Chapter 5

Harvesting

There is great satisfaction to be had in harvesting healing plants of the best quality, knowing that they will regenerate for further harvests. Above all, a good herbal harvest is such a pleasure, as Robert Hart described in Forest Gardening back in 1991:

My living room is adorned with a herb-rack hanging from the ceiling and every autumn it is filled with aromatic herbs which are left throughout the winter to dry.... These drying herbs give a delicious and healthful atmosphere to the room.1

For our own satisfaction, we want to maximise active ingredients and the best quality. And, ideally, we want to preserve these wonderful medicinal plants well for later use. For these reasons it is important to have a good understanding of principles and practice involved in harvesting, drying and processing medicinal plant parts from roots to bark, flowers, fruit and leaves. This chapter covers sustainable harvesting on a small scale with pointers towards dealing with larger harvests having more commercial potential. Key aspects of planning seasonal harvesting arrangements are identified for bark, leaves, flowers, seeds and roots. Good practices for harvesting of cultivated medicinal plants are described, with subsequent drying and processing techniques. Storage matters are discussed, including the shelf life of preserved plant material. The importance of monitoring, labelling and recording outputs is emphasised. For further detail on harvesting of individual trees and shrubs you can also view the plant profiles in the Part 2 Directory.

Good harvesting practice

Harvesting right is critical to the whole process of producing quality materials from medicinal plants. Good harvesting is sustainable and ensures consideration of future years of supply. The highest quality of harvested products is essential for users and producers of medicinal plants, whether intended for domestic use or for commercial markets. Ideally, an end product is required that is the correct plant, the relevant part, with a maximum of active constituents, deriving from material without contamination or degradation, and obtained without ruining the environment or affecting biodiversity. Getting this right means applying some general principles to harvesting of medicinal plants whether in cultivation or in the wild:2

- Planning of harvesting

- Harvest should be carried out in appropriate conditions

- Clear instructions on safety and procedures for those harvesting

- Ensure accurate identification of plants

- Caring for the environment

- Minimise damage and contamination

- Ensure labelling of harvested material

- Keep records to allow traceability and monitoring.

Planning the harvest

Planning of harvests involves an estimation of timing, location, personnel and resources needed. Traditional approaches base the appropriate time for harvest on seasons when the best outcomes have been observed in practice (see table below). Bark harvests can be carried out all year round, though probably the best time for collecting bark with the maximum active ingredients is early spring, just before active growth is seen.3 Roots are thought to have most active ingredients in the dormant season, based on their stored materials. Many of the medicinally active ingredients in plants are secondary metabolites intended to protect from insect attack or to help limit damage. Thus leaves and ‘tops’ are usually thought to be at their best in spring shortly before flower buds open. Aromatic herbs, such as mint, appear to have their maximum content of essential oils in summer.4 The period for harvesting flowers may be limited since these can reach their best for a short period, sometimes just a matter of days. There are always exceptions, for example the leaves of the ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) are reputed to be highest in flavonoid active constituents just as they begin to yellow in the autumn. The level of active constituents in healing plants is surprisingly variable and research may not always provide conclusive advice. For example, isoflavonoids in a Chinese root herb were found to be most concentrated at the age of three years old if harvested in winter,5 but another investigation found that phenolic ingredients were highest during spring harvesting.6 Thus, different key constituents in medicinal plants can vary in their propor-tions throughout the year. More research is needed on the most appropriate periods for harvesting in order to maximise the most useful plant constituents.

Seasonal harvests

|

SPRING BARK AND BUDS Alder (Alnus glutinosa) Alder buckthorn (Frangula alnus) Birch (Betula pendula) buds and sap Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) buds Cherry (Prunus avium and P. padus) Cramp bark (Viburnum opulus) Prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum) Willow (Salix daphnoides and S. alba) |

SUMMER LEAVES AND FLOWERS Elder (Sambucus nigra) Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) Limeflower (Tilia species) Marigold (Calendula officinalis) Mint (Mentha species) Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) Nettle (Urtica dioica) Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) Rose (Rosa species) flowers St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) |

|

AUTUMN FRUITS AND SEEDS Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) Hops (Humulus lupulus) strobiles Prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum) berries Rose (Rosa canina) hips |

WINTER ROOTS Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) Elecampane (Inula helenium) Mallow (Althaea officinalis) Oregon grape (Berberis aquifolium) Paeony (Paeonia lactiflora) |

