CHAPTER 3

Making and Sharing Digital Photographs and Open-Source Cameras

Taking and Sharing Digital Photographs

We all take pictures, and many of us are already used to sharing them with our friends and family on social networks, as in Figure 3.1. However, to enable any photograph you take to be free and open source, whether with a professional camera or with your smartphone, you need to upload it to the Creative Commons. In other words, it must be uploaded to a website that allows you to share it with a license that allows others to freely use it. This is far less challenging than it sounds. There are many websites that make this easy, and here we will look at just three.

Figure 3.1 A man and a woman taking a selfie. (CC0) https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-man-and-woman-taking-selfie-1371176/

Pixabay (www.pixabay.com) allows you to upload/download royalty-free stock photos, vector graphics, illustrations, and videos and to share your own photographs in the public domain (Creative Commons zero [CC0]) with people all over the world. You can choose from a large selection of public-domain images; download them in small, medium, large, or original (supersized) formats; and use them any way that you would like. Pixabay allows comments, tags, and categorization. As of this writing, it has more than 750,000 images from which to choose.

Pexels (www.pexels.com) is another website to share your digital images. It similarly follows the CC0 license, which means that the pictures are free for personal and even for commercial use. You can modify, copy, and distribute the photos without asking for permission or setting a link to the source. In addition to the size choices from Pixabay, Pexels also lets you input a custom size so that you can download exactly what you want. There are dozens of other websites that offer similar images, such as Public Domain Pictures (www.publicdomainpictures.net). In addition to presenting a standard sharing platform, the site also has compiled a selection of photography tutorial videos that may be of great help to a new photographer. Several of the illustrations in this book (e.g., Figure 3.1) and in many other books have come from talented photographers who have provided images on Pixabay and Pexels.

Digital photographs have real value. This value becomes apparent to everyone who has to pay for it. For example, Getty Images, a commercial stock photography website, charges $175 to $575 for a single image depending on the size (although special images go for far more). People all over the world need good photos that are appropriately tagged for decorating websites, writing reports and books, and engaging in other creative acts. As Chapter 4 will show, there are even several free and open-source programs that enable you to take photographs and then turn them into other forms of digital art. The more material these creative people have to work with, the better are their products. The more others share, the better your projects will be too! Much of the work we all create will be fed back into the commons and result in more value for you.

There are several incentives that such photo-sharing websites use to encourage uploading. These include micropayments, tips, monthly contests, peer recognition, download stats as a vehicle for personal pride, and the ability to increase social media following, which comes with its own list of benefits (e.g., you could be a paid “influencer”). The simplest websites at least enable you to track the use of your images. You can also do this manually using a Google image search to see how often your pictures are used on the web. Go to Google Image search, and then drag and drop your picture into it. The results will show you the other places that your picture shows up on the web.

