It must have been one of the most emotional and nerve-racking journeys of Ward Chipman’s young life. Not that it was his first dangerous trip. Seven years earlier, in spring 1776, the then twenty-two-year-old Harvard-educated lawyer, known to his family and friends as “Chip,” had fled from the countryside to Boston and then evacuated that town with the British. Given his position as a clerk-solicitor in the Custom House and a signatory to a loyal address to General Gage—along with his public association with prominent Loyalists like his mentor, Massachusetts attorney general Jonathan Sewell—Chipman’s decision had surprised no one. He left after transferring what limited property he possessed to his mother and five siblings lest the rebels confiscate it.1

After a frustrating year in exile in London, Chipman had returned to New York City to serve the occupying British Army as deputy muster master general. Soon he was also practicing as a private lawyer. By 1782, his annual income amounted to a sizable £500. But when news broke, in spring 1783, that the United States had concluded a preliminary peace treaty with Great Britain in Paris the previous November, his future—and that of hundreds of thousands of Loyalists in America—seemed precarious.

British and American envoys in Paris had been in peace talks since April 1782, and the treatment of Loyalists was the first issue they considered. It was also the last item they resolved. Even after American independence had been conceded, fishery rights agreed upon, and territorial disputes and boundary questions settled—the United States was granted a land area totaling 900,000 square miles, compared to the thirteen colonies’ 384,000—the status of the Loyalists remained a sticking point. So did the question of compensation for property and income they had lost due to persecution and war. Among America’s negotiators, Benjamin Franklin was the most passionate opponent of generous measures for the Loyalists. Franklin—who never forgave his own son, William, for his Loyalism—demanded that any compensation be tied to reparation payments to the United States for wartime damage caused by British-Loyalist forces, citing the burning of towns such as Falmouth and Norfolk, and the butchering of men, women, and children by British-allied Indians. Franklin’s co-negotiator, the New York lawyer John Jay, had sustained ties with Loyalist family and friends during the war. Yet Jay now also warned that Americans would rather fight for another half century than “subscribe to such evidence of their own iniquity” as allowing “provision for such cutthroats.”2

In the end, the preliminary articles of peace, signed in Paris on November 30, 1782, called for Congress to “earnestly recommend” that the states restore confiscated estates and properties belonging to “real British subjects”—referring to individuals to whose loyalty American states made no claim, such as former governors Dunmore and Tryon—and those residing in districts then held by the British who had not borne arms against the United States. Other wartime exiles would be allowed to return for twelve months to try to recover property. While states were free to comply with these recommendations at their own discretion, the treaty required them to grant a general amnesty, forbade further persecutions and confiscations of property, and demanded that ongoing prosecution cases be closed. Americans, the treaty decreed, should move peacefully beyond their wartime divisions.3

In London, Lord North, the former prime minister, and his circle stridently condemned the government’s handling of the Loyalist question. Richard Wilbraham Bootle, an independent Member of Parliament, also considered the treatment of Loyalists “scandalous” and “disgraceful”: these were “men, so cruelly abandoned to the malice of their enemies….They had fought for us, and ran every hazard to assist our cause, and when it most behoved us to afford them protection, we deserted them.” In April 1783, the treaty, and related accords with France and Spain, helped topple the government of the new prime minister, the Earl of Shelburne, the former war critic who had headed the administration since July 1782. Concessions of land, from Florida and Tobago to Senegal and territories in India, were in part to blame, but the perceived betrayal of the American Loyalists—not least the nonbinding treaty provisions—clearly played a role.4

