CHAPTER TWO

The Power of Narratives and the Imagination

HOW DID THE NARRATIVE OF WHITE SUPREMACY and the social imagination of “otherness” develop in Western society? How do dysfunctional narratives emerge from a social reality and in turn shape that reality? As social reality gets constructed, the social imagination plays a significant role in the formation and sustaining of that social reality. In a society with significant religious influences, the theological imagination can impact the social imagination. The Doctrine of Discovery presents an example of the impact of a dysfunctional Christian theological imagination on social reality.

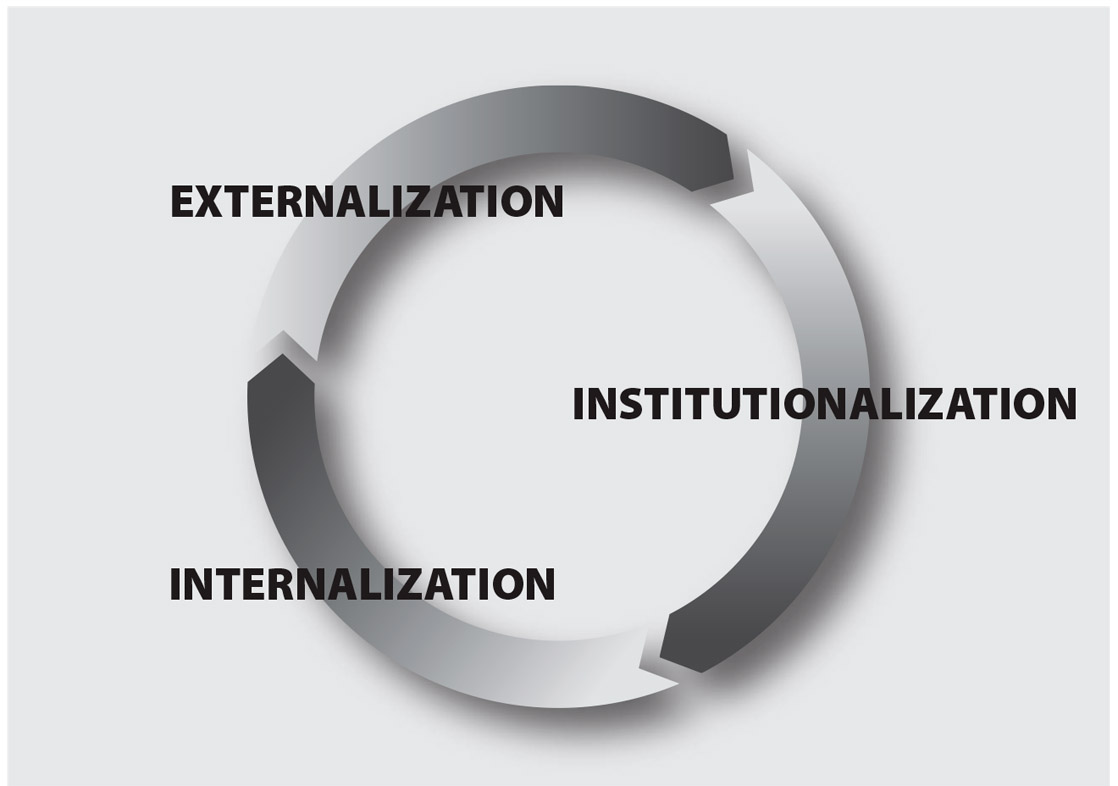

Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann present a theory on the construction of social reality.1 They argue that social systems are formed through the interaction of multiple factors including externalization, institutionalization, and internalization. Individuals entering a social system contribute to that system through the externalization of that individual’s identity and values. The individual’s values and perspectives are externalized into the system, helping to shape the system.

The full construct of a social system, however, is not simply attributable to the influence of individuals. Berger and Luckmann assert that institutions can take on a life of their own through the process of institutionalization. The social system becomes an external object that is institutionalized and now begins to exhibit a value system that has moved beyond the specific values of the individuals who may have initially shaped the system.2 The institution has the capacity to outlast the individuals that originally established the system.