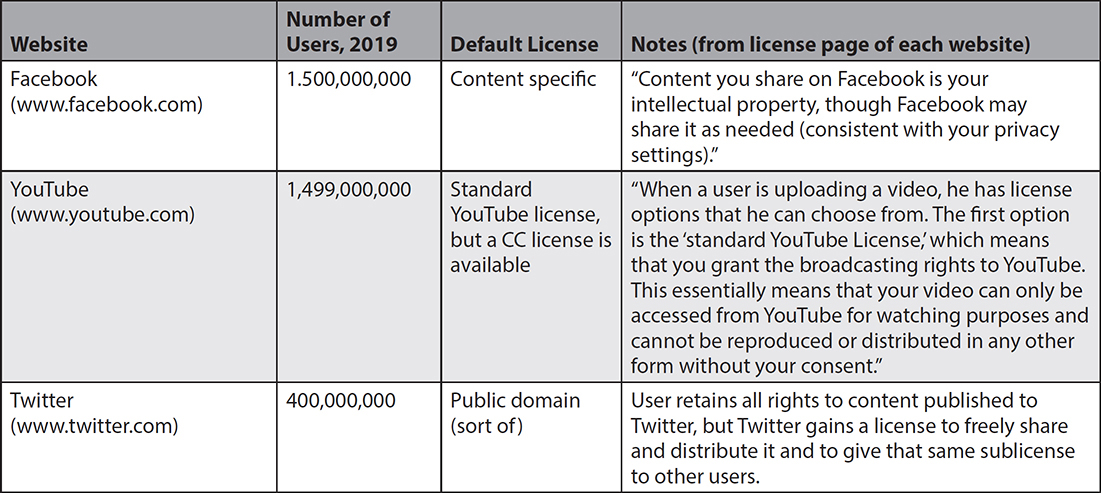

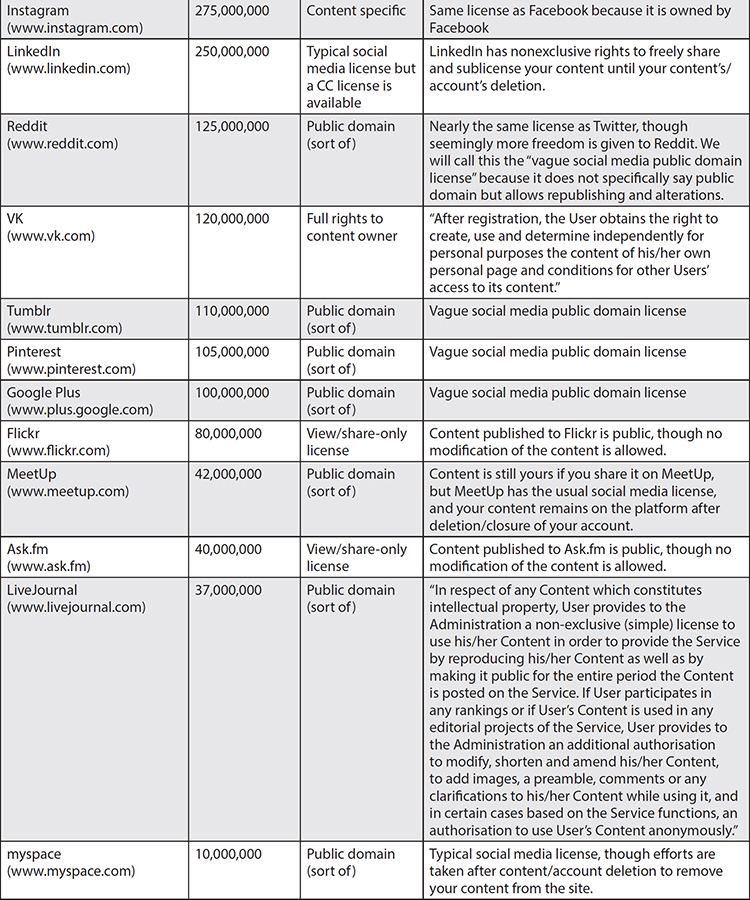

You are probably already well aware of many social media sites that enable you to share photographs. Most users of social media websites have never looked at the fine print on exactly what the licenses are for sharing their content. If you post a picture on Twitter, who owns the copyright? Did you give it away? Can others use it? What about Facebook? LinkedIn? Or the other social websites? To get a handle on the default settings for photo-sharing sites, please see Table 3.1. Sadly, as you can see in this table, most of the social media sites have somewhat obtuse licenses. It would be far better if they specifically classed them in the public domain or made a Creative Commons license the default. A few of the social media sites allow you to select this option, but the vast majority of users are subject to the default and somewhat unclear license.

Table 3.1 Default Licenses for Social Media

Free Software for Photo Lovers

There is also a lot of open-source software that can help you take and finish your pictures. For example, DigiCamControl (digicamcontrol.com) is open-source software that helps you control your camera settings remotely from your computer. You can hold the camera, shoot, and have the resulting images displayed on the computer monitor.

