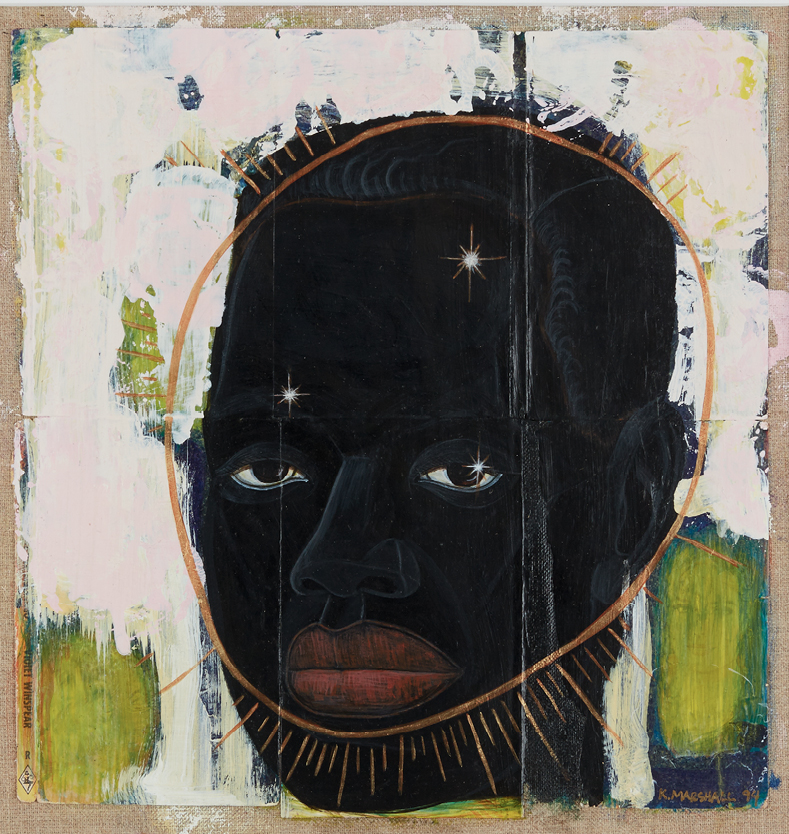

Kerry James Marshall

Lost Boys: AKA Black Johnny, 1995

Acrylic and collage on canvas, 24¾ x 24¾ inches

© Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

THE FLESH GIVES EMPATHY

JASON PARHAM

It begins with flesh. With meat and muscle. With a matrix of tissue. It begins with the body—textured and text. The body as vernacular. The body as song. It begins, simply, with Black skin.

In 1986, years before I would come to understand the world as uninviting to the people I loved, and that in some way it had always been like this and might always be, Professor Kellie Jones and the artist David Hammons convened at Brown University. “I was trying to figure out why Black people were called spades, as opposed to clubs,” Hammons told Jones. “Because I remember being called a spade once, and didn’t know what it meant; nigger I knew but spade I still don’t. So I took the shape and started painting it.”1

Thirty years after that, literary scholar Hortense Spillers insists upon a radical act of sight: “The flesh gives empathy.”2

Empathy is what we seek. Empathy is our end point.

Under the heaviness of each new day, where we labored to make our dreams into destiny, our skin was cast in shadow and soot. Coon. Crow. Spook. Darkie. Tar baby. Buck. Ape. Mammy. Porch monkey. Pickaninny. Sambo. Slave. Jungle bunny. Jiggaboo. Nigger. Nigger. Nigger.

Kerry James Marshall (b. 1955) wrestled with these experiences; they were jagged and rusty realities he knew with a brutal, devastating intimacy. In an interview with Callaloo in 1998, on the occasion of his multiyear series Lost Boys, Marshall explained that such experiences “sat heavy on my mind,” elaborating on how “all of those things kind of came together with the fact that my own brother now seemed to be one of those lost” (Marshall’s youngest brother was incarcerated for seven years).3 But these boys did not remain astray for long. Across nine portraits, Marshall returns them to us, with velvet-dark skin and eyes made of pearl.

In the center of small vertical frames, their faces linger solemnly, unsentimentally, mischievously. They quake with color—palatial blues, sumptuous yellows, deep greens, reds the temperature of cinnamon and worn brick. In one standout from the series, titled Lost Boys: Dark and Handsome, a gold halo encircles an emphatic Black face. The nameless figure’s eyes dart forward, looking just beyond the viewer, and his profile is aglow with small bursts of light—in Marshall’s formulation, these dots represent the “luster, the shine, the sparkle.”4 The Alabama-born painter extends a corrective and a challenge to the White mainstream, a benediction to his kin: “The notion that just as Blackness is apparent, their beauty can also be apparent in their Blackness.”5 Lost Black boys. Troubled Black boys. Dreaming Black boys. Beautiful Black boys.

