Muhammad’s authority to interpret definitively the meaning of the Quran and instruct Muslims did not disappear when he died. It continued in the form of an inheritance left to the Muslim community. To a large extent, sectarian divisions in Islam have revolved around competing claims over who should assume this role of authoritative interpreter. The tradition that became Sunni Islam offered one answer: the community as a whole, represented by the ulema (the Muslim scholarly class), was heir to Muhammad. Their collective interpretation of Islam, expressed through consensus (ijma’), was as definitive as the Quran or the Prophet’s edicts.

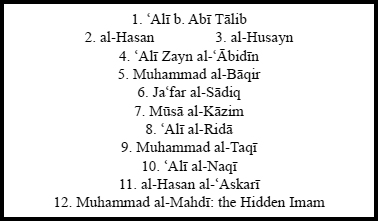

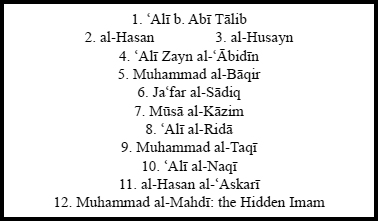

The tradition that would become Shiite Islam proposed a different answer: the family of the Prophet had inherited his authority, which was held by select members of the family known as imams. The first imam was ‘Ali b. Abi Talib (d. 40/660), Muhammad’s cousin and the husband of his daughter Fatima, through whom all descendants of the Prophet trace their ancestry. Shiites maintain that the Prophet had imparted his knowledge to ‘Ali, and through ‘Ali to his descendants. When one of these revered descendants, Musa al-Kazim (d. 183/799), was asked if the Prophet had brought mankind all the knowledge they would require to understand their religion and if any of that had been lost, he replied, ‘No, it is with his family.’1 Musa’s father, Ja‘far al-Sadiq (d. 148/765), had given the same answer. The Quran contains the answers to all questions, he said, ‘but men’s minds cannot grasp them.’ For an imam in whose veins the Prophet’s esoteric knowledge of God’s will runs, however, he can see these answers in the Quran ‘as easily as he looks at his own palm.’2

Hadiths were one medium for transmitting the Prophet’s legacy through the generations of his community as they expanded outwards from Medina in time and space. Since Shiism had a different vision of the heirs to the Prophet’s authority, it is no surprise that the Shiite hadith tradition differs greatly from its Sunni counterpart. As the majority of the world’s Shiites subscribe to the Imami, or Ithna‘ashari (‘Twelver,’ so called because it traces the Prophetic authority through twelve imams) creed, and since Imami hadith scholarship has dwarfed that of other Shiite sects, in this chapter we will focus mainly on the Imami Shiite hadith tradition. We will then turn our attention briefly to Zaydi Shiite hadith scholarship. As in the previous chapters, mention of ‘authentic’ or ‘forged’ hadiths refers to Muslim standards for reliability, not Western historical ones.

In Sunni Islam, hadiths were reports transmitted from the only individual that Sunnis deemed infallible: the Prophet Muhammad. In Imami Shiite Islam, the infallibility of the Prophet lived on in the form of the imams, each one appointing one of his sons as the next imam. Not only were these imams therefore the best source for sayings of the Prophet, they themselves were sources of their own hadiths. The vast majority of Imami Shiite hadiths thus occur in one of three forms:

1 A hadith of the Prophet is transmitted through an isnad made up of the imams after him.

2 The saying of an imam is transmitted from him by later imams.

3 The saying of an imam is transmitted from him via an isnad of his followers.

Figure 4.1 Forms of Imami Shiite Hadiths

Whether a hadith originated with the Prophet or an imam, or whether or not the isnad between an imam and the Prophet was complete was of no importance. After all, imams were infallible and spoke with the inherited authority of the Prophet. A famous Shiite hadith makes this amply clear. The sixth imam, Ja‘far al-Sadiq, is reported to have said:

My hadiths are the hadiths of my father, and the hadiths of my father are the hadiths of my grandfather, and the hadiths of my grandfather are the hadiths of al-Husayn, and the hadiths of al-Husayn are the hadiths of al-Hasan, and the hadiths of al-Hasan are the hadiths of the Commander of the Faithful (‘Ali b. Abi Talib) (s), and the hadiths of the Commander of the Faithful are the hadiths of the Messenger of God (s), and the hadiths of the Messenger of God are the words of God most high.3

Shiites also sometimes narrated hadiths from the Prophet via his Companions in the same manner as Sunnis. But as we will discuss below, this was generally done for polemical purposes. There was little reason for Shiites to rely on the all-too-fallible Companions of the Prophet when they believed that the imams who descended from him were immune to deception or misguidance.

Three major events defined the Imami Shiite community and had a formative influence on its hadith tradition. First, the failure of the early Muslims to acknowledge collectively that ‘Ali and his descendants should have been the rightful political and religious rulers in Islam made the idealistic Sunni vision of the early Muslim community untenable. Unlike the categorical trust that Sunnis placed in the reliability of the Companions as hadith transmitters, Shiites believed that even this founding generation had failed. Any Companion who did not support ‘Ali’s claim to succeed the Prophet was at best complicit with injustice, at worst an active denier of the truth.

Second, for the Imami Shiites, like other Shiite groups who identified religious leadership with the Prophet’s descendants, this reliance on the family of the Prophet resulted in a crisis when the line of imams seemed to come to an end. In 260/874, Hasan al-‘Askari, the eleventh imam, died in captivity in the Abbasid court. A young man, he had no heir that the public knew of. The Shiite imams had served as the authoritative interpreters of the Quran, the Prophet’s legacy, and Islam in general for their followers. Who now would meet this need? Some members of the Shiite community claimed that the eleventh imam had indeed had a son, who had been hidden away by the community from the Abbasid caliph. Tired of the unjust and iniquitous world, the infant boy had vanished in an underground cave in Samarra, to return in the future as the rightly guided Messiah (Mahdi) and ‘fill the world with justice as it had been filled with injustice.’ In the coming decades, certain members of the community claimed to be in contact with the ‘Hidden Imam,’ even delivering questions posed by members of the community to him. Eventually the prominent Shiite noble Ibn Rawh al-Nawbakhti formalized this function, announcing that he and two predecessors were ‘ambassadors (safir)’ of the Hidden Imam.4

In 329/941 the third formative event occurred: the last of the ‘ambassadors’ died. This controversial office, claimed disputably by many, proved too problematic to both the Hidden Imam and his community, and all contact between the two would be cut off until the Imam’s return. The last ‘ambassador’ informed his followers soon before his death that the Hidden Imam had instructed him that anyone from that point on who claimed contact with the Imam was a fraud.5 The Shiite community, who had held that God would not leave His community without an authoritative interpreter of His religion, found itself completely alone. This duty would now fall upon the shoulders of the scholars. Although not in contact with him, they would act as the Hidden Imam’s regents until his return.

It is in this period of crisis, beginning with the initial disappearance of the twelfth imam and reaching a crescendo with his ultimate occultation (passing into a state of supernatural seclusion), that we find the earliest development of Imami Shiite doctrine and hadith. First, the Imami community, with its centers at Qumm and Rayy in Iran, would have to distinguish itself from other Shiite groups who believed that it was in fact earlier imams who had represented the end of the earthly Alid line and would return as the awaited Mahdi. Hasan b. Musa al-Nawbakhti’s (d. between 300–310/912–922) and Sa‘d b. Abdallah al-Qummi’s (writing 292/905) ninth-century books on various sects of the Shiites are the first surviving articulations of Imami doctrine. These books seek to carve out a doctrinal identity for the Imami Shiites that distinguishes them from both the earlier Shiite extremist groups, such as those that believed that ‘Ali was divine, as well as the groups such as the Ismailis (many of whom awaited the return of the imam Isma‘il, the brother of the seventh imam Musa al-Kazim, whom they claimed was in occultation) and the Waqfiyya sect, who believed that it was Musa al-Kazim who had gone into occultation.

