Map: Ruin Pubs in the Seventh District

Map: Andrássy Út Hotels & Restaurants

Map: Pest Town Center Hotels & Restaurants

Map: Buda Hotels & Restaurants

Budapest (locals say “BOO-daw-pesht”) is a unique metropolis at the heart of a unique nation. Here you’ll find experiences like nothing else in Europe: Feel your stress ebb away as you soak in hundred-degree water, surrounded by opulent Baroque domes...and by Speedo- and bikini-clad Hungarians. Ogle some of Europe’s most richly decorated interiors, which echo a proud little nation’s bygone glory days. Perk up your ears with a first-rate performance at one of the world’s top opera houses—at bargain prices. Ponder the region’s bleak communist era as you stroll amid giant Soviet-style statues designed to evoke fear and obedience. Try to wrap your head around Hungary’s colorful history...and your tongue around its notoriously difficult language. Dive into a bowl of goulash, the famous paprika-flavored peasant soup with a kick. Go for an after-dinner stroll along the Danube, immersed in a grand city that’s bathed in floodlights.

Europe’s most underrated big city, Budapest can be as challenging as it is enchanting. The sprawling Hungarian capital is a city of nuance and paradox—cosmopolitan, complicated, and tricky for the first-timer to get a handle on. Think of Budapest as that favorite Hungarian pastime, chess: It’s simple to learn...but takes a lifetime to master. This chapter is your first lesson. Then it’s your move.

Budapest demands at least two full days—and that assumes you’ll be selective and move fast. To slow down and really dig into the city, give it a third or fourth day. Adding more time opens up various day-trip options.

Budapest is quite decentralized: Plan your day ahead to minimize backtracking. Just about everything is walkable, but distances are far, and public transit can save valuable time.

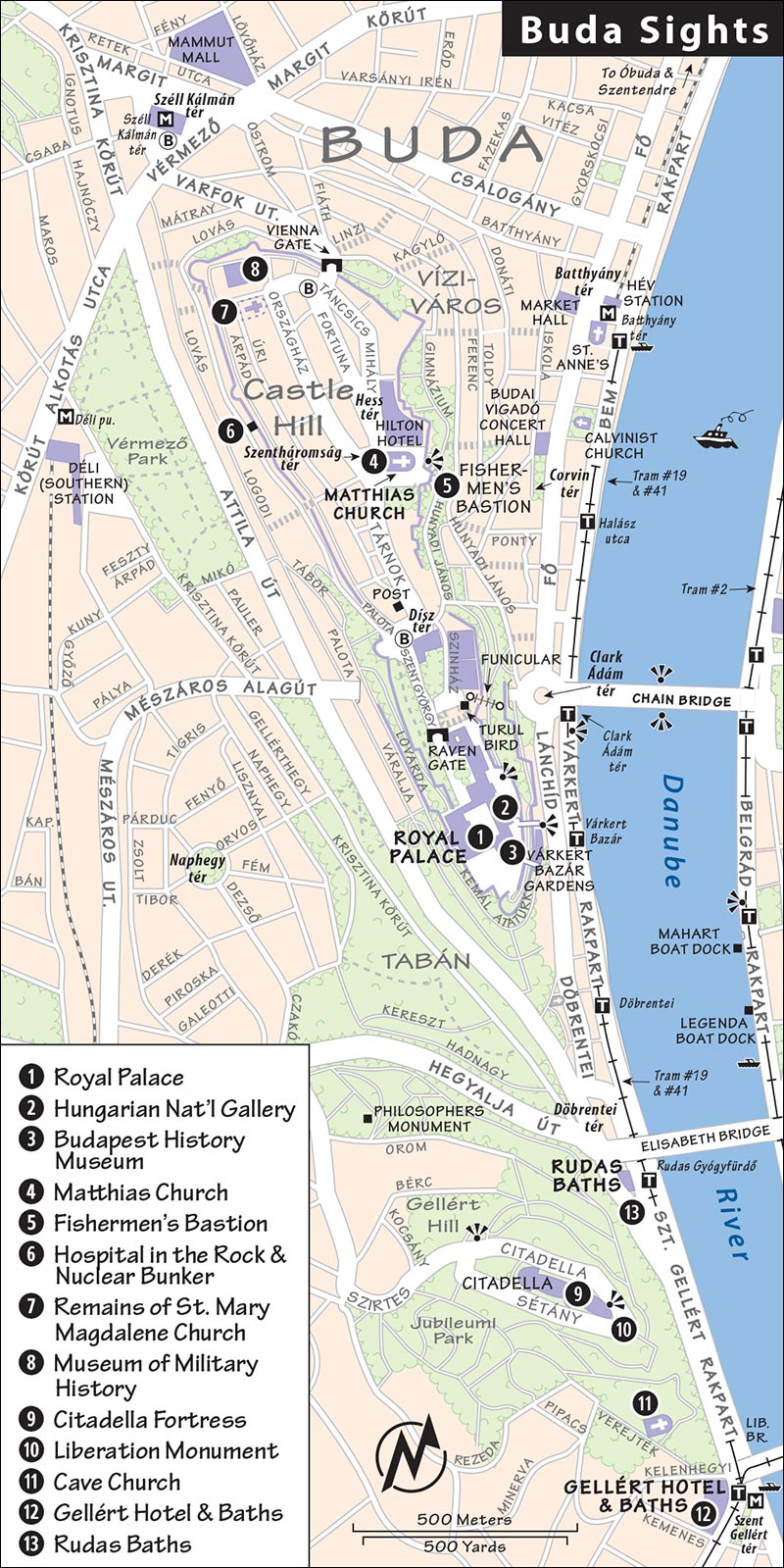

When divvying your time between Buda and Pest, keep in mind that (aside from the Gellért and Rudas Baths) Buda’s sightseeing is mostly concentrated on Castle Hill, and can easily be done in less than a day, while Pest deserves as much time as you’re willing to give it. Save relatively laid-back Buda for when you need a break from the big city.

Below are some possible plans, depending on the length of your trip. Note that these very ambitious itineraries assume you want to sightsee at a speedy pace. In the evening, you have a wide range of options (detailed under “Entertainment in Budapest” on here, and “Nightlife in Budapest” on here): enjoying good restaurants, taking in an opera or concert, snuggling on a romantic floodlit river cruise, relaxing in a thermal bath, exploring the city’s unique ruin pubs, or simply strolling the Danube embankments and bridges.

Spend Day 1 in Pest: Begin at the Parliament and stroll through Leopold Town, then walk through Pest town center to the Great Market Hall. From there, circle around the Small Boulevard to Deák tér; if you’re not wiped out yet, walk up Andrássy út to Heroes’ Square and City Park. Or, if you’re exhausted already, just take the M1/yellow Metró line to Hősök tere, ogle the Heroes’ Square statues and Vajdahunyad Castle, and reward yourself with a soak at Széchenyi Baths. (Note that this schedule leaves virtually no time for entering museums, though you might be able to fit in one or two big sights; the most worthwhile are the Parliament—for which you should book tickets ahead online—the Opera House, the Great Synagogue, or the House of Terror.)

On the morning of Day 2, tackle any Pest sights you didn’t have time for yesterday (or take the bus out to Memento Park). After lunch, ride bus #16 from Deák tér to Buda’s Castle Hill. Finally, head back to Pest for some final sightseeing and dinner.

Your first day is for getting your bearings in Pest. Begin by strolling through Leopold Town (including a tour of the Parliament—book tickets ahead online). Next, walk up Andrássy út (including touring the Opera House and/or the House of Terror) to Heroes’ Square and City Park. End your day with a soak at the Széchenyi Baths.

On Day 2, delve deeper into Pest, starting with a stroll through the town center. After visiting the Great Market Hall, you can cross the river to Buda for a soak at the Gellért or Rudas Baths, or circle around the Small Boulevard to see the National Museum and/or Great Synagogue.

On Day 3, use the morning to see any remaining sights, then ride from Deák tér out to Memento Park on the park’s 11:00 direct bus. On returning, grab a quick lunch and take bus #16 from Deák tér to Castle Hill.

With a fourth day, spread the Day 1 activities over more time, and circle back to any sights you’ve missed so far.

Budapest is huge, with nearly two million people. Like Vienna, the city was built as the head of a much larger empire than it currently governs. But the city is surprisingly easy to manage once you get the lay of the land and learn the excellent public transportation network. Those who are comfortable with the Metró, trams, and buses have the city by the tail (see “Getting Around Budapest” on here).

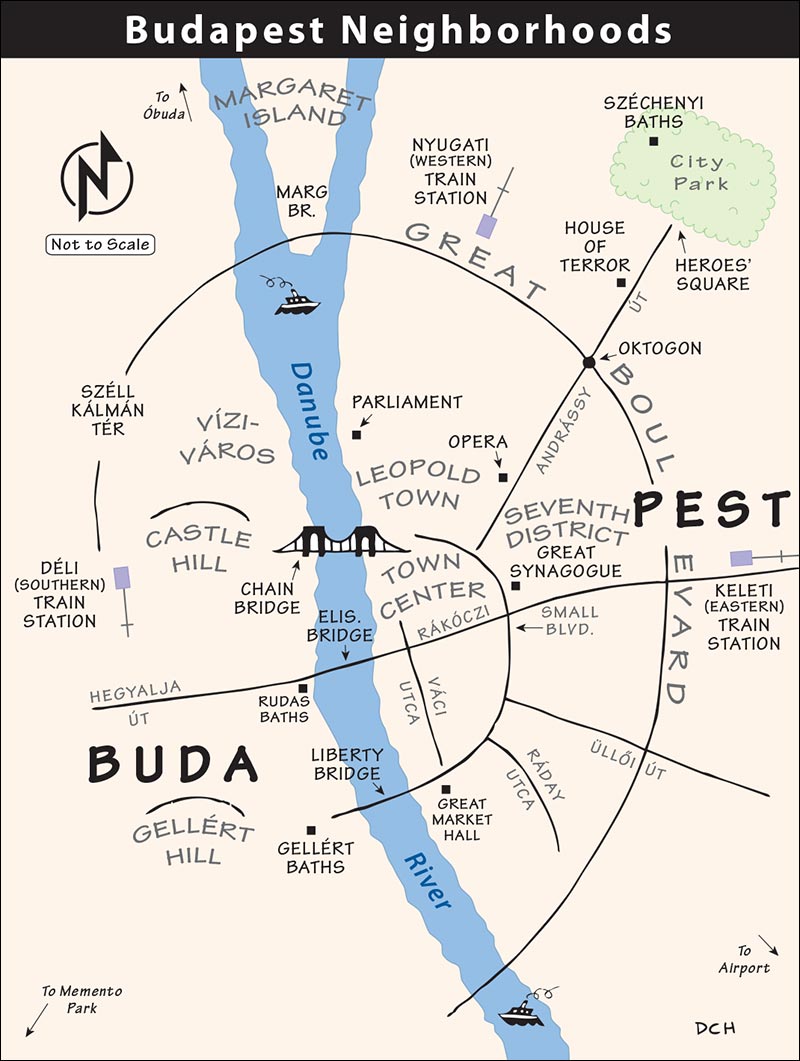

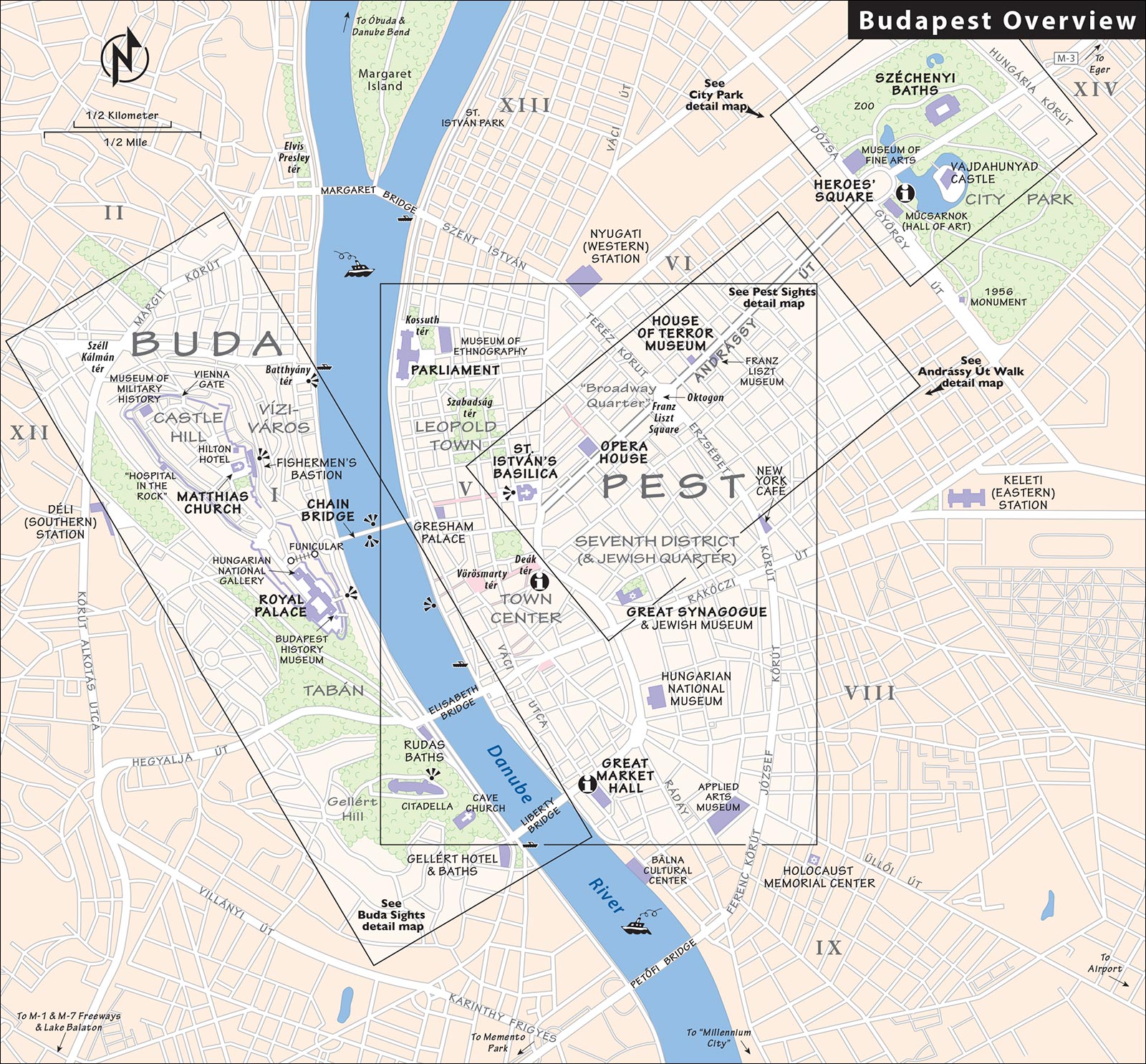

The city is split down the center by the Danube River. On the east side of the Danube is flat Pest (pronounced “pesht”), and on the west is hilly Buda. A third part of the city, Óbuda, sits to the north of Buda.

