Chapter 9

On Empathy and Emotion

Why We Respond to One Person Who Needs Help but Not to Many

Few Americans who were alive and cognizant in 1987 could forget the “Baby Jessica” saga. Jessica McClure was an eighteen-month-old girl in Midland, Texas, who was playing in the backyard at her aunt’s house when she fell twenty-two feet down an abandoned water well. She was wedged in the dark, subterranean crevice for 58½ hours, but the infinitesimally drawn-out media coverage made it seem as if the ordeal dragged on for weeks. The drama brought people together. Oil drillers–cum–rescue workers, neighbors, and reporters in Midland stood daily vigil, as did television viewers around the globe. The whole world followed every inch of progress in the rescue effort. There was deep consternation when rescuers discovered that Jessica’s right foot was wedged between rocks. There was universal delight when workers reported that she’d sung along to the Humpty-Dumpty nursery rhyme that was piped down to her by a speaker lowered into the shaft (an interesting choice, considering the circumstances). Finally, there was the tearful relief when the little girl was finally pulled out of the laboriously drilled parallel shaft.

In the aftermath of the rescue, the McClure family received more than $700,000 in donations for Jessica. Variety and People magazine ran gripping stories on her. Scott Shaw of the Odessa American newspaper won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for his photograph of the swaddled toddler in the arms of one of her rescuers. There was a TV movie called Everybody’s Baby: The Rescue of Jessica McClure, starring Beau Bridges and Patty Duke, and the songwriters Bobby George Dynes and Jeff Roach immortalized her in ballads.

Of course, Jessica and her parents suffered a great deal. But why, at the end of the day, did Baby Jessica garner more CNN coverage than the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, during which 800,000 people—including many babies—were brutally murdered in a hundred days? And why did our hearts go out to the little girl in Texas so much more readily than to the victims of mass killings and starvation in Darfur, Zimbabwe, and Congo? To broaden the question a bit, why do we jump out of our chairs and write checks to help one person, while we often feel no great compulsion to act in the face of other tragedies that are in fact more atrocious and involve many more people?

It’s a complex topic and one that has daunted philosophers, religious thinkers, writers, and social scientists since time immemorial. Many forces contribute to a general apathy toward large tragedies. They include a lack of information as the event is unfolding, racism, and the fact that pain on the other side of the world doesn’t register as readily as, say, our neighbors’. Another big factor, it seems, has to do with the sheer size of the tragedy—a concept expressed by none other than Joseph Stalin when he said, “One man’s death is a tragedy, but a million deaths is a statistic.” Stalin’s polar opposite, Mother Teresa, expressed the same sentiment when she said, “If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at one, I will.” If Stalin and Mother Teresa not only agreed (albeit for vastly different reasons) but were also correct on this score, it means that though we may possess incredible sensitivity to the suffering of one individual, we are generally (and disturbingly) apathetic to the suffering of many.

Can it really be that we care less about a tragedy as the number of sufferers increases? This is a depressing thought, and I will forewarn you that what follows will not make for cheerful reading—but, as is the case with many other human problems, it is important to understand what really drives our behavior.

The Identifiable Victim Effect

To better understand why we respond more to individual suffering than to that of the masses, allow me to walk you through an experiment carried out by Deborah Small (a professor at the University of Pennsylvania), George Loewenstein, and Paul Slovic (founder and president of Decision Research). Deb, George, and Paul gave participants $5 for completing some questionnaires. Once the participants had the money in hand, they were given information about a problem related to food shortage and asked how much of their $5 they wanted to donate to fight this crisis.

As you must have guessed, the information about the food shortage was presented to different people in different ways. One group, which was called the statistical condition, read the following:

Food shortages in Malawi are affecting more than 3 million children. In Zambia, severe rainfall deficits have resulted in a 42% drop in the maize production from 2000. As a result, an estimated 3 million Zambians face hunger. 4 million Angolans—one third of the population—have been forced to flee their homes. More than 11 million people in Ethiopia need immediate food assistance.

Participants were then given the opportunity to donate a portion of the $5 they just earned to a charity that provided food assistance. Before reading on, ask yourself, “If I were in a participant’s shoes, how much would I give, if anything?”