Furthermore, who was this twelfth ‘Hidden’ imam, unknown to all but a few prominent Shiites, and what was the nature of his occultation? Even many of the Shiite families who had believed in the imamate of the Hidden Imam’s father al-Hasan al-‘Askari did not know the answer to these questions. The scion of a great Shiite family of Qumm, Ibn Babawayh (d. 381/991), attempted to clarify these points to his community in his Epistle on Beliefs, which comprehensively formulated the doctrine of Imamis.6

What heritage did Imami Shiite scholars like Ibn Babawayh have to draw on in their efforts to define Imami law and doctrine? Like many pious Muslims in the first three generations of Islam, those individuals who believed that the family of the Prophet enjoyed a special status or religious authority collected the sayings and rulings of the imams in order to preserve their legacy. In particular, the students who flocked around the sixth imam, Ja‘far al-Sadiq (The Truthful), in Medina collected their notes of his teachings. The legacy of his son, the seventh imam, Musa al-Kazim, was also collected in numerous small books by his students. Even until the time of the eleventh imam, devotees of the family of the Prophet labored to record their teachings, rulings, and interpretations of the Quran.7

A notebook of sayings of imams like Ja‘far al-Sadiq was called an asl (‘source,’ pl. usul). Hundreds (Imami Shiites have traditionally talked of the ‘four hundred usul,’ but other numbers have been mentioned as well) of these usul were compiled, sometimes by a student of the imam recording his teachings directly and sometimes through an isnad from the imam to a slightly later collector. The usul contained the material essential for formulating a religious and communal vision: elaborations of doctrine, answers to legal queries and polemics against those who opposed the rightful station of the ahl al-bayt (The Family of the Prophet).

In addition, early Shiite compilers collected books on the virtues (fada’il, khasa’is) of ‘Ali and his progeny as well as the history of their careers. Zayd b. Wahb (d. 96/714–15), a Kufan devotee of the family of the Prophet, compiled a book of the sermons of ‘Ali (Kitab khutab amir al-mu’minin).8

Like the Sunni hadith tradition, some of these early books may really have been written after the deaths of their supposed authors by some later figure. Even some Shiite scholars, for example, doubt the authenticity of a book of hadiths attributed to the Successor Sulaym b. Qays al-‘Amiri called Kitab al-saqifa.9 Some of the usul drew on these dubious early books, like the ‘Book of the Sunna, Rulings and Judicial Cases’ (Kitab al-sunan wa al-ahkam wa al-qadaya) of the Companion Ibrahim Abu Rafi‘ and al-Sahifa al-sajjadiyya attributed to the fourth imam, ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin.10 These early books may have really existed, or they may have been conjured up by later Shiites eager to show that ‘Ali and his descendants truly had some special knowledge, in book form, that no other Companions possessed.

For the Imami community, eager to elaborate a clear doctrine, ritual, and law in the absence of its imam, however, these usul were not very useful. They needed to be reorganized according to topic. Starting in the early eighth century, Shiite scholars began making selections of hadiths and organizing them into ‘compendia’ (jami‘, pl. jawami‘) and ‘topical books’ (mubawwab). These books could either address one issue or, like the musannaf and sunan books of the Sunnis, a whole range of subjects. For example, Ja‘far al-Sadiq’s student Ghiyath b. Ibrahim had compiled a book of the imam’s teachings organized along the lines of what was permitted or forbidden for various legal topics.11 Ibn al-Qaddah (d. c. 180/796–7) collected a book of hadiths specifically on the nature of heaven and hell.12

These early topical collections by students of the imams provided a foundation for the Imami Shiite community to draw from and build on. Muhammad b. al-Hasan al-Saffar al-Qummi (d. 290/903) wrote the famous Basa’ir al-darajat, which specifically dealt with the virtues and prerogatives of imams.13 Ibn Babawayh’s Kitab al-jami‘ liziyarat al-Rida provided reports on the virtues of the eighth imam and the importance of visiting his grave, while the Kitab al-jami‘ al-kabir fi al-fiqh by Ibrahim b. Muhammad al-Thaqafi (d. 283/896) more closely resembled a comprehensive sunan book.14 A tafsir replete with reports about why verses of the Quran were revealed was attributed to the eleventh imam al-Hasan al-‘Askari (although Shiite scholars debate whether or not the imam actually wrote it).

Even as the usul and early books were broken up to create these topical works, some Shiite scholars like Ahmad Ibn ‘Uqda (d. 332/944), who were deeply committed to hadith transmission, continued to transmit the usul in their original form – approximately thirteen survive today.15 It is interesting that, as Ron Buckley has noted, Shiites started compiling topical collections of hadiths as part of developing their law at approximately the same time that great Sunni scholars such as Malik b. Anas and al-Bukhari were doing the same.16

These topical works of law, ritual, and doctrine formed the basis for what became the four books of the Shiite hadith canon: the Kafi fi ‘ilm al-din of Muhammad b. Ya‘qub al-Kulayni (d. 329/939), the Man la yahduruhu al-faqih of Ibn Babawayh (d. 381/991) and the two collections of Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. al-Hasan al-Tusi (d. 460/1067), the Tahdhib al-ahkam and the Istibsar fima ukhtulifa fihi al-akhbar. While the Sunni hadith canon is made of books very similar to one another in structure and purpose (they are all from the sunan genre), the components of the Shiite canon represent varying tools for different visions of the role of hadith in religious rulemaking.17

Al-Kulayni offered his massive al-Kafi fi ‘ilm al-din (The Sufficient Book in the Knowledge of Religion) as a source for Shiites who could not find scholars possessing true knowledge of Islam or sort out the tangled web of reports narrated from the Prophet and the imams. Al-Kulayni says that this dearth of knowledge was due to the unwillingness of scholars to resort only to ‘the Quran and the Prophet’s sunna with true knowledge and understanding.’ Instead, they have turned to blind imitation (taqlid), what they saw as their own best judgment (istihsan) and baseless interpretation (ta’wil). The Kafi, al-Kulayni says, is the answer. It will suffice for ‘those who want knowledge of the religion and to act on it according to authentic reports from the Truthful Ones [i.e., the imams] and the established Sunna that is the basis for right legal action.’18 The Kafi covers the whole range of legal topics applicable in Muslim life as well as the issues of the origins and nature of the imamate. Like al-Bukhari’s Sahih, the very structure of the books explains the lessons the reader should derive from it; the titles of each subchapter instruct the reader how to understand the hadiths it includes. The author trusts the book to be its own explanation.