In turn, the institution begins to influence individuals within the system through the process of internalization. This institutionalization of the social system helps create an external objective reality, and individuals within the system now begin to take on and internalize the values of that reality. The process of internalization completes the cycle. The institution has fully moved beyond the influence of the individuals that initially created the system. And the institutionalized system now has the power and capacity to perpetuate itself with continued influence upon anyone entering the system.3

The social construction of reality reveals the power of internalization. Dysfunctional messages generated by the dysfunctional system impact those within the system. Even individuals who may have a strong sense of self-worth and who seek to retain their cultural identity may eventually succumb to the power of internalization, which can diminish both their self-worth and their cultural identity.

One Sunday I (Mark) was teaching in one of the churches on our reservation and I concluded with a call to bring the gospel to the ends of the earth. I specifically challenged the church to consider participating in missions outside of our reservation. After the service, I was approached by one of the grandmothers of the church. She appreciated my message but wanted to remind me that while such a call to missions might be possible for someone who had earned a college degree, she and many other members of the church never went to college. They didn’t have degrees and therefore could not become missionaries.

In the Western mission model, which is rooted in the Doctrine of Discovery, the primary role for the “heathens” is to simply receive the message and the charity of their benevolent, generous, and well-educated missionaries. If they show real potential and demonstrate extraordinary ambition, they might be able to work their way up to a support role, but they will never become full partners in the gospel. The message that was externalized by the early missionaries became institutionalized in the churches throughout the reservation and is still being internalized by the congregants. In a similar fashion, the Doctrine of Discovery emerged from an externalized worldview by the European Christian powers that became institutionalized in the European colonial powers and would become internalized by the world conquered by the European powers.

THE POWER OF THE IMAGINATION

The human imagination serves as a powerful tool in the construction of social systems. Imagination shapes the worldview and the subsequent actions of an individual and can be internalized in the individual within social reality. In the same way, the social imagination has the capacity to profoundly influence and shape society. The construction and preservation of social reality depends on the power of the imagination.

The formation of the imagination emerges from the way individuals and communities process social reality and how they are shaped by social reality. The social imagination helps us to make sense of the world around us and allows us to consider possibilities in the systems and structures where we dwell. Sociologist C. Wright Mills notes that “the sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. . . . It is by means of the sociological imagination that men now hope to grasp what is going on in the world, and to understand what is happening in themselves as minute points of the intersection of biography and history within society.”4 William Cavanaugh adds that “the imagination of a society is the sense of what is real and what is not; it includes a memory of how the society got where it is, a sense of who it is, and hopes and projects for the future. . . . [it] is the condition of possibility for the organization and signification of bodies in a society.”5 Therefore the social imagination possesses the power to shape and influence society.

Differentiated from the social imagination, the theological imagination has the power to generate a view of the world that expands beyond the limitations of one’s own immediate reality. The possibility of transcendence, an experience beyond normal physical human capacity, is offered by the social imagination and may be buttressed or furthered by the theological imagination.

Willie Jennings asserts that theology is the “imaginative capacity to redefine the social.”6 Walter Brueggemann calls the church to a theology that engages the prophetic imagination. Brueggemann believes that “the task of prophetic ministry is to nurture, nourish, and evoke a consciousness and perception alternative to the consciousness and perception of the dominant culture around us.”7 The power of theology is the power to expand our imagination, so theology offers the possibility of a prophetic imagination that can transform the individual and society.

Christian theology can contribute significantly to the development of a transcendent imagination, which can provide a positive function in broadening the imaginative capacity of the individual. However, this capacity for transcendent vision can also lead to a sense of arrogance and privilege by limited human beings. The belief that the theological imagination allows the Christian to connect with the divine can lead the Christian to assume that they speak from a position of privilege, chosen and preferred by God, and that the Christian has the capacity to know what is best for the rest of the world.

The reality of a broken world and broken systems within the world, therefore, means that Christians often engage in a dysfunctional theological imagination. As Jennings asserts, “Christianity in the Western world lives and moves within a diseased social imagination.”8 The diseased social imagination of the United States has been shaped by the dysfunctional theological imagination of the Western world known as the Doctrine of Discovery, which has resulted in the formation of the dysfunctional social systems of the United States. These dysfunctional systems find fuel from the dysfunctional narratives of our society, which are shaped by the social and theological imagination.

