Party leaders are commonly the focal point for discussion about politics and policy in Britain, as they are in many democracies. Elections, conference seasons, manifesto launches, TV debates, Prime Minister’s questions – in nearly every aspect of practical politics the media zooms its lens on the leader. Among the public, ‘Miliband’, ‘Farage’, ‘Cameron’, ‘Salmond’, ‘Clegg’, ‘Blair’ and ‘Thatcher’ are easy proxies for discussing the policies of the parties about which they often know less. Behind closed doors, leaders play a vital role in shaping the policy platform of their party, agree votes on parliamentary bills, negotiate post-election coalitions and pacts with their opponents, deal with rogue backbenchers, and represent their country in meetings with foreign leaders and international organisations.

Party leaders, therefore, matter. The fortunes of their party, their members and their country depend on them. A party leader without the communication skills to present their vision will never be taken seriously. A leader who fails to end internal divisions could leave their party out of power for a generation. A leader who makes key strategic errors could see the national interest damaged.

The Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle once claimed that ‘the history of the world is the history of great men’.1 This does overemphasise the transformative capacities that all leaders can have. They face constraints. Not all are capable of delivering change, leading an ill-disciplined party to electoral victory or reversing the course of history by themselves. But even in the most challenging of circumstances, they can make a difference, if only to steady a ship. To ignore how a skilled leader can re-shape their times is to misunderstand history, politics and society in Britain.

WHO IS BEST?

It follows that assessing political leaders is an important task in any country. Citizens should do this in a democracy to help hold their elected representatives to account and to ensure that their voices are heard. Parties should do this carefully to make sure that their electoral prospects are maximised. The questions are ever more important at a time when public disillusionment with politics and the political process has increased. But who have been the great leaders? How can we make a claim that they are ‘great’ objectively and impartially? What can parties and future leaders learn from past successes and mistakes?

In this book we address these questions by focusing on British Labour Party leaders from the time the party was founded up to Ed Miliband. Who was the most successful Labour Party leader of all time? And who was the worst?

If we were to just count general election victories, Harold Wilson comes top, with four. But does this tell the whole story? Clement Attlee frequently comes top of polls of the public, academics and even parliamentarians.2 Tony Blair’s record of three consecutive electoral victories must also put him in good stead. But then there are also the many other forgotten leaders. Take, for example, George Lansbury, who was described by the contemporary left-wing Labour MP Jon Cruddas as the ‘greatest ever Labour leader’.3 And what about Keir Hardie?

Drawing conclusions is made harder because even those leaders we may think of as great have their critics. Winston Churchill described Attlee as ‘a modest man with much to be modest about’.4 Wilson was criticised by Denis Healey for having ‘neither political principal’ nor a ‘sense of direction’.5 Blair is considered a ‘warmonger’ by many on the left for his decision to go to war in Iraq, and as a leader who too readily accepted free-market principles. Beatrice Webb, a contemporary of Lansbury, described Lansbury as having ‘no bloody brains to speak of’.6

THE TWO ‘C’S OF LEADERSHIP: CONSCIENCE AND CUNNING

It is suggested here that there are two overarching ways in which we can try to evaluate leaders. Much confusion comes about because spectators confuse the two approaches or are not explicit about the approach they have in mind and the contradictions between them.

The first approach is to evaluate political leaders in terms of whether they have aims, use methods and bring about outcomes that are principled and morally good. This is defined here as leadership driven by conscience.7 It involves an ethical and normative judgement about whether a leader’s imprint on the world is positive. Leaders are ‘better’, for example, if they strive to reduce poverty, increase economic growth or prevent human suffering; less so if they bring about needless war or economic decline, or fail to improve the lives of the impoverished. A leader led by their conscience will resist opportunities to further their own private position – be it the allure of office, prestige and power – if it is at the detriment of the public good.

Evaluations of Labour leaders in terms of conscience are ever present in discussions of Labour leaders, because of the history of the party. It grew out of the trade union movement and socialist political parties of the nineteenth century to represent the interests of the urban proletariat, some of whom had been newly enfranchised for the first time. The 1900 Labour Party manifesto therefore pledged maintenance for the aged poor, public provision of homes, work for the unemployed, graduated income taxes and more,8 as the party sought to, in Keir Hardie’s later words, bring ‘progress in this country … break down sex barriers and class barriers … [and] lead to the great women’s movement as well as to the great working-class movement’.9 Evaluations of whether leaders aimed to achieve conscience-orientated goals are found in this volume. For example, Kenneth O. Morgan praises Keir Hardie for setting out policy platforms on unemployment, poverty, women’s and racial equality and more. Phil Woolas praises John Robert Clynes for his ‘selfless political ego’ and commitment to improve the lives of millions of impoverished Britons. Brian Brivati heralds Hugh Gaitskell for not treating the Labour Party as ‘a vote-maximising machine’ and considers him to be ‘the last great democratic socialist leader of the Labour Party’.