A generation later, the great Ibn Babawayh compiled another comprehensive topical hadith collection designed to assist Imami Shiites who had no other source for understanding Islam properly. His Man la yahduruhu al-faqih (He Who Has No Legal Scholar at Hand) is even more consciously a reference work than the Kafi. Unlike al-Kulayni, Ibn Babawayh does not provide full isnads for each hadith. He does not want the reader to concern himself with such specialized details, but rather assures his audience that he has only included reports that are authentic.19

Ibn Babawayh and early Imami scholars sought to meet the immediate challenges facing the community with reports from the Prophet and imams alone as evidence. Ibn Babawayh’s most famous student, Muhammad b. al-Nu‘man al-Harithi (d. 413/1022), called al-Shaykh al-Mufid, however, was a Mu‘tazilite rationalist who saw hadiths as only a limited component of elaborating law and doctrine for the Imami community. Hadiths should be part of a larger framework for understanding Islam, used properly and supervised by a more authoritative master: reason. As a follower of the Mu‘tazilite school in Baghdad, al-Shaykh al-Mufid believed that rational investigation was an essential tool for determining correct belief, and he abandoned his teacher Ibn Babawayh’s reliance on using ahad reports from the imams as evidence in many issues.20

It was one of al-Shaykh al-Mufid’s students in Baghdad who would be responsible for half of the Shiite hadith canon and become one of the most influential scholars in Shiism: Muhammad b. al-Hasan al-Tusi (d. 460/1067). While al-Kulayni and Ibn Babawayh had assured their readers that their books consisted of only authentic hadiths, al-Tusi’s two hadith works made this authentication process more transparent. Furthermore, for him hadiths were clearly just one part in a larger process of deriving law. Al-Tusi’s first book, the Tahdhib al-ahkam, is in fact not a true hadith collection at all. It is a commentary on a legal work by al-Shaykh al-Mufid (called al-Muqni’), structured along its lines but focusing on its hadiths. Al-Tusi’s al-Istibsar fima ukhtulifa fihi al-akhbar (Seeking Clarity on that which Reports Differ) resembles much more closely the books that Sunni scholars like al-Shafi‘i devoted to sorting out and reconciling hadiths that seemed to contradict one another: books of ikhtilaf al-hadith (see Chapter 5).

Western scholars refer to these four collections as the Shiite hadith ‘canon’ because Shiites consider them the most authoritative sources for hadiths.21 In effect, with the compilation of these four works, the earlier usul and topical hadith collections became practically obsolete.22 The authority of the canonical collections does not, however, entail that criticizing the authenticity of hadiths in them is unseemly or impermissible. Their canonicity derives from their widespread acceptance and use, not their infallibility.

Of course, the formation of the Shiite hadith canon did not mean an end to Shiite hadith literature. Ibn Babawayh devoted several books to explaining the legal reasoning behind a selection of hadiths as well as explaining the meanings of controversial or confusing hadiths (his ‘Ilal al-shara’i‘ and Ma‘ani al-akhbar). We also have the surviving records of great Shiite scholars like Ibn Babawayh giving dictation sessions (amali) to students in which they would narrate a selection of hadiths from the Prophet, the imams, and even Sunni hadith transmitters for teaching purposes. Of course, Shiite scholars continued to write about the virtues of the imams in books like Khasa’is? amir al-mu’minin by al-Sharif al-Radi (d. 406/1015) and the Kitab alirshad fi ma‘rifat hujaj Allah ‘ala al-‘ibad by al-Shaykh al-Mufid. Although not strictly a hadith collection, al-Sharif al-Radi’s Nahj albalagha (The Path of Eloquence), a collection of what are said to be the speeches of ‘Ali b. Abi Talib (of which some are clearly among the oldest surviving pieces of Arabic writing), is seen as a literary masterpiece by Shiites and Sunnis alike (although Sunnis consider much of the book to be forged).23 Also frequently cited is Ibn Shahrashub’s (d. 588/1192) collection of all the literature on the lives, virtues and feats of the imams: the massive Manaqib Al b. Abi Talib.

The greatest transformative step that the Shiite hadith tradition took after its canon had formed, however, occurred much later. In the early seventeenth century, a movement arose among Shiite scholars in the Hijaz, Iraq, and Iran that opposed what it viewed as the overly rationalist character of Imami Shiite thought as well as the overly hierarchical structure of the Shiite clergy. Followers of this trend believed that Imami Shiites should reaffirm their reliance on the hadiths of the Imams as the only true way to understand law and dogma properly, and they were thus known as the Akhbari school (because of its reliance on akhbar, reports). This led to a renewed interest in collecting and commenting on Shiite hadiths in the seventeenth century.24

Although Shiites did not develop as extensive a tradition of penning massive commentaries on their hadith collections as did Sunnis, in this period they did amass several mega-collections that combined and commented on existing hadith works, and some of which are more gigantic than even the largest Sunni commentary.25 Three of these mega-collections are extremely well known. The first is the Wasa’il al-shi‘a ila ahadith al-shari‘a (The Paths of the Shiites to the Hadiths of the Holy Law) by Muhammad b. al-Hasan al-‘Amili (d. 1104/1693). Second, Mulla Muhsin Fayd al-Kashani (d. 1091/1680) wrote a massive digest and commentary on the four canonical hadith collections, entitled al-Wafi. The last is a work astounding not only in its vast size, but also in the great accuracy with which its author drew on and cited earlier books. The mammoth Bihar al-anwar (Oceans of Light) by Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi (d. 1110/1700), one hundred and ten printed volumes, is so enormous that one needs a guidebook, the Safinat al-bihar (The Ship of the Seas) by ‘Abbas al-Qummi (d. 1936) to navigate it effectively. The Bihar covers almost all the topics pertinent to Shiite history, belief, and law. Not only does Majlisi’s huge collection include the material found in earlier hadith books, the author also unearthed old manuscripts of usul that survive only in his book.26 Majlisi’s work is encyclopedic, not critical, and he left his readers to decide what material is authentic or not.

Shiite hadith criticism began much later than its Sunni counterpart, appearing in full force only in the early eleventh century. While the imams were alive, there was no need to worry about forged hadiths – any reports attributed to an earlier imam would be checked by his descendants.27 In the immediate wake of the twelfth imam’s disappearance, however, Shiites like al-Kulayni, and later Ibn Babawayh, understood that it was now the responsibility of scholars to assure that the Shiite community only acted on reports authentically traced to the imams. The failure of scholars to distinguish between reliable and unreliable hadiths had been a leading motivation for the writing of al-Kulayni’s and Ibn Babawayh’s collections. Writing in the decades after the final occultation of the twelfth imam, Ibn Babawayh already acknowledged that the two usul books of Zayd al-Zarrad and Zayd al-Narsi were forged.28

Early Shiite hadith scholars like al-Kulayni and Ibn Babawayh had believed that the usul of the imams contained all the knowledge necessary for the Shiite community to survive during the Hidden Imam’s absence. This school of thought, later known as the akhbari school, considered the four canonical collections to be totally reliable records of the earlier usul books. With the rise of the Shiite Mu‘tazilite school of al-Shaykh al-Mufid in Baghdad (later the origin of the Usuli school, which advocated the use of independent legal reasoning and a more critical use of hadiths), Shiite scholars began to look more skeptically at the contents and use of these collections. They acknowledged that some reports in these books could have been inserted by Shiites with deviant beliefs. Moreover, even a pious and well-intentioned usul compiler could have made an error in including one report instead of another. Like the Sunnis, some Imami Shiites forged hadiths to help reinforce communal identity. One forged hadith, for example, said that visiting the grave of the eighth imam, ‘Ali al-Rida, in Mashhad was worth seventy pilgrimages to Mecca.29

Like the Sunni tradition, Shiite hadith criticism centered on evaluating transmitters and then using this information to help decide the reliability of isnads. Proper belief was the centerpiece of Shiite transmitter criticism. Before the occultation of the twelfth imam and the formation of a distinct Imami Shiite community, there was a sense that a Muslim’s realization that the family of the Prophet was the sole religious authority was testament enough to his reliability. It was thus reported that Ja‘far al-Sadiq had said, ‘Know the status of people by the extent to which they narrate from us (i‘rifu manazil al-nas ‘ala qadr riwayatihim ‘anna).’30