On June 4, 2017, a terror attack occurred in London, claiming seven lives and injuring nearly fifty people. A few hours later evangelical leader Franklin Graham posted the following to his public Facebook account:

The threat of Islam is real. The threat of Islam is serious. The threat of Islam is dangerous. . . . We need to pray that God would give our President, our Congress, and our Senate wisdom—and the guts to do what is right for our nation.9

Franklin Graham identified Muslims and the entire religion of Islam as the enemy. Graham urged prayer to God not for the victims or even for the church but for his own nation-state, for his President and political leaders to have the “guts to do what is right for our nation” (emphasis ours). Graham is identifying his own country as Christian and the war as religious. He aligns the United States on the side of God and of the good, while relegating Muslims and all of Islam on the side of evil. His rhetoric of moral superiority and the mindset of religious supremacy is similar to the imagination of the leaders of previous iterations of Christendom.10 Franklin Graham reveals a disturbingly dysfunctional social imagination of European/American superiority buttressed by his dysfunctional theological imagination of European-American Christian supremacy.

THE POWER OF METAPHORS

Another layer of analysis for the power of the imagination is offered by communication scholar George Lakoff. Lakoff asserts that certain forms of communication, particularly metaphors, impact the formation of social reality and the functioning of institutions within society. Lakoff argues that the traditional view of reason is that it is abstract and disembodied. It “sees reason as literal, as primarily about propositions that can be objectively either true or false.” But the new view sees reason as having a bodily, even imaginative, basis. In the new view, “metaphor, metonymy, and mental imagery” are central to reason rather than peripheral.11 The imagination that can shape the social system is more deeply impacted by metaphors than by logical reason. Despite the assertion of the Enlightenment, human beings are more than simply chemical responses to a stimulus. We not only respond with reason in our minds, but we also respond with the body and with feelings emanating from the mind and body.

Jesus understood the power of metaphors in his use of parables. Jesus did not simply list the aspects of God’s character but appealed to people’s imagination by telling parables about how God is like a father—not just any father, but a rich, generous, and forgiving father. He did not talk about heaven and the kingdom of God in stale, abstract terms. He compared finding the kingdom of God to the experience of finding a lost coin or a treasure buried in a field. Jesus also talked bluntly not only about his own impending crucifixion, but about how his followers must also pick up their cross and follow him. Therefore, he frequently used metaphorical communication and appealed to people’s imagination regarding the character of God and the rewards of heaven because he understood that pure logic and reason alone would not be enough to get his followers through persecution.

While Jesus used metaphor to spark a kingdom imagination to endure persecution, Satan also stirred a fearful imagination. In Luke 4:13, after Jesus resisted the temptations of Satan, we are told that the devil “left him until an opportune time.” In Luke 22, just before his arrest, Jesus told his disciples, “Pray that you will not fall into temptation” (v. 40). He then went a stone’s throw beyond them and “being in anguish” over the prospect of his coming persecution, he prayed so earnestly that “his sweat was like drops of blood falling to the ground” (v. 44).

In the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus realized the temptation to have the cup pass from him and not suffer and die on the cross. In this, Satan found an opportune time to tempt Jesus. Temptation may have been easier to resist when Jesus was standing on a high mountaintop discussing a persecution years away, but a more opportune time was the night before the persecution, when the soldiers were walking into the garden to make an arrest. But even then, Jesus prayed to his Abba and resisted the temptation to flee persecution and settle for an earthly kingdom. Jesus worshiped God alone by surrendering his will and saying to his Father, “Not my will, but yours be done” (Luke 22:42).

Throughout the twenty-first century, many white Christian leaders in the US have frequently expressed the anxiety that the United States of America has lost its Christian values, even fearing that Christians in our country are facing persecution. This embedded fear and anxiety often drives many Christians in the US to seek out comfort through partisan politics and to embrace the heresy of Christendom. Successful Christian leaders will often embrace partisan political leaders that tap into the metaphors which serve the retention of Christian empire.

