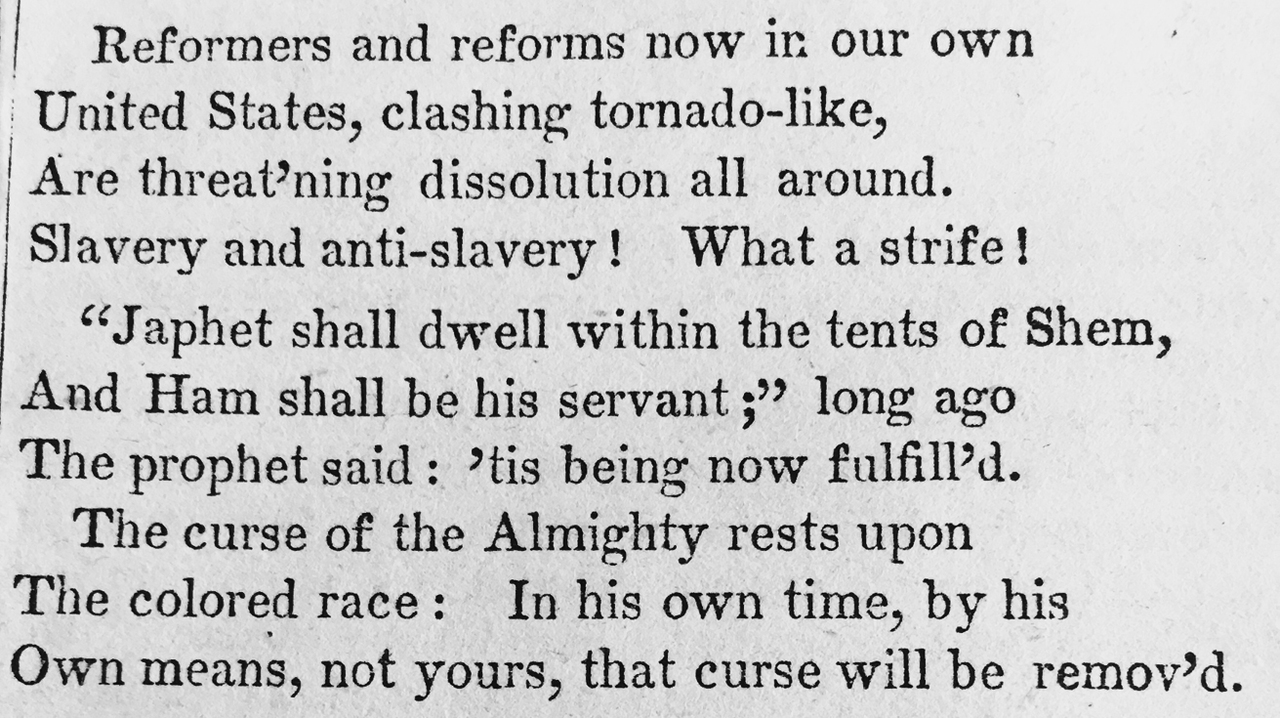

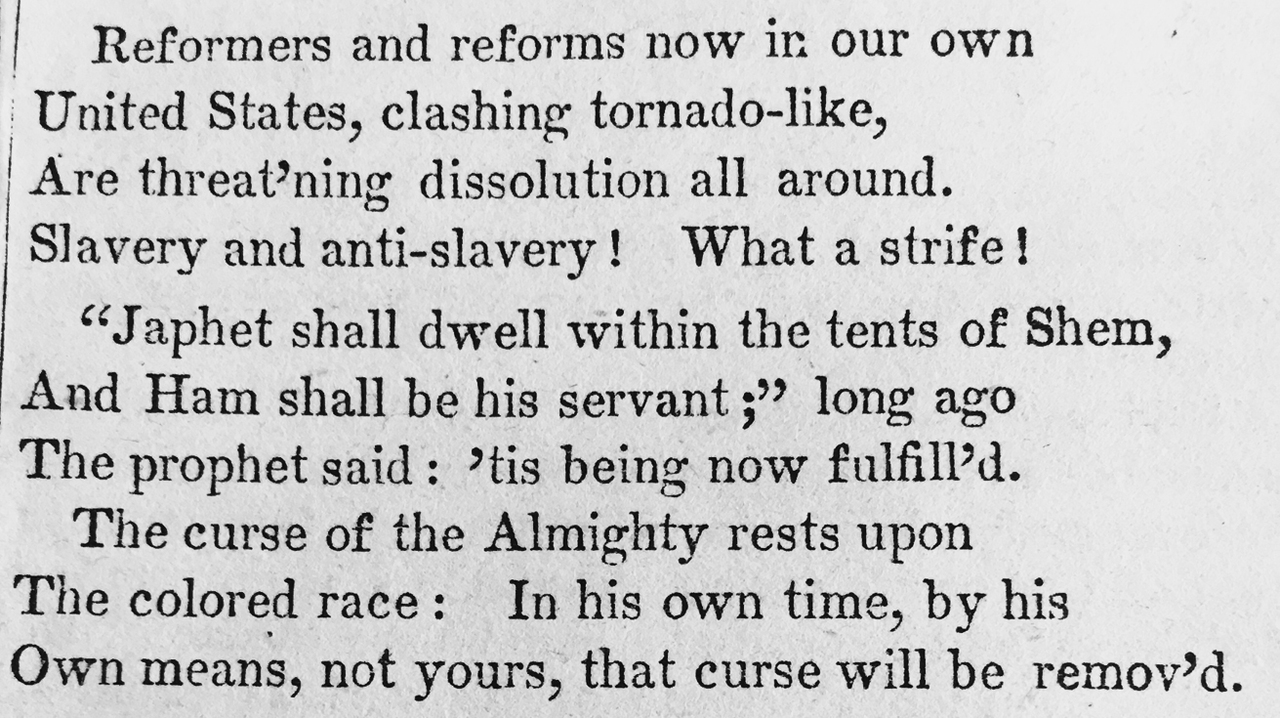

Figure 2.1. Excerpt from Eliza R. Snow, “The New Year,” published page 1, Deseret News, January 10, 1852.

Image courtesy of Marriott Special Collections Library, University of Utah.

White supremacy gains power through millions upon millions of micropolitical decisions that people who believe they are “white” make every day. I say “people who believe they are ‘white’ ” because historians have shown us that whiteness has not always existed. It is not a “natural” category of being. It is a modern invention. The idea that being “white” was good and valuable took shape over time as people who believed they were “white” preferred one another’s interests over the interests of those who were non-“white” and so began to consolidate group power. Noel Ignatiev, Karen Brodkin Sacks, and many others have observed that, if their skin color allowed and if their conduct did not contest white supremacy, minority groups in the United States, even new immigrants like Irish and Jews who were the objects of deep prejudice, could “become” white and enjoy at least some measure of its privileges.1 Thus developed what George Lipsitz has called a “possessive investment in whiteness.” He explains:

Whiteness has a cash value: it accounts for advantages that come to individuals through profits made from housing secured in discriminatory markets, through the unequal educations allocated to children of different races, through insider networks that channel employment opportunities to the relatives and friends of those who have profited most from present and past racial discrimination, and especially through intergenerational transfers of inherited wealth that pass on the spoils of discrimination to succeeding generations. . . . White Americans are encouraged to invest in whiteness, to remain true to an identity that provides them with resources, power, and opportunity. White supremacy is usually less a matter of direct, referential, and snarling contempt than a system for protecting the privileges of whites by denying communities of color opportunities for asset accumulation and upward mobility.2

American Christianity as practiced in predominantly white churches has played a role in cultivating the possessive investment in whiteness. It has delivered powerful symbolic and rhetorical validation of “white” as “holy” and “pure,” instituted and advanced segregation, and fostered the “insider networks” and “intergenerational transfers of inherited wealth”—how many people have been disowned for leaving the faith?—essential to white privilege. This is true even in churches with moderate and progressive political dispositions. In the late eighteenth century, St. George’s United Methodist Church of Philadelphia was among the most progressive in America. Methodist leaders opposed slavery, and the church ordained lay Black preachers and helped foster a Black worship community. But it also maintained a segregated seating policy restricting Black worshippers to the upper gallery. One morning during services in 1794, white ushers attempted to forcibly remove Black worshippers including lay clergy member Absalom Jones from their knees in prayer to enforce seating segregation, leading to a mass walkout of Black members and the foundation of Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Any room where white-identified people cultivate preference for one another over the unsettling and discomforting presence of the “stranger” or the darker-skinned “neighbor” is a room where white supremacy is being forged.

