CHAPTER 9

Making and Sharing Clothing

Much like the other areas of free and open-source design we have discussed, embracing open-source clothing provides you with far more options that you are accustomed to as a conventional consumer. Because of some vagaries of intellectual property law, the designs of clothing cannot be protected. In the fashion industry, innovation is fast because there is a general lack of artificial intellectual monopoly (Boldrin and Levine, 2008), and it is relatively easy to alter fashion design (Raustiala and Sprigman, 2012). This helps to explain why fashion is constantly changing styles (i.e., clothing companies cannot rely on 20-year patent protection, so they must innovate to keep selling products). When you look online for clothes or go to a major department store, it may at first appear that there is a lot of selection. At closer inspection, however, there are not that many options, and in a town with a few clothing stores, it is not uncommon for many people to be wearing the same thing—mass-produced items whose only customization is small, medium, and large.

Even well-known celebrities such as actress and singer Vanessa Hudgens and model and philanthropist Petra Nemcova battled it out over the same gold dress (Figure 9.1). The wealthy and famous don’t seem to be able to escape the relatively limited selection created by the mass-produced clothing industry, which explains the popularity of the media meme “Who wore it better?” The average person has very little clothing that is made to fit them exactly—perhaps a suit. With open-source clothing, everything you wear can be customized and made to fit you exactly. This provides a new creative and positive means to express individuality.

Figure 9.1 Who wore it better? Where Petra Nemcova and Vanessa Hudgens battle it out over the same gold dress. Hudgens is a famous actress and singer, and Nemcova is a model and the cofounder and vice chair of All Hands And Hearts (AHAH)—Smart Response, which is a nonprofit dedicated to providing fast and effective support to communities hit by natural disasters worldwide. Live & Let Die </3. (CC BY-2.0) www.flickr.com/photos/shout-it/4104493149

