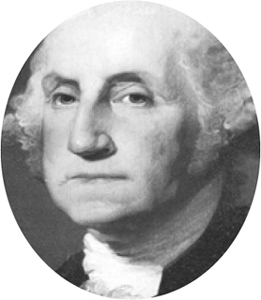

GENERAL, PRESIDENT, DISTILLER

1732–1799

![]()

Mount Vernon Estate, Mount Vernon, Virginia

The fact that George Washington distilled whiskey is not his most significant contribution to American history, though many have used it to bolster both sides of the temperance debate over the centuries. The story begins, perhaps, with young George prowling around Western Pennsylvania in 1754, ostensibly to provoke the French at the fort at Pittsburgh and assert a claim to the territory for the British. Washington crossed a small river at a site that would eventually become one of the largest distilleries in the country, at Broad Ford (see Henry Clay Frick, this page). After a little skirmish near Fort Duquesne, the French stronghold in Pittsburgh, Washington retreated to what was later called Fort Necessity, essentially a circle of wood pickets in a meadow situated in a mountain pass, and the most defensible position from which to await supplies. Those supplies never came, and Washington’s troops ran out of everything except whiskey. When the French arrived, they were eager for action, but Washington found himself outmatched (and his troops, having broken into the liquor stash, were not in the best condition to fight); he surrendered for the only time in his career. One would think Washington might have blamed the whiskey on his loss, but quite the opposite: Washington became increasingly convinced that whiskey was an imperative resource for a successful army.

After the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, with Boston and New York in British control, Washington found himself entrenched in a long struggle. Two years in, he wrote to William Buchanan, who was in charge of army supplies:

It is necessary, there should always be a Sufficient Quantity of Spirits with the Army, to furnish moderate supplies to the Troops. In many instances, such as when they are marching in hot or Cold weather, in Camp in Wet, on fatigue or in Working Parties, it is so essential, that it is not to be dispensed with. I should be happy if the exorbitant price, to which it has risen, could be reduced.

Washington also proposed the erection of public distilleries to keep the price of liquor steady, so that armies might not be reliant on imports. This idea never gained traction, though what a different country we might be living in if it had.

After the war, Washington and his fellow founders were left to figure out how to structure the country, pay for the services it would provide, and deal with Revolutionary War debts, which by 1790 were close to a million dollars. Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton had proposed an excise tax that infuriated distillers on the frontier. When Pennsylvania farmers turned a protest on the distiller’s tax into an open rebellion (see John Neville and James McFarlane, this page), Washington found himself back in the neighborhood of Fort Necessity, though he only marched as far as Cumberland, Maryland, before handing over the army to Light-Horse Harry Lee (father of Confederate general Robert E.) and Alexander Hamilton.

After the rebellion subsided and with his presidency over in 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon and built there what was probably the largest distillery in Virginia. It’s also the most well-documented of any distillery from the eighteenth century in America, and thus provides great insight into distilling technology at the time.

Washington’s farm manager, James Anderson, was a Scottish immigrant who had experience distilling in his home country. In 1797, Anderson urged Washington to let him set up two small stills in the plantation’s cooperage, and the six hundred gallons of whiskey he made that year convinced Washington to commit more seriously to the endeavor.

The new 2,250-square-foot distillery was laid out adjacent to the gristmill and eventually would have five copper stills making as much as eleven thousand gallons of whiskey a year (about the size, measured by output, of Kings County Distillery today, or about a third the size of Jack Daniel’s first distillery). Washington was concerned about the location near the mill, which was some two miles from the Mount Vernon residence, since there were “idlers” who might rob the still, but given the water source, there was no better location. Washington also sought the advice of John Fitzgerald, a rum distiller in Alexandria, as to the potential profit of the enterprise. Fitzgerald advised him that as long as Anderson was up to the task, he should proceed.

Washington’s whiskey was made with 60 percent rye, 35 percent corn, and 5 percent barley that was malted on-site. This makes Washington’s rye whiskey not unlike most made in the United States today, though his was often sold unaged, or lightly aged. The common whiskey was twice distilled and cost about fifty cents a gallon, but more expensive versions were three- and four-times distilled and could cost twice as much. Anderson’s son John lived near the distillery and did some of the distilling, though much of the work was carried out by slaves Hanson, Peter, Nat, Daniel, James, and Timothy. Washington’s distillery also made a small amount of brandy from peaches, apples, and persimmons. Some whiskey was infused with cinnamon. Like many distilleries of the day, the spent grain was useful as feed for Washington’s farm animals, especially pigs. The distillery supported 30 cows and 150 pigs that could, according to Polish visitor Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, “hardly drag their big bellies on the ground.”

