On October 6, 1775, forty-one-year-old Captain Henry Mowat sailed out of the Boston harbor aboard the armed ship Canceaux. Mowat was commanding a mini-squadron of Royal Navy vessels—his own ship, carrying eight guns; the Halifax, a schooner with six guns; and two armed transports ferrying some one hundred soldiers. Their mission: to discipline and punish nine coastal towns in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine by shelling the settlements and destroying vessels in their harbors. Those seaports were hotbeds of colonial resistance and sheltered rebel privateers. It had taken three months for the Admiralty’s harsh instructions to reach Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, the commander of Britain’s American squadron. His new orders empowered Graves to warn coastal towns to cease immediately any violent actions against Loyalists and British officials. If they failed to comply, Graves was to “proceed, by the most vigorous efforts, against the said Town, as in open Rebellion against the King.”1

Graves had long wanted to chastise the seaports he knew were home to the American privateers insulting his ships. As tensions escalated, Graves had witnessed “the King’s people killed and made prisoners, lighthouses destroyed, commerce interrupted, and the preparations for war daily making in the different towns.” It was high time that he neutralize expendable seaports across New England. But dispatching Mowat to execute the Admiralty orders would likely carry a steep human cost—and significant political and moral consequences.2

When he was advised that his initial target, Cape Ann, Massachusetts, could not be bombarded effectively, Mowat instead took course for Falmouth (modern Portland, Maine). A successful lumber-trade port with a population of some 2,000, Falmouth had a deep and broad harbor that would allow his ships to shell the two- and three-story wooden buildings along the hillside at close range. The town also had a history of militant rebelliousness dating back to the mid-1760s, when the locals had burned stamped papers, attacked customs officials, and boycotted East India tea. Rebels there had even briefly held Mowat captive in spring 1775. For Mowat, strategic advantage and an opportunity for personal revenge coincided perfectly at Falmouth.

Mowat anchored offshore in the afternoon of October 16 and sent his ranking officer to address the population gathered in the local meetinghouse. Since the inhabitants had “been guilty of the most unpardonable Rebellion,” the proclamation read, the king’s ships would now “execute a just Punishment.” Mowat would grant the locals a brief moratorium to evacuate before the bombardment commenced. As the warning sank in, a “frightful consternation ran through the assembly, every heart was seized with terror, every countenance changed color, and a profound silence ensued for several moments.” Residents had only partially evacuated the town when at 9:40 the next morning the Royal Navy demonstrated what havoc even two small ships could wreak.3

“Never was there a fairer autumnal day,” recollected one witness; “the sky was cloudless; the wind gentle; the atmosphere invigorating.” Into this idyllic New England scene, “a shower of cannon-balls, carcasses, bombs, live shells, grape-shot, and even bullets from small-arms, was raining down upon the compact part of the town.” Our onlooker experienced the bombardment as sublime, a terrible spectacle that would have been fascinating “but for the wanton destruction the missiles immediately wrought. They crashed through the warehouses, they plowed up the streets, they cut off the limbs of the trees, they sank the shipping, they set fire to the dwellings.” To witnesses, these inanimate agents of destruction seemed diabolical as they “screamed and hissed, they whirled and danced, they shrieked and sung, like so many demons rejoicing over the havoc they were making.” Evacuees who were still in the town found that the oxen pulling the carts with their belongings were so “terrified by the smoak and report of the guns” that they “ran with precipitation over the rocks, dashing every thing in pieces, and scattering large quantities of goods about the streets.” Seeing that buildings towards the southern part of the town failed to catch fire, Mowat sent landing parties to set alight wharfs and storehouses. The flames kept spreading, fanned by the early afternoon breeze. A Mrs. Barton, whose husband had enlisted with the Continental Army, was home alone with their young son, when “the hot shot and shells began to fall near, and several of the neighboring buildings were on fire.” Gathering just a few pieces of clothing, she and the boy evacuated a mile away, braving what must have felt like an endless obstacle course; several times, bombs with still-smoking fuses fell near her.4