Many leaders have faced criticism for supposedly deviating from conscience-orientated goals. The Labour Party’s history has been full of accusations of those ‘guilty of betrayal’ to the roots of the party – the workers, unions and voters. These criticisms accumulated as the twentieth century progressed, as the party moved to the centre ground and as leaders accepted economic orthodoxy. During the Second World War, in contempt of the stock and strategy of British politicians on the left, George Orwell blasted that the ‘Labour Party stood for a timid reformism … Labour leaders wanted to go on and on, drawing their salaries and periodically swapping jobs with the Conservatives’.10 These evaluations are well documented in this book. David Howell describes how the decision of Ramsay MacDonald, as Labour Prime Minister, to accept unemployment benefit cuts led to him being demonised for careerism, class betrayal and treachery. Neil Kinnock, as he himself describes in Chapter 20, was roundly criticised for having ‘electionitis’. For the Bennite left, Kinnock was ‘the great betrayer’.11 Even Ed Miliband, who, as Tim Bale suggests, was criticised for being ‘too left-wing’, was condemned for severing the link between the unions and Labour Party. Left Unity accused him of betraying the roots of the party.12 Of course, conscience-orientated criticism has also come from the right. The pursuit of socialist goals might stifle economic opportunity, insist liberals, conservatives and even some social democrats.

A second approach involves assessing leadership in terms of political cunning. This requires us to appraise leaders in terms of whether they are successful in winning power, office and influence. It forces us to introduce a degree of political realism into our evaluations. Leaders operate in a tough, cut-throat environment, where the cost of electoral defeat is usually their job and their party’s prospect of power. To survive, leaders’ goals can never be solely altruistic. They need to win elections and bolster their own position within their party and government if they are to achieve the grander aims they may have first set out in the field of politics to achieve. In trying to achieve policy objectives, they do so in an environment that can be hugely challenging. Some policy goals might have to be dropped as part of horse-trading within Parliament so that other legislation can be passed. ‘Accommodating’ the electorate by dropping policies that are an ‘electoral liability’ might not be heroic in the sense of conscientious leadership, but can be astute leadership in the cunning sense.

There is also a conscience/cunning contradiction at play when we consider the means leaders use to achieve their goals. Those concerned with conscience leadership might not want leaders to be underhand, break promises to the electorate or be disloyal to their parliamentary party or (shadow) Cabinet. But thinking about cunning leadership, we might, at least on occasion, recognise that these are necessary means to other ends if they secure the longer-term goals that we want: that piece of legislation passed to improve social welfare, or establish party discipline so that the party can fight an election on a stronger, united front or compromise with another party to secure a coalition.13 Harriet Harman recounted advice that she was given by Barbara Castle, who explained how she got the Equal Pay Act passed. Wilson’s government, Castle explained, was trying to get a Prices and Incomes Law with the narrowest of parliamentary majorities. Sitting on the front bench when the Speaker was making the roll call, Castle held a gun to her party and told them that ‘unless I get the Equal Pay Act, I am not voting for this’. ‘That is not very teamly, Barbara,’ replied Harman, but she subsequently reflected ‘that sometimes you need to play a little bit rough’.14 Those concerned with conscience leadership might warn us that ‘whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster’.15 But those concerned with cunning leadership warn that politics forces leaders to fight dirty sometimes.

Lastly, there is a conscience/cunning distinction at play when we think about the consequences of political leaders’ periods in office, in terms of whose interests leaders pursue. Those concerned with conscience leadership would demand that leaders should further the interests of the whole polity. They should not put any private interest, such as those of the individual, Cabinet or party, above those of the country.

Those concerned with cunning leadership, however, would champion the importance of furthering the interests of a particular group or section of society. The Labour Party, we should remember – like similar parties forged from the flames of industrialisation across western Europe and much of the rest of world – did not form to promote the general welfare of a nation. It began as a trade union movement to promote the welfare and interests of its own members. These were members of a particular class, based predominantly in manufacturing industries, and invariably those who were exposed to the harshest living and working conditions and absolute poverty. They defined their aims and interests in open opposition to those of employers and landowners. The policies they promoted may have benefited the national interest, but that was not how labour politics was framed.16 Leaders might be successful in maintaining their own position in power – this too would be cunning leadership.

