Chapter 14

Habit 8 – accepting that ‘no’ means ‘no’!

It’s inevitable that we will all have times when we don’t want to accept ‘no’ for an answer. This usually results in a Chimp hijack. As adults, we learn to programme our Computers to deal with this. Children need help to programme their Computer in order to manage disappointment.

•Helping to programme the child’s Computer

•Helpful beliefs

•An action plan

•Overreacting

•Seeing the child beyond the Chimp

Helping to programme the child’s Computer

It is natural and healthy for a child, or an adult, to react when they can’t have what they want or when things don’t go the way that they want them to. However, reacting isn’t usually helpful.

By going back to basics, we can see how to minimise the child’s reaction and also how to avoid the conflict that can result from a child not getting their own way.

The child’s mind works the same as the adult’s. Therefore, the first reaction we expect to see will be from the Chimp. To move forward, we need to not engage with the Chimp but to rely on the child having a well-programmed Computer.

Important point

The Computer must be programmed before the event.

Let’s start with two scenarios:

Carl and bedtime

Carl knows that his bedtime is at 8 p.m. However, every night he tries to stay up for longer. Every night there is the same battle. Sometimes, because he has behaved well and it’s the weekend, he is allowed to stay up until 8.30 or 9.00 p.m. The bedtime battle is driving his parent up the wall. The parent can’t understand why Carl just can’t accept the rules and go to bed peacefully. When Carl is confronted, he just rolls around the floor and the parent’s Chimp takes over.

Denise and the tattoo

Denise is angry and upset with her parents because they will not let her get a tattoo. Two of her friends have got tattoos on their ankles and she feels it is unfair that her parents are being unreasonable. Denise cannot take ‘no’ for an answer and brings up the topic regularly. Her inability to accept ‘no’ is causing stress to her parents.

Helpful beliefs

As a starting point, we could ask what beliefs we want to establish, that will help a child to accept that sometimes ‘no’ really does mean ‘no’?

If we consider how most adults programme their own Computer to accept that things might not go their way, then this will give us some ideas. There are several beliefs that might be in the adult’s Computer that could stop the adult’s Chimp in its tracks. Here are some possible examples:

•Life is not always fair

•Sometimes we have to accept that we can’t have what we want

•Sometimes we have to be patient and wait for something

•Complaining and getting upset doesn’t help

•Accepting the unchangeable is sensible

•Working with a fixed situation is better than being frustrated by it

•Moving on to something else is helpful

•Having a plan to deal with disappointment makes things easier

Imagine you are trying to deal with a situation in which you can’t have your own way. What beliefs are you holding that would help you to deal with the situation and get over it? Could you share these with your child?

If you act as a role model to show how you also have to manage yourself when you can’t have what you want, the child might copy your behaviour.

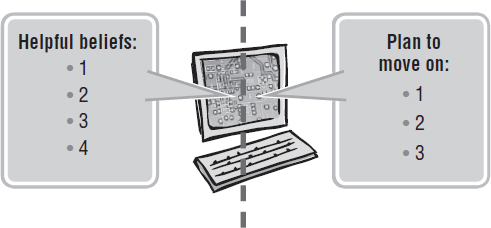

An action plan

Having helpful beliefs in the Computer will settle the Chimp down. However, if we don’t have a plan to move forward, it is very likely the Chimp will still come back complaining. This is why, when Carl’s parent confronted him, Carl didn’t have a plan and so began to roll about on the floor. By helping the child to appreciate that we need to have a plan to move on, they can learn this as a habit for life.

Therefore, there are two ways to help the child to accept what they feel is unacceptable:

•Programme the Computer with helpful beliefs

•Programme the Computer with a plan to move on – an action plan

Important point

Having an action plan ready to deal with any disappointment or frustration is very constructive and can save hours of agitation!

The stages of an action plan

Here is a suggested action plan for when a disappointment takes place and the child has to accept that ‘no’ really does mean ‘no’.

Step 1

Accept that disappointment or frustration is a very healthy and normal reaction.

It would help to discuss this with your child and to help them to appreciate that healthy reactions are sometimes unhelpful. However, accepting that it is normal to feel this way, such as being angry, frustrated or sad, can be reassuring and remove any possible guilt.

Step 2

Express any emotional reaction and feelings constructively.

Learning to express disappointment with the right words can prevent someone from expressing their disappointment inappropriately. So even a simple and obvious expression such as ‘This really disappoints me’ can help to release the emotional pressure valve! It’s important to choose the ‘right’ words, because saying something like, ‘This makes me really angry’, might only make matters worse. Using very emotional words can cause our emotions to become stronger.[1]

Important point

It is helpful for the child to use the right words to express themselves; for example, saying I am ‘disappointed’ is usually better than saying I am ‘angry’.