The second group of participants, in what was called the identifiable condition, was presented with information about Rokia, a desperately poor seven-year-old girl from Mali who faced starvation. These participants looked at her picture and read the following statement (which sounds as if it came straight from a direct-mail appeal):

Her life would be changed for the better as a result of your financial gift. With your support, and the support of other caring sponsors, Save the Children will work with Rokia’s family and other members of the community to help feed her, provide her with an education, as well as basic medical care and hygiene education.

As was the case in the statistical condition, participants in the identifiable condition were given the opportunity to donate some or all of the $5 they had just earned. Again, ask yourself how much you might donate in response to the story of Rokia. Would you give more of your money to help Rokia or to the more general fight against hunger in Africa?

If you were anything like the participants in the experiment, you would have given twice as much to Rokia as you would to fight hunger in general (in the statistical condition, the average donation was 23 percent of participants’ earnings; in the identifiable condition, the average was more than double that amount, 48 percent). This is the essence of what social scientists call “the identifiable victim effect”: once we have a face, a picture, and details about a person, we feel for them, and our actions—and money—follow. However, when the information is not individualized, we simply don’t feel as much empathy and, as a consequence, fail to act.

The identifiable victim effect has not escaped the notice of many charities, including Save the Children, March of Dimes, Children International, the Humane Society, and hundreds of others. They know that the key to our wallets is to arouse our empathy and that examples of individual suffering are one of the best ways to ignite our emotions (individual examples  emotions

emotions  wallets).

wallets).

IN MY OPINION, the American Cancer Society (ACS) does a tremendous job of implementing the underlying psychology of the identifiable victim effect. The ACS understands not only the importance of emotions but also how to mobilize them. How does the ACS do it? For one thing, the word “cancer” itself creates a more powerful emotional imagery than a more scientifically informative name such as “transformed cell abnormality.” The ACS also makes powerful use of another rhetorical tool by dubbing everyone who has ever had cancer a “survivor” regardless of the severity of the case (and even if it’s more likely that a person would die of old age long before his or her cancer could take its toll). An emotionally loaded word such as “survivor” lends an additional charge to the cause. We don’t use that word in connection with, say, asthma or osteoporosis. If the National Kidney Foundation, for example, started calling anyone who had suffered from kidney failure a “renal failure survivor,” wouldn’t we give more money to fight this very dangerous condition?

On top of that, conferring the title “survivor” on anyone who has had cancer makes it possible for the ACS to create a broad and highly sympathetic network of people who have a deep personal interest in the cause and can create more personal connections to others who don’t have the disease. Through the ACS’s many sponsorship-based marathons and charity events, people who would otherwise not be directly connected to the cause end up donating money—not necessarily because they are interested in cancer research and prevention but because they know a cancer survivor. Their concern for that one person motivates them to give their time and money to the ACS.

Closeness, Vividness, and the “Drop-in-the-Bucket” Effect

The experiment and anecdotes I just described demonstrate that we are willing to spend money, time, and effort to help identifiable victims yet fail to act when confronted with statistical victims (say, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans). But what are the reasons for this pattern of behavior? As is the case for many complex social problems, here too there are multiple psychological forces in play. But before we discuss these in more detail, try the following thought experiment:*

Imagine that you are in Cambridge, Massachusetts, interviewing for your dream job. You have an hour before your interview, so you decide to walk to your appointment from your hotel in order to see some of the city and clear your head. As you walk across a bridge over the Charles River, you hear a cry below you. A few feet up the river, you see a little girl who seems to be drowning—she’s calling for help and gasping for air. You are wearing a brand-new suit and snappy accoutrements, all of which has cost you quite a bit of money—say, $1,000. You’re a good swimmer, but you have no time to remove anything if you want to save her. What do you do? Chances are you wouldn’t think much; you’d simply jump in to save her, destroying your new suit and missing your job interview. Your decision to jump in is certainly a reflection of the fact that you are a kind and wonderful human being, but it might also be due partially to three psychological factors.*

First, there’s your proximity to the victim—a factor psychologists refer to as closeness. Closeness doesn’t just refer to physical nearness, however; it also refers to a feeling of kinship—you are close to your relatives, your social group, and to people with whom you share similarities. Naturally (and thankfully), most of the tragedies in the world are not close to us in terms of physical or psychological proximity. We don’t personally know the vast majority of the people who are suffering, and therefore it is hard for us to feel as much empathy for their pain as we might for a relative, friend, or neighbor in trouble. The effect of closeness is so powerful that we are much more likely to give money to help a neighbor who has lost his high-paying job than to a much needier homeless person who lives one town over. And we will be even less likely to give money to help someone whose home has been lost to an earthquake three thousand miles away.

