Wien

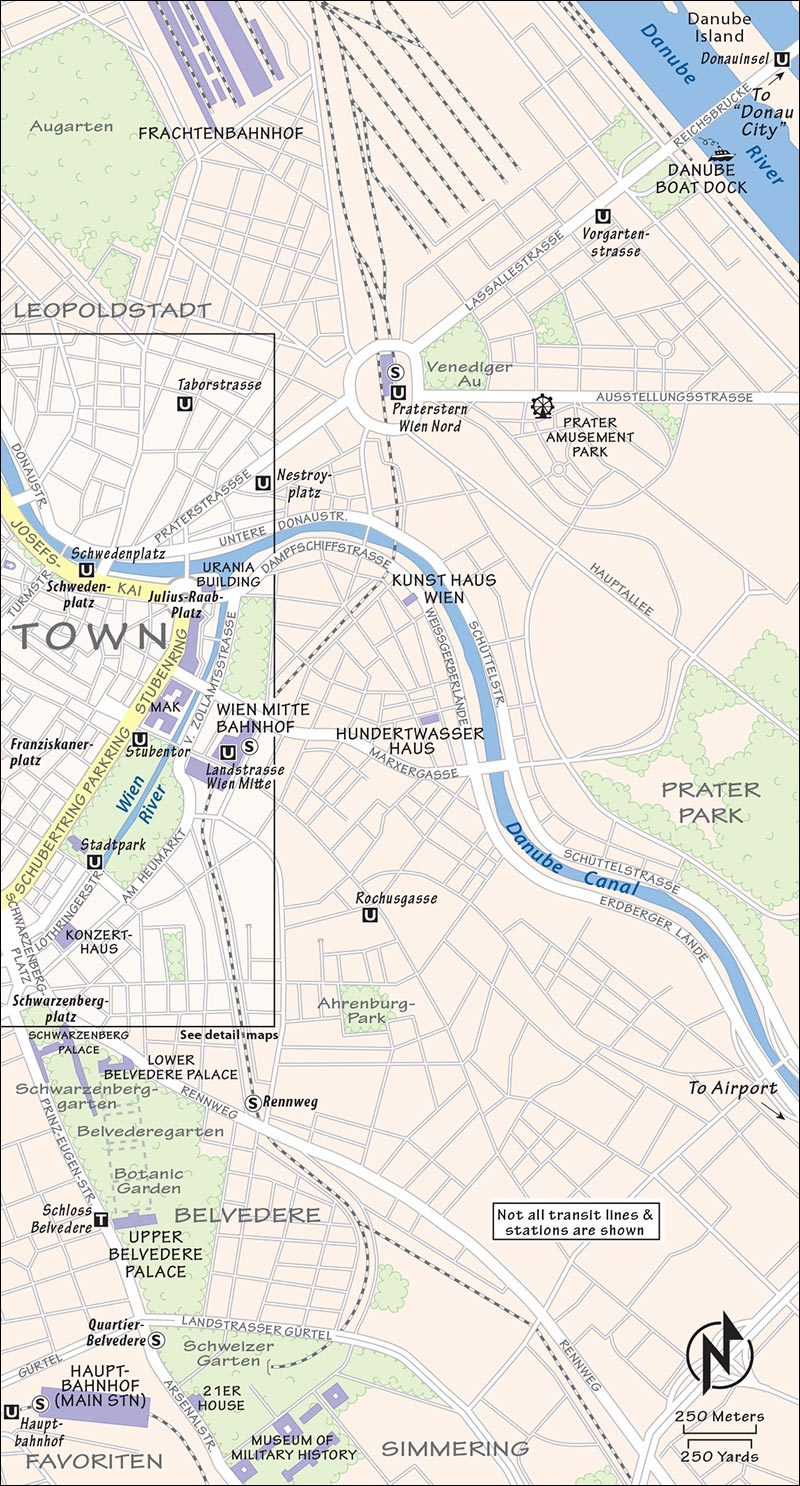

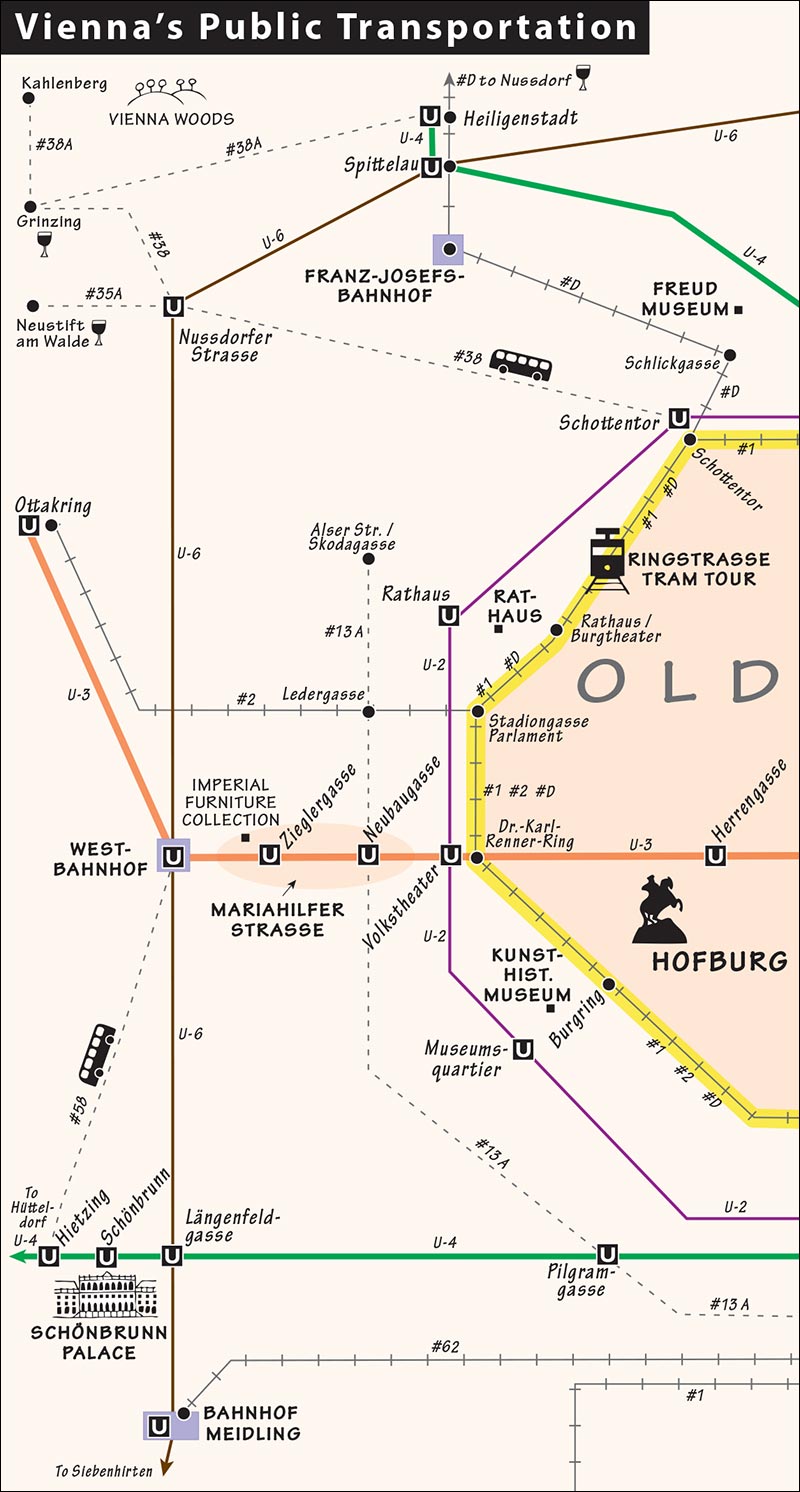

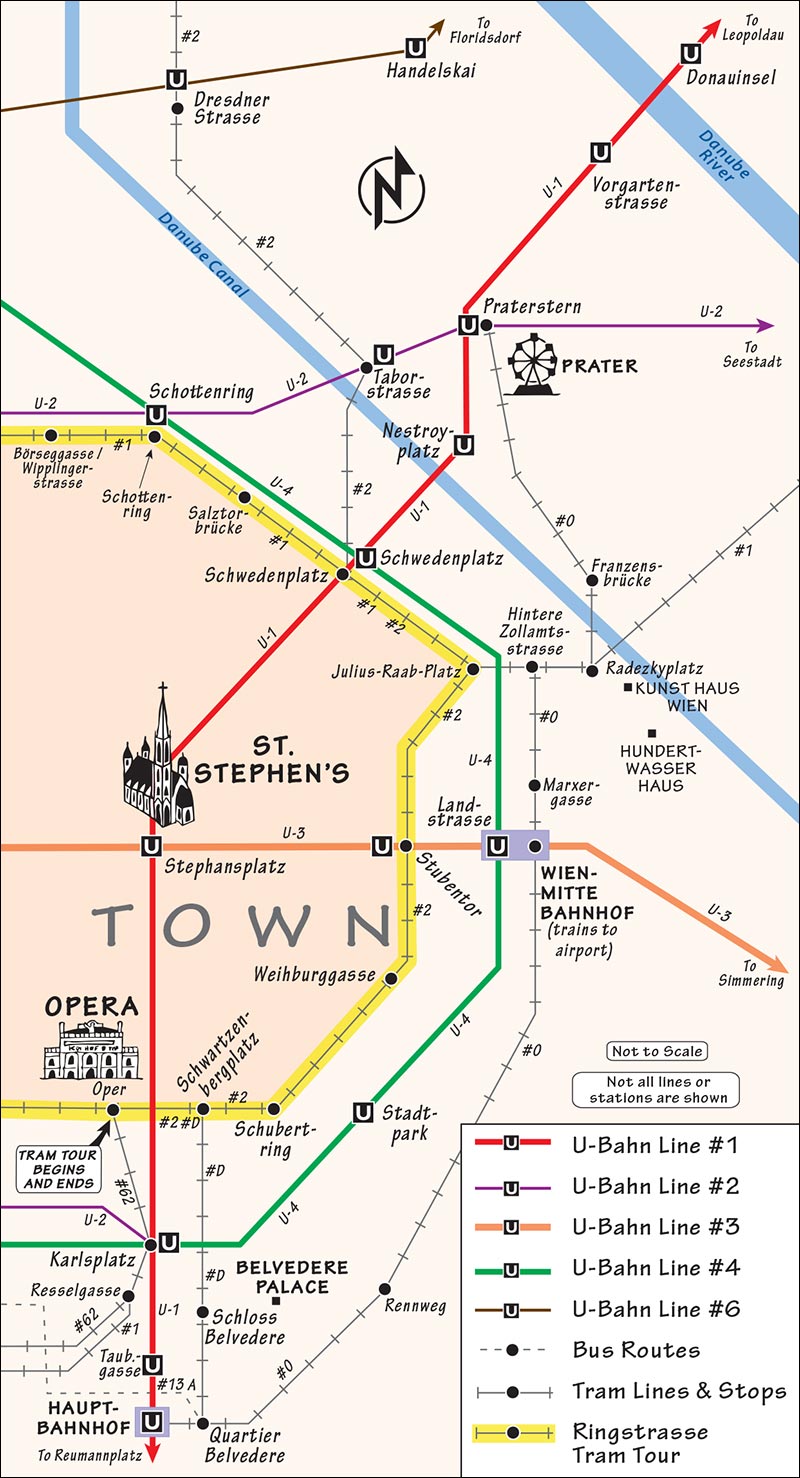

Map: Vienna’s Public Transportation

WITHIN THE RING, IN THE OLD CITY CENTER

ON OR NEAR MARIAHILFER STRASSE

Map: Hotels & Restaurants near Mariahilfer Strasse

CASUAL EATERIES AND TRADITIONAL STANDBYS

Map: Restaurants in Central Vienna

WEIN IN WIEN: VIENNA’S WINE GARDENS

German Survival Phrases for Austria

Vienna is the capital of Austria, the cradle of classical music, the home of the rich Habsburg heritage, and one of the world’s most livable cities. The city center is skyscraper-free, pedestrian-friendly, dotted with quiet parks, and traversed by electric trams. Many buildings still reflect 18th- and 19th-century elegance, when the city was at the forefront of the arts and sciences. Compared with most modern European urban centers, the pace of life is slow.

For much of its 2,500-year history, Vienna (Wien in German—pronounced “veen”) was on the frontier of civilized Europe. Located on the south bank of the Danube, it was threatened by Germanic barbarians (in Roman times), marauding Magyars (today’s Hungarians, 10th century), Mongol hordes (13th century), Ottoman Turks (the sieges of 1529 and 1683), and encroachment by the Soviet Union after World War II.