There are moments that flash up throughout the history of American Christianity that remind us that it was always possible to choose otherwise. We see these possibilities often in the originary moments of new religious movements, when faith is chaotic, charismatic, and capable of expansive and emancipatory possibilities. Over time, through millions upon millions of micropolitical decisions, movements settle into institutions. Almost without exception, when predominantly white American Christianities have institutionalized, because institutionalization often requires the physical and social capital that whiteness can confer access to, emancipatory possibilities have constricted. This chapter traces constituting micropolitical decisions through which the Mormon movement institutionalized and, in the words of historian Max Mueller, “contracted”3 its own emancipatory possibilities, decisions that consistently privileged white over Black.

* * *

It didn’t have to be this way. There were, it seemed at the beginning, emancipatory possibilities in Mormonism. These must have registered with Kwaku Walker Lewis, who joined the faith in 1843. Born free in Barre, Massachusetts, in 1798, his parents, Peter, a free yeoman farmer, and Minor, an emancipated slave, gave him an Akan name after his maternal uncle “Kwaku.” “Kwaku” had mounted two successful legal suits to win his freedom in 1781 and 1783, setting legal precedent for other freedom-seeking African Americans in the state of Massachusetts. By the age of twenty-eight, Kwaku’s namesake Walker Lewis had established a place for himself among the Black politically progressive professionals of the Boston area. A barber by trade, Lewis joined with David Walker and other noted early Black activists to form the Massachusetts General Colored Association, which in 1829 published David Walker’s famed Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, a ground-shaking radical rhetorical strike against white supremacy. David Walker served from 1829 to 1831 as grandmaster of the Prince Hall African Lodge of Freemasons, long the center of Black political organization and activism in the city, and in 1831, he assumed the presidency of the African Humane Society, a mutual aid organization that later sponsored Black emigration to Liberia; during the 1840s, he used his barbershop and his son’s used clothing store to outfit and disguise Black slaves heading north on the Underground Railroad. This was the kind of company Walker Lewis kept. In 1843, Lewis heard the Mormon message and chose to become a baptized member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He was ordained to the LDS Church lay priesthood by Church founder Joseph Smith’s older brother William, the third known African American Church member so ordained. The year was 1844: the same year Joseph Smith mounted a campaign for the US presidency, proposing in his platform that the United States sell public lands to purchase slaves and pursue their gradual emancipation, education, and emigration to places where they could be a free and self-determining people.4

Walker Lewis was held up in 1847 by Brigham Young as “one of the best elders” in the Church and as an exemplar of noble character. In March 1851, Lewis stepped away from his strong, deep ties to Boston’s storied free Black community and turned his face toward a different Zion, the one being attempted by his fellow Mormons in the American West. Lewis arrived in Salt Lake City in October 1851. He received his patriarchal blessing and proposed marriage to another prominent Black Mormon named Jane Manning James, who declined; she would have been his second (and hence polygamous) wife. But Walker Lewis did not stay in Utah territory for long. Within six months, he emigrated back to Lowell, Massachusetts, where he lived until he succumbed to tuberculosis in 1856.5

Surviving records provide no direct evidence as to why Walker Lewis left Mormon Utah in March or April 1852. But it does bear notice that in January and February 1852 the Utah Territorial Legislature under the leadership of Brigham Young had passed measures permitting a form of African American slavery in the territory and denying African American citizens in some municipalities the right to vote. Walker Lewis had education, experience, resources, and options, and he knew his own mind on matters of slavery and freedom. Who could blame him if his spirit could not accede to the politics of a slaveholding Zion?

And it was not the first time that white Mormons had for tactical and political reasons sacrificed the interests of their Black coreligionists. At no time in its founding decades had Mormonism established a clear theological or social commitment to inclusion and equality. The early Mormon movement (1830–1845) emerged solidly from within the context of mainstream American Protestantism in its disposition on matters of race. Its leaders and founding figures including Joseph Smith carried forward a mix of unexceptional attitudes on slavery—ranging from support for slavery to support for gradualist emancipation. Early statements and actions by Church leaders on matters of race reflect an incoherence and instability inflected less by Christian ethics than by licentious theological speculation and pragmatic adaptation to sometimes hostile political contexts.6 Under pressure from their host communities in the border and frontier states, early Mormon settlements did not throw in with the cause of Black emancipation.

The most famous example is W. W. Phelps’s printing in the Evening and Morning Star of July 1833 a notice to “Free People of Color” who might join the Mormon movement or its settlements warning them that Missouri was a slaveholding state:7

To prevent any misunderstanding among the churches abroad, respecting free people of color, who may think of coming to the western boundaries of Missouri, as members of the church, we quote the following clauses from the laws of Missouri:

“Section 4.—Be it further enacted, that hereafter no free negro or mulatto, other than a citizen of someone of the United States, shall come into or settle in this state under any pretext whatever; and upon complaint made to any justice of the peace, that such person is in his county, contrary to the provisions of this section, if it shall appear that such person is a free negro or mulatto, and that he hath come into this state after the passage of this act, and such person shall not produce a certificate, attested by the seal of some court of record in someone of the United States, evidencing that he is a citizen of such state, the justice shall command him forthwith to depart from this state; and in case such negro or mulatto shall not depart from the state within thirty days after being commanded so to do as aforesaid, any justice of the peace, upon complaint thereof to him made may cause such person to be brought before him and may commit him to the common goal of the county in which he may be found, until the next term of the circuit court to be held in such county. And the said court shall cause such person to be brought before them and examine into the cause of commitment; and if it shall appear that such person came into the state contrary to the provisions of this act, and continued therein after being commanded to depart as aforesaid, such court may sentence such person to receive ten lashes on his or her bare back, and order him to depart the state; and if he or she shall not depart, the same proceedings shall be had and punishment inflicted, as often as may be necessary, until such person shall depart the state.

“Sec. 5.—Be it further enacted, that if any person shall, after the taking effect of this act, bring into this state any free negro or mulatto, not having in his possession a certificate of citizenship as required by this act, (he or she) shall forfeit any pay, for every person so brought, the sum of five hundred dollars, to be recovered by action of debt in the name of the state, to the use of the university, in any court having competent jurisdiction; in which action the defendant may be held to bail, of right and without affidavit; and it shall be the duty of the attorney-general or circuit attorney of the district in which any person so offending may be found, immediately upon information given of such offenses to commence and prosecute an action as aforesaid.”

Slaves are real estate in this and other states, and wisdom would dictate great care among the branches of the Church of Christ on this subject. So long as we have no special rule in the Church, as to people of color, let prudence guide, and while they, as well as we, are in the hands of a merciful God, we say: Shun every appearance of evil.

