CHAPTER 6

Scanning, Making Paper and Audio Books, and Sharing Books

Open-Source Book Scanning

The idea that all of human knowledge belongs to all of us is a difficult concept to actualize in a world dominated by copyrights. The concept of copyright, however, is meant to provide authors with an incentive based on a monopoly for a given amount of time, after which the copyrighted work enters the public domain for everyone to enjoy. This is straightforward.

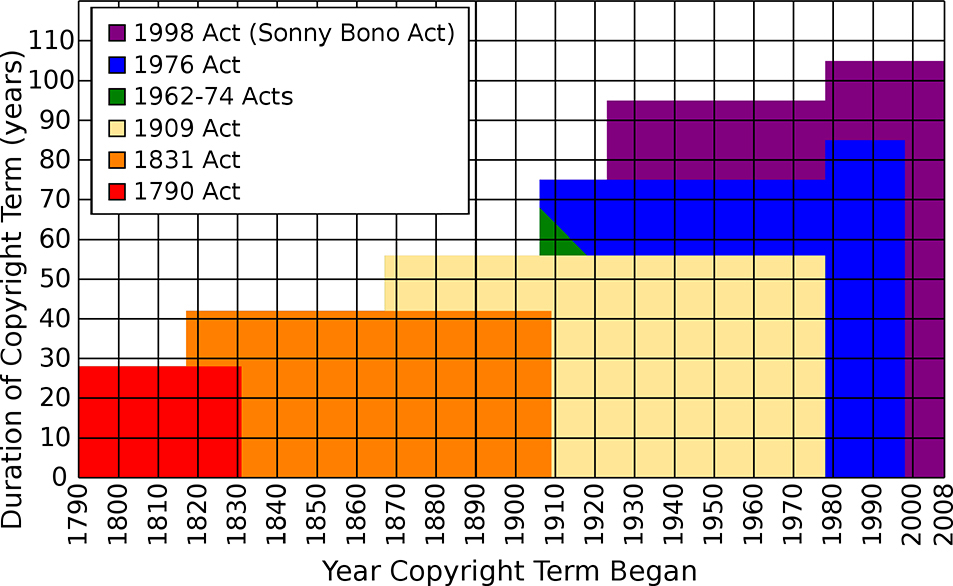

Things get tricky, however, when laws change to benefit a few at the expense of the many. This is illustrated in the expansion of copyright law in the United States, shown in Figure 6.1. Much of the time, these changes effectively took works in the public domain and reverted them to the old copyright owners, often even after the original author’s death. It is hard not to see the corruption in these changes in law. The 1998 Act extended the copyright of a poem you write yourself for your lifetime plus 70 years. Seventy years after you are dead! But, if you are working for a corporation to which you signed over the copyright of your poem as part of the terms of your employment, then it lasts for 120 years after its creation or 95 years after its publication, whichever end is earlier.

Figure 6.1 Expansion of U.S. copyright law (assuming that authors create their works 35 years before their death). Original author, Tom Bell, released this on his website. (CC BY-SA) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_Term_Extension_Act

This means that if the creator dies in the year of creation, the corporation has more rights than the creator (or his or her family). The same law holds for at least 25 years after creation and for any creative work that can be copyrighted, including music and sound recordings, websites, and printed works such as books. Why exactly should a corporation get rights to your work for 50 more years than you do if you made the work for yourself rather than as an employee?

Both the number of years and the disparity between individuals and corporations are pretty absurd, but proponents successfully argued in court three key justifications for the copyright extension: that public domain works will be (1) underutilized and less available, (2) will be oversaturated by poor-quality copies, and (3) poor-quality derivative works will harm the reputation of the original works. All three of these justifications were proven false in a detailed study that compared works from the two decades surrounding 1923 and made available as audiobooks (Buccafusco and Heald, 2013). This study found that copyrighted works were significantly less likely to be available than public-domain works, that there was no evidence of overexploitation driving down the prices of works, and perhaps most important, that the quality of the audiobook recordings did not significantly affect the prices people were willing to pay for the books in print (Buccafusco and Heald, 2013).