Free Patterns for Clothes

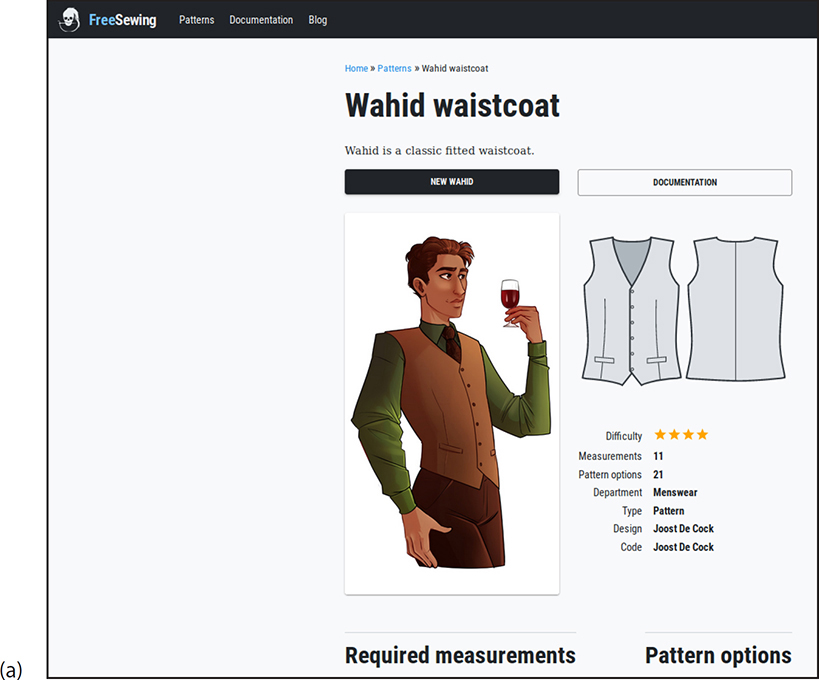

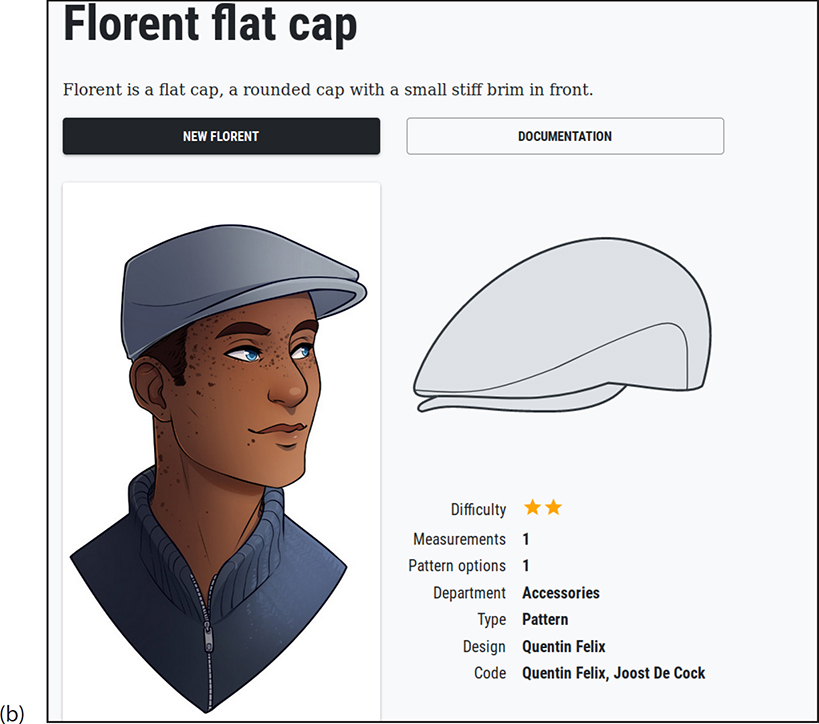

Many websites now offer free patterns for pretty much any type of person or style. For example, FreeSewing (freesewing.org) is an open-source platform for made-to-measure sewing patterns—think of it as the “Wikipedia of sewing patterns in its early days.” FreeSewing helps those who would like to make their own or loved one’s clothing using the combined knowledge of the sewing community, its patterns, and its complete documentation. FreeSewing gives all of its core designs names, such as the “Wahid waistcoat” shown in Figure 9.2a. The designs are rated by difficulty, the number of measurements that you need to take to custom design it, and various options. If the Wahid is a bit too much for you to get started on because of the complexity, there are simpler designs, such as “Florent Flat cap” that only needs a single measurement (Figure 9.2b).

Other, more conventional pattern houses, such as BurdaStyle, have been captivated by the open-source philosophy of sharing and allowing the public to adapt its clothing to each individual’s specific needs, so the company removed the copyright from its patterns (Style, 2009). The company’s open-source sewing patterns are free to be used as a base for your own design, which you can wear, gift, or sell. Whatever you sew, you can sell it if you like. Sew Daily has even started selling how-to videos using BurdaStyle designs (Figure 9.3). BurdaStyle hopes that open sourcing its designs will inspire creativity and spawn multiple new designs. Even high-end pattern companies such as Portia have gone open source. The company recognized that obscurity is a far larger risk than piracy. The company wants people to use and innovate its designs, and it only asks for attribution (Masnick, 2007). Many other firms behave similarly, providing free basic sewing patterns (www.moodfabrics.com/blog/category/basic-sewing-patterns and www.allfreesewing.com).

Figure 9.2 (a) Screenshot of Wahid waistcoat. FreeSewing. (Open-source MIT license) https://en.freesewing.org/

Figure 9.2 (b) Florent flat cap. FreeSewing. (Open-source MIT license) https://github.com/freesewing/freesewing

Figure 9.3 Screenshot of Sewdaily TV video How to Sew the BurdaStyle Short Jumpsuit (https://videos.sewdaily.com/courses/how-to-sew-the-burdastyle-short-jumpsuit). Open-source pattern can be downloaded from www.burdastyle.com/pattern_store/patterns/short-jumpsuit-052013

Making your own clothes also enables you to be a good environmental steward. You can repair clothes rather than discarding them in landfills. You can even use your old clothes to make new ones. In addition, one of the lowest-cost ways of getting fabric is to buy clothes on sale at secondhand stores and then disassemble them and make what you want from free patterns. Extralarge (XL) and bigger sizes are particularly good for this approach to the lowest cost per square meter of fabric. All these methods of up-cycling and reusing are good for the environment, as well as your pocketbook.

Open-source design does not stop with the clothing you wear on your back. It has also gone all the way down to your toes to create some truly one-of-a-kind shoe designs. A Fablab engineer in France designed the chaussures à talons (or “high heels shoes”) that can be digitally manufactured, and released them under a GNU GPL license (Figure 9.4). Thus, they are free for anyone to make, and more than 1,000 people have already made a pair. If you are into high heels and this is not specialized enough for you, the open-source community has gotten truly original. For example, inspired by the TV show Mr. Robot, Naomi Wu designed an attractive pair of platform heels that can also be used for information security penetration testing (e.g., spying or probing of security threats), as shown in Figure 9.5a. As can be seen in Figure 9.5b, in one shoe, there is a USB keystroke recorder, which is a pass-through device that goes into the back of the computer where you normally plug the keyboard in and records everything typed on the keyboard. This enables the collection of passwords, encrypted messages before encryption, and so on. Because Wu is an open-source hardware trend setter, the shoes also house a retractable Ethernet cable for the OpenWRT router (openwrt.org). Finally, no spy shoes would be complete without a full lock pick set housed in the other shoe.