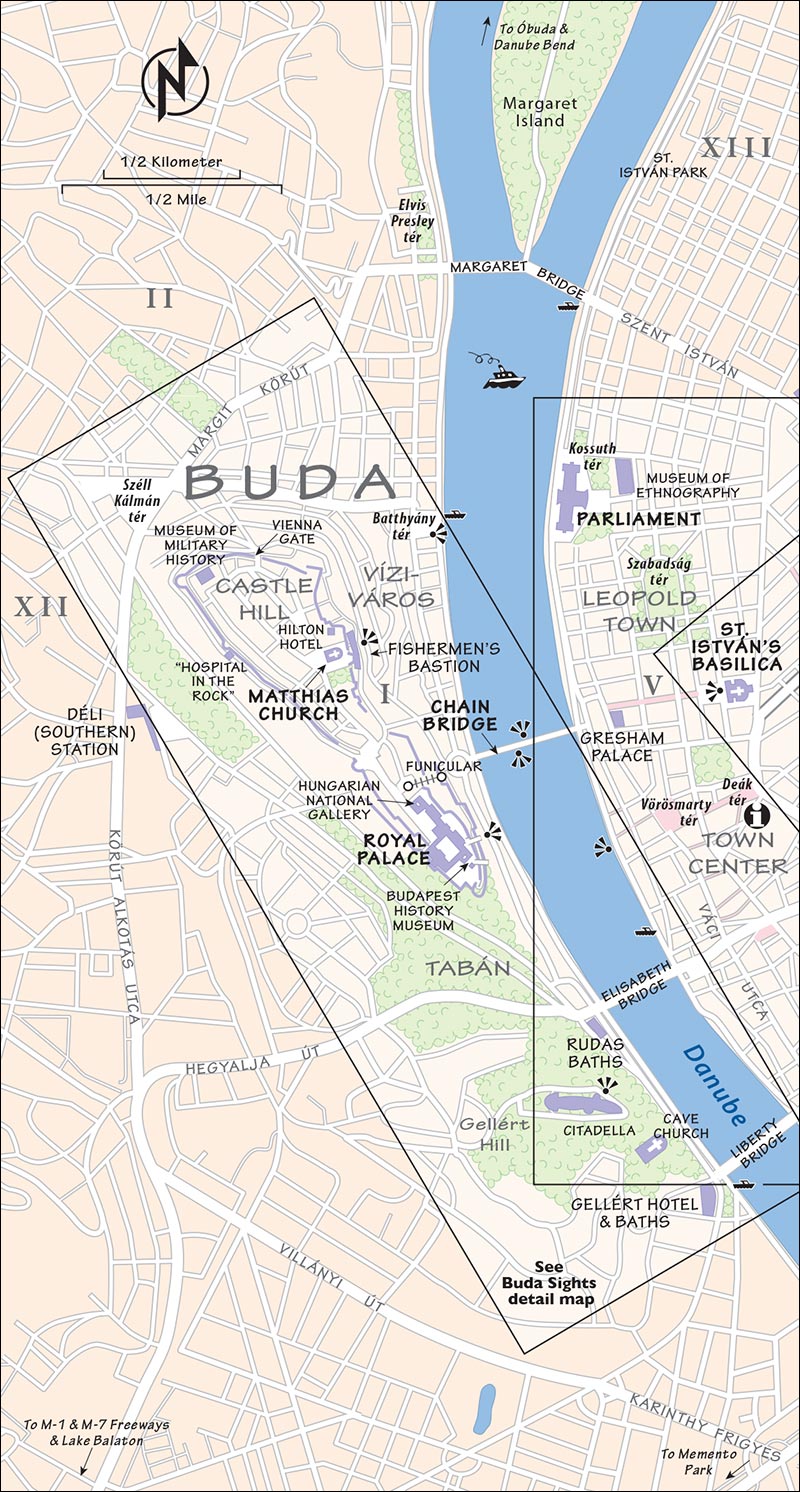

Buda: Buda is dominated by Castle Hill (packed with tourists by day, dead at night). The pleasant Víziváros (“Water Town”; VEE-zee-vah-rohsh) neighborhood is between the castle and the river; nearby is the square called Batthyány tér (a handy hub for the Metró—M2/red line—plus tram lines and the HÉV suburban railway). To the south is the taller, wooded Gellért Hill, capped by the Liberation Monument, with a pair of thermal baths at its base—Gellért and Rudas.

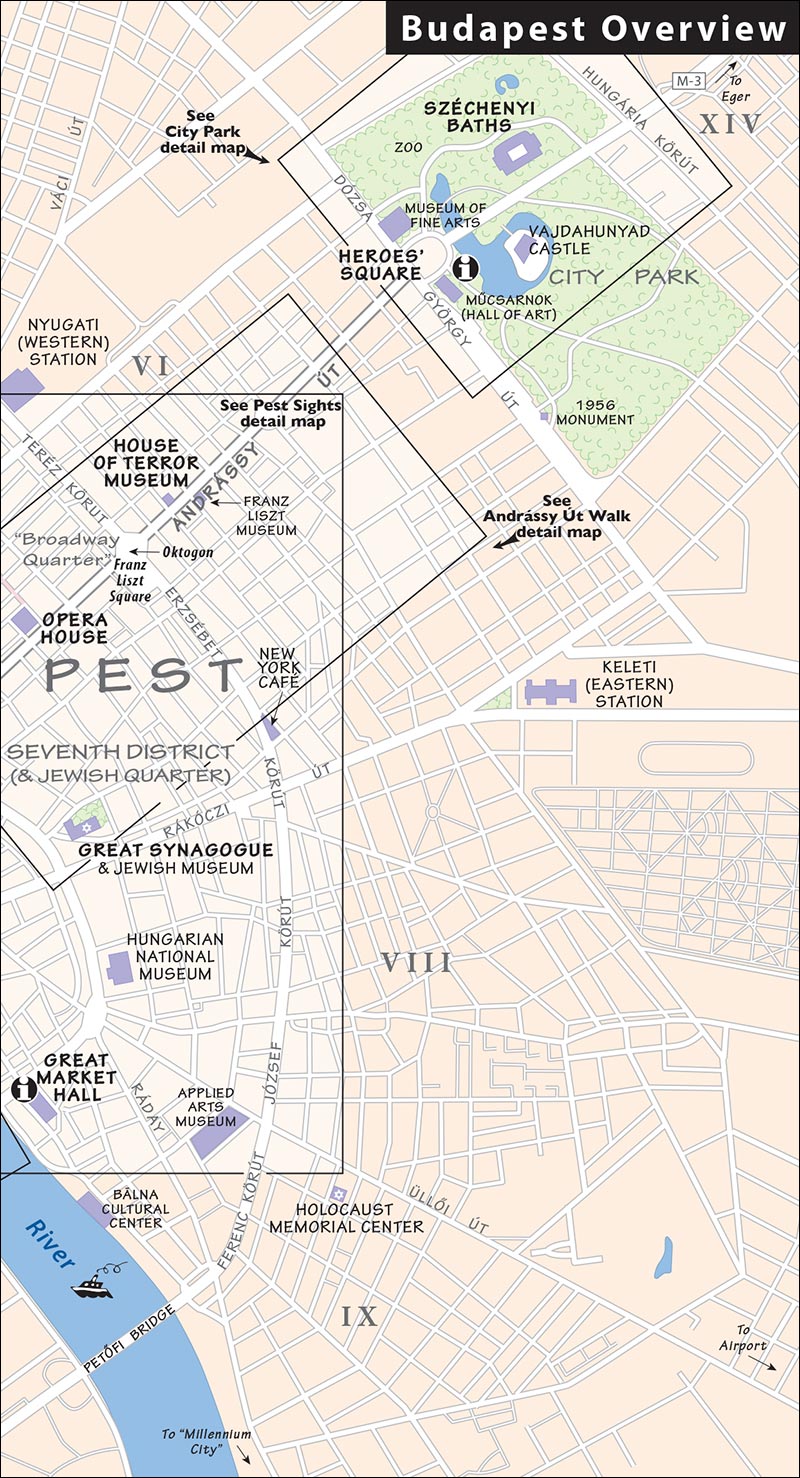

Pest: Just across the river from Castle Hill, “Downtown” Pest is divided into two sections. The more polished northern half, called Leopold Town (Lipótváros), surrounds the giant Parliament building. This is the governmental, business, and banking district (sleepy after hours). The southern half, the grittier and more urban-feeling Town Center (Belváros, literally “Inner Town”), is a thriving shopping, dining, nightlife, and residential zone that bustles day and night. Major landmarks here include the vast Great Market Hall and the famous (and overrated) Váci utca shopping street.

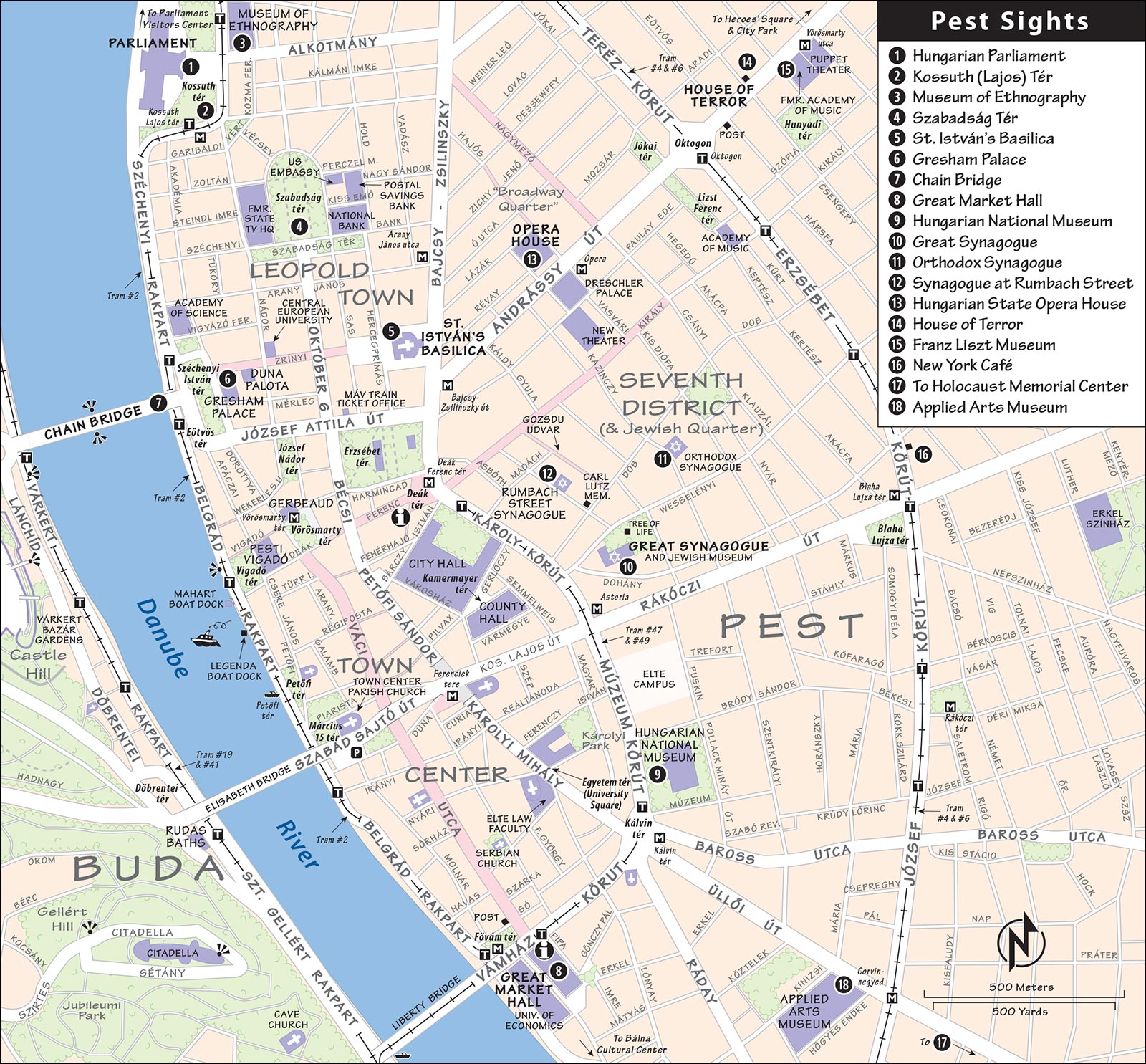

Additional key sights lie along the Small Boulevard ring road (connected by trams #47 and #49), including—from north to south—the Great Synagogue (marking the start of the Jewish Quarter, which feels a bit rundown but features several Jewish sights, as well as the Seventh District, a hopping nightlife zone with cool “ruin pubs”), the National Museum, and the Great Market Hall. Even more points of interest are spread far and wide along the Great Boulevard ring road (circled by trams #4 and #6), including Margaret Island (the city’s playground, in the middle of the Danube), the Nyugati/Western train station, the prominent Oktogon intersection (where it crosses Andrássy út), the opulent New York Café (with the Keleti/Eastern train station just up the street), and the intersection with Üllői út, near the Holocaust Memorial Center and Applied Arts Museum.