Despite these rule changes and corrupt laws, there is still a significant quantity of books in the public domain. These books can be legally digitized and shared with the world. If you have some of these old books, there are some open-source solutions, such as book scanners, to make the digitization easy. The cheapest way to make a book scanner is to use a single camera and a cardboard box (Reetz, 2019). Another super low-cost approach is to use a 3D-printable stand and a smartphone (RSID, 2018). However, many automated approaches have been developed by the do-it-yourself (DIY) book scanner community (www.diybookscanner.org) to preserve and share knowledge. You can buy a kit or build an automated book scanner from scratch from free plans.

For an industrial approach that does not hurt the book, consider the page-turning open-source Linear Book Scanner (linearbookscanner.org). Your book moves back and forth over the machine, and each time across, a vacuum sucks a page from one side to the other. As they are moving, the pages are scanned as they travel across two imaging sensors. The software that comes with the device produces a searchable PDF file of the book (e.g., providing added value over the original, which may have been printed long before computers were around).

Making Books

If you don’t have the patience to wait for the copyright to run out, an easier approach to making good books available in the public domain is to write them yourself! There are a lot of open-source technologies that can help you do this. The book you are reading now was written primarily on a Systems 76 laptop running Linux Mint (linuxmint.com). The actual typing was done mostly in Libre Office (www.libreoffice.org), a free office suite. Libre Office is more than good enough for most books. If you want to get fancy, there is also Scribus (scribus.net), which is a page layout program, or you could do the entire book in LaTeX (www.latex-project.org), which is a high-quality typesetting system. You can also use all the open-source photo-editing and art programs discussed in Chapters 3 and 4.

Making Audio Books

Another way you can help the global community and have a little fun with a book in the public domain is to make it into an audio book. This is easy with most computers or smartphones. Just read the book and record. You can clean up your recordings with Audacity (sourceforge.net/projects/audacity), a free audio mixer. When you are done, you can post your full audio version on LibriVox (librivox.org), which hosts free public-domain audio books.

Reading and Sharing Books

If you want to read the books you have scanned (or really any other books), there is a host of free and open-source e-book reading programs, such as Calibre, Cool Reader, and FBReader. As one of my colleagues explained, “The day I discovered the open-source FBReader application was like Christmas. For someone who likes to read a lot of stuff but has to deal with the issue of limited storage space, e-pub files are the perfect solution. The FBReader allows me to read anything, everywhere, and anytime. How cool is that?” My colleague is not alone. The multiplatform e-book reader FBReader (fbreader.org) is used by more than 20 million people throughout the world. It supports all the popular e-book formats: EPUB, FB2, Mobi, Rich Text Format (RTF), Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), Plain Text, and many more. FBReader also provides direct access to popular network libraries that contain a large set of e-books. Download books for free or for a fee, and you can customize the whole experience. There are a lot of places to get free e-books (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Free e-Book Websites

Project Gutenberg (www.gutenberg.org) is a good example of a free e-book website because it is a reasonable digital library with more than 60,000 free e-books that focuses on older works for which the U.S. copyright has expired. Project Gutenberg’s volunteers digitized these works, and now the site allows you to either read the books online or download them to use on your favorite e-book reader as either a free e-pub or even a Kindle e-book. Project Gutenberg makes it easy to join the open-source book community. Because everything on Project Gutenberg is completely zero cost, the site asks for help to digitize more books (see “Open-Source Book Scanning” earlier in this chapter). You can join the distributed proofreading and formatting group, record audio books at LibreVox (librivox.org), or even simply report errors. What Project Gutenberg does not do is help you publish and share your own book. To be included on the site, you need to be published already.

Maybe you have some ideas for the next great novel or even a children’s book, and maybe you are considering sharing it with the rest of the world with an open-source license. There are many on-demand book publishers now that will be more than happy to help you publish your book. Their printing costs are not overly expensive, particularly in bulk. However, it still gets expensive fast to make many hard copies of an open-source book available. It is much easier to share a digital version. There are also many websites where you can post a digital version of your book for free under an open license (e.g., at Freebooks [www.free-ebooks.net]) or target a specific genre, such as books for children (e.g., Free Kids Books [freekidsbooks.org]).

Cory Doctorow Makers

Cory Doctorow is the ex-director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (www.eff.org), which is the leading nonprofit organization defending digital privacy, free speech, and innovation. Doctorow is also a science fiction author who both writes full time and allows you to download all his books for free (craphound.com). Doctorow released his first novel, Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom. under a Creative Commons license, which allows readers to download the book for free.