CONSCIENTIOUS VERSUS CUNNING LEADERSHIP

Which is more important? Conscience or cunning leadership?

Our instincts are perhaps that conscience leadership is more important. A perception that leaders endlessly pursue the interest of their party above the country arguably has contributed towards public distrust of politicians, political leaders and politics. Yet the reality of politics is that it does involve compromise and strategy. Evaluating leaders in terms of conscientious leadership alone is therefore obviously problematic.

The case for evaluating leaders in terms of cunning leadership is three-fold.

Firstly, such evaluations are easier to conduct in objective terms. Discussions about what constitutes conscience leadership are inevitably normative and these debates can be conveniently set aside. After all, is the conscience economic policy one that limits environmental degradation or one that promotes economic growth to alleviate poverty? Does it promote state provision of health care or private enterprise? Each of these requires difficult judgements that should be considered in detail elsewhere, and they require the tools of the economist, philosopher and more.

Secondly, nothing can be achieved without power and office. The Labour Party took twenty-four years to be in government after it was founded. It was out of office for eighteen years following James Callaghan’s defeat in 1979. At the time of writing, the party is set to be out of power until at least 2020. During these times of political wilderness, leaders are typically incapable of bringing about progressive social change because of the winner-takes-all nature of British government. It is therefore necessary for political parties who are trying to choose their party leaders and decide upon a future political strategy to think about political leadership in terms of political cunning.

Thirdly, there are also advantages for the citizen of evaluating leaders in this way. If all parties are sufficiently politically competent, then democratic politics should be a more competitive process, giving the voter better choice. As Neil Kinnock remarks in Chapter 20, leaders of the opposition play a vital role in servicing democracy by providing an alternative government.

Moreover, if civil society better understands the challenges leaders face, why they were (un)successful in winning office and how any imperfections and injustices in democratic politics bring about this outcome, then it will be better positioned to prescribe democratic change and support more conscience leaders. Civil society is not always equipped with knowledge about the inner workings of government in the way that elite politicians and parties are. Evaluating leaders in statecraft terms can therefore encourage us to think about the health of democratic politics and to redress any shortcomings. Of the poor leader who still won elections, it makes us think: how did they get away with it? Of the good leader who overcame numerous challenges, it makes us think: how did they manage that?