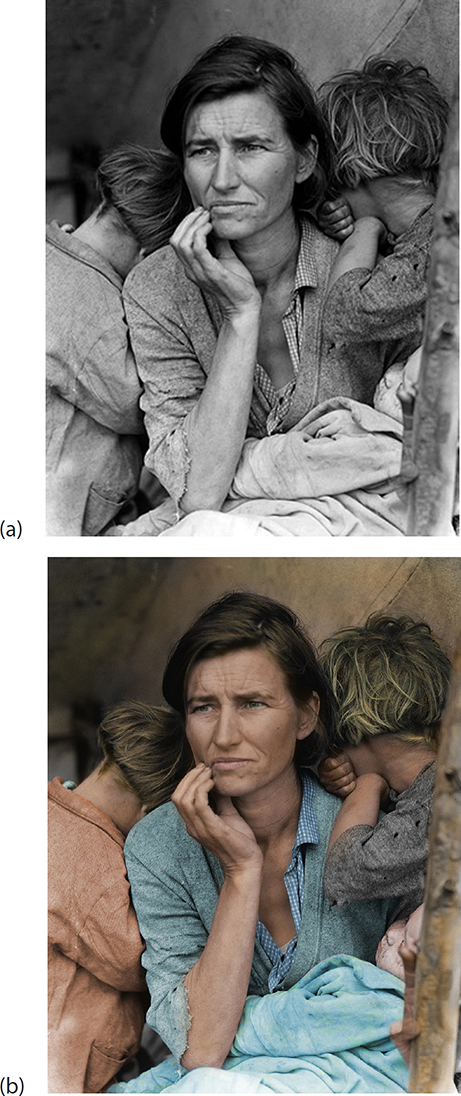

If you need to improve your photographs before you post them, the Gnu Image Manipulation Program (GIMP; www.gimp.org) is free, open source, and relatively easy to use. GIMP can do professional cropping, color correction, brightness control, contrast correction, and many other standard image-processing routines. GIMP also comes with a long list of artistic filters that can be extended to provide for full-featured photo touching. For example, Figure 3.2 shows the before and after colorization with GIMP of the Great Depression photo “Migrant Mother” by Dorothea Lange. GIMP even has powers to make your vacation pictures much better. If you have been to any tourist destination recently—really anywhere in the world—you have probably noticed that there are too many tourists! This phenomenon now even has a name—overtourism. Locals in many tourist areas such as Europe and other popular destinations are fighting back and trying to cut down on tourists. This doesn’t help you when there are still dozens of people standing in the way when you want to get a picture of a famous statue, building, landmark, artwork, or natural wonder. GIMP to the rescue! You can use GIMP to make your photographs tourist-free with an open-source plugin called G’MIC. First, put up a tripod and take an odd number of pictures every 10 seconds or so for a few minutes as the hordes of tourists mill about. Load up each of your aligned images as a layer in GIMP. Run G’MIC. Then go to Layers, Blend [median], and make sure that the input layers are all visible. Then, finally, output to a new layer. This will take a bit of time, but you end up with a tourist-free shot of your favorite destination or sight—just like in the brochures!

Figure 3.2 Before (a) and after (b) colorization with GIMP of Great Depression photo “Migrant Mother” by Dorothea Lange. Colorized by John Boero. (Public domain) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MigrantMotherColorized.jpg