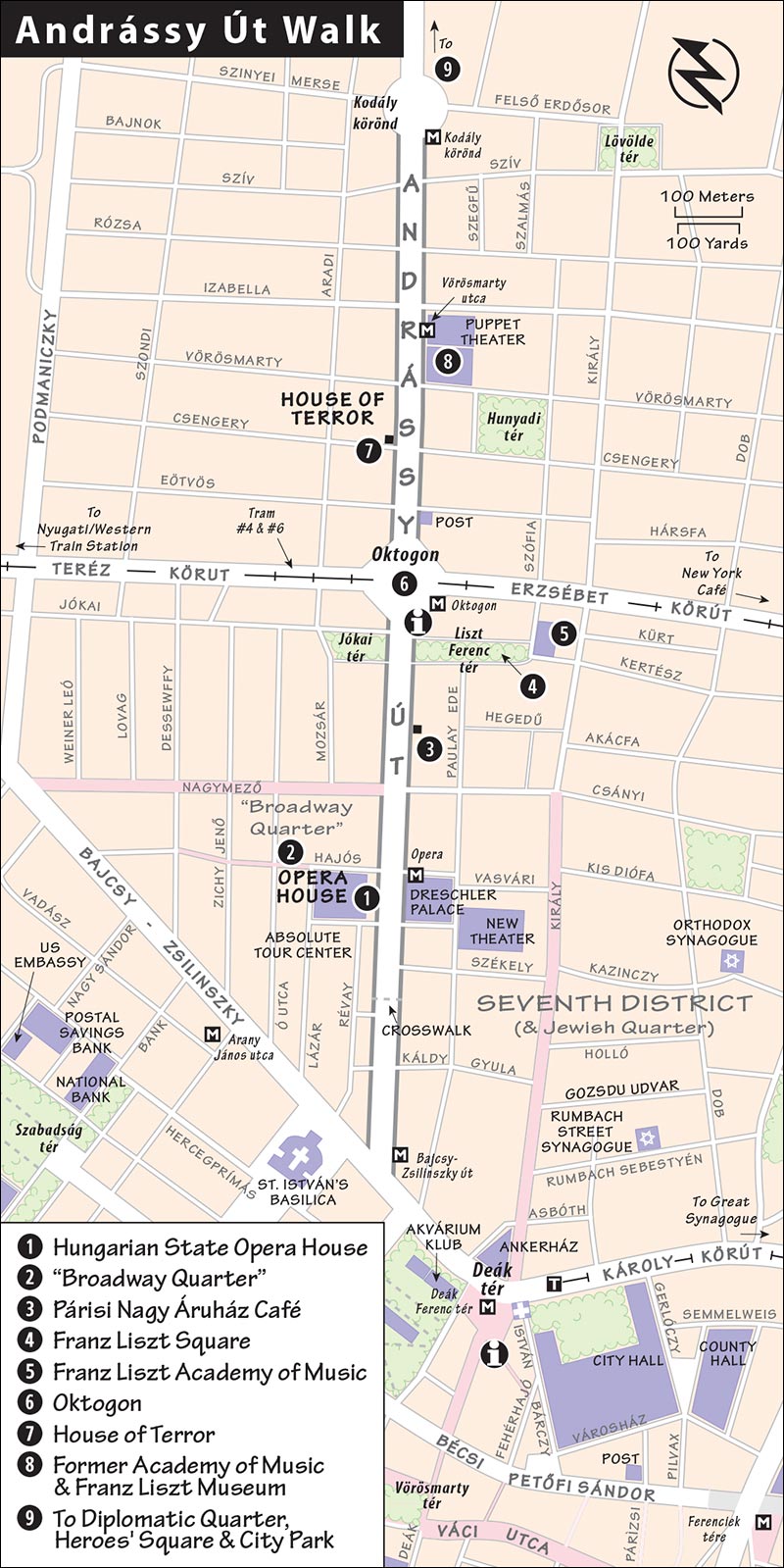

Roads: The Town Center is hemmed in by the first of Pest’s four concentric ring roads (körút). The innermost ring is called the Kiskörút, or “Small Boulevard.” The next ring, several blocks farther out, is called the Nagykörút, or “Great Boulevard.” These ring roads change names every few blocks, but they are always called körút. Arterial boulevards, called út, stretch from central Pest into the suburbs like spokes on a wheel. One of these boulevards, Andrássy út, begins near Deák tér in central Pest and heads out to Heroes’ Square and City Park; along the way it passes some of the city’s best eateries, hotels, and sights (Opera House, House of Terror).

Bridges: Buda and Pest are connected by a series of characteristic bridges. From north to south, there’s the low-profile Margaret Bridge (Margit híd, crosses Margaret Island), the famous Chain Bridge (Széchenyi Lánchíd), the white and modern Elisabeth Bridge (Erzsébet híd), and the green Liberty Bridge (Szabadság híd). Four more bridges lie beyond the tourist zone: the Petőfi and Rákóczi bridges to the south, and Árpád and Megyeri bridges to the north.

Districts: Budapest uses a district system (like Paris and Vienna). There are 23 districts (kerület), identified by Roman numerals. For example, Castle Hill is in district I, central Pest is district V, and City Park is in district XIV. Addresses often start with the district number (as a Roman numeral).

The city of Budapest runs several official TIs (www.budapestinfo.hu, tel. 1/438-8080). The main branch is at Deák tér, a few steps from the M2 and M3 Metró station (daily 8:00-20:00, free Wi-Fi, Sütő utca 2, near the McDonald’s, district V). Other locations include Heroes’ Square (in the ice rink building facing Vajdahunyad Castle, daily 9:00-19:00), in a small kiosk just inside the main entrance of the Great Market Hall (Mon 6:00-17:00, Tue-Fri 6:00-18:00, Sat 6:00-15:00, closed Sun), and in both terminals at the airport (TI at Terminal 2A open daily 8:00-22:00; TI at Terminal 2B open daily 10:00-22:00). In the busy summer months, TI “mobile info points” set up in highly trafficked areas (look for the teal-and-white umbrellas).

The helpfulness of Budapest’s TIs can vary, but all offer a nice variety of free, useful publications, including a good city map, the information-packed Budapest Guide booklet, and various events planners. At any TI, you can collect a pile of other free brochures (for sights, bus tours, and more) and buy a Budapest Card. Be aware that many for-profit agencies masquerade as “TIs” or “info points” (such as in the train stations); these are unofficial, but some—such as the one in the white kiosk on Castle Hill, near the Matthias Church—can be helpful in a pinch.

Sightseeing Passes: The Budapest Card includes free use of all public transportation, free walking tours of Buda and Pest, free admissions to a handful of sights (including the National Museum, National Gallery, and Memento Park), and 10-50 percent discounts on many other major museums and attractions (4,900 Ft/24 hours, 7,900 Ft/48 hours, 9,900 Ft/72 hours; includes handy 100-page booklet with maps, updated hours, and brief museum descriptions; www.budapest-card.com). If you take advantage of the included walking tours, the Budapest Card can be a good value for a very busy sightseer—do the arithmetic.

Absolute Tour Center: This office, conveniently located near Andrássy út (behind the Opera House at Lázár utca 16) can also dispense tourist information questions. They also have free Wi-Fi, bike rental, secondhand books, and information on their walking, bike, and Segway tours—all described later, under “Tours in Budapest” (sporadic hours, usually open daily 9:00-20:00, until 19:00 Nov-March, tel. 1/269-3843, mobile +3620-929-7506, www.absolutetours.com).

Budapest has three major train stations (pályaudvar, abbreviated pu.): Keleti (“Eastern”) station, Nyugati (“Western”) station, and Déli (“Southern”) station. Before departing from Budapest, it’s essential to carefully confirm which station your train leaves from.

The Keleti/Eastern train station and the Nyugati/Western train station are both cavernous, slightly rundown, late-19th-century Erector-set masterpieces in Pest. The Déli/Southern train station—behind Castle Hill in Buda—mingles its dinginess with modern, concrete flair.

All three stations are seedy and overdue for renovation. This makes them a bit intimidating—not the most pleasant first taste of Budapest. But once you get your bearings, they’re easy to navigate. A few key words: pénztár or jegypénztár is ticket window, vágány is track, induló vonatok is departures, and érkező vonatok is arrivals. At all stations, access to the tracks is monitored: You might have to show your ticket to reach the platforms (though this is loosely enforced).

The taxi stands in front of each train station are notorious for ripping off tourists; it’s better to call for a taxi (or, better yet, stick to public transit). For tips on this—and on using the Metró system to connect into downtown Budapest—see “Getting Around Budapest” on here.

Keleti train station (Keleti pu.) is just south of City Park, east of central Pest. The station faces a pretty, split-level, newly renovated plaza called Baross tér, with stops for two different Metró lines (M2/red and M4/green).

On arrival, go to the front of long tracks 6-9 to reach the exits and services. Several travel agencies masquerading as TIs cluster near the head of the tracks. A handy OTP ATM is just to the left of the main door (other ATMs you see inside the station have rip-off rates—but two more legitimate ATMs are inside banks that face the square out front). Train ticket machines are also just inside the main door. There’s no official TI at the station, but the railroad runs a customer service office with train advice and basic city info (near the front of track 9, in the left corner, near the ATM).

Along track 6, from back to front, you’ll see a side door (leading to a beautifully restored arrivals hall, and an exit to a taxi stand), Interchange exchange booth (with bad rates—use the OTP ATM instead), international ticket windows (nemzetközi jegypénztár), grubby gyro stands, and the classy Baross Restaurant. Pay WCs are down the hall past the gyro places. Across the main hall, more services run along track 9, including domestic (“inland”) ticket windows and lockers. The big staircase at the head of the tracks leads down to more domestic ticket windows, WCs, telephones, and more lockers.

To get into the city center, the easiest option is to take the Metró: Heading down the main stairs where the tracks dead-end, you’ll pass through a ticket area, and then (on your right) a public transit ticket and information office (a handy place to pick up a transit ticket, if you need one). Just beyond that, the underpass opens up: Turn left to reach the M2/red Metró line, or right to reach the M4/green Metró line.

I’d avoid taxis—the ones waiting alongside the station (through the exit by track 6) are likely to be dishonest, but you can try asking for a rough estimate: the fair rate to downtown should be no more than 2,000 Ft. If you must take a taxi, it’s far more reliable to phone for one (call 211-1111 or 266-6666, tell the English-speaking dispatcher where you are, and go outside to meet your taxi).

Nyugati train station (Nyugati pu.) is the most central of Budapest’s stations, facing the Great Boulevard on the northeast edge of downtown Pest.

Most trains use the shorter tracks 1-9, which are set back from the main entrance. From the head of these tracks, use the stairs or escalator just inside the doors to reach an underpass and the Metró (M3/blue line). Or exit straight ahead into a parking lot with buses, taxis, and—around to the right—the WestEnd City Center shopping mall. (The useful trams around the Great Boulevard are outside the main door, at the head of the longer tracks 10-13—see below.) Note that the taxi drivers here are often crooked—it’s far better to call for your own cab (see instructions and taxi phone numbers described previously for Keleti station).

The longer tracks 10-13 extend all the way to the main entrance. Ticket machines line the tracks. Ticket windows are through an easy-to-miss door by platform 13 (marked jegypénztár and információ; once you enter the ticket hall, international windows are in a second room at the far end—look for nemzetközi jegypénztár). Lockers are down the hall next to the international ticket office, on the left. An ATM is just inside the main door, on the right.

From the head of tracks 10-13, exit straight ahead out the main entrance and you’ll be on Teréz körút, the very busy Great Boulevard ring road. In front of the building is the stop for the handy trams #4 and #6 (which zip around the Great Boulevard); to the right are stairs leading to an underpass (use it to avoid crossing this busy intersection, or to reach the Metró’s M3/blue line); and to the left is the classiest Art Nouveau McDonald’s on the planet, filling the station’s former waiting room. (Seriously. Take a look inside.)

