FOUR Naturalists in the Crow’s Nest

WHAT THE WHALEMEN KNEW

For all the importance of Mitchill’s testimony, however, the jury had other witnesses to consider, several of whom could claim a very different but no less compelling expertise where the cetes were concerned: they had actually seen living whales up close on the high seas, had killed them there, and had cut deep into their still-quivering flesh. Two of the witnesses called in the trial—Captain Preserved Fish (whose name, predictably, attracted the mirth of several commentators) and the sailor James Reeves—had been on whaling voyages and were therefore the only participants in Maurice v. Judd who had confronted the creatures at issue in the case alive and at close quarters. Unfortunately for those seeking a firm footing in such “practical” cetology, the two whalemen disagreed emphatically on the question before the court.

Captain Fish, who had spent ten years in the whaling business and had risen to be master of a vessel, hailed from New Bedford, the Massachusetts city that was in those very years displacing Nantucket as the gravitational center of the whaling industry in the United States.1 Invoking his hands-on expertise, Fish boasted a total of more than thirty years of experience with whales and the commercial products derived from them, and he took the stand for the defendant, Judd, announcing to the court that, in his experience, “the whale had no one character of a fish, except its living in the water.” To emphasize the point, Fish underlined the signal difference: “Whales must breathe the atmospheric air; they may live for half or three quarters of an hour under water, but must then come up to breathe the air again.” In fact, Captain Fish gestured in the same direction as Mitchill, likening the cetes to human beings: “They [whales] would drown in the water, as much as a man would, if they were tied or kept by any means under water.”2

Cross-examination of Fish also fell to Sampson, who opened with a dramatic ploy: asking whether the common character of whale and fish could not be extended beyond mere place of habitation (indeed, extended to include almost exact identity of shape), Sampson approached the witness with a printed picture, an engraving of a whale, which he presented as clear evidence that whales were exceedingly fish-like in form.3 The witness, taking the sheet, disavowed the rendering, declaring that the image did not look at all like an actual whale:

Q: Has it no resemblance?

A: Very little.

Q: If a whale be not like that, can you say any thing to which it is more like?

A: It is very like itself; its tail differs from all other fish. The tail is flat, and it swims like a man.

When challenged on the manner of its locomotion (did the cetes not have fins like the Pisces?), Fish asserted that the fins of whales were more like “arms.” This tentative move onto the terrain of comparative anatomy was instantly and aggressively parried by Sampson, who was obliged to grant the whaleman a certain latitude when dealing with the appearance of the living creatures at sea, but who smelled weakness on matters of book-zoology:

Do you profess to understand the interior structure of these animals? Have they shoulder blades? Have they the joints and bones which belong to the upper limbs of man?4

For instance, was Captain Fish familiar with the terms “Scapula, humerus, radius, ulna, carpus, postcarpus, phalanges, &c. &c.?” Was he prepared to say if the structure of the whale’s fins was conformable to such nomenclature? Fish demurred on these technicalities, but he stood his ground, asserting that the difference in the directions of the tails indicated that whales were not fish. What about porpoises, then? They were emphatically not fish either, declared the captain: porpoises and whales together, he announced triumphantly, “are all of the order of mammalia.”

But by no means would Sampson allow the captain to have this incantatory taxonomic neologism (as if the word alone could, like a charm, resolve the matter): “From what philosopher do you borrow this classification, and this term of the mammalia?” Sampson demanded. To which Fish replied, “I have my information from the Encyclopedia.”

That middlebrow reading would not help him reply to the barrage of probing questions that followed: Were monkeys “mammals”? What did the term mean? Whence was it derived? What other animals did it include? Why? Sampson thus drove the captain grudgingly back onto his original position: whales weren’t fish because they breathed air, though (when pressed) Captain Fish was obliged to acknowledge that they could breathe with their mouth underwater, as long as their “nose” broke the surface. He was dismissed.

The other whaleman, James Reeves, was a before-the-mast sailor, and did not buttress his personal experience (he had made three whaling voyages, and “had seen the spermaceti whale fished and cut up”) with analytic distinctions borrowed from the library. Recalling his days at sea, Reeves explained that it was the common habit of whalemen to call their quarry “fish”: “When we hailed vessels,” he remembered, “we asked what luck or success; the answer was, one, two, or three hundred barrels, and sometimes one, or two, or three fish.”5 As for whether whales breathed air, Reeves denied that this was so obvious: he testified that he thought they might be able to breathe underwater, since “there is a hump, or a hole in the back of the head, where the water lodges till the animal comes up to empty it by spouting it out.”6 Who was to say it was impossible that they breathed water?7

Having thus bolstered the plaintiff’s case, Reeves came under cross-examination. If someone were to ask him for “fish oil,” Judd’s attorneys asked, what would he give them? Reeves had an easy answer: he would simply ask “what kind of fish oil do you want?” since, from what he understood, the “oil was named from the fish, as black fish, humpback, and whale oil.”8 As for the assertion that whale oil was not fish oil, it was news to him: “I never heard any distinction between fish oil and whale oil, as talked of here to day, but always thought that fish oil included them all.”9 But Reeves was also willing to admit that the trial—here tacitly alluding to the testimony of Dr. Mitchill and Captain Fish, both of whom preceded him on the stand—had wobbled his confidence. While yesterday, he explained, he would have gone to the market to fetch fish oil without much thought, he could no longer be quite so certain. In expressing his misgivings Reeves returned to the distressing formulation of Mitchill (“no more a fish than a man”), only to reassert the whaleman’s self-defining contrapositive: “It is no wonder if any man should have his doubts; I never had any before; I as much thought a whale was a fish from its swimming in the water as that I was a man from living out of it.”10

If the divergent opinions of James Reeves and Preserved Fish blunted the force of the taxonomic testimony from those who were, in a sense, most familiar with whales, their disagreement under oath provides an unusual glimpse into the natural-historical world of American whalemen, and offers telling insight into those men’s understanding of the animals they made their prey. At the very least these conflicting accounts suggest that it is time to revisit Elmo Paul Hohman’s venerable essay on “The Whaleman’s Natural History,” which departs confidently from the assertion that the nineteenth-century whaler “knew that the whale was a mammal and not a fish.”11 The transcript of Maurice v. Judd makes it clear that it was not so.

Having in the last two chapters considered at some length the whaleknowledge of two of the four categories of citizen alluded to by Sampson during the trial—“those who philosophize” (i.e., those informed by formal natural history, like Mitchill) and “everyone else” (i.e., common opinion among the court-watchers, jurors, and speakers of English in the city of New York)—we are now prepared to take up a third important group in Sampson’s human taxonomy: “those who fish” (and whale). What did nineteenth-century whalers know about whales? What was the “whaleman’s natural history,” if we must leave Hohman behind?

In pursuit of these questions, this chapter will take a departure from the Mayor’s Court in Manhattan, and move north, to the whaling ports of New England and the world of the whaling ships that moored there after plying distant waters. The aim? To understand how men like Fish and Reeves got their ideas about the anatomy and physiology of the cetes, and at the same time, by recovering this essential context, to deepen our appreciation of the place of whales (and Maurice v. Judd) in nineteenth-century America. Several caveats are required. First, as these two sailing-men’s conflicting accounts suggest, there was nothing homogenous about the world within the “wooden walls.” Rather, this world was a world indeed, as shot through with distinctions of rank, education, experience, and belief as any courtroom, parliament, or plantation. While William Scoresby Jr.—an English whaling captain in the first decades of the nineteenth century—could rise to be a Fellow of the Royal Society and publish extensively on meteorology and terrestrial magnetism (in addition to Arctic natural history), the taciturn master of a Provincetown “plum-pud’ner,” doing brief seasonal loops in the North Atlantic to pick up a few hundred barrels of whatever fat he happened on, might be barely literate.12 Moreover, this sort of synchronic diversity is itself overshadowed by yawning diachronic differences: the industry changed dramatically in size and character over the course of the century. Limiting ourselves to the United States—which achieved hegemony in the global pursuit of the great whales by the mid-century apex of the hunt—we can point to excellent econometric studies that trace the transformation of commercial whaling from a unique profit-sharing joint-stock enterprise, featuring relatively well-educated workers (in the 1820s), to a “sweated” industry of some brutality, increasingly dependent on foreign labor (by the 1850s and ’60s, shortly before the collapse of open-boat whaling); social histories chart the same evolution using different sources.13 In order to situate Maurice v. Judd in the world of the whalers, this chapter will range across the first half of the nineteenth century, but generalizations about what “whalemen” thought must always be hedged with care: a Cape Verde cabin boy in the 1850s? a Hawaiian boatsteerer in the 1840s? a Sabbatarian first mate from the Vineyard in the 1830s?