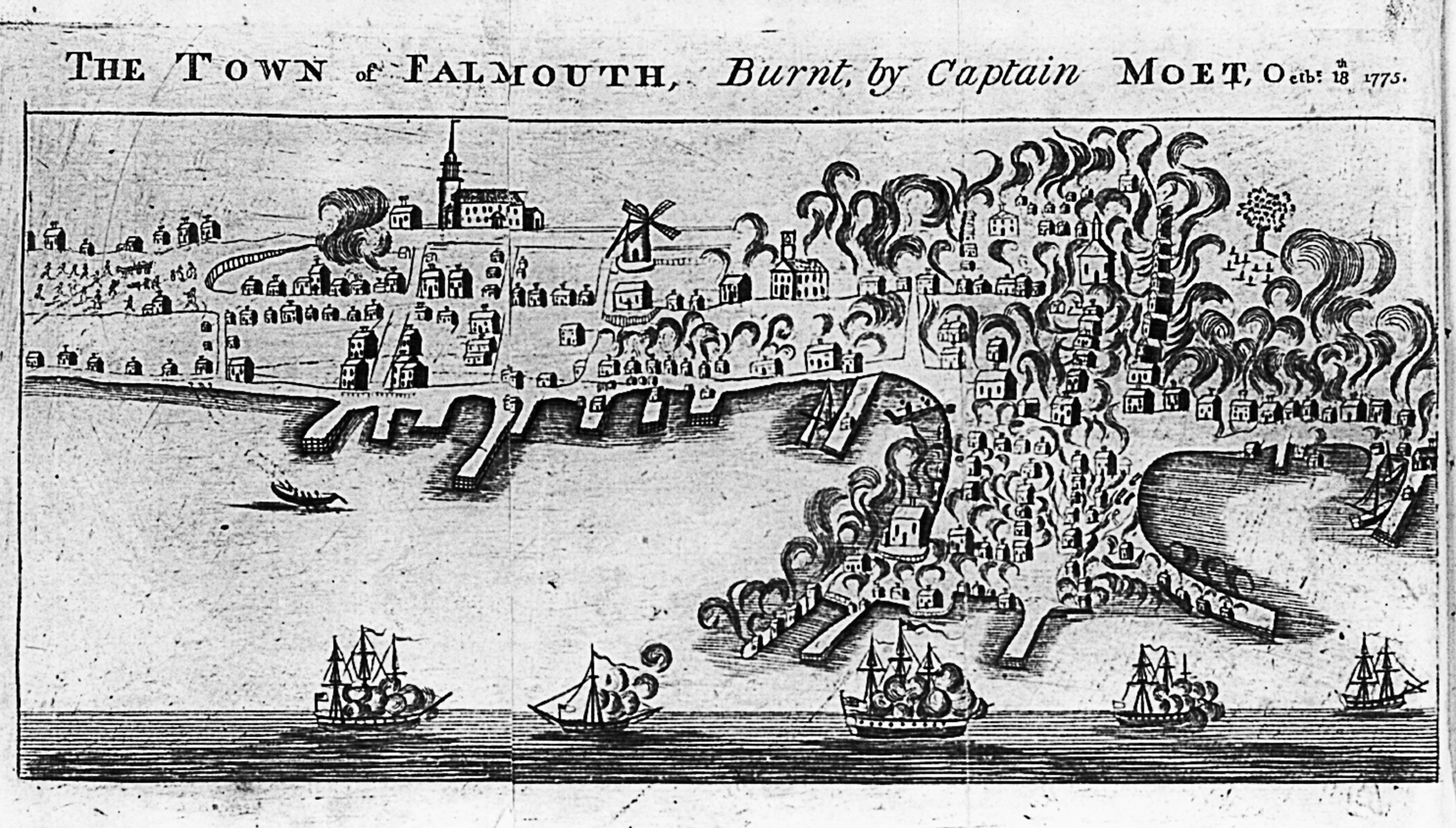

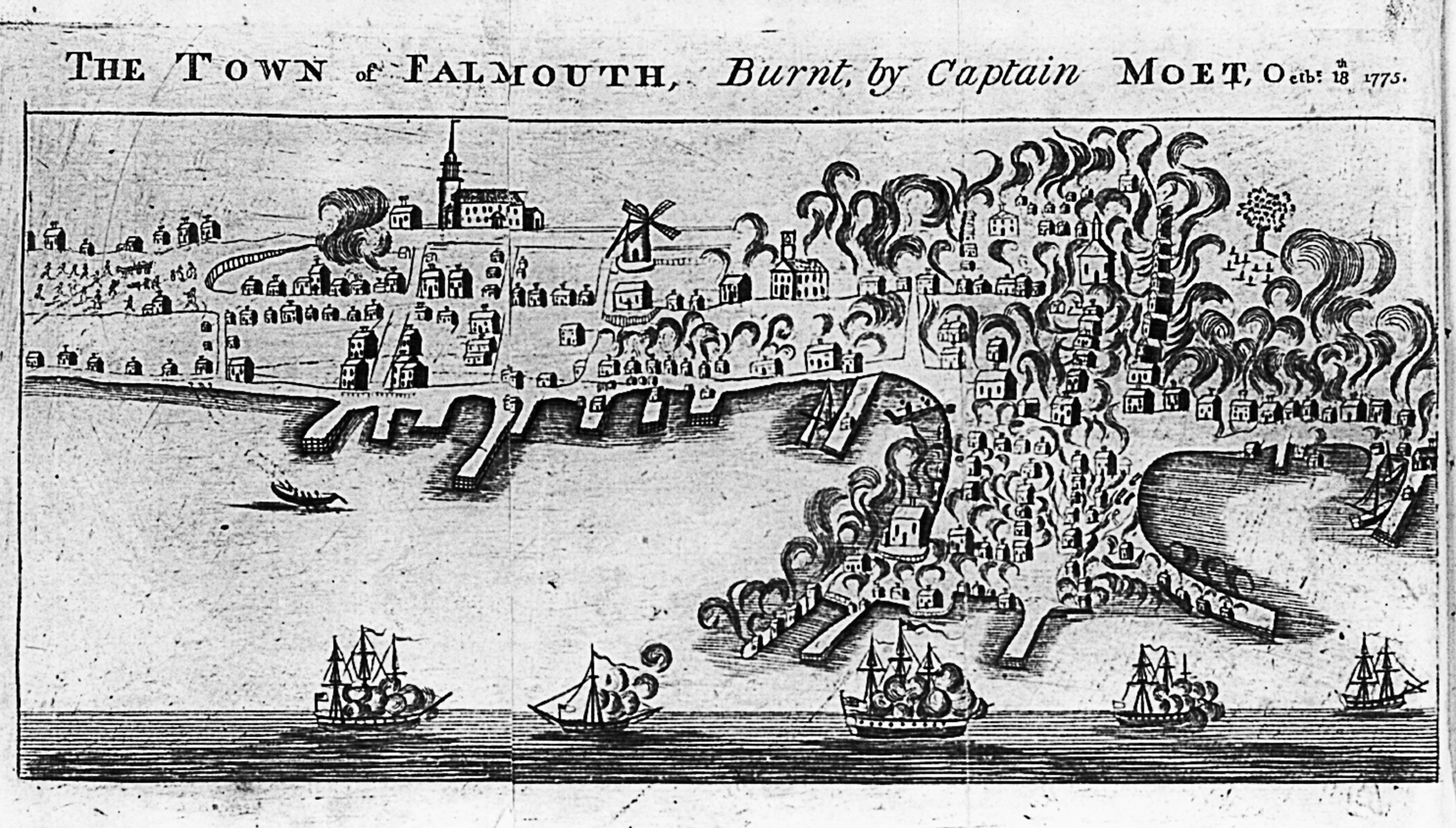

John Norman, The Town of Falmouth, Burnt by Captain Moet, Octbr. 18th 1775 (Boston, 1782). In a punitive mission in fall 1775, the Royal Navy destroyed large parts of modern Portland, Maine. This fairly crude but effective engraving was published as the frontispiece to an early history of the war when America had all but won the conflict. A bird’s-eye view of the bombardment, it remembers Britain’s early warfare of desolation that fueled the ire of war critics on both sides of the Atlantic. Credit 18

Even as the attack was under way, Patriot militias from nearby Brunswick and Scarborough were slipping into Falmouth. Envious of the town’s commercial wealth, and frustrated by its mixed politics, the militias looted the property of suspected Loyalists. And although Graves had reassured the Admiralty that he had ordered Mowat to “protect the persons and property” of Loyalists, British shells did not discriminate between Patriot and Loyalist targets.5

During nine hours of pandemonium, more than 3,000 projectiles hit Falmouth, one every eleven seconds. Eleven ships were destroyed; Mowat captured an additional four in the harbor. The day after, the log of the attacking ship Canceaux noted that fires continued to burn in the town. When it was all over, roughly three-quarters of the buildings lay in ashes—including the Episcopal church, the new courthouse, the old meetinghouse, the distillery, most wharves, almost every store—and some 160 families would begin the winter without shelter.6

Rumors flew of similar squadrons setting a course for towns up and down the New England coast. Benjamin Franklin considered safeguarding his writings and accounts and suggested that his daughter evacuate her family even from faraway Philadelphia. But before the Royal Navy could destroy any more towns, Britain’s escalation of violence produced an immediate backlash, both in America and at home. The American Patriot press denounced Mowat as a monster. Falmouth bolstered the case for independence a full nine months before that notion became a reality. “The savage and brutal barbarity of our enemies in burning Falmouth,” wrote the New-England Chronicle as early as October 19, proved that Britain was “fully determined with fire and sword, to butcher and destroy, beggar and enslave the whole American people. Therefore we expect soon to break off all kinds of connection with Britain, and form into a Grand Republic of the American Colonies.” News of the highly localized attack spread fast and far. John Adams, then at the Congress in Philadelphia, received numerous letters whose authors interpreted the destruction of Falmouth as a declaration of war, or at least as a clear indication of the malicious intent of the “British barbarians.”7

One man who took a special interest in the events at Falmouth was General George Washington. Just four months earlier, the Continental Congress had elected the delegate from Virginia as commander in chief of all American forces. Washington, who always claimed he had not sought the appointment, was a natural choice: few colonial men possessed his military experience or his reputation for skill and courage in the field. A key political reason for his selection was that a Southerner was needed to “nationalize” America’s struggle, given New England’s disproportionate influence in the early days of the rebellion. Washington’s character and his personal values were crucial, too: contemporaries described him as temperate, earnest, and prudent, with a commanding and dignified presence. Washington embodied what John Adams called the “great, manly, warlike virtues.” “There is not a king in Europe,” said Dr. Benjamin Rush, a future signatory to the Declaration of Independence, “that would not look like a valet de chamber by his side.”8

Charles Willson Peale, George Washington (1776). John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress, commissioned this portrait of Washington as commander in chief. One of the most politically engaged artists of his generation, in 1776 Peale enrolled in the Pennsylvania militia; the following year he was at the Battle of Princeton. During the Revolution, Peale served on thirty committees, as agent for confiscated Loyalist estates in Philadelphia, and as a representative in the state legislature. When Martha Washington asked Peale to paint her a miniature of her husband, he modeled it on this portrait. Credit 19

Congress had instructed Washington to “regulate your conduct in every respect by the rules and discipline of war.” When he was now briefed about Falmouth at the Cambridge headquarters of his Continental Army, Washington condemned the “Outrage exceeding in Barbarity & Cruelty every hostile Act practised among civilized Nations.” And if other public and private correspondence is any indication, the attack appears to have helped steel the rebels’ resolve. It injected new urgency into their struggle and infused it with political and indeed spiritual meaning: “[T]he unheard of cruelties of the enemy have so effectually united us,” wrote one man, “that I believe there are not four persons now in [P]ortsmouth who do not justify the measures pursuing in opposition to the Tyranny of Great Britain.” Imperial violence, far from terrifying rebellious colonials into submission, seemed instead to fan the flames of insurrection.9

The government’s outspoken critics in Britain understood as much. One of the most prescient was Edmund Burke, MP, whose towering intellect and soaring rhetoric made for many a memorable hour in the House of Commons. In a famous speech advocating reconciliation with the colonies that he had given in March 1775, the Irish-born Burke explained why any policy of coercion must necessarily fail in America—in part because the colonists were descendants of freedom-loving Protestant Englishmen and in part due to their sheer distance from central government. But all of Burke’s cogent reasoning could not slow the momentum. By the fall, Burke turned his attention to the dangers of what was then called desolation warfare—punitive raids against vulnerable military targets, civilians, and property that were designed to shock the enemy into compliance. To hard-liners, desolation warfare was a necessary answer to rebellion. But Burke doubted the rationale of such an approach: at best, “the predatory, or war by distress” might irritate one’s opponents, but it could never entice them to accept the aggressor’s rule over them. Burke was adamant that the strategy would only strengthen the resolve of the colonists and prolong the conflict.10