The article is little more than a cautionary reprinting of Missouri statutes requiring African Americans to bring legal documents attesting to their citizenship. But it reflects the fact that the LDS Church had in the 1830s no specific commitment—“no special rule”—to the welfare of Black converts, slave or free. Moreover, its language—“they, as well as we, are in the hands of a merciful God”—indicates that the writer assumed that the readers of the Evening and Morning Star were not African American but white and would see African Americans as a differentiated group. Were African American converts to seek to join the community at Independence, the article seems to make clear, they would do so at their own risk. Empathy they could count on, perhaps, but not solidarity—not even from their own coreligionists. In the matter of slavery and emancipation, the message was clear: Black Mormons could not count on white Mormons in Missouri to bear their burdens. But even this discouragement was not enough to satisfy vigilantes who persisted in seeing the Mormons as an insurrectionary threat. Two days later Phelps printed an “extra” broadside to clarify and amplify the fact that he did in fact intend the article to discourage Black conversion. Still, townspeople organized to destroy the Phelps press, office, and home, and tarred and feathered two local LDS leaders.

What flashes up at this early moment in Mormon history is a dynamic that would take hold as Mormonism institutionalized: when predominantly white Mormon communities found themselves under pressure, at key decision-making nodes, they would elect, as had W. W. Phelps in Independence, to choose their relationships with other whites in positions of power over loyalty to or solidarity with Black people. If there was a logic in these decisions, it was that Mormonism had more to gain through collaboration with whites, even if that came at the expense of Black lives, Black equality, and white integrity. This meant that from its early decades, even when the Church had no official position on slavery and emancipation and comfortably accommodated a range of individual perspectives, it created an environment of conditional welcome that put the burden on Black people like Walker Lewis of making themselves feel at home in “Zion.” Even in settlements like Nauvoo, located in the nominally “free” state of Illinois, Mormon communities were by no means utopian spaces for African Americans. Especially after the death of Joseph Smith in 1844, African American men especially experienced increasingly tenuous circumstances.8 These facts are especially jarring given the early Mormon movement’s professed commitment to establishing community.

Nor did the Black Mormon pioneers, free and unfree, who crossed the plains to Utah in 1847 and years following, find their situation there substantially improved. Utah took up the question of African American citizenship soon after it obtained territorial status in September 1850. On January 5, 1852, Brigham Young said in a prepared speech to the territorial legislature, later published in the Deseret News: “No property can or should be recognized as existing in slaves.”9 Just two weeks later, though, Young declared himself a “firm believer in slavery” and urged passage of “An Act in Relation to Service,” which legalized a form of slavery in Utah that would persist until at least 1862, if not longer. After some debate, the measure was signed into law on February 4, 1852.10 Historians Chris Rich, Nathaniel Ricks, Newell Bringhurst, and Matthew Harris have agreed that one significant factor in the passage of the act was regard for slaveowners and proslavery men who held positions of power in early Utah and desire to protect their interests by establishing what was at least on paper an ameliorated form of slavery to be called “servitude.” Orson Hyde stated so much in the Millennial Star on February 15, 1851:

We feel it to be our duty to define our position in relation to the subject of slavery. There are several in the Valley of the Salt Lake from the Southern States, who have their slaves with them. There is no law in Utah to authorize slavery, neither any to prohibit it. If the slave is disposed to leave his master, no power exists there, either legal or moral, that will prevent him. But if the slave chooses to remain with his master, none are allowed to interfere between the master and the slave. All the slaves that are there appear to be perfectly contented and satisfied. When a man in the Southern states embraces our faith, the Church says to him, if your slaves wish to remain with you, and to go with you, put them not away; but if they choose to leave you, or are not satisfied to remain with you, it is for you to sell them, or let them go free, as your own conscience may direct you. The Church, on this point, assumes not the responsibility to direct. The laws of the land recognize slavery, we do not wish to oppose the laws of the country. If there is sin in selling a slave, let the individual who sells him bear that sin, and not the Church. Wisdom and prudence dictate to us, this position, and we trust our position will henceforth be understood.11

First among the rationale provided by Hyde was consideration for white LDS Church members who brought their slaves with them to Utah. The number of slaves brought to Utah was not large—the 1850 census counted twenty-six and the 1860 census counted thirty, though this number is largely regarded as an undercount. Newell Bringhurst estimated that twelve Mormon migrants to Utah brought a total of “sixty to seventy” slaves, and that early Utah’s slaveholders held positions of influence: Charles C. Rich was one of the Twelve Apostles; William Hooper became Utah’s representative to Congress; Abraham Smoot became mayor of Salt Lake City and Provo. Slaveholders’ investment—economic, political, and social—was noted and regarded by Young, who pledged not to contest it.12 In addition to consideration for the property interests of influential slaveholders, historians have identified other factors as well that made the act something of a “practical compromise,” as Chris Rich described it, that would help Utah avoid becoming embroiled in national controversy, limit large-scale slaveholding in the territory, and signal that white Mormons belonged in the mainstream of American society.13 “Young was not simply negatively situating blacks within Mormon theology,” Paul Reeve explains, “he was attempting to situate whites more positively within American society.”14

Documentary evidence supports an even stronger reading of Brigham Young’s switch on slavery. Young’s own writing reveals that it was his goal as territorial governor and LDS Church president to use territorial laws and LDS Church policies to build a domain where white men would “rule.” I use this word deliberately, as did Brigham Young. It derives in Young’s usage from Genesis 4:7, wherein God tells Abel that he will “rule over” his brother Cain as a consequence of Cain’s faulty sacrificial offering. Young uses this language repeatedly in his private writings and public speeches in early 1852. His manuscript history (a record compiled by clerks from extant papers) entry for January 5, 1852, reads:

The negro . . . should serve the seed of Abraham; he should not be a ruler, nor vote for men to rule over me nor my brethren. The Constitution of Deseret is silent upon this, we meant it should be so. The seed of Canaan cannot hold any office, civil or ecclesiastical. . . . The decree of God that Canaan should be a servant of servants unto his brethren (i.e. Shem and Japhet [sic]) is in full force. The day will come when the seed of Canaan will be redeemed and have all the blessings their brethren enjoy. Any person that mingles his seed with the seed of Canaan forfeits the right to rule and all the blessings of the Priesthood of God; and unless his blood were spilled and that of his offspring he nor they could not be saved until the posterity of Canaan are redeemed.15

He had presented a similar argument, as Jonathan Stapley has shown, as early as February 1849 in Nauvoo. At that time, Young instructed LDS Church leaders that Cain’s attempt to cut off Abel and his posterity from the family of mankind was to be answered by exclusion of Cain and his posterity from the cosmological family of God. “Black Mormon men and women,” historian Jonathan Stapley explains, were according to Young “not to be integrated into the material family of God.”16 Establishment of a territorial theocracy allowed Young to institutionalize this perspective in both governmental and ecclesiastical affairs. In no matter, political or religious, were African Americans as the “posterity” of Cain to “bear rule” over others.

His sentiment was shared widely. Days later, Eliza R. Snow, who was a spouse of Brigham Young, published “The New Year, 1852” on the front page of the Deseret News on January 10, 1852. The poem celebrates the establishment of a theocratic Utah territory and defines Utah in opposition to political currents in the United States, particularly its reform movements:

On, on

Still moves the billowy tide of change, that in

Its destination will o’erwhelm the mass

Of the degen’rate governments of earth,

And introduce Messiah’s peaceful reign.

There is “a fearful looking for,” a vague

Presentiment of something near at hand—

A feeling of portentousness that steals

Upon the hearts of multitudes, who see

Disorder reigning through all ranks of life.

Reformers and reforms now in our own

United States, clashing tornado-like,

Are threat’ning dissolution all around.

Snow wrote disparagingly of anti-slavery reform, holding to Young’s vision of African Americans as “cursed” to “servitude”, as shown in Figure 2.1:

Slavery and anti-slavery! What a strife!

“Japhet shall dwell within the tents of Shem,

And Ham shall be his servant”; long ago

The prophet said: ‘Tis being now fulfill’d.

The curse of the Almighty rests upon

The colored race: In his own time, by his

Own means, not yours, that curse will be remov’d.

Similarly, she dismissed the quest for suffrage:

And woman too aspires for something, and

She knows not what; which if attain’d would prove,

Her very wishes would not be her wish.