In the late 19th century, local newlyweds caught the train at Déli train station (Déli pu.) for their honeymoon in Venice. Renovated by the heavy-handed communists, today the station—tucked behind Castle Hill on the Buda side—is dreary, dark-stone, smaller, and more modern-feeling than the other train stations. From the tracks, go straight ahead into the vast, empty-feeling main hall, with well-marked domestic and international ticket windows at opposite ends. A left-luggage desk is outside beyond track 1. Downstairs, you’ll find several shops and eateries, and access to the very convenient M2/red Metró line, which takes you to several key points in town: Batthyány tér (on the Buda embankment, at the north end of the Víziváros neighborhood), Deák tér (the heart of Pest, with connections to two other Metró lines), and Keleti train station (where you can transfer to the M4/green Metró line).

Budapest’s Liszt Ferenc Airport is 10 miles southeast of the center (airport code: BUD, tel. 1/296-7000, www.bud.hu). Many Hungarians still call the airport by its former name, “Ferihegy.” The airport’s lone passenger terminal is called “Terminal 2” (“Terminal 1” closed in 2012). The terminal has two adjacent parts, which you can easily walk between in just a few minutes: the smaller Terminal 2A is for flights from EU/Schengen countries (no passport control required), while Terminal 2B is for flights from other countries. Both sections have ATMs and TI desks (open daily 8:00-23:00 in 2A, and daily 10:00-22:00 in 2B). Car rental desks are in the arrivals area for 2B.

Getting Between the Airport and Downtown Budapest: The fastest door-to-door option is to take a taxi. Főtaxi has a monopoly at the taxi stand out front; figure about 6,500 Ft to downtown, depending on traffic.

The airport shuttle minibus is cheaper for solo travelers, but two people will pay only a few dollars more to share a taxi (3,900 Ft/1 person, 4,900 Ft/2 people; minibus ride to any hotel in the city center takes about 30-60 minutes depending on hotel location, plus waiting time; tel. 1/550-0000, www.minibud.hu; if arranging a minibus transfer to the airport, call at least 24 hours in advance). Because they prefer to take several people at once, you may have to wait awhile at the airport for a quorum to show up (about 20 minutes in busy times, up to an hour when it’s slow—they can give you an estimate).

Finally, there’s the cheap but slow public bus #200E. This runs in about 25 minutes to the Kőbánya-Kispest station on the M3/blue Metró line; from there, take the Metró the rest of the way into town (entire journey covered by basic 530-Ft transit ticket, allow about an hour total for the trip to the center).

Getting Between the Airport and Eger: Eger makes an enjoyable small-town entry point in Hungary for getting over your jet lag. Unfortunately, there is no direct connection there from Budapest’s airport. The easiest plan is to ride the airport shuttle minibus to Budapest’s Keleti/Eastern train station, then catch the Eger-bound train from there. Or, to save a little money, you could take public bus #200E to Kőbánya-Kispest, ride the M3/blue Metró line to Deák tér, and transfer to the M2/red Metró line, which stops at both Keleti station (for the train to Eger) and Stadionok (for the bus to Eger).

Avoid driving in Budapest if you can—roads are narrow, and fellow drivers, bikes, and pedestrians make the roads feel like an obstacle course. Especially during rush hour (7:00-9:00 and 16:00-18:00), congestion is maddening, and since there’s no complete expressway bypass, much of the traffic going through the city has to go through the city—sharing the downtown streets with local commuters. The recent wave of roadwork and other construction around Budapest only complicates matters. Signage can be confusing. Don’t drive down roads marked with a red circle, or in lanes marked for buses; these can be monitored by automatic traffic cameras, and you could be mailed a ticket.

There are three concentric ring roads, all of them slow: the Small Boulevard (Kiskörút), Great Boulevard (Nagykörút), and outermost Hungária körút, from which highways and expressways spin off to other destinations. Farther out, the M-0 expressway makes a not-quite-complete circle around the city center, helping to divert some traffic.

Parking: While in Budapest, unless you’re heading to an out-of-town sight (such as Memento Park), park the car at or near your hotel and take public transportation. Public street parking costs 175-525 Ft per hour (pay in advance at machine and put ticket on dashboard—watch locals and imitate). Within the Great Boulevard, it’s generally free to park from 20:00 until 8:00 the next morning (farther out, it’s free after 18:00). But in some heavily touristed areas, you may have to pay around the clock. Always check signs carefully, and confirm with a local (such as your hotelier) that you’ve parked appropriately. Also, be sure to park within the lines—otherwise, your car is likely to get “booted” (I’ve seen more than one confused tourist puzzling over the giant red brace on his wheel). A guarded parking lot is safer, but more expensive (figure 3,000-4,000 Ft/day, ask your hotel or look for the blue Ps on maps). As rental-car theft can be a problem, ask at your hotel for advice.

Exchange Rate: 275 Ft = about $1, €1 = about $1.10

Country Calling Code: 36 (see here for dialing instructions).

Rip-Offs: Budapest is quite safe, especially for a city of its size. Occasionally tourists run into con artists or pickpockets; as in any big city, wear a money belt and secure your valuables in touristy places and on public transportation.

Restaurants on the Váci utca shopping street are notorious for overcharging tourists. Anywhere in Budapest, avoid restaurants that don’t list prices on the menu. Make a habit of checking your bill carefully. Most restaurants add a 10-12 percent service charge; if you don’t notice this, you might accidentally double-tip (for more on tipping, see 1080). Also, at Váci utca and at train stations, avoid using the rip-off currency exchange booths (such as Interchange or Checkpoint). You’ll do much better simply getting cash from an ATM associated with a major bank (including OTP, MKB, K&H, and various big international banks).

Budapest’s biggest crooks? Unscrupulous cabbies. For tips on outsmarting them, see “Getting Around Budapest—By Taxi” on here. Bottom line: Locals always call for a cab, rather than hail one on the street or at a taxi stand. If you’re not comfortable making the call yourself, ask your hotel or restaurant to call for you.

Sightseeing Tips: Budapest boomed in the late 19th century, after it became the co-capital of the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most of its finest buildings (and top sights) date from this age. To appreciate an opulent interior—a Budapest experience worth ▲▲▲—prioritize touring either the Parliament or the Opera House, depending on your interests. The Opera tour is more crowd-pleasing, while the Parliament tour is grander and a bit drier (with a focus on history and parliamentary process). Seeing both is also a fine option. “Honorable mentions” go to the interiors of St. István’s Basilica, the Great Synagogue, New York Café, and both the Széchenyi and the Gellért Baths.

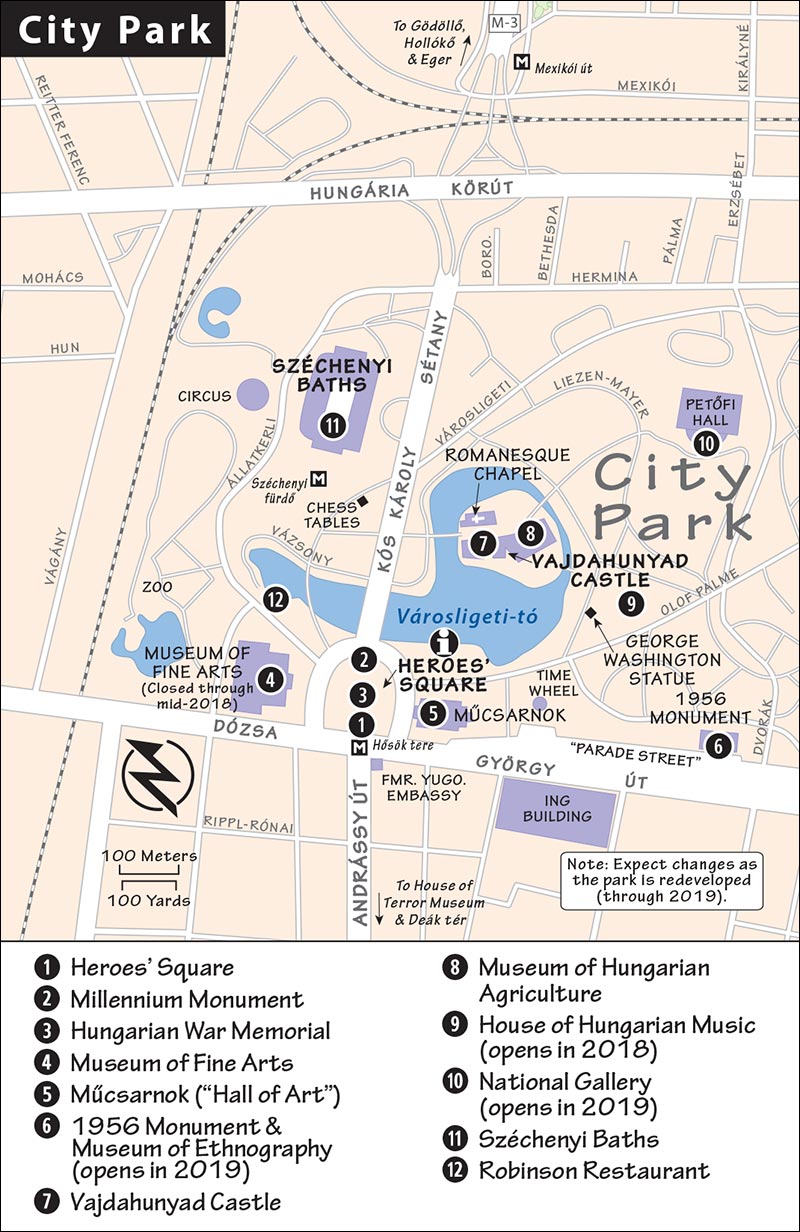

The early 21st century is also a boom time in Budapest. The city is busy creating an ambitious Museum Quarter in City Park. The park itself is being renovated, along with many of its buildings (such as the Museum of Fine Arts and Vajdahunyad Castle). They’re also erecting new, purpose-built homes for the National Gallery; Museum of Ethnography; Museum of Science, Technology, and Transport; and new House of Hungarian Music. Progress is ongoing, with the various buildings slated to open gradually over the course of 2018 and 2019. In the meantime, you’ll likely see construction underway. For details, see www.ligetbudapest.org.

Medical Help: Near Buda’s Széll Kálmán tér, FirstMed Centers is a private, pricey, English-speaking clinic (by appointment or urgent care, call first, Hattyú utca 14, 5th floor, district I, M2: Széll Kálmán tér, tel. 1/224-9090, www.firstmedcenters.com). Hospitals (kórház) are scattered around the city.

Pharmacies: The helpful BENU Gyógyszertár pharmacy is dead-center in Pest, between Vörösmarty and Széchenyi squares. Because they cater to clientele from nearby international hotels, they have a useful directory that lists the Hungarian equivalent of US prescription medicines (Mon-Fri 8:00-20:00, closed Sat-Sun, Dorottya utca 13, district V, M1: Vörösmarty tér, for location see map on here, tel. 1/317-2374). Each district has one 24-hour pharmacy (these should be noted outside the entrance to any pharmacy).

Monday Closures: Most of Budapest’s museums are closed on Mondays. But you can still take advantage of plenty of other sights and activities: all three major baths, Memento Park, Great Synagogue and Jewish Quarter, Matthias Church on Castle Hill, St. István’s Basilica, Parliament tour, Great Market Hall and Bálna Budapest, Opera House tour, City Park (and Zoo), Danube cruises, concerts, and bus, walking, and bike tours.

Train Tickets: Ticket-buying lines can be long at train stations, particularly for long-distance international trains. If you want to buy your ticket in advance, MÁV (Hungarian Railways) has a very convenient ticket office right in the heart of downtown Pest. They generally speak English and sell tickets for no additional fee (Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00, closed Sat-Sun, just up from the Chain Bridge and across from Erzsébet tér at József Attila utca 16, district V, M1: Vörösmarty tér, for location see map on here).

Post Offices: These are marked with a smart green posta logo (usually open Mon-Fri 8:00-18:00, Sat 8:00-12:00, closed Sun).

Laundry: Vajnóczki Tisztító Szalon, a block from the Oktogon, is a dry cleaner that also washes tourists’ laundry (1,000 Ft/kg, next-day service, Mon-Fri 8:00-18:00, Sat until 13:00, closed Sun, Szófia utca 8, for location see map on here, tel. 1/342-3796). Two cheap self-service launderettes are in the Seventh District nightlife zone: Laundry Budapest has lots of machines (daily 9:00-24:00, last wash at 22:00, Dohány utca 37, near M2: Blaha Lujza tér, tel. 1/781-0098, www.laundrybudapest.hu). Bazar Hostel has just a few (open daily 24 hours, free Wi-Fi, closer to the Great Synagogue, at Dohány utca 22).

English Bookstore: Bestsellers has a fine selection of new books, mostly in English; it’s near St. István’s Basilica (Mon-Fri 9:00-18:30, Sat 11:00-18:00, Sun 12:00-18:00, Október 6 utca 11—see map on here, tel. 1/312-1295).

Bike Rental: Budapest—with lots of traffic congestion—isn’t the easiest city for biking. But as the city adds more bike lanes and traffic-free zones, those comfortable with urban cycling may be tempted. You can rent a bike at Yellow Zebra (3,000 Ft/all day, 4,000 Ft/24 hours, see “Absolute Tour Center” listing on here).

Budapest also has a subsidized public bike network called Bubi (for “Budapest Bikes”). Bike stations are scattered throughout the Town Center and adjoining areas; you can pick a bike up at any station, and drop it off at any other—making this handy for one-way trips. First, you buy a “ticket” at http://molbubi.bkk.hu or at a docking station (500 Ft/24 hours, 1,000 Ft/72 hours, 2,000 Ft/week, plus a 25,000-Ft deposit on your credit card for the duration of the ticket). Once you have a ticket, it’s free to use a bike for 30 minutes or less, then costs 500 Ft for each additional 30 minutes. Ask at the TI if you need help figuring out the system.

