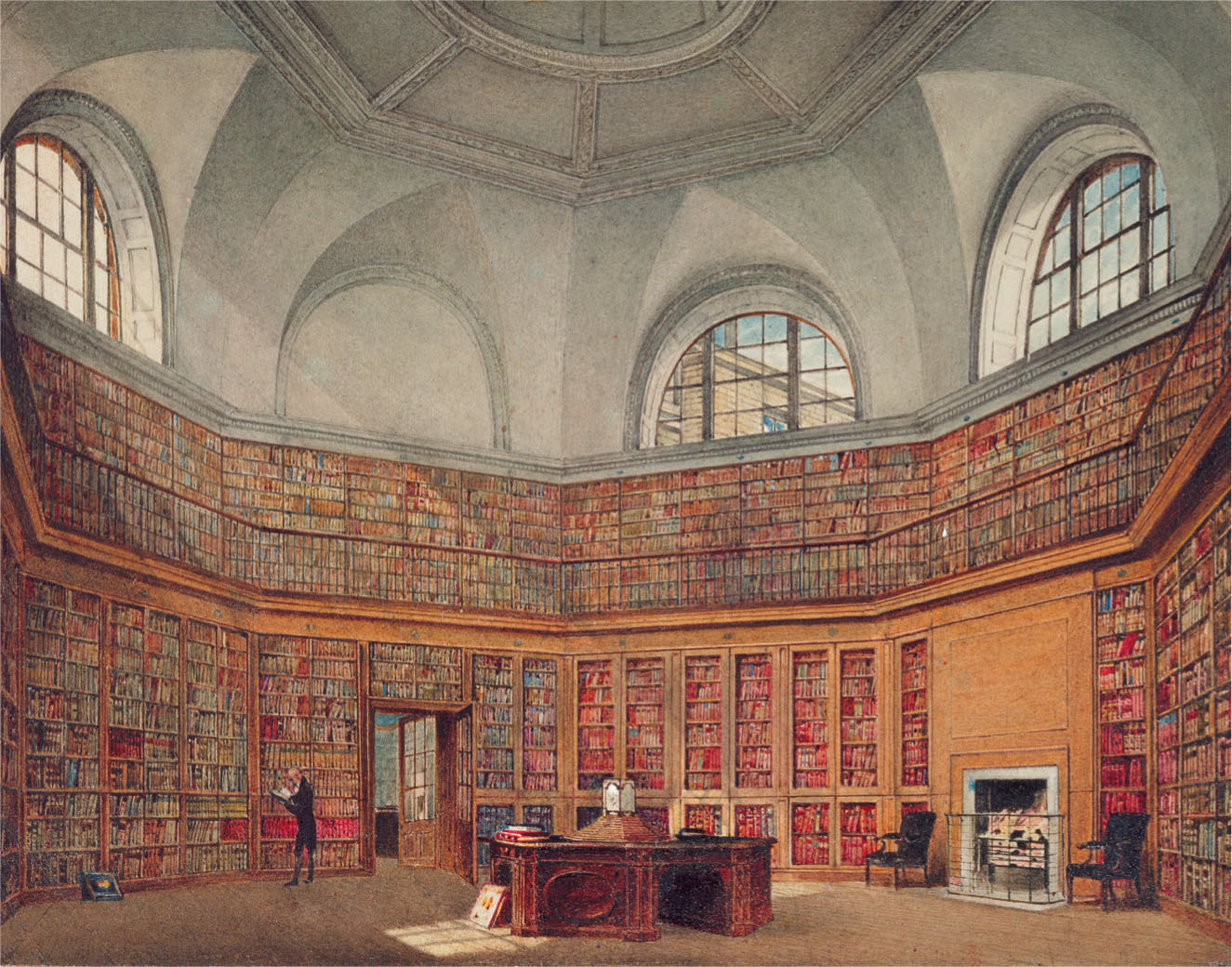

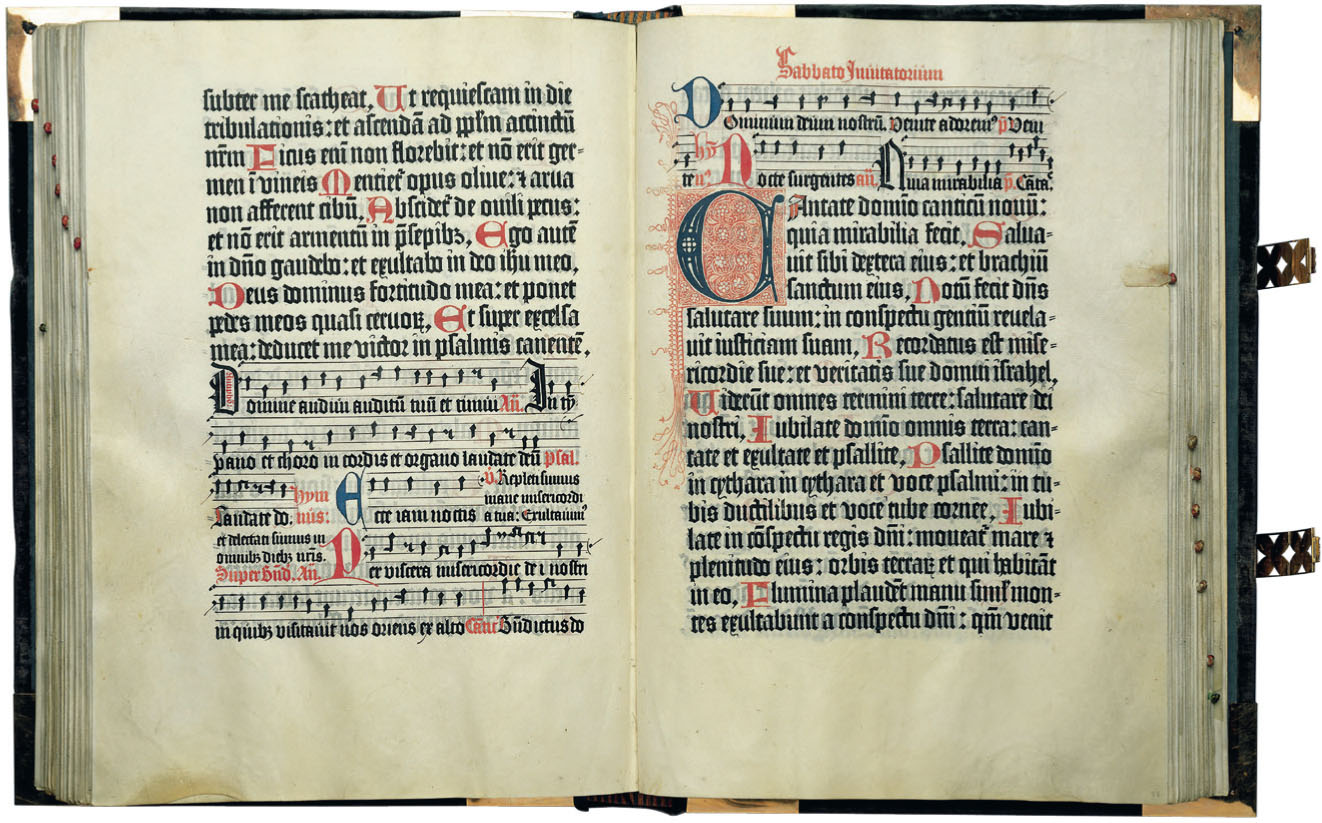

Although bought for the Queen, Buckingham House was also a favourite of her husband. This was partly because it gave him space to pursue his consuming interest in books, which, under the guidance of Frederick Augusta Barnard (1743–1830), who replaced Dalton as King’s Librarian in 1774, was developed in a systematic way. By the time of the King’s death in 1820, the library contained around 65,000 printed books and 19,000 pamphlets. There were also manuscripts, as well as the bound volumes of maps and topographical views. The King first kept his books in the Old Palace at Kew, but following the arrival of Consul Smith’s library, they were moved to a room added to Buckingham House by William Chambers in 1762–4. Between 1766 and 1773 three large rooms were added, of which the most impressive was the Octagon Library (fig.176), below which was the King’s bindery, in operation from 1780. The King seems always to have intended that the library would have a public function – it was generally open to scholars – as George IV’s gift of his father’s books to the nation in 1823 acknowledged. Some items of particular interest were retained (together with all the King’s books in his other residences). Among them is an extraordinary rarity, one of only ten surviving copies of the second book (after the Gutenberg Bible) to be printed by moveable metal type, the psalter issued in Mainz in 1457 (fig.177).

The library contained other collections, and in 1774 the height of one of the rooms was raised to accommodate a gallery for the King’s models of ships and seaports. At the centre of the Octagon Library was an octagonal desk crowned by an astronomical clock made by Eardley Norton in 1765 for which the King paid £1,042, which presumably included its very fine mahogany case (fig.178). George had a passion for horology and he delighted in taking apart and reassembling the workings of his vast collection of clocks. They were complemented by his superb scientific instruments, now owned by King’s College, London, which are on loan to the Science Museum.