The Habsburg dynasty ruled their great empire from Vienna, setting the stage for its position as an enduring cultural capital. Among the Hapsburgs, Maria Theresa in the late 1700s was famous for having 16 children and cleverly marrying many of them into royal families around Europe to expand the family’s reach.

Vienna reached its peak in the 19th century, when it was on par with London and Paris in size and importance. Emerging as a cultural powerhouse, it was home to groundbreaking composers (Beethoven, Mozart, Brahms, Strauss), scientists (Doppler, Boltzmann), philosophers (Freud, Husserl, Schlick, Gödel, Steiner), architects (Wagner, Loos), and painters (Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka). By the turn of the 20th century, Vienna was one of the world’s most populous cities and sat on the cusp between stuffy Old World monarchism and subversive modern trends.

After the turmoil of the two world wars and the loss of Austria’s empire, Vienna has settled down into a somewhat sleepy, pleasant place where culture is still king. Classical music is everywhere. People nurse a pastry and coffee over the daily paper at small cafés. It’s a city of world-class museums, big and small. Anyone with an interest in painting, music, architecture, beautiful objects, or Sacher torte with whipped cream will feel right at home.

From a practical standpoint, Vienna serves as a prime gateway city. Its central location is convenient to most major Eastern European destinations. Actually farther east than Prague, Ljubljana, and Zagreb, and just upstream on the Danube from Budapest and Bratislava, Vienna is an ideal launchpad for a journey into the East.

For a big city, Vienna is pleasant and laid-back. Packed with sights, it’s worth two days and two nights on even the speediest trip.

If you’re visiting Vienna as part of a longer European trip, you could sleep on the train on your way in and out—Berlin, Prague, Kraków, Venice, Rome, and Cologne are each handy night trains away.

Palace Choices: The Hofburg and Schönbrunn are both world-class palaces, but seeing both is redundant if your time or money is limited. If you’re rushed and can fit in only one palace, make it the Hofburg. It comes with the popular Sisi Museum and is right in the town center, making for an easy visit. With more time, a visit to Schönbrunn—set outside town amid a grand and regal garden—is also a great experience.

Below is a suggested itinerary for how to spend your daytime sightseeing hours. The best options for evenings are taking in a concert, opera, or other musical event; enjoying a leisurely dinner (and people-watching) in the stately old town or atmospheric Spittelberg quarter; heading out to the Heuriger wine pubs in the foothills of the Vienna Woods; or touring the Haus der Musik interactive music museum (open nightly until 22:00). Plan your evenings based on the schedule of musical events. If you’ve downloaded my audio tours (see “Rick Steves Audio Europe” sidebar on here), the Vienna City Walk works wonderfully in the evening. Whenever you need a break, linger in a classic Viennese café.

| 9:00 | Take the 1.5-hour Red Bus City Tour, or circle the Ringstrasse by tram, to get your bearings. |

| 10:30 | Drop by the TI for planning and ticket needs. |

| 11:00 | Tour the Vienna State Opera (schedule varies, confirm at TI). |

| 14:00 | Follow my Vienna City Walk, including visits to the Kaisergruft and St. Stephen’s Cathedral (nave closes at 16:30, or 18:30 June-Aug). |

| 9:00 | Browse the colorful Naschmarkt. |

| 11:00 | Tour the Kunsthistorisches Museum. |

| 14:00 | Tour the Hofburg Palace Imperial Apartments and Treasury. |

| 10:00 | Visit Belvedere Palace, with its fine Viennese art and great city views. |

| 15:00 | Tour Schönbrunn Palace to enjoy the imperial apartments and grounds. |

| 10:00 | Enjoy (depending on your interests) the engaging Karlsplatz sights (Karlskirche, Wien Museum, Academy of Fine Arts, and the Secession). |

| 14:00 | Do some shopping along Mariahilfer Strasse, or rent a bike and head out to the modern Donau City “downtown” sector, Danube Island (for fun people-watching), and Prater Park (with its amusement park). |

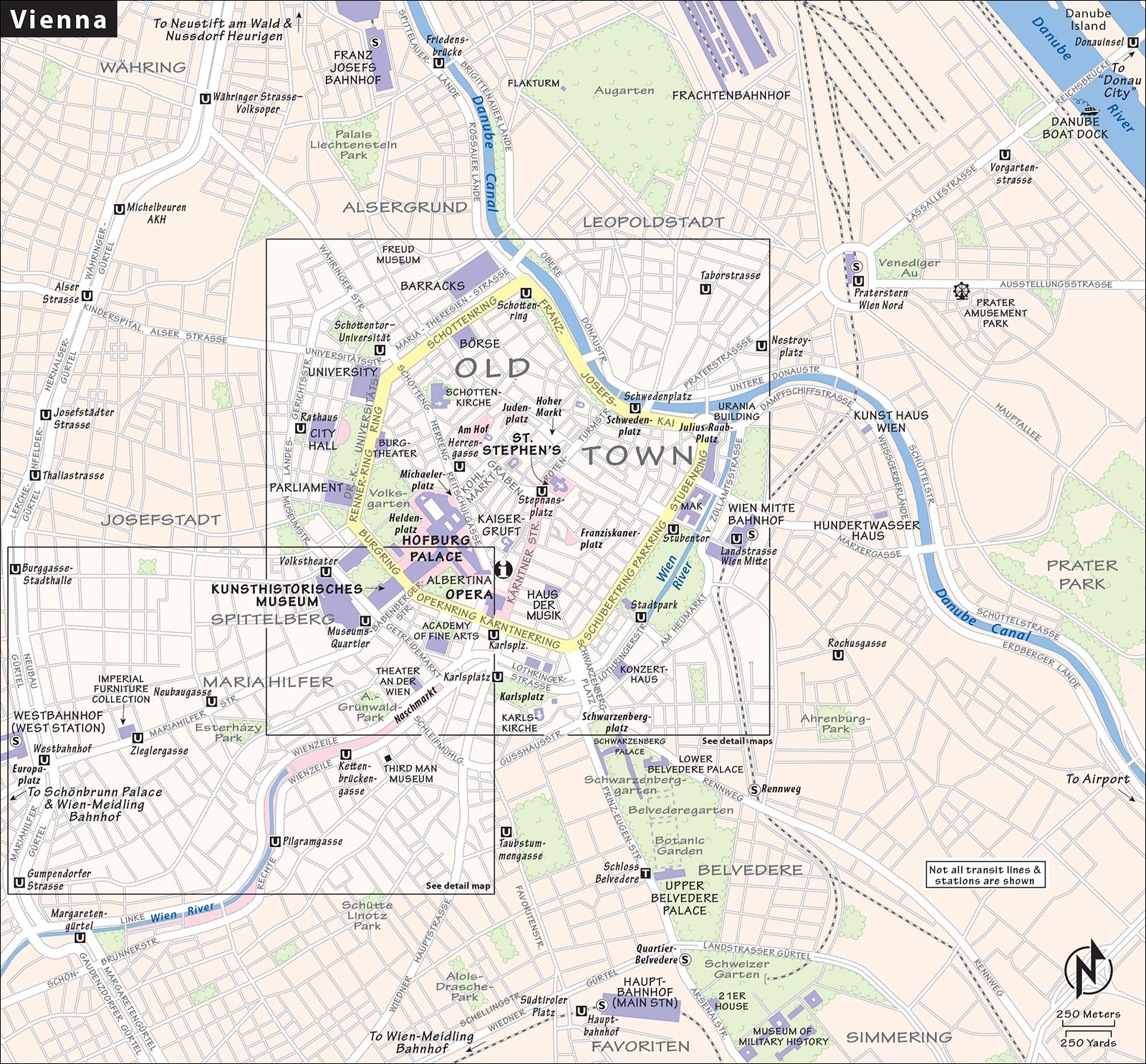

Vienna sits between the Vienna Woods (Wienerwald) and the Danube River (Donau). To the southeast is industrial sprawl. The Alps, which arc across Europe from Marseille, end at Vienna’s wooded hills, providing a popular playground for walking and sipping new wine. This greenery’s momentum carries on into the city. More than half of Vienna is parkland, filled with ponds, gardens, trees, and statue-maker memories of Austria’s glory days.