Appropriate conditions

Having the right conditions for harvesting medicinal plants helps to ensure that there is minimum deterioration before transport and further processing takes place. In general, dry and cool conditions are preferable for harvest. For any material harvested above ground, it is important to avoid wet conditions, as any moisture will contribute towards rapid deterioration. It is better to wait until conditions improve, but if there is no alternative then there must be a plan to dry the harvested materials effectively. Suitable equipment for harvesting includes sharpened tools (secateurs, loppers, pruning saw, spade), collecting bags (at Holt Wood we find that cotton pillowcases are excellent), pen and labels (string is useful to tie labels to bags). Health and safety precautions should be considered, with identification of any risks arising from harvesting, such as uneven ground, using sharp tools or felling tree branches.7 Depending on the conditions and site, collectors should wear long-sleeved shirts, thick trousers, hats, gloves and boots. The process of carrying out a risk assessment for an activity in the forest garden is covered in Chapter 3.

Rose hips are best harvested when red and ripe before they begin to wrinkle

Accurate identification of plants

In a cultivated environment, it is likely that plants are easily identified if an example is shown and this will help to avoid contamination with the wrong plants. Correct identity may be less easy to spot in a forest garden with diverse planting, and the situation may resemble wild-harvesting. It may be necessary to have on hand some botanically accurate plant descriptions to check the identity of specific plants.8 If harvest helpers are involved, then they need clear instructions about identification of the correct parts of plants to harvest, to avoid inappropriate material being harvested.9

Caring for the environment

Caring for the environment in a sustainable way during harvesting involves thinking ahead to the next harvest, thus ensuring that herbs, trees and shrubs are harvested in a way that allows ongoing production in the future. Some roots can be replaced in the ground to produce new plants; some flowers can be left to form seed. Any harvesting process needs to be considered in terms of disturbance and compaction to the soil which can impact on landscape and wildlife. Ideally there need to be paths of sufficient width to enable access. Use of light wheeled carriers such as a wheelbarrow may be appropriate to avoid repeated trips. Care is needed with removal of large branches or trunks by dragging away from the harvest site as these can also damage surrounding vegetation. Smaller branches and twigs can be bundled up for easier carrying.

Minimise damage and contamination

All harvested material should be inspected for dirt, insects and damaged parts. Flowers may need to be harvested by hand, looking out for insects and shaking them off. To enable further insects to escape, you can spread out flowers and leaves in a thin layer.10 Fruit must be harvested with care to avoid bruising so that there is less likelihood of deterioration. Roots are best harvested in drier soil conditions to reduce the amount of soil attached, then they can be washed in a bucket or tank of water. Harvesting bark is destructive for a tree if removed around the whole circumference of a tree trunk, and so it is preferable to harvest branches and peel these stems for bark. Many tree and shrub species will regrow from the base as a coppice crop, while others can be pollarded at 2 or 3m height to allow new growth of branches. Care should be taken to leave a clean stump since a damaged stump is likely to rot or die back.11