Drivers: Friendly, English-speaking Gábor Balázs can drive you around the city or into the surrounding countryside (4,800 Ft/hour, 3-hour minimum in city, 4-hour minimum in countryside—good for a Danube Bend excursion, mobile +3620-936-4317, bgabor.e@gmail.com). Zsolt Gál is also available for transfers and side-trips, and specializes in helping people track down Jewish sites in the surrounding areas (mobile +3670-452-4900, forma111562@gmail.com). Note that these are drivers, not tour guides. For tour guides who can drive you to outlying sights, see “Tours in Budapest,” later.

Best Views: Budapest is a city of marvelous vistas. Some of the best are from the Citadella fortress (high on Gellért Hill), the promenade in front of the Royal Palace and the Fishermen’s Bastion on top of Castle Hill, and the embankments or many bridges spanning the Danube (especially the Chain Bridge). Don’t forget the view from the tour boats on the Danube—particularly lovely at night.

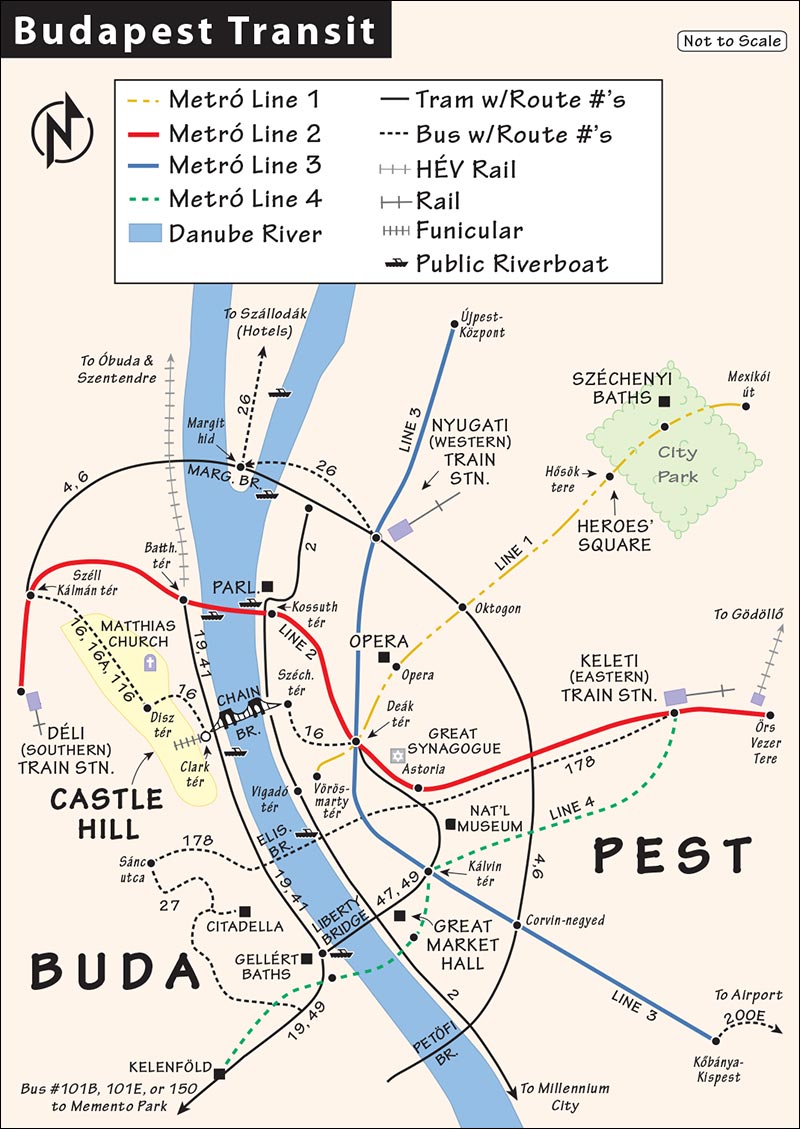

Budapest sprawls. Connecting your sightseeing just on foot is tedious and unnecessary. It’s crucial to get comfortable with the well-coordinated public transportation system: Metró lines, trams, buses, trolley buses, and boats. Budapest’s transit system website, www.bkk.hu, offers a useful route-planner and a downloadable app for on-the-go transit info.

Tickets: The same tickets work for the entire system. Buy them at kiosks, Metró ticket windows, or machines (with English instructions). As it can be frustrating to find a ticket machine (especially when you see your tram or bus approaching), I generally invest in a multiday ticket to have the freedom of hopping on at will.

Your options are as follows:

• Single ticket (vonaljegy, for a ride of up to an hour on any means of transit; transfers allowed only within the Metró system)—350 Ft (or 450 Ft if bought from the driver)

• Short single Metró ride (Metrószakaszjegy, 3 stops or fewer on the Metró)—300 Ft

• Transfer ticket (átszállójegy—allowing up to 90 minutes, including one transfer between Metró and bus)—530 Ft

• Pack of 10 single tickets (10 darabos gyűjtőjegy), which can be shared—3,000 Ft (that’s 300 Ft per ticket, saving you 50 Ft per ticket; note that these must stay together as a single pack—they can’t be sold separately)

• Unlimited multiday travel cards for Metró, bus, and tram, including a 24-hour travelcard (24 órás jegy, 1,650 Ft/24 hours), 72-hour travelcard (72 órás jegy, 4,150 Ft/72 hours), and seven-day travelcard (hetijegy, 4,950 Ft/7 days)

• 24-hour group travel card (csoportos 24 órás jegy, 3,300 Ft), covering up to five adults—a great deal for groups of three to five people

• The Budapest Card, which combines a multiday ticket with sightseeing discounts (see here)

Always validate single-ride tickets as you enter the bus, tram, or Metró station (stick it in the elbow-high box). On older buses and trams that have little red validation boxes, stick your ticket in the black slot, then pull the slot toward you to punch holes in your ticket. Multiday tickets need be validated only once. The stern-looking people with burgundy armbands waiting as you enter or exit the Metró want to see your validated ticket. Cheaters are fined 8,000 Ft on the spot, and you’ll be surprised how often you’re checked—they seem to be stationed at virtually every Metró escalator. All public transit runs from 4:30 in the morning until 23:50; a few designated night buses and trams operate overnight.

New Transit Cards: Budapest plans to phase out paper tickets in favor of electronic pay-as-you-go cards (similar to London’s Oyster card or New York’s Metrocard). When this happens, passengers will load up a plastic card with credit, then “touch in” and “touch out” as they enter and exit the system. This may be implemented as early as 2017 or 2018. Ask around, or see www.bkk.hu for the latest.

Handy Terms: Á ___ félé means “in the direction of ___.” Megálló means “stop” or “station,” and Végállomás means “end of the line.”

Riding Budapest’s efficient Metró, you really feel like you’re down in the guts of the city. There are four working lines:

• M1/yellow—The first subway line on the Continent, this line runs just 20 steps below street level under Andrássy út from the center to City Park. Dating from 1896, “the Underground” (Földalatti) is so shallow that you must follow the signs on the street (listing end points—ua Mexikói út felé takes you toward City Park) to gauge the right direction, because there’s no underpass for switching platforms. Though recently renovated, the M1 line retains its old-time atmosphere.

• M2/red—Built during the communist days, it’s 115 feet deep and designed to double as a bomb shelter. Going under the Danube to Buda, the M2 connects the Déli/Southern train station, Széll Kálmán tér (where you catch bus #16, #16A, or #116 to the top of Castle Hill), Batthyány tér (Víziváros and the HÉV suburban railway), Kossuth tér (behind the Parliament), Astoria (near the Great Synagogue on the Small Boulevard), and the Keleti/Eastern train station (where it crosses the M4/green line).

• M3/blue—This line makes a broad, boomerang-shaped swoop north to south on the Pest side. Its stations are noticeably older. Key stops include the Nyugati/Western train station, Ferenciek tere (in the heart of Pest’s Town Center), Kálvin tér (near the Great Market Hall and many recommended hotels; this is also where it crosses the M4/green line), and Corvin-negyed (near the Holocaust Memorial Center).

• M4/green—The newest line (opened in 2014) runs from southern Buda to the Gellért Baths, under the Danube to Fővám tér (behind the Great Market Hall) and Kálvin tér (where it crosses the M3/blue line), then up to Rákóczi tér (on the Grand Boulevard) and the Keleti/Eastern train station (where it crosses the M2/red line). Many of its stations boast boldly modern, waste-of-space concrete architecture that’s eye-opening to simply stroll through; the one at Gellért tér has a thermal spring-fed waterfall coursing past the main staircase.

The three original lines—M1, M2, and M3—cross only once: at the Deák tér stop (often signed as Deák Ferenc tér) in the heart of Pest, near where Andrássy út begins.

Aside from the historic M1 line, most Metró stations are at intersections of ring roads and other major thoroughfares. You’ll usually exit the Metró into a confusing underpass packed with kiosks, fast-food stands, and makeshift markets. Directional signs (listing which streets, addresses, and tram or bus stops are near each exit) help you find the right exit. Or do the prairie-dog routine: Surface to get your bearings, then head back underground to find the correct stairs up to your destination.

Metró platforms are usually very well-signposted, with a list of upcoming stops on the wall behind the tracks. Digital clocks either count down to the next train’s arrival, or count up from the previous train’s departure; either way, you’ll rarely wait more than a few minutes for the next train.

Budapest’s suburban rail system, or HÉV (pronounced “hayv,” stands for Helyiérdekű Vasút, literally “Railway of Local Interest”), branches off to the outskirts and beyond. On a short visit, it’s unlikely that you’ll need to use it, unless you’re heading to the Óbuda neighborhood (for its museums), the charming Danube Bend town of Szentendre, or the royal palace at Gödöllő.

The HÉV line that begins at Batthyány tér in Buda’s Víziváros neighborhood heads through Óbuda to Szentendre; from the station at Örs vezér tere, a different line runs east to Gödöllő. The HÉV is covered by standard transit tickets and passes for rides within the city of Budapest (such as to Óbuda). But if going beyond—such as to Szentendre or Gödöllő—you’ll have to pay more. Tell the ticket-seller (or punch into the machine) where you’re going, and you’ll be issued the proper ticket.

Budapest’s trams are handy and frequent, taking you virtually anywhere the Metró doesn’t. Here are some trams you might use (note that all of these run in both directions):

Tram #2: Follows Pest’s Danube embankment, parallel to Váci utca. From north to south, it begins at the Great Boulevard (Jászai Mari tér, near Margaret Bridge) and stops on either side of the Parliament (north side near the visitors center/Országház stop, as well as south side near the Kossuth tér Metró stop), Széchenyi István tér and the Chain Bridge, Vigadó tér, and the Great Market Hall (Fővám tér stop).

Trams #19 and #41: Run along Buda’s Danube embankment from Batthyány tér (with an M2/red Metró station, and HÉV trains to Óbuda and Szentendre). From Batthyány tér, these trams run (north to south) through Víziváros, with several helpful stops: Clark Ádám tér (the bottom of the Castle Hill funicular, near the stop for bus #16 up to Castle Hill), Várkert Bazár (Castle Park with escalators and elevators up to the Royal Palace); Rudas Gyógyfürdő (Rudas Baths); then around the base of Gellért Hill to Szent Gellért tér (Gellért Baths and M4/green Metró station).

Trams #4 and #6: Zip around Pest’s Great Boulevard ring road (Nagykörút), connecting Nyugati/Western train station and the Oktogon with the southern tip of Margaret Island and Buda’s Széll Kálmán tér (with M2/red Metró station). At night, this route is replaced by bus #6.

Trams #47 and #49: Connect the Gellért Baths in Buda with Pest’s Small Boulevard ring road (Kiskörút), with stops at the Great Market Hall (Fővám tér stop), the National Museum (Kálvin tér stop), the Great Synagogue (Astoria stop), and Deák tér (end of the line).

I use the Metró and trams for most of my Budapest commuting. But some buses are useful for shortcuts within the city, or for reaching outlying sights. Note that the transit company draws a distinction between gas-powered “buses” and electric “trolley buses” (which are powered by overhead cables). Unless otherwise noted, you can assume the following are standard buses:

Buses #16, #16A, and #116: All head up to the top of Castle Hill (get off at Dísz tér, in the middle of the hill—the closest stop to the Royal Palace). You can catch any of these three at Széll Kálmán tér (M2/red Metró line). When coming from the other direction, bus #16 makes several handy stops in Pest (Deák tér, Széchenyi István tér), then crosses the Chain Bridge for more stops in Buda (including Clark Ádám tér, at Buda end of Chain Bridge on its way up to the castle).

Trolley buses #70 and #78: Zip from near the Opera House (intersection of Andrássy út and Nagymező utca) to the Parliament (Kossuth tér).

Bus #178: Goes from Keleti/Eastern train station to central Pest (Astoria and Ferenciek tere Metró stops), then over the Elisabeth Bridge to Buda.

Bus #26: Begins at Nyugati/Western train station and heads around the Great Boulevard to Margaret Island, making several stops along the island.

Bus #27: Runs from either side of Gellért Hill to just below the Citadella fortress at the hill’s peak (Búsuló Juhász stop).

