Chapter 7

Boundaries and Systems

Boundaries don’t keep us apart,

they bring us together; they protect us

so we can be safe with another person,

a way of being with each other as equals

so that each stands in the light.

—Nancy Kline (1999)

In this dimension of the Self as Coach model, I’m going to artificially pull apart Boundaries and Systems so we can take a look at the nuances before we examine how these are on the same side of the coin.

The Necessity of Boundaries

What do you know about your own boundary preferences? How much physical space do you like to have around you—your personal space? How clear are you on what you say yes to and what you say no to? Is it harder to say yes or no to some people more than others? Do you make decisions by going inside and checking your own rudder or are you often influenced by what others would like?

These questions touch on the outer edges of where our individual boundaries start and stop, how crisp they are, or how much they absorb or hold at a distance the challenges and victories of others. This is where boundaries begin for us as coaches, as well. In this dimension, our ability to hold strong boundaries is intertwined with keeping our empathy balanced. If we absorb (empathy contagion) the experiences of others —taking them on, taking them home, wanting to rescue and alleviate—chances are, our boundaries are wobbly.

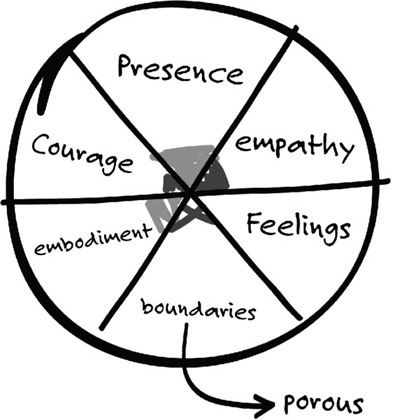

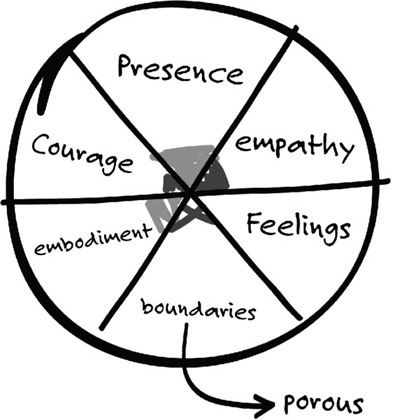

Consider the boundaries spectrum in Figure 7.1 and see where you might locate yourself today.

Figure 7.1 Boundaries

Limited boundaries restrict our work as coaches because when our boundaries are particularly porous we take on others’ issues. Alcoholics Anonymous has long used this helpful term for porous boundaries: collusion. This term describes the destructive power wherein there are no boundaries, only rescue and agreement in the face of false realities. Collusion is a helpful concept in coaching, as well. When we collude, we ensure no change will occur.

In coaching, when our boundaries are limited and porous, we have an almost automatic tendency to take on what our clients bring to us, to want to solve, to make others feel better, to save them from themselves, to put on the cape and go to work. Ultimately, we lose our coaching rudder and our effectiveness when we are at this end of the spectrum. Through the lens of Horney, this is the red zone wherein we are Moving Toward too much. Our work in coaching is to help our clients see their stories and assumptions, not to jump into their situation and become a part of it.

At the other end of the spectrum, when our boundaries are too rigid we run the risk of disconnecting. This links to insufficient empathy; it is Horney’s Moving Away stance taken too far and is likely accompanied by a limited range of feelings.

When our boundaries are agile, we are at our best; we are able to hear our client’s stories and observe patterns, and to hold a strong alliance while able to surface what we observe instead of getting swept into their situation or story.

My Inner Landscape: Learning About Systems

My first job after completing my master’s in psychology was at a community mental health center running therapeutic groups on an inpatient psychiatric ward of a hospital. Like many such facilities in the 1970s, the majority of the population was female, the rate of recidivism was high, and optimal approaches for effective treatment seemed an iffy proposition. Medication regimes combined with time on the unit, some group therapy, and occupational therapy were the tools of the day.