Among the manuscripts in the library was the collection that George Frideric Handel had bequeathed to John Christopher Smith, one of his favourite pupils, and later his manager and principal copyist. Aware of the King’s great admiration for the composer, Smith’s son (who had been Princess Augusta’s music teacher) gave the music manuscripts to the Royal Library in about 1773, together with a harpsichord and small house organ. It seems likely that the gift also included a marble bust of Handel by Louis-François Roubiliac believed to have been given to Smith’s father by the composer (fig.179). The bust is first recorded in the King’s Apartments at Buckingham House in 1783, the year before the 25th anniversary of the composer’s death was marked by the great Handel Commemoration in Westminster Abbey, which the King had encouraged. The Handel manuscripts remained in the Royal Library until 1957, when they were presented by Queen Elizabeth II to the nation, and are now in the British Library.

This was not the only bust of Handel that George III owned; he placed another, also attributed to Roubiliac, on top of the organ in Queen Charlotte’s Breakfast Room at Buckingham House. This makes it additionally surprising that sculpture, ubiquitous in eighteenth-century libraries, was absent from the King’s. Perhaps the fact that George was unable to go on the Grand Tour explains why he took such little interest in sculpture, although that had not stopped his grandmother furnishing her library with busts or his mother commissioning sculptures by Joseph Wilton of Minerva and the Muses for her gardens at Kew. Queen Charlotte did not acquire sculpture either, but her curiosity about the works that travellers so much admired in Italy prompted a remarkable commission. In 1772 she gave Zoffany £300 to visit Florence and make a painting of the works of art in the famous Tribuna, the octagonal gallery in the Uffizi that contained the cream of the Medici collections in paintings as well as antique sculpture (fig.180).