Bus #200E: Connects Liszt Ferenc Airport to the Kőbánya-Kispest M3/blue Metró station.

Buses #101B, #101E, and #150: Run from Kelenföld (the end of the line for the M4/green Metró line) to Memento Park.

Budapest’s public transit authority operates a system of Danube riverboats (hajójárat, marked with a stylish D logo) that connect strategic locations throughout the city. The riverboat system has drawbacks: Frequency is sparse (1-2/hour on weekdays, hourly on weekends; off-season weekdays only, hourly), and it’s typically slower than hopping on the Metró or a tram. But it’s also a romantic, cheap alternative to pricey riverboat cruises, and can be a handy way to connect some sightseeing points.

A 750-Ft ticket covers any trip; on weekdays, it’s also covered by a 24-hour, 72-hour, or seven-day travelcards (but not by the Budapest Card; on weekends, you have to buy a ticket regardless of your pass).

Lines #D11 and #D12 (on weekdays) and #D13 (on weekends) run in both directions through the city, including these stops within downtown Budapest:

• Népfürdő utca (Árpád híd), at the northern end of Margaret Island (the weekend boat also makes several additional stops on the island);

• Jászai Mari tér, at the Pest end of Margaret Bridge;

• Batthyány tér, on the Buda embankment in Víziváros;

• Kossuth Lajos tér, near the Parliament on the Pest side;

• Várkert Bazár, at the base of the grand entrance staircase to Buda Castle;

• Petőfi tér, on the Pest embankment next to the Legenda Cruises riverboats (dock 8); and

• Szent Gellért tér, at the Buda end of Liberty Bridge, next to the Gellért Baths.

Some stops may be closed if the river level gets very low.

Budapest’s public transportation is good enough that you probably won’t need to take many taxis. But if you do, you may run into a dishonest driver. Arm yourself with knowledge: Budapest strictly regulates its official taxis, which must be painted yellow and have yellow license plates. These taxis are required to charge identical rates, regardless of company: a drop rate of 450 Ft, and then 280 Ft/kilometer, plus 70 Ft/minute for wait time. A 10 percent tip is expected. A typical ride within central Budapest shouldn’t run more than 2,000 Ft. Despite what some slimy cabbies may tell you, there’s no legitimate extra charge for crossing the river, and prices are per ride—not per passenger.

Instead of hailing a taxi on the street, do as the locals do and call a cab from a reputable company—it’s cheaper and you’re more likely to get an honest driver. Try City Taxi (tel. 1/211-1111), Taxi 6x6 (tel. 1/266-6666), or Főtaxi (tel. 1/222-2222). Most dispatchers speak English, but if you’re uncomfortable calling, you can ask your hotel or restaurant to call for you.

Many “cabs” you’d hail on the streets are there only to prey on rich, green tourists. Avoid unmarked taxis (nicknamed “hyenas” by locals)—especially those waiting at tourist spots and train stations. If you do wave down a cab on the street, be sure it has a yellow license plate; otherwise, it’s not official. Ask for a rough estimate before you get in—if it doesn’t sound reasonable, walk away. If you wind up being dramatically overcharged for a ride, simply pay what you think is fair and go inside. If the driver follows you (unlikely), your hotel receptionist will defend you.

Budapest has an abundance of enthusiastic, hardworking young guides who speak perfect English and enjoy showing off their city. Given the reasonable fees and efficient use of your time, hiring your own personal expert is an excellent value. While they might be available last-minute, it’s better to reserve in advance by email.

I have three favorites, any of whom can do half-day or full-day tours, and can also drive you into the countryside: Péter Pölczman is an exceptional guide who really puts you in touch with the Budapest you came to see (€110/half-day, €190/full day, mobile +3620-926-0557, www.budapestyourself.com, polczman@freestart.hu or peter@budapestyourself.com). Andrea Makkay has professional polish and a smart understanding of what visitors really want to experience (€110/half-day, €190/full day, mobile +3620-962-9363, www.privateguidebudapest.com, andrea.makkay@gmail.com—arrange details by email; if Andrea is busy, she can arrange to send you with another guide). And George Farkas is particularly well-attuned to the stylish side of this fast-changing metropolis (€120/half-day, €220/full day, mobile +3670-335-8030, www.mybudapesttours.hu, georgefarkas@gmail.hu).

Elemér Boreczky, a semiretired university professor, leads walking tours with a soft-spoken, scholarly approach, emphasizing Budapest’s rich tapestry of architecture as “frozen music.” Elemér is ideal if you want a walking graduate-level seminar about the easy-to-miss nuances of this grand city (€25/hour, mobile +3630-491-1389, www.culturaltours.mlap.hu, boreczky.elemer@gmail.com).

Péter, Andrea, George, and Elemér have all been indispensable help to me in writing and updating this book.

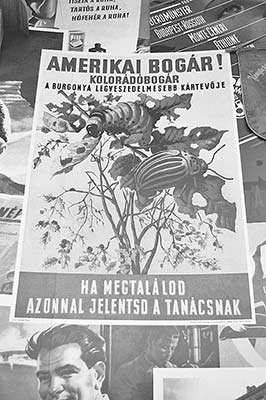

Budapest’s best-established walking-tour company is Absolute Tours, run by Oregonian Ben Frieday. Travelers with this book get a discount on any tour (15 percent if you book online—enter coupon code “RICK”—or 10 percent for tours booked in person). Their options include the 3.5-hour Absolute Walk, offering a good overview of Budapest; the Hammer & Sickle Tour, with a mini museum of communist artifacts and sites related to the 1956 Uprising; the Hungro Gastro Food and Wine Tasting, which includes a tour and tastings at the Great Market Hall and nearby specialty shops; the Night Stroll, which includes a one-hour cruise on the Danube; as well as nightlife tours, a Christmas Market tour (Dec only), and an “Alternative Budapest” tour that visits artsy, edgy, off-the-beaten-path parts of town. For prices and schedules, see www.absolutetours.com or contact the office (tel. 1/269-3843, mobile +3620-929-7506). Most tours depart from the Absolute Tour Center behind the Opera House (see the “Absolute Tour Center” listing on here); however, the food-and-wine tour meets at the Great Market Hall, and the “Alternative” tour departs from the blocky, green-domed Lutheran church at Deák tér, near the Metró station.

You’ll also see various companies advertising “free” walking tours. While there is no set fee to take these tours, guides are paid only if you tip (they’re hoping for 2,000 Ft/person). They offer a basic 2.5-hour introduction to the city, as well as itineraries focusing on the communist era and the Jewish Quarter. Because they’re working for tips, the guides are highly motivated to impress their customers. But because the “free” tag attracts very large groups, these tours tend to be less intimate than paid tours, and (especially the introductory tours) take a once-over-lightly “infotainment” approach. As this scene is continually evolving, look for local fliers to learn about the options and meeting points.

Cruising the Danube, while touristy, is a fun and convenient way to get a feel for the city’s grand layout. The most established company, Legenda Cruises, is a class act that runs well-maintained, glassed-in panoramic boats day and night. All of their cruises include a free drink and romantic headphone commentary. By night, TV monitors show the interiors of the great buildings as you float by.

I’ve negotiated a special discount with Legenda for my readers—but you must book directly and ask for the Rick Steves price. By day, the one-hour “Duna Bella” cruise costs 3,120 Ft for Rick Steves readers; if you want, you can hop off at Margaret Island to explore on your own, then return after 1.5 hours on a later cruise (6/day April-Sept, 4/day March and Oct, 1/day Nov-Feb—but no Margaret Island stop in winter). By night, the one-hour “Danube Legend” cruise (with no Margaret Island visit) costs 4,400 Ft for Rick Steves readers (4/day March-Oct, 1/day Nov-Feb). On weekends, it’s smart to call ahead and reserve a spot for the evening cruises. Note: These special prices are for 2017, and may be slightly higher in 2018.

The Legenda dock is in front of the Marriott on the Pest embankment (find pedestrian access under tram tracks at downriver end of Vigadó tér, district V, M1: Vörösmarty tér, tel. 1/317-2203, www.legenda.hu). Competing river-cruise companies are nearby, but given the discount, Legenda offers the best value.

The best option for tours by bike and Segway (a stand-up electric scooter) is Yellow Zebra, a sister company of Absolute Tours (bike tours—8,500 Ft, 3.5 hours, no tours Dec-Feb or in freezing temperatures; Segway tours—19,500 Ft, 2.5 hours, begins with 30-minute training). My readers get a 15 percent discount when booking online (www.yellowzebratours.com, enter coupon code “RICK”), or 10 percent off if booking in person. These tours meet at the Absolute Tour Center behind the Opera House (see here).

Various companies run hop-on, hop-off bus tours, which make 12 to 16 stops as they cruise around town on a two-hour loop with headphone commentary (generally 5,000/24 hours, 6,000 Ft/48 hours). Most companies also offer a wide variety of other tours, including dinner boat cruises and trips to the Danube Bend. Pick up fliers about all these tours at the TI or in your hotel lobby.

This company offers a bus tour with a twist: Its amphibious bus can actually float on the Danube River, effectively making this a combination bus-and-boat tour. The live guide imparts dry English commentary as you roll (and float). While it’s a fun gimmick, the entry ramp into the river (facing the north end of Margaret Island) is far from the most scenic stretch, and the river portion is slow-paced—showing you the same Margaret Island scenery twice, plus a circle in front of the Parliament. The Legenda Cruises boat tours, described earlier, give you more scenic bang for your buck (8,500 Ft, 2 hours, 4/day April-Oct, 3/day Nov-March, departs from Széchenyi tér near Gresham Palace, tel. 1/332-2555, www.riverride.com).

Andy Steves (Rick’s son) runs Weekend Student Adventures (WSA Europe), offering 3-day and 10-day budget travel packages across Europe including accommodations, skip-the-line sightseeing, and unique local experiences. Locally guided and DIY unguided options are available for student and budget travelers in 12 of Europe’s most popular cities, including Budapest (guided trips from €199, see www.wsaeurope.com for details).

▲▲Hungarian Parliament (Országház)

Szabadság Tér (Liberty Square)

▲St. István’s Basilica (Szent István Bazilika)

▲Chain Bridge (Széchenyi Lánchíd)

▲Margaret Island (Margitsziget)

▲▲Great Market Hall (Nagyvásárcsarnok)

ALONG THE SMALL BOULEVARD (KISKÖRÚT)

▲Hungarian National Museum (Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum)

▲▲Great Synagogue (Nagy Zsinagóga)

▲▲Hungarian State Opera House (Magyar Állami Operaház)

Franz Liszt Square (Liszt Ferenc Tér)

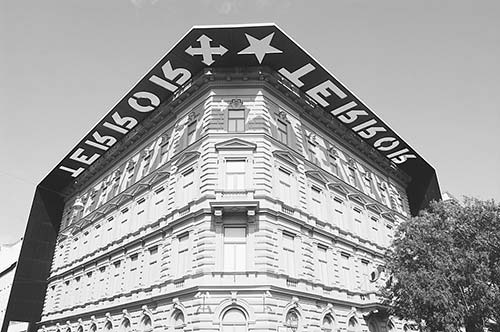

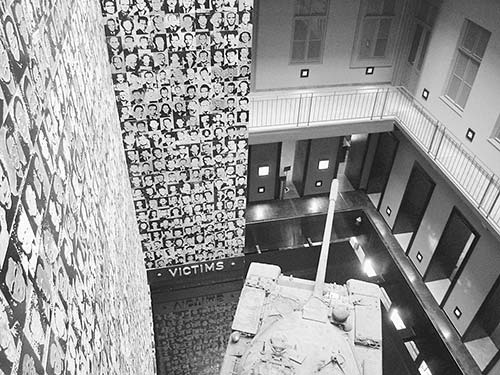

▲▲House of Terror (Terror Háza)

▲▲Vajdahunyad Castle (Vajdahunyad Vára)

▲▲▲Széchenyi Baths (Széchenyi Fürdő)

▲▲Holocaust Memorial Center (Holokauszt Emlékközpont)