Such distinctions make no small difference in an investigation of vernacular natural history within this community. Not only did these diverse whalemen leave very disparate quantities and kinds of source material from which their ideas may be gleaned, they were also themselves very different readers, and thus gleaned their own ideas from very disparate sources. As we have seen, Captain Fish had familiarized himself (if not too thoroughly) with the same kinds of encyclopedic work out of which Sampson himself crammed for the trial. This was not unusual: many whaling logbooks provide ample evidence that whalemen, particularly masters and mates, read a great deal during their voyages, passing tracts around, and hailing passing ships for the purpose of swapping newspapers and pamphlets.14 Not all were as ambitious, perhaps, as Captain David E. Allen, of the bark Merlin, who ensured that his son, along on the voyage, made his way through both Hume and Macaulay in his off-hours, or Samuel T. Braley, master of the Arab out of Fairhaven, who wrote his wife in chagrin when a leak in his cabin soaked a $30 bundle of books for the voyage (including his Biography of Eminent Females); but the logbook entry by John Francis Allen for a drowsy Sunday aboard the Virginia en route to the “Jappan grounds” in 1843 captures the textual world of the whalemen: “men lying around deck and reading.”15 While literacy dropped off as the century progressed, it never fell below 75 percent of all hands, skilled and unskilled, and quite a few log-keepers (sometimes captains, but not infrequently lesser mates and experienced sailors as well) were sufficiently preoccupied with letters to be acutely self-conscious about their spelling and their penmanship: blank pages in the log of the Columbia display samples of the handwriting of Robert Gould, who proudly exemplified his skills both before and after he took lessons from “Dunton, Scribner.” And Joseph Bogart Hersey, keeping the log aboard the Esquimaux in 1843, annotated the word “punctilious” with a brief aside: “whether this word is spelled right, or not I do not know.” He also inserted an apology to his readers that the rocking ship made his hand less elegant than it would be ashore.16

These habits of reading and writing must enter any consideration of the whaleman’s natural history because they remind us that we cannot treat whalers’ ideas about these animals as purely the product of some immediate and unconditioned encounter with slippery whales on the high seas. As the surging importance of the industry occasioned a burst of popular and semipopular treatises on whales in the 1830s and 1840s—most of them by authors who claimed whaling experience—whalemen increasingly had access to texts that combined voyage narratives with natural historical commentary on marine mammals. These publications both emerged out of the world of the whaleships, and reentered that world as they were read by captains and seamen alike. Tracing such circulations is by no means an easy task, but given the importance of these books—particularly the two versions of the English whaler-surgeon Thomas Beale’s The Natural History of the Sperm Whale, the similar works of Henry William Dewhurst and Frederick D. Bennett (both also surgeons on English whaleships), and the very popular volume in Jardine’s Naturalist’s Library series, The Natural History of the Ordinary Cetacea or Whales—to nineteenth-century marine natural history, it is a necessary one.17

The last of these works, though apparently authored by an unsalted hand, was particularly concerned to draw whalemen into the service of formal cetology, noting that “[t]housands of mariners have captured and cut up whales” of which cabinet naturalists remained deeply ignorant, and thus:

We indulge the hope, that our little volume may become a vade mecum to many a mariner and fisherman, and that beguiling over it the tedium of a sea voyage, he may thereby be excited to improve some of those opportunities which frequently present themselves to him, though not to us; and that by making pertinent and judicious observations, he may thus add to the stock of our interesting and important information.18

Melville indeed depicted Ishmael as a reader of this little volume, but not one thereby transformed into a humble servant of museum zoologists; on the contrary, he found himself goaded to ungentle critique of museological sub-sub-librarians.19 Whether real tars (other than Melville) read their copies of The Ordinary Cetacea on the foredeck remains to be discovered, but it is certainly not impossible.20

In selecting source material out of which to build a picture of whalemen’s ideas about whales—manuscript logbooks and journals, sea chanteys and verse, published memoirs and voyage narratives—it is also essential to bear in mind that whaleman-authors themselves wrote for different readers, and adopted, with varying degrees of explicitness, different positions with respect to the world of book learning. By mid-century, for instance, when Melville crafted Ishmael’s wry and dismissive commentary on learned cetology, the collation of and commentary upon such material by whalemen with writerly aspirations was by no means unknown in the “literature of fact.” J. Ross Browne, a well-educated scrivener who knew shorthand, and who made a yearlong whaling voyage in the Bruce, 1842–1843, used the experience as the basis for his book Etchings of a Whaling Cruise, a text Melville knew well (he reviewed it on its appearance in 1846) and that may have inspired his meditations upon what would become Moby-Dick.21 Browne supplemented his volume with an appendix of excerpts from Beale, Shaw, and Hunter, explaining that while he made “no pretentions to scientific attainments,” he had ensconced himself in the Library of Congress after his return from the Indian Ocean to collect and study “the natural history of the whale” which had “engrossed no small share of my attention.” What was the whaleman’s view of book-learning, in his opinion? Browne put a wry comment into the mouth of one of his shipmates: “Cutting figures with the pen ain’t cutting blubber, by a considerable sight, is it?”22

Still, Browne was relatively deferential to natural-history authorities. Not so the prickly William M. Davis, an American whaleman active in the fishery in the boom years of the mid-1830s, but whose writings on the topic did not see light until later in the century, when his Nimrod of the Sea appeared in New York and London. Davis betrayed considerable familiarity with the published writings on marine natural history, and he made the disjuncture between such works and whalemen’s views an explicit theme of his book. For instance, pondering the ability of seabirds to stay aloft for weeks at a time, Davis hazarded several hypotheses, including a notion that they might have the bird-equivalent of the fish’s swim-bladder, filled with some particularly buoyant gas, enabling them to drift like dirigibles. He closed the ruminations as follows: “Here I leave it, with the remark that books in the libraries will show you what savants think on the points I have touched. I write only of what the sailor sees, thinks, and believes.”23 As if to highlight the spirited high-low engagement of blubber-hunters with latinate taxonomy, Davis narrated a forecastle debate about the feeding habits of the great whales. The exchange runs on for several pages, and combines vaudeville-esque character comedy with recollections from Pliny and annotations from writings in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.24 This excerpt gives a flavor of the section:

The bow-oarsman, myself, who had been talking, now continued: “With all respect for your extreme ugliness, my beloved Benjamin, I reiterate that the right-whale feeds on medusae, and other minute forms of animal life; and the spermaceti feeds on octopods, cephalopods, and onycholenthus, the meaning of the same, in the vernacular, being the horrible polypus.”

“Why didn’t you stick to wormicular from the jump, and say polly pusses when you meant polly pusses?” growled the old seabear.25

It was Ben’s argument that the various yarns about “uproriusses oxymuriaticusses” were all gammon for landlubbers and the pabulum of a “lily-livered book-worm.” In support of this view Ben alleged he had even seen a savant’s efforts to draw giant squid, a project he declared “ag’in nature” where the squid was concerned, given that the creature was (as any good seaman knew) essentially formless, and thus brooked no scrutiny.

Davis was perhaps exceptional in the self-consciousness with which he articulated, however hyperbolically, a practical seaman’s critique of the whole scientific enterprise. For instance, he institutionalized such a critique in appendix A of Nimrod of the Sea, which depicts New Bedford’s answer to the Royal Society: the back of Kelley’s watchmaker’s shop, where the whaling captains of the city assembled. To that genuinely “learned society” Davis submitted a questionnaire covering a wide range of natural-historical details about the cetaceans—from swimming speed to their habits and distribution—and printed the replies of these grizzled sages. This conjuring of a parallel domain of scientific expertise reached its most elegant formulation in chapter 22, where Davis posed a set of challenging questions about the “embeddedness” of scientific theory in general, questions strikingly like those that have now driven a generation of scholars in the history of science. The topic is the terrifying apparition of a waterspout:

Let us suppose that Newton had seen columns of sea-water, as spirals of glass three feet in diameter, ascending to the clouds, instead of that noted apple falling from a tree. Query: Might not his reflective and ingenious mind have worked out a different theory of gravitation? And would not the schools have been just as well satisfied? Much of science might be different had that gifted Englishman, instead of sitting in an orchard, observed nature in a mast-head watch on some South Sea whaler.26

Where whale taxonomy was concerned, Davis made it clear that he knew that the “learned” in their “books” declared the cetes to be “warm-blooded mammals,” obliged to surface regularly to breathe air. But this did not close the question. He went on to point out that the crew of a thin-planked whaleboat—bobbing on the swell with their oars peaked, awaiting some show from a spouter that had sounded suddenly in the midst of the chase—knew perfectly well that sometimes a whale went down and simply never came back up (at least not within the ample circle inscribed by the horizon): “whales are uneducated, don’t take the papers, and without thought of irregularity, stay down to suit their convenience an hour or a week.”27 Cetology, as much as physics, looked very different when penned from the masthead of a South Sea whaler.