Out of a desire to experiment with new approaches, our team submitted a grant application to the NIMH (National Institute for Mental Health) and received funding to work with the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic conducting a two-year study providing systemic family therapy to both the identified patient and all members of the family. Our goal was to create sustainable mental health and reduce the rate of return to the hospital setting. The Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic was at that time home to the well-known Salvador Minuchin, who along with Jay Haley and others brought family systems therapy into the mainstream in the United States.

The Power of Systems

The first step was training several of us in a family systems approach. This step was equal parts mind-blowing and transformative for those of us on the team. We initially struggled and resisted as the systems approach turned our thinking upside down relative to the individualistic patient approach to treatment and the provocative and dynamic work of family systems thinking. As clinicians, we conducted every session behind a one-way mirror with a “bug in the ear” technology, thus allowing another member of our team to intervene with a new approach in the moment in our ear.

To shift gears from an individualistic focus on the patient to a systems approach wherein the identified patient was simply the carrier of the family pathology was truly a paradigm shift. This systems study taught us all so many lessons: first and perhaps most importantly, the power of clear boundaries; second, the basic tenets of systems thinking—no blame, no collusion, no triangulation, and ultimately, no revolving door! It taught us how quickly we look for the problem in one person. We identify the issue as a person instead of viewing an issue as systemically based, supported, and sustained because of the dynamics in the system. Read the following vignettes and use them to locate where you would land on the boundary continuum.

Using What’s in the Room: When Life Feels Unfair!

Omar arrives at coaching feeling annoyed and shares this scenario with you as the session begins: “I’m in an unfair situation and it’s getting worse. My co-worker, John, is constantly taking credit for work I initiated, for ideas that came straight from me and what’s really maddening is that no one else gets this.” As his coach, you are listening to your client express his annoyance at the way he has been treated by another member of his team: What happens inside you? How you manage your own boundaries makes all the difference. If your boundaries are at the permeable end of the continuum, you could find yourself getting drawn into his story and perhaps wanting to blurt out, “That is outrageous; I can easily see why you are so upset.” If you stepped over the boundary and took this approach, you and your client would be engaged in blaming and complaining, but no change would happen. A response wherein you maintain a clearer boundary might be: “So, you feel like you’ve been treated unfairly and I can tell from the quiver in your voice that even talking about this revives your anger. Could we take this apart a bit and see if there are any adjustments you could make that would change this scenario at all?” In this response with a tighter boundary, you are able to observe Omar’s story and mirror it back to him instead of getting drawn into his story.

Using What’s in the Room: Work Is Okay but Home Life Is Falling Apart!

Beatta arrives at a coaching session and opens up with the following: “Our focus on my leadership approach is going so well, but honestly what is really getting me down [tears showing up] is my home front. My daughter is sort of . . . well, really out of control. It’s her junior year when grades matter, getting into college is a big deal, and instead we are arguing about curfews, parties—we’ve even had some drinking incidents. The whole situation has me up at night worrying. What do you think I ought to be doing? Have you had any experiences like this with your kids?”

When a client comes to the session hurting and close to tears because of a very tough challenge with one of her children on the home front, what happens next and how you manage your boundaries once again makes all the difference. If you find yourself at the permeable edge of your boundaries and particularly triggered by her tears and sadness, you might find yourself jumping into her story and saying something like, “Wow, I’m so sorry and I’ve been there with one of my kids. I know how hard it is when something is challenging with our children, but you can’t blame yourself and I’m guessing it will turn itself around.” Or, a more boundaried response where you can stay out of your client’s story might be: “I can hear and see your pain; shall we step back from our work and take a look at what you are up against and see if there are some additional resources that might be useful?”

Again, when our boundaries are wobbly and porous, we get lost in our client’s story, drawn into their drama. When our boundaries are firmer, we are able to help the client step back and see their stories and situations with fresh eyes.