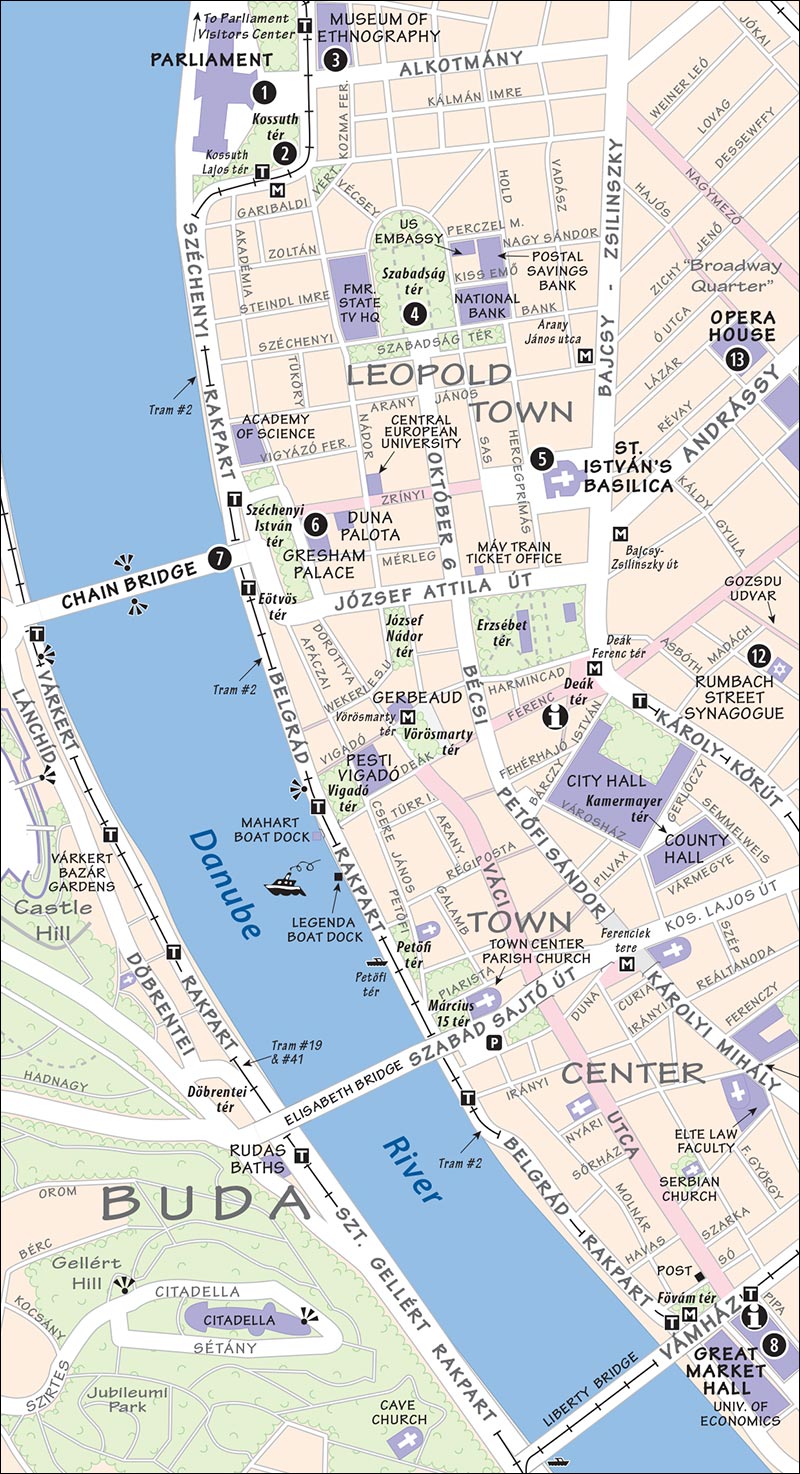

Most of Pest’s top sights cluster in five neighborhoods: Leopold Town and the Town Center (together forming the city’s “downtown”); the Jewish Quarter, just outside the inner ring road; along the grand boulevard Andrássy út; and at that boulevard’s end, near Heroes’ Square and City Park.

Several other excellent sights are not contained in these areas, and are covered in greater depth in this chapter: along the Small Boulevard (Kiskörút); along the Great Boulevard (Nagykörút); and along the boulevard called Üllői út.

The Parliament building, which dominates Pest’s skyline, is the centerpiece of the city’s banking and business district. Called Lipótváros (“Leopold Town”), this snazzy “uptown” quarter features some of the best of Budapest’s many monuments. Below, I’ve linked up the top sights in Leopold Town as a self-guided walk, starting at the grandiose Parliament building and ending at the Chain Bridge.

With an impressive facade and an even more extravagant interior, the oversized Hungarian Parliament dominates the Danube riverbank. A hulking Neo-Gothic base topped by a soaring Neo-Renaissance dome, it’s one of the city’s top landmarks. Touring the building offers the chance to stroll through one of Budapest’s best interiors. While the guides can be hit-or-miss, the dazzling building speaks for itself.

Cost and Hours: 5,400 Ft, half-price for EU citizens if you show your passport. English tours are usually daily at 10:00, 12:00, 13:00, 14:00, and 15:00—but there are often more tours with demand (especially at 8:30 and/or 9:45), or fewer for no apparent reason, so it’s smart to reserve in advance. On Mondays when parliament is in session (generally Sept-May), there are no tours after 10:00.

Getting There: Ride tram #2 to the Országház stop, which is next to the visitors center entrance (Kossuth tér 1, district V). You can also ride the M2/red Metró line to Kossuth tér, then walk to the other end of the Parliament building to find the visitors center.

Getting Tickets: Tickets come with an appointed tour time and often sell out. To ensure getting a space, it’s worth paying an extra 220 Ft per ticket to book online a day or two in advance at www.jegymester.hu. Select “Parliament Visit,” then a date and time of an English tour, and be sure to specify “full price” (unless you have an EU passport). You’ll have to create an account, but it’s typically no problem to use a US address, telephone number, and credit card. Print out your eticket and show up at the Parliament visitors center at the appointed time (if you can’t print it, show up early enough to have them print it out for you at the ticket desk—which can have long lines, especially in the morning).

If you didn’t prebook a ticket, go to the visitors center—a modern, underground space at the northern end of the long Parliament building (look for the statue of a lion on a pillar)—and ask what the next available tour time is. The 10:00 English tour is almost always sold out online, but there may be space on an earlier tour (early risers should show up at 8:00 to try their luck). Afternoon tours are the most likely to have space. The visitors center and ticket desk are open daily 8:00-18:00 (sometimes closes earlier Mon), and only sell tickets for the same day—if booking in advance, you must use the ticket website.

Information: Tel. 1/441-4904, www.parlament.hu.

Background: The Parliament was built from 1885 to 1902 to celebrate the Hungarian millennium year of 1896 (see sidebar on here). Its elegant, frilly spires and riverside location were inspired by its counterpart in London (where the architect studied). When completed, the Parliament was a striking and cutting-edge example of the mix-and-match Historicist style of the day. Like the Hungarian people, this building is at once grandly ambitious and a somewhat motley hodgepodge of various influences—a Neo-Gothic palace topped with a Neo-Renaissance dome, which once had a huge, red communist star on top of the tallest spire. Fittingly, it’s the city’s top icon. The best views of the Parliament are from across the Danube—especially in the late-afternoon sunlight.

Visiting the Parliament: The visitors center has WCs, a café, a gift shop, and the Museum of the History of the Hungarian National Assembly. Once you have your ticket in hand, be at the airport-type security checkpoint inside the visitors center at least five minutes before your tour departure time.

On the 45-minute tour, your guide will explain the history and symbolism of the building’s intricate decorations and offer a lesson in the Hungarian parliamentary system. You’ll see dozens of bushy-mustachioed statues illustrating the occupations of workaday Hungarians through history, and find out why a really good speech was nicknamed a “Havana” by cigar-aficionado parliamentarians.

To begin the tour, you’ll climb a 133-step staircase (with an elevator for those who need it) to see the building’s monumental entryway and 96-step grand staircase—slathered in gold foil and frescoes, and bathed in shimmering stained-glass light. Then you’ll gape up under the ornate gilded dome for a peek at the heavily guarded Hungarian crown, which is overlooked by statues of 16 great Hungarian monarchs, from St. István to Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa. Finally, you’ll walk through a cushy lounge—across one of Europe’s largest carpets—to see the legislative chamber.

• The vast square behind the Parliament is studded with attractions. Stay where you are for a quick...

This square is sprinkled with interesting monuments and packed with Hungarian history. But it’s gone through a lot of changes in the last few years, at the hands of architects and urban planners working under the steady guidance of the ruling Fidesz party, led by Viktor Orbán. A highly nationalistic, right-wing party, which swept to power after Hungarians grew weary of the bumblings of the poorly organized, shortsighted left-wing opposition party, Fidesz has exerted its influence over every walk of Hungarian life...beginning with the look of this building and square, and the monuments around it. The square itself used to be a more higgledy-piggledy mix of ragged asphalt, parks, monuments, and trees. But Fidesz wanted the mighty Parliament building to stand bold and unobstructed. Several older monuments (including, ironically, an “eternal” flame honoring victims of the communists) were swept away. Trees were cut down overnight, before would-be protesters could make a peep. And today the square has a scrubbed-clean look that some critics consider almost fascist.

Look to the right end of the Parliament. Poking up is a pillar topped by a lion being strangled and bitten by a giant snake (a typically heavy-handed Fidesz monument). This pillar marks the entrance to the Parliament visitors center; if you want to check on the availability of tours today, now’s a good time (see details earlier).

Looking a bit farther to the right, at the end of the park you’ll see another stony tribute, this one to the square’s namesake, Lajos Kossuth, who led the 1848 Revolution against the Habsburgs. The street that leaves this square behind Kossuth’s left shoulder is Falk Miksa utca, Budapest’s “antique row”—a great place to browse for nostalgic souvenirs.

Panning right from the Kossuth statue, across the tram tracks you’ll see the stately home of the Museum of Ethnography. While its collection of Hungarian folk artifacts is good (closed Mon), the building itself is also notable. The design was the first runner-up for the Parliament building, so they built it here, where it originally housed the Supreme Court. In a few years, the museum collection will move out to City Park, with plans for the Supreme Court to move back into its original home.

To the right, the Ministry of Agriculture was the second runner-up for the Parliament. Today it features a very low-profile, but poignant, monument to the victims of the 1956 Uprising against Soviet rule (see the “1956” sidebar): At the right end of the protruding arcade, notice that the walls are pockmarked with little metal dollops (you may have to walk closer to see these clearly). Two days into the uprising, on October 25, the ÁVH (communist police) and Soviet troops on the rooftop above opened fire on demonstrators gathered in this square—massacring many and leaving no doubt that Moscow would not tolerate dissent. In the monument, each of the little metal knobs represents a bullet.

Spin farther to the right, where a dramatic equestrian statue of Ferenc Rákóczi stands in the park. Rákóczi valiantly—but unsuccessfully—led the Hungarians in their War of Independence (1703-1711) against the Habsburgs. Although they lived more than a century apart, Rákóczi and Kossuth—who now face each other across this square—were aligned in their rebellion against the Habsburgs.

Complete your 360 and face the Parliament again. Every so often, costumed soldiers appear on the front steps for a brief “changing of the guard” ceremony set to recorded music...another very new, very patriotic custom, compliments of Fidesz.

In the wide sidewalk that runs in front of the Parliament, near the beautifully landscaped gardens, you’ll see staircases leading to modest, hidden, subterranean museums (both free and open daily 10:00-18:00). These offer a cool break from the crowds and a glimpse into the heating and cooling tunnels beneath Kossuth tér. The (skippable) one on the right is the lapidarium (kőtár), displaying old stone decorations from the Parliament—including gargoyle-like adornments from the spires.

More interesting (and on our way to the next stop) is the one on the left, marked 1956. Heading down these stairs, you’ll find a poignant memorial to the 1956 Uprising that began on this very square (see sidebar). You’ll see photos of the events, and video interviews of eyewitnesses to the massacre on this square on October 25, 1956 (as well as other government mass shootings around Hungary that fall). At the end of the hall is a memorial grave to the victims, and the symbol of the uprising: a tattered Hungarian flag with a hole cut out of the center.

Budapest is a city of great monuments, and some of the most vivid are on or near this square.

• Circle around the left side of the giant Parliament building, passing another statue on a pillar, and walk all the way to the bannister overlooking a spectacular view of Buda. Walk along the banister to the left until you come upon a statue of a young man, lost deep in thought, gazing into the Danube.

Attila József (1905-1937): This beloved modern poet lived a tumultuous, productive, and short life before he killed himself by jumping in front of a train at age 32. József’s poems of life, love, and death—mostly written in the 1920s and 1930s—are considered the high point of Hungarian literature. His birthday (April 11) is celebrated as National Hungarian Poetry Day.

Here József re-enacts a scene from one of his best poems, “At the Danube.” It’s a hot day—his jacket lies in a heap next to him, his shirtsleeves are rolled up, and he cradles his hat loosely in his left hand. “As I sat on the bank of the Danube, I watched a watermelon float by,” he begins. “As if flowing out of my heart, murky, wise, and great was the Danube.” In the poem, József uses the Danube as a metaphor for life—for the way it has interconnected cities and also times—as he reflects that his ancestors likely pondered the Danube from this same spot. Looking into his profound eyes, you sense the depth of this artist’s tortured inner life.

• Walk down the steps next to József, and stand at the railing just above the busy road. If you visually trace the Pest riverbank to the left about 100 yards, just before the tree-filled, riverfront park, you can just barely see several low-profile dots lining the embankment. This is a...

Holocaust Monument: Consisting of 50 pairs of bronze shoes, this monument commemorates the Jews who were killed when the Nazis’ puppet government, the Arrow Cross, came to power in Hungary in 1944. While many Jews were sent to concentration camps, the Arrow Cross massacred some of them right here, shooting them and letting their bodies fall into the Danube.

• If you’d like a closer look at the shoes, use the crosswalk (50 yards to your right) to cross the busy embankment road and follow the waterline.

When you’re ready to move on, turn your back to the Danube and walk inland, along the ugly building (with an entrance to the Metró), up to the back corner of Kossuth tér. Cross the street in a little park (at Vértanúk tere), where you’ll see a monument to...

Imre Nagy (1896-1958): The Hungarian politician Imre Nagy (EEM-ray nodge), now thought of as an anticommunist hero, was actually a lifelong communist. In the 1930s, he allegedly worked for the Soviet secret police. When the 1956 Uprising broke out on October 23, Imre Nagy was drafted (reluctantly, some say) to become the head of the movement to soften the severity of the communist regime. Because he was an insider, it briefly seemed that Nagy might hold the key to finding a middle path (represented by the bridge he’s standing on) between the suffocating totalitarian model of Moscow and the freedom of the West. But the optimism was short-lived. The Soviets violently put down the uprising, arrested and sham-tried Nagy, executed him, and buried him disgracefully, face-down in an unmarked grave. The regime forced Hungary to forget about Nagy. Later, when communism was in its death throes in 1989, the Hungarian people rediscovered Nagy as a hero. His body was located, exhumed, and given a ceremonial funeral at Heroes’ Square. And today, thanks to this monument, Nagy keeps a watchful eye on today’s lawmakers in the Parliament across the way.