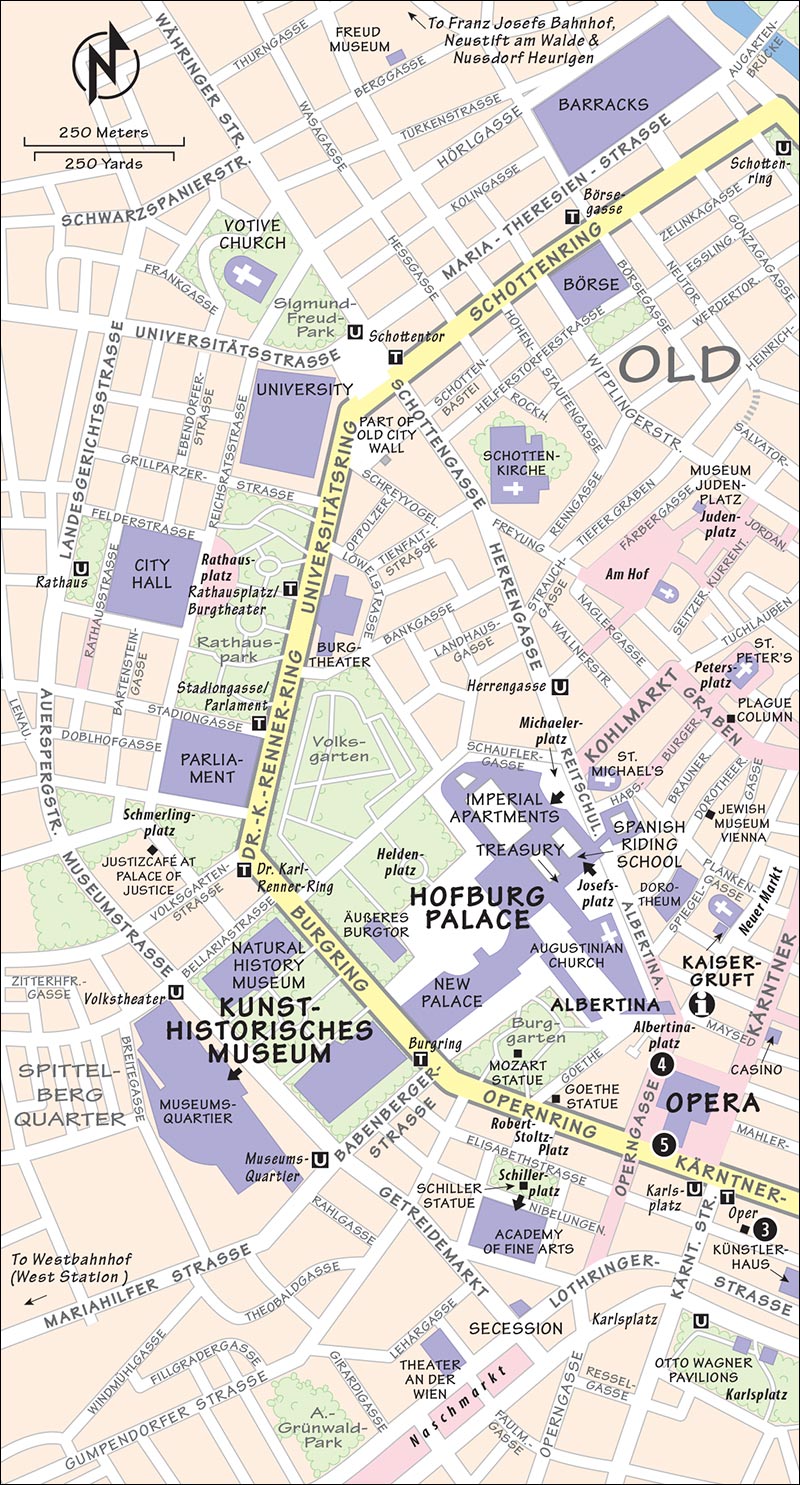

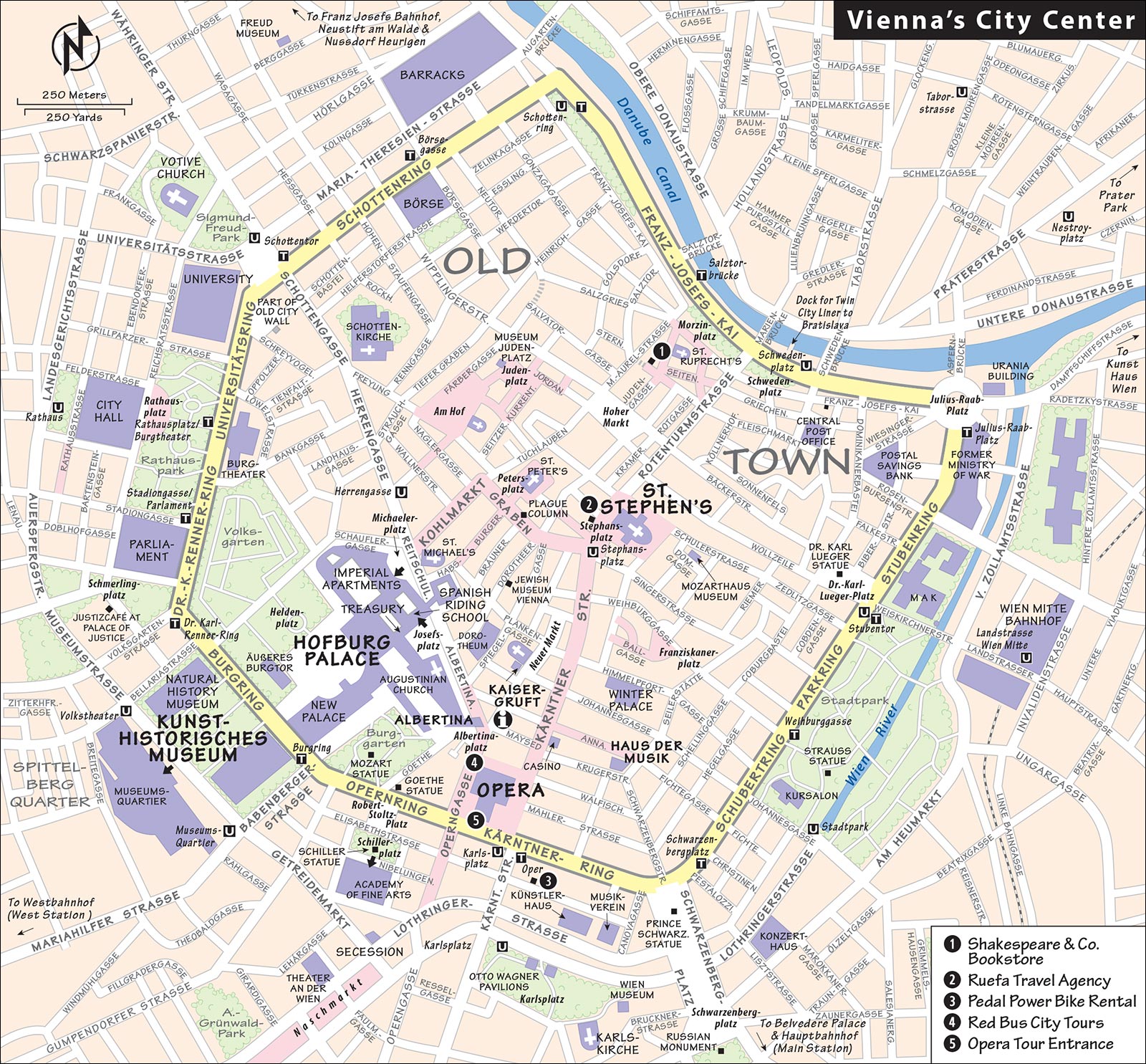

Think of the city map as a target with concentric circles: The bull’s-eye is St. Stephen’s Cathedral, the towering spired church south of the Danube. Surrounding that is the old town, bound tightly by the circular road known as the Ringstrasse, marking what used to be the city wall. The Gürtel, a broader, later ring road, contains the rest of downtown. Outside the Gürtel lies the uninteresting sprawl of modern Vienna.

Much of Vienna’s sightseeing—and most of my recommended restaurants—are located in the old town, inside the Ringstrasse. Walking across this circular area takes about 30 minutes. St. Stephen’s Cathedral sits in the center, at the intersection of the two main (pedestrian-only) streets: Kärntner Strasse and the Graben.

Several sights sit along, or just beyond, the Ringstrasse: To the southwest are the Hofburg and related Habsburg sights, as well as the Kunsthistorisches Museum; to the south is a cluster of intriguing sights near Karlsplatz; to the southeast is Belvedere Palace. A branch of the Danube River borders the Ring to the north.

As a tourist, concern yourself only with this compact old center. When you do, sprawling Vienna becomes easily manageable.

Vienna’s main TI is a block behind the Vienna State Opera at Albertinaplatz (daily 9:00-19:00, free Wi-Fi, theater box office, tel. 01/211-140, www.vienna.info). It’s a rare example of a TI in Europe that is really a service (possible because tourists pay for it with a hotel tax). There are also TIs at the airport (daily 7:00-22:00) and the train station (daily 9:00-19:00).

Look for the monthly program of concerts (called Wien-Programm), the handy Vienna from A to Z booklet, the annual city guide called Vienna Journal, and two good brochures: Walks in Vienna and Architecture from Art Nouveau to the Present. Ask about their program of guided walks (€16 each), and consider buying a Vienna Pass, which includes entry to many sights and lets you skip lines (see here).

For a comprehensive rundown on Vienna’s various train stations and its airport, as well as tips on arriving or departing by boat, see “Vienna Connections,” at the end of this chapter.

Music Sightseeing Priorities: Be wary of Vienna’s various music sights. Many “homes of composers” are pretty disappointing. My advice to music lovers is to take in a concert, tour the Vienna State Opera or snare cheap standing-room tickets to see a performance there, enjoy the Haus der Musik, or scour the wonderful Collection of Ancient Musical Instruments in the Hofburg’s New Palace. If in town on a Sunday, don’t miss the glorious music at the Augustinian Church Mass (see here).

Useful App:  For free audio self-guided tours (Vienna City Walk, St. Stephen’s Cathedral, Ringstrasse Tram Tour), get the Rick Steves Audio Europe app (for details, see here).

For free audio self-guided tours (Vienna City Walk, St. Stephen’s Cathedral, Ringstrasse Tram Tour), get the Rick Steves Audio Europe app (for details, see here).

Post Offices: The main post office is near Schwedenplatz at Fleischmarkt 19 (open daily). Convenient branch offices are at the Hauptbahnhof (closed Sun), Westbahnhof (closed Sun), and near the opera house (closed Sat-Sun, Krugerstrasse 13).

English Bookstore: Stop by the woody and cool Shakespeare & Co., in the historic and atmospheric Ruprechtsviertel district near the Danube Canal (Mon-Fri 9:00-21:00, Sat 9:00-20:00, closed Sun, north of Hoher Markt at Sterngasse 2, tel. 01/535-5053, www.shakespeare.co.at). See the map on here.

Laundry: Schnell & Sauber Waschcenter is big, has free Wi-Fi, and is conveniently located close to Mariahilfer Strasse accommodations and easily reached from downtown by U-Bahn (daily 6:00-24:00, Westbahnstrasse 60, U: Burggasse/Stadthalle, or take tram #49 to Urban-Loritz-Platz, see map on here, mobile 0660-760-4546, www.schnellundsauber.at).

Travel Agency: Conveniently located on Stephansplatz, Ruefa sells tickets for flights, trains, and boats to Bratislava. They’ll waive the €8 service charge for train and boat tickets for my readers (Mon-Fri 9:00-18:30, closed Sat-Sun, Stephansplatz 10, tel. 01/513-4524, Gertrude and Sandra speak English).

Toll Sticker: Austria charges drivers to use its major roads. You’ll need a Vignette sticker stuck to the inside of your rental car’s windshield (buy at the border crossing, big gas stations near borders, or a rental-car agency; www.asfinag.at). The cost is €9 for 10 days, or €26 for two months. Not having one earns you a stiff fine.

(See “Vienna’s Public Transportation” map, here.)

Take full advantage of Vienna’s efficient transit system, which includes trams, buses, U-Bahn (subway), and S-Bahn (faster suburban) trains. It’s fast, clean, and easy to navigate.

I generally stick to the tram to zip around the Ring (trams #1, #2, #D, and #O) and take the U-Bahn to outlying sights, hotels, and Vienna's train stations (see map on here). There are five color-coded U-Bahn lines: U-1 red, U-2 purple, U-3 orange, U-4 green, and U-6 brown. If you see a bus number that starts with N (such as #N38), it’s a night bus, which operates after other public transit stops running. Transit info: tel. 01/790-9100, www.wienerlinien.at.

Tickets and Passes: Trams, buses, and the U-Bahn and S-Bahn all use the same tickets. Except on days spent entirely within the Ring, buying a single- or multiday pass is usually a good investment (and pays off if you take at least four trips). Many people find that once they have a pass, they end up using the system more.

Buy tickets from vending machines in stations (marked Fahrkarten/Ticket, easy and in English), from Vorverkauf offices in stations, or on trams or buses (single tickets only). You have lots of choices:

• Single tickets (€2.20, €2.30 on tram or bus, good for one journey with necessary transfers)

• 24-hour transit pass (€7.60)

• 48-hour transit pass (€13.30)

• 72-hour transit pass (€16.50)

• 7-day transit pass (Wochenkarte, €16.20—the catch is that the pass runs from Monday to Monday, so you may get less than seven days of use)

• 8-day “Climate Ticket” (Acht-Tage-Klimakarte, €38.40, can be shared—for example, four people for two days each).

Transit Tips: To get your bearings on buses, trams, the U-Bahn, and the S-Bahn, you’ll want to know the end-of-the-line stop in the direction that you’re heading. For example, if you're in the city center at Stephansplatz and you want to take the U-Bahn to the main train station (Hauptbahnhof), you'd take U-1 going in the direction "Reumannplatz."

You must stamp your ticket at the barriers in U-Bahn and S-Bahn stations, and in the machines on trams and buses (stamp multiple-use passes only the first time you board). Cheaters pay a stiff fine (about €100), plus the cost of the ticket.

On trams, stop announcements are voice-only and easy to miss—carry a map. Rookies miss stops because they fail to open the door. Push buttons, pull latches—do whatever it takes.

Before you exit a U-Bahn station, study the wall-mounted street map. Choosing the right exit—signposted from the moment you step off the train—saves lots of walking.

Cute little electric buses wind through the tangled old center (from Schottentor to Stubentor). Bus #1A is best for a joyride—hop on and see where it takes you.

Vienna’s comfortable, civilized, and easy-to-flag-down taxis start at €3.80 (higher rates at night). You’ll pay about €10 to go from the opera house to the Hauptbahnhof. Pay only what’s on the meter—the only legitimate surcharges are for calling a cab (€3) or for riding to the airport (€13).

If you like Uber, the ride service (and your app) works in Vienna just like it does in the US.

Consider the luxury of having your own car and driver. Johann (a.k.a. John) Lichtl is a gentle, honest, English-speaking cabbie who can take up to four passengers in his car (€27/1 hour, €25/hour for 2 hours or more, €27 to or from airport, mobile 0676-670-6750). Consider a custom-tailored city driving tour (2 hours), a day trip to the Danube Valley (€160), or a visit to the Mauthausen Memorial with a little Danube sightseeing en route (€240).

With more than 600 miles of bike lanes (and a powerful Green Party), Vienna is a great city on two wheels. Consider using a rental bike for the duration of your visit (Pedal Power bike rental does hotel delivery and pickups; see next page). Just park your bike at the hotel, and you’ll go anywhere in town faster than a taxi can take you. Biking (carefully) through Vienna’s many traffic-free spaces is no problem. And bikes ride the U-Bahn for free (but aren’t allowed during weekday rush hours).

The bike path along the Ring is wonderfully entertaining—you’ll enjoy the shady parklike ambience of the boulevard while rolling by many of the city’s top sights.

Besides the Ring, your best sightseeing by bike is through Stadtpark (City Park), across Danube Island, and out to the modern Donau City business district. These routes are easy to follow on the free tourist city map available from the TI (some routes can also be downloaded from the TI website). Red-colored pavement is the usual marking for bike lanes, but some bike lanes are marked just with white lines.

Borrowing a Free/Cheap Bike: Citybike Wien lets you borrow bikes from public racks all over town (toll tel. 0810-500-500, www.citybikewien.at). The three-speed bikes are heavy and clunky (with solid tires to discourage thieves)—and come with a basket, built-in lock, and ads on the side—but they’re perfect for a short, practical joyride in the center (such as around the Ringstrasse).