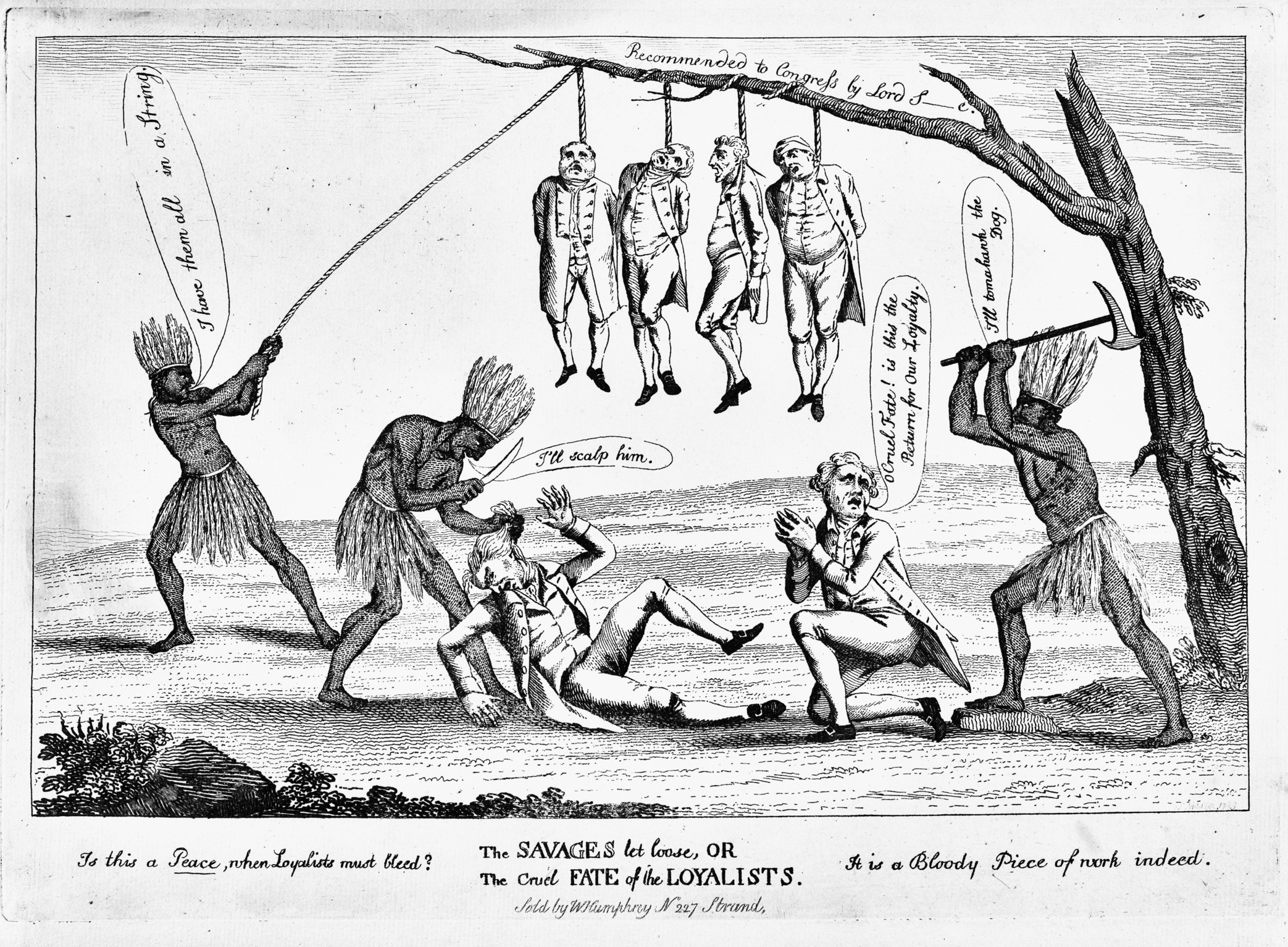

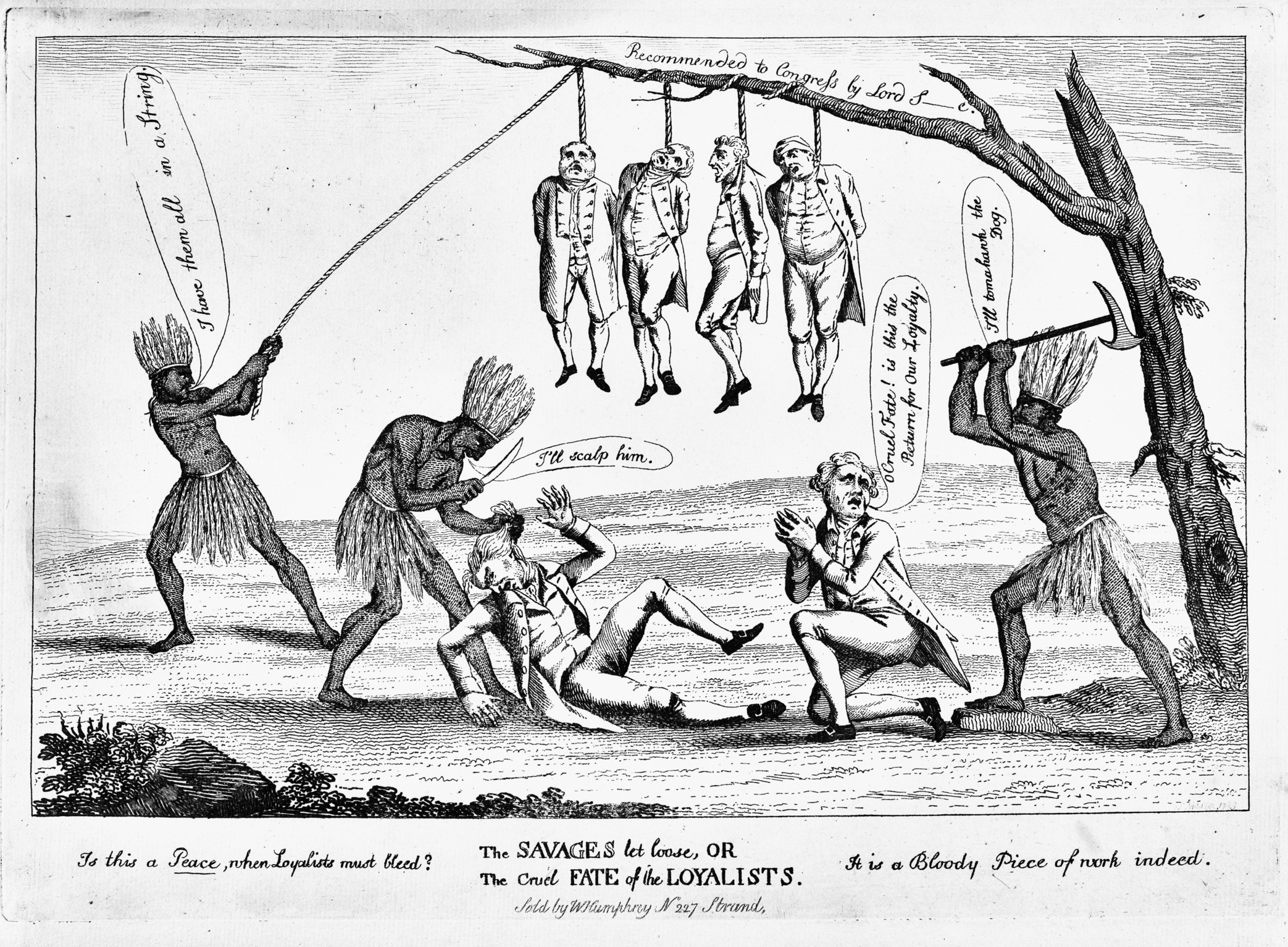

Graphic satirists had a field day when the government apparently disowned Britain’s loyal American subjects. Engravings depicted British visions of Indians—literally and figuratively; that is, American Patriots imagined as Indians—slaughtering, tomahawking, scalping, and hanging Loyalists.

In one print, entitled Shelb—ns sacrifice, Britannia is attacking a smiling Shelburne with a spear; an English butcher is weeping at the sight of Native Americans assaulting well-heeled Loyalists. In another, The Savages Let Loose, Indians are hanging and threatening to tomahawk and scalp Loyalists.

Shelb—ns sacrifice / invented by Cruelty; engraved by Dishonor: Or the recommended Loyalists, a faithful representation of a Tragedy shortly to be performed on the Continent of America (London, Feb. 1783). Credit 53

The Savages Let Loose, or The Cruel Fate of the Loyalists (London, Mar. 1783). Credit 54

When they learned of the preliminary treaty, Loyalists felt they had been betrayed. But as Abigail Adams, writing to her husband, John, the third U.S. negotiator in Paris, rightly predicted, even America’s relatively weak concessions “raised the old spirit against the Tories to such a height that it would be at the risk of their lives should they venture here.” The potential return of thousands of Loyalists from temporary exile—seeking restoration of property and even running for public office—incited deep anxiety among their Patriot neighbors. Zabdiel Adams, John’s cousin, felt the British had at least “virtually acknowledged their faults” and it was therefore “our duty to forgive, if not forget.” The Loyalists, by contrast, could not be forgiven, much less integrated in the new nation. A decade of brutal civil war had habituated Americans to violent conflict resolution and generated a thirst for vengeance that no treaty could quickly assuage.5

If the 60,000 or so white Loyalists who went into permanent exile after the war faced uncertain futures, the several hundred thousand who wished to stay in their home communities or return there had to brace themselves for what might lie in store. They knew that animosity towards Loyalists ran deep and that their former neighbors would be unlikely to receive them with open arms. Soon the returnees—and those who had remained in their communities during the war—found out that they would need to deal with legal discrimination, renewed persecution by crowds and committees, and possibly violent expulsion. Even so, a mixture of economic pragmatism, the strength of family and neighborly ties, and genuine tolerance ultimately led many communities to reintegrate, if not embrace, their Loyalist members.