Ensure labelling and keep records

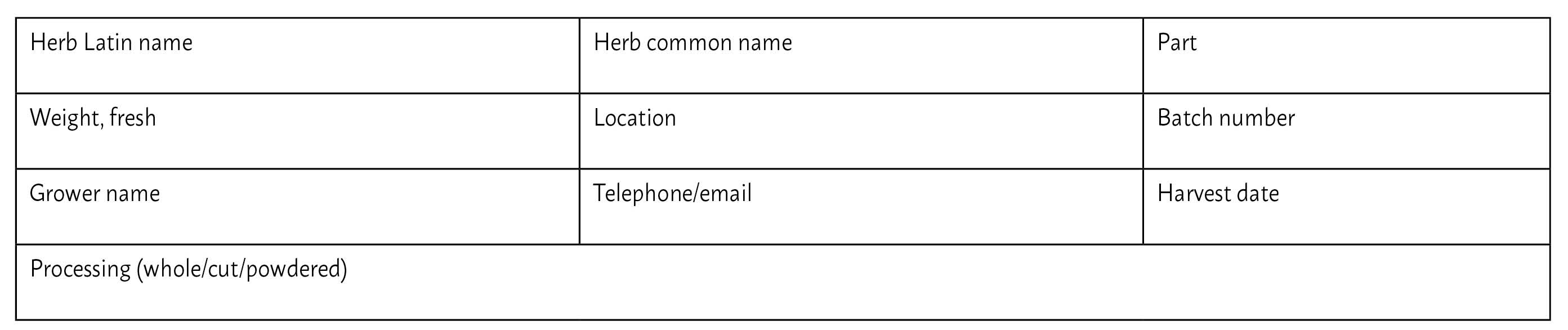

Labelling of the harvest is essential to avoid mixing up batches of plant material as they are moved through to drying, processing and on into storage. It is impossible to remember which plants are which, especially since they will look completely different once chopped up and dried. Labelling avoids waste too, as unidentified plant material cannot be used and, at best, has to be recycled as mulch. Use of both common and Latin names helps to ensure accuracy where there are similar plants being harvested. Other details include the part harvested and location with date of harvest. A label provides the basis for tracking a herb. Record-keeping of dates, locations, personnel and amounts of plants harvested is good practice (and essential for organic or other accreditation).

You may also want to keep plant samples in case of a need for future checks or responding to queries about provenance. Keeping a voucher specimen as a herbarium sample is a way to do this. Voucher specimens can be preserved using a plant press with boards, held together by screws. Typically, a whole plant is collected, or if large then representative parts of leaf and flower, slices of stem and bark. To complete the record, note the collector’s name, date, exact location, habitat type and additional details about the plant. The plant material is placed in the press, between blotting paper sheets, which is then placed under a weight or strapped tightly. The plant can be trimmed or rearranged after a few hours. The paper is changed frequently (daily) so that moisture does not allow degradation. The press can be kept in a warm well-ventilated area, and when fully dried the specimen is attached with glue dots or mounting tape to the herbarium sheet, leaving space for a label. Plant fragments such as seeds can be placed in an envelope and this is attached to the sheet.12 A well-made herbarium can keep indefinitely, providing an excellent record of actual plant source material.

Drying herbs

As soon as plant material is harvested it will start to deteriorate and drying to remove moisture is essential to prevent or reduce further decomposition. The moisture content of living trees and shrubs averages around 70% with a lesser proportion in woody parts. Effective drying reduces moisture content to maintain the quality and quantity of important healing constituents. A low moisture content of 10-15% enables storage without deterioration until use or sale. Beyond the care for initial drying, we also need to be aware of the purpose for which a plant is intended, so that the most suitable methods of processing are used.

In the nineteenth century, John Skelton gave some advice on the drying of herbs to herb-sellers, much of which is still applicable today (see panel, right), in his popular Family Medical Adviser, which was printed in at least 12 editions; Skelton was keen to ensure that herbs were properly dried and presented well. He advised on tidily bunching herbs for sale, tying with coarse grass and trimming the stems evenly, adding ‘I should also say be careful to put every herb you bunch, from the first to last, even[ly] at the top. Your bunches then look as if they had been gathered by a true botanist’, noting that he hated ‘your slovenly gatherers’.13

Harvesting stems for bark (from left to right): purging buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), bird cherry (Prunus padus) and ash (Fraxinus excelsior)

Advice on drying herbs

Directions for gathering and preserving

‘Roots. A very great number of our medicinal plants have their virtues in the roots, and unless they are gathered in proper season and carefully prepared, much, if not all that is truly valuable, may be entirely lost. The best time for gathering roots is in the spring, just before the leaves begin to shoot, for then they have their juices rich and full, and consequently their strength is the greatest. About the latter end of December, January, throughout February, and even at the beginning of March, are the best times when they should be sought for.’

‘Barks. Should be gathered in the spring, before the leaves begin to bud; they may then be peeled from the trees easily. The outside part or thin skin should be taken off. The bark should be broken into proper sizes, and hung to dry, in the same manner as roots.’

‘Herbs. Should be gathered when ripe, as soon as the leaves are in perfection, and when the sun is up, just as the flowers are ready to put forth their bloom. They should not be gathered when wet, either with the dew or by the rain. They should be tied loosely in small bunches, and hung up exposed to a free current of air. Press bunches into a strong box for several days, ensure the lid and side are removable so herbs can be taken out without breaking, pack in brown paper.’

‘Seeds. Require to be carefully gathered when perfectly ripe, to be carefully separated from the husks, spread upon a clean cloth on the floor, and exposed to a full current of air, until they are perfectly dry, after which they should be put into bags … inspect them occasionally to see that they are not getting mouldy … the least damp will destroy their virtues.’