The system is easy to use. Bikes are locked into more than 100 stalls scattered through the city center. To borrow one, register your credit card at the terminal at any rack, create a password (save it for future rentals), then unlock a bike (you can also register online at www.citybikewien.at). First-time registration is €1 (only one bike per credit card—couples must use two different cards). Since the bikes are designed for short-term use, it costs more per hour the longer you keep it (first hour-free, second hour-€1, third hour-€2, €4/hour after that). When you’re done, drop off your bike at any stall.

Renting a Higher-Quality Bike: If you want to ride beyond the town center—or you simply want a better set of wheels—rent from Pedal Power (€6/hour, €19/4 hours, €30/24 hours, 10 percent discount with this book, daily May-Sept 8:30-18:00, shorter hours April and Oct, rental office near Prater Park, U: Praterstern, then walk 100 yards to Ausstellungsstrasse 3—see map on here, tel. 01/729-7234, www.pedalpower.at). For €5 extra they’ll deliver a bike to your hotel and pick it up when you’re done (service available year-round). They also organize bike tours (described later).

To sightsee on your own, download my free audio tours that illuminate some of Vienna's top sights and neighborhoods, including my Vienna City Walk and tours of St. Stephen’s Cathedral and the Ringstrasse. The City Walk and Ringstrasse tram tour start at the opera house and work nicely in the evening as well as during the day. The cathedral tour can be spliced into the city walk for efficiency (for more on these audio tours, see the sidebar on here).

To sightsee on your own, download my free audio tours that illuminate some of Vienna's top sights and neighborhoods, including my Vienna City Walk and tours of St. Stephen’s Cathedral and the Ringstrasse. The City Walk and Ringstrasse tram tour start at the opera house and work nicely in the evening as well as during the day. The cathedral tour can be spliced into the city walk for efficiency (for more on these audio tours, see the sidebar on here).

A basic 1.5-hour “Vienna at First Glance” introductory walk is offered daily throughout the summer (€16, leaves at 14:00 from in front of the main TI, just behind the opera house, in English and German, just show up, tel. 01/774-8901, www.wienguide.at).

This company offers a “pay what you like” 2.5-hour walk through the city center. While my Vienna City Walk is much more succinct, this can be an entertaining ramble with a local telling stories of the city. Reserve online or just show up (pay what you think it’s worth at the end—no coins, paper only, daily departures at 10:00 and 14:00, maximum 35 people, meet at fountain at tip of Albertina across from TI, mobile 0664/554-4315, www.goodviennatours.eu).

Consider a bus tour, bike tour, or even one by horse-and-buggy.

Big convertible buses make a 1.5-hour loop around the city, hitting the highlights with a 20-minute shopping break in the middle. They cover the main attractions along with the entire Ringstrasse, and then zip through Prater Park, over the Danube for a glimpse of the city’s Danube Island playground, and into the Donau City skyscraper zone. If the weather’s good, the bus goes topless and offers great opportunities for photos (€15 ticket from driver, buses leave from Albertinaplatz 2, opposite the TI behind the opera house; hourly departures April-Oct 10:00-18:00, Nov-March at 11:00, 13:00, and 15:00; pretty good recorded narration in any language, tel. 01/512-4030, www.redbuscitytours.at, Gabriel).

Their 3.5-hour city tour includes Schönbrunn Palace (€47, 2/day). They also run hop-on, hop-off bus tours with recorded commentary (three one-hour routes, €17/route, departs from opera house, www.viennasightseeing.at). If you just want a quick guided city tour, take the Red Bus tours recommended above.

One of Europe’s great streets, the Ringstrasse is lined with many of the city’s top sights. Take a tram ride around the ring with my free audio tour (see here), which gives you a fun orientation and a ridiculously quick glimpse of some major sights as you glide by. Neither tram #1 nor #2 makes the entire loop around the Ring, but you can see it all by making one transfer between them (at the Schwedenplatz stop). You can use a single transit ticket to cover the whole route, including the transfer (though you can’t interrupt your trip, except to transfer). For more on riding Vienna’s trams, see earlier, under “Getting Around Vienna.”

The Vienna Ring Tram, a yellow made-for-tourists streetcar, is an easier though pricier option, running clockwise along the entire Ringstrasse (€9 for 30-minute loop, 2/hour 10:00-17:30, recorded narration, www.wienerlinien.at). The 25-minute tour starts every half-hour at Schwedenplatz. At each stop, you’ll see a sign for this tram tour (look for VRT Ring-Rund Sightseeing). The schedule notes the next departure time.

Tours cover the central district in three hours and go twice daily from May to September (€29/tour includes bike, €15 extra to keep bike for the day, ask about Rick Steves discount, English tours depart at 10:00 across the Ring from the opera house at Bösendorferstrasse 5, tel. 01/729-7234, www.pedalpower.at). They also rent bikes and offer Segway tours daily in summer.

These traditional horse-and-buggies, called Fiaker, take rich romantics on clip-clop tours lasting 20 minutes (Old Town-€55), 40 minutes (Old Town and the Ring-€80), or one hour (all the above, but more thorough-€110). You can share the ride and cost with up to five people. Because it’s a kind of guided tour, talk to a few drivers before choosing a carriage, and pick someone who’s fun and speaks English (tel. 01/401-060).

Vienna becomes particularly vivid and meaningful with the help of a private guide. I’ve enjoyed working with these guides; any of them can set you up with another good guide if they are already booked.

Lisa Zeiler is a good storyteller with years of guiding experience (€150/2-3 hours, mobile 0699-1203-7550, lisa.zeiler@gmx.at). Wolfgang Höfler, a generalist with a knack for having psychoanalytical fun with history, enjoys the big changes of the 19th and 20th centuries. He’ll take you around on foot or by bike (€160/2 hours, €50 for each additional hour, bike tours—€160/3 hours, mobile 0676-304-4940, www.vienna-aktivtours.com, office@vienna-aktivtours.com). Adrienn Bartek-Rhomberg offers themed walks in the city as well as Schönbrunn Palace tours (€150/3 hours, €300/full day, €280 “Panorama City Tour”—a minibus and walking tour for up to six people, mobile 0650-826-6965, www.experience-vienna.at, office@experience-vienna.at). Gerhard Strassgschwandtner, who runs the Third Man Museum (see here), is passionate about history in all its marvelous complexity (€160/2 hours, mobile 0676-475-7818, www.special-vienna.com, gerhard@special-vienna.com).

11 Graben

14 Loos’ Loos

15 Kohlmarkt

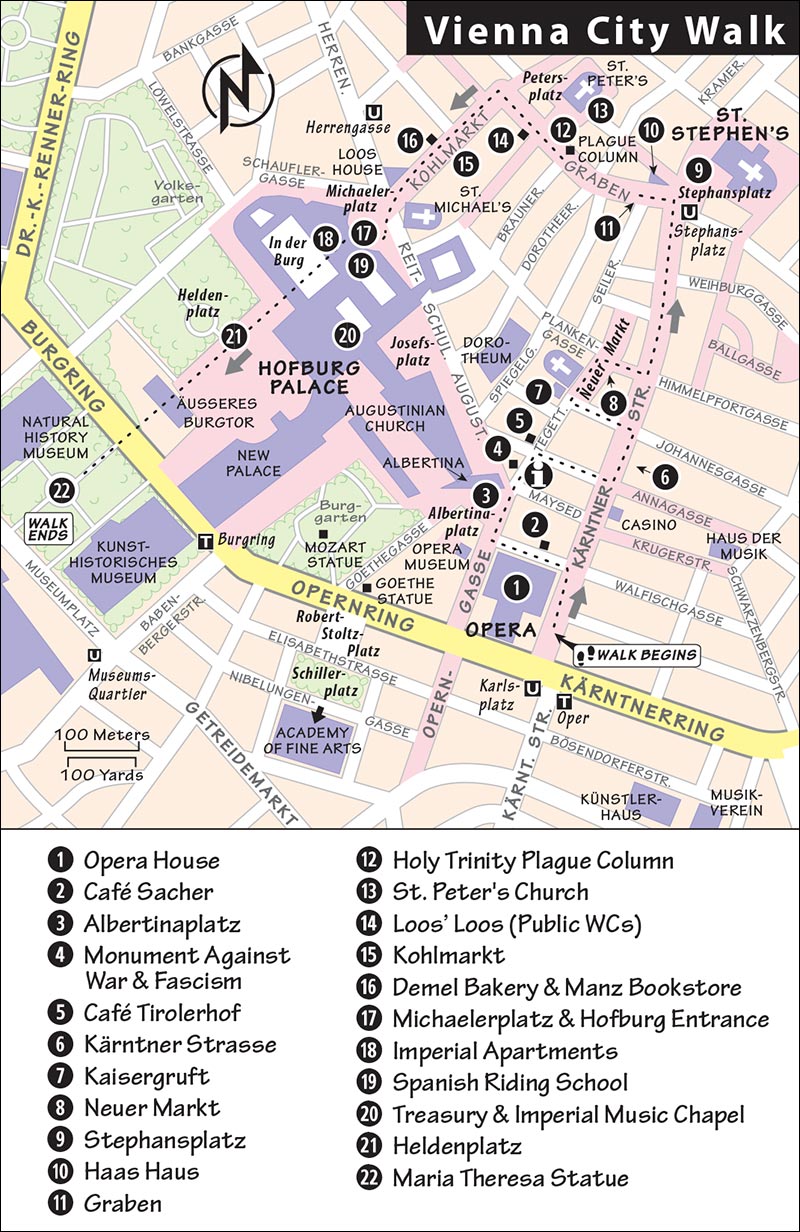

(See “Vienna City Walk” map, here.)

This self-guided walk connects the top three sights in Vienna’s old center: the Vienna State Opera, St. Stephen’s Cathedral, and Hofburg Palace. These and many of the other sights you’ll see along this walk are covered in more detail elsewhere in this chapter (flip to “Sights in Vienna,” later).

Length of This Walk: Allow one hour for the walk alone, and more time if you plan to stop at any major sights along the way.

When to Go: This walk works just as well in the evening as it does during the day, as long as you don’t plan on touring some of the sights along the way.

Tours:  Download my free Vienna City Walk audio tour. For efficiency, you can splice my St. Stephen’s Cathedral audio tour into this walk.

Download my free Vienna City Walk audio tour. For efficiency, you can splice my St. Stephen’s Cathedral audio tour into this walk.

SELF-GUIDED WALK

SELF-GUIDED WALK• Begin at the square outside Vienna’s landmark opera house, home of the Vienna State Opera. (The entrance faces the Ringstrasse; we’re starting at the busy pedestrian square that’s to the right of the entrance as you’re facing it.)

If Vienna is the world capital of classical music, this building is its throne room, one of the planet’s premier houses of music. It’s typical of Vienna’s 19th-century buildings in that it features a revival style—Neo-Renaissance—with arched windows, half-columns, and the sloping, copper mansard roof typical of French Renaissance châteaux.

Since the structure was built in 1869, almost all of the opera world’s luminaries have passed through here. Its former musical directors include Gustav Mahler, Herbert von Karajan, and Richard Strauss. Luciano Pavarotti, Maria Callas, Placido Domingo, and many other greats have sung from its stage.

In the pavement along the side of the opera house (and all along Kärntner Strasse, the bustling shopping street we’ll visit shortly), you’ll find star plaques forming a Hollywood-style walk of fame. These represent the stars of classical music—famous composers, singers, musicians, and conductors.

Looking up at the opera, notice the giant outdoor screen onto which some live performances are projected (as noted in the posted schedules and on the screen itself).

If you’re a fan, take a guided tour of the opera. Or consider springing for an evening performance (standing-room tickets are surprisingly cheap; see here). Regular opera tickets are sold at various points near here: The closest ticket office is the small one just below the screen, while the main one is on the other side of the building, across the street on Operngasse. For information about other entertainment options during your visit, check in at the Wien Ticket kiosk in the booth on this square.

The opera house marks a busy intersection in Vienna, where Kärntner Strasse meets the Ring. The Karlsplatz U-Bahn station in front of the opera is an underground shopping mall with fast food, newsstands, and lots of pickpockets.

• Walk behind the opera and across the street toward the dark-red awning to find the famous...

This is the home of the world’s classiest chocolate cake, the Sacher torte: two layers of cake separated by apricot jam and covered in dark-chocolate icing, usually served with whipped cream. It was invented in a fit of improvisation in 1832 by Franz Sacher, dessert chef to Prince Metternich (the mastermind diplomat who redrew the map of post-Napoleonic Europe). The cake became world famous when the inventor’s son served it next door at his hotel (you may have noticed the fancy doormen). Many locals complain that the cakes here have gone downhill, and many tourists are surprised by how dry they are—you really need that dollop of Schlagobers. Still, coffee and a slice of cake here can be €8 well invested for the history alone (daily 8:00-24:00). While the café itself is grotesquely touristy, the adjacent Sacher Stube has ambience and natives to spare (same prices, daily 10:00-24:00). For maximum elegance, sit inside.