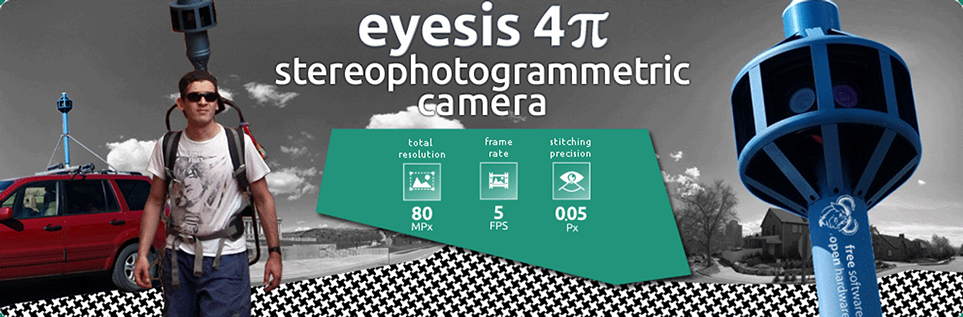

Open-Source Cameras

Open source doesn’t have to stop with the images or software to sort and edit them. Even the tools you use to take your photos can be open source and fully hackable. Elphel, Inc. (www.elphel.com) designs and manufactures high-performance cameras based on free software and hardware designs. The GNU General Public License (www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html) and the CERN Open Hardware License (www.ohwr.org/projects/cernohl) cover all the Elphel software and hardware designs. With open hardware camera companies such as Elphel, you have the option to buy the product that works out of the box like a normal purchase. Even better, you also have the possibility, and information needed, to modify any parts inside them. Elphel cameras have been used from everything from helping to capture images for Google Street View to taking pictures under the sea ice for surveying and exploring in Antarctica. The company has crazy cameras in its lineup. Consider the Elphel Eyesis4Pi-26-393, which is a full-sphere multicamera system for stereophotogrammetric applications, as shown in Figure 3.3. The free and open-source software that comes packed with it compensates for optical aberrations and preserves full resolution of the sensors over the field of view. You can use this for precise pixel mapping to automatically stitch images into breathtaking panoramas, which you may be familiar with. But it also allows for easy photogrammetry, which allows you to stitch your two-dimensional (2D) pictures to fabricate accurate three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions. You can walk into a building with this camera and walk out with a full 3D model of every room you enter. These 3D panoramas can be useful for everything from creating real settings for video games you are creating to giving your mom a virtual tour of your apartment when you are overseas.

Figure 3.3 Elphel Eyesis4Pi-26-393, a full-sphere multicamera system for stereophotogrammetric applications. (CC BY) https://www.elphel.com/wiki/Eyesis4Pi_393

Open-Source Software for Photogrammetry and Machine Vision

You do not necessarily need a fancy camera to enjoy the benefits of photogrammetry.