Sun, moon, and stars, and vagrant comets too,

Leaving their orbits, ranging side by side,

Contending for prerogatives, as well

Might seek to change the laws that govern them,

As woman to transcend the sphere which God

Thro’ disobedience has assigned to her;

And seek and claim equality with man.

Snow argued that political reform efforts were pointless because the only true government, the “perfect government,” was priesthood:

Can ships at sea be guided without helm?

Boats without oars? steam-engines without steam?

The mason work without a trowel? Can

The painter work without a brush, or the

Shoe-maker without awls? The hatter work

Without a block? The blacksmith without sledge

Or anvil? Just as well as men reform

And regulate society without

The Holy Priesthood’s pow’r. Who can describe

The heav’nly order who have not the right,

Like Abra’m, Moses, and Elijah, to

Converse with God, and be instructed thro’

The Urim and the Thummim as of old?

Hearken, all ye inhabitants of earth!

All ye philanthropists who struggle to

Correct the evils of society!

You’ve neither rule or plummet.

Here are men

Cloth’d with the everlasting Priesthood: men

Full of the Holy Ghost, and authoriz’d

To ‘stablish righteousness—to plant the seed

Of pure religion, and restore again

A perfect form of government to earth.

That form of government was not only to be established in the stakes of Zion, as later generations of Latter-day Saints would come to understand it, but also on earth in the territory of Utah. She makes this point in the Deseret News by repeatedly declaiming at line-break points of poetic emphasis the word “here”:

If elsewhere men are so degenerate

That women dare compete with them, and stand

In bold comparison: let them come here;

And here be taught the principles of life

And exaltation.

Let those fair champions of “female rights”

Female conventionists, come here. Yes, in

These mountain vales; chas’d from the world, of whom

It “was not worthy” here are noble men

Whom they’ll be proud t’ acknowledge to be far

Their own superiors, and feel no need

Of being Congressmen; for here the laws

And Constitution our forefathers fram’d

Are honor’d and respected. Virtue finds

Protection ‘neath the heav’n-wrought banner here.

‘Tis here that vile, foul-hearted wretches learn

That truth cannot be purchas’d—justice brib’d;

And taught to fear the bullet’s warm embrace,

Thro’ their fond love of life, from crime desist,

And seek a refuge in the States, where weight

Of purse is weight of character, that stamps

The impress of respectability.

“Knowledge is pow’r.” Ye saints of Latter-day!

You hold the keys of knowledge. ‘Tis for you

To act the most conspic’ous and the most

Important parts connected with the scenes

Of this New Year: To ‘stablish on the earth

The principles of Justice, Equity,—

Of Righteousness and everlasting Peace.17

As Maureen Ursenbach Beecher wrote, “Eliza adopted ideas from whatever source she trusted—Joseph Smith’s utterances would be received without question—and worked them meticulously into a neatly-packaged theology with the ends tucked in and the strings tied tight.”18 Eliza R. Snow endorsed Brigham Young’s vision of a theocratic Utah governed by white priesthood holders.

Figure 2.1. Excerpt from Eliza R. Snow, “The New Year,” published page 1, Deseret News, January 10, 1852.

Image courtesy of Marriott Special Collections Library, University of Utah.

We see this explicit conjoining of Church and territory on February 5, 1852, the day after the passage of the “Act in Relation to Service” and the day the legislature established voting rights (white men only) in Cedar City and Fillmore. Young used the occasion to hold forth extemporaneously and at length on the status of whites, Blacks, and others in matters spiritual and temporal. Records from this day are the first contemporary document of a theologically rationalized ban on full participation by Black Africans and African Americans. Young declared that African Americans were descendants of Cain and thus bearers of a curse that prohibited them from holding the priesthood. Further, he stated that any who intermarried with African Americans would bear the same curse and that it would be a blessing to them to be killed. Finally, he outlined principles for establishing the “Church” as the “kingdom of God on the earth,” returning again and again to the ideal of white “rule” as he had in his January 5 journal entry:

I know that they cannot bear rule in the preisthood, for the curse on them was to remain upon them, until the resedue of the posterity of Michal and his wife receive the blessings. . . . Now then in the kingdom of God on the earth, a man who has has the Affrican blood in him cannot hold one jot nor tittle of preisthood; . . . In the kingdom of God on the earth the Affricans cannot hold one partical of power in Government. . . . The men bearing rule; not one of the children of old Cain, have one partical of right to bear Rule in Government affairs from first to last, they have no business there. this privilege was taken from them by there own transgressions, and I cannot help it; and should you or I bear rule we ought to do it with dignity and honour before God. . . . Therefore I will not consent for one moment to have an african dictate me or any Bren. with regard to Church or State Government. I may vary in my veiwes from others, and they may think I am foolish in the things I have spoken, and think that they know more than I do, but I know I know more than they do. If the Affricans cannot bear rule in the Church of God, what business have they to bear rule in the State and Government affairs of this Territory or any others? . . . If we suffer the Devil to rule over us we shall not accomplish any good. I want the Lord to rule, and be our Governor and dictater, and we are the boys to execute. . . . Consequently I will not consent for a moment to have the Children of Cain rule me nor my Bren. No, it is not right. . . . No man can vote for me or my Bren. in this Territory who has not the privilege of acting in Church affairs.

Shorthand Pitman transcriptions of the speech provide an even stronger sense of Brigham Young’s perspective:

I tell you this people that commonly called Negros are children of Cain I know they are I know they cannot bear rule in priesthood first sense of word for the curse upon them was to continue on them was to remain until the residue of posterity of [Adam] and his wife receive the blessings they should bear rule and hold the keys of priesthood until times of restitution come . . . in kingdom of God on earth a man who has the African blood in him cannot hold one one jot nor tittle of priesthood now I ask for what for upon earth they was the true eternal principles Lord Almighty has ordained who can help it angels cannot all powers cannot take away the eternal I Am what I Am I take it off at my pleasure and not one particle of power can that posterity of Cain have until the time comes the Lord says have it that time will come. . . . In the kingdom of God on the earth the Africans cannot hold one particle of power in government they are the subjects the eternal servants of residue of children and the residue of children through the benign influence of the Spirit of the Lord have the privilege of saying to posterity of Cain inasmuch as the Lord [is?] will you may receive the Spirit of Lord by baptism that is the end of their privilege and no power on earth give them any more power . . . let my seed mingle with seed of Cain brings the curse upon me and my generations reap the same rewards as Cain in the priesthood tell you what it do if he were to mingle their seed with the seed of Cain bring not only curse upon them selves but entail it on their children get rid of it . . . again to the principle of men bearing rule not one of children of old Cain as any right to bear rule in government affairs from first to last no business there it was taken from them by their own transgression and I and I cannot help it and you and I bear rule or do with dignity before God I am [as] much opposed to the principle of slavery as any man because it is an abuse I am opposed to abusing that which God has decreed and take a blessing and make a curse of it greatest blessings to all the seed of Adam to have seed of Cain for servants those that serve who use them with all the heart the feeling use their children and their compassion should reach over them around them and treat them as kindly as mortal beings can be and their blessings in life great in proportion than those provide bread and dinner for them. . . . I will not consent for one moment to have an African to dictate me nor my brethren with regard church and state government I may vary from others and they may think I [am] foolish and short sighted who think they know more than I do I know I know more than they do consequently if they cannot bear rule in church of God what business have they in bearing rule in state and government affairs of territory of those whose by right God should reign the nations of earth should control kings. . . . I will not consent for a moment to have the children of Cain rule me nor my brethren when it is not right. Why not say some thing of this in constitution allow me the privilege to tell it right out it is not any of their damned business what we do so we do not say anything about and it is for them to sanction and it is for us to say what we will about it it is written right out that every male citizen. . . . I have given you the true principles and doctrine no man can vote for me my brethren in territory has not the privilege of voting acting in church affairs.19

Brigham Young’s white supremacy was posited primarily but not exclusively in relation to African Americans. In the same speech, Brigham Young envisioned a day when people might emigrate to Utah from the “Islands,” or “Japan,” or “China.” They too, Young averred, would have no understanding of government and would have to be governed by white men.20 This speech suggests that the legalization of slavery and Young’s exclusion of Blacks from the priesthood were elements of a larger vision in which the Kingdom of God on earth was to be established with whites avoiding intermixture with Blacks except so as to rule over them.