• Continue past Hotel Sacher. At the end of the street is a small, triangular, cobbled square adorned with memorial sculptures.

As you approach the square, to the right you’ll find the TI.

On your left, the tan-and-white Neoclassical building with the statue alcoves marks the tip of the Hofburg Palace—the sprawling complex of buildings that was long the seat of Habsburg power (we’ll end this walk at the palace’s center). The balustraded terrace up top was originally part of Vienna’s defensive rampart. Later, it was the balcony of Empress Maria Theresa’s daughter Maria Christina, who lived at this end of the palace. Today, her home houses the Albertina Museum, topped by a sleek, controversial titanium canopy (called the “diving board” by critics). The museum’s plush, 19th-century state rooms are the only Neoclassical (post-Rococo) palace rooms anywhere in the Habsburg realm. And the Batliner Collection of modernist paintings (Monet to Picasso) is a delight.

Albertinaplatz itself is filled with sculptures that make up the powerful, thought-provoking 4 Monument Against War and Fascism, which commemorates the dark years when Austria came under Nazi rule (1938-1945).

The memorial has four parts. The split white monument, The Gates of Violence, remembers victims of all wars and violence. Standing directly in front of it, you’re at the gates of a concentration camp. Then, as you explore the statues, you step into a montage of wartime images: clubs and WWI gas masks, a dying woman birthing a future soldier, victims of cruel medical experimentation, and chained slave laborers sitting on a pedestal of granite cut from the infamous quarry at Mauthausen concentration camp (located not far from Vienna). The hunched-over figure on the ground behind is a Jew forced to scrub anti-Nazi graffiti off a street with a brush. Of Vienna’s 200,000 Jews, more than 65,000 died in Nazi concentration camps. The sculpture with its head buried in the stone is Orpheus entering the underworld, meant to remind Austrians (and the rest of us) of the victims of Nazism...and the consequences of not keeping our governments on track. Behind that, the 1945 declaration that established Austria’s second republic—and enshrined human rights—is cut into the stone.

Viewing this monument gains even more emotional impact when you realize what happened on this spot: During a WWII bombing attack, several hundred people were buried alive when the cellar they were using as shelter was demolished.

Austria was led into World War II by Germany, which annexed the country in 1938 with disturbingly little resistance, saying Austrians were wannabe Germans anyway. But Austrians are not Germans (this makes for an interesting topic of conversation with Austrians you may meet). They’re quick to proudly tell you that Austria was founded in the 10th century, whereas Germany wasn’t born until 1870. For seven years just before and during World War II (1938-1945), there was no Austria. In 1955, after 10 years of joint occupation by the victorious Allies, Austria regained total independence on the condition that it would be forever neutral (and never join NATO or the Warsaw Pact). To this day, Austria is outside of NATO (and Germany).

Behind the monument is 5 Café Tirolerhof, a classic Viennese café. Refreshingly air-conditioned, it’s full of things that time has passed by: chandeliers, marble tables, upholstered booths, waiters in tuxes, and newspapers. For more on Vienna’s cafés, see here.

This square is where many of the city’s walking tours and bus tours start. You may see Red Bus City Tour buses, which offer a handy way to get a quick overview of the city (see “Tours in Vienna,” earlier).

• From the café, turn right on Führichsgasse. Walk one block until you hit...

This grand, traffic-free street is the people-watching delight of this in-love-with-life city. Today’s Kärntner Strasse (KAYRNT-ner SHTRAH-seh) is mostly a crass commercial pedestrian mall—its famed elegant shops long gone. But locals know it’s the same road Crusaders marched down as they headed off from St. Stephen’s Cathedral for the Holy Land in the 12th century. Its name indicates that it leads south, toward the region of Kärnten (Carinthia, a province divided between Austria and Slovenia). Today it’s full of shoppers and street musicians.

Where Führichsgasse meets Kärntner Strasse, note the city Casino (across the street and a half-block to your right, at #41)—once venerable, now tacky, it exemplifies the worst of the street’s evolution. Turn left to head up Kärntner Strasse, going away from the opera house. As you walk along, be sure to look up, above the modern storefronts, for glimpses of the street’s former glory. Near the end of the block, on the left at #26, J & L Lobmeyr Crystal (“Founded in 1823”) still has its impressive brown storefront with gold trim, statues, and the Habsburg double-eagle. In the market for some $400 napkin rings? Lobmeyr’s your place. Inside, breathe in the classic Old World ambience as you climb up to the glass museum (free entry, closed Sun).

• At the end of the block, turn left on Marco d’Aviano Gasse (passing the fragrant flower stall) to make a short detour to the square called Neuer Markt. Straight ahead is an orange-ish church with a triangular roof and cross, the Capuchin Church. In its basement is the...

Under the church sits the Imperial Crypt, filled with what’s left of Austria’s emperors, empresses, and other Habsburg royalty. For centuries, Vienna was the heart of a vast empire ruled by the Habsburg family, and here is where they lie buried in their fancy pewter coffins. You’ll find all the Habsburg greats, including Maria Theresa, her son Josef II (Mozart’s patron), Franz Josef, and Empress Sisi. Before moving on, consider paying your respects here.

• Stretching north from the Kaisergruft is the square called...

A block farther down, in the center of Neuer Markt, is the four rivers fountain showing Lady Providence surrounded by figures symbolizing the rivers that flow into the Danube. The sexy statues offended Empress Maria Theresa, who actually organized “Chastity Commissions” to defend her capital city’s moral standards. The modern buildings around you were rebuilt after World War II. Half of the city’s inner center was intentionally destroyed by Churchill to demoralize the Viennese, who were disconcertingly enthusiastic about the Nazis.

• Lady Providence’s one bare breast points back to Kärntner Strasse (50 yards away), where you’ll turn left. Continuing down Kärntner Strasse, you’ll find lots of shops filled with merchandise proven to entice tourists. Pass the U-Bahn station (which has WCs) where the street spills into Vienna’s main square...

The cathedral’s frilly spire looms overhead, worshippers and tourists pour inside the church, and shoppers buzz around the outside. You’re at the center of Vienna.

The Gothic St. Stephen’s Cathedral (c. 1300-1450) is known for its 450-foot south tower, its colorful roof, and its place in Viennese history. When it was built, it was a huge church for what was then a tiny town, and it helped put the fledgling city on the map. At this point, you may want to take a break from the walk to tour the church (for details on visiting the church, see here).

The red-and-white bricks embedded in the pavement in the square show where several earlier churches once stood. The 13th-century Virgilkapelle, with one of the best-preserved Gothic interiors in Vienna, actually survives underground and can be seen through a window just behind the WC in the subway station beneath your feet (escalator nearby).

Where Kärntner Strasse hits Stephansplatz, the grand, soot-covered building with red columns is the Equitable Building (filled with lawyers, bankers, and insurance brokers). It’s a fine example of Neoclassicism from the turn of the 20th century—look up and imagine how slick Vienna must have felt in 1900.

Facing St. Stephen’s is the sleek concrete-and-glass 10 Haas Haus, a postmodern building by noted Austrian architect Hans Hollein (finished in 1990). The curved facade is supposed to echo the Roman fortress of Vindobona (its ruins were found near here). Although the Viennese initially protested having this stark modern tower right next to their beloved cathedral, since then, it’s become a fixture of Vienna’s main square. Notice how the smooth, rounded glass reflects St. Stephen’s pointy architecture, providing a great photo opportunity—especially at twilight.

• Exit the square with your back to the cathedral. Walk past the Haas Haus, and bear right down the street called the...

This was once a Graben, or ditch—originally the moat for the Roman military camp. Back during Vienna’s 19th-century heyday, there were nearly 200,000 people packed into the city’s inner center (inside the Ringstrasse), walking through dirt streets. Today this area houses 20,000. The Graben was a busy street with three lanes of traffic until the 1970s, when the city inaugurated its new subway system and the street was turned into one of Europe’s first pedestrian-only zones. Take a moment to absorb the scene—you’re standing in an area surrounded by history, postwar rebuilding, grand architecture, fine cafés, and people enjoying life...for me, quintessential Europe.

Eventually, you reach Dorotheergasse, on your left, which leads (after two more long blocks) to the Dorotheum auction house. Consider poking your nose in here later for some fancy window shopping. Also along this street are two recommended eateries: the sandwich shop Buffet Trześniewski—one of my favorite places for lunch—and the classic Café Hawelka.

In the middle of the Graben pedestrian zone is the extravagantly blobby 12 Holy Trinity plague column (Pestsäule). The 60-foot pillar of clouds sprouts angels and cherubs, with the wonderfully gilded Father, Son, and Holy Ghost at the top (all protected by an anti-pigeon net).

In 1679, Vienna was hit by a massive epidemic of bubonic plague. Around 75,000 Viennese died—about a third of the city. Emperor Leopold I dropped to his knees (something emperors never did in public) and begged God to save the city. (Find Leopold about a quarter of the way up the monument, just above the brown banner. Hint: The typical inbreeding of royal families left him with a gaping underbite.) His prayer was heard by Lady Faith (the statue below Leopold, carrying a cross). With the help of a heartless little cupid, she tosses an old naked woman—symbolizing the plague—into the abyss and saves the city. In gratitude, Leopold vowed to erect this monument, which became a model for other cities ravaged by the same plague.

• Thirty yards past the plague monument, look down the short street to the right, which frames a Baroque church with a stately green dome.

Leopold I ordered this church to be built as a thank-you for surviving the 1679 plague. The church stands on the site of a much older structure that may have been Vienna’s first (or second) Christian church. Inside, St. Peter’s shows Vienna at its Baroque best. Note that the church offers free organ concerts (advertised at the entry).

• Continue west on the Graben, where you’ll immediately find some stairs leading underground to...

In about 1900, a local chemical maker needed a publicity stunt to prove that his chemicals really got things clean. He purchased two wine cellars under the Graben and had them turned into classy WCs in the Modernist style (designed by turn-of-the-20th-century architect Adolf Loos), complete with chandeliers and finely crafted mahogany. While the chandeliers are gone, the restrooms remain a relatively appealing place to do your business. Locals and tourists happily pay €0.50 for a quick visit.

• The Graben dead-ends at the aristocratic supermarket Julius Meinl am Graben. From here, you could turn right into Vienna’s “golden corner,” with the city’s finest shops. But we’ll turn left. In the distance is the big green-and-gold dome of the Hofburg, where we’ll head soon. The street leading up to the Hofburg is...

This is Vienna’s most elegant and unaffordable shopping street, lined with Cartier, Armani, Gucci, Tiffany, and the emperor’s palace at the end. Strolling Kohlmarkt, daydream about the edible window displays at 16 Demel, the ultimate Viennese chocolate shop (#14, daily 9:00-19:00). The room is filled with Art Nouveau boxes of Empress Sisi’s choco-dreams come true: Kandierte Veilchen (candied violet petals), Katzenzungen (cats’ tongues), and so on. The cakes here are moist (compared to the dry Sacher tortes). The enticing window displays change monthly, reflecting current happenings in Vienna.

Wander inside. There’s an impressive cancan of Vienna’s most beloved cakes—displayed to tempt visitors into springing for the €10 cake-and-coffee deal (point to the cake you want). Farther in, you can see the bakery in action. Sit inside, with a view of the cakemaking, or outside, with the street action (upstairs is less crowded). Shops like this boast “K.u.K.”—signifying that during the Habsburgs’ heyday, it was patronized by the König und Kaiser (king and emperor—same guy). If you happen to be looking through Demel’s window at exactly 19:01, just after closing, you can witness one of the great tragedies of modern Europe: the daily dumping of its unsold cakes.

Next to Demel, the Manz Bookstore has a Loos-designed facade.

• Kohlmarkt ends at the square called...

This square is dominated by the Hofburg Palace. Study the grand Neo-Baroque facade, dating from about 1900. The four heroic giants illustrate Hercules wrestling with his great challenges (Emperor Franz Josef, who commissioned the gate, felt he could relate). In the center of this square, a scant bit of Roman Vienna lies exposed just beneath street level.

Spin Tour: Do a slow, clockwise pan to get your bearings, starting (over your left shoulder as you face the Hofburg) with St. Michael’s Church, which offers fascinating tours of its crypt. To the right of that is the fancy Loden-Plankl shop, with traditional Austrian formalwear, including dirndls. Farther to the right, across Augustinerstrasse, is the wing of the palace that houses the Spanish Riding School and its famous white Lipizzaner stallions. Farther down this street lies Josefsplatz, with the Augustinian Church, and the Dorotheum auction house. At the end of the street are Albertinaplatz and the opera house (where we started this walk).