The second factor is what we call vividness. If I tell you that I’ve cut myself, you don’t get the full picture and you don’t feel much of my pain. But if I describe the cut in detail with tears in my voice and tell you how deep the wound is, how much the torn skin hurts me, and how much blood I’m losing, you get a more vivid picture and will empathize with me much more. Likewise, when you can see a drowning victim and hear her cries as she struggles in the cold water, you feel an immediate need to act.

The opposite of vividness is vagueness. If you are told that someone is drowning but you don’t see that person or hear their cry, your emotional machinery is not engaged. Vagueness is a bit like looking at a picture of Earth taken from space; you can see the shape of the continents, the blue of the oceans, and the large mountain ridges, but you don’t see the details of traffic jams, pollution, crime, and wars. From far away, everything looks peaceful and lovely; we don’t feel the need to change anything.

The third factor is what psychologists call the drop-in-the-bucket effect, and it has to do with your faith in your ability to single-handedly and completely help the victims of a tragedy. Think about a developing country where many people die from contaminated water. The most each of us can do is go there ourselves and help build a clean well or sewage system. But even that intense level of personal involvement will save only a few people, leaving millions of others still in desperate need. In the face of such large needs, and given the small part of it that we can personally solve, one may be tempted to shut down emotionally and say, “What’s the point?”*

TO THINK ABOUT how these factors might influence your own behavior, ask yourself the following questions: What if the drowning girl lived in a faraway land hit by a tsunami and you could, at a very moderate expense (much less than the $1,000 that your suit cost you), help save her from her fate? Would you be just as likely to “jump in” with your dollars? Or what if the situation involved a less vivid and immediate danger to her life? For example, let’s say she was in danger of contracting malaria. Would your impulse to help her be just as strong? Or what if there were many, many children like her in danger of developing diarrhea or HIV/AIDS (and there are)? Would you feel discouraged by your inability to completely solve the problem? What would happen to your motivation to help?

If I were a betting man, I would wager that your desire to act to save many kids who are slowly contracting a disease in a faraway land is not that high compared with the urge to help a relative, friend, or neighbor who is dying of cancer. (Lest you feel that I’m picking on you, you should know that I behave exactly the same way.) It is not that you are hard-hearted, it is just that you are human—and when a tragedy is faraway, large, and involves many people, we take it in from a more distant, less emotional, perspective. When we can’t see the small details, suffering is less vivid, less emotional, and we feel less compelled to act.

IF YOU STOP to think about it, millions of people around the world are essentially drowning every day from starvation, war, and disease. And despite the fact that we could achieve a lot at a relatively small cost, thanks to a combination of closeness, vividness, and the drop-in-the-bucket effect, most of us don’t do much to help.

Thomas Schelling, the Nobel laureate in economics, did a good job describing the distinction between an individual life and a statistical life when he wrote:

Let a 6-year-old girl with brown hair need thousands of dollars for an operation that will prolong her life until Christmas, and the post office will be swamped with nickels and dimes to save her. But let it be reported that without a sales tax the hospital facilities of Massachusetts will deteriorate and cause a barely perceptible increase in preventable deaths—not many will drop a tear or reach for their checkbooks.17

How Rational Thought Blocks Empathy

All this appeal to emotion raises the question: what if we could make people more rational, like Star Trek’s Mr. Spock? Spock, after all, was the ultimate realist: being both rational and wise, he would realize that it’s most sensible to help the greatest number of people and take actions that are proportional to the real magnitude of the problem. Would a colder view of problems prompt us to give more money to fight hunger on a larger scale than helping little Rokia?

To test what would happen if people thought in a more rational and calculated manner, Deb, George, and Paul designed another interesting experiment. At the start of this experiment, they asked some of the participants to answer the following question: “If a company bought 15 computers at $1,200 each, then, by your calculation, how much did the company pay in total?” This was not a complex mathematical question; its goal was to prime (the general term psychologists use for putting people in a particular, temporary state of mind) the participants so that they would think in a more calculating way. The other participants were asked a question that would prime their emotions: “When you hear the name George W. Bush, what do you feel? Please use one word to describe your predominant feeling.”