What Burke and his fellow MPs could not yet know was that the war of desolation was already well under way across the Atlantic. Once news of the bombardment broke, responses both at home and overseas vindicated Burke’s analysis. Skeptical newspapers in Britain warned that the “coercive and sanguinary Measures pursued against the Americans…will produce nothing but the bitter Fruit of Ruin, Misery, and Devastation.” Writing under the nom de guerre “Nauticus,” one author accused Lord Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, of frivolously ordering the horrendous burning of Falmouth. “[S]porting with the Miseries of Mankind,” he had waited for the onset of winter, so that the displaced “aged Parent and the helpless Child were to be exposed to the Severity of the Frosts.” The burning of Falmouth became a cause célèbre for American Patriots and for British conciliators. The foreign secretary of Britain’s archenemy, France, rather like Edmund Burke, was more farsighted than many British leaders when he characterized the events at Falmouth as an “absurd as well as barbaric procedure on the part of an enlightened and civilized nation.” Falmouth seemed, indeed, a British public relations disaster of the first order.11

After the naval shelling, many of the king’s loyal subjects left Falmouth for Britain, Halifax, or Boston, although they would be forced to relocate once again when the British withdrew from that town the following spring. Not long after Falmouth, Admiral Graves was replaced amid allegations of corruption and incompetence. He remained adamant, though, that—since leniency towards those ungrateful rebels had only encouraged “farther Violences”—they must “be severely dealt with.” And already another imperial commander was preparing to lay waste to the largest city in the largest American colony. Only this time the British compounded, in the rebels’ eyes, their criminal escalation of violence by arming runaway slaves. The British initiative, and the cunning American response, would change the trajectory of the conflict: it proved a turning point in public opinion that helped solidify the Patriots’ resolve.12

Flaming Arguments

On the eve of the Revolution, Norfolk, Virginia, was a flourishing coastal town of some 6,000 inhabitants. A key hub in the transatlantic trade network, it also served as a regional shipbuilding center. Many of Norfolk’s Scottish-born tobacco merchants enjoyed close links with native Virginia merchants and planters. When the Continental Association was introduced in 1774, however, most of its documented local violators were Scots, who in due course became avowed Loyalists; most native Virginians complied with the insurgents’ new regime.13

Like other British leaders during the American crisis, Virginia’s governor, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, had previous experience with rebellion: his father had supported the doomed Jacobite rising of 1745, taking his young son with him on campaign. It had only been through John’s uncle’s connections at George II’s court that his father’s sentence was commuted from death to lifelong house arrest.14

On April 20, 1775, as British troops to the north regrouped after Lexington and Concord, Dunmore ordered marines to remove the gunpowder from Virginia’s public magazine in Williamsburg. White slaveholders were particularly anxious about the threat of slave revolts at the time, and seeing their defensive capabilities eroded made them feel vulnerable. As the conflict with local rebels escalated, Dunmore feared for his life and he evacuated his family to Scotland. By June, he had fled his impressive palace, installing himself at a makeshift military headquarters on board a flotilla off Norfolk just before rebels pillaged his official residence.15

In October, Dunmore’s raiding parties seized rebel weapons in Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties. Patriot leaders now openly discussed their options: Should they fortify Norfolk against British aggression, or should they demolish it to deny the British access to a Loyalist stronghold, with its valuable garrison and trading base? Adapting the Roman senator Cato’s dictum, Thomas Jefferson recommended the latter course: “Delenda est Norfolk”—Norfolk must be destroyed! Some members of the local committee of safety agreed, as did the top military commanders for the region, the Virginian colonel William Woodford and his senior colleague, Colonel Robert Howe, the commander of the 2nd North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army. But Revolutionary Virginia’s civilian leaders kept procrastinating over Norfolk’s fate. Meanwhile, many of the town’s inhabitants from across the political spectrum began to seek refuge in surrounding areas.16

Sir Joshua Reynolds, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore (1765). Dunmore’s family was deeply implicated in the British Empire’s history of rebellion and counterinsurgency, from the Scottish Highlands to the Virginia tidewater. In this painting by the preeminent portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, Dunmore—sporting a tartan jacket and kilt—is striding into the wind, leaving behind a tree trunk symbolizing perhaps the devastated Highlands of his youth. In his future lay the governorships of New York and Virginia, a war against the Shawnee in a campaign to open up the western lands, and the emancipation of rebel slaves to buttress the Crown’s cause in Revolutionary America. Credit 20

Since the spring, rumors had been circulating that the British government was considering arming slaves or inciting insurrection. Slaves repeatedly petitioned General Gage in Boston for their freedom in return for military service. General Burgoyne suggested to George III that Native Americans in the North could help move arms to Southern slaves. And Secretary Germain received a proposal that Lord Dunmore raise “the bravest & most ingenious of the Black Slaves, whom he may find all over the Bay of Chesapeak,” for unlike “African[s] born black in the West Indies,…the meanest of Mankind,” those born in Virginia or Maryland were “full of Intelligence & Courage.” In South Carolina, the jittery white ruling elite ordered Thomas Jeremiah, a free black fisherman and pilot, hanged and burned for allegedly intending to help the British. A slave known as George was executed for preaching that “the Young King” would “set the Negroes Free.” To South Carolina governor Lord William Campbell, their executions amounted to judicial murder committed by “a set of barbarians who are worse than the most cruel savages any history has described.” Meanwhile, plantation owners in the Carolinas and Virginia strengthened their slave patrols to control the movement of slaves beyond the plantations.17

Dunmore initially rebuffed runaway slaves seeking his protection. But since he had previously raised the possibility of emancipating slaves, Southern slaveholders remained suspicious of his intentions. Meanwhile, William Henry Lyttelton, an ex-governor, successively, of South Carolina and Jamaica, had proposed in the British House of Commons that the Crown should actively encourage slave insurrections. A majority opposed his ideas as “horrid and wicked,” but it must have unnerved Southern plantation owners to learn that over a quarter of the House of Commons did in fact side with Lyttelton. For slaves, their masters’ anxiety translated into terror. Among the first slaves who risked running away to Dunmore in 1775 was a fifteen-year-old girl, caught before she reached the governor’s base; her punishment consisted of eighty lashes with the whip, “followed by hot embers poured on her lacerated back,” her treatment clearly intended to intimidate others who might be considering escape.18

Many enslaved people, including Thomas Jeremiah and George, seemed to believe that the purpose of a British invasion of the Southern colonies would be to liberate the region’s slaves. But even though the British never tired of highlighting the hypocrisy of rebels talking the language of liberty while owning slaves, for the British, arming slaves was ultimately a question of military manpower. Enlisting sufficient troops, especially at the start of wars, was a recurring challenge for Britain’s formidable war-waging machine. Indeed, from his vantage point as commander in chief watching developments from the heart of insurgent New England, General Gage had no doubt that Britain now needed to recruit soldiers wherever it could find them. In addition to arming black men, Gage urged hiring auxiliary troops in Europe. He also suggested shipping spare weapons to equip the American Loyalists, a strategy that over the course of the war would become increasingly important.19

By November 1775, Dunmore had been without instructions from London for several months. Sensing he could wait no longer, he issued an emancipation proclamation, promising to set “all indented Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free, that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His Majesty’s Troops.” The British Empire had occasionally armed black slaves, especially in the Caribbean, and sometimes granted freedom to particularly meritorious black soldiers. Dunmore’s decree went further, promising an entire group of slaves freedom in exchange for their military service. While the proclamation applied only to male slaves of Patriot owners who were fit to serve, in practice Dunmore armed the slaves of some Loyalists, too; he also sheltered black women, children, and elderly men.20

Dunmore’s dramatic action was motivated more by military strategy than by humanitarian concerns. Though largely intended to boost manpower, emancipation was also, in the words of one historian, “conceived, perhaps unwisely, as an instrument of intimidation.” It did confirm slaveholding Patriots’ worst fears. “Hell itself could not have vomited anything more black than this design of emancipating our slaves,” commented one observer in Philadelphia to a friend overseas. At the same time, Patriots, in both their public utterances and their private musings, noted that Dunmore’s proclamation had a mobilizing and unifying effect. It reaffirmed rebels in their stance and turned, or so at least they hoped, neutrals and even Loyalists against the governor, king, and Empire. As one scholar of African-American history has written, “Dunmore’s proclamation probably did more than any other British measure to spur uncommitted Americans into the camp of rebellion.”21

By early December, some eight hundred male slaves, traveling primarily by canoe or boat from the Chesapeake and tidewater Virginia—as well as from the Carolinas, Georgia, and Maryland, and as far as New York—had eluded the Patriots’ redoubled patrols and defied their threats of punitive hard labor in lead mines, retribution against family members, or even death. And then there were the women and children arriving with the male escapees. Slaves “flock to him in abundance,” panicking Patriots whispered, arriving in “boatloads” at that “monster,” “Our Devil Dunmore.” Unrecorded scores more tried but failed to reach Dunmore’s waterborne safe haven. Dunmore organized some three hundred black men in the so-called Ethiopian Regiment; their uniform was to display the motto “Liberty to Slaves.” Others worked as pilots, diggers, foragers, or spies, and their wives as laundresses, cooks, nurses, or servants to officers. Patriots meanwhile seized and auctioned off the majority of Dunmore’s own slaves, whom the governor had left behind at his residence.22