Washington himself didn’t drink much in the way of distilled spirits, preferring Madeira and a certain Philadelphia porter made by Robert Hare, which he often requested by special order. Washington had his own beer recipe, so one could imagine him taking a curious interest in the distilling business. But Washington was already an old man when his distillery came along, and though he was generally pleased with its success, he expressed a clear ambivalence in his correspondence on the topic. One guest from this era noted that Washington rarely spoke, though wine seemed to make him more jovial. That may also have been because Washington’s dentures, which were made not of wood but of the teeth of slaves, were so painful that it was easier to be seen and not heard. That is, until alcohol lessened the discomfort.

DISTILLER,

TAX COLLECTOR

1731–1803

![]()

Allegheny Cemetery, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

JAMES MCFARLANE

MILITIA COMMANDER,

REVOLUTIONARY WAR VETERAN

CA. 1751–1794

![]()

Mingo Cemetery, Finleyville, Pennsylvania

The first white men in the West were subject to the same physical conditions as the Red man. Living in the continual damp and shade of the primeval forest, sleeping in part on the ground or near it, exposed to cold and rain as no succeeding generation has been exposed, the western pioneer became remarkably phlegmatic; the blood was cold and slow and the animal spirits consequently in an habitual state of depression bordering on melancholy. The influence of strong drink on these men, as on the savages who craved it so eagerly, was acceptable and exceedingly exhilarating.

—Archer Butler Hulbert, the Ohio River

John Neville’s plantation, Bower Hill, just south of Pittsburgh, would have been an impressive sight to neighbors. At sixty years old, he was appointed revenue collector for four counties in Western Pennsylvania, a job that would earn him a complicated place in history, since Neville was a distiller himself.

He was a military man and knew the West well. He had skirmished in Washington’s command under General Braddock during the Seven Years’ War and had taken Pittsburgh during the Revolutionary War as a militiaman; he then joined the Continental Army, enduring the winter at Valley Forge, and fought in several key battles, including Yorktown. By war’s end he was a brigadier general and had been granted land to settle.

Bower Hill was a ten-thousand-acre operation with fields, outbuildings, barns, and slaves. The two-story home stood out for having clapboard siding, plastered walls and ceilings, and wood floors. Wallpaper and carpets were among the luxuries enjoyed by Neville and his wife, Winifred. Their son, Presley, lived in a brick house down the hill. Other relatives and in-laws held prominent positions in town, and the family business was supplying the military with goods, including whiskey, as it set off on routine missions down the Ohio River into Indian country.

Neville’s plantation stood in stark contrast to his neighbors in the woods of the West, mostly subsistence farmers living in log cabins in the hills and hollows of the Appalachians. To them, Neville represented a kind of eastern elitism they had moved west to avoid.

Back in Philadelphia, Washington worked with his Treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton, a financially savvy politician, to design a tax on distilled spirits to help pay down the war debt. It was also a move to assess a form of taxation in a young nation very opposed to the idea of taxes and duties. Liquor, Hamilton figured, was a luxury, consumed in large quantities in the States, and its production could be organized in a structured way so as to make the tax on producers a routine part of business, and an industrialized distilling trade would function as a revenue arm of the government.

Interestingly, about this time, England banned stills of less than five-hundred-gallon capacity, in effect outlawing the farm distiller and encouraging a commercial scale that could be monitored and taxed with some authority. (If such a tax were enacted today, it would eliminate all but about 5 percent of commercial distilleries and nearly all of the craft distilleries.) Hamilton was watching the English laws from afar and looked to apply the same general principles to an American taxation system. However, though there were plenty of large commercial distilleries in the United States, Hamilton knew he couldn’t ban small-scale distillation without alienating the West, where whiskey was understood to be an extension of agricultural life.

Hamilton devised his law to distinguish between town stills and country stills. The stills set up in cities and towns, which could be monitored, would play a flat tax on volume produced. The country stills, which couldn’t be easily monitored, would pay a tax on the size of the still. Large distillers paid nine cents for every gallon, and eighty-eight cents for every ten gallons, a graduated rate that offered savings if production was large. Hamilton based the system off his observations of the urban distilleries that employed one-hundred-gallon stills or larger and ran them daily during a four-month distilling season.

Hamilton’s math didn’t work for the rural stills, which ran less often and for shorter seasons. Additionally, the tax was due in cash, a significant hardship for the frontier farmer who subsisted mostly on barter. In Western Pennsylvania, whiskey was cash.

Hamilton sent excise inspectors a manual, hydrometers, and certificates they could use to record still capacity and barrels filled, and to gauge the proof of whiskey stored. The inspector was to keep a ledger, and taxed barrels earned a certificate, almost like a deed, so that buyers knew they were getting registered liquor. Neville received an annual salary of $450 plus a 1-percent commission.

Neville’s first hire, Robert Johnson, was to be a deputy in charge of the business. He set about his unpopular task. On a September night in 1791, he encountered a group of twenty men made up in blackface and wearing women’s dresses who were carrying muskets and other weapons. They forced Johnson to undress and applied hot tar to his bare skin. They then threw bushels of poultry feathers on his body, cursed at him, took his horse, and fled. Johnson, covered in rapidly hardening pitch, was left alone in the dark with second-degree burns, scarred for the rest of his days.