Using What’s in the Room: The Client Who Frequently Cancels

You are midway into a full day of coaching and in between sessions you pick up this voice-mail message: “Oh, coach, I’m so sorry to do this again but I’ve got a deadline I didn’t see coming and I won’t be able to make it today. See you in two weeks.” This is the fourth time and each time it is the same day and it throws your schedule off, and frankly, it’s annoying. How you approach this issue at your next appointment depends in part upon how you manage your boundaries! If your boundaries are permeable, when your client arrives apologizing for the last cancellation, you’ll likely say, “Oh, no worries, I understand things come up,” while all the while fuming underneath the surface. If your boundaries are strong, when he arrives and apologizes for the last cancellation, you might say, “I appreciate the apology, but more importantly, I find myself wondering if this happens just with me or if it is something we ought to take a look at that is happening in other places and may be important to our work?”

Permeable boundaries mean we can quickly jump to the other’s experience and overidentify with our client, making it difficult to add maximum value in the work. It may mean we are prone to want to make things okay, collude with our client to ensure comfort, or rescue our client, or add value by doing.

Stronger boundaries allow us to consciously notice when we feel tugged to collude, but we resist; when we have an urge to rescue our client, but we resist; or when we want to add value by taking on the work that belongs to our client, but we resist.

Origins of Boundary Management

Family systems therapist and well-known author on the topic, Murray Bowen (1985), uses the terminology of the differentiated to undifferentiated continuum to explore one’s ability to maintain boundaries. He describes the undifferentiated self as the degree of our unresolved emotional attachments to family of origin. He has written, “The degree of unresolved emotional attachment is equivalent to the degree of un-differentiation.”

We all operate on a continuum of boundary management: what Bowen referred to as levels of differentiation. Each of us is impacted by our generational history, our family relationships with parents and siblings, and by our own conscious work on self through the course of our adult years.

At our best differentiated self, we have a sense of integration about our self and a belief that we are responsible for our own sense of well-being, our challenges, and our messes. At our lowest level of differentiation, there is much more pervasive experience of anxiety and a sense that others are responsible for our well-being and sense of happiness and contentedness in the world. Check in on your own differentiation orientation. You might pause and consider a recent coaching engagement or two, perhaps one you felt went particularly well and another that was challenging and left you with more questions than answers. As you look through the chart below, you may find that your boundaries are different and your challenges are shifting with different clients. In Table 7.1, which of the experiences are common for you?

Table 7.1 Locating Your Boundaries

Diffuse Boundaries (rescue) |

Agile Boundaries (responsive) |

Rigid Boundaries (rebuff) |

|

|

|

We are all somewhere on the path reaching toward increasingly differentiated boundaries. This is a journey for each of us and it is an ethical path, as well. One dynamic we can all count on is the predictability that when under stress, we will be drawn toward a less differentiated place in our self. The trick is in noticing when this occurs.

Reducing the Urge to Rescue

When our boundaries are balanced—not too rigid nor too porous—our coaching is stronger because we are able to stay out of our client’s stories and stances and instead help them see the edges of their stories and patterns. With this balance there is less likelihood we will fall into the rescue trap. The urge to rescue is a trap because we become a part of the client’s story instead of helping them see their story. When we rescue, we collude with the client’s story and beliefs instead of exploring those beliefs. When we rescue, change does not happen.

Our drive to rescue can be complicated and a common refrain to justify this urge is I want to add value. Kets de Vries (2014) adds another perspective, reminding us that often the urge to rescue is fueled by “a disease to please,” rendering us ineffective as coaches. Our work is in our ability to step back, pay attention, recalibrate, and move forward. Reflection is the first step to change as a coach and as a client. Consider how you would answer these questions today and return to them in a week or two and see if your responses change:

- Do you feel best about yourself when you are helping and attending to others?

- Do you find it difficult to make time for yourself?

- Do you take your client’s issues and challenges home with you at end of day?

- Do you have a hard time saying no to a request even when you are not keen on it or it is a serious inconvenience?

- Do you sometimes feel angry or resentful about the time it takes to help another person?

- Do you find yourself at your best when there is a crisis to solve?