Ward Chipman initially seemed unperturbed by news of the peace treaty. He planned to hunker down in New York and continue practicing the law. But soon the victorious Patriots banned Loyalists from the New York bar. Chipman, like tens of thousands of Loyalists, now weighed his options: Should he stay in America, either in New York or his native Massachusetts, or should he start a new life in exile, perhaps in Britain, or its remaining colonies? Chipman’s friend Thomas Aston Coffin, a fellow Harvard graduate and Loyalist, had spent much of his war aiding the British in New York and Philadelphia, most recently as a secretary to Carleton. Two of Tom’s brothers fought with the British Army. His father lived out the war on Long Island, while his mother and sisters stayed behind in Massachusetts, trying to protect the family property from confiscation. The Coffins had been keeping in touch by correspondence, but Tom had not seen his mother and sisters since 1776. By year’s end, Coffin, like Chipman, had to decide where to go when the British evacuated New York.6

That spring, the last forty or so American prisoners were released from the prison ship Jersey in New York City, along with the final two prisoners from the Provost (both civilians held on charges of treason). Among the Jersey survivors was William Russell, a Boston schoolteacher who had been present at the Tea Party, saw his home plundered by Anglo-Loyalist forces, served thirty months in the Patriot militia, and was eventually captured on a privateering ship. After nearly three years at the Mill Prison in England, Russell had been among more than 1,000 American captives the British released during the 1782 peace negotiations. But as the war was not formally over yet when William arrived in Boston in August 1782, he joined another privateer—only to be captured again and imprisoned on the dreaded Jersey, the “awfulest place I ever saw.” Weakened by the tuberculosis he had contracted on the Jersey, Russell would die in Cambridge at age thirty-five, less than a year after his final release.7

While former Patriot captives were returning to their families—some, like William Russell, only to become delayed casualties of war—the signs were also pointing towards further violence between America’s Patriots and Loyalists. In April 1783, as Americans learned that their envoys in Paris had signed an armistice, town meetings in Boston resolved to give returning Loyalists a warning of just six hours to leave voluntarily before being deported. Communities across the state followed Boston’s lead, putting on notice those “declared Traitors to their Country.” Marblehead, Massachusetts, Chipman’s hometown, resolved to prevent the return of Loyalists lest their readmission spark renewed civil war and conflict with Britain. The Roxbury committee opposed the return of “Absentees, Conspirators, Refugees, and Tories” who threatened to become a Trojan Horse for the “Crafty Machinations of Britons.” Some Patriots were even using the language of extirpation that had previously been reserved for Native Americans: the Loyalists were “villains, scoundrels, double hearted knaves” who should be “Extirpated from the Face of the Earth.”8

As Chip must have known, when belligerent committees issued threats, and when Boston newspapers warned Loyalists of the gallows awaiting them on Copp’s Hill, they weren’t just scaremongering. Accounts of verbal and physical abuse of Loyalists were circulating widely, both by word of mouth and through the press. A Mr. Triest returning to Townshend, Massachusetts, was promptly picked up and fitted “with a handspike [a wooden rod with an iron tip] under his crotch, and a halter around his neck.” His assailants strung Triest up on the masthead of a sloop overnight. When they took him down after sixteen hours, they put him in irons and deported him and his family by boat. Under duress, Triest signed a paper promising not to come back, on pain of death. Throughout that spring and early summer, Loyalists returning to the state to recover debts or property as the peace treaty permitted were arrested and subsequently imprisoned or deported. As Patriots revived their committees of inspection and observation to prepare for the Loyalist influx, they exercised long-standing grudges. They also distinguished between degrees of Loyalist culpability. Particularly severe violence awaited anyone who had actively aided the British.9

This was especially the case for former Loyalist soldiers like Cavalier Jouet. That spring, Jouet came home to New Jersey to explore the possibility of recovering confiscated property and resettling his family there. He chose to enter via the Woodbridge area, where he had been a prisoner on parole for three years during the war and where the locals had treated him with civility. But now, Jouet reported, “I received the most outrageous insults and narrowly escaped the most shameful and degrading abuse.” Some of the same men who had previously been courteous now wielded sticks and whips. Once peace had rendered void all paroles, Jouet had no right to be in their town, and they were “determined to give (as they insultingly called it) a Continental Jacket” to this American traitor. The local citizens, with the support of their magistrates, had formed an association to expel by whipping any would-be returnee. A justice, no less, escalated matters further, shouting: “Hang him up, hang him up!”10

With the help of a local clergyman and a man who claimed that Jouet’s son had once helped him when he was a captive himself, Jouet eventually escaped and reached the safety of British lines. Personal motives, of gratitude or honor, could determine the fate of returning Loyalists such as Jouet as much as abstract political principles and community sentiment. Others connected to the British Army were less fortunate when they returned to the Woodbridge area, and this perhaps gave rise to the dictum of Peter Oliver, formerly the chief justice of Massachusetts’s highest court, that in New Jersey “they naturalize [returnees] by tarring and feathering.”11

To the north, Prosper Brown, who had served on a British privateer, went home when the war was over to claim property in his native New London, Connecticut. Brown was promptly seized by a “licentious and bloodthirsty mob and hung up by the neck with his hands tied onboard a vessel laying alongside the wharf.” They subsequently took him down, stripped him, flogged him with a cat-o’-nine-tails, and tarred and feathered him before again hanging him up the yardarm, this time naked, “exposed to the shame and huzzas of the most diabolic crew that ever existed on earth.” Finally released, though not without first being robbed of the money he carried, Brown was shipped back to New York with the injunction never to return on pain of death. He begged Carleton to evacuate his family of four to Nova Scotia.12

All around Chipman and Coffin, thousands of Loyalists—soldiers and families, white and black—were now preparing to depart New York City on Carleton’s amassing fleet. But many others still held out hope that they might be able to stay or return to their home communities, despite the escalation of anti-Loyalist sentiment. In their precarious situation, some Loyalists preemptively collated evidence in self-defense, such as the three widows who had former Patriot prisoners testify in writing to their relief efforts during the war. A Dr. Richard Bayley claimed to have cared well for wounded prisoners and published statements of survivors and Patriot officials to that effect, although others accused the doctor of cruelty. Bayley and his young daughter Elizabeth, later to be canonized as the first American-born saint, did manage to stay in America.13