Over the next two years, unrest grew to a fever pitch in the forks of the Ohio River region. By 1794, barns were burned merely because distillers had agreed to be registered. A straw effigy of Neville was burned, to the delight of a rowdy crowd. A man tried to attack Neville, his wife, and granddaughter on the road, but Neville was able to wrestle him to the ground and throttle him until he yielded. Liberty poles, once symbols of revolution, now were symbols of rebellion: hoisted with the image of a snake on a banner with the phrase “Don’t tread on me.”

In July 1794, Federal Marshal David Lenox was sent in to serve subpoenas on delinquent distillers. On the fourteenth, Neville and Lenox served William Miller with a fine and a court appearance in Philadelphia. Miller, a war veteran and an honest man, cursed the paperwork, and saw his dreams of a move to Kentucky rapidly fading. Meanwhile, a posse of men gathered in the distance. Shots rang out and Neville, not wanting to engage, was determined to return to his mansion, which had been fortified in anticipation of a siege.

The men rounded up reinforcements and marched to Bower Hill, hoping to take Lenox captive. In the early morning, they found Bower Hill’s windows covered with planks. Neville told the men to stand down, then fired into the crowd, mortally wounding Miller’s nephew. The rebels fired back, forming a line and serving volleys of musket balls into the house. Winifred reloaded Neville’s guns when necessary, and by picking off rebels from a protected vantage point, Neville wounded four more. Neville’s young granddaughter lay on the parlor floor to avoid flying musket balls.

The next day a group of soldiers from Fort Pitt, under Major Abraham Kirkpatrick (Winifred’s brother-in-law), took up positions in Bower Hill. Neville himself hid in a nearby ravine. The rebels, under the name the Mingo Creek Militia, elected James McFarlane as their leader, and took up battle lines below the house.

Women and children were allowed to leave, and shooting commenced. At one point, the rebels saw what they thought was a white flag waving from a window. McFarlane stepped from behind a tree to tell his men to hold fire. At that lull in the action, a shot rang out from the house, and McFarlane fell dead. The rebels were incensed. They burned the house, captured Kirkpatrick, Presley Neville, and Lenox, but each managed to escape that evening.

Still, the conflict succeeded at escalating the fight over Hamilton’s excise tax. With men killed, the Mingo Creek Militia rallied against Washington and earned sympathy on the frontier. Facing a crisis, Washington called up a militia of thirteen thousand men, and led troops for some of the march to Pittsburgh. It was such a serious show of force that the Mingo Creek Militia backed off and a crisis was mostly averted. But still, McFarlane was given a hero’s funeral, and the excise tax was repealed seven years later. Neville moved in with his son, a short distance away from his original home. The house still stands and can be visited today. The site of Bower Hill is the parking lot to a Catholic church.

A TOUR OF SOUTHWESTERN PENNSYLVANIA

![]()

THE AREA AROUND PITTSBURGH is home to the early history of whiskey in the United States, especially the Whiskey Rebellion, which lasted for two years and culiminated with George Washington’s calling in the militia to enforce the position of the federal government. Several rye whiskey distilleries were also located in the region.

1. WHISKEY POINT

Whiskey Rebels gathered here to resolve their grievances

2. JAMES MCFARLANE

Leader of the Whiskey Rebels, shot at Bower Hill, is buried in Mingo Cemetery near Fayetteville

3. WOODVILLE PLANTATION

Site of Presley Neville’s house, his father would move in after the Battle of Bower Hill and build this home, which still stands and is open to visitors

4. BOWER HILL

Site of critical siege on John Neville’s house in 1794, flash point of Whiskey Rebellion

5. WIGLE WHISKEY

A modern craft distillery is here in downtown Pittsburgh, named after Phillip Wigle, one of two Whiskey Rebels to be convicted. Washington later pardoned him

6. JOHN NEVILLE

Loathed tax collector and nemesis of Whiskey Rebels is buried in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh

7. HENRY CLAY FRICK

Distiller and industrialist is buried in Homewood Cemetery

8. BRADDOCK’S FIELD

About 6,000 protestors gathered here to argue for secession and plot a raid on Pittsburgh

9. POSSUM HOLLOW DISTILLERY

Possum Hollow was a successful pre-Prohibition brand of rye whiskey, based in McKeesport

10. JOHNSTOWN FLOOD

A short drive will take you to Johnstown Flood National Memorial, where the dam at Henry Clay Frick’s private hunting club failed in 1889 and killed 2,209 people

11. WEST OVERTON DISTILLERY

Abraham Overholt built his first modern distillery at this site, also the family farm

12. OLD OVERHOLT DISTILLERY

Site of modern distillery, now defunct, at Broad Ford

13. FORT NECESSITY

Washington’s only surrender came when his troops were out of provisions and had only whiskey