Systems Thinking

We tend to blame outside circumstances for our problems. “Someone else”—the competitors, the press, the changing mood of the marketplace, the government—did it to us. Systems thinking show us that there is no outside/that you and the cause of your problems are part of a single system. The cure lies in your relationship with your “enemy.”

—Peter Senge (2006)

When our boundaries are strong it is easier to engage in systems thinking and imagine all parts of the system. Perhaps the most important message in management guru Senge’s quote is quite simply that there is no one to blame! In his well-known book about learning organizations, The Fifth Discipline (2006), he puts a spotlight on the five essential disciplines including personal mastery, mental models, shared vision, team learning, and systems thinking. Combining Senge’s description of systems thinking with the family systems work of Murray Bowen (1985), we can distill the main concepts relevant in coaching, remembering that our exploration of boundaries is interconnected with systems.

System’s Thinking Concepts for Coaching

The following are general guidelines for how systems thinking and boundary management show up for us in coaching.

- Homeostasis rules: This concept originates in the field of biology and it is equally relevant for us as human beings. We seem to gravitate to a static state of being we are accustomed to even in the face of evidence our habits do not serve us best. The gravitational pull toward what we know, our comfort zone, is always at play. This is true for us as coaches and true for our clients. This means that our own resistance to change as well as our client’s ought to be expected and appreciated by us as coaches.

- There is no single root cause, no one to blame: We human beings imagine that when something goes wrong in our world it is because of someone or something outside of us. Somehow the act of blame is a form of self-vindication that takes us off the hook for exploring our role. Systems thinking challenges us to see the whole system instead of moving to a blame position.

- Everything is interconnected with everything else: There are no discrete actions or outcomes inside a system; everything is interconnected. Failures, successes, and learnings are all interconnected and the search for the source is antithetical to systems thinking.

- Triangles are the basic building blocks: Once three humans are in place we have a system. Triangles diffuse tension without going to the source, so triangles at play in a system can cause toxicity when allowed to replace straight talk and feedback.

- Systems have patterns we can learn from: It is in patterns that the possibility for change arises. Our attention to our own patterns combined with a deep presence allows us to observe patterns in others.

- Failure is discovery in disguise: Our best learning comes from our highest quality failures.

- Small interventions can have a big impact: All interventions that are workable are small. Change happens in small incremental steps, not in giant leaps.

- Most of what occurs in systems is not personal: Some say that at least 80% of what happens in a work environment is not personal and yet we often jump to the conclusion that it is personal and misinterpret what has occurred through our singularly focused lens of self.

Take a look at these short vignettes illustrating some of these systems concepts and see if they sound familiar to you!

“No One Ever Tells Me” or “Systems Have Patterns”

As a leader, one of your valued employees comes to you and complains that he was being left out of the loop, almost suggesting it was a purposeful act delivered in a mean-spirited manner. As you explore the details, a pattern emerges. The team member doesn’t ask or request the information he needs but instead waits and hopes someone will bring it to him. Those who have the information find it annoying he doesn’t take initiative to get the information. This is an ineffective team pattern and a small systemic intervention made on a few occasions could have a big impact.

“When Sarah Moves Fast, Barrett Moves Slow”; or “Barrett Moves Slow to Manage Sarah’s Speed!”

Sarah and Barrett are on an innovations team focused on two important pilot projects. They both find the other’s working style a little frustrating and each believes the other is the problem. According to Sarah, she thinks quickly and likes to iterate rapidly and when she brings her ideas to Barrett he puts the brakes on and all of a sudden, she has to figure out how to manage Barrett instead of moving the project forward. Barrett sees it quite the opposite. He believes Sarah moves way too quickly and makes mistakes that ultimately slow them down if they go unchecked; so, he has adopted an approach of slowing down in order to manage her speed, hoping to increase the likelihood of success of their project. Systems have patterns we can learn from.