In May, Carleton, who was “much affected by the dishonorable Terms” regarding the Loyalists, alerted the British government to the renewed terror they were facing: “Almost all of those who have attempted to return to their homes have been exceedingly ill treated, many beaten, robbed of their money and clothing, and sent back.” Such stories, and the fear, confusion, and distress they reflected, would probably have come to the attention of Chipman, and even more likely of Coffin, who served on Carleton’s staff. As they considered their own options, the two friends surely sensed the real danger to Loyalists across America. That month, Chipman informed a London contact that he would go into exile “unless there is a great change in the temper and conduct of the Americans who are at present very violent and threaten proscription & exile to every man who has adhered to the King’s cause.” Carleton meanwhile was delaying the evacuation of New York: he agreed with Lord North that the king’s sense of duty and Britain’s honor demanded that every American Loyalist who wished to elude the “violent…associations” and the “barbarous menaces” of committees be found a space on his ships.14

While the diplomats continued to negotiate a final treaty in Paris, Patriots in America ramped up their anti-Loyalist agitation—and not just in the areas of New York and New Jersey and the South where regional civil wars had wreaked the most havoc but throughout the country. Patriots held public gatherings in ten states. Legislatures and executives enacted discriminatory policies from New England to the lower South. With Revolutionary committees back in operation, militias scouring the countryside, and courts ready to issue indictments, the Revolution’s victors were prepared to once again use their apparatus of oppression and terror against their domestic enemies.15

By September 1783, Ward Chipman seemed to have given up any hope of staying in what felt like a country yet again succumbing to mob rule. He decided to settle permanently in Nova Scotia. First, though, he wanted to undertake a farewell journey to see his family, from whom he had been separated for nearly a decade. Thomas Coffin would accompany him. The diary Chipman kept of their travels—from New York via Connecticut to Boston and his native Marblehead, Massachusetts, then back via Rhode Island—makes palpable his anxiety. Given how strained the atmosphere in the war-torn country had become, neither he nor his Loyalist companion could predict how vengeful Patriots might receive them.

Final Journeys

On September 21, Chipman and Coffin left New York in an open carriage, their pistols loaded. Within a day, they were crossing Westchester County, where bands of robbers controlled a landscape altogether “barren, poor, and desolate, not a house with a whole window, many without any at all.” Earlier that year, in this very area, the elderly Loyalist grandee Oliver DeLancey had been beaten “in a most violent manner.” Now a gang under Israel Honeywell had once again gone Tory hunting. Isaac Foshay, formerly of Philipsburg, had left his farm in the care of his son William, who sided with the Patriots; Isaac fled to the British lines. After peace terms had been agreed upon, Isaac had returned to his farm; but Israel Honeywell, ostensibly in his capacity as “commissioner,” approached the area with thirty to forty armed men, intent on seizing the elder Foshay “dead or alive.” He ordered William to drive his father, who was too ill to walk or ride, to Morrisania, “shaking his sword over s.:d W.:ms head to make him drive faster telling him to drive his Corpse to Nova-Scotia.” Isaac, whom William dragged along on a wooden sled, started spitting blood and died within days. Such cruel expulsions, which made the Patriot son complicit in his Loyalist father’s final ordeal, laid bare the deep rifts in the community after years of civil war.16

Had they turned to the northwest, Chip and Coffin would have encountered pillars on the roads leading into Albany County carrying this sinister inscription:

Ye Enemies to American Independence, take

heed to the following:

Turks, Pagans, Jews, ’tis a true story,

May enter here before a tory;

The many crimes by them committed,

Prevents their being here admitted.17

Instead, they proceeded into Connecticut, where a chance encounter with General Benjamin Lincoln, the American secretary of war, at Horseneck (West Greenwich), provided the travelers with a brief respite from their worry. Over a shared bottle of Madeira, Lincoln showed himself “very affable & polite” as he chatted with Coffin about old Boston friends. Earlier in the year, Lincoln had expressed concern about the intimidating editorials in the Boston press, which he feared would drive Loyalists into exile to the demographic and economic detriment of the U.S.—arguments that foreshadowed those made by conciliatory Patriots later on. Chipman and Coffin passed through Stamford, still badly damaged from British raids, where several returning Loyalists alleged to have fought for the king had recently been assailed by an armed party and beaten with split hoop poles. Yet it was also in that area that they witnessed the joyful reunion of the Lloyd brothers: the Patriot merchant John; Henry the Loyalist, who had fled in 1776; and the Loyalist doctor, James, who had spent the war in Boston.

At Springfield Ferry, where the American Supreme Court was then sitting, Chipman “felt for the first time an uneasiness lest we should be known. There was a great concourse of people & had they found us out, we should probably have been insulted. Tom tho’t one man walk’d round him in a suspicious manner. I conceited I saw Violence and resentment the characteristic of them all.” Apprehensive they might get into trouble, the friends decided to leave early, though “coolly to all appearance.”

As they approached Boston, Chip became increasingly nervous. Even harmless occurrences rattled him. When they eventually arrived, Chipman learned that the rebels had confiscated his mentor Sewall’s house. Feelings were welling up inside him of “[p]ity, resentment, indignation, grief…But as I pass’d the house, I felt the influence of other sensations, the effect of which will not suddenly be lost.” He was now truly afraid, for in the fall of 1774 he had helped defend the Sewall residence against a violent Revolutionary mob. Cautiously, Coffin and Chipman slipped through the back door into an old acquaintance’s tavern “& skulked into the little back Room, with all the circumspection & conscious Guilt of the vilest miscreants.” After dusk, they ventured out on a clandestine tour of old college haunts, ending the night in “hush’d conversation” with a friend over a bottle of wine. Daylight brought reassuringly civil encounters about town. When Chipman finally saw his sister, Nancy, it was a moment “worth a world,” followed by an affectionate reunion with his mother in Marblehead.

Friends urged Chip to return permanently to Massachusetts and rebuild his life there. Throughout the thirteen states, many Loyalists did indeed reactivate prewar friendships and draw on family connections to facilitate their return. While revolution and war had split many families, elsewhere the ties of kinship and friendship had held fast, even in the environs of the main British garrison city, New York. After 1783, these networks enabled Loyalists to recover confiscated property, collect evidence in hope of future compensation, and obtain pardons as well as residency and citizenship rights. But while some Loyalists rejoined their families and recovered property, albeit often with substantial taxes affixed, others were discouraged by what they learned. Many were actively prevented from returning even for brief visits, the guarantees in the peace treaty notwithstanding. (As late as August 1784, a Boston mob would tar and feather one returnee.) Despite his friends’ pleas, Ward Chipman’s mind was made up; he and Coffin departed with heavy hearts for New York City, to go from there into exile abroad.