Having thrown down the gauntlet of slave emancipation, Dunmore raised the royal banner in Norfolk. He demanded that each white man swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown and wear a red strip of cloth as a badge of loyalty. No sooner were Dunmore and the Loyalists back in charge in Norfolk than Patriot militia routed a force of some six hundred British regulars, Loyalists, and ex-slaves at Great Bridge, the southern land approach to the town, on December 9. Dunmore’s beaten men retreated to his floating base; the Virginia Patriot troops retook Norfolk. Among the wounded soldiers they captured were two former slaves, James Anderson, his “Bones shattered and flesh much torn” in his forearm, and Caesar, who had been hit “in the Thigh, by a Ball, and 5 shot—one lodged.” Any armed slaves who asked pardon from the Patriots were jailed, appraised for their value as property, and shipped off to a life of bondage in the West Indies or Honduras.23

By year’s end, Norfolk’s political fault lines were drawn. During the preceding months, as the area kept changing hands, threats and arrests by both sides had driven an ever-deeper wedge through the community. Most Scottish merchants now evacuated their families and movable goods to Dunmore’s provisional headquarters, which had grown to one hundred vessels, thus leaving their houses and estates exposed to the rebels’ designs. With Dunmore were perhaps 1,000 white local residents, between 1,000 and 1,500 runaway slaves, some 140 British military personnel, and a motley crew of European, Caribbean, and African sailors and civilians. The rebels imposed a cordon to control the flow of people and goods in and out of Norfolk.24

To provision his floating town, Dunmore oversaw land raids and the capture of enemy vessels. When Loyalists on his ships asked permission to go ashore to fetch fresh food and water, the Patriots laid down unacceptable conditions: women and children would have to remain in town; men would be arrested and tried. With local Patriots regularly taking potshots at Dunmore’s flotilla, his men became resentful and restless. “I hope,” wrote one unidentified “gentleman” aboard Dunmore’s flagship on Christmas Day, “the time will soon arrive, when these rebellious Savages will be severely punished for their crimes.” The 2,000 or so Loyalists of that region, he added with concern, “they treat with the greatest cruelty.” He speculated that the British warships were on the brink of destroying the town.25

On New Year’s Day 1776, Patriot troops openly defied British warnings by parading in the Norfolk streets in full view of the fleet. Dunmore’s officers could take no more. Around 3:15 in the afternoon, the British ships opened fire on the town from more than one hundred cannons—not without first giving notice, Dunmore stressed later, so that women and children could be evacuated. Meanwhile, Dunmore sent landing parties to set fire to wharfs and buildings near the waterfront in order to deny cover to American riflemen who had been harassing the vessels. Fires spread rapidly among the mostly wooden houses. One British officer writing from offshore relished the devastation: “It is glorious to see the blaze of the town and shipping. I exult in the carnage of these rebels.”26

Many aboard the British ships might not have been aware that during their bombardment Patriot troops slipped into Norfolk, where they plundered warehouses, looted private homes, and burned numerous structures. Thomas Newton saw his two elegant mansions, nine tenements, ten warehouses, and one shop go up in flames. The Patriot colonel Robert Howe seemed to let the marauders roam freely. And even when he received reports that Patriot properties, such as Newton’s, were being destroyed alongside those of Loyalists, he chose not to intervene.

When it was all over, Colonel Howe sent a report to the president of the Virginia Convention. He had seen “women and children running through a crowd of shot to get out of the town, some of them with children at their breasts; a few have, I fear, been killed.” But despite such a heavy barrage, “we have not one man killed, and but a few wounded.” What Howe failed to reveal was that most of the physical destruction of Norfolk had in fact been caused not by British cannons but instead by those Patriot troops who had looted and burned houses under the cover of what turned out to be an only moderately effective bombardment from sea. Afterward, Howe and Woodford concealed the Patriot troops’ actions and their own complicity. “The wind,” they told their civilian superiors, “favoured their [the Britons’] design, and we believe the flames will become general.”27

Accepting the Patriots’ challenge in the realm of polemics, Dunmore issued his own version of events from his shipboard printing press. Using meteorological arguments, just as the Patriots had done, Dunmore blamed most of the destruction on the rebels:

As the wind was moderate, and from the shore, it was judged with certainty that the destruction would end with that part of the town next the water, which the King’s ships meant only should be fired; but the Rebels cruelly and unnecessarily completed the destruction of the whole town, by setting fire to the houses in the streets back, which were before safe from the flames.28

Perplexed by the conflicting reports, the committee of safety conducted an inquiry. Alas, no depositions have ever been found—the man in charge of the investigation was none other than Colonel Howe. What we do know is that after the initial bombardment by Dunmore’s ships, the Convention ordered the evacuation of the remaining population of Norfolk. It then secretly authorized the destruction of what was left of the town, as well as the demolition of nearby Portsmouth, should military commanders consider such action advisable. In early February, Howe did indeed raze Norfolk’s remaining 416 structures: “We have removed from Norfolk, thank God for that! It is entirely destroyed; thank God for that also.”29

Meanwhile, as Dunmore departed for New York City, he abandoned some 1,000 dead or dying African-Americans ravaged by smallpox and other epidemics, leaving stretches of the Virginia coast “full of Dead Bodies, chiefly negroes.” Patriots also accused him of having sent infected black men ashore as a cynical farewell gesture.30

In 1777, Virginia legislators would revisit the unresolved issue of which side had caused precisely what amount of destruction. An investigatory committee painstakingly gathered depositions and professional valuations of destroyed properties. The official report concluded that “very few of the houses were destroyed by the enemy”; indeed, most houses that were set on fire could have been saved. Instead, the Patriot soldiers “most wantonly set fire to the greater part of the houses within the town, where the enemy never attempted to approach, and where it would have been impossible for them to have penetrated.” In total, American troops devastated some 863 structures worth over £110,000. The British destroyed 54 buildings and personal property valued at barely over £5,000. In other words, the British were responsible for less than 6 percent of destroyed buildings and 4.3 percent of the value of total losses. The Revolutionaries suppressed this inconvenient report for the duration of the war; it was in fact first published in 1836. The Patriots thus not only achieved their initial objective of denying the British a valuable coastal base while punishing the local Loyalists; they also managed to lay the blame entirely at the feet of the British.31

In early 1776, Patriots saw that Norfolk’s burning could be used to rally public opinion behind the American cause—and they seized the opportunity. It did not hurt that it followed hard on the heels of Falmouth’s destruction. Samuel Adams felt that the attack did more to help people make up their minds to support the Revolution than “a long Train of Reasoning.” For John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress, the attack confirmed that Britain was opting for brutality, with evidence of “inhumanity so contrary to the rules of war and so long exploded by all civilized nations.” The rebels were fast occupying the moral high ground: they claimed European-style codes of war as their ethical baseline while accusing the British of violating those codes. At the same time, they played the registers of psychological and propaganda warfare with a virtuosic flourish. The recipient of Hancock’s letter, George Washington, hoped that Falmouth’s and Norfolk’s destruction, and similar threats to other towns, would “unite the whole Country…against a Nation which seems to be lost to every sense of Virtue, and those feelings which distinguish a Civilized People from the most barbarous Savages. A few more of such flaming Arguments” would encourage Americans to embrace independence. Violence, especially when spun appropriately, had a powerful unifying effect.32

In Britain, those who favored crushing the rebellion took heart that their army and navy would “strike such a terror, into these deluded people.” By contrast, those opposed to escalating the conflict seized on Norfolk to lament the prospect of all-out civil war in the Empire, “attended with circumstances of cruelty, civil rage, and devastation hitherto unprecedented in the annals of mankind.” Making war, emphasized the Duke of Richmond, a prominent opposition peer, “in a manner which would shock the most barbarous nations, by firing their towns, and turning the wretched inhabitants to perish in cold, want, and nakedness,” harmed not just Britain’s enemies: it hurt her loyal subjects, too.33

At Norfolk, then, Dunmore’s decision to escalate the conflict had provided cover for the Patriots to intensify their violent suppression of Loyalist dissent, sacrificing one of America’s flourishing port cities in the process. America’s new leaders, including Adams and Washington, may initially have been unaware of the real agents of destruction. But Howe and Woodford, who successfully hushed up the Patriot troops’ part, could not have hoped for a greater triumph in their war of words. The British dilemma had been thrown into sharp relief. Had the “fire and sword” approach—which had come to haunt the British after Falmouth, and which at Norfolk had given the rebels the perfect excuse for their own tactical unleashing of violence—already discredited itself completely? Or could a persistent application of maximum force still break the back of the rebellion before it gathered irreversible momentum?34