“Yes, I Really Do Want to Change”

Uri comes to coaching knowing he needs to make some changes if he is going to get the promotion he dearly wants. He has been passed over three times and he’s started to realize he plays a role in this, and he must have a blind spot. He comes to coaching to focus on increasing his approachability and connection. You do a series of stakeholder interviews and his original goal is confirmed as the important one, and the lack of approachability and connection is even greater as viewed by his stakeholders than he perceives. The work proceeds and even while Uri says he wants to change, even while you’ve jointly crafted some action steps that will increase his way of being with others, each week he returns to coaching and nothing has changed. Homeostasis rules! Until Uri and the coach can uncover the obstacles getting in the way of adjusting his behavior, the homeostasis will prevail.

DEEPENING YOUR IMPACT: BUILDING MORE DIFFERENTIATION

| Practice | Impact |

| Notice where the boundaries are in your day-to-day life. | This is the first practice in building even stronger boundaries and deepening your differentiation. We are often so wrapped up in the business of our daily routines that we are not aware of how many boundary opportunities there are for us to stand at the edge of with more clarity and certainty. |

| Stay out of other people's stories so you can be fully present for them as you listen. | Notice the triggers that start to draw you in and use the triggers to signal stepping back, pausing, taking a breath, and re-centering. |

| Keep communication clean by de-triangulating. | Make an agreement with yourself to practice speaking directly to the person you are troubling about and avoid talking with a third party about the other person. The impact is immediate. Nothing changes when we talk to one person about another – it's just a way of letting off steam, complaining, or blaming. |

| Get clear on your yeses and nos. | Peter Block has long said, “Your yeses don't mean anything until you can say no.” Saying no when it matters is a good way of practicing clear boundaries. All too often, many of us say yes when we would like to say no, and the impact on us and others can be significant in bad feelings, resentments, and unspoken bargains. |

| Know what matters to you at this time in life. | When we are fuzzy about the future, where we are going, and what matters most, our boundaries get blurry and we can find ourselves led by someone else's agenda. |

THE COACH'S WORKSHEET: DEVELOPING MORE RANGE

Visit www.selfascoach.com for an opportunity to step back from each chapter and reflect on what meaning it has for you and what practices you might develop to keep honing your capacity as coach.

Applying Heat: Case Vignette II

CASE VIGNETTE #2: OVERWORKED AND OUT OF CONTROL

You’ve entered into a coaching engagement with Jana, a leader in her early thirties who has recently been promoted to a senior director role. She arrives at coaching excited about her new role and wanting to take a look at what she will need to adjust to hit this new role “out of the park.” She has spent her career in the tech industry and is smart and accomplished in this domain.

What unfolds in the discovery portion of the coaching is a picture of Jana working all hours, all days, all the time. She describes her life as “riding a train that is always on the verge of being out of control.” While her academic and work history are stellar, she describes an underlying insecurity about being able to hit the mark, driving her to overwork, taking on too much, and resorting to overly controlling behaviors in an attempt to hit that mark.

Over the course of the first several sessions, what you’ve noticed is a sensation that you, too, are on a train that is on the verge of going out of control! Each session, as you attempt to zero in and focus on what the client articulates as the most important work, it seems there is another fire that has shown up and Jana wants to refocus on it. Unlike most coaching, at the conclusion of these sessions you notice a sensation of feeling drained.

Here’s how three different coaches might approach this situation with the lens of each of the Self as Coach domains applied to enhance the applicability and relevance of the model.

Coach 1

Coach 1 wonders if he missed something in the early contracting conversation about what coaching is and how it unfolds. He worries that what Jana wants from him as coach is to simply help her put out fires and move from one issue to another in each session. He believes he has built trust and respect and he feels Jana’s pain relative to her nearly out-of-control train and her underlying insecurity. He is concerned he is not helping her, and he finds himself worried about her between sessions.

Where Coach 1 Is in Each of the Six Dimensions

- Presence. The coach finds himself distracted by his inner chatter and this has the natural potential to reduce his presence. This limited presence makes it difficult for a coach to pay full attention to what is unfolding in the session.

- Empathy. The coach reflects on his working alliance and believes he has developed a strong connection. This all-important connection will prove invaluable as the coaching unfolds.