It was not a happy job. In the first place, Zoffany took seven years to complete the painting, not returning to London until 1779. He had to devise a very complex composition, and get permission to move into the Tribuna famous works hung elsewhere. He also exceeded his brief by including portraits of many celebrated connoisseurs, diplomats and visitors to Florence. The Queen, who had wanted something of a more purely documentary nature, was not pleased by the inclusion of portraits of people she had never heard of, and the King was probably aware of the sexual proclivities of the men admiring the bosoms and buttocks on display. In any case, the painting did not suit the strait-laced nature of their court. Zoffany was not employed by the King or Queen again and had to fight to be paid for a painting that has embodied the concept of the Grand Tour ever since.

In December 1768 George III made one of his best-known contributions to national life by approving the Instrument of Foundation of the Royal Academy, which was to be both a school of art and design, and a body that would mount annual exhibitions. In so doing, he realised a long-held ambition of his father. The King provided practical help by arranging for the Academy to be accommodated in old Somerset House, and it was to remain in the building that replaced it until 1837. George was well informed about the the new organisation, since William Chambers was one of its creators and founding members and in 1769 Zoffany (who had yet to fall from favour) was nominated as member by the King. It was hoped that the Academy would both foster a national school of art and encourage public appreciation of painting, sculpture and architecture, based on accepted canons of taste.