The legal establishment of Black servitude in Utah territory managed to preserve the slaveholding interests of a few influential white Mormons while discouraging voluntary emigration to Utah territory by free Blacks, even as free Blacks were setting out to seek their fortunes in other western states. In December 1852, Young told the legislature that the act “had nearly freed the territory of the colored population.”21 The 1860 census found 59 African Americans in Utah, constituting .14% of the territorial population. In neighboring Nevada, the census found 45 African Americans constituting .6% of the territorial population, and in California, 4,086 African Americans constituting 1.1% of the population.22

One of the consequences of “freeing the territory” was eliminating the possibility that white Mormon people would interact with African Americans as neighbors, coworkers, friends, or coreligionists. The limited extent of Black servitude also “freed” white Mormons from engaging to any significant extent with the national controversy over slavery’s abolition. Outsiders who visited Salt Lake City were struck by white Mormons’ lack of engagement with the issue. B. H. Roberts’s History of the Church commemorates the lack of abolitionist sentiment in Utah, as noted by Horace Greeley at the Salt Lake City banquet in his honor in 1859:

I have not heard tonight, and I think I never heard from the lips or journals of any of your people, one word in reprehension of that national crime and scandal, American chattel slavery, this obstinate silence, this seeming indifference on your part, reflects no credit on your faith and morals, and I trust they will not be persisted in.23

Greeley wondered at the “obstinate silence” and “seeming indifference” of white Mormons. But he misunderstood. Silence did not mean white Mormons were indifferent on race. The legal and theological architects of “the Kingdom of God on earth” had established Utah territory as a white supremacist space. Brigham Young used his conjoint role as LDS Church president, territorial governor, and empire builder to implement anti-Black racism as a means of consolidating relationships among the young territory’s key operatives and as a foundational step toward realizing a theocratic Mormon kingdom where white men “ruled.”

Two years after the death of Brigham Young, in May 1879, LDS Church President John Taylor traveled to a conference of the Utah Valley Stake in Provo. Presiding over the stake was Abraham O. Smoot. Smoot had a long history of close connection with Brigham Young. After his conversion in Kentucky in 1833, Smoot proved himself a loyal, strong-tempered, battle-ready defender of the Mormon movement, fighting in 1838 alongside Porter Rockwell among the Danites, and serving as a Nauvoo policeman. He migrated with his wife Margaret to Utah in 1847 as the leader of two companies of fifty; subsequently, Smoot captained three additional companies in 1850, 1852, and 1856, and served as well a number of foreign missions. Brigham Young acknowledged his leadership by appointing him superintendent of one of the valley’s first sugar factories and bishop of the Sugar House ward, which set Smoot on a path to become alderman from the Sugar House district of Salt Lake, and then mayor of Salt Lake City from 1857 to 1866. It was Smoot who, in July 1857, discovered with Porter Rockwell the advance of US Army troops toward Utah and turned around from Missouri to ride back to Utah and personally warn Brigham Young. In 1868, at the instruction of Brigham Young, Smoot moved to Provo, where he became the region’s effective governor—simultaneously serving as Provo city mayor (1868–1881), Utah Valley stake president (1868–1881), and the first head of the Board of Trustees of Brigham Young University. Smoot played an elemental role in the creation and consolidation of key LDS institutions and in Utah’s early theocracy.24

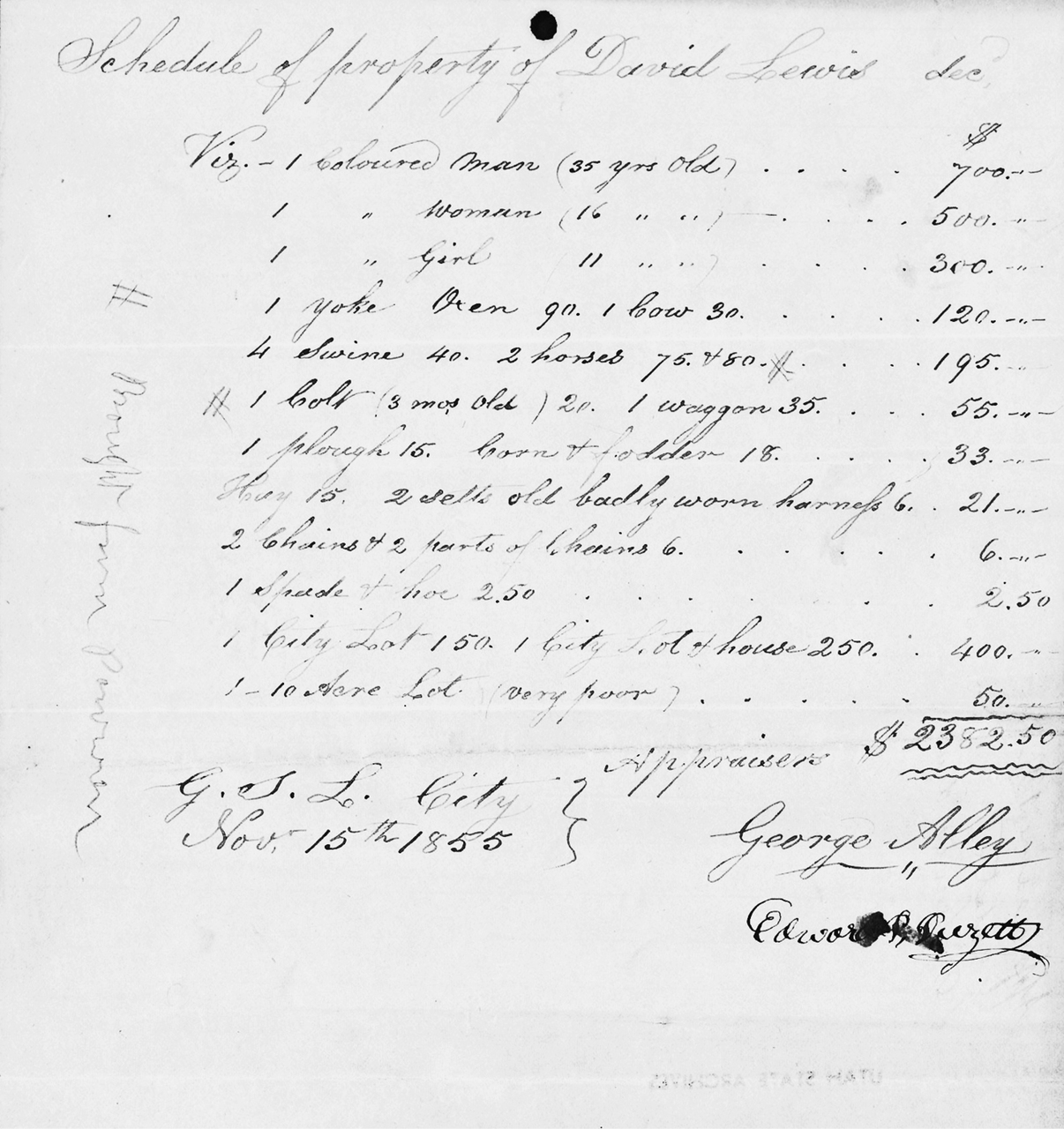

Smoot was also a solid proponent of slavery. As a missionary in Alabama in 1844, he refused to distribute political literature for Joseph Smith’s 1844 presidential campaign that proposed a gradual emancipation plan. After his move to Utah, historian Amy Tanner Thiriot has confirmed, Smoot owned or hired three slaves. The 1851 census slave schedule held in draft form at the Church History Library shows Abraham and Margaret Smoot in possession of a slave named Lucy; the Great Salt Lake County 1860 census schedule of “Slave Inhabitants” shows “A. O. Smoot” as being in possession of two male slaves, both aged forty.25 One of these was a man named Jerry who had been the property of David and Duritha Trail Lewis, fellow Kentucky-born converts to the Church. Jerry came to Utah in the company of migrants led by David Lewis in 1851.26 He remained with the family after David’s death in 1855, on November 2, when (as figure 2.2 shows) the Third District Court in Salt Lake County recorded three individuals among the “property” of the deceased:

1 coloured man (35 years old) . . . $700

1 “ woman (16 years old) $500

1 “ girl (11 years old) $30027

Figure 2.2. Probate records of David Lewis.