During the spring of 1776, a vast armada assembled off Britain’s coast, poised to launch the largest-scale overseas invasion in European history. Among the tens of thousands of soldiers were not only Britons but large contingents of Germans. For, true to George III’s recent promises, in early 1776 the Crown had signed the first treaties for auxiliary troops with the rulers of Hessen-Kassel, Hessen-Hanau, and Brunswick. Over the course of the war, Britain contracted 36,000 German soldiers. Partly because Hessen-Kassel provided more than half of those troops, German auxiliaries were generally referred to as “the Hessians.” What made the Hessians not just a formidable military force but a potential weapon of terror was precisely what disqualified them in the eyes of conciliators. In America as in Britain, the Hessians were widely considered to be fierce fighters, reared in despotic lands, with no interest in the conflict or true allegiance to Britain. “Foreigners were to slaughter our oppressed Fellow-subjects in America,” complained one British critic, when Englishmen were “too noble, too generous, too brave, too humane, to cut the Throats of Englishmen.” But despite some vocal domestic opposition, the British government’s policy of hiring foreign troops received the customarily strong parliamentary backing, setting in motion the deployment of thousands of Hessians to the colonies. By the second half of the war, such troops would make up one-third of all British-led forces in North America. Their conduct would remain a bone of contention on both sides of the Atlantic.35

While the formidable British fleet was making ready that spring, bad news kept arriving at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Well into 1775, the Revolutionaries had been trying to convince Britain to change political course; for the vast majority of Americans, reconciliation remained preferable to all-out war. Their dispute had been with Parliament and the king’s ministers. As yet, American insurgents were still pledging allegiance to the Crown. But the tide of Anglo-American relations was turning fast. After the king had proclaimed them to be in rebellion, he had ordered all American ports closed, beginning in March 1776. The Royal Navy was authorized to seize any American ships, as well as their crew and cargo, as if they belonged to avowed enemies. Evidence of Britain’s aggression kept amassing: after Lord Dunmore had armed Southern slaves and destroyed Norfolk, the British had defeated an American assault on a stronghold at Quebec led by Benedict Arnold. In May, delegates at the Congress found out that Britain was hiring Hessians, one of the most shocking pieces of evidence yet that their king was abandoning them. John Hancock concluded that “the British Nation have proceeded to the last Extremity.” New Hampshire’s delegate, Josiah Bartlett, was preparing himself for “a severe trial this summer, with Britons, Hessians, Hanoverians, Indians, Negroes, and every other butcher the gracious King of Britain can hire against us.”36

At the same time as the British were escalating the war by shelling coastal towns and mobilizing non-Anglo forces, imperial authority was collapsing throughout the colonies. Patriot committees and militias stepped into the breach, shoring up the defensive posture of their regions. They oversaw the production of saltpeter and bought up gunpowder, lead, ammunition, and arms. They banned the export of items required to put the colonies on a war footing. They blocked waterways against the threat of a British raid or invasion. In the South particularly, they mounted slave patrols and disarmed black men. By June, Congress was busy drafting a treason law and discussing foreign alliances. After America’s internal civil war had been simmering for several years, her declaring independence would trigger a civil war in the British Empire.37

Repeated Injuries and Usurpations

As an elderly man, Dr. Jacob Dunham would remember that he had been about nine years old when the Declaration of Independence arrived in his New Jersey hometown of New Brunswick. It was most likely July 9 or 10, 1776. Dunham’s father, Colonel Azariah Dunham, was an active Patriot—a member of the colony’s committee of safety, the county committee of correspondence, and the local committee of inspection and observation. The county and town committees resolved that the Declaration should be read in Albany Street in front of the White Hall tavern. A Colonel John Neilson was chosen as the reader. Aware of how divided the community was politically, New Brunswick’s Patriots left little to chance. The two committees charged their members with assembling “the staunch friends of independence, so as to overawe any disaffected Tories” and to counteract any design to interrupt the ceremony. As the younger Dunham recalled, those Loyalists were not large in number but included “men of wealth and influence, and were very active.” All in all, “[t]here was great excitement in the town over the news, most of the people rejoicing that we were free and independent, but a few looking very sour over it.” It is striking that Dunham remembered just how contested the local political scene was, and that the Patriots felt the need to orchestrate a positive reception of the declaration. At the birth of the American republic, its viability was far from assured.38

Hamilton, The Manner in which the American Colonies Declared themselves Independant [sic] of the King of England, throughout the different Provinces, on July 4, 1776 [1783]. In this engraving, illustrating a history of England published at the end of the war, a horseman is reading the Declaration of Independence surrounded by a dense group of listeners. On the wall at the left, a notice is being posted, reading “America Independent. 1776.” Credit 21

In New Brunswick and in dozens of communities across Britain’s rebellious colonies that July, sizable crowds gathered in public squares, in front of courthouses, and in churches or town halls. There were civic processions and military parades; bells rang, and preparations were afoot for fireworks, bonfires, and illuminations. Colonel Neilson and his fellow readers in other localities announced that the congressional document their audiences were about to hear was titled the “unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.” Neilson read the preamble, containing the premise of all that was to come: if one people separated from another, it ought to state its reasons for doing so. The second paragraph contains the famous enunciation of self-evident truths: “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”39

The Declaration’s central and longest section was much discussed at the time but is barely remembered by most Americans today. Yet it is this section—an extensive catalogue of King George III’s political crimes—that helps us understand how, in Patriot eyes, it was British violence that justified both independence and the harsh means by which it would be achieved. To introduce this catalogue of grievances, the Declaration asserts that “[t]he history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.” There follows a litany of accusations, starting with twelve counts of the king unduly meddling in colonial affairs by vetoing colonial laws, discouraging immigration, interfering with judicial freedom, opposing resistance to parliamentary authority, and introducing a standing army. In addition, the king had given his assent to parliamentary legislation harming the colonies: trade was cut off; trials were being relocated “beyond the Seas”; the “free System of English Laws” was being abolished “in a neighboring Province” (Quebec); and so on.40

The recitation of grievances climaxed in a section on the king’s aggressively violent acts against the colonies: “He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people,” the Revolutionaries charged. And he was mobilizing all manner of unacceptable, non-Anglo fighting forces:

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

…

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

By now, the crowds listening in America’s town squares could be in little doubt as to who was to blame for imperial oppression: “He has,” “he has,” “he has”—refused, forbidden, obstructed, abdicated, excited, indeed plundered, ravaged, burned, and destroyed.

With his aggressive, unethical conduct, Congress was saying, the king had removed his colonial children “out of his Protection.” George III had “effectively placed the colonies ‘beyond the line’ of civilized practice in warfare” by introducing illegitimate forms of violence. By using this kind of language, the Declaration’s authors were also speaking to a wider international audience. When the king continually refused to listen to their petitions for redress, the Patriots’ final accusation now concluded, it had become clear that such a “Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”41

After these hard-hitting accusations, a penultimate paragraph reminded Americans of their fruitless pleas to the British people. One last time they invoked the historical and affective bonds that were supposed to bind the Anglo community. When their attempts to seek redress failed, the colonials had been left with no choice but to announce their separation. The final section of the Declaration delivers that farewell, declaring “that these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown”; and that they would henceforth enjoy the rights of all legally sovereign states in the community of nations, including the ability to forge commercial alliances, wage war, and declare peace.42

The Declaration circulated in printed form as well. A broadside version was available as early as July 5; newspapers started printing it on the sixth. By the nineteenth it had been reprinted in seven colonies, and by the end of the month it had appeared in more than thirty papers. But it was public readings, like the one that Dunham still remembered nearly six decades later, that evoked the most powerful and immediate responses.43

Across the colonies, American citizens moved to concretize the separation from the former mother country by destroying the visible symbols of monarchy. Crowds removed the royal coats of arms from courthouses, churches, and other public buildings. They tore down images of the king from coffeehouses and taverns. In Dover, Delaware, the president of the committee of safety threw a portrait of George III on a fire: “[T]hus we destroy even the shadow of that King who refused to reign over a free people.” In Huntington, Long Island, an effigy of the king, “with its face black like Dunmore’s Virginia regiment, its head adorned with a wooden crown stuck full of feathers like…Savages,” and its cloak “lined with gunpowder,” was hanged, exploded, and burned. In Lower Manhattan, New Yorkers and Continental soldiers toppled the equestrian statue of George III on the Bowling Green, at the foot of Broadway. They “drove a musket Bullet part of the way” through the statue’s head before carrying it off in a nighttime procession to the tune of the Rogue’s March, typically the musical accompaniment for community punishments such as a tarring and feathering. After Patriots and Loyalists had struggled to take custody of parts of the statue, the Patriots transported large chunks of it to Connecticut, where female volunteers converted them into 42,088 bullets of “melted majesty,” ready to be fired at the king’s troops. Where until recently Americans had been celebrating royal birthdays with parades, toasts, and fireworks, they now expended gunpowder, alcohol, and violent communal energies on rituals renouncing America’s last king—all while George III’s forces were on the verge of launching an invasion.44