Kerry James Marshall

Lost Boys: AKA Black Johnny, 1995

Acrylic and collage on canvas, 24¾ x 24¾ inches

© Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Kerry James Marshall

Dark and Handsome, 1994

Oil on paper on canvas, 17½ x 16¼ inches (image size), 22 x 21 inches (framed)

© Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

In that space, in that vast topography, a question arises: Who is this boy? The answer you seek lies in the look and the texture of the figure—what has become a singularly distinctive style employed throughout Marshall’s career-long project (craftwise, he uses carbon black, ivory black, and mars black, and rotates in four colors to add chromatic gravity to the matter-of-fact complexion of his subjects). It is identity in the absolute—lush, expansive, definite. Black as tar and bright as gold. As a result, Dark and Handsome becomes a study in distance and depth. Who is this boy? Marshall answers. Beauty sought can be a bridge. Let us cross it together. Let us close the distance between our very selves.

I would like to assemble a new roadmap.

Black skin as nonapology. Black skin as hammer. Black skin as symphony. Black skin as sanctified and sanctuary. Black skin as promise. Black skin as sermon and prayer.

If the work of Marshall helps to measure the distance of the journey—between people, identities, prejudices—then the profound and tender portraiture of Toyin Ojih Odutola (b. 1985) maps the mountainous sweep of that expedition. Gaze into her shimmering Black Fantastic—the grooves and juts and commotion of her Black figures, born of ballpoint and charcoal and pencil and pastels, the galaxies contained within their malleable exteriors. These are women and men unconcerned. Women and men not unlike those from her native Nigeria. Or from her transplanted home of New York City. They are free of shame and fear and contempt for people not like them. They are a gospel, a divine riot of the self. No, no. What I mean to say is much more simple. They are large and immeasurable.

“One of the things that I’m always trying to push for with the style that I employ is that Blackness impounds on our bodies, [is] housed in our culture, housed in our representations, our images, even status. It isn’t still, it’s material, it shifts,” Ojih Odutola told The Daily Beast in 2018. “And if you are going to impose this lie onto my very body, on my very skin, I’m going to show you how many layers of it lies there. And I am also going to reveal to you that the Blackness you impose is mine to do whatever I want with.”6 Layers accumulate, stack, spread, crack open. Layers turn into highways and forests. Into oceans. Into canyons of grief and roads to self-revelation.

In Like the Sea I, from 2013–14, Ojih Odutola sharpens her practice into the geography of self. She conjures her brother in her trademark ballpoint scripture—a heavy, inky black; bleeding reds; a delicate, understated gold. The body itself becomes a constellation of personal histories—because isn’t the self always in concert, always in a kind of negotiation with others, gaining and shedding, in a continual becoming?—and all that is contained rises to the surface, gleaming as it does, paradox and proclamation. But even this is not enough. This alone does not tell us all of what we yearn to know, or how to get there. Even at rest, the body toils, the body oscillates. What betrays the eye, what stands outside the reach of the painting—legs, elbows, feet—is just as critical to Ojih Odutola’s creative mission as what’s captured within its borders.

Let us map the body, let us make our way across its Black groves, tracking its history and creating our own. Let us journey beyond its limits and see what more we might unearth. “It’s a fascinating thing that people read Blackness as this contentious impenetrable territory,” Ojih Odutola said in the interview. “When in fact it is at most a nebulous tool.”7

Toyin Ojih Odutola

LTS I, 2013–2014

© Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

1. Tomkins, Calvin. “David Hammons Follows His Own Rules,” The New Yorker, December 9, 2019. www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/12/09/david-hammons-follows-his-own-rules.

2. Jafa, Arthur (director). Dreams Are Colder than Death, 2014. Los Angeles, California.

3. Rowell, Charles, H. “An Interview with Kerry James Marshall,” Callaloo, Winter 1998. www.jstor.org/stable/3300033?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Lucien, Lucy. “Toyin Ojih Odutola Challenges Blackness in Art—and Racism in Trump’s America,” The Daily Beast, January 29, 2018. thedailybeast.com/toyin-ojih-odutola-challenges-blackness-in-artand-racism-in-trumps-america.

7. Ibid.

PARHAM