- Range of Feelings. The coach seems able to contain the client’s feelings and this, again, allows the client to explore what is most important to her in the coaching engagement.

- Boundaries and Systems. The coach finds himself a bit drawn into his client’s situation and notes that he wants to help her and worries about her between sessions. Once drawn into the client’s story and sense of urgency, the coach is likely rendered less effective in helping the client observe herself and her story.

- Embodiment. The coach doesn’t offer any comments relative to his physical stability or how centered and grounded he feels during the sessions.

- Courage. The coach is able to notice the overarching themes and patterns of fires and the train she references, but his desire to help her (getting drawn into her story) makes it difficult for him to step out on the balcony and share observations and patterns that might prove useful to his client.

Coach 2

Coach 2 finds that it takes conscious work to stay present and centered in the presence of this client and when he accomplishes this, he sees a powerful connection between the metaphor she describes—riding a train that is on the verge of being out-of-control—and the experience he has as Jana arrives at coaching with another fire she is putting out and wanting to talk about with him. While he believes he has a good working alliance with Jana, he worries about how he might surface this connection with Jana without making her feel badly, especially in light of what she has shared about feeling inadequate.

Where Coach 2 Is in Each of the Six Dimensions

- Presence. The coach tells us he is actively engaged in being present and he mentions his presence increases his ability to see more clearly connections between what the client describes and how she shows up in the coaching sessions. When our presence is strong, we observe the moment and our client with increased clarity; we notice nuances of language, patterns, somatic signals, and more.

- Empathy. The coach believes the working alliance is strong and this enables him to explore with the client what is most important.

- Range of Feelings. The coach doesn’t reference the feelings domain, but given his presence and empathy are strong, one might expect his range of feelings has been cultivated, as well.

- Boundaries and Systems. The coach finds himself a bit drawn into his client’s situation and notes that he finds he is worrying about making her feel badly. Once drawn into the client’s story, he is likely rendered less effective in helping the client observe herself and her story.

- Embodiment. The coach mentions his conscious intentions around getting present and centered in these sessions.

- Courage. The coach is able to notice the overarching themes and patterns of fires and the train she references, but his worries about making her feel badly (getting drawn into the client’s story) limit his use of courage in sharing observations that might prove helpful to this client.

Coach 3

Coach 3 believes he has developed strong rapport with Jana and he finds her ability to viscerally describe her experience—the intensity, the almost-out-of-control train, the underlying insecurities—a real support in being able to explore this terrain together. He finds himself experiencing a parallel train ride, much like she describes, each time their coaching session unfolds. When he believes his connection is strong enough he shares this parallel observation. He is particularly careful to share it with heart because of all she has shared about her insecurities. The first time, he says something like, You mention this experience of traveling on a nearly out-of-control train, such a helpful description and observation and, you know, I find myself sharing that experience as you bring in these important situations that are on your mind. I wonder if you notice this intensity in our discussion as we talk? I wonder if there are any ways we might look at this together?

Where Coach 3 Is in Each of the Six Dimensions

- Presence. The coach appears to be fully present and able to reflect in the moment about what is unfolding.

- Empathy. The coach reflects on his working alliance and self-assesses that he has developed a strong rapport. This proves essential in deeper explorations.

- Range of Feelings. The coach seems able to fully appreciate his client’s feelings as well as reflect on his own. This allows the client to go where it is most important in the coaching engagement.

- Boundaries and Systems. The coach finds himself a bit drawn into his client’s situation and notes that he has an urge to help her, but he resists by strengthening his boundaries and this allows him to get on the balcony (more on this in Chapter 7) and observe patterns and stories that may prove helpful to the client.

- Embodiment. The coach doesn’t offer any reflections relative to how centered and grounded he might be during the sessions, yet his approach suggests he is able to find ways to keep himself grounded.

- Courage. The coach is able to notice the overarching themes and patterns of fires and the train she references, and he is able to step out on the balcony and share observations that might prove useful to his client.