Melville, of course, notoriously made the same point in Moby-Dick.28 Melville could himself claim the practical experience of a whaleman, and the source criticism of Howard P. Vincent and others has made clear how deeply he was steeped in the book-learning on whales through 1850. Chapter 32, “Cetology,” allows Ishmael wide latitude for a wicked and mirthful engagement with the technical anatomy, physiology, and systematics of the cetaceans.29 After giving a long list of those who have written on the natural history of the cetes, Ishmael divides those who had actually seen living whales from the rest, and sides with the practical men—selecting Scoresby, Beale, and Bennett for particular praise—before declaring his intention to “project a draught of a systematization of cetology,” a science, in his view, seriously in need of a whaleman’s callused hand. At the heart of the trouble was the very question at issue in Maurice v. Judd:

The uncertain, unsettled condition of this science of Cetology is in the very vestibule attested by the fact, that in some quarters it still remains a moot point whether a whale be a fish. In his System of Nature, A.D. 1766, Linnæus declares, “I hereby separate the whales from the fish…. On account of their warm bilocular heart, their lungs, their movable eyelids, their hollow ears, penem intrantem feminam mammis lactantem,” and finally, “ex lege naturæ jure meritoque.”30

Just as Davis depicted a jury of old salts reviewing cetological questions, Ishmael announces that he submitted Linnaeus’s classifications “to my friends Simeon Macey and Charley Coffin, of Nantucket, both messmates of mine in a certain voyage, and they united in the opinion that the reasons set forth were altogether insufficient. Charley profanely hinted they were humbug.”

Ishmael therefore resolved the question contrary to the new philosophy, defining the whale in 1851 as “a spouting fish with a horizontal tail,” a description that allowed him to dismiss manatees and dugongs (which don’t spout), but obliged him to include all the porpoises within the “Kingdom of Cetology.”The remainder of the chapter consists of Ishmael’s full sketch of the rank and order of the different whale species, which he organized, library-like, by book size, with the largest as “Folio” whales, descending via “Octavo” specimens, to the “Duodecimos”—an arrangement that amounts to a brilliant satire on the whole project of capturing nature in texts, a parody ad litteram of the very idea of the “Book of Nature.”31

As far as I know, there is no documentary evidence establishing that Melville was familiar with Maurice v. Judd, but it is hard to imagine that he could have missed it: the case was discussed in works he is known to have read (for instance, the whaleman-surgeon Bennett dropped a footnote alluding to the trial in the natural history section of his 1840 Narrative of a Whaling Voyage round the Globe, a volume over which Melville pored); it was the subject of nudge-and-wink asides in the New York newspapers for more than a decade; and Melville was friendly with Dr. John Francis, one of Mitchill’s closest friends.32 But putting aside the minor mystery of Melville’s silence concerning Maurice v. Judd in Moby-Dick (where it would seem to have been irresistible), it is worth noting that whalemen pondering if whales were fish had become a set piece in the emerging genre of the whaling voyage narrative by the late 1840s. For instance, returning to J. Ross Browne’s Etchings of a Whaling Cruise of 1846—a text Melville warmly praised as “always graphically and truthfully sketched” with “true, unreserved descriptions” of whaling life—we discover a memorable instance of this sort of scene. Shortly after the ship takes its first whale, the narrator meets the green hand Yankee-farmboy-turned-reluctant-whaler, “Mack,” looking over the monkey-rail and gazing at the fresh carcass lashed alongside. Striking up a conversation, Browne asks: “Well, Mack, … what’s your opinion of whales?” To which Mack replies, “Why, I was jest a thinkin’ it’s a considerable sort of a fish.” When Browne presses him, asking if he really thinks that this behemoth is a version of the familiar little creatures of the Kennebeck River back home, Mack unfolds his reasoning, revealing that he is aware that there is debate on the matter:

Why, some folks says whales isn’t fish at all. I rayther calculate they are, myself. Whales has fins, so has fish; whales has slick skins, so has fish; whales has tails, so has fish; whales ain’t got scales on ’em, neither has catfish, nor eels, nor tadpoles, nor frogs, nor horse-leeches, I conclude, then whales is fish. Everybody had oughter call ’em so. Nine out of ten doos call ’em fish.33

Despite the interest of picturesque scenes like this one—and more generally, of all the self-consciously belletristic depictions of whalemen’s ideas about nature that appear in the works of Browne, Melville, Davis, and other whaler-authors from mid-century—a satisfying investigation of the whalemen’s natural history must go beyond such artful sources, as it must go beyond the small but influential group of publications by the British whaling surgeons (Beale, Bennett, Dewhurst), who conceived of themselves as hailing from, and writing for, a community of practicing naturalists. In an effort to get less mediated access to the intellectual world of men like Fish and Reeves, I turned to the largest manuscript collection of whaling logbooks and journals in the world, the Research Library at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, which houses approximately 1,500 such volumes, about 800 of which have been extensively hand-indexed by bibliographers working over the last fifty years. Departing from that finding aid, I read my way through fifty journey-logbooks and private whaling diaries, including all of those that dated before 1825 (holdings are sparse in these early years of the American industry; probably 90% of the collection falls between 1835 and 1860), along with a selection of particularly interesting or representative later volumes.34 My aim was to develop a sense of nineteenth-century American whalemen’s attitude toward natural history in general, and in particular to collect evidence about their understanding of the cetaceans.

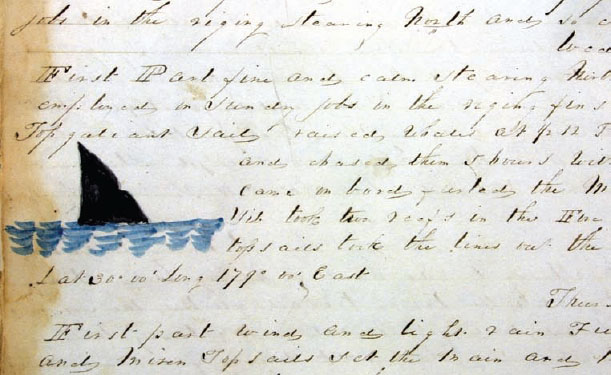

These logs and journals provide a unique window onto the daily life of the masters and mates who made regular entries recording the events of the voyage. While the style is often telegraphic (and there were plenty of keepers who offered minimal narrative and editorial content), culling the richer documents can yield clues to attitudes, training, and tacit knowledge within the whalemen’s tightly caulked world. To give a fair sense of these sources, it should be emphasized that actual ship’s logs were by no means composed as expository texts: on the contrary, sparse notes on weather and location might be buried in a cipher (secrecy mattered to whalemen), and too much gab met reproof as a potential hazard. John Francis Akin, keeper of the log aboard the Virginia, embarking for the Pacific in the 1840s, apologized to his readers in advance for the terse book he planned to make: looking ahead at a thousand days of voyaging and at the thin blank volume he held in his hand, he wrote, “I must only note what is worth recording,” since otherwise “my book will not admit of it.”35 No need for chat in the volume, particularly since Akin was “in hopes to nearly fill it with whales on Japan” (meaning on the “Japan grounds,” the most heavily trafficked whaling region in the western Pacific). And an overzealous anonymous journal keeper in 1850—who expanded, as some sailors did, the narrow conventions of the log into something closer to a commonplace book—learned the hard way that less was sometimes more in shipboard script. His admonitory editorializing on the pessimistic attitude of a number of his shipmates must have fallen under the scrutiny of a superior, since it is interrupted suddenly by a razor-cut lacuna in the page, followed up by a dejected recantation overleaf:

It has been intimated … that such remarks as mine of yesterday should not be placed in so conspicuous a place as a journal. However I contend that the object of keeping a journal should be improvement both intellectual and physical…. I have thought that I would be more definite in keeping my journal in future, but if this my first attempt prove to hurt the feelings of those I would willingly comfort and console, I must again resort to the old skeleton system of weather, and winds, latitude and longitude, gulf weed and grampuses, and let it go at that.36

His “skeleton system” was indeed the norm, but careful and extensive reading in these volumes—recovering the telling aside, sifting for the fortuitous happening that occasioned commentary—can put meat on those bones.

Such research rapidly reveals the limited reliability of Hohman, and of more recent authors who have hazarded comments on the philosophy of nature from the forecastle. Hohman’s suggestion that the average whaleman “knew very little, and cared less, about scientific description and classification” may be correct as far as it goes, but only if one takes as granted a quite narrow view of these activities, since many logbooks reflect an engagement with natural-history collecting, and a preoccupation with the close observation of plants and animals.37 These activities go beyond what Creighton identifies (rather cheerily) as the way “whalemen exulted in their special perspectives on the natural world.”38 Such mid-Victorian transcendentalist apostrophe can be found, but much more interesting for our purposes is a note for the 12th of August, 1822, in the log of the American brig Parnasso, off the coast of Peru, which reports that, permitted ashore briefly, “all hands rambled down towards the west side of the bay, where we picked up shells and other curiosities and returned on board.”39 Other logs report similar collecting, trading, and buying of naturalia by sailors at liberty.40

Where the whales were concerned, close observation went beyond merely a sharp watch from the masthead for the telltale spouts. Yes, whales were frequently characterized by whalemen as capacious tuns of oil—as when a disgruntled New Bedford log-keeper mourned metonymically the loss of a carcass that sank before it could be recovered, writing, “If this is not hard luck I don’t know what is. To kill 140 barrels sperm oil. And then have to lose it and it do no one any good.” And yes, since barrels of oil meant money, whalemen could even use clipped periphrasis when talking about their prey, like Lyman Wing did as his ship the Brunswick plodded northwest from the Horn in high seas, and he fumed in his journal about a “$4,000” sperm that was escorting them on their journey (just out of reach), writing, “the chance is small to get a dollar of it.”41