Image courtesy of Utah Department of Administrative Services, Division of Archives & Records Service.

On August 4, 1858, Duritha filed a record with the clerk of the Third Judicial District Court for the Utah territory registering these same individuals as her property:

Duritha Lewis who being duly sworn, states on oath that she is the true and lawful owner of three persons of African blood, whose names and ages are as follows to wit; Jerry, Caroline, and Tampian, aged 38, 18, 14. That she said Duritha Lewis inherited them from her father Solomon Trail according to the laws of the state of Kentucky. That by virtue of such inheritance, she is entitled to the services of the said, Jerry, Caroline, and Tampian, during their lives, according to the Lewis of the said Territory. That she makes this affidavit that they may be registered as slaves according to the requirements, of the said Lewis of the said Territory, for life.28

As a widower who had initially been remarried but left that household, Duritha Trail Lewis was in a vulnerable economic position. On January 3, 1860, Brigham Young wrote to Duritha Lewis to encourage her to sell Jerry:

Dear Sister Lewis:

I understand that you are frequently importuned to sell your negro man Jerry, but that he is industrious and faithful, and desires to remain in this territory: Under these circumstances I should certainly deem it most advisable for you to keep him, but should you at any time conclude otherwise and determine to sell him, ordinary kindness would require that you should sell him to some kind faithful member of the church, that he may have a fair opportunity for doing all the good he desires to do or is capable of doing. I have been told that he is about forty years old, if so, it is not presumable that you will, in case of sale, ask so high a price as you might expect for a younger person. If the price is sufficiently moderate, I may conclude to purchase him and set him at liberty.

Your brother in the gospel, Brigham Young.29

Young’s letter is revealing in many respects. First, in noting that Duritha was “frequently importuned” to sell Jerry in Salt Lake City, it suggests that demand for slaves was greater than supply in Utah territory. Second, it documents that Brigham Young was personally involved in exchanges or trades of slaves: he prevailed upon Duritha Lewis to advise her on the desirability of sale, to set pricing expectations, and to encourage her to sell him to another Church member. Although Young offered to “purchase him and set him at liberty,” presumably at a cost discounted from his $700 valuation in 1855, this sale never materialized. Instead, by June 1, 1860, Jerry (along with one other forty-year-old Black man) was in the possession of Abraham Smoot. Both were presumably freed in 1862, though Jerry moved with the Smoot household to Provo in 1868.

Smoot was a talented entrepreneur whose enterprises included farming and ranching collectives, the first woolen mills in Utah, lumber mills and lumber yards, and banks. He amassed a substantial fortune that he used at the end of his life to build the Provo Tabernacle and to pay the substantial debts of Brigham Young University, making him its first underwriter. It is unlikely that his few slaves held from the 1850s through 1862 played a substantial role in the growth of these industries or Smoot’s wealth. However, it is clear that they played a significant symbolic and ornamental role for Smoot, who as a native Kentuckian and pro-slavery advocate likely viewed slaveholding as an appropriate and necessary status marker for a man of means. Black lives were, to Abraham Smoot, a display of wealth.

After the Saturday morning session of the Utah Valley stake conference, Smoot brought back to one of his four Provo homes President John Taylor, Taylor’s secretary John Nuttall, Brigham Young Jr., and Zebedee Coltrin. Coltrin, who had joined the Church in 1831, attended the first School of the Prophets in 1833, emigrated to Utah in 1847, lived in Spanish Fork, and was a member of Smoot’s stake. Taylor sought from both men their understanding of Joseph Smith’s views on race in connection with a request from Elijah Abel to be sealed in the temple to his spouse. As notes taken by John Nuttall document, Taylor first interviewed Coltrin, who stated that in 1834 Joseph Smith told him “the negro has no right nor cannot hold the Priesthood” and that Abel had been ordained to the Seventy as symbolic compensation for labor on the temple but dropped when his “lineage” was subsequently discovered. Coltrin also testified that he had experienced a deep sense of revulsion while ordaining Abel at Kirtland. Smoot spoke next, indicating that he agreed with Coltrin’s statement and providing as additional evidence that Black men should not receive the priesthood his memory when serving a mission in the southern states in 1835–1836 that Joseph Smith had instructed him to neither baptize nor ordain slaves.30 Having traded for and hired Black men, Smoot understood the legal and social distinctions between free and enslaved Black men, but he did not maintain these differences in the testimony he provided to President Taylor, advancing Joseph Smith’s instructions in regard to conversion of slaves—a sensitive issue given the long and complicated history in the United States of proselyting and religious instruction of slaves, compounded by rumors in border and southern states that Mormons might seek to foment slave revolt—as though they were to pertain to Black men at large.

Smoot and Coltrin did not provide correct testimony. Elijah Abel himself held and provided Church leaders with documentary evidence of his ordination as an elder on March 3, 1836, a fact reaffirmed in his patriarchal blessing, given by Joseph Smith Sr. He also owned and provided evidence of his ordination to the Third Quorum of the Seventy in the Kirtland Temple on December 20, 1836, which was commemorated in two certificates affirming his membership in the quorum in the 1840s and 1850s. In fact, just a few months before the interview at Abraham Smoot’s house, on March 5, 1879, as historian Paul Reeve has discovered, Abel spoke and shared his recollections of Joseph Smith at a meeting of the Quorums of the Seventies at the Council House in Salt Lake City.31 In the face of Abel’s open, ongoing, and uncontested participation in LDS leadership, Smoot and Coltrin’s testimony was bold, controversial, and socially violent. Even more striking is the fact that both Coltrin and Smoot were contemporaneous, living witnesses to Elijah Abel’s ordination to the Third Quorum of the Seventy on December 20, 1836, in Kirtland. It was, in fact, Zebedee Coltrin himself who had ordained Abel, as records show, along with six other new members of the Third Quorum of the Seventy—including Abraham Smoot, that very same day in that same place.32

It appears that Smoot and Coltrin jointly agreed to arrange their recollections to support a position opposing Black ordination and temple participation. They did so even though they themselves had been primary witnesses to Abel’s ordination: Coltrin performed it, and Smoot was certainly present at the occasion and may have witnessed the actual ceremony. Both men withheld this vital testimony from President Taylor. Both men instead purposefully provided testimony that obscured the ordination, obscured vital differences between slave and free, and attributed an anti-ordination stance to Joseph Smith himself. Abraham Smoot and Zebedee Coltrin together bore false witness to bar full participation by Black men in the priesthood and temple ceremonies.