Text extracted from Skelton J. (1878) Family Medical Adviser: A Treatise on Scientific or Botanic Medicine, 11th edition. Plymouth: Published by the author, pp.237-9.

* * *

Processing before drying

All plant material should be checked over for insects (leave outdoors for a few hours to allow these creatures to escape) and shaken to remove any loose matter. Washing is not usually necessary unless essential to remove dirt. Smaller quantities of herbs, twigs and stalks with flowers and leaves can be bundled up, tied with a rubber band and hung from rafters in an airy space indoors. Hanging the bundle inside a large paper bag is a way to protect the material from dust and insects. Once dry, flowers or leaves can then be readily rubbed off stalks, bagged and labelled. Plant parts that are more dense or substantial need to be chopped before drying in order to ensure a more even process of water loss. Fruits, such as berries, may need substantially longer to become thoroughly dried, and other processes than drying such as making syrups and fruit leathers may be worth considering (see Chapter 6 for sample recipes). Mushrooms can be dried whole unless large in which case they should be chopped into smaller similar-sized pieces of 1-2cm across. Roots should be trimmed to remove any damaged sections, then chopped into pieces of 1cm or less using a sharp knife, and the pieces placed in a single layer. It is also helpful to chop up bark into sections of less than 1-2cm long as they will be easier to handle at a later stage.

Best drying arrangements

Shaded, dry warmth with good air circulation creates the most favourable conditions for dehydrating fresh herbs. Airflow is crucial to the effective removal of water from plant material, and it can be increased by spreading herbs in thin layers, or using fans to move the air. Drying herbs must be kept in the shade and out of direct contact with sunlight. Different drying regimes can have a significant effect on medicinal constituents, particularly with regard to the temperatures used in drying.14 The optimal temperature for faster drying is generally thought to be between 30-40oC (86-104oF), requiring some additional heat beyond room temperature of around 20oC (68oF). In some cases a higher temperature may be justified. For example, fresh willow bark can be dried at 48oC (118oF) for 8-16 hours to reduce losses of phenolic content.15 Drying herbs should be protected at night from moist air which can rehydrate the herb and affect quality.16 Once dry, leaves should break up easily when rubbed in the hands or through a screen – stems and roots should be brittle enough to snap with a ‘crack’.17 When fully dried, the plant material can be bagged and labelled.

Drying equipment

For home production, with harvests of less than a kilogram, little is needed beyond general kitchen equipment including a sharp knife for chopping up bulkier items and a rack or screen for allowing herbs to dry. Homemade screens are ideal for spreading out herb material in thin layers, and can be constructed so that they stack easily. Larger quantities of herbs, such as 1-2kg or more in fresh weight, can be dried by spreading out on trays and placed in a shaded and well-ventilated area for 1-2 weeks. Overall the number of racks needed depends on weather, yields, speed of drying and number of crops being harvested. For more controlled drying, a dehydrator can be used which offers both a temperature setting and a timer. For commercial production there is a need to consider practical and economic aspects of providing a dryer system able to cope with larger quantities in adverse weather.18

At Holt Wood Herbs we have experimented with a number of arrangements for drying. A starting point was adapting a portable greenhouse with wire mesh shelves using a plastic cover painted black to attract heat and mesh-covered holes to encourage airflow. The design of our most effective dryer to date involves stacked catering trays on a moveable trolley with a fan and heating pad below, all surrounded by a plastic cover held in place with velcro. The drying effect appears to be improved with the plastic cover, which helps to funnel air up through and around the trays, and also serves to protect the crop in the trays. Development of further designs which make use of solar energy and wind power is desirable for drying plants.19

A drying rack with a layer of elder (Sambucus nigra) flowers

Further processing of herbs

Once a medicinal plant is dried, it can be stored whole, or processed into smaller pieces known as ‘cut herb’ in the trade, or powdered. This additional processing largely depends on whether the herb is to be used for alcohol or water extracts, or for other purposes such as filling capsules. The reduced size of plant particles can have a significant influence on the amounts of active constituents that are available in extracts. For example, a study of powdered particles of ginger ranging from 0.425-1.180mm in size found that the finer particles released the most anti-oxidants in an infusion.20 If herbs are grown for a manufacturer making medicinal products, then these supplies are usually provided in whole or coarser cut form (such as pieces 25-50mm), enabling the manufacturer to check identification and quality and then apply their own processing methods. For domestic culinary or herb tea uses the herb particles may need to be smaller, such as in a fine cut form up to 3mm in size.21