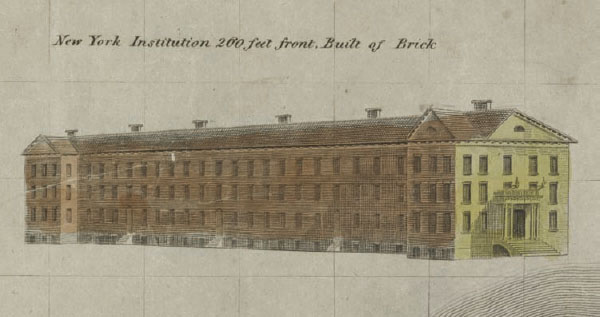

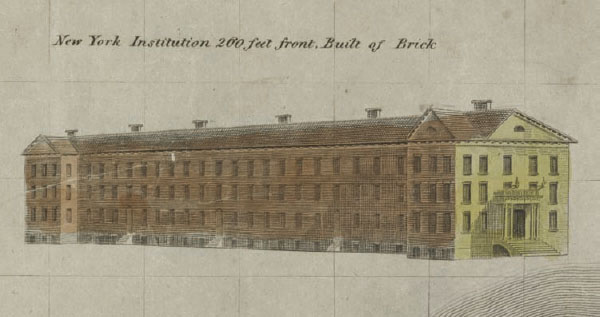

PLATE 1. Where the Whales Were: the city’s palace of learning, the New-York Institution (formerly the “Old Almshouse”). Courtesy of the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, New York Public Library; Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations (a detail from Plate 3, below).

PLATE 2. The Acropolis of New York: the white marble wedding cake of the new City Hall, home of the Mayor’s Court. Courtesy of the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, New York Public Library; Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations (a detail from Plate 3, below).

PLATE 3. The City of New York: David Longworth’s 1817 map of lower Manhattan Island. Courtesy of the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, New York Public Library; Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

PLATE 4. The Civic Heart of Manhattan: City Hall Park, showing the short path linking the philosophers and the politicians; City Hall is number 52, and the New-York Institution is number 55, just a few steps north. Courtesy of the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, New York Public Library; Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations (a detail from Plate 3, above).

PLATE 5. The Universal Man: Dr. Samuel L. Mitchill holding forth on all things (as depicted in a student caricature, circa 1820). Courtesy of the Collection of the New-York Historical Society (PR-145 #73–10, detail).

PLATE 6. A New York Whaleman Draws a Sperm Whale for the Naturalists: Captain Valentine Barnard’s depiction of his preferred quarry (circa 1810). Courtesy of the Collection of the New-York Historical Society (PR-145 #76, detail).

PLATE 7. A New York Whaleman Draws a Whalebone Whale for the Naturalists: Captain Valentine Barnard’s depiction of a right (or perhaps a bowhead) whale (circa 1810). Courtesy of the Collection of the New-York Historical Society (PR-145 #76, detail).

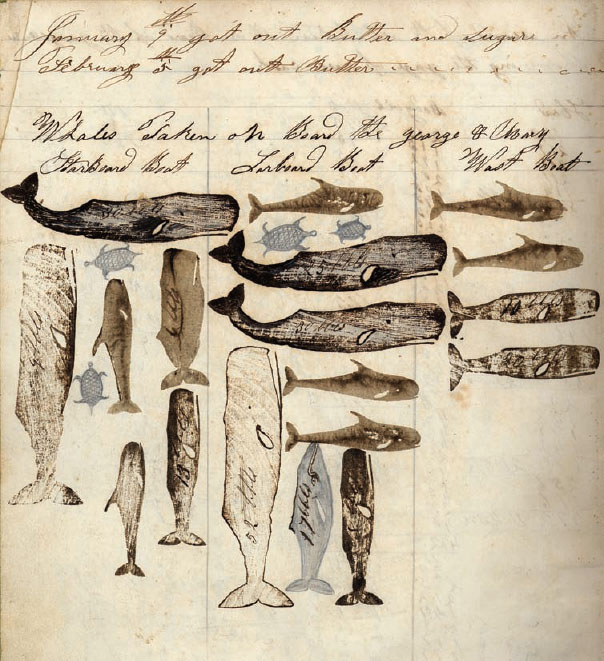

PLATE 8. Keeping Score: the tally of kills by the three boats of the George and Mary, mid-1850s (most of these figures were stamped and then retouched in pen or pencil, but a few—the turtles, the small baleen whale at center bottom—were drawn entirely by hand). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

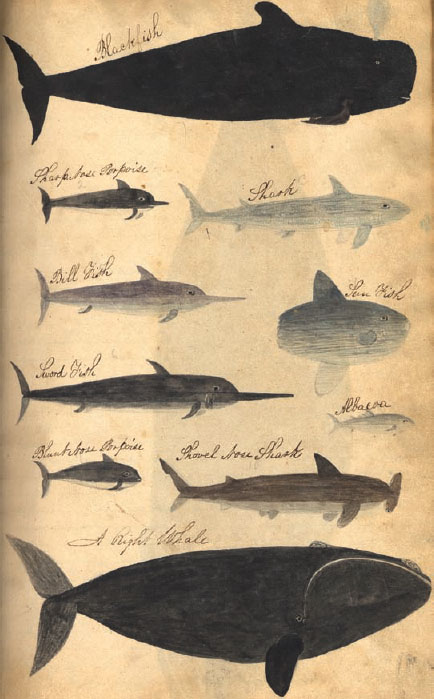

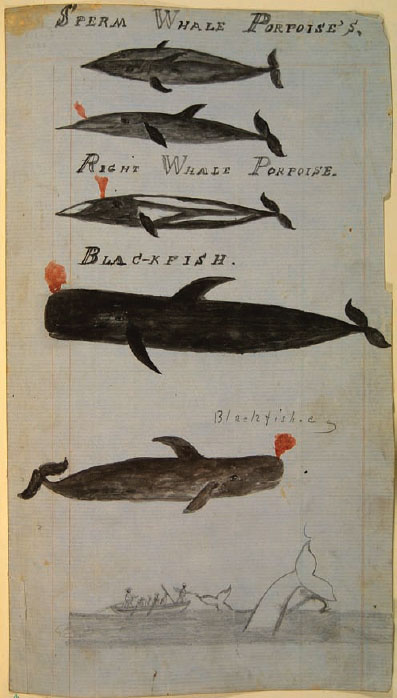

PLATE 9. The Whaleman Takes Stock: Dean C. Wright’s depictions of sea creatures in his commonplace book, 1842. Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

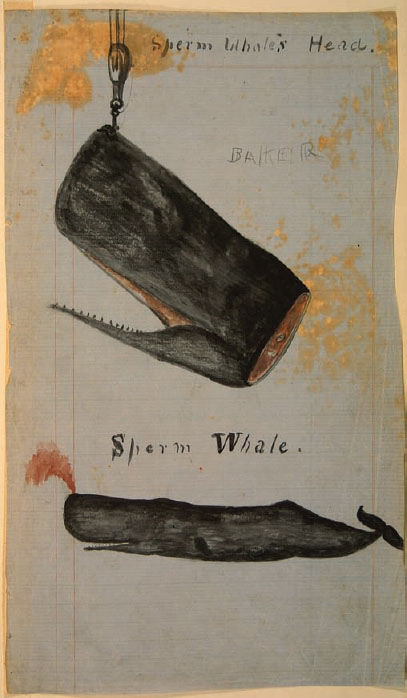

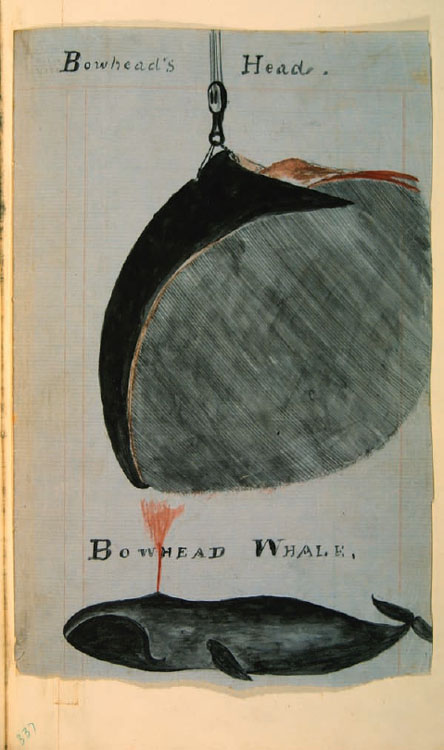

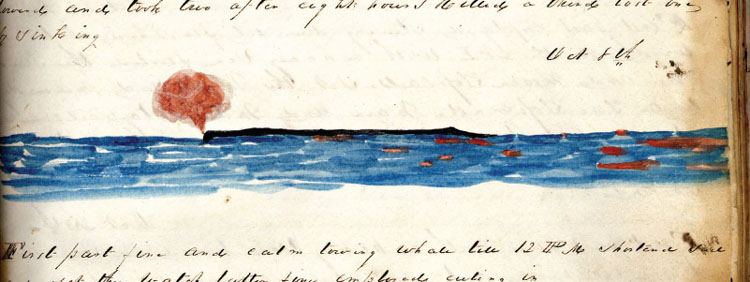

PLATE 10. Spouting Blood: if it came to the surface, it was prey; images tipped in to the journal of Rodolphus W. Dexter, kept aboard the bark Chili (early 1860s). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