Step 3

Form a plan for going forward.

Any difficult situation that doesn’t seem to have a way forward is likely to be a source of trouble. It is important to find a way forward whenever a problem arises. Seeing a way forward with a plan helps us all to move on. For example, putting a new challenge in place could be a way to get over a ‘failure’. Another example would be to use a distraction, such as a pleasurable activity to effectively change the focus of the child.

We can now review the two scenarios from the start of this chapter to see these steps in action.

Carl and bedtime reviewed

One possible reason for a collision between parents and children is because they do not have the same understanding of a situation when starting a conversation. So in this example, we could ask the parent what is in their mind when they ask Carl to go to bed at eight?

The answer could be that Carl becomes very tired and grumpy if he doesn’t get his sleep, or there might be many other reasons why his parent wants him to go to bed at eight: Does Carl understand the benefits to him if he goes to bed at eight, or the consequences if he stays up beyond eight? Sometimes discussing with a child the reasoning behind a ‘no means no’ answer can help immensely. However, this has to be done BEFORE the event occurs, because once the battle is on, Carl will remain in Chimp mode and is not likely to be able to listen, reason or discuss. Therefore, if you were going to try and reason with Carl, it would need to be done when he is in a sensible and receptive mode, well before bedtime. If you can talk through the benefits of going to bed and the consequences of him staying up, then he might register these in his Computer when it comes to bedtime.

If the actual act of going to bed has no positives, why would we expect Carl to want to comply? Is it possible that getting into bed could have its own rewards? This would then be the plan to move him away from the desire to stay up. Examples include:

•Some children willingly go to bed if there is a bedtime story. There is evidence that this also helps them to sleep bettert[2]

•Others will go if they are given a star on a star chart for getting to bed on time. This can then be traded in for a reward each week

•Some children love to talk through their day, and bedtime is an ideal way to end the day and plan the next day. This special, sacrosanct time can make for good parent-child bonding

Important point

If a child can discuss and have ownership of the ‘rules’ of bedtime, then they are much more likely to comply with them.

What about the concession of staying up late on Saturday nights? As long as this is discussed with reasoning beforehand, most children will appreciate the different bedtime from a weeknight.

There is a danger! Remember the ‘variable success’ principle from Chapter 4. If we have intermittent reinforcement then we can strengthen unwanted behaviours. What this means is that, if we are inconsistent and give way at times, the behaviour we don’t want is likely to become stronger. So, let’s say Carl has been good and we allow him to stay up late during the week. Carl has been taught that there is always a possibility that he could stay up late, if he can convince us. Therefore, he will always keep trying and pleading because he has discovered that there are exceptions. The important point is to be consistent with the bedtime both during the week and at weekends.

Important point

Try to be consistent in your approach. Inconsistent approaches will encourage the child to challenge you.

Denise and the tattoo reviewed

This scenario is typical of many situations where a parent is making a decision that is based on an opinion. These parents don’t feel it is right for a young person to have a tattoo; other parents might disagree. In order to try and resolve the conflict, it could help to go through the steps outlined above.

First the parents could express an understanding of the emotions that Denise is feeling and agree that it is reasonable for her to have these emotions. This demonstration of understanding is often very helpful for the child.

The second step is to help her to express how she feels in a constructive way. Allowing her to speak and gather her thoughts will help her to release some of these emotions.

The third step, moving forward with a plan, is best done by discussion, where possible! Discussions about people regretting getting certain tattoos, or changing what tattoo they have, will probably fall on deaf ears. Rationality often fails with an emotionally distressed young person, so sometimes speaking about emotions instead can help. For example, expressing as a parent how much you don’t want her to make a mistake, and how much this would distress you, is more likely to be heard than logical reasons, letting her know that you might be making a mistake but you have to go with your feelings. Following emotional discussions, it is helpful to try and encourage rationalisation of the situation. Eventually, Denise will have the right to make her own decisions. Therefore, eventually, she might have the tattoo she wants. Offering a series of temporary tattoos in the meantime might help!

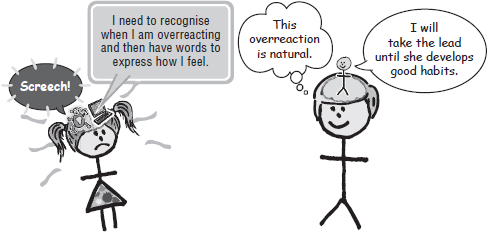

Overreacting

When a child can’t have what they want or becomes distressed, their Chimp usually overreacts to the situation. A child’s Chimp naturally overreacts. This part of the mind does not have the ability to gain a sense of perspective. Therefore it has a tendency to see everything catastrophically. Some adults who show this overreaction to setbacks have learnt this behaviour in childhood and repeat the behaviour throughout adult life, instead of stopping and reconsidering how their Chimp can be managed.