Continue your spin: Two buildings over from the Hofburg (to the right), the modern Loos House (now a bank) has a facade featuring a perfectly geometrical grid of square columns and windows. Compared to the Neo-Rococo facade of the Hofburg, the stern Modernism of the Loos House appears to be from an entirely different age. And yet, both of these—as well as the Eiffel Tower and Mad Ludwig’s fairy-tale Neuschwanstein Castle—were built in the same generation, roughly around 1900. In many ways, this jarring juxtaposition exemplifies the architectural turmoil of the turn of the 20th century, and represents the passing of the torch from Europe’s age of divine monarchs to the modern era.

• Let’s take a look at where Austria’s glorious history began—at the...

This is the complex of palaces where the Habsburg emperors lived out their lives (except in summer, when they resided at Schönbrunn Palace). Enter the Hofburg through the gate, where you immediately find yourself beneath a big rotunda (the netting is there to keep birds from perching). The doorway on the right is the entrance to the 18 Imperial Apartments, where the Habsburg emperors once lived in chandeliered elegance. Today you can tour its lavish rooms, as well as a museum about Empress Sisi, and a porcelain and silver collection. To the left is the ticket office for the 19 Spanish Riding School.

Continuing on, you emerge from the rotunda into the main courtyard of the Hofburg, called In der Burg. The Caesar-like statue is of Habsburg Emperor Franz II (1768-1835), grandson of Maria Theresa, grandfather of Franz Josef, and father-in-law of Napoleon. Behind him is a tower with three kinds of clocks (the yellow disc shows the phase of the moon tonight). To the right of Franz are the Imperial Apartments, and to the left are the offices of Austria’s mostly ceremonial president (the more powerful chancellor lives in a building just behind this courtyard).

Franz Josef faces the oldest part of the palace. The colorful red, black, and gold gateway (behind you), which used to have a drawbridge, leads over the moat and into the 13th-century Swiss Court (Schweizerhof), named for the Swiss mercenary guards once stationed there. Study the gate. Imagine the drawbridge and the chain. Notice the Habsburg coat of arms with the imperial eagle above and the Renaissance painting on the ceiling of the passageway.

As you enter the Gothic courtyard, you’re passing into the historic core of the palace, the site of the first fortress, and, historically, the place of last refuge. Here you’ll find the 20 Treasury (Schatzkammer) and the Imperial Music Chapel (Hofmusikkapelle), where the Boys’ Choir sings Mass. Ever since Joseph Hayden and Franz Schubert were choirboys here, visitors have gathered like groupies on Sundays to hear the famed choir sing.

Returning to the bigger In der Burg courtyard, face Franz and turn left, passing through the tunnel, with a few tourist shops and restaurants, to spill out into spacious 21 Heldenplatz (Heroes’ Square). On the left is the impressive curved facade of the New Palace (Neue Burg). This vast wing was built in the early 1900s to be the new Habsburg living quarters (and was meant to have a matching building facing it). But in 1914, the heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand—while waiting politely for his long-lived uncle, Emperor Franz Josef, to die—was assassinated in Sarajevo. The archduke’s death sparked World War I and the eventual end of eight centuries of Habsburg rule.

Today the building houses the New Palace museums, an eclectic collection of weaponry, suits of armor, musical instruments, and ancient Greek statues. The two equestrian statues depict Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663-1736), who battled the Ottoman Turks, and Archduke Charles (1771-1847), who battled Napoleon. Eugene gazes toward the far distance at the prickly spires of Vienna’s City Hall.

Spin Tour: Make a slow 360-degree turn, and imagine this huge square filled with people.

In 1938, 300,000 Viennese gathered here, entirely filling vast Heroes’ Square, to welcome Adolf Hitler and celebrate their annexation with Germany—the “Anschluss.” The Nazi tyrant stood on the balcony of the New Palace and stated, “Before the face of German history, I declare my former homeland now a part of the Third Reich. One of the pearls of the Third Reich will be Vienna.” He never said "Austria," a word that was now forbidden.

When pondering why the Austrians—eyes teary with joy and vigorously waving their Nazi flags—so willingly accepted Hitler’s rule, it’s important to remember that Austria was already a fascist nation. Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, though pro-Catholic, pro-Habsburg, and anti-Hitler, was a fascist dictator who silenced any left-wing opposition. Also, memories of the grand Habsburg Empire were still fresh in the collective psyche. The once vast and mighty empire of 50 million at its 19th-century peak came out of World War I a tiny landlocked country of six million that now suffered terrible unemployment. The opportunistic Hitler promised jobs along with a return to greatness—and the Austrian people gobbled it up.

Standing here, it’s fascinating to consider Austrian aspirations for grandeur. In fact, the Habsburgs envisioned an ancient-Rome-inspired Imperial Forum stretching from here across the Ringstrasse.

• Walk on through the Greek-columned passageway (the Äusseres Burgtor), cross the Ringstrasse, and stand between the giant Kunsthistorisches and Natural History Museums, purpose-built in the 1880s to house the private art and scientific collections of the empire and to celebrate its culture and power. A huge statue of perhaps the greatest of the Habsburgs, Maria Theresa, stands in the center of it all.

Vienna’s biggest monument shows the empress holding a scroll from her father granting the right of a woman to inherit his throne. The statues and reliefs surrounding her speak volumes about her reign: Her four top generals sit on horseback while her four top advisors stand. Behind them, reliefs celebrate cultural leaders of her day, including little Wolfie Mozart with mentor “Papa” Joseph Haydn (with his hand on Mozart’s shoulder, facing the Natural History Museum). The moral of this propaganda: that a strong military and a wise ruler are prerequisites for a thriving culture—attributes that characterized the 40-year rule of the woman who was perhaps Austria’s greatest monarch.

• Our walk is finished. You’re in the heart of Viennese sightseeing. Surrounding this square are some of the city’s top museums. And the Hofburg Palace itself contains many of Vienna’s best sights and museums. From the opera to the Hofburg, from chocolate to churches, from St. Stephen’s to Sacher tortes—Vienna waits for you.

SIGHTSEEING PASSES AND COMBO-TICKETS

HOFBURG PALACE AND RELATED SIGHTS

▲▲▲Hofburg Imperial Apartments (Kaiserappartements)

▲▲▲Hofburg Treasury (Weltliche und Geistliche Schatzkammer)

▲▲Hofburg New Palace Museums (Sammlungen in der Neuen Burg)

▲Spanish Riding School (Spanische Hofreitschule)

▲Augustinian Church (Augustinerkirche)

State Hall (Prunksaal) of the Austrian National Library

Butterfly House (Schmetterlinghaus) in the Palace Garden (Burggarten)

Church Crypts near the Hofburg

▲▲Kaisergruft (Imperial Crypt)

▲St. Michael’s Church Crypt (Michaelerkirche)

▲▲▲St. Stephen’s Cathedral (Stephansdom)

▲▲▲Vienna State Opera (Wiener Staatsoper)

▲Dorotheum Auction House (Palais Dorotheum)

▲St. Peter’s Church (Peterskirche)

Jewish Museum Vienna (Jüdisches Museum Wien)

Austrian Postal Savings Bank (Österreichische Postsparkasse)

▲▲Natural History Museum (Naturhistorisches Museum)

▲Karlskirche (St. Charles Church)

▲Academy of Fine Arts Painting Gallery (Akademie der Bildenden Künste Gemäldegalerie)

▲▲Belvedere Palace (Schloss Belvedere)

▲Museum of Military History (Heeresgeschichtliches Museum)

Museum of Applied Arts (Museum für Angewandte Kunst, a.k.a. MAK)

▲Kunst Haus Wien Museum and Hundertwasserhaus

▲Imperial Furniture Collection (Hofmobiliendepot)

▲▲▲Schönbrunn Palace (Schloss Schönbrunn)

Schönbrunn Zoo (Tiergarten Schönbrunn)

▲Imperial Carriage Museum (Kaiserliche Wagenburg)

Vienna has a dizzying number of sights and museums, which cover the city’s rich culture and vivid history through everything from paintings to music to furniture to prancing horses. Just perusing the list on your TI-issued Vienna city map can be overwhelming. To get you started, I've selected the sights that are most essential, rewarding, and user-friendly, and arranged them by neighborhood for handy sightseeing.

Passes and combo-tickets (described below) can save a few euros. Bring cash, as some sights don’t take credit cards.

Avid sightseers should consider a pass or combo-ticket, which not only can save you money, but also time waiting in ticket lines. Note that those under 19 get in free to state-run museums and sights.

Passes: The Vienna Pass includes entry to the city’s top 60 sights and unlimited access to Vienna Sightseeing’s hop-on, hop-off tour buses (€60/1 day, €75/2 days, €90/3 days; purchase at TIs and several other locations around town—check at www.viennapass.com). It also lets you skip lines and step right up to the turnstile.

The much-promoted €25 Vienna Card (www.wienkarte.at) is not worth the mental overhead for most travelers. It gives you a 72-hour transit pass and minor discounts at the city’s museums.

Combo-Tickets: The €29 Sisi Ticket covers the Hofburg Imperial Apartments (with its Sisi Museum and Porcelain Collection), Schönbrunn Palace’s Grand Tour, and the Imperial Furniture Collection. At Schönbrunn, the ticket lets you enter the palace immediately, without a reserved entry time.

If you're seeing the Treasury (royal regalia and crown jewels) and the Kunsthistorisches (world-class art collection), the €20 combo-ticket is well worth it—and you get the New Palace museums as well (armory, old musical instruments, and statues from Ephesus).

The Haus der Musik (mod museum with interactive exhibits) has a combo deal with Mozarthaus Vienna (exhibits and artifacts about the great composer) for €18—saving a few euros for music lovers (though the Mozarthaus will likely disappoint all but the most die-hard Mozart fans).

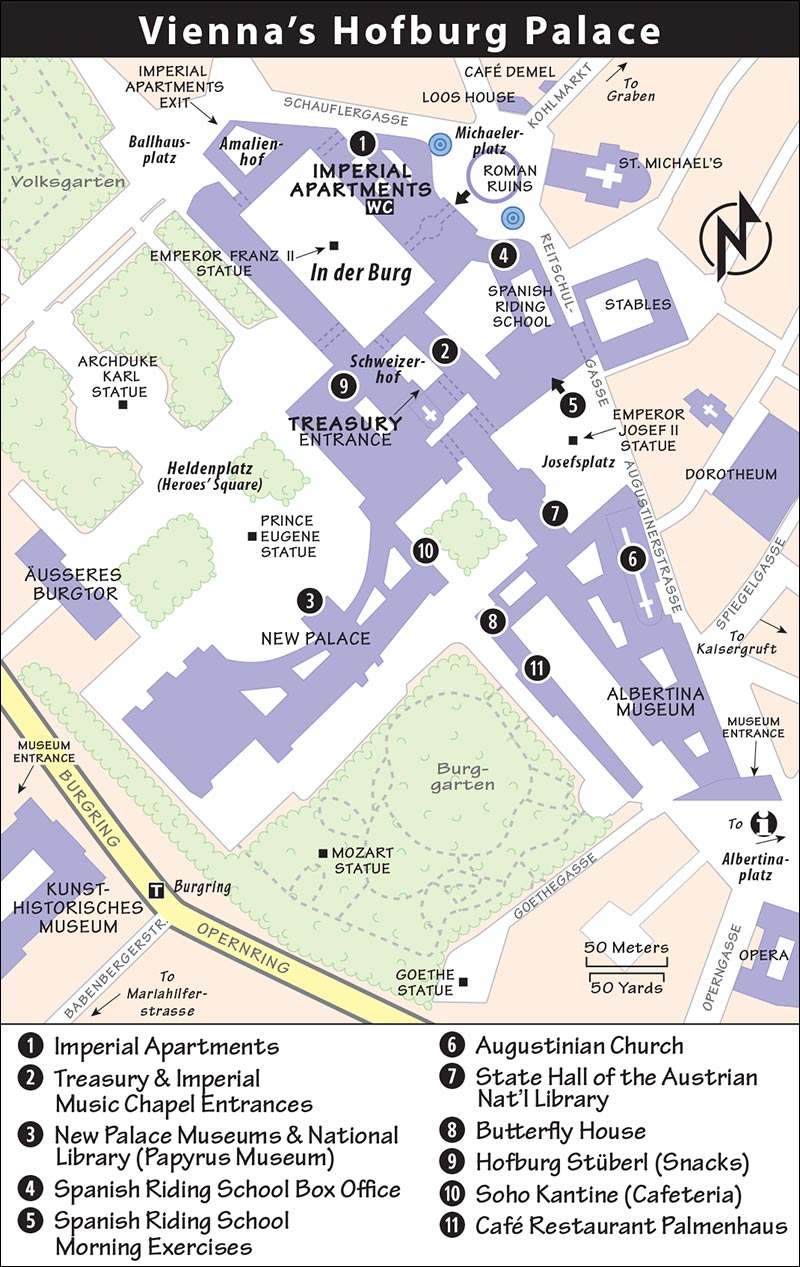

(See “Vienna’s Hofburg Palace” map, here.)