A Hesitant Invasion

In March and April 1776, George Washington had moved the bulk of his Continental Army from Boston to New York. The city was the geostrategic key to America and widely expected to be the main target of a British attack: if they held New York City, the British would control one end of the Hudson; with their northern army coming from Canada holding the other, they would be able to sever New England from the remaining colonies. Over recent months, Washington’s soldiers, civilian laborers, and slaves had erected forts, redoubts, and barricades across parts of Manhattan Island and Long Island. As Continental forces cracked down harshly on suspected Loyalists and waverers, thousands of New Yorkers fled the city; the prewar population of 25,000 dropped to just 5,000 in September 1776.45

On June 29, General Sir William Howe’s invasion armada—110 ships carrying 9,000 troops—had first been spotted off New York. To one rebel lookout it seemed like a “wood of pine trees trimmed,” and, indeed, as if “all of London was afloat.” By July 2, the British were landing on Staten Island. In an exquisite piece of dramatic timing, it was the very same day that the Continental Congress in Philadelphia had voted to dissolve the connection with the mother country. Over the following weeks, as word of the Declaration of Independence spread across the colonies, Howe staged his massive force in preparation for the invasion of New York.46

The fall campaign of 1776 perfectly reflects Britain’s ongoing strategic and moral dilemma. Howe planned to seize New York City, capture the Hudson corridor, occupy Rhode Island, and sweep all of New Jersey. He would offer amnesty to any moderate colonials swearing allegiance to the king. The historian David Hackett Fischer judges it a plausible and humane plan that combined a show of force with conciliatory gestures, all with a view to restoring imperial harmony. But what Howe didn’t know was that his brother Richard, the admiral, was en route from England with a different mission for them both: not only were they to lead the war against the rebels, but they were also to act as a two-man peace commission charged with brokering a negotiated settlement.47

Richard Howe, who had been appointed commander in chief of naval forces in America in January 1776, had apparently made his acceptance of the war mission contingent on his also being named the head of Lord North’s peace commission. Eventually the Howe brothers became the sole commissioners, as North insisted, but Lord Germain limited their remit: they could grant pardons but could not make any substantive concessions to the rebels; surrender was a nonnegotiable prerequisite of any negotiations. But any British diplomatic initiative was running out of time: when Admiral Howe finally departed for America, the Congress in Philadelphia had already begun moving towards independence.48

Admiral Howe’s military orders were to pursue an aggressive war by supporting the army led by his brother William and blockading the North American coast to cut off the rebels’ war supplies. The admiral’s fleet arrived off New York on July 12: 10 large warships and 20 frigates leading some 150 ships manned by roughly 10,000 sailors and transporting 11,000 troops. They would join William Howe’s 9,000-man army on Staten Island, where one officer acknowledged that local Loyalists had already suffered much. Now, finally, their protectors had arrived.49

And more were on the way. The first German troops contracted by the Crown soon landed in America. After an unusually long Atlantic crossing, the Hessians were exhausted, with many suffering from scurvy and contagious fevers. To speed their recovery, Howe gave them excellent campsites on Staten Island, where the Germans appreciated the “beautiful forests composed mostly of a kind of fir-tree, the odor of which can be inhaled at a distance of two miles from land.” Over the following weeks, British and German troops kept arriving, bringing the total number of troops to some 32,000—the largest invasion force seen in the eighteenth century. More than 400 British ships of varying sizes were controlling the waters around New York—and whoever commanded the waterways would eventually hold the city. But instead of launching the offensive as soon as all his assets were in place, William Howe allowed his brother Richard to persuade him to prioritize conciliation. This two-pronged and hesitant approach characterized the remainder of the 1776 campaign. Arguably, it would cost Britain thirteen colonies.50

Admiral Howe’s initial attempts to negotiate with Washington foundered on diplomatic protocol and the sheer incompatibility of their positions. The American commander refused to accept letters addressed first to George Washington, Esq., and then to George Washington, Esq., etc., etc.—he was General Washington, his staff insisted. Quite apart from the fact that the British only had a pardon to offer, when “[t]hose who have committed no fault want no pardon,” Washington made it clear that he was, in any case, not authorized to negotiate. Their peace overtures overtaken by the momentum of American independence, the Howe brothers now pivoted to their military mission.51

The plan for the opening moves of the campaign had been designed by General Henry Clinton. As the third of the major generals appointed by George III in February 1775, Clinton was subordinate to both Howe and Burgoyne. He had just returned from a disastrous Southern mission to Charleston, South Carolina: British forces had had to abort a naval bombardment, amphibious landings, and a ground assault in the face of unfavorable topography, poor coordination among the army and navy, and an unexpectedly vigorous rebel defense. His ego bruised, Clinton sought redemption in the North. As a man and as an officer, Clinton was very different from his colleagues. He had grown up in America, mostly on Manhattan, as the son of Admiral George Clinton, the governor of New York. After joining the army at age fifteen and training in France, Clinton served in Germany during the Seven Years’ War. Even though he had grown into an experienced officer, Clinton had never held an independent command. Unlike Howe and Burgoyne, he lacked self-confidence. The biographer of British wartime leaders Andrew O’Shaughnessy summarizes Clinton’s faults: “He sulked and brooded. He was jealous and tempestuous. He quarreled with colleagues.” But by the end of the American war, Clinton would be the longest-serving British commander in the entire conflict.52

Like his fellow commanders, Clinton preferred a peaceful settlement to war. Unlike the Howe brothers, though, Clinton had not opposed the British policies that had led to armed conflict. Upon arriving in Boston to assume his command in May 1775, he had advocated a harsh approach. At the same time, a memorandum of a conversation dated February 1776 suggests that Clinton approached the situation in the colonies with nuance: “I did not doubt but that this Country might be conquered, but did much [doubt] whether it was worth while to [have] it when conquered.” Clinton therefore concluded that “to gain the hearts & subdue the minds of America was in my opinion worth while.” But Clinton also had clear views on the military strategy most likely to lead to a British victory: in the absence of a political center of gravity—an established seat of American power—Britain must crush the Continental Army in order to force the colonials to seek a settlement. This contrasted sharply with Howe’s more cautious approach of using the minimum force necessary to demonstrate British superiority and thus compel the Americans to negotiate.53

This portrait of General Sir Henry Clinton adorned a wartime publication, the Reverend James Murray’s An impartial history of the war in America; from its first commencement, to the present time (Newcastle upon Tyne, 1782). Credit 22

The Seat of Action between the British and American Forces; or An Authentic Plan of the Western Part of Long Island, with the Engagement of the 27th August, 1776 (London, 1776). In anticipation of the British attack, Washington posted guards along the major roads through the Brooklyn Heights but left the Jamaica Pass exposed. Credit 23

Nevertheless, by mid-August, Clinton had managed to persuade Howe to adopt his proposal to envelop the American forces on Long Island. Having learned their lessons at Bunker Hill, the invaders now prepared for what they feared war against the insurgents entailed: officers removed the insignia from their uniforms lest enemy snipers identify them too easily. On August 22, as New York recovered from a severe thunderstorm that had killed three American soldiers in their tent, Howe landed 15,000 troops without opposition on Long Island. Misled by repeated intelligence failures, Washington had posted only 9,000 soldiers there, leaving the rest in Manhattan. Some 130 miles long and 20 miles across at its widest points, Long Island was sparsely populated with farming communities. Rich as it was in foodstuffs, and with a substantial neutral and Loyalist population ensuring good intelligence for the British, it was an excellent staging area for Howe’s invasion army.54

Over the next few days, Howe reinforced his contingent to a total of some 20,000 men. On August 27, Clinton’s plan delivered perhaps the greatest British triumph of the entire war. Clinton himself led the encirclement of Washington’s left wing, bringing some 10,000 troops virtually undetected through the undefended Jamaica Pass. Meanwhile, Hessian artillery and infantry with bayonets under General Leopold Philip von Heister attacked General John Sullivan’s forces south of Brooklyn Heights; when Sullivan realized that Clinton was about to trap him, he ordered a retreat to the heights. To the southwest, General Lord Stirling held off British forces under General James Grant until he, too, was about to be encircled and ordered a retreat; the British did capture Stirling. Many of the cornered American units experienced what Michael Graham, an eighteen-year-old volunteer with the Pennsylvania Flying Camp, described as a panicked rout, a scene of “confusion and horror,” with “artillery flying with the chains over the horses’ backs, our men running in almost every direction, and run which way they would, they were almost sure to meet the British or Hessians.” Although Graham survived, he was one of the luckier ones, escaping through swampy areas that claimed the lives of many a less fortunate comrade.55