In 2016, Donald Trump won the presidential election with overwhelming support from white Evangelicals and white Catholics. Many questions were raised as to how Trump won the support of the conservative Christian right. This was a candidate who stormed onto the political scene by asserting the unfounded accusations of the birther movement. This was a candidate who at his first campaign event said about immigrants from Mexico: “They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists.”12 This was a candidate who, on the stage of a conservative Christian college in Iowa, bragged that he could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue in New York and shoot somebody and not lose a single voter. This was a candidate who was caught on a live mic bragging that his celebrity and fame gave him the right to sexually assault women. This was a candidate who was unrepentant of his multiple affairs. This was a candidate who on national radio bragged about his sexual exploits and even allowed the host, Howard Stern, to refer to his daughter as “a piece of ass.”13 This was a candidate who claims to be a Christian but, when asked at the Family Leadership Summit in July 2015 if he had ever asked God for forgiveness, responded, “I am not sure I have, I just go and try to do a better job from there. I don’t think so. I think, if I do something wrong, I think I just try to make it right. I don’t bring God into that picture. I don’t.”14 Very little about Donald Trump reflects either a desire for the high moral standards associated with Christian life and practice or the humility of a hurting person grateful for the forgiveness and healing mercies of Christ.

Trump himself revealed his playbook to garner the vote of white Evangelicals in an interview with the Christian Broadcast Network on October 27, 2016, where he stated:

We’re doing very well with evangelicals. And if they vote we’re going to win the election. And we’re going to have a great Supreme Court. And we’re going to have religious liberty. Because religious liberty, let’s face it. I saw a high school football coach the other day and they were praying before the game. You know they’re going into combat, they’re in the locker room praying, and, I think they’re going to fire him. And. You know they suspended him. I think they want to fire him. Whoever heard of a thing like this. And I always say to you, we’re going to all be saying Merry Christmas again. But the truth is religious liberty is under tremendous stress.15

While Trump raised the specter that “religious liberty is under tremendous stress,” he had no qualms enacting a ban on Muslims entering the United States and approving the Dakota Access pipeline that ran through lands considered sacred to the Dakota people.

When Trump and the religious right use the term “religious liberty,” what is actually meant is “Christian liberty.” Donald Trump promised religious liberty by claiming that his election would allow Americans to “all be saying Merry Christmas again.” Trump used metaphor and mental imagery to appeal to the dysfunctional imagination of the voters. He exacerbated the church’s fears of persecution in order to tempt the faithful away from the difficult teachings of Christ and towards the ease and temporal safety found in the heresy of Christian empire.

Lakoff claims “evidence that the mind is more than a mere mirror of nature or a processor of symbols, that it is not incidental to the mind that we have bodies, and that the capacity for understanding and meaningful thought goes beyond what any machine can do.”16 The individual imagination, the social imagination, and the theological imagination can profoundly shape and influence social systems. These imaginaries, however, are not simply formed by linear and reasonable proposition. Instead, Lakoff points towards the possibility of the imaginary and narratives that govern social systems being formed by feeling, emotions, and bodily experience.

For the church, the social imagination can be influenced by the theological imagination, which can generate an even deeper embodied experience or feeling. The theological imagination can have a logical component, but it can also shape and be shaped by emotional experiences. This interconnection is found in the power of the collective imagination. Contrary to our assumptions, both of these imaginations (social and theological) may not be rooted in the rational order. It is the arrogance of Western theology to assume that all of our theological musings are rooted in rationality and logic and therefore must not be susceptible to dysfunction. However, a diseased theological imagination can put forth a dysfunctional expression that ultimately forms a dysfunctional social imagination. The diseased theological imagination (such as Christendom, the Doctrine of Discovery, and the myth of Anglo-Saxon purity) contributed to a dysfunctional social imagination (white supremacy) that has perpetuated unjust leaders, systems, and structures.

THE POWER OF NARRATIVES

Lakoff’s explanation of the use of metaphor and its impact on the social imagination takes on another layer of meaning with the analysis offered by Walter Wink. The human imagination has the great power to generate, foster, and perpetuate existing systems and structures through the individuals within the system. The social and theological imagination can arise from individuals and from the system itself. The social theological imagination can have a direct effect on the system of the institution and subsequently impact the individuals within the institution. Wink uses the language of “the powers that be” to explain how systems and structures can take on a life of their own and influence both the system and individuals through the power of mediating narratives.