Among the ambitions of the new organisation was the promotion of ‘history painting’: the depiction of scenes from history, the Bible or classical legend. Although traditionally regarded as the most important genre in painting, it had never found many patrons in Britain. Encouraged by the debates that led to the foundation of the Royal Academy, the King decided to set a lead. His chosen artist was Benjamin West (1738–1820), born in Pennsylvania and trained in Italy, who moved to England in 1763. When in 1768 the King saw West’s Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus (1768; now in Yale University Art Gallery), he asked him to paint the departure of Regulus from Rome (fig.181). After its completion, in 1769 – in time to be shown at the first Royal Academy exhibition – the King commissioned a pendant depicting the oath of Hannibal. The eventual result was a series of six paintings, completed in 1773, hung together in one room at Buckingham House with a replica of West’s celebrated Death of Wolfe (1771). One of the high points of European neoclassical painting – although rarely recognised as such in Britain – West’s canvases owe an evident debt to the Raphael cartoons. Described from 1772 as ‘Historical Painter to the King’, West gave drawing lessons to the Queen and princesses. In 1791 he was appointed Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and in 1792 he became President of the Royal Academy. West painted more than 60 works for the King and Queen, including two sets of paintings for Windsor Castle, eight scenes from the reign of Edward III for the Audience Chamber and 36 religious subjects for a new Royal Chapel, of which only the former remain in the Royal Collection (the chapel was never built).

Although he was an accomplished portrait painter, West never monopolised royal portraiture in the way that he did history paintings. Before his accession, George sat to Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), but showed no inclination to offer him commissions thereafter, largely because he preferred Allan Ramsay, but also because it seems that he never warmed to Reynolds as a person. Nonetheless, in 1769 he knighted him, in acknowledgement of Reynolds’s position as President of the Royal Academy, and in 1784 appointed him Principal Painter, following Ramsay’s death. Knowing that he was never going to be a favourite, Reynolds described the post as ‘near equal in dignity with his Majesty’s rat catcher’. By then Thomas Gainsborough (1727–88) had established himself at court with two glamorous full-length portraits of the King and Queen that were enthusiastically received when exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1781 (fig.182). Charming, witty, and lacking Reynolds’s rather ponderously intellectual approach to painting, Gainsborough knew exactly how to flatter his royal sitters.

The King’s desire to encourage British painting was in part an extension of his wish to promote the country’s manufacturers. As far as luxury goods were concerned, France was the main rival, although neither George nor Charlotte ventured to set up royal manufactories like Sèvres or Savonnerie. Instead they sought to offer encouragement through commissions or by public demonstrations of royal interest, such as a visit to the Worcester china factory in 1788. For the King it probably did not matter greatly what a firm was making, but Charlotte’s interest in the decorative arts made her responsive to British makers of luxury items hoping to win royal approval. In 1770 the Birmingham entrepreneur Matthew Boulton (1728–1809) was given a three-hour audience by the King and Queen. His successful factory made small items in metal such as buckles and he now wanted to discuss his latest venture, the manufacture of ormolu, or gilded bronze, used in particular for decorative mounts on vases and furniture, where French supremacy seemed untouchable. As a result, an order was placed for a chimney garniture of Derbyshire blue john vases to be mounted in Boulton’s ormolu, which the Queen placed in her bedroom at Buckingham House (fig.183). The vases were part of a group of pieces made for the royal family by Boulton that included a clock designed by William Chambers that was marketed (without authority) as ‘The King’s Clock’. These exceptionally refined items have always been greatly admired and so it is sometimes forgotten that in commercial terms Boulton’s ormolu was a flop, and he made very little after 1771.