How do we understand what happened at the home of Abraham Smoot that day? How do we understand the dynamics that led both Coltrin and Smoot to arrange their testimonies to align and to obscure important facts in order to advance Black exclusion? It would be perfectly human for Abraham Smoot to allow his own views on the status of African Americans, views that had been fully supported by President Brigham Young who helped broker Smoot’s purchase of one of his slaves, to influence him. He would have felt justified in doing so not only by the personal support of Brigham Young but also by the culture of theocratic expediency in which he had risen to power, and by the near-complete absence of a culture of white abolitionism or emancipation in Utah in the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s. He would have felt completely assured, in the majority, and in the right, advancing his interest in Black exclusion. Zebedee Coltrin never owned slaves. In fact, after settling in Spanish Fork in 1852 and surviving three subsequent years of failed crops, his family had survived on pigweed and the food carried to them by a Black slave belonging to the Redd family—likely Marina Redd. Poverty had been a persistent feature of Coltrin’s postemigration life. When Brigham Young instructed Abraham Smoot to organize the United Order in Spanish Fork in 1873, Zebedee Coltrin was among those who joined, and even though he was not among those Smoot put forward as its slate of officers on May 2, 1874, Coltrin vocally encouraged his fellow high priests in Spanish Fork to deed their property to the order—as he had in all likelihood done himself. Smoot presided over the United Order and held the deeds to land, including the land on which Zebedee Coltrin’s land and home stood.33 Had he wanted to enlist Coltrin’s loyalties, to arrange their joint recollections to support Black exclusion, had he wanted to steer the meeting—held at his own home, with his own testimony to close—Smoot was certainly in a position to do so. He effectively owned Coltrin’s land, home, and life chances. And it would have been in his best economic and social interests for Coltrin to comply. In fact, to resist the implicit and explicit pressure of the situation, Coltrin would have to have been a man of exceptional clarity, resolve, and independence. The very nature of the testimony he provided that day does not suggest this was the case.

Additional insights are provided from the surviving text of Coltrin’s recollections, as documented in Nuttall’s journal. Coltrin recalled that he had always opposed the ordination of Black men, and that upon return from the Zion’s Camp expedition, in 1834, he had put the question directly to Joseph Smith: “When we got home to Kirtland, we both went into Bro Joseph’s office together . . . and [Brother Green] reported to Bro Joseph that I had said that the Negro could not hold the priesthood—Bro Joseph kind of dropt his head and rested it on his hand for a minute. And said Bro Zebedee is right, for the Spirit of the Lord saith the Negro had no right nor cannot hold the Priesthood.” As recollected by Coltrin, the story is arranged to feature Coltrin’s primary connection with Joseph Smith, to highlight his own advance discernment of prophetic revelation, and to ascribe to Joseph Smith an affirmation of “Bro Zebedee’s” “rightness.” Relationship, discernment, and rightness have been among the most powerful forms of social capital in Mormonism, and Coltrin arranged his recollections to claim all three for himself. His memory of Smith having “dropt his head” also suggests a micropolitics of fealty. Coltrin also claimed to have heard Smith announce in public that “no person having the least particle of Negro blood can hold the priesthood.”34 The word “particle” can actually be traced to various speeches of Brigham Young on the question of Black ordination. Coltrin demonstrated his own fealty to Young by putting his words in the mouth of Joseph Smith in the presence of Young’s son Brigham Young Jr. and his successor John Taylor. Coltrin, who, despite his ordination to Church patriarch in 1873, had become a minor player in the affairs of the Church due in part to his financial and geographical marginalization in Spanish Fork, enjoyed something of a personal renaissance after this interview, as he was invited by John Taylor to accompany him to temple dedications in his official capacity as patriarch in years following. Relationship, discernment, rightness, and loyalty or fealty shaped this pivotal moment in LDS history. The joint witness provided by Smoot and Coltrin, the consensus of two white men, was believed over documentation provided by a single Black man, Elijah Abel. Especially after the death of Elijah Abel in 1884, the Smoot-Coltrin consensus came to serve as a basis for LDS Church policy.

These three key points in early Mormon history present micropolitical instances when white Mormons opted to build the Mormon movement, Utah territory, and LDS Church priesthood by preferring relationships among whites over a sense of obligation to the human rights of Blacks, Black enfranchisement, and the lived reality of Black testimony. Nineteenth-century Mormons, as historian Paul Reeve has convincingly shown, were on the “wrong side of white”: repeatedly racialized and marginalized in popular opinion, in the press, and by political and legal institutions.35 Building the movement and securing a space for the free exercise of our religion required tactical concessions and agreements, and in the absence of a strongly developed, even singular religious commitment to Black emancipation, it was in every respect expedient to operationalize a variety of white privilege and pass as white. This desire for the protections and privileges of whiteness created a climate generally unwelcoming to African Americans, which thus reinscribed white supremacy by “freeing” white Mormons of lived relationships with and accountability to Black fellow Saints and neighbors.

White Mormons in key decision-making roles actively and intentionally privileged white relationships, loyalty, solidarity, and “rule” over Black lives and Black testimonies at the expense of theology, integrity, and ethics but to the benefit of institutional growth and dominion. This is the definition of white supremacy. White supremacy guided the formation of key LDS institutions—the theocratic territory of Utah, the modern correlated orders of the priesthood, even Brigham Young University, whose founding trustee and major funder bore false witness and influenced others to do the same to block Black Mormons from full access to priesthood and temple rites. At each instance, we witness intentional human decisions to advance white over black.

Thus we find at work at formative nodes in Mormon history an anti-Black racism differentiated from the anti-Black racism of the American South by important distinctions in economic, cultural, and religious contexts, but one just as intense and pervasive.36 Did Black lives matter in early Mormon Utah? Even before the full consolidation and institutionalization of the anti-Black priesthood and temple ban, stories flashing up at the joints of history suggest that they did not. They reveal, in fact, an active toleration and even celebration of anti-Black violence. Robert Dockery Covington, the leader of the “Cotton Mission” organized by Brigham Young in 1857 to establish a cotton industry in southern Utah and an LDS bishop, recounted to fellow settlers (according to a contemporaneous record) stories of his physical and sexual abuse (including rape) of African American men, women, and children. His statue stands today in downtown Washington, Utah, and the name of Dixie College in St. George commemorates the area’s ties to the American South.37 In 1863, Brigham Young preached at the Tabernacle on Temple Square in Salt Lake City that intermarriage between blacks and whites was forbidden by God on penalty of blood atonement—death. Declaring himself opposed to both slavery as practiced in the South and its abolition, Young declared: “The Southerners make the negroes and the Northerners worship them.”38 In December 1866, Thomas Coleman, an African American man, was found murdered in Salt Lake City—stabbed and his throat cut, a method of killing resembling “penalties” affixed in early Mormon temple rituals. An anti-miscegenation warning was inscribed on a sheet of paper and “attached” to his corpse, as reported by the Salt Lake Daily Telegraph on December 12.

There are, of course, other instances in LDS history when even Church members who were deeply embedded in Mormonism’s theocratic contexts raised a voice of conscience to oppose anti-Black racism and white supremacy. On January 27, 1852, Orson Pratt raised a voice of opposition to Brigham Young and the “Act in Relation to Service.” In this speech, which survives only in shorthand, Pratt refused to allow that slavery or any other oppression of Black people was authorized by God’s curse on Cain. “Shall we assume the right without the voice of Lord speaking to us and commanding us to [allow] slavery into our territory?” he asked. Refusing slavery “would give us a greater influence among the other nations of earth and by that means save them. . . . I look for the welfare of nations abroad who will never hear the gospel of Jesus Christ if we make a law upon this subject . . . for us to bind the African because he is different from us in color enough to cause the angels in heaven to blush.”39 Pratt had felt the pressure to accede to Church leadership time and time again—even in so tender a circumstance as being pressured by Joseph Smith to reject the testimony of Pratt’s wife that Smith had sought to marry her. But he had told Brigham Young in December 1847 during an argument over the relationship of the president of the Church to the Quorum of the Twelve:

I av remarked we av hitherto acted too much as machines[,] heretofore—instead of as councillors—[A]s to following the Sp[irit, we have been machines. T]hat is what I believe in. . . . I will confess to my own shame I av decided contrary to my own feelings many times. I av been too much a machine—[B]ut I mean hereafter not to demean myself as to let my feelings run contra[ry] to my own judg[men]t.