PLATE 11. Hoisting the Treasure: a store of valuable spermaceti oil lay inside the “case,” the uppermost part of the head (see Plate 10 for provenance information). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

PLATE 12. Whalebone for the Cutting: the huge upper jaw of a bowhead, being swung aboard the vessel (see Plate 10 for provenance information). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

PLATE 13. Pedagogy on the Deck: an articulated wooden model of the cutting-in pattern, probably used for teaching; a nineteenth-century American artifact. Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

PLATE 14. Between the Lines: the log of the ship Columbia (early 1840s). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

PLATE 15. A Sharp Eye on the Watch: marginal illustration from the Columbia log, depicting a glimpse of a notched dorsal fin. Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

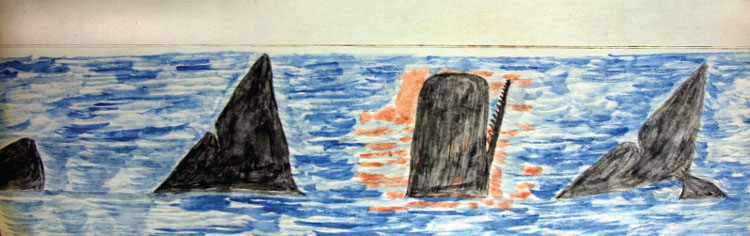

PLATE 16. Sperm Whale at the Surface: the distinctive bushy, forward blow of Physeter macrocephalus (Linnaeus, 1758) has been faithfully depicted (see Plate 14 for provenance information). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

PLATE 17. A Natural History of the Sea Surface: everything in a whaleboat hung on the correct interpretation of the glinting forms that broke, if only for an instant, the surrounding water (see Plate 14 for provenance information). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

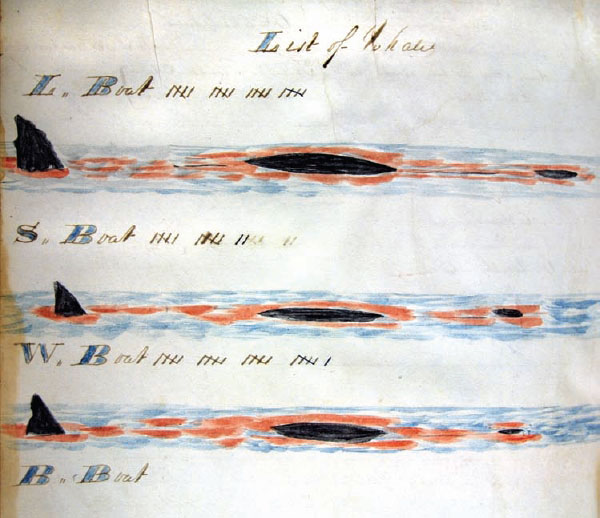

PLATE 18. What Death Looked Like from the Deck: the Columbia’s tally of kills, by boat (early 1840s). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

However, while whalemen made their living reducing whales to money via oil, their interest in the animals was by no means merely reductive. When the Rhine, out of New Bedford, took a humpback cow in the Caribbean on the 28th of January, 1848, the captain permitted the crew to keep the orphaned calf alongside, alive, drawing it into the harbor of the island of St. Ustacia, for an informal public showing to the inhabitants, before letting it go.42 And sailors themselves regularly scrutinized the animals with considerable care and often a great deal of imaginative and original thought. It is perhaps not surprising to read that a learned whaler-naturalist like Scoresby—on the strength of his firsthand experience—assumed the right to depart from the cetological classifications of Lacépède, but it is striking to read the zoological speculations of a common-school-educated able-bodied seaman from Avon, New York, named Dean C. Wright, who hypothesized in his journal in the early 1840s that the “class” of humpback whales might conceivably be some sort of hybrid of the right whale and the sperm, since humpbacks shared features of each.43 Another ordinary whaleman, Joseph Bogart Hersey, took the opportunity of the capture of an anomalous sperm whale on the 21st of February, 1846 (it had visible teeth in the upper jaw, which is uncommon), to record that the species “generally [have] 42 teeth on the lower jaw, whereas this one had 52.”44 He returned to the mouth of his quarry later in the voyage when a strikingly large and old specimen was taken, the majority of whose teeth were rotten. He detailed the behavior of this particular animal, and used the occasion to generalize about this kind of whale:

Note—the whale when first seen was uncommon long between her spoutings, and apparently feeding, for sometimes she would be down an hour, and at others not more than three minutes. The time which generally elapses from a large sperm whale going down (when not startled) and again rising to the surface is from 45 to 70 minutes.45

And Hersey found this very large whale (“120 bbls.,” he noted, again using the whaleman’s standard metric for measuring both whales and whaleships—barrels) sufficiently remarkable that he took the time to draw it into the log, in a schematic diagram with a key, identifying its parts [Figure 4]. This image merits closer attention, since—like other visual material in the logbooks—it is a helpful source for the whaler’s view of the whale, particularly when examined in the context of Hersey’s “philosophical” margin comment on the illustrations in his logbook:

FIGURE 4. A Whaleman Anatomizes His Catch: Joseph Bogart Hersey’s sketch of a massive sperm whale, taken by the brig Phoenix in 1846. Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Note: in my drawings of the different fish in this book I have endeavored to give a correct resemblance of those mentioned in my remarks, and would here remark that there is as much diversity in the form and habits of the inhabitants of the ocean as there is in the shape and customs of the human family.46

This aside takes on special value when it is read after perusing a number of contemporary logbooks, since many of them are illustrated, but by far the majority of their images are tally-stamp depictions of whales used to mark the book’s margin when whales were spotted or taken, or to total the take of the ship’s different boat-crews (who were engaged in an informal competition throughout the voyage). While some log-keepers drew their own tally-figures in pen, pencil, or even gouache [Plate 8], most used inked wooden stamps [Figure 5], in general at least three: one representing a sperm, another a bowhead (or right, which well into the 1850s were often treated as different varieties of the same creature), and a third representing simply flukes, which indicated whales seen, but not captured. The monotony of the cookie-cutter representations is striking, even when the images are labeled (as they nearly always are) by the number of barrels of oil each captured whale afforded (many of the stamps featured a blank vignetted area where this number could be written in).

Read in the context of this representational uniformity, Hersey’s comment on the specificity and individuality of sea creatures is a helpful reminder that, for all the ways that whales were treated as fundamentally fungible entities in the world of whaling (whales, barrels, and dollars were rapidly interconvertible units), there remained an appreciation of the diversity and distinctiveness of the fauna of the sea. The Reverend Henry T. Cheever, who took passage back from mission work in the Pacific via whaleship in the 1840s, and wrote a book about the experience entitled The Whale and His Captors (1849), reported that “practiced whalemen” enumerated for him “twelve or fourteen different species of this great sea monster,” and indeed a number of logbooks contain “key” pages where numerous cetaceans and other sea creatures are depicted and named, images that almost certainly reflect familiarity with similar images in printed works of natural history [Plates 9, 10; Figure 6] (though the whalemen added their own touches, for instance depicting all the whales spouting blood, as in Plate 10). While relatively few manuscripts reflect so many distinctions as Cheever reported, there are moments when the close knowledge of the whaler speaks through the relatively rigid conventions of the logbook genre. For instance, when Captain James Townsend of the ship Louisa came across a dead fin whale floating belly-up in the Atlantic on the 12th of May, 1829, he used his stamp for a right whale in the margin (apparently having no fin whale stamp, since these strong, fast swimmers were not hunted, and were thus more or less irrelevant to the log), but he then meticulously penned in a minute fin on the mid-back of the image, to bring his stamped depiction into conformity with nature and nomenclature.

Returning to Hersey’s diagram of the whale [Figure 4] and the key that he wrote to accompany it, several features deserve comment. Most significantly, this image must be recognized as a manuscript instance of a kind of diagram that became an increasingly common feature of published texts on whaling over the course of the nineteenth century: the cutting-in pattern. Because the sperm-whale fishery was a pelagic enterprise—an industry that not only took whales at sea, but also processed them there, melting down the blubber in the brick “tryworks” positioned amidships—a central aspect of the craft was the high-seas butchery of the very large carcasses. This process, described in any work on nineteenth-century whaling, involved lashing the dead whale alongside the ship and then, using tackle fixed in the rigging, winching off strips of the whale’s external “blanket” or blubber layer. Whalemen, either placed on the whale itself (and walking on it, like a lumberjack on a log as it rotated in the water), or leaning out over it from platforms suspended over the ship’s side, used sharp spades to cut the edges of the strip as the winch peeled it from the body. When the strip was as long as the winch could manage (i.e., the leading edge had been drawn up to block itself—perhaps twenty feet above the water) the men with the spades fixed a new hook at the base of the strip and cut the completed length free, allowing it to be swung on deck for further trimming and mincing en route to the kettles. A fresh strip could then be begun, continuing along from where the old had been cut loose, and spiraling around the animal continuously, exactly like an artfully peeled orange. This process, with a number of attendant operations for processing the head (which contained a large amount of the most valuable spermaceti oil in an interior reservoir, and therefore had to be handled differently), and the jaw (usually severed and lifted aboard so the teeth could be removed), was known as the “cutting-in.” It differed in several respects for the major commercial species, since, for instance, bowheads and right whales did not have a reservoir of spermaceti in their heads, though they did have the valuable “whalebone” or baleen plates in their mouths, which necessitated different operations [Plates 11 (for sperm) and 12 (for bowhead)].