As the Shiite scholarly tradition grew more elaborate, however, this would not suffice. Al-Shaykh al-Mufid’s student, the famous al-Tusi (d. 460/1067), began developing a system of transmitter criticism to weed out reports from unreliable people and ensure that Shiites were only taking hadiths from ‘the party of truth.’31 Although al-Tusi seems to have been the first Shiite to employ a system of rating the reliability of transmitters, like the Sunnis, Shiite hadith scholars had long been keeping records in order to identify the myriad of people who made up their isnads to the imams. Ahmad Ibn ‘Uqda (d. 332/944) devoted a large book to identifying all the people who studied with and transmitted the teachings of Ja‘far al-Sadiq, Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Hamdani (d. 333/944–5) wrote a book entitled ‘The Book of Dates and Those Who Narrated Hadiths (Kitab al-tarikh wa dhikr man rawa al-hadith),’ and later Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Jawhari (d. 401/1010–11) compiled a work called ‘The Comprehensive Book on Identifying Hadith Transmitters (Kitab al-ishtimal ‘ala ma‘rifat al-rijal).’32 Although these books have been lost, the earliest surviving book on Shiite transmitters, that of Muhammad b. ‘Umar al-Kashshi (d. c. 340/951), focuses on laying out the full names of transmitters, their relationships to other transmitters and, if possible, when they lived. Like many early Sunni books of hadith transmitters, these books were concerned more with identifying transmitters than criticizing them.

When he began his efforts to make sure no fraudulent material had crept into the usul since the disappearance of the twelfth imam, al-Tusi had to ensure that Shiites had received material from Muslims with the proper beliefs. Certainly, Imami Shiites needed to be on guard against hadiths forged or propagated by anti-Shiite Sunnis. But the more immediate danger was sifting out reports from Shiites who had extremist beliefs like the deification of ‘Ali and those who believed that the line of the Prophet had ended with an earlier imam going into occultation. Before worrying about Sunni opponents, the Imami community had to demonstrate that it was not extremist and to distinguish itself from other Shiites.

Al-Tusi’s book of transmitter criticism (Rijal al-Tusi) is thus more concerned with identifying Shiite transmitters who believed that it was actually an earlier imam, like Musa al-Kazim, who had disappeared and ended the imamate than with criticizing anti-Shiite Sunnis. Ibn Hanbal, a fierce critic of Shiism, is mentioned in the books with no disapproving comment, while many Shiites are dismissed for their belief in the occultation of an earlier imam or their extremist Shiite beliefs. Al-Tusi tries to list those transmitters who collected usul from the imams, determining whether they are ‘trustworthy (thiqa)’ or not.

Abu al-‘Abbas al-Najashi (d. 450/1058) followed al-Tusi in compiling an influential book of Shiite transmitter criticism, the Rijal al-Najashi. Unlike, al-Tusi, however, he aimed his book at a Sunni audience. Tired of his opponents accusing Shiites of having no tradition of hadith transmission and hadith books, he offers example after example of accomplished Shiite hadith authors and the isnads in which he found them. He even uses books of Sunni transmitters to help in his evaluation. It appears, in fact, that al-Najashi was consciously imitating the methods and language of Sunni transmitter criticism; he frequently called narrators ‘weak (da‘if),’ or ‘having accurate transmissions (sahih al-sama‘),’ just like his Sunni contemporaries.

Al-Tusi not only seems to have been the first Imami scholar consistently to evaluate hadith transmitters, he was also the first to apply these criticisms to authenticate or dismiss hadiths. In the Istibsar he uses isnad criticisms to show how what seems to be two contradictory hadiths is really just an unreliable hadith clashing with a reliable one.33 The Shiite science of isnad criticism was further developed by Jamal al-Din b. Tawus (d. 673/1274) of Baghdad and the great founder of the Hilla school in Iraq, ‘Allama Muhammad b. Idris al-Hilli (d. 726/1325).

Shiite hadith criticism continued to draw on and in effect mirror Sunni hadith criticism. The first major book defining the technical terms and methods of Shiite hadith criticism, written by al-Shahid al-Thani (d. 965/1558) (entitled ‘Knowledge of Hadith, Dirayat al-hadith’), is basically a digest of the Sunni Ibn al-Salah’s famous Muqaddima. Only on a few important issues does the Shiite method diverge from its Sunni counterpart. For example, a hadith is defined as the report transmitted from any ‘infallible (ma‘sum)’ individual, not just the Prophet. This allows for the Shiite reliance on the hadiths of the imams.34 The concern for avoiding extremist Shiites or believers in earlier vanished imams appears clearly in the labels that Shiites use to indicate unreliable narrators: ‘extremist (ghal)’ and ‘believing in the occultation of an earlier imam (Waqifi),’ from whom one can accept hadiths only before he adopted deviant beliefs.35

Allowance is made for occasionally narrating from Sunnis: one of the sub-grades of hasan hadiths, ‘trustable (muwaththaq),’ is defined as a hadith that is reliable even though a Sunni is in the isnad.36

Al-Shahid al-Thani sharply critiques his Sunni brethren by noting how they concerned themselves only with the outward signs of a transmitter’s upright character (‘adala), ignoring the need for an appropriate belief in the family of the Prophet. Hence, he says with an air of tragedy, there is such a plethora of supposedly ‘authentic’ hadiths in Sunni eyes.37 As the Sunnis knew well, Mu‘tazilism had always held an examination of the contents of a hadith to be the final arbiter in determining its authenticity. The Shiite adoption of the Mu‘tazilite framework in the eleventh century thus meant that content criticism would enjoy a more prominent role in Shiite hadith criticism than it did among Sunnis. Just because the isnad was reliable did not mean the report was authentic or legally compelling.38 Al-Sharif al-Murtada (d. 436/1044) maintained that every report attributed to the Prophet or imams had to be authenticated by reason.39 Influential scholars like ‘Allama al-Hilli would not even accept the medium grade of reports, hasan, because they were too unreliable.40

Interestingly, even the earlier akhbari scholars like al-Kulayni had reserved an important role for content criticism. The Kafi cites a number of hadiths from the Prophet and Ja‘far al-Sadiq with statements like ‘Everything is compared to the Book of God and the Sunna, and any hadith that does not agree with the Book of God is but varnished falsehood.’41 While Sunni scholars had uniformly rejected statements such as Ja‘far’s because they contradicted the important role of hadiths in explaining and modifying the Quran (see Chapter 5), Shiites embraced them as an indication of the importance of content criticism.

Although we have seen some of the important differences between the Sunni and Shiite traditions of hadith study, they have never been totally separate. They share common origins, overlap, and have interacted with one another over the course of Islamic history. The chief factors for the commonalities or interactions between the two have been the decidedly non-sectarian beliefs of many early Shiites, the lingering (and sometimes burgeoning) devotion to the family of the Prophet among Sunnis, and the Shiite need to draw on Sunni hadiths in their defense of Shiite doctrine.