After answering these initial questions, the participants were given the information either about Rokia as an individual (the identifiable condition) or about the general problem of food shortage in Africa (the statistical condition). Then they were asked how much money they would donate to the given cause. The results showed that those who were primed to feel emotion gave much more money to Rokia as an individual than to help fight the more general food shortage problem (just as in the experiment without any priming). The similarity of the results when participants were primed with emotions and when they were not primed at all suggests that even without emotional priming, participants relied on their feelings of compassion when making their donation decisions (that is why adding an emotional prime did not change anything—it was already part of the decision process).

And what about the participants who were primed to be in a calculating, Spock-like state of mind? You might expect that more calculated thinking would cause them to “fix” the emotional bias toward Rokia and so to give more to help a larger number of people. Unfortunately, those who thought in a more calculated way became equal-opportunity misers by giving a similarly small amount to both causes. In other words, getting people to think more like Mr. Spock reduced all appeal to compassion and, as a consequence, made the participants less inclined to donate either to Rokia or to the food problem in general. (From a rational point of view, of course, this makes perfect sense. After all, a truly rational person would generally not spend any money on anything or anyone that would not produce a tangible return on investment.)

I FOUND THESE results very depressing, but there was more. The original experiment that Deb, George, and Paul carried out on the identifiable victim effect—the one in which participants gave twice as much money to help Rokia as to fight hunger in general—had a third condition. In this condition, participants received both the individual information about Rokia and the statistical information about the food problem simultaneously (without any priming).

Now try to guess the amount that participants donated. How much do you think they gave when they learned about both Rokia and the more general food shortage problem at the same time? Would they give the same high amount as when they learned only about Rokia? Or would they offer the same low amount as when the problem was presented in a statistical way? Somewhere in the middle? Given the depressing tone of this chapter, you can probably guess the pattern of results. In this mixed condition, the participants gave 29 percent of their earnings—slightly higher than the 23 percent that the participants in the statistical condition gave but much lower than the 48 percent donated in the individualized condition. Simply put, it turned out to be extremely difficult for participants to think about calculation, statistical information, and numbers and to feel emotion at the same time.

Taken together, these results tell a sad story. When we’re led to care about individuals, we take action, but when many people are involved, we don’t. A cold calculation does not increase our concern for large problems; instead, it suppresses our compassion. So, while more rational thinking sounds like good advice for improving our decisions, thinking more like Mr. Spock can make us less altruistic and caring. As Albert Szent-Györgi, the famous physician and researcher, put it, “I am deeply moved if I see one man suffering and would risk my life for him. Then I talk impersonally about the possible pulverization of our big cities, with a hundred million dead. I am unable to multiply one man’s suffering by a hundred million.”18

Where Should the Money Go?

These experiments might make it seem that the best course of action is to think less and use only our feelings as a guide when making decisions about helping others. Unfortunately, life is not that simple. Though we sometimes don’t step in to help when we should, at other times we act on behalf of the suffering when it’s irrational (or at least inappropriate) to do so.

For example, a few years ago a two-year-old white terrier named Forgea spent three weeks alone aboard a tanker drifting in the Pacific after its crew abandoned ship. I’m sure Forgea was adorable and didn’t deserve to die, but one can ask whether, in the grand scheme of things, saving her was worth a twenty-five-day rescue mission that cost $48,000 of taxpayers’ money—an amount that might have been better spent caring for desperately needy humans. In a similar vein, consider the disastrous oil spill from the wrecked Exxon Valdez. The estimates for cleaning and rehabilitating a single bird were about $32,000 and for each otter about $80,000.19 Of course, it’s very hard to see a suffering dog, bird, or otter. But does it really make sense to spend so much money on an animal when doing so takes away resources from other things such as immunization, education, and health care? Just because we care more about vivid examples of misery doesn’t mean that this tendency always helps us to make better decisions—even when we want to help.

Think again about the American Cancer Society. I have nothing against the good work of the ACS, and if it were a business, I would congratulate it on its resourcefulness, its understanding of human nature, and its success. But in the nonprofit world, there is some bitterness against the ACS for having been “overly successful” in capturing the enthusiastic support of the public and leaving other equally important causes wanting. (The ACS is so successful that there are several organized efforts to ban donations to what is called “the world’s wealthiest nonprofit.”20) In a way, if people who give to the ACS don’t give as much to other non-cancer charities, the other causes become victims of the ACS’s success.