• Go up the short, diagonal street beyond Nagy, called Vécsey utca. After just one block, you emerge into...

One of Budapest’s most genteel squares, this space is marked by a controversial monument to the Soviet soldiers who liberated Hungary at the end of World War II, and ringed by both fancy old apartment blocks and important buildings (such as the former Hungarian State Television headquarters, the US Embassy, and the National Bank of Hungary). A fine café, fun-filled playgrounds, statues of prominent Americans (Ronald Reagan and Harry Hill Bandholtz), and yet another provocative monument (to the Hungarian victims of the Nazis) round out the square’s landmarks. Take a moment to tune into two of the more recent (and more divisive) monuments on the square.

• The first person you’ll see as you enter the square, striding confidently away from the Parliament, is an actor-turned-politician you may recognize...

Ronald Reagan: When Fidesz took power in 2010, they quickly began rolling back previous democratic reforms and imposing alarming constraints on the media. Many international observers—including the US government—spoke out against what they considered an infringement on freedom of the press. In an effort to appease American concerns, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán erected this statue on one of his capital’s main squares—and then, perhaps not quite grasping the subtleties of American politics, invited Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to the unveiling. It’s fun to watch the steady stream of passersby (both Hungarians and tourists) do a double-take, chuckle, then snap a photo with The Gipper.

• Now enjoy a slow stroll to the opposite end of the square, where you’ll find the...

Monument to the Hungarian Victims of the Nazis: This recent addition to the square—another heavy-handed Fidesz production—commemorates the German invasion of Hungary on March 19, 1944. Standing in the middle of a broken colonnade, an immaculate angel holds a sphere with a double cross (part of the crown jewels and a symbol of Hungarian sovereignty). Overhead, a mechanical-looking black eagle (symbolizing Germany) screeches in, its talons poised to strike.

Although offensive enough for its lack of artistry, this monument was instantly controversial for the way it whitewashes Hungarian history. Viewing this, you might imagine that Hungary was a peaceful land that was unwittingly caught up in the Nazi war machine. In fact, the Hungarian government was an ally of Nazi Germany for more than three years before this invasion. And there’s no question that, after the invasion, many Hungarians enthusiastically collaborated with their new Nazi overlords.

Mindful of the old adage about people who forget their own history, locals have created a makeshift counter-memorial to the victims of the World War II-era Hungarians (not just Germans) in front of this official monument.

On a lighter note, the fountain that faces the monument is particularly entertaining. Sensors can tell when you’re about to walk through the wall of water...and the curtain of water automatically parts just long enough for you to pass. Try it.

• From the monument, continue two blocks straight ahead, up Hercegprimás utca. You’ll emerge into a broad plaza in front of...

Budapest’s biggest church is one of its top landmarks. The grand interior celebrates St. István, Hungary’s first Christian king. You can see his withered, blackened, millennium-old fist in a gilded reliquary in the side chapel. Or you can zip up on an elevator (or climb up stairs partway) to a panorama terrace with views over the rooftops of Pest. The skippable treasury has ecclesiastical items, historical exhibits, and artwork (reached by elevator, to the right as you face the church). The church also hosts regular organ concerts (advertised near the entry).

Cost and Hours: Interior—free but 200-Ft donation strongly suggested, open to tourists Mon 9:00-16:30, Tue-Fri 9:00-17:00, Sat 9:00-13:00, Sun 13:00-17:00, open slightly later for worshippers; panorama terrace—500 Ft, daily June-Sept 10:00-18:30, March-May and Oct 10:00-17:30, Nov-Feb 10:00-16:30; treasury-400 Ft, same hours as terrace; music concerts Mon, Tue, and Thu—see here; Szent István tér, district V, M1: Bajcsy-Zsilinszky út or M3: Arany János utca.

Visiting the Church: The church is only about 100 years old—like most Budapest landmarks, it was built around the millennial celebrations of 1896. Head up the grand stairs to get oriented. To the right is the ticket desk, the elevator to the treasury, and the entrance to the church. To the left is the elevator to the panoramic tower.

The church’s interior is dimly lit but gorgeously restored; all the gilded decorations glitter in the low light. You’ll see not Jesus, but St. István (Stephen), Hungary’s first Christian king, glowing above the high altar.

The church’s main claim to fame is the “holy right hand” of St. István. The sacred fist—a somewhat grotesque, 1,000-year-old withered stump—is in a jeweled box in the chapel to the left of the main altar (follow signs for Szent Jobb Kápolna, chapel often closed). Pop in a 200-Ft coin for two minutes of light. Posted information describes the hand’s unlikely journey to this spot (chapel open slightly shorter hours than church—look for signs).

On your way out, in the exit foyer, you’ll find a small exhibit about the building’s history.

• From here, you’re very close to the boulevard called Andrássy út, which leads to the Opera House, House of Terror, and City Park (all described starting on here). To get there, walk around the right side of the basilica, and turn right on busy Bajcsy-Zsilinszky út; Andrássy út begins across the street, on your left.

But for now, we’ll head to the Danube for a good look at the mighty Chain Bridge. Walk straight ahead from St. István’s main staircase down Zrínyi Utca. This recently pedestrianized people zone passes (on the right) Central European University, a graduate school largely funded by Hungarian-American George Soros, and its good bookshop. Later, after crossing Nádor utca, on the left you’ll see Duna Palota, a venue and ticket office for Hungária Koncert’s popular tourist shows (described on here).

Zrínyi utca dead-ends at the big traffic circle called Roosevelt tér. Turn left and walk a half-block to the entrance (on the left) of the...

This was Budapest’s first building in the popular Historicist style, and also incorporates elements of Art Nouveau. Budapest boomed in an era when architectural eclecticism—mashing together bits and pieces of different styles—was in vogue. But because much of the city’s construction was compressed into a short window of time, even these disparate styles enjoy an unusual harmony. Damaged in World War II, the building was an eyesore for decades. (Reportedly, an aging local actress refused to move out, so developers had to wait for her to, ahem, vacate before they could reclaim the building.) In 1999, the Gresham Palace was meticulously restored to its former glory and converted to a luxury hotel. Even if you can’t afford to stay here (see here), saunter into the lobby and absorb the gorgeous details (lobby open 24 hours daily, Széchenyi tér 5, district V, M1: Vörösmarty tér or M2: Kossuth tér).

• Grandly spanning the Danube from this spot is Budapest’s best bridge...

One of the world’s great bridges connects Pest’s Széchenyi tér and Buda’s Clark Ádám tér. This historic, iconic bridge, guarded by lions (symbolizing power), is Budapest’s most enjoyable and convenient bridge to cross on foot.

Until the mid-19th century, only pontoon barges spanned the Danube between Buda and Pest. In the winter, the pontoons had to be pulled in, leaving locals to rely on ferries (in good weather) or a frozen river. People often walked across the frozen Danube, only to get stuck on the other side during a thaw, with nothing to do but wait for another cold snap.

Count István Széchenyi was stranded for a week trying to get to his father’s funeral. After missing it, Széchenyi commissioned Budapest’s first permanent bridge—which was also a major symbolic step toward another of Széchenyi’s pet causes, the unification of Buda and Pest. The Chain Bridge was built by Scotsman Adam Clark between 1842 and 1849, and it immediately became an important symbol of Budapest. Széchenyi—a man of the Enlightenment—charged both commoners and nobles a toll for crossing his bridge, making it an emblem of equality in those tense times. Like all of the city’s bridges, the Chain Bridge was destroyed by the Nazis at the end of World War II, but was quickly rebuilt.

• As you look out to the Danube from here, to the right you can see the tip of...

In the Middle Ages, this island in the Danube (just north of the Parliament) was known as the “Isle of Hares.” In the 13th century, a desperate King Béla IV swore that if God were to deliver Hungary from the invading Tatars, he would dedicate his youngest daughter Margaret to the Church. When the Tatars left, Margaret was shipped to a nunnery here. Margaret embraced her new life as a castaway nun, and later refused her father’s efforts to force her into a politically expedient marriage with a Bohemian king. As a reward for her faith, she became St. Margaret of Hungary.

Today, while the island officially has no permanent residents, urbanites flock here to relax in a huge, leafy park in the midst of the busy city...yet so far away. No cars are allowed on the island—just public buses. The island rivals City Park as the best spot in town for strolling, jogging, biking (you can rent a bike at Bringóhintó, with branches at both ends of the island), and people-watching. Rounding out the island’s attractions are an iconic old water tower, the remains of Margaret’s convent, a rose garden, a game farm, and a “musical fountain” that performs to the strains of Hungarian folk tunes.

Getting There: Bus #26 begins at Nyugati/Western train station, crosses the Margaret Bridge, then drives up through the middle of the island—allowing visitors to easily get from one end to the other (3-6/hour). Trams #4 and #6, which circulate around the Great Boulevard, cross the Margaret Bridge and stop at the southern tip of the island, a short walk from some of the attractions. You can also reach the island by public riverboat—weekday boats reach the two ends of the island, and weekend ones make several stops along the way. It’s also a long but scenic walk between Margaret Island and other points in the city.

• If you’d like to head for the heart of Pest, Vörösmarty tér (and the sights listed next), it’s just two long blocks away: Turn left out of the Gresham Palace, and walk straight on Dorottya utca.

Pest’s Belváros (“Inner Town”) is its gritty urban heart—simultaneously its most beautiful and ugliest district. You’ll see fancy facades, some of Pest’s best views from the Danube embankment, richly decorated old coffeehouses that offer a whiff of the city’s Golden Age, and a cavernous, colorful market hall filled with Hungarian goodies. But you’ll also experience crowds, grime, and pungent smells like nowhere else in Budapest. Atmospherically shot through with the crumbling elegance of former greatness, Budapest is a place where creaky old buildings and sleek modern ones feel equally at home. Remember: This is a city in transition. Enjoy the rough edges while you can. They’re being sanded off at a remarkable pace—and soon, tourists like you will be nostalgic for the “authentic” old days.

Below, I’ve linked the main landmarks in the Town Center with a self-guided walk, starting at the square called Vörösmarty tér and ending at the Great Market Hall.

The central square of the Town Center, dominated by a giant statue of the revered Romantic poet Mihály Vörösmarty and the venerable Gerbeaud coffee shop, is the hub of Pest sightseeing.

At the north end of the square is the landmark Gerbeaud café and pastry shop. Between the World Wars, the well-to-do ladies of Budapest would meet here after shopping their way up Váci utca. Today it’s still the meeting point in Budapest...for tourists, at least. Consider stepping inside to appreciate the elegant old decor, or for a cup of coffee and a slice of cake (but meals here are overpriced). Better yet, hold off for now—even more appealing cafés are nearby (and listed under “Budapest’s Café Culture,” on here).

The yellow M1 Metró stop in front of Gerbeaud is the entrance to the shallow Földalatti, or “underground”—the first subway on the Continent (built for the Hungarian millennial celebration in 1896). Today, it still carries passengers to Andrássy út sights, running under that boulevard all the way to City Park.

Walk to the far end of the square, and look up the street that’s to your left. This traffic-free street (Deák utca)—also known as “Fashion Street,” with top-end shops—is the easiest and most pleasant way to walk to Deák tér and, beyond it, through Erzsébet tér to Andrássy út.

• Extending straight ahead from Vörösmarty tér is a broad, bustling, pedestrianized shopping street. Look—but do not walk—down...

Dating from 1810-1850, Váci utca (VAHT-see OOT-zah) is one of the oldest streets of Pest. Váci utca means “street to Vác”—a town 25 miles to the north. This has long been the street where the elite of Pest would go shopping, then strut their stuff for their neighbors on an evening promenade. Today, the tourists do the strutting here—and the Hungarians go to American-style shopping malls.

This boulevard—Budapest’s tourism artery—was a dreamland for Eastern Bloc residents back in the 1980s. It was here that they fantasized about what it might be like to be free, while drooling over Nikes, Adidas, and Big Macs before any of these “Western evils” were introduced elsewhere in the Warsaw Pact region. In fact, partway down the street (on the right, at Régi Posta utca) is the first McDonald’s behind the Iron Curtain, where people from all over the Eastern Bloc flocked to dine. Since you had to wait in a long line—stretching around the block—to get a burger, it wasn’t “fast food”...but at least it was “West food.”

Ironically, this street—once prized by Hungarians and other Eastern Europeans because it felt so Western—is what many Western tourists today mistakenly think is the “real Budapest.” Visitors mesmerized by this people-friendly stretch of souvenir stands, tourist-gouging eateries, and upscale boutiques are likely to miss some more interesting and authentic areas just a block or two away. Don’t fall for this trap. You can have a fun and fulfilling trip to this city without ever setting foot on Váci utca.

• For a more appealing people zone than Váci utca, detour from Vörösmarty tér a block toward the river, to the inviting...

Some of the best views in Budapest are from this walkway facing Castle Hill—especially this stretch, between the white Elisabeth Bridge (left) and the iconic Chain Bridge (right). This is a favorite place to promenade (korzó), strolling aimlessly and greeting friends.