Chipman and Coffin had never taken up arms for the British. Their former communities harbored no specific grievances against them. They weren’t even planning a permanent return. And yet, even these two comparatively inoffensive men feared for their safety on a brief visit home, indicating just how volatile and dangerous the immediate postwar period must have felt for Loyalists across America. As Chipman and Coffin prepared for exile, reports of the terror of physical and mental abuse that Patriots were once again unleashing against Loyalists kept coming in from across the states. Threats of physical violence against returnees persisted right up to, and indeed beyond, the departure of the last evacuees: “a bitter and neck-breaking hurricane,” wrote one New York paper, would visit any Loyalists who failed to go into exile. Coffin and Chipman held out until the final evacuation in November 1783. Chip first sailed via Halifax to England; he later settled in Nova Scotia to practice law and help create New Brunswick. On November 25, 1783, Coffin sailed at General Carleton’s side out of the New York harbor en route to England.18

In January 1784, Congress ratified the final peace treaty, which had changed little from the preliminary version; the implementation of key provisions concerning the Loyalists would be left to the states’ discretion. Ignoring the congressional recommendation that they comply fully with the treaty, many states still refused to modify their anti-Loyalist programs. A total of nine states either enforced existing confiscation laws or passed new ones in contravention of the peace accord. New Jersey, Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina had each enacted discriminatory citizenship laws before January 1784 and now failed to rescind them. Massachusetts enacted a new banishment law in March: all aliens—defined as those who had joined the British military or had left between October 1774 (when Congress had passed the Continental Association) and 1780—would be expelled, their estates forfeited to the state, yet another violation of the peace treaty. An amnesty clause introduced in June triggered popular protests and warnings of the feuding horrors that might ensue. In Virginia, as late as 1786, legislation prohibited Loyalists from voting or holding public office.19

In the South especially, the wounds of war still felt very raw. South Carolina had at first ordered returning Loyalists to leave immediately. Members of the Marine Anti-Britannic Society, formed by the commander of the state’s navy, Commodore Alexander Gillon, agitated against returnees and picked street fights. A poet who was attacked pointed to the enduring split in local (and national) society: “Who can brook a Rebel’s frown?—or bear his children’s stare / When in the streets they point, and lisp, ‘A Tory?’ ” Auctions of confiscated Loyalist property continued in the interior. Even as the South Carolina state legislature gradually removed restrictions on individual Loyalists, citizens continued to intimidate their traitorous neighbors—hanging them in effigy, threatening their families, ordering them to leave the state. Elsewhere, Patriots staged frequent nighttime raids on private homes, menacing residents with swords while ransacking their property.20

For some men, the journey home proved fatal. During the war, Matthew Love had participated in Loyalist raids in the Ninety-Six district of South Carolina. When he returned to the area in 1784, locals recognized him and charged him with murdering wounded Patriot combatants and prisoners during the war. Gruesome details surfaced of how Love had walked around after a skirmish in 1781 stabbing wounded and dead opponents with his sword, among them his former neighbors. But the judge presiding over his trial, Aedanus Burke, had annulled the charges, arguing that under the peace treaty Love enjoyed immunity from prosecution. Love was released. The local citizenry, however, was less forgiving: they hanged him from a tree.21

Whether a place was more or less conciliatory towards Loyalists, and whether an individual Loyalist received a hostile or friendly welcome, depended on a whole host of factors. Political leaders at state and local levels set the tone either for exclusion or integration. Areas with smaller proportions of wartime Loyalists who had maintained social and economic ties with Patriot neighbors and family, and who were perceived to pose a relatively low threat, were reintegrated more easily than communities where divisions had run deeper, especially if they had also experienced British occupation, high levels of military violence, or both. As we have seen in the case of Matthew Love, communities took into account the wartime record of individual returnees. Memories of vocal, and especially of violent, Loyalism, as well as personal grudges, inspired the strongest desire for revenge.

Some towns took a pragmatic approach to furthering their postwar economic recovery by embracing Loyalists who offered skills and services that were in local demand. But then, economic self-interest could also work against harmonious integration, especially if locals saw a particular would-be returnee as a potential rival in trade or wanted to keep a prewar creditor at bay. With so many factors in play, and states failing to comply fully with the peace treaty’s push for reconciliation, Loyalists across the United States experienced the immediate postwar period as a time of renewed uncertainty and unpredictability.

Reconciliation

Judge Burke, who tried to save Love, was an outspoken advocate of reconciliation. Publishing under a pseudonym, Burke argued that anti-Loyalist measures must be revoked and discriminatory legislation struck from the record. An act of general amnesty ought to be passed, just as after the English Civil War of the previous century. Even though the British had been guilty of cruel and violent oppression in America, and even though South Carolina alone had suffered the deaths of 3,000 white men, the loss of 20,000 slaves, and considerable damage to property, he argued, Americans must move beyond their wartime differences. If the survivors of the much more violent English Civil War had been capable of healing rifts, then surely it was time now for Americans of all political persuasions to “shake hands as brethren, whose fate it is to live together.” Reconciliation would “stand as a more lasting monument of our national wisdom, justice and magnanimity, than statues of brass or marble.”22

Judge Burke was not alone. Concerned about preserving the Revolution’s ideals and maintaining America’s international reputation as an honorable, treaty-abiding nation, an increasingly vocal group of individuals, General Washington prominently among them, began pushing for reconciliation. After winning the moral war, they believed, America also had to win the peace by conducting itself in accordance with international law and enlightened ethical standards—even, or especially, when it came to the Loyalists. If dead Patriot heroes could comment, said Israel Evans, formerly a chaplain in Sullivan’s army in Iroquoia, “they would ardently pray you to forgive your and their enemies, rather than to indulge any ignoble passion of resentment and revenge, which any ways be injurious to the credit and reputation of the confederated States.” One of the key figures of the postwar era, Washington’s former close aide Alexander Hamilton, took a strong stance on reintegrating the Loyalists. Hamilton—who had also argued against retaliation in the Huddy-Asgill affair—had returned to New York towards the end of the war, studied law in Albany, and quickly gained admission to the bar. Short and slight, elegant and charming, the twenty-nine-year-old Hamilton was a rising lawyer in a city seeking to negotiate the transition from war to peace.23

A decade earlier, on the eve of the war, Hamilton, then a precocious student at King’s College (today’s Columbia University), had witnessed an incensed crowd march on the house of the college president, whom they suspected of leading a Loyalist network. They apparently intended to tar and feather him. Hamilton held off the mob so their target could escape over a fence. With popular violence continuing to grow, Hamilton cautioned that in politically turbulent times, when “the passions of men are worked up to an uncommon pitch there is great danger of fatal extremes.”24