To what extent can we talk about separate bodies of Sunni and Shiite hadiths? In the first two hundred years after the death of the Prophet, the majority of early Shiites did not espouse a doctrine that differed dramatically from the majority of Muslims. Of course, there were those supporters of ‘Ali and his family who despised or totally rejected the legitimacy of the first two rulers after the Prophet – Abu Bakr and ‘Umar – who were lionized by mainstream Sunni Islam. Sunnis could generally not accept such Shiites as Muslims in good standing. Other early Shiite extremists believed that ‘Ali was God incarnate and were thus ostracized uniformly by other Muslims, Sunnis and Shiites alike. There was also a germinating Imami community who looked to the Shiite imams for sole religious guidance. Most early Shiites, however, were merely characterized by ‘an enhanced reverence’ for the descendants of the Prophet, an attraction to their charisma and support for their general disapproval for the less-than-ideal regimes of the Umayyads and early Abbasids.42 Love for the family of the Prophet was particularly intense in Kufa, ‘Ali’s adopted capital and the setting for many ‘Alid revolts against the Umayyads. In fact, Sunni hadith critics accepted that, in the case of a Kufan transmitter, such loyalties did not mean the transmitter was necessarily Shiite. It was just part and parcel of being Kufan.

Although never considered infallible religious authorities or the perennial rightful rulers of Islam, the family of the Prophet has always been venerated in Sunni Islam. Certainly, in times of intense Sunni/Shiite conflict or in the writings of diehard Sunnis like Ibn Taymiyya (d. 728/1328), Sunnis have deemphasized this. Even the notoriously anti-Shiite Shams al-Din al-Dhahabi (d. 748/1348), however, warned ‘May God curse those who do not love ‘Ali.’43

Especially in the first two centuries of Islam, many scholars later glorified by Sunni Muslims, such as Abu Hanifa and al-Shafi‘i, displayed pronounced affection for the family of the Prophet. Brought before the Abbasid caliph on charges of being an extreme Shiite, al-Shafi‘i composed a verse of poetry proclaiming that, if loving the family of the Prophet was being a heretic, then he would proudly admit to that charge. Even the most trusted Sunni hadith collections contain hadiths urging Muslims to love and honor the Prophet’s family and descendants. Al-Bukhari included in his famous Sahih the report in which the Prophet said, ‘Fatima is part of me, so whoever has angered her has angered me (Fatima bid‘a minni fa-man aghdabaha aghdabani).’44

In the seventh and eighth centuries, much of what would make up the Shiite hadith corpus was just hadiths expounding the virtues of ‘Ali.45 Sunni hadith critics embraced much of this material. Ibn Hanbal himself commented that ‘there has not appeared via authentic isnads, hadiths testifying to the virtues of any Companion like what has appeared testifying to the virtues of ‘Ali b. Abi Talib.’46

In the eighth century, however, as the sayings of imams like Ja‘far al-Sadiq were compiled, we see the emergence of an independent body of specifically Shiite hadiths.47 By the time of the twelfth imam’s final disappearance in 941 CE, the body of material that made up the Shiite hadith corpus was effectively complete.48 What sorts of hadiths did this corpus consist of?

First, we find hadiths that are simply not found among Sunnis, such as hadiths in which the Prophet is quoted as explicitly foretelling the coming of the twelve imams and ordering Muslims to follow them, or the hadiths of the imams themselves. Sunnis would never accept hadiths requiring them to believe in the Twelver imamate, nor would they even consider the reports of the imams as counting as ‘hadiths.’ With their collection of the hadiths of the imams, the Shiites thus built up a body of material totally absent in Sunni hadith collections even though they might dovetail perfectly with Sunni themes. Reports in the Kafi in which Musa al-Kazim curses those who use analogical reasoning to derive Islamic law would fit seamlessly into the writings of Ibn Hanbal or al-Bukhari, but the fact that they were the hadiths of an imam put them outside the pale of Sunni Prophetic hadiths.49

Second, we find pro-Shiite hadiths that appear in Sunni books but without the sectarian element. In the collection of Ibn Babawayh’s dictation sessions (Amali), he narrates a hadith that the pro-‘Alid Companion Jabir b. ‘Abdallah narrated from the Prophet: ‘ ‘Ali b. Abi Talib is the earliest to embrace Islam in my community, the most knowledgeable of them, the most correct in his religion, the most virtuous in his certainty, the most prudent, generous and brave of heart, and he is the imam and caliph after me.’50We find that many Sunni hadith collections, even early ones such as the Musannaf of ‘Abd al-Razzaq al-San‘ani (d. 211/826) and the Musnad of Ibn Hanbal, include the section of this hadith that says that ‘Ali is ‘the earliest to embrace Islam in my community, the most knowledgeable of them.’ The sections ordaining him as caliph and imam, however, are absent.

Third, we find hadiths with a distinct pro-‘Alid content that both Sunnis and Shiites accept equally. For example, the famous hadith of Ghadir Khumm, in which the aging Prophet stops his followers by the pool of Ghadir Khumm and tells them ‘Whoever’s master I am, ‘Ali is his master.’ The vaunted Sunni hadith critics al-Tirmidhi and al-Hakim al-Naysaburi both considered this report to be authentic. In another hadith that al-Hakim, Ibn Khuzayma, and even the great Muslim b. al-Hajjaj include in their Sahih collections, the Prophet tells his followers, ‘Indeed I am leaving you with two things of great import (thaqalayn) ... you will not go astray as long as you hold fast to them: the Book of God and my family.’

Of course, Sunnis and Shiites have upheld two very different interpretations of these hadiths. Shiites view them as clear evidence that Muhammad wished ‘Ali and his descendants through Fatima to succeed him both in temporal and religious leadership of the Muslim community. Sunnis view them as two exhortations to honor ‘Ali and the Prophet’s family, but contextualize such hadiths with the plentiful pool of reports in which the Prophet praises his leading Companions like Abu Bakr and ‘Umar using the same language and appears to reserve places of leadership for them.

Some Sunnis were less patient with such pro-‘Alid hadiths than others. Al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, who was so accepting of pro-‘Alid reports that he was accused of Shiism, declared authentic the hadith in which the Prophet supposedly said, ‘O Fatima, God is angered when you are angered, God is pleased when you are pleased.’ Al-Hakim’s teacher, al-Daraqutni (d. 385/995), however, was not so generous. He exposed it as a hadith that the fifth imam Muhammad al-Baqir attributed directly to the Prophet – a typical and laudable Shiite isnad, but a case of broken transmission (mursal) according to Sunnis.51

Finally, many Shiite hadiths appear in the Sunni collections that aimed merely at collecting as many hadiths as possible and made no pretension at any critical stringency. Many of these collections, such as the Hilyat al-awliya’ (The Adornment of the Saints) of Abu Nu‘aym al-Isbahani (d. 430/1038), were works devoted to documenting the rich heritage of Sufism and therefore included a great deal of pro-‘Alid material. ‘Ali was, after all, seen as the progenitor of the Sufi tradition and the beginning of most of the isnads though which the Sunni Sufi orders traced their teachings to the Prophet (see Chapter 7). These reports were generally innocuous, with no sectarian edge, and urged goodly and pious behavior. While Ibn Babawayh quoted the fifth imam Muhammad al-Baqir that the Prophet had said that the best of God’s slaves are those ‘Who, when they seek perfection in their acts, hope for good tidings, seek forgiveness when they do wrong, are thankful to God when they give, persevere when they are tried, and forgive when they are angered,’ Abu Nu‘aym cites it through a very Sunni isnad in his Hilyat al-awliya’.52