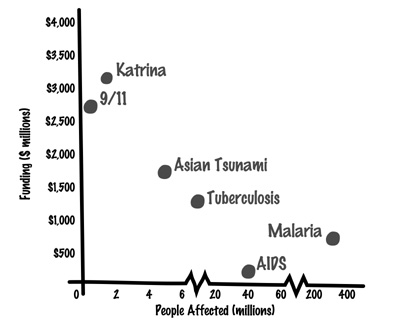

Mismatching money and need: The number of people (in millions) affected by different tragedies and the amount of money (in millions of dollars) directed toward these tragedies

TO THINK ABOUT the problem of misallocation of resources in more general terms, consider the graph on the previous page.21 It depicts the amount of money donated to help victims across a variety of catastrophes (Hurricane Katrina, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the tsunami in Asia, tuberculosis, AIDS, and malaria) and the number of people these tragedies affected directly.

The graph clearly shows that in these cases, as the number of sufferers increased, the amount of money donated decreased. We can also see that more money went to U.S.-based tragedies (Hurricane Katrina and the terrorist attacks of 9/11) than to non-U.S. ones, such as the tsunami. Perhaps more disturbingly, we also see that prevention of diseases such as tuberculosis, AIDS, and malaria received very little funding relative to the magnitude of those problems. That is probably because prevention is directed at saving people who are not yet sick. Saving hypothetical people from potential future disease is too abstract and distant a goal for our emotions to take hold and motivate us to open our wallets.

Consider another large problem: CO2 emissions and global warming. Regardless of your personal beliefs on this matter, this type of problem is the toughest kind to get people to care about. In fact, if we tried to manufacture an exemplary problem that would inspire general indifference, it would probably be this. First of all, the effects of climate change are not yet close to those living in the Western world: rising sea levels and pollution may affect people in Bangladesh, but not yet those living in the heartland of America or Europe. Second, the problem is not vivid or even observable—we generally cannot see the CO2 emissions around us or feel that the temperature is changing (except, perhaps, for those coughing in L.A. smog). Third, the relatively slow, undramatic changes wrought by global warming make it hard for us to see or feel the problem. Fourth, any negative outcome from climate change is not going to be immediate; it will arrive at most people’s doorsteps in the very distant future (or, as climate-change skeptics think, never). All of these reasons are why Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth relied so heavily on images of drowning polar bears and other vivid imagery; they were his way of tapping into our emotions.

Of course, global warming is the poster child for the drop-in-the-bucket effect. We can cut back on driving and change all our lightbulbs to highly efficient ones, but any action taken by any one of us is far too small to have a meaningful influence on the problem—even if we realize that a great number of people making small changes can have a substantial effect. With all these psychological forces working against our tendency to act, is it any surprise that there are so many huge and growing problems around us—problems that, by their very nature, do not evoke our emotion or motivation?

How Can We Solve the Statistical Victim Problem?

When I ask my students what they think will inspire people to get out of their chairs, take some action, donate, and protest, they tend to answer that “lots of information” about the magnitude and severity of the situation is most likely the best way to inspire action. But the experiments described above show that this isn’t the case. Sadly, our intuitions about the forces that motivate human behavior seem to be flawed. If we were to follow my students’ advice and describe tragedies as large problems affecting many people, action would most likely not happen. In fact, we might achieve the opposite and suppress a compassionate response.

This raises an important question: if we are called to action only by individual, personalized suffering and are numbed when a crisis outgrows our ability to imagine it, what hope do we have of getting ourselves (or our politicians) to solve large-scale humanitarian problems? Clearly, we cannot simply trust that we will all do the right thing when the next disaster inevitably takes place.

It would be nice (and I realize that that the word “nice” here isn’t really appropriate) if the next catastrophe were immediately accompanied by graphic photos of individuals suffering—maybe a dying kid that can be saved or a drowning polar bear. If such images were available, they would incite our emotions and propel us into action. But all too often, images of disaster are too slow to appear (as was the case in Rwanda) or they depict a large statistical rather than identifiable suffering (think, for example, about Darfur). And when these emotion-evoking images finally appear on the public stage, action may be too late in coming. Given all our human barriers to solving the significant problems we face, how can we shake off our feelings of despair, helplessness, and apathy in the face of great misery?