The imposing Imperial Palace, with 640 years of architecture, demands your attention. This first Habsburg residence grew with the family empire from the 13th century until 1913, when the last “new wing” opened. The winter residence of the Habsburg rulers until 1918, the Hofburg is still home to the Austrian president’s office, 5,000 government workers, and several important museums.

Don’t get confused by the Hofburg’s myriad courtyards and many museums. Focus on three sights: the Imperial Apartments, the Treasury, and the museums at the New Palace (Neue Burg). With more time, consider the Hofburg’s many other sights, covering various facets of the imperial lifestyle.

Eating at the Hofburg: Down the tunnel between the In der Burg courtyard and Heldenplatz is the tiny but handy $ Hofburg Stüberl sandwich bar—ideal for a cool, quiet sit and a drink or snack (open daily). The recommended Soho Kantine, off the Burggarten near the butterfly house, is also a cheap and practical option (see here).

These lavish, Versailles-type, “wish-I-were-God” royal rooms are the downtown version of the suburban Schönbrunn Palace. Palace visits are a one-way romp through three sections: a porcelain and silver collection, a museum dedicated to the enigmatic and troubled Empress Sisi, and the luxurious apartments themselves.

The Imperial Apartments are a mix of Old World luxury and modern 19th-century conveniences. Here, Emperor Franz Josef I lived and worked along with his wife Elisabeth, known as Sisi. The Sisi Museum traces the development of her legend, analyzing her fabulous but tragic life as a 19th-century Princess Diana. You’ll read bits of her poetic writing, see exact copies of her now-lost jewelry, and learn about her escapes, dieting mania, and chocolate bills.

Cost and Hours: €14, includes well-done audioguide; covered by Sisi Ticket; daily 9:00-17:30, July-Aug until 18:00, last entry one hour before closing; enter from under rotunda just off Michaelerplatz, through Michaelertor gate; tel. 01/533-7570, www.hofburg-wien.at.

Overview: Your ticket grants you admission to three separate exhibits, which you’ll visit on a pretty straightforward one-way route. The first floor holds a collection of precious porcelain and silver knickknacks (Silberkammer). You then go upstairs to the Sisi Museum, which has displays about her life. This leads into the 20 or so rooms of the Imperial Apartments (Kaiserappartements), starting in Franz Josef’s rooms, then heading into the dozen rooms where his wife Sisi lived.

If you listen to the entire audioguide, allow 40 minutes for the porcelain and silver collection, 30 minutes for the Sisi Museum, and 40 minutes for the apartments.

Visiting the Imperial Apartments: Your visit (and the excellent audioguide) starts on the ground floor.

Imperial Porcelain and Silver Collection: Browse the collection to gawk at the opulence and to take in some colorful Habsburg trivia. (Who’d have thunk that the court had an official way to fold a napkin—and that the technique remains a closely guarded secret?) Still, I wouldn't bog down here, as there's much more to see upstairs.

Once you’re through all those rooms of dishes, climb the stairs—the same staircase used by the emperors and empresses who lived here. At the top is a timeline of Sisi’s life. Swipe your ticket to pass through the turnstile, and enter the room with the model of the Hofburg. Circle to the far side to find where you’re standing right now, near the smallest of the Hofburg’s three domes. That small dome tops the entrance to the Hofburg from Michaelerplatz.

To the left of the dome (as you face the facade) is the steeple of the Augustinian Church. It was there, in 1854, that Franz Josef married 16-year-old Elisabeth of Bavaria, and their story began.

Sisi Museum: Empress Elisabeth (1837-1898)—a.k.a. “Sisi” (SEE-see)—was Franz Josef’s mysterious, beautiful, and narcissistic wife. This museum traces her fabulous but tragic life. The exhibit starts with Sisi’s sad end, showing her death mask, photos of her funeral procession (by the Hercules statues facing Michaelerplatz), and an engraving of a grieving Franz Josef. It was at her death that the obscure, private empress’ legend began to grow.

Sisi was nearly 5'8" (a head taller than her husband), had a 20-inch waist (she wore very tight corsets), and weighed only about 100 pounds. (Her waistline eventually grew...to 21 inches. That was at age 50, after giving birth to four children.) A statue, a copy of one of 30 statues that were erected in her honor in European cities, shows her holding one of her trademark fans. It doesn’t show off her magnificent hair, however, which reached down as far as her ankles in her youth.

Imperial Apartments: These were the private apartments and public meeting rooms for the emperor and empress.

Franz Josef’s apartments illustrate the lifestyle of the last great Habsburg ruler. In these rooms, he met with advisors and welcomed foreign dignitaries; hosted lavish, white-gloved balls and stuffy formal dinners; and raised three children. He slept (alone) on his austere bed while his beloved wife Sisi retreated to her own rooms. He suffered through the execution of his brother, the suicide of his son and heir, the murder of his wife, and the assassination of his nephew, Archduke Ferdinand, which sparked World War I and spelled the end of the Habsburg monarchy.

Among the rooms you’ll see is the audience room where Franz Josef received commoners from around the empire. Imagine you’ve traveled for days to have your say before the emperor. You’re wearing your new fancy suit—Franz Josef required that men coming before him wear a tailcoat, women a black gown with a train. He’d stand at the lectern (far left) as the visiting commoners had their say (but for no more than two and a half minutes). On the lectern is a partial list of 56 appointments he had on January 3, 1910 (three columns: family name, meeting topic, and Anmerkung—the emperor’s “action log”).

Franz Josef’s study evokes how seriously the emperor took his responsibilities as the top official of a vast empire. Famously energetic, Franz Josef lived a spartan life dedicated to duty; in his bedroom, notice his no-frills iron bed. He typically rose before dawn and started his day in prayer, kneeling at the prayer stool against the far wall. While he had a typical emperor’s share of mistresses, his dresser was always well-stocked with photos of Sisi.

In Sisi’s bedroom, refurbished in the Neo-Rococo style in 1854, there’s a red carpet, covered with oriental rugs. The room always had lots of fresh flowers. Sisi not only slept here, but also lived here—the bed was rolled in and out daily—until her death in 1898. The desk is where she sat and wrote her letters and sad poems. In her dressing/exercise room, servants worked three hours a day on Sisi’s famous hair. She’d exercise on the wooden structure and on the rings suspended from the doorway to the left. Afterward, she’d get a massage on the red-covered bed.

In the small salon, notice the portrait of Crown Prince Rudolf, Franz Josef’s and Sisi’s only son. On the morning of January 30, 1889, the 30-year-old Rudolf and a beautiful baroness were found shot dead in an apparent murder-suicide in his hunting lodge in Mayerling. The scandal shocked the empire and tainted the Habsburgs; Sisi retreated further into her fantasy world, and Franz Josef carried on stoically with a broken heart.

The tour ends in the dining room. It’s dinnertime, and Franz Josef has called his extended family together. The settings are modest...just silver. Gold was saved for formal state dinners. Next to each name card was a menu listing the chef responsible for each dish. (Talk about pressure.) Franz Josef enforced strict protocol at mealtime: No one could speak without being spoken to by the emperor, and no one could eat after he was done. While the rest of Europe was growing democracy and expanding personal freedoms, the Habsburgs preserved their ossified worldview to the bitter end.

In 1918, World War I ended, Austria was created as a modern nation-state, the Habsburgs were tossed out...and Hofburg Palace was destined to become a museum.

One of the world’s most stunning collections of royal regalia, the Hofburg Treasury shows off sparkling crowns, jewels, gowns, and assorted Habsburg bling in 21 darkened rooms. The treasures, well explained by an audioguide, include the crown of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne’s saber, a unicorn horn, and more precious gems than you can shake a scepter at.

Cost and Hours: €12, €20 combo-ticket with Kunsthistorisches and New Palace museums; Wed-Mon 9:00-17:30, closed Tue; audioguide-€4 or €7/2 people, guided tours daily at 14:00 (€3); from the Hofburg’s central courtyard pass through the black, red, and gold gate, then follow Schatzkammer signs to the Schweizerhof; tel. 01/525-240, www.kaiserliche-schatzkammer.at.

Visiting the Treasury: The Habsburgs saw themselves as the successors to the ancient Roman emperors, and they wanted crowns and royal regalia to match the pomp of the ancients. They used these precious objects for coronation ceremonies, official ribbon-cutting events, and their own personal pleasure. You’ll see the prestigious crowns and accoutrements of the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire (a medieval alliance of Germanic kingdoms so named because it wanted to be considered the continuation of the Roman Empire).

Here’s a rundown of the highlights (the audioguide is much more complete).

Room 2: The personal crown of Rudolf II (1602) occupies the center of the room along with its accompanying scepter and orb; a bust of Rudolf II (1552-1612) sits nearby. The crown’s design symbolically merges a bishop’s miter (“Holy”), the arch across the top of a Roman emperor’s helmet (“Roman”), and the typical medieval king’s crown (“Emperor”).

Two centuries later (1806), this crown and scepter became the official regalia of Austria’s rulers, as seen in the large portrait of Franz I (the open-legged guy behind you). Napoleon Bonaparte had just conquered Austria and dissolved the Holy Roman Empire. Franz (r. 1792-1835) was allowed to remain in power, but he had to downgrade his title from “Franz II, Holy Roman Emperor” to “Franz I, Emperor of Austria.”

Rooms 3 and 4: These rooms contain some of the coronation vestments and regalia needed for the new Austrian (not Holy Roman) Emperor. There was a different one for each of the emperor’s subsidiary titles, e.g., King of Hungary or King of Lombardy. So many crowns and kingdoms in the Habsburgs’ vast empire!

Room 5: Ponder the Cradle of the King of Rome, once occupied by Napoleon’s son, who was born in 1811 and made King of Rome. While pledging allegiance to democracy, Napoleon in fact crowned himself Emperor of France and hobnobbed with Europe’s royalty. When his wife Josephine could not bear him a male heir, Napoleon divorced her and married into the Habsburg family.

Room 6: For Divine Right kings, even child-rearing was a sacred ritual that needed elaborate regalia for public ceremonies. The 23-pound gold basin and pitcher were used to baptize noble children, who were dressed in the baptismal dresses displayed nearby.

Room 7: These jewels are the true “treasures,” a cabinet of wonders used by Habsburgs to impress their relatives (or to hock when funds got low).

Religious Rooms: Several rooms hold religious objects—crucifixes, chalices, mini-altarpieces, reliquaries, and bishops’ vestments. Like the medieval kings who preceded them, Habsburg rulers mixed the institutions of church and state, so these precious religious accoutrements were also part of their display of secular power.

Regalia of the Holy Roman Empire: The next few rooms (11 and 12) contain some of the oldest and most venerated objects in the Treasury—the robes, crowns, and sacred objects of the Holy Roman Emperor.

The big red-silk and gold-thread mantle, nearly 900 years old, was worn by Holy Roman Emperors at their coronations. The collection’s highlight is the 10th-century crown of the Holy Roman Emperor. It was probably made for Otto I (c. 960), the first king to call himself Holy Roman Emperor. The Imperial Crown swirls with symbolism “proving” that the emperor was both holy and Roman: The cross on top says the HRE ruled as Christ’s representative on earth, and the jeweled arch over the top is reminiscent of the parade helmet of ancient Romans. The jewels themselves allude to the wearer’s kinghood in the here and now. Imagine the impression this priceless, glittering crown must have made on the emperor’s medieval subjects.

Nearby is the 11th-century Imperial Cross that preceded the emperor in ceremonies. Encrusted with jewels, it had a hollow compartment (its core is wood) that carried substantial chunks thought to be from the cross on which Jesus was crucified and the Holy Lance used to pierce his side (both pieces are displayed in the same glass case). Holy Roman Emperors actually carried the lance into battle in the 10th century. Look behind the cross to see how it was a box that could be clipped open and shut, used for holding holy relics. You can see bits of the “true cross” anywhere, but this is a prime piece—with the actual nail hole.

Another case has additional objects used in the coronation ceremony: The orb (orbs were modeled on late-Roman ceremonial objects, then topped with the cross) and scepter (the one with the oak leaves) were carried ahead of the emperor in the procession.