To Wink, the powers that be “are more than just the people who run things. They are the systems themselves, the institutions and structures that weave society into an intricate fabric of power and relationships. These Powers surround us on every side. They are necessary. They are useful. . . . But the Powers are also the source of unmitigated evils.”17 The captivity to individualism in the West leads many to reject the possibility of institutions and systems inflicting social harm that requires a social response.18

Scripture testifies to the reality of systems and structures beyond the personal, individual, and the material. When John 3:16 speaks of how God loves the world, it speaks of the cosmos, the systems and structures of our social reality which impact our lives. Ephesians 6:12 is even more explicit in revealing a power beyond the individual and material by stating that “our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark work and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realm.” Powers, according to the Bible, can operate in evil ways in the larger context of the cosmos.

Wink claims that “greater forces are at work—unseen Powers—that shape the present and dictate the future.”19 These powers reflect a spiritual reality. “The spirituality that we encounter in institutions is not always benign. It is just as likely to be pathological. . . . Corporations and governments are ‘creatures’ whose sole purpose is to serve the general welfare. And when they refuse to do so, their spirituality becomes diseased. They become ‘demonic.’ ”20 These systems with a diseased spirituality are shaped and influenced by narratives that are also profoundly diseased. Narratives, therefore, have significant influence on systems and structures as well as on the social imagination. Narratives are also not neutral and have the capacity to express evil intention and influence on social reality.

Walter Wink postulates that social structures need mediating narratives in order to sustain dysfunctional systems. For example, the dysfunctional system of Western society needs the myth of redemptive violence to sustain its authority and legitimacy over its residents: “Unjust systems perpetuate themselves by means of institutionalized violence.”21 Violence can now be justified and redeemed. Something that inherently brings harm is now considered to bring about healing. The entirety of the system has become so corrupt that it perpetuates dysfunction.

The dysfunctional narrative of redemptive violence has taken firm root in the social imagination of America. America assumes it has the capacity to use violence in redemptive ways while the rest of the world does not have that capacity. Walter Brueggemann points out that there is “a militant notion of US exceptionalism, that the US is peculiarly the land of freedom and bravery that must be defended at all costs. It calls forth raw exhibits of power, sometimes in the service of colonial expansionism, but short of that, simply the strutting claim of strength, control, and superiority.”22 The myth of redemptive violence allows Americans to see themselves as having superior intellect and value and therefore the ability to handle weapons capable of incredible violence in an appropriate manner. The dysfunctional social imagination of American exceptionalism informs the mediating narrative of the myth of redemptive violence.

Currently, there is appropriate concern regarding weapons of mass destruction in the hands of the wrong people. Specifically, there is concern that Kim Jung Un of North Korea possesses nuclear capabilities. It is self-evident and logical to deny a WMD to the North Korean dictator. Kim Jung Un should not have nuclear weapons. However, there is no conversation on who else should be allowed to have nuclear weapons. For example, if you were to walk into a room where five people possessed AR-15 rifles, you should be legitimately concerned about the guy in the corner who just got the weapon and is muttering to himself trying to figure out how that weapon works. You don’t want that guy to have a weapon of violence.

But the person you should be most worried about in the room is the one guy who has the weapon and has used the weapon to kill people (even civilians) in the past. That guy not only knows how to use the weapon, he has actually used it. While Kim Jung Un’s possession of a weapon of mass destruction is a scary prospect, we never consider how the rest of the world might view the one nation on the entire planet that has used a weapon of mass destruction not just once, but twice, on a civilian population. The social imagination of white American Christian exceptionalism feeds the narrative of the myth of redemptive violence, which continues to perpetuate fallen and broken systems.

The challenge to a fallen system requires confrontation on the structural level and of the mediating social narratives that drive those dysfunctional systems. “The task of redemption is not restricted to changing individuals, then,” Wink explains, “but also to changing their fallen institutions. . . . Redemption means actually being liberated from the oppression of the Powers, being forgiven both from one’s own sin and for complicity with the Powers.”23 The corrupt system that emerges from a diseased social imagination now results in a broken system that perpetuates a dysfunctional narrative. The problem of the Doctrine of Discovery is that it affirms the perspective of a diseased social and theological imagination. It established the false notion of a more ethnically pure, European Christian supremacy, and today it furthers the mythology of American exceptionalism, which is rooted in the blatant lie of a white racial supremacy.

The mediating narratives rooted in a dysfunctional imagination that fuel the social systems provide a locus of evil that must be confronted, and evil must be confronted in its proper geography.24 Because mediating narratives provide the fuel for dysfunctional systems, they can hold a power that we can oftentimes overlook. For instance, if there is an overriding narrative of white supremacy that fuels a dysfunctional system, the demise of that system does not necessarily mean the end of the narrative.