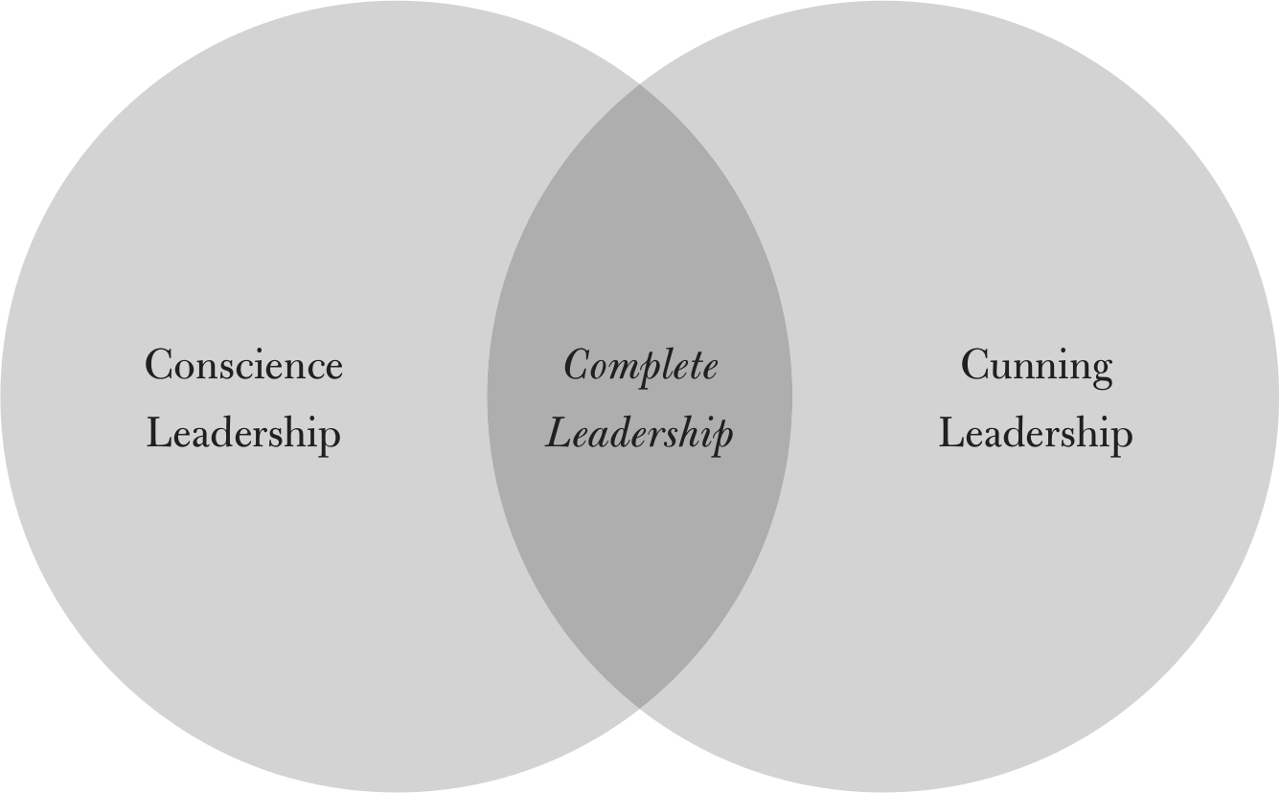

THE THIRD ‘C’ OF LEADERSHIP: COMPLETE LEADERSHIP

Conscience and cunning leadership are, of course, not mutually exclusive. theoretically, leaders can achieve their conscience goals, means and consequences with political cunning. this is no small feat. to manage a political party, develop policies, pass legislation, outmanoeuvre the opposition and form electoral coalitions when necessary – without compromising conscience goals, using unscrupulous methods or putting personal/party interests above the interests of the nation – might be unfeasible. But, theoretically, it is possible, and we can think of leaders who achieve this as being complete leaders.

FIGURE 1.1: CONSCIENCE, CUNNING AND COMPLETE LEADERSHIP.

There is reason to think that, since the time when the Labour Party was first founded, leaders have been under increased pressure to achieve both conscience and cunning leadership. in 1900, the franchise was limited to men with wealth, and levels of education were comparatively low. A winning electoral strategy could, therefore, be wilfully neglectful of much of the country. Today, Britain is a democracy in which all citizens can vote, and the widespread availability of the press allows ideas to be exchanged and debated. In a democracy, being a conscience-focused leader should therefore deliver you electoral dividends. As Charles Clarke argues in Chapter 3, a general election is, in many ways, a fair test of the leader.

But there are still flaws in British democracy: the media is often thought to have undue influence; electoral laws can give advantage to political parties; corporate power gives uneven political influence; citizens have limited knowledge of and interest in politics and policy; and incumbency gives a government the opportunity to use the state for political purposes. An unscrupulous leader might win office because of these injustices. Convinced that Thatcher was of this ilk, many on the left and in the centre of British politics in the 1980s argued for radical constitutional reform under the rubric of Charter 88.17

THE BOOK AHEAD

Having now introduced the puzzle, in the next chapter of this book, Jim Buller and I introduce a framework for evaluating leaders. This suggests that we should assess leaders by statecraft – the art of winning elections and achieving a semblance of governing competence in office. Not all Labour leaders were prime ministers – some did not stay in power long enough to fight a general election, and, for others, winning office was never likely. But we can still assess them in terms of whether they moved their party in a winning direction. The statecraft approach also defines the key tasks leaders need to achieve in order to win elections. This is helpful because it allows us to consider where they might have gone wrong. The approach focuses firmly on cunning leadership.

After the statecraft framework is outlined in Chapter 2, Charles Clarke then evaluates the success (or otherwise) of Labour Party leaders at election time in Chapter 3. Using data on the seats and votes that they have won or lost, he compiles league tables to identify those who have been successful and those who have not. This chapter therefore gives us an important overview of the electoral fortunes of Labour leaders since the party was founded.

Subsequent chapters then provide individual assessments of each of the Labour leaders. The authors of each chapter are all leading biographers of their subject. Biographers were deliberately invited to contribute towards the volume as they can paint a picture of the context of the times and the political circumstances in which their subject was Labour leader. The biographers were not asked to directly apply the statecraft approach, but to describe their leader’s background on the path towards the top position, as well as the challenges the leader faced and how successful they were in electoral terms. Many assessments go beyond examining the political cunning of leadership and also include judgements in conscience terms. They therefore, collectively, provide a rich set of evaluations from leading scholars and commentators.