The Americans pointed to the Hessians, in particular, as aggressive, immoral fighters. As they anticipated the Hessians’ arrival, it was suggested that Washington post 500 to 1,000 Patriots painted like Native Americans at German landing places in order to terrify the reputedly brutal enemy. Howe had in turn strategically used Americans’ fears of the ruthless Hessians by stationing them across from Washington’s camp at Amboy Ferry. According to later reports, during the action on August 27, Continental troops that could no longer resist sought to surrender to any forces other than Hessians, fearing that the latter were least likely to grant them quarter. One American soldier alleged that the Hessians “behaved with great Inhumanity” and “knocked on the Head of Men that were lying wounded on the Field of Battle.” There were even unconfirmed allegations of Hessians spitting enemy soldiers to trees with their bayonets and throwing hundreds of enemy corpses into a mass grave.56

One German officer, in a passage written in code in a letter home, admitted to atrocities against prisoners. When a regimental patrol brought some prisoners to camp, he detailed, “[m]any high ranking individuals at this time shed their ideas of being heroes. The prisoners who knelt and sought to surrender were beaten.” In addition, German soldiers did bayonet a number of Americans after they had given themselves up, although in at least a few cases this appears to have been in response to sham surrenders by Patriots who promptly resumed firing on the approaching Hessians.57

It may not have been the Hessians’ inherently aggressive disposition that led to all of these atrocities. A British officer in Fraser’s Highlanders summarized proudly that “[t]he Hessians and our brave Highlanders gave no quarter, and it was a fine sight to see with what alacrity they dispatched the Rebels with their bayonets after we had surrounded them so that they could not resist.” But then he revealed a psychological ploy to encourage the Germans’ ferocity: “We took care to tell the Hessians that the rebels had resolved to give no quarters—to them in particular—which made them fight desperately, and put all to death that fell into their hands.” Yet, he rationalized, “all stratagems are lawful in war, especially against such vile enemies to their King and country.” Hessian deserters later confirmed that Britons had sought to indoctrinate them; they had even told their German auxiliaries that the rebels cannibalized soldiers they took captive. British and German troops also accused each other of battlefield abuses, with one German officer reporting that the “English gave little quarter to the enemy and encouraged our men to do the same thing.” In fact, there is little definitive evidence that the Hessians fought more brutally in that battle, or violated the codes of war more egregiously, than did British units. By and large, atrocities appear to have been the exception rather than the rule. But when rumors, exaggerations, or even false reports resonated with Hessians’ sinister reputation, they could instill real fear and fan a desire for revenge.58

According to the best estimates, the Americans suffered between 300 and 500 casualties on Long Island; nearly 1,100 men were taken captive, including three generals. The redcoats, irate at American snipers, instantly destroyed the rifles of those they captured. British-German casualties totaled roughly 370, among them members of Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment. Displaying the characteristic optimism of British officers in the aftermath of the battle, Lord Percy wrote home that the Americans “will never again stand before us in the Field. Every Thing seems to be over with Them & I flatter myself now that this Campaign will put a total End to the War.”59

Long Islanders’ responses to their British invaders varied. One field officer felt “[t]he inhabitants received us with the greatest joy, seeing well the difference between anarchy and a mild regular government.” On the other hand, a Loyalist reported British atrocities against men and sexual abuse of women, without distinction between friend and foe. The would-be liberators also revealed themselves to be indiscriminate plunderers. In a letter to his father, the former British prime minister the Earl of Bute, Colonel Charles Stuart commented on the situation he had experienced on Long Island, where crews of British transport ships had started robbing the locals even as the battle was still raging. As Stuart saw it,

Those poor unhappy wretches who had remained in their habitation through necessity or loyalty were immediately judged by the soldiers to [be] Rebels, neither their cloathing or property spared, but in the most inhuman and barbarous manner torn from them…Thus we went on persuading to enmity those minds already undecided, and inducing our very Friends to fly to the opposite party for protection.60

Whatever the impact of the invasion on local civilians, Clinton’s plan was a tremendous strategic success: the American forces had been routed. But when Clinton urged Howe to press on and eliminate the Continental Army by landing the British troops north of Manhattan and preventing Washington from retreating across the King’s Bridge, Howe held back, apparently torn between his two roles as destroyer and peacemaker.61

The Americans seized their unexpected chance. During the night of August 29 and the morning of the thirtieth, undetected by the British, Washington evacuated some 9,500 men, with almost all their weapons and baggage, across the East River to Manhattan. A fierce nor’easter earlier in the evening had moved southwest by midnight; by morning, dense fog helped cover the retreat. Some of the Marblehead fishermen manning the rowing boats made five or even ten round trips with muffled oars. Washington was reportedly among the last to leave Brooklyn. His officers were astonished at Howe’s failure to pursue their badly beaten army after their rout on Long Island. General Putnam had only two possible explanations: “General Howe is either our friend or no general.” General Clinton, the mastermind of Britain’s earlier triumph, was clear also that “[c]omplete success would most likely have been the consequence of an immediate attack.”62

It is one of the great counterfactuals of the American Revolution that this was probably Britain’s best chance to end the war victoriously. Had Howe seized the momentum he had created on Long Island, pursued the Continental Army when their morale was low, trapped Washington in Manhattan, and delivered a decisive blow, it is quite likely that the insurgents would have had no option but to surrender and negotiate a settlement. Crushing the Continental Army, conjectures the historian Joseph Ellis, “would have generated traumatic shock waves that in turn would have destroyed the will of the American people to continue the war.” But instead of seeking the definitive strike that Clinton proposed, Howe pursued a more cautious strategy for the remainder of the campaign, informed in part by his concern to avoid large-scale casualties that would be hard to replace: between mid-September and mid-November, he gradually dislodged the Americans from their positions in New York, with partial victories at Kip’s Bay, at White Plains, and at Fort Washington, where he captured 2,600 American soldiers and more than 200 officers. By late fall, the British had driven the Continental Army from Long Island, Manhattan, and eastern New Jersey, the latter a crucial foraging area for the British Army that winter. In order to gain an ice-free harbor—New York’s more enclosed waters froze seasonally—they had also seized parts of Rhode Island. The British established their headquarters in New York City, where they would stay for the duration of the war.63

General Howe was later accused of allowing his pro-American sympathies to cloud his strategic thinking. But the Howe brothers’ real mistake was to assume that a British victory over the poorly prepared colonials was virtually inevitable even if maximum force was not applied. They also overestimated the strength of active Loyalism, relying on a counterinsurgency with overwhelming homegrown support that, in fact, never quite materialized.64

The Battle for American Loyalties

In July 1776, the final thread that had been tying the colonies formally to the Empire was cut. For the Patriots, there was now no turning back. As a newly sovereign state, the United Colonies—from September styled officially the United States—as well as the thirteen constituent states demanded undivided loyalty from those living in their territory. Across America, everyone, at least in principle, now had to decide whether to be a British subject and leave or remain as a citizen of America. Neutrality was no longer an option—not in theory, and not in practice, either: “Sir, we have passed the Rubicon,” John Jay told Beverley Robinson, a prominent landowner in the Hudson Valley who was still bent on neutrality, early the following year, “and it is now necessary every man Take his part.” For the Revolutionaries, allegiance was volitional: all individuals were given a period of grace to pledge their loyalty to the British Crown or to the United States. Given a generous six weeks to make up his mind and sign an oath, Robinson eventually evacuated his family behind British lines.65

After they had declared their independence, the Patriots put their policing of political loyalties on a stronger legal footing. First, the Congress and then the states passed treason laws and confiscation and banishment acts. Preparing in June 1776 for the eventuality of independence, Congress had already defined treason as levying war against the United Colonies, adhering to the king of Great Britain, or giving the enemy aid or comfort. Recruiting for the enemy and joining them—even acting as a local guide—became capital offenses. John Adams, who denounced the Loyalists as “an ignorant, cowardly pack of scoundrels,” was buoyant, judging that the treason laws would “make whigs by the thousands…A treason law is in politics like the article for shooting upon the spot a soldier who shall turn his back. It turns a man’s cowardice and timidity into heroism, because it places greater danger behind his back than before his face.” Eight states banished named Loyalists and threatened to execute them in the event that they ever returned. Over the course of the war, several states would execute convicted Loyalist traitors.66