The biggest factor in the Sunni embrace of many Shiite hadiths was the veneration for the family of the Prophet that gained great currency among the Sunni Muslim majority of Egypt, Iraq, Iran, and Central Asia beginning in the eleventh century. In that time, almost every village and town ‘discovered’ its own imamzade, or the tomb of a pious descendant of the Prophet, to serve as a local pilgrimage and miracle center.53 The Sunni fascination with the family of the Prophet as a medium for baraka (blessing) led to a widespread study and transmission of hadiths narrated through the Shiite imams, even if professional hadith scholars like al-Dhahabi and Mulla ‘Ali Qari (d. 1014/1606) decried such books as forgeries. In the Iranian city of Qazvin in particular, the Sahifa of the eighth imam ‘Ali Rida (d. 203/818), who traced his isnads back through the imams to the Prophet, became widely transmitted for pietistic purposes. Most of its contents were harmless pieces of advice, such as ‘Knowledge is a treasure, and questions are its key.’54

The religious power of an isnad through the imams sometimes manifested itself in bizarre and miraculous reports. The great Sunni hadith critic Ibn Abi Hatim al-Razi (d. 327/938) is reported (falsely, in my opinion) to have said that once, when he was in Syria, he saw a man unconscious in the road. He remembered that one of his teachers had once told him, ‘the isnad of ‘Ali Rida, if it is read over a senseless person, he’ll recover.’ Ibn Abi Hatim tried out this cure, and the man returned immediately to health.55

As we found in our discussion of Sunni hadiths, for Sunni critics a hadith transmitter’s sectarian affiliation ultimately took the back seat to his or her reliability in transmission. If you consistently transmitted hadiths that were corroborated by other experts, even deviant beliefs would not disqualify you from participating in the Sunni hadith tradition. Individuals with pronounced Shiite leanings, such as ‘Abd al-Rahman b. Salih (d. 235/849–50) and Sa‘id b. Khuthaym (d. 180/796–97), thus served as respected and valued transmitters in mainstay Sunni hadith books such as the Sunans of al-Nasa’i and al-Tirmidhi. In theory, Sunni hadith critics restricted themselves from accepting the transmissions of Shiite narrators who tried to convert others to their cause (since this might provoke them to forge pro-Shiite hadiths) or, at the very least, not accepting those hadiths with a pro-‘Alid message from such Shiite transmitters. In reality, however, even the great Muslim b. al-Hajjaj included in his Sahih a report from a known Shiite, ‘Adi b. Thabit (d. 116/734), in which the Prophet announced that only a believer could love ‘Ali and only a hypocrite could hate him.

As such, we find a marked overlap of transmitters between the Sunni and Shiite hadith traditions. Aban b. Taghlib (d. 140/757) was a well-known and devoted Kufan Shiite who appears as a narrator from the imams in al-Kulayni’s Kafi, but all the Sunni Six Books except Sahih al-Bukhari included his hadiths as well. ‘Abdallah b. Shubruma was a major Shiite jurist in Kufa and a hadith transmitter used in the Shiite hadith canon. He also carried weight among Sunni jurists, and Muslim and al-Nasa’i used him as a transmitter in their hadith collections.

On rare occasions, there was also overlap between Sunnis and Shiites on influential hadith critics. Ibn ‘Uqda (d. 332/944) was the most important collector of the Shiite usul and a pioneer in compiling the names of Shiite transmitters.56 Yet he was praised by the most prominent Sunni critics of his day, like al-Daraqutni and Ibn ‘Adi, and later the scholar al-Subki (d. 771/1370) called him ‘one of the hadith masters of the Shariah;’57 this, even though he was such a staunch Shiite that he occasionally disparaged Abu Bakr and ‘Umar. He commanded one the most impressive memories of his day, either having memorized or being current with 850,000 hadiths, 3,000 from the family of the Prophet alone. When he wanted to move from his native Kufa, he found that his personal library of six hundred camel-loads of books prevented him.58 Not only did Sunnis appreciate Ibn ‘Uqda’s command of hadith transmissions, they also valued his opinions on evaluating transmitter criticism. In fact, the earliest evaluation of al-Bukhari’s and Muslim’s famous Sahihayn comes from Ibn ‘Uqda.

Imami Shiism matured under the looming shadow of the Sunni Abbasid caliphate and had to survive under Sunni states such as the Seljuq Turks, the Ilkhanid Mongols, and the Ottoman Empire. Even during periods in which Shiites achieved political ascendancy, such as the tenth century (called the ‘Shiite Century’ because the Shiite Buyids ruled Iraq and Iran, with the Shiite Fatimids in Egypt and Syria), Shiites still lived as a minority among the Sunni masses. Shiite scholars very much appreciated the use of Sunni hadiths, especially reports with a pro-‘Alid bent, as tools for either debating their Sunni opponents or convincing them that Imami Shiism presented no threat to Sunni Islam. The Shiite scholar Radi al-Din Ibn Tawus (d. 664/1266) kept a digest of the Sahihayn in his library for such uses.59 In such cases, Shiites would abandon their own method of hadith criticism and play by Sunni rules in the hopes of convincing Sunnis on their own terms.

Ibn Babawayh, for example, began one of his dictation sessions in the mosque with a hadith narrated from the Prophet by Abu Hurayra, whom Shiites considered an arch-liar who had covered up ‘Ali’s right to the caliphate by forging hadiths to the contrary. In this hadith, however, Abu Hurayra is quoted telling the Muslims to fast on the eighteenth of the month Dhu al-Hijja because that was the day of Ghadir Khumm – the day when the Prophet had announced to his followers that ‘Ali was to be their master after him.60 In his efforts to prove that no one in history had ever been named ‘Ali before ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, the Shiite scholar of Qazvin, Abu al-Husayn Qazvini (d. c. 560/1165), invoked as evidence the Sahihayn and other Sunni hadith books that ‘are relied upon.’ Qazvini tells his opponents to ‘take up the Sahihayn’ and find the hadith that says that ‘Ali’s name is written on the leg of God’s throne and on the doorway to Paradise as the brother of Muhammad. Since both these structures existed before the creation of the world, ‘Ali is doubtless the first person to have been so named.61 Qazvini’s attempt was admirable, but it did not convince his opponents; the hadiths he cited were nowhere to be found in the Sahihayn or any reputable Sunni collection.62

Zaydism is a branch of Shiism associated with Zayd b. ‘Ali (d. 122/740), son of the fourth imam ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin, who rebelled unsuccessfully against the Umayyads in the twilight days of their rule. Although Zaydi Islam is a relatively small sect, flourishing in classical times in Kufa and northern Iran but now limited to northern Yemen, its hadith tradition deserves attention due to both its originality and influence.

Zaydis believe that the true teachings of Islam, as a religious system and a message of political justice, have been preserved by members of the family of the Prophet who rose up against the tyrannical and impious rule of the Umayyads, Abbasids, and later dynasties. Unlike Sunnis, Zaydis do not see early Islamic history as an idealized expansion of the pure faith under ultimately legitimate Muslim rulers. Zaydis believe that ‘Ali should have been the first caliph, but, unlike Imami Shiites, they believe that the Prophet’s instruction on this matter was ambiguous.63 Zaydis also break with Imami Shiism by not attributing a specific line of infallible, divinely specified imams with any special access to the esoteric truths of Islam and the Quran. Nor do they pay any special attention to the awaited Hidden Imam. Instead, Zaydis believe that the family of the Prophet is the historical protector and preserver of the true teachings of Islam and that it is their duty to stand up for justice in the face of oppressive rulers. Any member of the family of the Prophet who combines a mastery of Islamic scholarship with an ability to stand up against injustice has the right to call himself the imam. In many ways, Zaydism is a middle ground between Sunni and Imami Shiite Islam.