FIGURE 5. Tally Stamps of the Sarah: at least six different stamps are used here, and one of the sperm stamps actually shows the cutting lines for the separation of the different parts of the head; the stamp in the upper left corner has been annotated in pen to indicate a pregnant animal (circa 1870). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

FIGURE 6. Species of Whales: as depicted by the whaleman John F. Martin, aboard the Lucy Ann (1843). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

A close look at Hersey’s image with the details of this process in mind reveals that his sketch is more than a drawing of a particular whale. It is in fact a cutting-in diagram, a schematic for this sort of large-scale dismemberment. Below the eye, for instance, at the point labeled with the number 5, the artist has drawn a hook set in a hole. The key reads: “No. 5. Is what is called the blanket piece with the blubber hook in the boarding hole—this is where they generally first hook onto the whale.” In other words, the first strip of the peeling process (the strips were known as “blanket pieces”) began at the hook as shown, and proceeded up as the yanking tackle turned the animal in the water, the sides of the strip following the parallel lines drawn on the body, circumscribing the eye and running up to the top of the head. Other lines on the diagram indicate the incisions to be made in the careful process of separating the “case” of the head (along the straight diagonal line between regions 1 and 2—Hersey’s numeral “2” is that squiggle beside the round ink drip) from the “junk” below. Here, while the basic cuts were standard, different approaches could be used depending on the size of the whale, the conditions of the water, and the habits of the captain and crew. One possibility was to sever the head entirely from the body, and then bring the whole head aboard (if it was small enough—as shown in Plate 11) so as to ensure that none of the best “head matter” would be lost to the waves; another was to use block and tackle to suspend the severed head—bucket-like—over the side, nose-down in the water. From this position the case could be “bailed” by a man standing atop the head and driving a bucket down into the soft and oil-rich tissue.

Whalemen took the niceties of these operations very seriously, so much so that they approached the different options as exacting empiricists: Master John Swift, of the Samuel and Thomas out of Provincetown, arranged for a trial of two techniques when his vessel took two similarly sized sperms on 25 June 1847. The log recorded the effort: “cut in the first one by way of experiment leaving the scalp on the body—the other taking the head in whole. The first method proved the most expeditious, though not quite so saving.”47 This meant that each had its virtue: if whales were plentiful in the area, speed mattered more than economy, but rough waters could make the hasty method still more wasteful, and therefore costly.

The earliest known printed cutting-in diagram—much copied during the nineteenth century—appeared in 1798, in Captain James Colnett’s A Voyage to the South Atlantic and round Cape Horn. Colnett’s voyage, in the English ship Rattler (he was a Royal Navy officer), was undertaken for the purpose of “extending the spermaceti whale fisheries” into the Pacific, and it received some Crown support. Although Colnett himself was neither a whaler nor a naturalist, he applied himself diligently to his task of reconnaissance, and went so far as to see to it that a small (15-foot) cub sperm whale taken in late August, 1793, off the western coast of Mexico was hoisted on deck in its entirety. He drew the animal, and inscribed on his figure the cutting lines used by the whalemen to butcher it (the Rattler had been outfitted by the English whaling firm of Enderby and Sons, and thus had knowledgeable whalemen aboard) [Figure 7]. Colnett also included a detailed key describing the process [Figure 8].

In his useful article “The Historical Evolution of the Cutting-In Pattern, 1798–1867,” Michael Dyer has traced the sequence of borrowings and redrawings of Colnett’s image, in an effort to establish a stemma for this iconic figure. Close analysis of a dozen printed exemplars has enabled Dyer to distinguish those changes in the diagrams that can be interpreted as evidence for actual historical developments in the cutting-in process from those alterations most probably owed to sloppy print-piracy [Figures 9–13; Plate 13].48 Without rehearsing his argument, it suffices here to note that these representations clearly indicate an extensive and minutely detailed anatomical expertise that was the exclusive provenance of the whalemen. It bore little (indeed, perhaps no) relation to the anatomy of the anatomists, but rather functioned as an autonomous domain of natural knowledge. It might even be suggested that something like a “physiology” attended this vernacular anatomy, if of a very particular sort: again observing Hersey’s drawing [Figure 4], and focusing on the shaft fixed in the animal’s side (labeled “No. 11” in the image), we find that Hersey has annotated this detail, and identified it less as a depiction of the whaleman’s fatal tool than as a pointer, a blubberhunter’s manicule that fingers a relevant anatomical/physiological aspect of the sperm whale.

FIGURE 7. The Cutting-In Diagram: Captain Colnett shows how to peel a whale (published in 1798). Courtesy of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

FIGURE 8. Follow the Instructions: Colnett’s description of the cutting-in process. Courtesy of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

No. 11. A lance the point of which has entered the place commonly called the life of the whale, or where a wound would prove mortal.

In this sense the “life” of a whale was a point on its body: a point—the point—of greatest relevance to the whaler.49 Touching the “life” of the whale was the whaler’s culminating aim. As if in oblique acknowledgment of this fact, Captain Colnett noted that immediately after he had drawn his specimen, “its heart was cooked in a sea-pye, and afforded an excellent meal.”

FIGURE 9. Thomas Beale’s Cutting-In Diagram: along with a small head-on schematic view of a sperm whale, showing what Melville would later call “The Battering-Ram” (image published in 1835). Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

FIGURE 10. Robert Hamilton Copied from Colnett: but made the whalemen’s anatomy available to a large readership of landlubbers, via publication in Jardine’s Naturalist’s Library series (1837). Courtesy of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

But if cutting-in images are valuable sources in the whalemen’s natural history—in that they provide clear documentation of what whalers knew about the anatomy and physiology of their prey, and indeed evoke a broad domain of tacit knowledge about the body and vitality of these animals—it must nevertheless be emphasized that this was, in a literal sense, a “superficial” anatomy. It is surprising, for instance, to read Captain Scoresby (whose hands had rifled the carcasses of more than one thousand bowheads in the Arctic seas) cite a bookish authority for the number of ribs the animal possessed.50 How was it that Scoresby did not know this himself, from his own extensive experience? The answer, of course, is that even a committed naturalist-whaleman like Scoresby had never, when engaged in business, taken the opportunity of the hunt to perform an exhaustive dissection on these animals as they floated beside his ship. In fact, given that the fat-stripped carcass not infrequently went directly to the bottom (when no longer buoyed by its insulating blubber layer), such an undertaking might have been impossible—putting aside how unpleasant it would have been to try, standing on a cadaverous raft waist-deep in a slurry of polar water and viscera. While Scoresby had once or twice seen to it that a stomach was opened (to observe what the animals had been eating), he was forced, for all his intimacy with the creature, to rely on the published work of museum naturalists for the deep internal anatomy of the Balaena mysticetus, particularly the skeleton. Captain Fish, on the stand in Maurice v. Judd, found himself obliged to make the same confession: while he knew sperm whales up close, and had cut into many dozens of them, and had, with his crews, pawed through their intestines (as whalemen regularly did in pursuit of lumps of precious ambergris), he had to admit that the bones lying under their meat were beyond his ken; when Sampson pressed him on the internal anatomy of the whale’s fin, Fish acknowledged that “I have never dissected any of them,” and Sampson shot back, “I can very well perceive it Mr. Fish.”51

FIGURE 11. Francis Allyn Olmsted’s Cutting-In Diagram: showing the block and tackle positioned to winch the first strip (1841). Courtesy of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

FIGURE 12. Chase and Heaton Copied from Beale: and gave their whale a particularly fierce-looking “eyebrow”; one suspects that whalemen would have snickered (1861). Courtesy of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

So cutting-in, despite all the gargantuan surgery it entailed, was not “dissection.”52 At the same time, the whaleman’s “superficial anatomy” must be acknowledged (perhaps paradoxically) as a profound knowledge of the superficies of the animal. The “blanket” was what mattered to whalers, and their cetological nomenclature reflected their preoccupation with the three-to-fifteen-inch-thick blubber envelope that was their livelihood. For instance, whalers recognized the “dry-skin whale” as a type of cete, a designation that passed unnoticed among taxonomists: a “dry-skin” whale was a whale of any species that, for one reason or another, had little or no fat upon its body. Such a characteristic was, among whalers, salient enough to eclipse the morphological differentia of the schools. Similarly, whalemen had several idiosyncratic names for specific regions of a whale’s external anatomy, and yet this terminology did not denominate any visible “part” of the animal that might be spotted by a passive observer, but rather indicated the way whalers perceived the quality of the skin at those points under particular conditions: Dean C. Wright pointed out that in sperm whales “Both the case and junk are guarded [by] a substance called headskin, which is very hard, and is almost impenetrable to a harpoon, and thus their head is rendered very formidable in their defence”; those who pursued right and bowhead whales were accustomed to talk of “slack blubber,” an impenetrable area that the whales could move about their bodies at will, by twisting themselves to thicken their external tissue.53 Tellingly, the term “black-skin” could be used among whalers as a synecdoche for the whale as a whole.