British manufacturers of ceramics mounted a more successful challenge to French dominance. In 1763 the King and Queen commissioned the Chelsea factory to supply a porcelain dinner service as a gift for the Queen’s eldest brother, Adolphus Frederick IV, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (fig.184). The factory was then being run by Nicholas Sprimont, who had supplied silver for the King’s father, and the Rococo forms of the Mecklenburg service would probably have appealed to Frederick. The service was recognised as a technical breakthrough thanks to its blue enamel, known as ‘Mazarin blue’, which matched in brilliance the dark blue enamels that Sèvres had made fashionable. Since the service left England immediately after its creation, it helped to advertise British porcelain abroad: the traveller Thomas Nugent thought it ‘rich and beautiful beyond expression’ when he saw it in the ducal palace at Neustrelitz in October 1766.

It was, however, England’s simple wares that were most envied abroad, and in particular the creamware manufactured by Josiah Wedgwood (1730–95) in Staffordshire. Invented in the 1740s, creamware is a cream-coloured, lead-glazed refined earthenware that, by the end of the century, had displaced traditional tin-glazed earthenwares such as Delft. This change in taste was largely due to the commercial genius of Wedgwood, who used royal approval to promote his wares to a wide market through what would now be called branding. In 1765, the year that Wedgwood opened his first London showroom, the Queen commissioned a tea service in green and gold creamware. In the following year he was officially appointed Potter to Her Majesty and was permitted to rename his creamware ‘Queen’s ware’. The Queen bought Wedgwood wares, but this was no comparison with the 1773 ‘Frog service’ of 952 pieces ordered by Catherine the Great in 1773, which Charlotte personally inspected in Wedgwood’s showroom before it was sent to Russia.

Almost none of Charlotte’s Wedgwood can now be identified in the Royal Collection, which retains very few of her commissions and purchases. This was because, after her death, the majority of her possessions were either divided between her four youngest daughters, the princesses Augusta, Elizabeth, Mary and Sophia, or sold at auction to pay the Queen’s substantial debts. Portraits apart, Charlotte would, therefore, be a largely invisible presence in the Royal Collection were it not for the survival of her private retreat on the Windsor estate, Frogmore. Bequeathed to Princess Augusta, the house remains the property of the Crown, and the decision in the 1980s that it should be restored and shown to the public opened a window into Charlotte’s private world.

The acquisition of Frogmore was prompted by the unexpected revival of royal interest in Windsor Castle, which, with the exception of occasional visits for hunting or Garter ceremonies, had been neglected since the death of Queen Anne. Its long years of picturesque slumber are evocatively recorded in watercolours and drawings of the Castle and its environs by the Sandby brothers. Thomas Sandby, who from 1764 acted as deputy ranger of Windsor, collaborated with his brother Paul on a series of engraved views of the park and in the 1760s Paul made a series of views of the Castle that are among the high points of English watercolour painting (fig.185). Following the King’s decision in 1776 to make greater use of Windsor, the royal family moved into buildings erected by Queen Anne on the South Terrace, the Castle having been judged uninhabitable. By degrees it was refurbished but was not fully occupied by the court until 1804.

Charlotte found the Castle cold and uncomfortable, as well as too public, so she often retreated to Frogmore during the day. A modest Trianon to the Versailles of Windsor, just a mile to the north, the house was probably designed by Hugh May, architect of the remodelling of Windsor Castle for Charles II. Having purchased the lease in 1792, Charlotte commissioned the architect James Wyatt (1746–1813) to remodel and enlarge the building, and, once she had acquired some more land, laid out a landscape garden. This was always the central attraction at Frogmore, as it was here that Charlotte and her daughters could pursue their enthusiasm for horticulture and botany. ‘I’ve been spending the mornings in the company of my daughters at Frogmore, my little Earthly Paradise’, wrote the Queen to her brother Prince Karl in 1802, ‘amusing ourselves with a good read, working around a large table in the garden under the shade of some beautiful trees, and marvelling that the time goes by much more quickly than we would have wished’. This atmosphere of studious pleasure is well captured by Charles Wild’s watercolour of the library at Frogmore, flooded by light from large windows looking into the garden (fig.186).