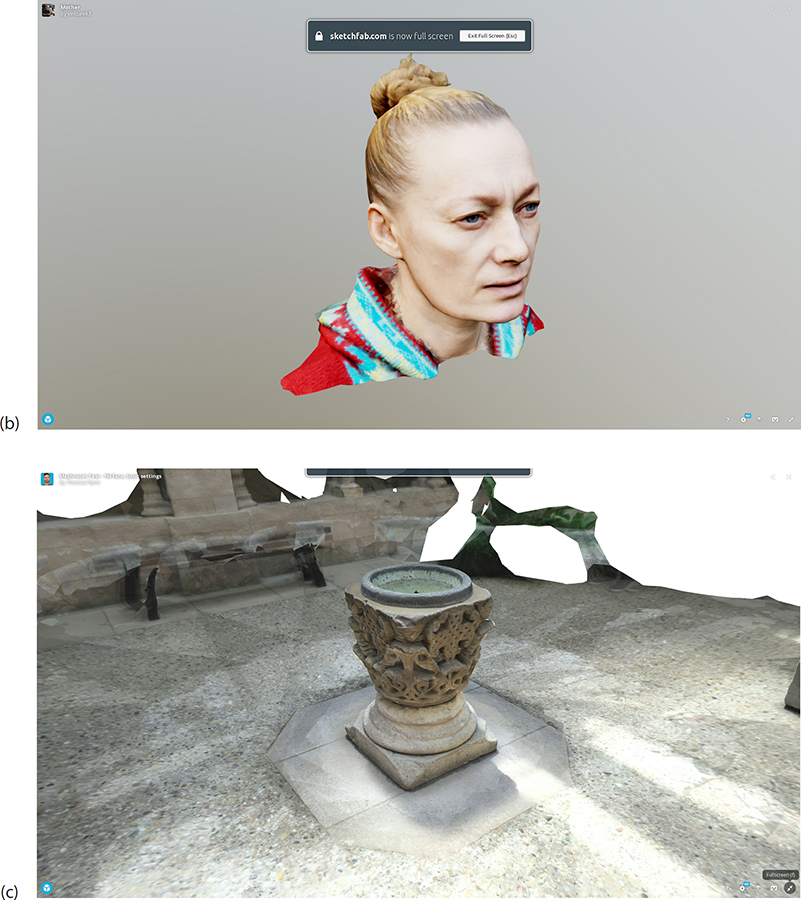

Meshroom (alicevision.org/#meshroom) is a free, open-source 3D reconstruction software based on the AliceVision framework. In the not-so-distant past, photogrammetry was extremely complex and hard to do. What Meshroom does is make it easy to do 3D reconstructions, photo modeling, and camera tracking just by taking a bunch of pictures with an ordinary digital camera or smartphone camera. The state-of-the-art computer vision algorithms that AliceVision uses are all open source, and you can dive into the code as deep as you like—but for most users you just need to follow some simple steps to create fantastic 3D models from just a few pictures. The models can be used to fabricate things (e.g., 3D printable models, as in Chapter 12) or to make ultrarealistic backgrounds for your open-source games or computer-generated imagery (CGI) movies. With your object being still (not moving), you take at least 30 (more is better) pictures from different angles and heights. You load all the images into Meshroom and hit Start so that it begins to match up the camera angles and build a 3D model of what you are aiming at (e.g., the landscape, person, and work of art examples shown in Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4 Screenshots of Meshroom examples: (a) Davia Rocks in Corsica. (AliceVision)(CC BY); (b) Mother (Meshroom with final touchups in Blender by Vincurek.f); (c) Saint Guilhem Cloiser Foundation (80 images processed with default settings by Thomas Flynn). (CC BY) https://forum.sketchfab.com/t/open-source-photogrammetry-with-meshroom/22965/5

Maybe you want to take pictures without being there, and you have had enough technical experience to be able to jump into a little computer code. There are several project options available in the open-source community for you. The OpenMV (openmv.io) project is creating low-cost, extensible, Python-powered, and machine vision modules for makers and hobbyists. OpenMV Cam is like an Arduino (www.arduino.cc) with a camera on board that you program in Python. It is easy to run machine visions algorithms on what the OpenMV Cam sees, so you can track colors, detect faces, and more in seconds and then control input-output pins in the real world.

If you want to learn more about computer vision (CV), the Open Source Computer Vision Library (OpenCV, opencv.org) is the preeminent open-source CV and machine-learning software library. The OpenCV community is particularly diverse and rich, with more than 47,000 people in its user community and tens of millions of downloads all over the world. There are probably others out there that have tackled a similar CV project to the one you might be interested in with OpenCV. Generally, they are glad to pass on tips because they were helped by others in the community. OpenCV has a very permissive free software Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) license, which imposes minimal restrictions on use and redistribution. This makes it really easy for businesses to use and modify the OpenCV code—so it is used all over the place.

The thousands of optimized algorithms that make up the OpenCV library help you to easily do the following:

1. Detect and recognize human faces

2. Identify objects (e.g., cars)

3. Classify human actions in videos

4. Track camera movements

5. Track moving objects (e.g., pucks during a hockey game)

6. Extract 3D models of objects or produce 3D point clouds from stereo cameras (which is handy for making the 3D printable objects we will talk about in Chapter 12)

7. Stitch images together to produce a high-resolution image of an entire scene for amazing vacation panoramas

8. Find similar images from an image database (such as the Google image search)

9. Remove those pesky red eyes from family photos taken using a flash

10. Follow eye movements (e.g., to help learn what people are looking at to make better education aids or to prevent car accidents from drowsy drivers)

11. Recognize scenery

12. Establish markers to overlay the photo with other software such as augmented reality

You can absolutely play with and use OpenCV like your own personal robot eye toy, but major companies—think Google (e.g., stitching streetview images together), Yahoo, Intel, IBM, Sony, Toyota, and many others—all use OpenCV. Many companies and individuals have contributed to making the algorithm libraries even more robust and available in C++, Python, Java, and MATLAB interfaces.

These open-source CV projects are maturing rapidly and becoming easier to use. Soon there will be apps that anyone can use with even the most modest computer experience. Today, you still need to be comfortable with a bit of programming—but luckily, the open-source community has provided oodles of tutorials that can train you in these tasks for your projects.