Now picture all this regalia used together. The painting (Room 12) shows the coronation of Maria Theresa’s son Josef II as Holy Roman Emperor in 1764. Set in a church in Frankfurt (filled with the bigwigs—literally—of the day), Josef is wearing the same crown and royal garb that you’ve just seen.

The New Palace (Neue Burg) houses three separate collections—an armory (with a killer collection of medieval weapons), historical musical instruments, and classical statuary from ancient Ephesus. Renting the audioguide brings the exhibits to life and lets you hear the collection’s fascinating old instruments being played. An added bonus is the chance to wander alone, with almost no tourists, among the royal Habsburg halls, stairways, and painted ceilings.

Cost and Hours: €15 ticket covers all three collections and the Kunsthistorisches Museum across the Ring, €20 combo-ticket adds the Hofburg Treasury, Wed-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon-Tue, audioguide-€3, tel. 01/525-240, www.khm.at.

This stately 300-year-old Baroque hall at the Hofburg Palace is the home of the renowned Lipizzaner stallions. The magnificent building was an impressive expanse in its day. Built without central pillars, it offers clear views of the prancing horses under lavish chandeliers, with a grand statue of Emperor Charles VI on horseback at the head of the hall.

Lipizzaner stallions are known for their noble gait and Baroque profile. These regal horses have changed shape with the tenor of the times: They were bred strong and stout during wars, and frilly and slender in more cultured eras. But they’re always born black, fade to gray, and turn a distinctive white in adulthood.

Seeing the Horses and Buying Tickets: The school offers three ways to see the horses—performances, morning exercises, and guided tours of the stables (check the events list on the school’s website at www.srs.at; enter your dates under “Event Search”). You can purchase tickets online or at the box office (opens at 9:00, located inside the Hofburg—go through the main Hofburg entryway from Michaelerplatz, then turn left into the first passage, tel. 01/533-9031). Photos are not allowed at any events, nor are children under age 3.

To see the horses for free, you can just walk by the stables at any time of day when the horses are in town. From the covered passageway along Reitschulgasse, there’s a big window from where you can usually see the horses poking their heads out of their stalls.

Performances: The Lipizzaner stallions put on great 80-minute performances featuring choreographed moves to jaunty recorded Viennese classical music. The pricey seats book up months in advance, but standing room is usually available the same day (seats about €50-160, standing room about €25, prices vary depending on the show; Feb-mid-June and mid-Aug-Dec usually Sat-Sun at 11:00, no shows Jan and mid-June-mid-Aug). If buying tickets online, look for the tiny English flag at the top of the page when you're redirected to the ticket purchase page.

Morning Exercises: For a less expensive, more casual experience, morning exercises with music take place on weekday mornings in the same hall and are open to the public. Don’t have high expectations, as the horses often do little more than trot and warm up. Tourists line up early at Josefsplatz (the large courtyard between Michaelerplatz and Albertinaplatz), at the door marked Spanische Hofreitschule. But there’s no need to show up when the doors open at 10:00, since tickets never really “sell out” (€15, available at the door in high season—otherwise buy at visitors center on Michaelerplatz, family discounts, generally Tue-Fri 10:00-12:00, occasionally also on Mon, no exercises mid-June-July).

Guided Tours: One-hour guided tours in English are given almost every afternoon year-round. You'll see the Winter Riding School with its grand Baroque architecture, the Summer Riding School in a shady courtyard, and the stables (€18; tours usually daily at 14:00, 15:00, and 16:00; reserve ahead by emailing office@srs.at or calling the box office).

Built into the Hofburg, this is the Gothic and Neo-Gothic church where the Habsburgs got latched and dispatched (married and buried). Today, the royal hearts are in the church vault.

Cost and Hours: Church—free, open long hours daily; vault—€2.50 suggested donation, open to the public after Sunday Mass (at about 12:45), at Augustinerstrasse 3, facing Josefsplatz.

Visiting the Church: In the front (above the altar on the right), notice the windows, from which royals witnessed the Mass in private. Don’t miss the exquisite, pyramid-shaped memorial (by the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova) to Maria Theresa’s favorite daughter, Maria Christina. The hearts of 54 Habsburg nobles are in urns in a vault off the church’s Loreto Chapel (on the right beyond the Maria Christina memorial).

The church’s 11:00 Sunday Mass is a hit with music lovers. It’s both a Mass and a concert, often with an orchestra accompanying the choir (acoustics are best in front). Pay by contributing to the offering plate and buying a CD afterward. Check posters by the entry or www.hochamt.at to see what’s on—typically you’ll hear one of Mozart or Haydn’s many short Masses.

The National Library (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek) runs several museums in different parts of the Hofburg complex. The most worthwhile is the State Hall (Prunksaal), a postcard-perfect Baroque library entered from Josefplatz, next to the Augustinian Church (see map on here). In this former imperial library, with a statue of Charles VI in the center, you’ll find yourself whispering. The setting takes you back to 1730 and gives you the sense that, in imperial times, knowledge of the world was for the elite—and with that knowledge, the elite had power. More than 200,000 old books line the walls, but patrons go elsewhere to read them—the hall is just for show these days.

Cost and Hours: €7, daily 10:00-18:00, Thu until 21:00, tel. 01/53410, www.onb.ac.at.

The Burggarten greenbelt, once the backyard of the Hofburg and now a people’s park, welcomes visitors to loiter on the grass. The iron-and-glass pavilion (c. 1910 with playful Art Nouveau touches) now houses the recommended Café Restaurant Palmenhaus and a small, fluttery butterfly exhibit.

Cost and Hours: €6.50; April-Oct daily 10:00-16:45, Sat-Sun until 18:15; Nov-March daily 10:00-15:45, www.schmetterlinghaus.at.

This impressive museum has three highlights: the imposing state rooms of the former palace, noteworthy collections of classic modernist paintings and European graphic arts, and excellent temporary exhibits.

The building, at the southern tip of the Hofburg complex (near the opera), was the residence of Maria Theresa’s favorite daughter, Maria Christina, who was allowed to marry for love rather than political strategy. Her many sisters were jealous. (Marie-Antoinette had to marry the French king...and lost her head over it.) Maria Christina’s husband, Albert of Saxony, was a great collector of original drawings and prints, which he amassed to cover all the important art movements from the late Middle Ages until the early 19th century (including prized works by Dürer, Rembrandt, and Rubens). As it’s Albert and Christina’s gallery, it’s charmingly called the “Albertina.”

Cost and Hours: €13, daily 10:00-18:00, Wed until 21:00, helpful audioguide-€4, overlooking Albertinaplatz across from the TI and opera, tel. 01/534-830, www.albertina.at.

Visiting the Museum: The entry level often houses photography exhibits. Climbing the stairs you reach the main attractions: the state rooms (Prunkräume) on your left on level 1, and the Batliner Collection on your right on level 2. Excellent special exhibitions, often featuring works from the Albertina’s collections, are shown on level 2 and in the basement galleries.

State Rooms (level 1): Wander freely under chandeliers and across parquet floors through a handful of rooms of imperial splendor, unconstrained by velvet ropes. Many rooms are often closed for special functions, but even a few rooms give a good look at imperial Classicism—this is the only post-Rococo palace in the Habsburg realm.

Batliner Collection (level 2): This manageable collection sweeps you quickly through modern art history, featuring minor works by major artists (such as Monet, Degas, Munch, Klimt, Matisse, Kirchner, Nolde, and Bacon). Though the collection is permanent, what's on display rotates through about 100 works selected from the 300 in the archives.

Two churches near the Hofburg offer starkly different looks at dearly departed Viennese: the Habsburg coffins in the Kaisergruft and the commoners’ graves in St. Michael’s Church.

Visiting the imperial remains of the Habsburg family is not as easy as you might imagine. These original organ donors left their bodies—about 150 in all—in the unassuming Kaisergruft, their hearts in the Augustinian Church (viewable Sun after Mass), and their entrails in the crypt below St. Stephen’s Cathedral. Don’t tripe.

Cost and Hours: €5.50, daily 10:00-18:00, €0.50 map includes Habsburg family tree and a chart locating each coffin, crypt is in the Capuchin Church at Tegetthoffstrasse 2 at Neuer Markt; tel. 01/512-6853.

Visiting the Kaisergruft: Descend into a low-ceilinged crypt full of gray metal tombs. Start up the path, through tombs ranging from simple caskets to increasingly big monuments with elaborate metalwork ornamentation.

You soon reach the massive pewter tomb of Maria Theresa under the dome. The only female Habsburg monarch, she had to be granted special dispensation to rule. Her 40-year reign was enlightened and progressive. She and her husband, Franz I, recline Etruscan-style atop their fancy coffin, gazing into each other's eyes as a cherub crowns them with glory. They were famously in love (though Franz was less than faithful), and their numerous children were married off to Europe's royal houses. Maria Theresa outlived her husband by 15 years, which she spent in mourning. Old and fat, she installed a special lift to transport herself down into the Kaisergruft to visit her dear, departed Franz. At the four corners of the tomb are the Habsburgs' four crowns: the Holy Roman Empire, Hungary, Bohemia, and Jerusalem. At his parents’ feet lies Josef II, the patron of Mozart and Beethoven. Compare the Rococo splendor of Maria Theresa’s tomb with the simple coffin of Josef, who was known for his down-to-earth ruling style during the Age of Enlightenment.

Head on through the next room, and then down three steps, to a room illustrating the Habsburgs' fading 19th-century glory. There's the appropriately austere military tomb of the long-reigning Franz Josef (see sidebar on here). Alongside is his wife, Elisabeth—a.k.a. Sisi (see here)—who always wins the "Most Flowers" award. Their son was Crown Prince Rudolf. Rudolf and his teenage mistress supposedly committed suicide together in 1889 at Mayerling hunting lodge...or was it murder? It took considerable ecclesiastical hair-splitting to win Rudolf this hallowed burial spot.

In the final room (with humbler copper tombs), you reach the final Habsburgs. Karl I (see his bust, not a tomb), the last of the Habsburg rulers, was deposed in 1918. His sons Crown Prince Otto and Archduke Karl Ludwig are entombed near their mother, Zita.

Today there are about 700 living Habsburg royals, mostly in exile. When they die, they will be buried in their countries of exile, not here.

St. Michael’s Church, which faces the Hofburg on Michaelerplatz, offers a striking contrast to the imperial crypt. Regular tours take visitors underground to see a typical church crypt, filled with the rotting wooden coffins of well-to-do commoners.

Cost and Hours: €7 for 45-minute tour, Mon-Sat at 11:00 and 13:00, no tours Sun, mostly in German but with enough English, wait at church entrance at the sign advertising the tour and pay the guide directly, mobile 0650-533-8003, www.michaelerkirche.at.

Visiting the Crypt: Climbing below the church, you’ll see about a hundred 18th-century coffins and stand on three feet of debris, surrounded by niches filled with stacked lumber from decayed coffins and countless bones. You’ll meet a 1769 mummy in lederhosen and a wig, along with a woman who is clutching a cross and has flowers painted on her high heels. You’ll learn about death in those times, including how the wealthy—not wanting to end up in standard shallow graves—instead paid to be laid to rest below the church, and how, in 1780, Emperor Josef II ended the practice of cemetery burials in cities but allowed the rich to become the stinking rich in crypts under churches.

This massive Gothic church with the skyscraping spire sits at the center of Vienna. Its highlights are the impressive exterior, the view from the top of the south tower, a carved pulpit, and a handful of quirky sights associated with Mozart and the Habsburg rulers.

Cost and Hours: Church foyer and north aisle—free, daily 6:00-22:00 (from 7:00 on Sun); main nave—€4.50, Mon-Sat 9:00-11:30 & 13:00-16:30, Sun 13:00-16:30, June-Aug until 18:30; audioguide-€1; south and north towers, catacombs, and treasury have varying costs and hours—see below; English Mass each Sat at 19:00, tel. 01/515-523-526, www.stephanskirche.at.

Tours: The €5.50 tours in English are entertaining (daily at 10:30, check information board inside entry to confirm schedule; price includes main nave entry, minimum 5 people). The €1 audioguide is helpful.

Download my free St. Stephen’s Cathedral audio tour.

Download my free St. Stephen’s Cathedral audio tour.

Treasury: Consider riding the elevator (just inside the cathedral’s entry) to the treasury, with precious relics, dazzling church art, a portrait of Rudolf IV (considered the earliest German portrait), and wonderful views down on the nave (€5.50 admission includes audioguide, daily 9:00-16:30, July-Aug until 17:30).