Now all his books come this way. How does he possibly do this? To give you an idea, the first Doctorow book I ever read was Makers (craphound.com/makers), an excellent fictional introduction to the subculture of makers and how America might still have a happy landing despite all the negative trajectories we are on. Since then, I have purchased more copies of this book than any other book I have ever read—to give as gifts to my students. Yet Makers, like all of Doctorow’s other books, can be downloaded for free.

Doctorow explains his reasoning in three steps (Royal, 2013). He says that, realistically, it takes one or two clicks to download a book without having to pay for it anyway because illegal copies of most books are easily found. Therefore, by being generous and trusting his readers, he hopes that he can channel their energy into helping him. In other words, by sharing his book for free, he encourages more people to read it and thus more people will know about it and potentially buy a copy. He explains, “I’m not really concerned with being sure that everybody who reads my books pays for them. I’m much more concerned with making sure that everybody who’s willing to pay gets a chance to read them.” (Royal, 2013). Moreover, Doctorow feels that given today’s technological landscape, modern art (such as books) will be copied, so he derives artistic satisfaction from allowing people to copy his books. Lastly, he finds this approach to be moral because ever-increasingly draconian measures are being enacted to defend copyrights in this internet era, to make it as hard as possible to prevent copying.

This, of course, is not working. As Doctorow explains, “More people copy more things now than they ever did, but they are monotonically increasing the amount of surveillance and censorship on the internet. And as an artist, I think that it’s my duty not to have my works form part of the rationale for increasing censorship and control and surveillance on this amazing information medium that we all use for everything” (Royal, 2013). His solution is to avoid anything that leads you to demand censorship and surveillance on the internet.

Doctorow makes some powerful points (Doctorow, 2009). Most books hardly make any money and receive less readership than even the most benign, boring, and unimportant celebrity tweet. They will be available for free in minutes after publishing anyway, and yet most publishers are highly resistant to publishing open-access e-books. This puts authors in a challenging situation. Finding a publisher willing to publish a hard-copy book under a Creative Commons license is still pretty challenging.

Some publishers, particularly academic publishers, may be more receptive. My first book, Open-Source Lab: How to Build Your Own Hardware and Reduce Research Costs, was published by Elsevier, the largest scientific publisher. Because of the nature of the book, the company agreed to add a clause in the contract to make the book available for free, although it controlled how this would be done. What the company ended up doing was making one chapter at a time downloadable for free from its website each month. With patience, anyone could have the entire book for free completely legally.

Not surprisingly, however, shortly after the book was published, someone (or more than one person) uploaded a copy (or copies) to illegal download sites, and now there are free copies of it all over the place. Regardless, people still buy the book, and most important, I keep the information on that topic up to date on a CC BY-SA website (www.appropedia.org/Open-source_Lab). As discussed in Chapter 13, the academic community has turned the corner, so to speak. Open access in science writing and open-source software and hardware for science are becoming the norm.

This is not yet true for everything else, which brings us to the slightly uncomfortable topic of the copyright of the book you are reading now. Ideally, it would be open source as well, yet still published with the full support of a major publisher. For this book, I made the choice to partner with the publisher under a traditional contract because the publisher could provide the largest possible readership using conventional marketing. The core of this book—all the links and designs—is still open source and is available on the book’s website (www.appropedia.org/Create).

References

Buccafusco C, Heald PJ. 2013. Do bad things happen when works enter the public domain? Empirical tests of copyright term extension. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 1:1–43. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2130008

Doctorow C. 2009. Why free ebooks should be part of the plot for writers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2009/aug/18/free-ebooks-cory-doctorow

Reetz D. 2019. Bargain-price book scanner from a cardboard box. Instructables, https://www.instructables.com/id/Bargain-Price-Book-Scanner-From-A-Cardboard-Box/

Royal D. 2013. Author Cory Doctorow talks tech, Trotsky, what he’s reading, and why he’s giving away his books for free. Phoenix New Times. February 6, 2013. https://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/arts/author-cory-doctorow-talks-tech-trotsky-what-hes-reading-and-why-hes-giving-away-his-books-for-free-6570042

RSID. 2018. Document Book Scanner for CellPhone by siderits [WWW Document]. https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:3194536