Figure 9.4 Chaussures à talons—high-heel shoes by experience. (GNU FDL) www.thingiverse.com/thing:915618

Harnessing the open-source philosophy for shoes is not only done by makers. Following in the footsteps of free and open-source software (FOSS), Open Source Footwear gives everyone a chance to have a say in the shoes they want to see (www.fluevog.com/community/open-source-footwear). John Fluevog Shoes is a company that has essentially crowdsourced its designing work. If you have an idea for a new pair of shoes and want to see it in real life, you can submit your design for all to use. If the company likes your design, it will make you a pair and start to sell the shoes.

Figure 9.5 (a) Naomi Wu modeling her Wu Ying Shoes—Pentesting Platform Shoes; (b) the security-penetration testing tools that the shoes hide. (CC BY-SA) www.thingiverse.com/thing:980191

Open-Source Software for Automated Sewing

Ink Stitch (inkstitch.org) is an open-source machine embroidery design platform based on Inkscape (the vector graphics program we looked at in Chapter 4). You make or create a vector image in Inkscape, then covert it to embroidery vectors, plan the stitch order and attach commands, take a look at it with a built-in simulator, and finally, try it out in real life. Then people can share these designs too, like Silver Seams (silverseams.com/free-patterns/embroidery-patterns). In addition, using 3D-printed parts, you can convert any normal sewing machine into a computer numerical control (CNC) embroidery machine (inkstitch.org/tutorials/embroidery-machine). These same concepts are used in the other automated digital tools discussed in Chapter 12. Similarly, Seamly (seamly.net) and Valentina (valentinaproject.bitbucket.io) are open-source pattern design software, which are designed to be the foundation of a new stack of open-source tools to remake the garment industry. The Valentina project has a strong social mission because those behind it believe that small-batch and custom-sized clothing manufacturing is essential to

1. Create a sustainable future,

2. Preserve small- to medium-sized textile spinning and weaving manufacturers,

3. Enable independent and small designers and manufacturers to scale up to make a decent living,

4. Rebuild local garment districts, and last but not least,

5. Reduce or eliminate slave labor.

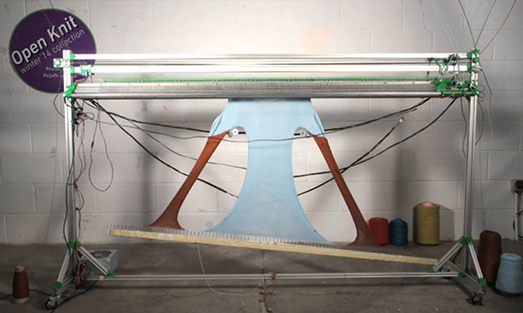

Open Hardware for Clothes Making

Although open-source ecology has called for an open-source sewing machine, little progress has been made on that front to date. Open-source knitting, however, is much further along. OpenKnit (openknit.org) is a low-cost open-source digital fabrication tool that lets you create your own custom-knitted clothing from digital files. OpenKnit takes you from yarn straight to its end-use clothing (e.g., a sweater, as shown in Figure 9.6). This is done with almost no waste, similar to a 3D-printed object, because the product is knitted to shape. OpenKnit enables the design of digital custom clothing and production of the clothes wherever you happen to be, providing a lot of opportunity to flex your creativity. In turn, you can use others’ digital designs or share your own at Do knIt Yourself (doknityourself.com), which acts as an open-source clothing platform to share clothes virtually and freely for anyone using OpenKnit machines and Knitic software (github.com/mcanet/knitic).

Figure 9.6 Screenshot of OpenKnit video fabricating a “Hello world” sweater. Openknit, a Reprap-inspired open-source knitting machine, 2014. Boing Boing. (BY NC-SA-3.0) https://boingboing.net/2014/02/20/openknit-a-reprap-inspired-op.html

Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Clothing and the Future

In the past, everyone made their own clothing. It was a point of pride and a way to demonstrate your skills. Perhaps we are headed back there with both old-school and high-tech methods of making custom perfect-fit clothes for ourselves. The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly made the value of distributed manufacturing (Pearce, 2020), and of sewing in particular, clear. Throughout the world, people are using open-source patterns for face masks (e.g., www.craftpassion.com/face-mask-sewing-pattern to make masks for their family, friends, and local hospitals to use in order to conserve N95 masks.

References

Boldrin M, Levine DK. 2008. Against Intellectual Monopoly. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Masnick M. 2007. Open Source . . . Sewing? Techdirt. https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20070413/110343.shtml

Pearce JM. 2020. Distributed manufacturing of open source medical hardware for pandemics. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 4(2), p. 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp4020049

Raustiala K, Sprigman C. 2012. The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Style B. 2009. What Is Open Source Sewing? BurdaStyle. https://www.burdastyle.com/discussions/getting-started/topics/what-is-open-source-sewing