Crumbling and shredding

Small quantities of dried plants may be roughly crumbled by hand or broken up with a pestle and mortar. Screening is a method of separating a mixture of pieces into two or more size fractions, the over-sized materials are trapped above the screen, while undersized materials can pass through the screen. A simple but effective form of processing is to rub dried plant material through screens of wire mesh of different sizes. A number of scales are used to classify screens or sieves and particle sizes including the US sieve series and Tyler mesh size (based on number of openings in the width of one inch). Larger mesh sizes may be given as the size of opening in millimetres or inches. Some sizes of mesh opening are given on the right and screens at some of these sizes may be available at beekeeper suppliers. If using a rubbing screen it is helpful to set up a frame with a tray or sheet below to catch the material. A chaffcutter may be considered for larger quantities of plant material, and can be hand-operated or sometimes can be mechanised with the addition of an electric motor. An alternative to the chaffcutter is an electric shredder dedicated for use with dried herbs. This is what we use at Holt Wood, and we deliberately selected a model which can be readily taken apart for cleaning between batches of herb.22

Comparative sieve sizes for screening herbs

US sieve size |

Tyler equivalent |

Opening sizemm inches |

Ideal for |

|

|

5/8 inch |

– |

16.00 |

0.625 |

Coarse cut |

|

5/16 inch |

2.5 Mesh |

8.00 |

0.312 |

|

|

No.5 |

5 Mesh |

4.00 |

0.157 |

|

|

No.10 |

9 Mesh |

2.00 |

0.787 |

|

|

No.20 |

20 Mesh |

0.841 |

0.0331 |

Coarse powder |

|

No.40 |

35 Mesh |

0.42 |

0.0165 |

Coarse powder |

|

No.60 |

60 Mesh |

0.25 |

0.0098 |

Fine powder |

|

No.120 |

115 Mesh |

0.125 |

0.0049 |

Fine powder |

Adapted from Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mesh_%28scale%29#Sieve_sizing_and_conversion_charts and US Pharmacopoeia, www.pharmacopeia.cn/usp.asp (accessed 25 March 2019).

Powdering

Once the pieces of a dried medicinal plant are reduced in size, then they can be further processed by powdering. Processing to particle size suitable for use as a coarse or fine powder can add considerable value to herbs, as they then have a range of uses including percolation as a fluid extract or filling capsules. At Holt Wood we harvest cramp bark and after drying it is powdered for making capsules or tincture (see Harvesting Cramp Bark, below). However, it should be noted that powdering does reduce the length of storage time possible for the herb material. For small quantities, hand powdering of dried herb can be done using a pestle and mortar or a coffee bean grinder, with repeated sieving to remove fibrous material. A hand-operated grain grinder also provides an effective way of grinding dried plant material, and can be adjusted to provide coarse or fine particles.

Dried bark is fed into a hammermill grinder (left to right from top): feed tray with dried ash (Fraxinus excelsior) bark; controls; chamber where bark is ground; screens used to reduce particle size

For larger quantities of herbs, a hammermill grinder can process cut herbs into pharmacy grade powder by using metal screens, and is suitable for long runs with a continuous feed for powdering dried bark, leaves, roots and twigs.23 The hammermill screens come with a range of different aperture sizes, so that particle size can be reduced in stages without overheating the plant material.

Powdering of dried herbs can produce a lot of dust! Protective equipment may be necessary for processing of drying herbs, to avoid dust inhalation and irritants to the skin and eyes. Flexible leather gloves with long cuffs are suitable for handling and for rubbing herbs. A dust mask, such as a disposable paper mask used in building and decorating, is probably suitable for working with most dried herbs. Ear protection may be needed if machinery is used.24 Take particular care with machine use and select a wooden tool rather than fingers to push herbal material through the machine. Powdering of herbs should always be done in a well-ventilated area.