In addition to treason laws, the states enacted test laws, which required citizens to swear loyalty towards their states of residence. In most areas, the relative harshness of anti-Loyalist laws depended on how strong pro-British sentiment was perceived to be and which side had the upper hand militarily. In New Hampshire, where active Loyalism was fairly marginal and where the war had a limited direct impact, oaths of allegiance were only required from state servants, officers, and lawyers, starting in late 1777. By contrast, residents of the strongly Loyalist Westchester County in New York were at much greater risk of being declared open enemies. Under the direction of New York’s Committee for Inquiring into Detecting and Defeating all Conspiracies, and supported by a sizable militia, local committees would go on to try some 1,000 individuals by 1779. During that same period, Loyalist refugees swelled British-controlled New York City’s population to 33,000.67

The repercussions for those who did not comply with the test laws were typically harsher than the punishments for those who had refused previous loyalty oaths. They were now regularly banned from voting and barred from holding office, practicing their professions, and trading. Nowhere could they serve on juries, acquire property, inherit land, or even travel at will. Confiscation of property affected tens of thousands of Loyalists during the war, allowing the states to accrue assets and condemn traitors to a social death without engaging in widespread executions. Some refugee populations were repeatedly dispossessed and displaced, like the Connecticut Loyalist exiles who retreated to Long Island, only to be targeted there by Patriot raiding parties across the sound.68

In this messy period of transition, as prosecutions under the new laws intensified, committees and mobs across the colonies continued to spread terror among Loyalists and waverers alike. In today’s Darien, Connecticut, an “American guard” arrested Walter Bates, the fifteen- or sixteen-year-old son of an Anglican Loyalist family. The Patriots suspected Walter of knowing the whereabouts of fugitive armed Loyalists, including his own brother, who were thought to be hiding out in the neighborhood. His interrogators, Walter later recounted, “threatened [him] with sundry deaths,” including by drowning, unless he confessed. At night, an armed mob took Walter to a local salt marsh, stripped him naked, and tied him by his feet and hands to a tree. He despaired that over as little as a two-hour period, the mosquitoes would draw “every drop of blood…from my body.”69

After they had softened him up, two of the committee members then presented Walter with a choice: either he could confess and be released, or he would be handed back to the mob, which might well kill him. When he refused, Walter was told he would receive a punishment of one hundred lashes. If the whipping did not kill him outright, Walter was reassured, he would be hanged. After an initial twenty lashes had been administered, Walter was returned to the guardhouse, to be further “insulted and abused by all.” His tormentors had apparently reconsidered the lash count, but Walter’s ordeal was far from over.

The following day the committee discussed various means of extracting a confession by torture. As Walter told it, “[T]he most terrifying was that of confining me to a log on the carriage in the Saw mill and let the saw cut me in two.” After the agonies he had already been through, Walter had every reason to assume the Patriots meant business. But then his fate turned again. Reprieved from meeting his end as a human log, Walter was brought before a man he referred to as Judge Davenport. Marveling that he had never seen anyone withstand greater suffering without exposing his comrades, Davenport eventually ordered Walter released. Like many persecuted Loyalists, he lay low in the woods and mountains until the “frenzy might be somewhat abated.” His sacrifice was not in vain: Walter’s brother managed to evade the Patriot search parties and went on to fight with General Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown.

As the Tory hunting intensified across the states, women and entire families increasingly felt the impact, too. In most states, confiscation laws mandated that family members abandoned by male Loyalist refugees be left with some clothing, furniture, and provisions when their estates were seized. In Massachusetts, a wife’s customary right to a third of her husband’s property remained protected. In South Carolina, by contrast, even wives who did not share their husband’s Loyalist sentiments were considered guilty by association unless proven otherwise. Being displaced from their homes and seeing their belongings taken from them carried a tremendous psychological cost for the women and families affected. Rachel Noble, the widow of an active Loyalist in New Jersey, recorded the harassment she suffered at the hands of her neighbors in Ramapo. Narrowly escaping arrest by local authorities, she fled “with an infant at her Breast on foot and unprotected and suffered everything which can be felt from Terror, Inclemency of Weather [and] want of Food.” Noble left three more children at the mercy of the Patriots, who stripped them of their clothes and pillaged and destroyed their home. After an odyssey of escape and imprisonment, Rachel was eventually reunited with her children in New York; in 1780, all departed for England.70

Women who actively assisted the British by aiding prisoners, ferrying goods across the lines, or gathering intelligence knew they were risking particularly severe treatment if found out. The New Yorker Lorenda Holmes “was stripped by an angry band of committeemen and dragged ‘to the Drawing Room Window…exposing her to many Thousands of People Naked.’ ” On that occasion, Holmes, who apparently had been smuggling letters in her underwear from a British warship to Long Island, escaped with “shame and horror of the Mind.” Not only did Holmes continue to carry secret mail, but she also guided Loyalist refugees to safety in a British camp. When the latter activities were discovered, an American soldier came to her house to execute a more physically painful form of punishment. Making Holmes remove her shoe, her tormentor took “a shovel of Wood Coals from the fire and by mere force held [my] right foot upon the Coals until he had burnt it in a most shocking manner.” As he did so, her assailant admonished her that “he would learn [i.e., teach] her to carry off Loyalists to the British Army.” Patriots may have felt that she got off lightly for treason, but Holmes no doubt had the consequences of her loyalty seared into her mind as much as into the sole of her foot.71

Like Lorenda Holmes, other American Loyalists, too, experienced Revolutionary terror at the hands of Continental soldiers, not just their civilian neighbors. In May 1777, a North Carolina unit under General Francis Nash moving through Richmond, Virginia, was followed by a shoemaker shouting, “Hurray for King George!” When he had had enough, Nash ordered his men to take the shoemaker to the James River: “The soldiers tied a rope around his middle, and seesawed him backwards and forwards until we had him nearly drowned, but every time he got his head above water he would cry for King George.” The general next ordered a tarring and feathering, but the shoemaker “still would hurrah for King George.” Drummed out of town, and told not to return at the threat of being shot, the shoemaker never yielded to his tormentors.72

Over the months and years following independence, Patriots would continue the purgation of American communities by prosecuting, physically harming, and imprisoning their Loyalist neighbors. Thirty thousand Loyalists ultimately fled their homes for the British garrison cities of New York, Charleston, and Savannah—a share of the colonial population that corresponds to some 3.8 million Americans today. By 1781, New York had recovered its prewar population of some 25,000 citizens, not including the fluctuating numbers of armed services personnel. Ten thousand Loyalists left America altogether during the war; 19,000 enlisted in Loyalist corps to fight alongside the British Army; thousands more volunteered as partisan fighters. Off the battlefield, too, Loyalists died for their political beliefs and actions, killed by mobs or at the hands of marauding bands, hanged by order of councils of safety or assemblies in various states, or executed following court-martial. But in a civil war, violence flows both ways, and for the next six years Loyalist soldiers as well as prison guards would commit both legitimate and illegitimate violence. “We are cast into a strange friendless world,” bemoaned a correspondent of Continental Congress president John Hancock, “where Nation against Nation, Family against Family, and Man against Man are embattled and opposed to each other, tearing every Enjoyment, every Property, and even Life itself from the Possessor.”73

Even while the leaders of the new United States were clamping down on internal dissent, General Sir William Howe was already launching his own loyalty offensive. At the end of November, as his army was advancing steadily to clear the Continentals from New York, Howe issued his fourth proclamation that year. It offered a pardon to all rebels who would submit within sixty days. When Howe tested the allegiance of Suffolk County by asking for two hundred wagons to move his army’s baggage, the local population helped him exceed his target. To London, the Howe brothers reported that reassuring numbers of rebels were coming into British lines. Already, there were some 1,900 on Long Island and 3,000 in New Jersey in the first week alone, some 15 percent of all free male adults. But Secretary Germain warned that granting insurgents amnesty risked alienating the long-suffering Loyalists. He instructed Howe to proclaim publicly that all those rebels who failed to submit within sixty days, and anyone not meriting a royal pardon, were to receive their due punishment. As the British leadership remained divided on the strategies of violence and restraint, Germain needed to see the stick being waved alongside the dangling carrot. There must be no doubt that death always remained a possibility for a rebel.74

The American Patriots had scored some early rhetorical victories with their opening salvos over Lexington and Concord and in the aftermath of the British bombardments of port cities, enhanced by the cover-up at Norfolk. They had centered their declaration of independence on George III’s illegitimate violence that helped legitimate their break from the mother country. After Howe had failed to trap Washington in New York, the war looked set to move into another campaign season. If the American Revolutionaries wanted to seize and retain the moral high ground, they would need to continue to discredit the British as barbarous. At the same time, they must set a positive example, a virtuous counterpoint to their enemy’s alleged viciousness. It was a mission that Washington stood ready to embrace. But it remained to be seen how well his moral leadership would hold up under the pressures of command, and amid the contingencies and hardships of war.

Thomas Pownall and Samuel Holland, The Provinces of New York and New Jersey; with part of Pensilvania, and the Province of Quebec (London, 1776). Credit 24