As Loyalists in New York and elsewhere were once again being tarred and feathered, Hamilton took up his pen. Writing under the apt pseudonym “Phocion”—the Athenian soldier who served a great general and later advocated conciliation with former foes—Hamilton warned of the diplomatic, political, economic, and moral costs of persecuting the Loyalists. In the face of violence and legal discrimination, he urged tolerance. Hamilton insisted that the rights of Loyalists be safeguarded: this was the best way to preserve liberty and stability in the new nation. Embittered Americans, he observed, allowed their thirst for “revenge, cruelty, persecution, and perfidy” to drive arbitrary expulsions and disfranchisement without trial by jury. Instead, law, order, and justice must prevail over “the little vindictive selfish mean passions of a few.” In addition, as the “world has its eye upon America,” the new republic needed to “justify the revolution by its fruits”—even, and especially, by integrating its former internal enemies.25

The future U.S. Treasury secretary also feared the drain of capital if Loyalists left en masse, and worried it would create obstacles to revitalizing Anglo-American trade: “Our state will feel for twenty years at least, the effects of the popular phrenzy.” Besides, if America failed to honor its obligations under the peace treaty, might not Britain do the same? Indeed, a decade later, during the negotiations over the so-called Jay Treaty with the U.S. that was designed to regulate trade, avert a future war, and resolve issues outstanding since 1783, the British government cited U.S. land seizures from Loyalists to justify why it had been maintaining military outposts in the U.S.-Canadian borderlands in breach of the 1783 accord.

New Yorkers hotly debated the relative merits of revenge and reconciliation in the immediate postwar era. The state legislature had passed a Confiscation Act in 1779 and the so-called Citation Act in 1782, which deprived Loyalists of their property and impeded British creditors’ chances to collect Patriot debts. In 1782 and 1783, as Loyalist and Patriot refugees encountered each other in large numbers for the first time in years in New York City, Patriots who had fled the British occupation demanded back rent and compensation for damage and theft. Robert R. Livingston, the chancellor (highest judicial officer) of New York, shared Hamilton’s concerns about the exodus of Loyalists and its impact on the city and state. He attributed the “violent spirit of persecution” in some Patriots to “a blind spirit of revenge & resentment,” but “in more it is the most sordid interest. One wishes to possess the house of some wretched Tory, another fears him as a rivale in his trade or commerce, & a fourth wishes to get rid of his debts by shaking of his creditor or to reduce the price of Living by depopulating the town.” In peace, as in war, Americans pursued private feuds under the thin veil of a patriotic cloak. Hamilton’s frustration with the situation is apparent in a letter he wrote to Gouverneur Morris in February 1784. New Yorkers were focusing their energies on the wrong projects, Hamilton complained: instead of improving “our polity and commerce, we are labouring to contrive methods to mortify and punish the tories and to explain away treaties.”26

In a test case that has since become famous in U.S. legal history, in 1784, Hamilton defended a rich Loyalist against the Patriot widow Elizabeth Rutgers. In 1776, Rutgers had fled New York, abandoning her family’s alehouse and brewery. By 1778, British merchants refitted the derelict brewery at a cost of £700; from 1780, they paid rent to the British Army. A fire in 1783 caused £4,000 worth of damage. At war’s end, Rutgers returned to New York City to sue one of the British merchants for £8,000 in back rent under New York’s new Trespass Act, which allowed Patriots to seek compensation from individuals who had occupied or damaged their property behind enemy lines. The Patriots had returned with a vengeance to the Loyalists’ former stronghold, and they left no one in any doubt about who was in charge.27

Hamilton argued that the wartime owners had restored the derelict property and acted properly under British martial law. He articulated what was to become the nationalist theory of federalism: international treaties and national laws were higher authorities to which all statutory and state laws had to conform; if the two conflicted, international and national law trumped state law. New York’s Trespass Act contravened the peace treaty, which prohibited punitive suits. Laying out an early version of the doctrine of judicial review, Hamilton argued that the court therefore needed to strike it down. In a split verdict, the judge granted Rutgers back rent, but only for the period up to 1780. In doing so, although he did not strike down the law, he implicitly validated Hamilton’s argument. Throughout the 1780s, Hamilton’s law practice flourished as he defended dozens of Loyalists under the Confiscation, Citation, and Trespass Acts. The radical Patriot press vilified him as a Tory, and rumors circulated of assassination plots. But when in 1787 the New York legislature repealed the Trespass Act, assemblyman Alexander Hamilton had the satisfaction of cosponsoring the bill. Practicing what he preached, Hamilton would soon appoint the former Loyalist Tench Coxe of Pennsylvania as his assistant secretary at the Treasury.28

As American communities transitioned from a decade of civil war, they each needed to reconcile competing demands—from wartime grievances in need of resolution, to yearnings for peace and reconciliation, to economic self-interest. New Haven, Connecticut, is a case in point. In the summer of 1779, Major General Sir William Tryon, formerly the royal governor of New York, had launched strikes against several Connecticut coastal towns in an (unsuccessful) attempt to draw Washington’s army out of its defensive position in the Highlands. Tryon’s British, Hessian, and Loyalist troops raided New Haven, then America’s sixth-largest town. The British considered western Connecticut a Loyalist stronghold, and a fair share of New Haven’s population, including some prominent and prosperous citizens as well as Yale College students and graduates, did not support the Revolution. Now Patriots, Loyalists, and uncommitted locals alike were forced to decide whether to take a stand, collaborate, or flee. Amid frantic looting, sexual assaults on women, and the gratuitous killing of some unarmed men, political loyalties and personal ties alike were being tested. Elizur Goodrich, a Yale senior in one of the local companies that had tried to delay the British assault, was wounded in his leg. As he looked for medical assistance, a British soldier bayoneted him. Elizur managed to escape to the house of Abiather Camp, who, though a Loyalist, was friends with the younger man’s father. Camp tended to Elizur’s bayonet wound and sheltered him from further assault. (He’d survive to become a congressman and Yale professor of law.) The Loyalist aunt of a local Patriot officer braved enemy troop visits unharmed. One man who had been unable to flee because of his wife’s illness pretended to be a friend to King George and thus successfully protected his property from looting. But a Mr. Kennedy, also a well-known Loyalist, who was said to have rejoiced at the arrival of the British, was robbed of his silver shoe buckles. When he protested this unexpected treatment, he was stabbed to death.29