FIGURE 13. A Superficial Anatomy: Charles M. Scammon, an American West Coast whaleman-naturalist, offered the most detailed cutting-in diagrams of the nineteenth century, depicting both a sperm and a whalebone whale (1874). Courtesy of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

In these details, in the extensive vocabulary and metrics applied to the blanket, and in the evolving craft of the cutting-in process, we see the contours of the whaleman’s “superficial” anatomy, an anatomy that was superficial only in the narrowly literal sense: there was nothing “shallow” about it (excepting the depth into the body it reached), since, in its domain, it was in every respect more detailed and closely observed than anything zoologist-savants had to offer. At the same time, it is worth noting that the contrast of this whaler-anatomy with the preoccupations of the new comparative anatomy—given the latter’s increasing attention to deep inner structure—could not have been more complete.54

The notion that the whalemen possessed a superficial natural history felicitously evokes another significant dimension of whalers’ knowledge of nature. Spending time with whaling logs, one is promptly struck by the many sea-surface views they offer—depictions of the water, of the “face of the deep,” abound, sketched between lines of text or brushed into narrow margins. What takes a while to appreciate is the way that these images constitute a veritable natural history of the surface of the ocean. Unlike cabinet students of nature, who received their sea specimens in jars or crates, or perhaps encountered their large cetaceans distended on the strand, the whaleman’s visual contact with sea fauna—the different species of shark, turtle, dolphin, whale, and fish that were his continuous preoccupation for hundreds and often thousands of days—was most often a glimpse at the juncture of water and air. These men saw what surfaced: a fin, a tail, a nose, a spout. It is little wonder then that their journals represent the “fish out of water”—the image of a sea creature lying on the page—much less often than they depict the sightings relevant to their working world: the fin, blow, or splash that breached the undulating plane separating sailors from the deep. The keeper of the log of the Columbia, for instance, painted dozens of sea creatures, consistently limiting himself to the bit of black that tipped out above the waves [Plates 14–17]; his sketches amount to a field guide for the naturalist in the crow’s nest, an identification key to the whales one saw as one sailed and sought them where they lived. Indeed, so taken was this log-keeper with this superficial view of the sea and its inhabitants, that even when he tallied the takings of the ship’s four boats, he depicted representative dead whales, lying in water, breaking the surface only in three places, three distinctive darts of black-skin that were the “footprint” of the whale in the world of daylight [Plate 18]. Since “reading” the surface of the sea was the primary means by which whalemen found, identified, and tracked whales, it is perhaps no surprise to discover such care lavished on this form of silhouetted and glancing natural history. As Browne put it, concisely, “it is the primary object in whaling to see whales when they appear above the surface of the water, so it is the chief qualification of a good whaleman to understand thoroughly the different species of whales, and how to distinguish them.”55 In an effort to show what this meant, he included a practicum of whaler-knowledge: a depiction of the blinkered view of the three most familiar species [Figure 14]. Blinkered, to be sure, but by no means blind; if anything, this was a vision enormously refined and focused in its calculus of the flashing and the fragmentary. There was little patience for whalemen who failed this test: lowering the boats for finbacks, say, mistaking them for a catchable species, wasted everyone’s time and energy, yet it was certainly known to happen. The anonymous log-keeper of the Cowper, out of New Bedford for sperm whales in the summer of 1846, showed little mercy for a crewman inept in this art: “saw whales lowered and the second mate could not tell which end the whales [sic] head was on, so ends.”56 A mid-nineteenth-century French naturalist who spent some time among whalemen was flabbergasted by their abilities when it came to reading the splash and spray:

The whaleman knows how to distinguish the true whales [right whales] from every other species of cetacean by the form and by the color of whatever appears above the surface of the sea when they are swimming, as well as from their manner of rising and diving; and at a greater distance by the shape of the vapor from their exhalations, which from a certain distance resemble (indeed, could be taken for) jets of water. Even in the dark of night, he can distinguish them from the mere sound of their breath, which can sometimes be discerned more than a kilometer off.57

For all the significance of these two kinds of “superficial” natural history (the surface of the whales and the surface of the sea), whalers were possessed of a penetrating intimacy with their prey as well. Colnett’s hearty “sea-pye” reminds us of an important aspect of the whaleman’s “communion” with the animals he hunted: more or less perpetually hungry (and often actually undernourished), on account of their monotonous diet of poor salt meat and hard biscuit, whalers seldom spurned the “sea beef” afforded by the cetes.58 Porpoises were a perpetual favorite (harpooned from the bowsprits), and the liver and lean muscle were eaten with relish, often in floured dumplings known as “porpoise balls”; a similar dish could be concocted out of the brain of sperm whales, kneaded into “fritters.”59 The thin edge of the lip of the right whale, allowed to simmer overnight in the hot oil of the trying kettles, “becomes the consistence of a jelly, which, when eaten with salt, pepper, and vinegar, closely resembles pigs’ feet.”60 Blubber could be pickled, and portions of the tail could be parboiled and fried, and Scoresby acknowledged that “the flesh of young whales, I know from experience, is by no means indifferent food.”61 It is a telling clue to the whalemen’s sense of how the “spouting fish” fell taxonomically with respect to the quadrupeds that the term “cow-fish” was used to designate a host of the smaller odontocetes, and while one might readily talk of “whale bacon,” fish bacon was inconceivable.62 Against this background Melville’s highly wrought depiction of “Stubb’s Supper” (chapter 64 of Moby-Dick), with its evocation of the man-shark devouring his prey as a steak while the shark-sharks work cannibalistically on the carcass below him, must be understood as an allegorical rendering of a familiar shipboard ritual.

FIGURE 14. Reading the Mist: J. Ross Browne’s key to species identification, according to pattern of blow (1846). Courtesy of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

Such rites of blooding and consumption represent more than just appetite. They also elaborate the charged intimacy of the huntsman: it was the task of skilled whalers to develop an inwardness with the ways of the whale, to grow familiar with the sensory range, sight lines, foibles, and wiles of their prey, and to achieve reliable intuitions about the beings they pursued. “It smells rather whaley,” noted the log-keeper of the Columbia, cruising the line on the 11th of January, 1844, attesting to the hunter’s keen sixth sense as he took in the water conditions, the birds and flotsam and glinting surface activity of the equatorial Pacific; he added, as a note to himself and the crew, “look sharp boys.”63 Looking sharp for whales meant honing one’s own horizon-eye vigilance, for certain, but it also meant paying very close attention to the perspective of the prey itself. Illustrating his account of the chase, William Davis included an image of a sperm whale’s visual field, and showed how a boat might approach from the rear without “gallying” (spooking) the catch [Figure 15]. Whaling lore included intricate ideas about the whale’s sensory universe, some of which may have functioned as mnemonic devices or rules of thumb for the assault. For instance, many American whalers held that sperm whales were sensitive to the passage of a pursuing boat through their “glip,” or the smooth streak of water in their immediate swimming wake. It is not clear how this strange idea arose, redolent as it is of sympathetic magic, but application of the principle would have resulted in a shallow angle of approach from the rear—an excellent way to avoid both the animal’s visual field, and its flukes, which could be used for a fearsome defense.64

FIGURE 15. The Line of Attack: William M. Davis considers the sperm whale’s visual field (1874). Courtesy of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

The different means by which the various species reacted to attack, and their respective vulnerabilities, these were the most essential elements of whalemen’s whale-knowledge, and they carried over into the kind of anthropomorphic preoccupations not uncommon among those who make their livelihoods outsmarting wild animals. Dean C. Wright, for instance, who served for four years as a harpooneer, and thus went eye to eye with hundreds of whales in three oceans, confided to his journal that sperm whales were distinctive not only in profile, but also in their intelligence:

a sperm whale is a species alone, no other kind seeming to be of his form or nature, for he is not only a different shape from all other whales and worth more than any others, but the sailors say that “they know a d—n sight more than the others”; and I think there is some truth in the expression.65

Moreover it was recognized that some individual whales were “smarter” than others, a theme difficult to avoid after 1821, when a suite of articles and pamphlets recounted to chilled readers the tragic tale of the wreck of the whaleship Essex, sunk by a bull sperm whale on the equator in the Pacific in November of 1820. Whales crunching twenty-five-foot open whaling dinghies was a standard hazard of the chase; a whale using its head to ram to destruction a fully rigged ship—hulking with its multiple decks and masts and armed with a hull designed to stave off Cape Horn tempests—was a sensation, and countless readers devoured the survivor’s tales (which included lurid details of murder and cannibalism), and shivered to read the eyewitness accounts of the injured animal’s first blow to the bow, and then its retreat, pause, and second fatal charge—fatal, that is, to the Essex. Such a story, so widely hailed, gave immediate resonance to whalemen’s stories about specific whales that were “wild,” or, as the terminology had it, “ugly.”66