ONE APPROACH IS to follow the advice given to addicts: that the first step in overcoming any addiction is recognizing the problem. If we realize that the sheer size of a crisis causes us to care less rather than more, we can try to change the way we think and approach human problems. For example, the next time a huge earthquake flattens a city and you hear about thousands of people killed, try to think specifically about helping one suffering person—a little girl who dreams of becoming a doctor, a graceful teenage boy with a big smile and a talent for soccer, or a hardworking grandmother struggling to raise her deceased daughter’s child. Once we imagine the problem this way, our emotions are activated, and then we can decide what steps to take. (This is one reason why Anne Frank’s diary is so moving—it’s a portrayal of a single life lost among millions.) Similarly, you can also try to counteract the drop-in-the-bucket effect by reframing the magnitude of the crisis in your mind. Instead of thinking about the problem of massive poverty, for example, think about feeding five people.

We can also try to change our ways of thinking, taking the approach that has made the American Cancer Society so successful in fund-raising. Our emotional biases that favor nearby, singular, vivid events can stir us to action in a broader sense. Take the psychological feeling of closeness, for example. If someone in our family develops cancer or multiple sclerosis, we may be inspired to raise money for research on that particular disease. Even an admired person who is personally unknown to us can inspire a feeling of closeness. For example, since being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1991, Michael J. Fox has lobbied for research funding and worked to educate the public about the disease. People who loved Family Ties and Back to the Future associate his face with his cause, and they come to care about it. When Michael J. Fox asks donors to support his foundation, it can sound a little self-serving—but actually it’s quite effective in raising money to help Parkinson’s sufferers.

ANOTHER APPROACH IS to come up with rules to guide our behavior. If we can’t trust our hearts to always drive us to do the right thing, we might benefit from creating rules that will direct us to take the right course of action, even when our emotions are not aroused. For example, in the Jewish tradition there is a “rule” that is designed to fight the drop-in-the-bucket effect. According to the Talmud, “whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.”22 With such a guideline at hand, religious Jews might be able to overcome the natural tendency not to act when all we can do is solve a small part of the problem. On top of that, the way the rule is defined (“as if he saved an entire world”) makes it easier to imagine that, by saving even just one person, we can actually do something complete and enormous.

The same approach of creating clear moral principles can work in cases where clear humanitarian principles apply. Consider again what happened in the Rwanda massacre. The United Nations was too slow to react and stop it, even when doing so might not have required a large intervention. (The UN general in the region, Roméo Dallaire, did in fact, ask for 5,000 troops in order to stop the impending slaughter, but his request was denied.) Year after year, we hear about massacres and genocides around the globe, and often help comes too late. But imagine that the United Nations were to enact a law stating that every time the lives of a certain number of people were in danger (in the judgment of a leader close to the situation, such as General Dallaire), it would immediately send an observing force to the area and call a meeting of the Security Council with a requirement that a decision about next steps be taken within forty-eight hours.* Through such a commitment to rapid action, many lives could be saved.

This is also how governments and not-for-profit organizations should look at their mission. It is politically easier for such organizations to help causes that the general population is interested in, but those causes often already receive some funding. It is causes that are not personally, socially, or politically appealing that usually don’t receive the investments they deserve. Preventative health care is perhaps the best example of this. Saving people who are not yet sick, or who aren’t even born, isn’t as inspiring as saving a single polar bear or orphaned child, because future suffering is intangible. By stepping in where our emotions don’t compel us to act, governments and NGOs can make a real difference in fixing the helping imbalance and hopefully reduce or eliminate some of our problems.

IN MANY WAYS, it is very sad that the only effective way to get people to respond to suffering is through an emotional appeal, rather than through an objective reading of massive need. The upside is that when our emotions are awakened, we can be tremendously caring. Once we attach an individual face to suffering, we’re much more willing to help, and we go far beyond what economists would expect from rational, selfish, maximizing agents. Given this mixed blessing, we should realize that we are simply not designed to care about events that are large in magnitude, take place far away, or involve many people we don’t know. By understanding that our emotions are fickle and how our compassion biases work, perhaps we can start making more reasonable decisions and help not only those who are trapped in a well.