One of the rooms added by Wyatt was decorated to simulate a conservatory open to the sky, with flowers painted directly on the walls as well as large inset paintings that depict cascading blooms (fig.188). These are the work of Mary Moser (1744–1819), who, with Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807), was one of the two female founder members of the Royal Academy of Arts. Moser also provided patterns for floral embroidery and gave drawing lessons to the princesses. Perhaps the most talented was Princess Elizabeth (1770–1840), who was to marry the Prince of Hesse-Homburg. Examples of her silhouette pictures and floral paintings for furniture are preserved at Frogmore; her proud father arranged for some of her pictures to be published as engravings. After the eldest daughter, Charlotte (1766–1828), married the Duke (later King) of Württemberg in 1797, she applied her artistic skills to decorating porcelain blanks made in the ducal factory at Ludwigsburg that she then fired in her own kiln (fig.187). In 1805 she wrote to her father that she would ‘venture to bespeak some flower pots after my design which I hope your Majesty will place in your palace’.

There was a dark shadow that made the Queen’s ‘Earthly Paradise’ all the more precious to her. In the autumn of 1788 the King’s mental health collapsed. Although the episode lasted only a few months, he suffered severe recurrences in 1801, 1803 and 1810, whereupon a regency was declared. The King’s health never subsequently recovered, prompting much speculation ever since about the cause of his illness. Whether it was the metabolic disorder porphyria, or an acute mania, may never be known; in any case, his doctors and family were helpless.

This family tragedy struck at a time when the monarchy was beginning to embody not just a nation but also a global empire. By the time of the King’s last bout of illness, Britain had recovered from the loss of the American colonies in 1776 and had defeated French imperial ambitions. These successes began to have an impact on the Royal Collection: for example, at the time of her death, Queen Charlotte owned 50 items of ivory furniture and boxes made in India. Other treasures came as booty. Determination to prevent the French forming an alliance with Tipu, Sultan of Mysore, led to war, which culminated in his death in 1799. After British troops captured his citadel, Seringapatam, Tipu’s treasury and library were ransacked, and the gold coverings of his throne were cut up for distribution to the troops. Above the throne canopy was a huma or bird of paradise, made of gold and studded with gems (fig.190). This was obtained by the Governor-General of India, Lord Wellesley, who presented it to George III. It was explained at the time that the huma ‘is looked upon as a Bird of happy Omen, and that every Head it overshadows will in time wear a Crown’.

An even rarer treasure of Indian art was acquired by the King as a gift. In about 1798 the Nawab of Oudh offered Wellesley’s predecessor as Governor-General, Lord Teignmouth, six manuscripts from his library at Lucknow. Recognising that their superlative quality made them fit only for ‘a royal library’, Teignmouth declined the offer but suggested that the Nawab might give them instead to the King. Among them was the Padshahnama (or Chronicle of the King of the World), a unique official description of part of the 30-year reign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (1592–1666). Its 44 illustrations, by 14 court painters, include some of the finest Mughal paintings in existence (fig.189). Dating from 1630–57, they depict all the leading figures of Shah Jahan’s court, a centre of artistic and architectural achievement that produced such monuments as the Red Fort at Delhi and the Taj Mahal at Agra.

As the British world of empire expanded, the King’s contracted. By the end of his life he was no longer able to enjoy the library that he had spent so much of his life assembling. In the last decade of his life he became deaf and blind and was confined to Windsor Castle, only intermittently lucid. His last pleasure was playing the harpsichord that had belonged to Handel, telling his attendants that the music he hammered out was a favourite piece of ‘the late King’. His appearance in these final years is recorded in one of the most poignant of all royal portraits, a miniature on enamel by Joseph Lee, derived from a sketch made by the sculptor Matthew Wyatt when he was working at Windsor (fig.191). Although, at George IV’s request, the composition was reworked to emphasise his father’s royal status, the contrast with Ramsay’s coronation portrait is painful to contemplate. By now the spotlight had shifted irrevocably to his heir. During George III’s 60-year reign, the Royal Collection had been enormously enriched, but the sad story of his last years prematurely brought to centre stage the son who was to transform it.