The social behaviors of the animals mattered as much as their individual wiles, particularly as such habits might be exploited in the hunt. Hersey, for instance, mentioned in his log that the boats of the Phoenix, coming upon a group of sperm whales that included several females with calves, tried the whaleman’s familiar trick of striking a cow whale and just hanging on, in the hopes that the other females in the pod would come to her aid (or “gam” with her, as sailors put it)—creating excellent opportunities for multiple catches.67 Sometimes sticking a calf worked even better, and the practice—used in the pursuit of sperm, right, and bowhead (and later in the century for gray whales as well)—struck many observers (and even some whalemen) as unfortunately cruel, particularly when animals were thus betrayed by what looked like “maternal affection.”68 Dean Wright thought too much was made of this tangibly un-fishy characteristic of his prey, and he noted that “The general idea of the great affection which the cow has for her calf is rather exaggerated if my experience be correct, for I have frequently seen the cow leave her calf; but in some cases she shows great regard for her young and will rather stay and be killed than leave it.”69

Stories of both flight and fight could serve to “humanize” these creatures, so alien to most non-whalers. A number of whalemen who commented on whales for land-bound readers went out of their way to emphasize that, mothers aside, whales were generally “timid” animals, easily frightened and quick to take flight, and as the global whaling industry climbed to its apogee at mid-century (and as the depletion, indeed the potential extermination, of great whales became a topic of commercial and bien-pensant concern), several authors hazarded whale’s-eye views of the world, often tinged with maudlin sentimentality: bookshelves in 1849 held a volume that claimed to be nothing less than “The Whale’s Biography,” and a year later The Friend of Honolulu—a newspaper published by the Oahu Bethel Church, and perhaps the most widely circulated periodical among Pacific whalemen—printed a plaintive “letter to the editor” from “Polar Whale” (address: “Anadir Sea, North Pacific”) in which this spokesman for an “Old Greenland family” lamented the fate of his many confreres, and pleaded for “friends and allies” to “arise and revenge our wrongs” lest ignominious extinction descend upon his “race.”70

Such bathetic treatments undermined—or perhaps simply remained in tension with—the characterizations of whales as “monstrous” beings, depictions that retained currency in much nineteenth-century popular published writing on the cetes, and that had a place in the sea chanteys and doggerel of the whaleship as well. It took a minister like Cheever to truck out Milton (who notoriously likened Satan, floating on the burning lake of hell, to the vast bulk of the Leviathan), but New England whalemen throughout the century joined in choruses of “A Whaling Song,” with its invocation of the “monsters of the deep,” “the monstrous fish” with her “monstrous body,” who was the whaler’s “deathful prey.”71 And whalemen did not shirk a proper Miltonian diabolism of their own: Cheever might go so far as to assert that the “moving sea-god” was nothing less than the embodiment of Mammon himself (particularly since seamen’s relentless pursuit of blubber-lucre generally meant that there were, as the saying had it, “no Sundays off-sounding,” i.e., no Sabbath at sea), yet whalemen too hypothesized that “wild and ugly” whales had the actual devil in them.72 Moreover, whalers (and not just Melville) sometimes took up a gallows humor, and embraced the diabolism of their trade as a whole.73 Certainly there were pious whalemen, like Clothier Pierce, who scribbled in their logs ejacular supplications for divine aid (“Forgive me Heavenly Parent, my past Sins and transgressions & Oh, Lord Bless us soon to get One Whale is my Earnest Prayer”), and there were those who moralized the whaleman’s role as a godly alchemist who converted “creatures of darkness” into the sources of domestic light, but William Davis took a wry look at such energies: he suggested that a whaleman might return home, forever the most prodigal of sons, and announce simply, “Father, I have whaled,” an admission that was the résumé of all sin.74 This vision of the whaleship as an impious saturnalia is perhaps best captured by the lyrics to “Jack and the Whale,” the American whaleman’s scurrilous inversion of the tale of Jonah, which was passed along and altered by oral transmission through the nineteenth century: The blubber-hunter Jack, confronting “the whale that swallowed Jonah,” finds himself similarly ingested, but in defiance lights up his pipe and puffs away, making the beast of divine retribution sick to its stomach (a very different sort of “harrowing of hell”). When the whale tries to spit him up, Jack refuses to go, and, clinging in the monster’s mouth, proceeds to kill the whale with his bare hands, tossing it ashore and cashing in comfortably on the value of the oil.75 So much for divine retribution.

Somewhere in the mixture of devilish whales and apostate whalers, a subtle kinship of outlaws could take shape. The log-keeper aboard a New Bedford ship recorded a battle royale against a large sperm on the 16th of April, 1849, with a tip of his cap:

saw whales and lowered and struck one … he was a real devel, after being fast to him for about four hours he went off by taking the line … there was attached to him 12 irons 4 lances two lines and a half, 2 drugs [wooden sea anchors used to slow up a fleeing whale], one spade, and he capsized the starboard boat. success to him I say.76

Such an aside points to the ways that the whaleman’s familiarity with his quarry might limn a sympathetic union stranger and more profound than the aromatic special pleading of the mission press with its saccharine pleas for the persecuted “Polar Whale.” A hunter might sing out—as whalemen did—“Death to the living, long life to the killers” as a way to speed the oar in pursuit of “wood on black-skin” (running the boat “aground” on the fleeing whale’s back, to give the harpooneer pointblank range), but the same phrase also functioned to help the killers keep a certain kind of distance.77 After all, both Cheever and J. Ross Browne, for instance, cited whalers expressing misgivings about the sufferings of their catch, and while Browne may well have given himself fictional license when he made those misgivings the theme of a passage that recounts the whaleman’s ultimate nightmare, this does not detract from the creepy power of “Barzy’s dream” (about the “un-Christian business” of whaling): “I dreamp,” announces Browne’s protagonist to his messmates, roused from their berths by his cries, “I dreamp I WAS A WHALE.” And Barzy proceeds to narrate his experience of “being” the object of the ship’s relentless pursuit, detailing his bloody capture, and his terrifying awareness of each stage of his rendering—as he is skinned, dismembered, and, finally, melted, cognizant of his own unmaking all the way through the stinking process. Barzy summed up the lesson thus: “Whales has feelings as well as any body. They don’t like to be stuck in the gizzards, and hauled alongside, and cut in, and tried out in them ’ere boilers no more than I do.”78 His fellow whalers declare this unsettling reverie “the climax of all the dreams we had ever heard,” but as men sealed in a predatory pact—and many of them hailing from farming lives in which slaying large animals was a familiar autumn labor—they shake off its uneasy implications.79

Even if we dismiss Browne’s hallucinatory tale as a confection, it cannot be denied that whales and other sea creatures had a way of worming themselves into the minds of the men who thought of little else for years on end. William W. Taylor, second mate aboard the South Carolina out of Dartmouth, edging along the east coast of Greenland in January of 1837, recorded an oblique account of a “remarkable dream” about walruses and other beasts of the polar waters. And as the hardscrabble sailor Daniel Kimball Ritchie—recently sprung from jail in the Sandwich Islands—found his slow way home on the Israel, meandering across the widest part of the Pacific in pursuit of sperms, he realized the beasts had come to occupy the whole of his mental universe: “Cruising for sperm whales but in vain…. I am in day looking for them & in night thinking of them.”80

It is also the case that the language of whalemen contained a cluster of terms whose slippery usage betrays that something more than a stout manila line bound whalers to their prey, terms that suggest sometimes the resurrection of a dead metaphor can bring a buried kinship to light. This went beyond the curious convergence of slang like the noun-and-verb “gam,” which applied both to gregarious whales in their groupings and gregarious whaleships drawn up at sea for sociability. And perhaps not too much should be made of the fact that whales and whaleships shared the common denominator of the cooper (since both were forever measured, as discussed above, in barrels). But a close reading of the words that whalers left reveals elaborate and suggestive puns that lurked in the whalemen’s repertoire—for instance, the use of the phrase “her whaleship” (by way of “her worship”) to name not a vessel but a cete, as in the pregnant pre-Freudian chantey “How to Catch a Whale”:

On land Poor Jack secured his prize,

He stuck a knife in her belly,

Which made her whaleship roll her eyes,

And look like a lump of jelly … 81

Inside the body of his catch Jack finds a fleet of actual whaleships, which sail stately out of her corpse: his prize was thus carrying whaleships in her hold just as whaleships carried their whales, stowed down in their casket-kegs. Such phantasmagoric folklore traditions leave little doubt that “whale-men” were, we might say, acutely unconscious that theirs was a compound name. Jeremiah N. Reynolds, coming upon an exemplary American whaleman on a New York vessel in the Pacific in the early 1830s, gave clear voice to these zoomorphic whisperings:

Indeed, so completely were all his propensities, thoughts, and feelings, identified with his occupation; so intimately did he seem acquainted with the habits and instincts of the objects of his pursuit, and so little conversant with the ordinary affairs of life; that one felt less inclined to class him in the genus homo, than as a sort of intermediate something between man and the cetaceous tribe.82

For confirmation that there was something, well, “amphibious” in the progressive convergence of the dedicated whaleman and his prey, we need look no further than the durable nautical slang for a whaler-seaman, who might be known to chums as a fish.83