In their outlook on hadiths, Zaydis can be distinguished from Sunnis by four features: 1) an enhanced reverence for the family of the Prophet, 2) a case-by-case evaluation of the Companions, 3) a more cynical view of early Islamic history, and 4) their Mu‘tazilite thought. Zaydis summarize this with a quote from their Imam al-Hasan b. Yahya b. al-Husayn b. Zayd b. ‘Ali:

The solution to disagreements over what is permissible and prohibited is to follow the clear and established texts from the Quran and to draw on those well-known, consistently transmitted reports from the Prophet which have no chance of being conspired forgery, as well as reports from the righteous members of his Family that agree with the clear indications of the Book of God. In addition, we must follow the just and pious members of the Family of the Messenger of God. These are the compelling proofs for Muslims, and it is not permitted to follow other than these.64

The Zaydi imam al-Murtada Muhammad b. Yahya (d. 310/922) said:

Indeed many hadiths disagree with the Book of God most high and contradict it, so we do not heed them, nor do we use them as proof. But all that agrees with the Book of God, testified to by it as correct, is authentic according to us, and we accept it as evidence. And also what our ancestors narrated, father from son, from ‘Ali, from the Prophet, we use as proof. And what was narrated by the reliable (thiqat) people of the Prophet’s Companions, we accept and apply it. And what disagrees with [all] this we do not see as correct, nor do we espouse it.65

Zaydis feel that there is undeniable evidence from the Quran and Sunna that ‘Ali and his descendants through the Prophet’s daughter enjoy unique virtues and leadership responsibilities. The legal rulings and consensus of scholars from the Family of the Prophet and the hadiths they transmit are authoritative for Zaydis. Like Imamis, Zaydis accept the mursal hadiths of imams (their narrations from the Prophet without citing a full isnad). In addition, as Imam Sharaf al-Din (d. 965/1557–8) stated, whatever scholars from the Family of the Prophet declare to be authentic hadiths is so. Although Zaydis foreswear those who openly opposed the Family of the Prophet, they generally allow the narration of hadiths from Sunni transmitters either in order to use their hadiths as evidence against them or because those specific hadiths have been verified by Zaydi scholars. One of the Zaydi criticisms of the Sunni hadith tradition is the relatively small reliance on hadiths transmitted through the family of the Prophet. Zaydi scholars, for example, blame al-Bukhari for narrating hadiths via Kharijites known for their hatred of ‘Ali but not through the revered imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq.

Zaydi Islam also upholds a unique stance on the Companions of the Prophet. Both Sunni and Imami Shiite Islam espouse absolute positions – either anyone who saw the Prophet even for a moment was upstanding or only those who actively supported ‘Ali were. For Zaydis, only those individuals who enjoyed prolonged exposure to the Prophet and remained loyal to his teachings after his death are worthy of the title ‘Companion.’ Individuals known for impious behavior, like Walid b. ‘Uqba, or those who actively fought against ‘Ali, such as Mu‘awiya, are not considered to be Companions at all. Zaydis take Sunnis to task for naively believing that anyone who met the Prophet could serve as a reliable hadith transmitter.

Zaydis maintained this more cynical perspective in their approach to early Islamic history in general. The political agendas of Umayyad and Abbasid rule, they assert, left lasting affects on Sunni Islam. They believed that the Umayyads had encouraged the forgery of anti-Alid hadiths as well as hadiths praising other less worthy Companions. The Abbasids cultivated the four Sunni madhhabs as a means to stem any loyalty to the Family of the Prophet, making a dismissal of the Prophet’s Family a hallmark of early Sunni Islam.

As influential to their hadith worldview as their Alid loyalties is the Zaydi commitment to the Mu‘tazilite school of theology and legal theory. Like other Mu‘tazilites, Zaydis believe that passing the tests of the Quran and reason is essential for determining the authenticity of hadith. Zaydis often require hadiths to be massively transmitted (mutawatir) or accepted by the consensus of scholars in order to be used in defining theological stances. But Zaydis also accepted hadiths on these subjects if they were approved by imams. The Mu‘tazilite rejection of anthropomorphism has led Zaydis to dismiss any hadith that describes God in overly human terms in a manner that could not be interpreted figuratively. Zaydis thus hold that hadiths like the ones stating that when God sits on his throne it squeaks like a saddle or that Muhammad is physically seated next to God on His throne are elements of Jewish and Christian lore that crept into the Islamic tradition through early converts like Ka‘b al-Ahbar.

The specifically Zaydi corpus of hadith is not as vast as either its Sunni or Imami Shiite counterparts. Its foundation is the Musnad of Zayd b. ‘Ali, which Zaydis claim to be the first book of hadiths written in Islam. It consists of 228 Prophetic hadiths, 320 reports from ‘Ali, and two reports from al-Husayn.66 Interestingly, many of the reports that Zayd narrates from his great-great grandfather ‘Ali appear as Prophetic hadiths in Sunni collections, such as the statement ‘The ulema are the heirs of the prophets. The prophets have not left a dinar or a dirham; rather, they left knowledge as an inheritance among the scholars.’67 Small amali, or dictation session, collections are very important in Zaydi Islam. Two famous ones are the amali of Abu Talib Yahya b. Husayn (d. 424/1033) and the amali al-sughra of Imam al-Mu’ayyad Ahmad b. al-Husayn al-Haruni (d. 421/1030). Another central work of hadith and law is the Jami‘ al-kafi of Abu ‘Abdallah Muhammad b. ‘Ali of Kufa (d. 445/1053–4).

Zaydis have generally drawn heavily on what we would define as the Sunni and Imami Shiite hadith reservoirs. Zaydi scholars regularly quote mainstream Sunni hadith collections as well as Imami works like the Usul al-kafi of al-Kulayni and the Nahj al-balagha of al-Sharif al-Radi, choosing material that they feel conforms to Zaydi doctrine. Zaydis can draw from such eclectic sources because of the intermediate position that their school occupies between Sunni and Imami Shiite Islam. Sunni scholars that the Sunni tradition saw as favoring or cultivating a great affection for the Family of the Prophet are seen by Zaydis as pious Shiites. The Zaydi scholar Sarim al-Din al-Waziri (d. 914/1508) thus declares that al-Nasa’i, who refused to write a book on the virtues of Mu‘awiya, al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, who declared the hadith of Ghadir Khumm to be sahih, and al-Tabari are all Shiites.68

The most important works of Zaydi hadith criticism appeared relatively late in Islamic history. Although these books draw at great length from earlier works of Zaydi hadith scholarship, few early works have survived intact. Zaydis view Ibn ‘Uqda (d. 332/944) (mentioned above as an Imami hadith critic, an indication of how elastic these sectarian identities could be) as the progenitor of their formalized study of hadith transmitters and criticism, citing his many lost books on the various students who transmitted from imams like Ja‘far al-Sadiq.69 The most frequently cited later works are al-Falak al-dawwar fi ‘ulum al-hadith wa al-fiqh wa al-athar (The Orbiting Heavenly Body on the Sciences of Hadith, Reports and Law), an ambitious one-volume work by the fifteenth-century scholar Sarim al-Din Ibrahim al-Waziri that lays out the basics of the Zaydi world-view, hadith criticism, important transmitters, and stances on major legal issues, as well as the Kitab al-I‘tisam of al-Qasim b. Muhammad b. ‘Ali (d. 1059/1620).