Harvesting cramp bark

The author harvesting cramp bark

Name: Holt Wood Herbs

Location: Devon

Activity: Cramp bark (Viburnum opulus) is an antispasmodic remedy, also known as guelder rose or snowball tree. It is ideal for use in reducing menstrual cramps and other colicky complaints. In Holt Wood we planted cramp bark whips, 40-60cm, at the edge of newly planted woodland areas prone to flooding. Apart from fencing for deer protection, and bi-annual strimming around the shrubs, no other special measures were taken. Spacing of the plants varied but averaged approximately 1.5-2m apart. After several years, each shrub, having reached a height of approximately 2m, provided five to six stems. In early spring the stems were cut off at a height of 10-20cm from the ground. Leaves and twigs less than a pencil in thickness were removed, and this material was used for compost or mulching elsewhere on the site. The cleaned branches were then stripped of bark using a curved blade (a boning knife was found to be ideal). These bark pieces were dried at 20oC (68oF) for three weeks and then cut and ground to powder. Quantity of fresh stem bark per plant averaged 350g which meant that, after drying, 1kg of dried powdered bark could be gained from six shrubs (this would be the equivalent of 2500 capsules containing 400mg powder per capsule). The remaining branches, having been stripped of bark, were chipped for mulching paths. The coppiced stumps can be left to regenerate over subsequent years.

Key point: A sustainable harvest of cramp bark can be readily produced using coppicing techniques.

Info: https://www.holtwoodherbs.com

Cramp bark stems ready to peel for bark

* * *

Storage of dried herbs

Dried herbs ideally need to be stored in cool, dark and dry conditions to limit further degradation. They need to be checked regularly in case of mould due to inadequate drying or infestation by insects. Plant material that is beyond its use by date can be recycled in compost or as a mulch on soil. The length of time during which plant materials can be reasonably expected to last without deterioration varies according to the part of plant and the amount of cutting and powdering done (see table below).

Sample label format for harvested plants. Adapted from Whitten G. (1997) Herbal Harvest: Commercial Organic Production of Quality Dried Herbs, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia: Bloomings Books, p.221.

Generally, the greater the level of processing, the greater surface area in the herb material for further oxidation and degradation, so powder is most vulnerable. For short-term storage of dried herb material, paper or cotton bags can be used, closed with string or elastic bands, but these will allow in moisture unless they are further packed within moisture-proof bags or containers. For longer-term storage a variety of suitable containers can be used to prevent moisture and insects from getting in, such as large glass jars or plastic bins. Recycled food grade plastic tubs with sealable lids are ideal as containers to prevent dust, insects or vermin. An advantage of glass or clear plastic is that it allows inspection of the material inside. More substantial protection may be needed if the herbs are to be transported and large woven polypropylene sacks with inner liners can be obtained for this purpose.

Storage times for dried plants

Material |

Length of storage |

|

Roots, whole |

2-5 years |

|

Roots, cut |

2 years |

|

Roots, powdered |

1 year |

|

Leaves, stems or flowers, whole |

2 years |

|

Leaves, stems or flowers, powdered or cut |

1 year |

|

Bark, cut |

2 years |

|

Bark, powdered |

1 year |

|

Seeds, whole |

up to 10 years in cold conditions < 10oC |

|

Seeds, powdered |

1 year |

|

Fruits, whole |

2 years |

Pillowcases can be used for carrying the harvest

Insect contamination

Freezing can be used to doublecheck that plant material is not contaminated by insects. Herb material can be frozen in a domestic freezer at between -18 and -20oC (0 to -4oF) to ensure that no viable insects or their eggs are present. To do this, place the dried herb material in a plastic bag and seal at room temperature. Then put the bag in a freezer and enable the fast freeze option if available. The purpose of freezing rapidly is to ensure that insects cannot protect themselves against the cold (some insects can produce a natural antifreeze). If a large quantity of material needs to be frozen then it would be best to decant into smaller bags to ensure fast freezing. Keep the plant material in the freezer for 3-7 days. Then remove the bags of material and allow to return to room temperature for 24 hours without opening in order to avoid condensation dampening the herbs. Record the dates that the bags were inserted and removed from the freezer.

Keeping records of the harvest

Our experience at Holt Wood has been that there is an abundance of healing plants growing. We have needed to find efficient ways of processing the harvest to maximise quality and keep it well. We have found that it is vital to label (see the label format in the example above) and keep records of harvests as a good practice measure. Our harvest record book provides batch numbers which can be used to trace particular plants from harvest to use in preparations. The date of harvest is noted alongside the plant name and part, as well as the person who confirmed the plant’s identity. Further useful information recorded is the fresh weight of the plant harvested and any particular key details about the source – for example, for trees this could be the location and/or the size measured as diameter at breast height. Additional details are added at a later stage of how the batch is processed, for example giving dried weight and quality. Measurements like this for agriculture and timber production are well established, but much less so for herbal plant cultivation or non-timber forest products.25 Keeping such records of harvests will go a long way towards providing a set of data which builds up year by year. In the future we hope to compare yields between sites, and to relate them to environmental and other changes.