Important point

It is a very healthy Chimp that overreacts.

Managing the Chimp, and preventing overreactions from occurring, means turning to the Computer again. We can first programme the Computer to recognise when an overreaction is taking place. Then accept that the overreaction is happening and turn the emotions into words by expressing what that overreaction is about: this will help to clarify concerns and fears. Finally, we can bring some perspective into the picture by looking at what this situation will mean in a few hours, a few weeks or even a year’s time; this usually helps a lot. This is not an easy process for an adult to do, let alone a child. So it is fair to say that the adult will need to take the lead until the child develops the habit of checking any overreactions.

Some suggested steps to prevent an overreaction from persisting

•Learn to recognise that an overreaction is taking place

•Express in words what the overreaction is about

•Bring perspective by considering if the issue will be important in the future

Seeing the child beyond the Chimp

We have discussed in detail how the mind is a machine that can hijack you and have its own agenda. If you can view a lot of your child’s actions as being a hijack, then you might not only feel differently towards events but are also likely to respond differently. Within the model, we can see that the child will operate from the Chimp system for much of the time. So they are likely to be impulsive, not think through consequences and follow natural instincts. If you can see this happening and recognise that it is only the Chimp within the child hijacking them, then your approach can be modified. You could now join forces with the child to help them to recognise what is happening and then help them to manage their Chimp. The Human within the child will welcome this, just as adults who are hijacked also welcome support to manage their Chimp.

Example: the five-year-old’s temper tantrum

Joey has tried to win a game when playing on his iPad. He has failed and can’t accept this. He reacts by throwing the iPad at the floor and starts screaming.

Before we look at how you might want to manage this situation, let’s step back and see what the neuroscience of the mind is telling us is actually happening.

The Chimp within the child is likely to see failure in the game as catastrophic and it is likely to believe that others will perceive them as being stupid and a failure as a person. The Human within the child is disappointed at not winning and is most likely embarrassed by the reaction of the Chimp and doesn’t want to get into trouble. The Computer is very likely to be blank! The rules of the mind dictate that the Chimp is strongest and can only realistically be managed via the Computer. Therefore, with this situation the child is fated to act in a destructive way.

A way forward

We can pre-programme the Computer by discussing with the child what might happen if their Chimp gets out. As we have seen earlier, a simple way to do this is to practise with the child. Help them to have fun by role-playing a temper tantrum by their Chimp. By discussing how the child would like to react to a failure, the child will have ownership of the Computer’s plan to manage their Chimp.

For example, you and your child could come up with something like this for a Computer programme to manage failure:

•Let the Chimp express itself in a helpful way. This could be by letting the child tell you exactly how their Chimp is feeling. Alternatively, it could be more physical. For example, by letting their Chimp do something simple such as jump up and down five times. Some children will not be so energetic and might want to let their Chimp have a quiet rant. As we are all unique, only you and your child can establish what will work for both of you. It helps immensely if the child has ownership of the plan.

•Say sorry, if the Chimp has caused any problems by its actions.

•Try to put right any problems, if there are practical things that can be done. You might need to suggest to the child what could be done, such as pick up the iPad and place it somewhere safe.

•If possible and appropriate, encourage the child to have a laugh at their Chimp’s antics.

•Ask what they can learn from this? For example, this could be about perspective or about doing your best and accepting that things don’t always work out.

What we are effectively doing is giving the child a plan to work with that the Computer can put straight into action and make into a habit.

We could also put into the child’s Computer some truths and values that the Chimp will see when it turns to the Computer. You would have to decide what these truths are, as we all have different views. Here are some examples that you may or may not agree with:

•Games are about fun

•Enjoying the game is as important as winning

•The outcome of a game doesn’t define me

•People like good losers

•I can’t be good at everything

•Things don’t always go the way I want them to

•Humans get disappointed, but Chimps get angry or upset

These values and truths might need to be reinforced many times before the child can use them effectively. This principle is no different for adults. It’s worth sitting down with your child and working together on these beliefs or values for various situations.

Beliefs usually underpin a Chimp reaction. In this case, Joey’s Computer had been programmed by his Chimp to believe that, if you can’t win, everybody sees you as a failure. It can be very enlightening to see what beliefs a child holds, as these beliefs will often dictate their reaction or behaviours.

Summary

•Children need help to constructively programme their Computer

•To programme a Computer effectively it needs:

⚬Helpful beliefs

⚬An action plan

•Helping children to use the right words to express how they feel can diffuse unhelpful emotions

•Giving a child ownership of agreed behaviours makes them likelier to see them happen

•Try to be consistent in your approach and behaviours

•Try to see the child beyond the Chimp