On the issue of anti-Black racism, Orson Pratt refused to be a “machine.” He sided with conscience, and he continued to do so, even when his exhortations failed, when he on February 5, 1852, voted against the bills for the incorporation of Fillmore and Cedar City, which prohibited Black franchise.40 Pratt’s is just one example that shows that at every decisive micropolitical moment in Mormon history it would have been possible to do differently on matters of race. But as we established the foundational institutions of our religion, white Mormons did not choose that path. Neither, really, did any predominantly white American Christian institution.

1.Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White (New York: Verso, 1995); Karen Brodkin, How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says About Race in America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998).

2.George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit From Identity Politics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), vii.

3.Max Mueller, Race and the Making of the Mormon People (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

4.Matthew L. Harris and Newell G. Bringhurst, eds., The Mormon Church and Blacks: A Documentary History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015), 29. See also Martin B. Hickman, “The Political Legacy of Joseph Smith,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 3.3 (1968): 23; Richard D. Poll and Martin Hickman, “Joseph Smith's Presidential Platform,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 3.3 (1968): 19–23.

5.On Lewis, see James Oliver Horton, “Generations of Protest: Black Families and Social Reform in Ante-Bellum Boston,” New England Quarterly 49.2 (1976): 242–256; Connell O'Donovan, “The Mormon Priesthood Ban and Elder Q. Walker Lewis: ‘An example for his more whiter brethren to follow,’” John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 26 (2006): 48–100.

6.On early Mormonism’s treatment of African Americans, see Lester E. Bush Jr. “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 8:1 (Spring 1973): 225–294; Ronald K. Esplin, “Brigham Young and Priesthood Denial to the Blacks: An Alternate View,” BYU Studies 19.3 (1979): 394–402; Newell G. Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People within Mormonism (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1981); Newell G. Bringhurst, “The Mormons and Slavery: A Closer Look,” Pacific Historical Review 50.3 (1981): 329–338, www.jstor.org/stable/3639603; Armand Mauss, All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 212–230; Newell G. Bringhurst, “The ‘Missouri Thesis’ Revisited: Early Mormonism, Slavery, and the Status of Black People,” in Black and Mormon, ed. Newell Bringhurst and Darron Smith (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2004), 13–33; Newell G. Bringhurst, “Joseph Smith’s Ambiguous Legacy: Gender, Race, and Ethnicity as Dynamics for Schism Within Mormonism After 1844: 2006 Presidential Address to the John Whitmer Historical Association,” John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 27 (2007): 1–47; Matthew L. Harris and Newell G. Bringhurst, eds., The Mormon Church and Blacks: A Documentary History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015); W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); Max Mueller, Race and the Making of the Mormon People (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Ronald Coleman, “The African-American Pioneer Experience in Utah,” lecture delivered August 30, 2017, Wellsville Historical Society, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=frD1lLeo75A. On estimated counts of early African American LDS Church members, see Reeve, 178.

7.William W. Phelps, “Free People of Color,” Evening and Morning Star 2.14 (1833): 217–218.

8.See, for example, the experience of an African American man named Chism, as described in Bringhurst (1981) and Max Mueller, Race and the Making of the Mormon People (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2017), 132.

9.Bringhurst (1981), 335; Reeve, 149.

10.Harris and Bringhurst, 32–35; Reeve, 148–159; John Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Belknap, 2012), 225–226.

11.Orson Hyde, “Slavery Among the Saints,” The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star 13 (April 15, 1851): 63, http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/MStar/id/2335.

12.See Bringhurst (1981), Nathaniel R. Ricks, “A Peculiar Place for the Peculiar Institution: Slavery and Sovereignty in Early Territorial Utah” (MA thesis, Brigham Young University, 2007); Christopher B. Rich Jr. “The True Policy for Utah: Servitude, Slavery, and ‘An Act in Relation to Service,’” Utah Historical Quarterly 80 (2012): 54–74; Harris and Bringhurst, 32–35.

13.Rich, 55.

14.Reeve, 155.

15.“History of Brigham Young,” entry dated January 5, 1852, in Church Historian’s Office Records Collection, LDS Church Archives; quoted in Ricks, 114.

16.Jonathan Stapley, The Power of Godliness: Mormon Liturgy and Cosmology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 21.

17.E. R. Snow, “The New Year 1852,” Deseret News, January 10, 1852, 1; see also Jill Mulvay Derr and Karen Lynn Davidson, Eliza R. Snow: The Complete Poetry (Salt Lake City: BYU Press, 2009), 419–420.

18.Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, “The Eliza Enigma,” Dialogue 11 (1978): 40–43, http://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V11N01_33.pdf.

19.Church History Department Pitman Shorthand transcriptions, 2013–2017; “The Lost Sermons” publishing project files, 1852–1867; Brigham Young, February 5, 1852; Church History Library, https://catalog.lds.org/record/5df3b7da-d0a5-437b-8268-7dde8a87c76e/comp/fc314280-4158-4286-a6c7-6571eccf11ad?view=browse (accessed March 26, 2019).

20.Brigham Young Addresses, Ms d 1234, Box 48, Folder 3, dated February 5, 1852, located in the LDS Church Historical Department, Salt Lake City, Utah. See also https://archive.org/details/CR100317B0001F0017.

21.Bringhurst (1981), 335; Ricks, 131.

22.The United States Census, US Census, 1860, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1864/dec/1860a.html.

23.B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church, vol. 4 (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1930), 533.

24.C. Elliot Berlin, “Abraham Owen Smoot: Pioneer Mormon Leader” (MA thesis, Brigham Young University, 1955), http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5522&context=etd.

25.Amy Tanner Thiriot, personal correspondence, November 10, 2017; “Schedule” (June 1860), http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~utgenweb/Census/1860US/SaltLake/PageP24.jpg.

26.“David Lewis Company, 1851,” Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel, https://history.lds.org/overlandtravel/companies/185/david-lewis-company.

27.Third District Court, Salt Lake County Probate Case Files, no. 39, “in the Matter of David Lewis” (1855), http://images.archives.utah.gov/cdm/ref/collection/p17010coll30/id/590.

28.Text of statement reprinted in “Duritha Trail Lewis,” Our Family Heritage, July 3, 2011, http://ourfamilyheritage.blogspot.com/2011/07/duritha-trail-lewis.html.

29.Letter reprinted in Margaret Blair Young and Darius Gray, Bound for Canaan (revised and expanded) (Salt Lake City, UT: Zarahemla Books, 2013).

30.Bush (1973), 31–32; Calvin Robert Stephens, “The Life and Contributions of Zebedee Coltrin” (MA thesis, Brigham Young University, 1974), 53n55; Reeve, 196–197.

31.Reeve, 196–197.

32.Stephens, 53–55. See also Paul Reeve, “Guest Post: Newly Discovered Document Provides Dramatic Details About Elijah Able and the Priesthood,” Keepapitchinin, January 18, 2019, http://www.keepapitchinin.org/2019/01/18/guest-post-newly-discovered-document-provides-dramatic-details-about-elijah-able-and-the-priesthood/.

33.Stephens, 77–78, 86–88.

34.Stephens, 55.

35.Reeve, 138.

36.Dennis Lythgoe observed in his 1966 University of Utah MA thesis, “Negro Slavery in Utah,” that the Mormon “position on the Negro closely resembled that of the South” (84).

37.Brian Maffly, “Utah’s Dixie Was Steeped in Slave Culture, Historians Say,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 10, 2012, http://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=55424505&itype=CMSID.

38.Bringhurst and Harris, 43.

39.Margaret Blair Young, “A Few Words From Orson Pratt,” Patheos, June 11, 2014, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/welcometable/2014/06/a-few-words-from-orson-pratt/.

40.Gary James Bergera, “The Orson Pratt—Brigham Young Controversies: Conflict Within the Quorums, 1853–1868,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 13.2 (1980): 7–49; see also Gary James Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum: Orson Pratt, Brigham Young, Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002).