1 Hart (1991) p111.

2 For more on harvesting or foraging from wilder places, see Bruton-Seal J and Seal M. (2008) Hedgerow Medicine: Harvest and Make Your Own Herbal Remedies, Ludlow: Merlin Unwin Books; Hawes Z. (2010) Wild Drugs: A Forager’s Guide to Healing Plants, London: Gaia.

3 Henkel A. (1909) American Medicinal Barks, Washington: US Department of Agriculture, p8.

4 Rohloff J, Dragland S, Mordal R, et al. (2005) Effect of harvest time and drying method on biomass production, essential oil yield, and quality of peppermint (Mentha × piperita L.). J Agric Food Chem 53: 4143-4148.

5 Sibao C, Dajian Y, Shilin C, et al. (2007) Seasonal variations in the isoflavonoids of radix Puerarae. Phytochem Anal 18: 245-250.

6 Li SL, Yan R, Tam YK, et al. (2007) Post-harvest alteration of the main chemical ingredients in Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. (Rhizoma Chuanxiong). Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 55: 140-144.

7 Higman et al. (2005) p167-169.

8 Such as Stace C. (2019) New flora of the British Isles, 4th edition, Middlewood Green, Suffolk: C&M Floristics; Rose F. (2006) The Wild Flower Key: How to Identify Wild Plants, Trees and Shrubs in Britain and Ireland, London: Frederick Warne; Mitchell A. (1974) A Field Guide to the Trees of Britain and Northern Europe, London: Collins.

9 There have been reports of contamination of some Western herbs with leaves of potentially toxic plants such as deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna), foxglove (Digitalis species) and ragworts (Senecio species); Mills SY and Bone K. (2005) The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety, St Louis: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, pp108-109.

10 Whitten G. (1997) Herbal Harvest: Commercial Organic Production of Quality Dried Herbs, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia: Bloomings Books, pp139-140.

11 Whitten (1997) pp147-148.

12 A more detailed explanation of voucher specimen standards is available in Hildreth J, Hrabeta-Robinson E, Applequist W, et al. (2007) Standard operating procedure for the collection and preparation of voucher plant specimens for use in the nutraceutical industry. Anal Bioanal Chem 389: 13-17.

13 Skelton, J. (1878) Family Medical Adviser: A Treatise on Scientific or Botanic Medicine, 11th edn, Plymouth: Published by the author.

14 Li et al. (2007), in their study of processing of a Chinese root, found that drying at 60oC meant that some compounds were decreased, some increased and some new compounds appeared.

15 Upton R. (ed.) (1999) Willow Bark, Salix spp. Analytical, Quality Control and Therapeutic Monograph, Santa Cruz: America Herbal Pharmacopoeia.

16 Lonner J and Thomas M. (2003) A Harvester’s Handbook to Wild Medicinal Plant Collection in Kosovo, Kosovo Business Support, p5.

17 Whitten (1997) pp151-153.

18 Ibid. pp155-156. Whitten also provides instructions for building a small cabinet dryer – 950 × 1500 × 2400mm to take 13 screens with a 1000W heat source, pp173-176.

19 Scanlin D. (2014) ‘Best-ever solar food dehydrator plans’, Mother Earth News. Available at: www.motherearthnews.com/diy/tools/solar-food-dehydrator-plans-zm0z14jjzmar (accessed 6 May 2018).

20 Makanjuola SA. (2017) Influence of particle size and extraction solvent on anti-oxidant properties of extracts of tea, ginger, and tea-ginger blend. Food Sci Nutr 5: 1179-1185.

21 Whitten (1997) pp197-198.

22 Our model at Holt Wood is a Titan 2500W Rapid Garden Shredder, and the front panel can be removed in order to clean the cutting blade within.

23 At Holt Wood we use a FDS Continuous Feed Powdering Machine, an accessory supplied by Mayway Herbs, Oakland, California, USA, www.mayway.com/supplies/accessories (accessed 30 July 2019).

24 Whitten (1997) p204.

25 Cunningham AB. (2001) Applied Ethnobotany: People, Wild Plant Use and Conservation, London: Earthscan.