Once the invaders had moved out, the physical damage at New Haven was valued at some £25,000. However, a large proportion of claims concerned the personal property of residents rather than their homes or public structures. And at least half of those losses were the result of neighbor-on-neighbor looting: Loyalists had pilfered under the cover of the British invasion; Patriots had looted and burned deserted homes, including many owned by fellow Patriots who had fled. For months afterward, citizens offered rewards for the return of goods, “[p]lundered by some of the militia” or, as they would delicately phrase it, “[l]ost…immediately after the enemy left this town.”30

After the raids, the citizens of New Haven asked themselves whom they could still trust in their community. Not only had neighbors brazenly stolen from neighbors, but a substantial number of men appeared to have remained in town during the raid without offering resistance. Later that summer, the town meeting launched a fraternization inquiry. Three dozen men gave satisfactory reasons for choosing not to flee or defend the town. Twenty men had made forgivable errors of judgment in staying behind rather than intending to “put themselves under the protection of the Enemies of the united States of America.” However, at least five men failed to give adequate reasons for their conduct during the raid. And a final dozen or so had stayed in New Haven during the raid but had either been captured by the British or had since relocated. Indeed, entire Loyalist families had left town with the British invaders, such as the wealthy Yale alumnus Joshua Chandler (whom the Patriots had previously imprisoned as a Loyalist), his wife, and their seven children, chief among them two sons who had guided the invaders to New Haven. Unlike the military commanders who had covered up the destruction of Norfolk earlier in the war, the citizens of New Haven confronted the messiness of civil war head-on while it was still raging all around them.31

In a move fairly typical of communities immediately after the war, the New Haven town meeting in 1783 voted against the return of any “Miscreants who have deserted their country’s cause, and joined the enemies of this and the United States of America, during the late contest.” But as early as 1784, elections produced mixed results: the mayor, two aldermen, and five members of the Common Council were Patriots; two aldermen and eight councillors were Loyalists; five councillors were “Flexibles but in heart Whigs,” meaning Patriots. With the local Loyalists’ political rehabilitation well under way, Ezra Stiles, president of Yale, suspected “an Endeavor silently to bring Tories into an Equality & Supremacy among the Whigs.”32

A month after those city elections, on March 8, 1784, the citizens of New Haven formed a committee to “[c]onsider the Propriety and Expediency of admitting as inhabitants of this Town persons who in the Course of the Late war adhered to the cause of Great Britain against the united States.” The actual work had evidently already been done, for the committee produced a detailed report that same day. They stressed states’ rights and emphasized that under Connecticut law it was for individual towns to decide who could live there. A “Spirit of real peace and philanthropy towards our [Loyalist] Countrymen” had guided the definitive peace treaty and the congressional recommendation that states enforce it. Since the “National Question” on which Loyalists and Patriots had differed had been settled “authoritatively in favor of the United States,” the committee recommended that New Haven admit as inhabitants any Loyalists judged to be “of fair character” and who would be “good and usefull members of Society, and faithfull citizens of this State.” But there were clear limits to forgiveness: anyone who had “committed unauthorized and lawless plundering or Murder,” and anyone who had “waged war against these United States, contrary to the laws and Usuages of Civilized Nations,” would not obtain residency or citizens’ rights.33

Evoking the same language of virtuous warfare that Congress, the army leadership, and wartime propagandists had employed throughout the conflict, the committee continued its high-minded rhetoric: “In our opinion no nation, however distinguished for prowess in arms and success in war, can be truly great, unless it is also distinguished for Justice and Magnanimity. None can properly claim to be just who violate their most solemn treaties, or to be magnanimous who persecute a conquered and submitting enemy.” A desire for revenge, however understandable in light of recent sufferings, must be laid aside for a more measured approach. Given the importance of the city’s port and of commerce to New Haven’s prosperity, welcoming Loyalists back was also economically prudent. A disgruntled President Stiles recorded in his diary: “This day Town-Meeting voted to readmit the Tories.”34

Even with the Loyalists’ reintegration proceeding apace, local preachers ensured that Patriots also kept fresh the memory of their wartime sufferings. On Independence Day in 1787, David Daggett vividly remembered Tryon’s raids:

There the unrelenting foe, with more than hellish malice, assaulted a venerable, a respectable old man, plunged a poignant dagger in his body, and left him languishing, and languishing he died!—Here one of your neighbours was in a moment struck dead!—and yonder you saw one, whom you had long known, weltering in his blood, till his agonizing struggles had stretched him a breathless corps!—Such scenes we have beheld, and such have been realized in many other towns.35

Remembering the Patriots’ sacrifice was compatible, then, with reconciliation. Indeed, the former was a necessary part of the latter, as the Revolution’s winners reminded their former opponents that they owed their reintegration to the magnanimity of their victorious, morally superior neighbors. In the wake of a violent nation-building conflict, the Loyalists’ suffering, by contrast, would not be recalled in the future story of America’s founding.

The economic argument put forward by proponents of reintegration in New Haven was also a catalyst for treaty compliance elsewhere, from New Jersey to South Carolina. Communities realized that their war-torn economies would benefit from the return of skilled and specialized professionals as well as consumers, regardless of their wartime loyalties. On the initiative of merchants, the New Jersey state assembly established Perth Amboy and Trenton as free ports, exempt from customs duties, and passed liberal citizenship legislation in the hope of attracting Loyalist refugees and merchants. Alas, only two dozen or so Loyalist merchants made the move before federal regulations prohibited free ports after 1789. At a local level, individuals who could provide a community with particular services—whether as merchants, shopkeepers, doctors, or lawyers—on the whole seemed able to reintegrate more easily. But then, Dr. Samuel Stearns, a Loyalist physician from Paxton, Pennsylvania, who returned there in the fall of 1784, was arrested and imprisoned for nearly three years. Not every professional was welcomed home with open arms.36

Those leaders of the early United States who, like Hamilton, favored a policy of reconciliation and reintegration worked with the states to repeal discriminatory laws that undermined the peace accord. New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey, the Carolinas, and Georgia permitted many Loyalists to return over the course of the 1780s. Their confiscated property was restored and they earned citizenship rights. Eventually even Benjamin Franklin, who in Paris had most strongly opposed any concessions to the Loyalists, supported their reintegration as president of the Supreme Executive Council (or quasi governor) of Pennsylvania, where a 1786 citizenship law allowed individuals who had refused to take Patriot oaths during the Revolution to become citizens upon swearing a loyalty oath. However, Franklin’s newfound magnanimity did not extend to his son. En route back from France to America in the summer of 1785, Benjamin had met with William for a few days in Southampton, England. The father used their first encounter in years to force his son to sell him his American landholdings in settlement of debts owed. In 1788, Benjamin effectively disinherited William for the “part he acted against me in the late War.”37