A further study of Shiite hadiths should begin with more involved reading on Shiism in general. Heinz Halm’s Shi‘ism (2nd ed., New York, 2004) is both succinct and comprehensive, discussing all the branches of Shiism. Moojan Momen’s An Introduction of Shi‘i Islam (New Haven, 1985) is a classic guide to Imami Shiism in particular. For specific discussions of Shiite hadith, see Etan Kohlberg’s chapter ‘Shi‘i Hadith’ in The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature: Arabic Literature until the End of the Umayyad Period (London, 1983) as well as his article ‘Al-Usul al-Arba‘umi’a’ in Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 10 (1987). Ron P. Buckley’s article ‘On the Origins of Shi‘i Hadith’ in Muslim World 88, no. 2 (1998), Robert Gleave’s ‘Between Hadith and Fiqh: The “Canonical” Imami Collections of Akhbar’ in Islamic Law and Society 8, no. 3 (2001), and Andrew Newman’s The Formative Period of Twelver Shi‘ism: Hadith as Discourse between Qum and Baghdad (Richmond, Surrey, 2000) are also very informative. Anyone interested in the early period of Shiism under the imams should consult Hossein Modaressi’s encyclopedic Tradition and Survival: A Bibliographical Survey of Early Shi‘ite Literature Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oneworld, 2003). For a summary of the circumscribed Ismaili hadith tradition, see Ismail Poonwala, ‘Hadith Isma‘ilism’ in the Encyclopedia Iranica.

For an analysis of Imami Shiite hadith criticism, see Asma Afsaruddin’s article ‘An Insight into the Hadith Methodology of Jamal al-Din Ahmad b.Tawus,’ Der Islam 72, no.1 (1995): 25–46.

For original works of Shiite hadith scholarship in translation, see a fascinating section of al-Kulayni’s Al-Kafi, trans. Muhammad Hasan al-Rizvani (Karachi, 1995) and ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Fadli and al-Shahid al-Thani, Introduction to Hadith, including Dirayat al-Hadith, trans. Nazmina Virjee (London, 2002).

1 Muhammad b. Ya‘qub al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi (Karachi), p. 150.

2 Ibid., pp. 158–160.

3 Ibid., pp. 136–137.

4 Heinz Halm, Shi‘ism, p. 36.

5 Ibid., pp. 36–37.

6 Ibid., p. 42.

7 Etan Kohlberg, ‘Shi‘i Hadith,’ p. 301.

8 Hossein Modaressi, Tradition and Survival, p. 81.

9 Kohlberg, ‘Shi‘i Hadith, pp. 300–301.

10 Ibid., p. 306.

11 Modaressi, Tradition and Survival, p. 228.

12 Ibid., p. 147.

13 Kohlberg, ‘Shi‘i Hadith,’ p. 304.

14 Kohlberg, ‘Al-Usul al-Arba‘umi’a,’ p. 133.

15 Ibid., p. 170.

16 Ron Buckley, ‘On the Origins of Shi‘i Hadith,’ p. 182.

17 Robert Gleave, ‘Between Hadith and Fiqh: The “Canonical” Imami Collections of Akhbar,’ p. 351.

18 Al-Kulayni, al-Usul al-kafi, vol. 1, pp. 45–49.

19 Ibn Babawayh, Man la yahduruhu al-faqih, vol. 1, p. 71.

20 Halm, p. 50.

21 Gleave, p. 352.

22 Kohlberg, ‘Al-Usul al-Arba‘umi’a,’ p. 135.

23 See al-Dhahabi, Mizan al-i‘tidal, vol. 3, p. 124.

24 Devin Stewart, ‘The Genesis of the Akhbari Revival,’ p. 188.

25 Kohlberg, ‘Shi‘i Hadith,’ p. 306.

26 Kohlberg, ‘Al-Usul al-Arba‘umi’a,’ p. 137.

27 Ibid., pp. 139–140.

28 Ibid., p. 141.

29 Halm, p. 58.

30 Al-Kulayni, al-Kafi (Karachi), pp. 129–130.

31 Kohlberg, ‘Al-Usul al-Arba‘umi’a,’ pp. 139–141.

32 Ahmad b. ‘Ali al-Najashi, Rijal al-Najashi, vol. 1, pp. 225, 240.

33 Gleave, p. 372.

34 ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Fadli and al-Shahid al-Thani, Introduction to Hadith, including Dirayat al-Hadith, p. 25.

35 Ibid., p. 34.

36 Ibid., p. 26.

37 Ibid., p. 25.

38 Cf. Kohlberg, ‘Shi‘i Hadith,’ p. 303.

39 Halm, p. 51.

40 Al-Fadli and al-Thani, p. 26.

41 Al-Kulayni, al-Kafi (Karachi), p. 179–180.

42 Buckley, p. 168.

43 Al-Dhahabi, Mizan al-i‘tidal, vol. 4, p. 357.

44 Sahih al-Bukhari: kitab fada’il ashab al-Nabi, bab manaqib qarabat Rasul Allah.

45 Buckley, p. 168.

46 Ibn Abi Ya‘la, Tabaqat al-hanabila, vol. 2, p. 156.

47 Kohlberg, ‘Shi‘i Hadith,’ p. 299.

48 Ibid., p. 303.

49 Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi (Karachi), p. 147.

50 Ibn Babawayh, amali al-saduq, p. 7.

51 Al-Dhahabi, Mizan al-i‘tidal, vol. 2, p. 492; al-Hakim, al-Mustadrak, vol. 3, p. 154.

52 Ibn Babawayh, amali, p. 9; Abu Nu‘aym al-Isbahani, Hilyat al-awliya’ fi tabaqat al-asfiya’, vol. 6, p. 120.

53 Cf. Halm, pp. 58–59.

54 ‘Musnad ‘Ali Rida,’ p. 446.

55 Al-Rafi‘i, Al-Tadwin fi akhbar Qazwin, vol. 3, p. 482.

56 Kohlberg, ‘Al-Usul al-Arba‘umi’a,’ pp. 130–131.

57 Taj al-Din al-Subki, Tabaqat al-shafi‘iyya al-kubra, vol. 1, pp. 314–316.

58 Al-Dhahabi, Mizan al-i‘tidal, vol. 1, pp. 137–138.

59 Kohlberg, A Medieval Muslim Scholar at Work, pp. 324–325.

60 Ibn Babawayh, amali, p. 2.

61 Nasir al-Din Qazvini, Ketab-e naqd, pp. 576–578.

62 The hadith of ‘Ali’s name being written on the doorway to Paradise does, however, appear in the Kitab fada’il al-sahaba of Ahmad b. Hanbal; Ibn Hanbal, Kitab fada’il al-sahaba, vol. 2, p. 665.

63 Muhammad Yahya al-‘Azzan, Al-Sahaba ‘ind al-zaydiyya, p. 56.

64 ‘Abdallah Hamud al-‘Izzi, ‘Ilm al-hadith ‘ind al-zaydiyya wa al-muhaddithin, p. 42.

65 Al-Miswari, Al-Risala al-munqidha, pp. 60–62.

66 Al-‘Izzi, ‘Ilm al-hadith ‘ind al-zaydiyya, p. 271.

67 Zayd b. ‘Ali, Musnad Zayd b. ‘Ali, p. 383.

68 Sarim al-Din Ibrahim al-Wazir, Al-Falak al-dawwar fi ‘ulum al-hadith wa al-fiqh wa al-athar, pp. 69, 222.

69 Al-‘Izzi, ‘Ilm al-hadith ‘ind al-zaydiyya, p. 225.