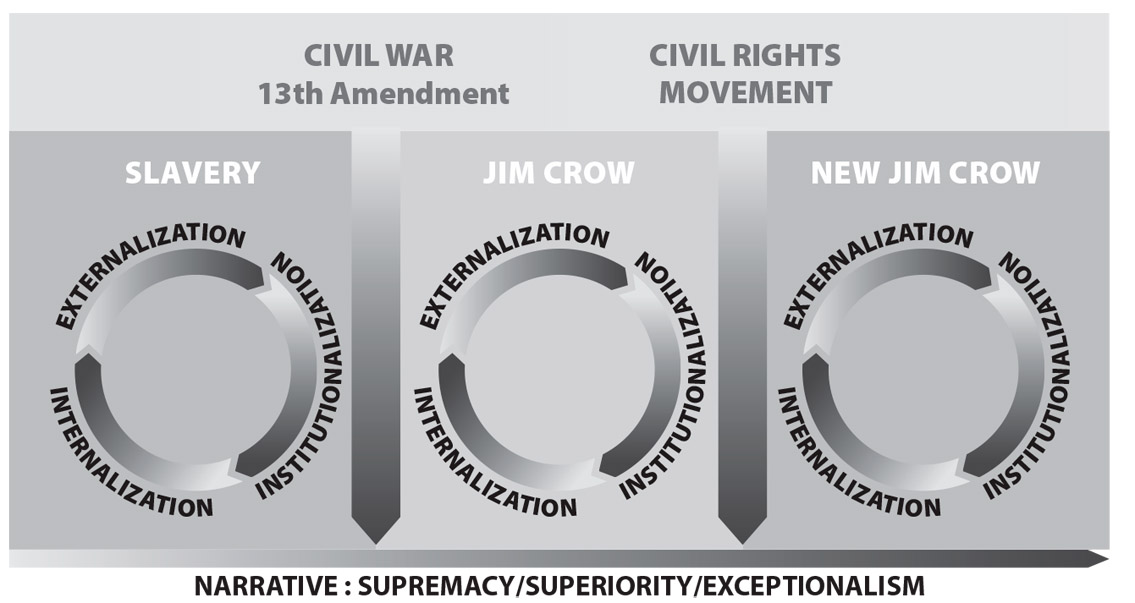

In the United States, the narrative of white supremacy is a central theme that fuels our dysfunctional systems. The horrid institution of slavery fulfilled the narrative of white supremacy. Yet even after the institution of slavery was abolished, the dysfunctional narrative of white supremacy continued; therefore a new dysfunctional system of Jim Crow laws took the place of slavery. When the dysfunctional system of Jim Crow was overturned through the Civil Rights movement, the mediating narrative of white supremacy remained, and Jim Crow was replaced with the New Jim Crow, a system of mass incarceration and disenfranchisement that allowed the narrative of white supremacy to continue.

The power of the mediating narrative is the ability to create new systems to take the place of old systems that still function to further the diseased imagination and corresponding mediating narrative. (See figure 2.2.) The power of narratives should not be underestimated as they form and shape public opinion and response in ways that logic and reasoning may not.

Systems and structures will seek to maintain and preserve themselves. Systems and structures, therefore, will form metaphors, narratives, and imaginaries that help to sustain the values that have become embedded within the system. The Doctrine of Discovery serves the social system of the Western world. The dysfunctional imagination that shapes and perpetuates the Doctrine of Discovery helps maintain the social construct of Western reality, even when the system operates in a dysfunctional fashion. The dysfunctional imagination forms dysfunctional narratives that help to sustain the dysfunctional system.

In the work of healing brokenness in the world, the failure to recognize the power of narratives could derail any progress. Attempts to simply change the individual and to rid individual prejudices prove to be insufficient in this endeavor. Even attempts to change systems and structures may not be sufficient as new systems and structures take the place of old ones. Narratives, formed by the social and theological imagination, are the powers and principalities that must be addressed so that all levels of social reality are confronted. The Doctrine of Discovery, rooted in fifteenth-century theological dysfunction, is one of the most influential yet hidden narratives in American society that continues to impact social reality in American society well into the twenty-first century.