If the Franklins were never reconciled, remnants of official anti-Loyalist policies survived in many states at least until the turn of the new century. So did unofficial persecution. Throughout the 1780s and ’90s, there were “feverish witch hunts for traitors who allegedly sought to reverse the verdict of the war,” as Hamilton’s biographer Ron Chernow has put it. Until the early nineteenth century, anti-Loyalist sentiment also remained a useful tactical weapon in elections. Yet, despite such undercurrents of animosity, the founding generation did gradually integrate their new nation.38

Among the returnees experiencing harmonious homecomings were now-forgotten Loyalists like Mary Robie, who in July 1784 moved back to Ward Chipman’s native Marblehead, Massachusetts: “We are hardly a minute alone,” Mary reported happily, “continually some old acquaintance is calling to congratulate us.” Her family’s former debtors selectively paid off loans. Mary encouraged her husband, Thomas, to return, too, and open a retail store, considering that the wartime discord was already “buried in total oblivion[;] we hear every day of people who wish to return, but of none that object to it,” as locals were “both gentle & simple.” By 1787, Mary was running her own dry goods store; Thomas is documented as a resident by 1791.39

In Poughkeepsie, a community in rural New York where wartime allegiances had been divided, but also unstable and malleable, at least twenty-seven Loyalists had had their property confiscated. Twenty more had spent some part of the war in prison; another dozen or so went into exile in Canada. In May 1783, Poughkeepsie’s inhabitants formed committees, as one man described the tense situation, to “prevent the plunderers, and Murderers (which now daringly attempt to Schelter themselves among the no less rascially Cru who have hitherto been distinguishd as peaceable Tories) from Working them selves into the company of the Worthy Citizens.” One particularly notorious Loyalist received death threats to discourage him from returning to practice law. But eventually the community integrated the majority of those among their families and neighbors who had previously offered vocal opposition to, or less than consistent support for, the Revolution—although, crucially, all but one of these were politically ostracized and never again able to obtain even the most lowly local offices.40

Elsewhere, those perceived to have been only moderately offensive Loyalists were reintegrated fairly comprehensively within a decade or so of the war’s conclusion. Roeloff Josiah Eltinge, a shopkeeper in the small town of New Paltz in the rural Hudson Valley, had been tried by a Revolutionary committee in 1776 for refusing to accept Continental currency at his family’s general store. Following two years in various prisons, Eltinge declined a final chance to take a Patriot oath of allegiance in 1778 and was banished to the British lines in New York City. In May 1784, Eltinge, along with two dozen other cast-out New York Loyalists, was permitted to return home. Eltinge—who had never taken up arms for the British, and whose property had not been confiscated—resumed his business in New Paltz; by the 1790s, he was sufficiently rehabilitated to serve in elected local office. By then, New York had repealed the 1784 act that had barred from voting and holding office any men who had served with the British, outfitted a ship, left the state, or otherwise joined the enemy; in 1792, the state finally lifted the banishment of all New York Loyalists.41

Even some of the more prominent Loyalists succeeded in being gradually reintegrated, and eventually assumed public responsibilities. Andrew Bell, a Loyalist landowner and lawyer from Perth Amboy in New Jersey, served during the Revolution as confidential secretary to Sir Henry Clinton and Sir Guy Carleton. Andrew also saw military action, including in the Battle of Monmouth in 1778. The following year Andrew’s sister Cornelia married New Jersey’s attorney general William Paterson. Cornelia’s father objected to her marriage to a leading Patriot, but Paterson and Andrew Bell both promised to tolerate Cornelia’s connections; Paterson even facilitated the siblings’ illegal wartime correspondence. At the same time, as one of the state’s key legal officers responsible for prosecuting Loyalists, Paterson indicted Andrew Bell in absentia and started the process by which the property he had inherited from his father would be confiscated. Neither Andrew nor Cornelia seemed to waver in their opposing political convictions, but neither did they attempt to convert each other. One of Cornelia’s most prized possessions was a miniature portrait her brother sent her of himself: holding and wearing the intimate representation connected Cornelia closely to Andrew, at the same time as it reminded her sorely of their separation.42

When peace came, Andrew pondered his options. Should he stay in America, where his prospects were “but small,” or should he go into exile and hope for British compensation for his loyal service? He weighed economic self-interest against the emotional cost of “leaving my dear relations and friends.” In July 1783, the siblings were finally reunited after seven years: the three days were “the most valued of my whole life,” reflected Andrew, grateful that his brother-in-law had permitted the meeting. In Andrew’s last known letter to Cornelia, he later asked her to solicit her husband’s help in obtaining documentation to support his claim for British compensation; Paterson did indeed assist with valuations. But a few weeks later, Cornelia died after giving birth to a son; she was twenty-eight. In spring 1784, her widower, William—who would go on to represent New Jersey at the Constitutional Conventions and serve the state as senator and governor—encouraged Andrew to return to his native New Jersey and meet his deceased sister’s children. Bell did indeed resettle in Perth Amboy, where he became a successful merchant. His integration proceeded apace, so that from 1806 until his death in 1842 he even served as surveyor general for the East Jersey proprietors.

Other Loyalists reactivated their prewar connections with men who had since risen to leadership positions in the United States. The New York Loyalist lawyer Peter Van Schaack had been a classmate, at King’s College, of later Founding Fathers such as John Jay, Gouverneur Morris, and Robert R. Livingston. After 1774, Van Schaack first helped administer the Continental Association but opposed independence—as, initially, did his friend John Jay. When he refused to swear an oath of allegiance in 1778, Van Schaack went into exile in England. In 1782, he sought reconciliation with Jay, then serving as a U.S. diplomat in Europe. (Jay’s own family, it’s worth remembering, included Loyalists.) Jay explained to Van Schaack that, “as an independent American, I considered all who were not for us, and you among the rest, as against us: yet be assured that John Jay did not cease to be a friend to Peter Van Schaack.” By the time the two men were reunited in London in October 1783, Van Schaack had become convinced that the British political system was corrupt; finally, he, too, embraced American independence. When Van Schaack returned to New York City in 1785, Jay awaited him at the pier; their rekindled friendship would endure for another four decades. With both his citizenship rights and his previously revoked law license restored, Van Schaack soon practiced the law again. Although Van Schaack did not hold political office—unlike some prominent ex-Loyalists who rose to state or even national positions, such as Tench Coxe—he advised New York officials on the state’s evolving judicial system; he also taught dozens of aspiring lawyers at his home, even after going blind in 1792. As the country celebrated half a century of independence in 1826, Van Schaack received a doctorate in law from Columbia College.43

And yet, as both the Revolution’s winners and, increasingly, its losers helped build the postwar United States, scars continued to mark the deep divisions that so recently had rent American society.