Table 1.1 provides a summary of the authors’ (though not necessarily the editors’) assessments in statecraft terms. Many of the early leaders were deemed to be a success. Keir Hardie is praised for being a pragmatic strategist who concentrated political efforts on increasing Labour representation in Parliament, which in turn laid the road to power. John Robert Clynes was at the helm for the great breakthrough in 1922; Ramsay MacDonald was the first to win office. Of the modern leaders, Harold Wilson, argues Thomas Hennessey, has an almost unrivalled electoral record, while Tony Blair, asserts John Rentoul, had an intuitive feel for public opinion, possessed natural communication skills and devised a successful winning electoral strategy.

Gaitskell, Callaghan, Foot, Brown and Miliband, the biographers generally accept, were failures in statecraft terms. Claims for success, if there are any, instead lie largely in conscience terms (in the case of Gaitskell and Foot), or in their contribution before they were leader (in the case of Callaghan and Brown).

Clement Attlee is perhaps a surprise inclusion in those leaders who are given a more mixed assessment. Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds provides a robust argument in favour of Attlee in conscience terms – it was under Attlee that the modern welfare state and the National Health Service were created – but argues that Attlee failed to provide leadership on issues such as the devaluation crisis of 1949, and that he had a naive approach to the electoral boundaries, which undermined his statecraft.

TABLE 1.1: LABOUR LEADERS’ STATECRAFT SUCCESS AND FAILURES, 1900–2015.

| Great | Mixed | Poor |

| Keir Hardie John Robert Clynes Ramsay MacDonald Harold Wilson Tony Blair |

George Nicoll Barnes William Adamson Arthur Henderson George Lansbury Clement Attlee Neil Kinnock John Smith |

Hugh Gaitskell James Callaghan Michael Foot Gordon Brown Ed Miliband |

In the final chapters, we take an original approach by asking the leaders for their own perspectives on leading the Labour Party. The book therefore includes two exclusive original interviews: Neil Kinnock, who led the Labour Party 1983–92; and Tony Blair, leader 1994–2007. In the interviews, we ask them about their path towards the office of leader, the challenges they faced, whether they think the statecraft framework is a ‘fair’ test of a leader, and how they would rate themselves using that model. These interviews are of important historical value for those wanting to understand past leaders’ tenures. They also provide lessons for future leaders. Moreover, they allow practitioners of politics to join in the conversation with academics, whose ideas might otherwise be left in ‘ivory towers’. This type of conversation can only improve our understanding of the quality of leadership and leaders’ understanding of the scholarship on it.

1 Thomas Carlyle, ‘The Hero as Divinity’, in Heroes and Hero-Worship, London, Chapman & Hall, 1840. Carlyle’s quote obviously implicitly embodied the discriminatory assumption about the role of women in history. Sadly, there have been no female Labour leaders yet.

2 See Charles Clarke’s discussion of such polls in Chapter 3.

3 Jon Cruddas, ‘George Lansbury: the unsung father of blue Labour’, Labour Uncut, 5 August 2011, accessed 29 May 2015 (http://labour-uncut.co.uk/2011/05/08/george-

lansbury-the-unsung-father-of-blue-labour).

4 Cited in Chris Wrigley, Winston Churchill: A Biographical Companion, Santa Barbara, CA, ABC Clio Inc., 2002, p. 32.

5 Cited in Kevin Hickson, The IMF Crisis of 1976 and British Politics, London, Tauris Academic Studies, 2005, p. 48–9.

6 See Chapter 9.

7 This discussion builds on the distinction made by Joseph Nye, The Powers to Lead, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 111–14.

8 The Labour Party, ‘The Labour Party General Election Manifesto 1900: Manifesto of the Labour Representation Committee’, in Iain Dale ed., Labour Party General Election Manifestos, 1900–1997, London, Routledge, 2000, p. 9.

9 Keir Hardie, ‘The Sunshine of Socialism’, speech delivered at the twenty-first anniversary of the formation of the Independent Labour Party in Bradford, 11 April 1914, accessed 29 May 2015 (http://labourlist.org/2014/04/

keir-hardies-sunshine-of-socialism-speech-full-text).

10 George Orwell, The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius. Part 3: The English Revolution, London, Secker & Warburg, 1941.

11 Francis Beckett, ‘Neil Kinnock: the man who saved Labour’, New Statesman, 25 September 2014.

12 Bianca Todd, ‘Labour has betrayed its roots by distancing itself from the unions’, The Guardian, 3 March 2014, accessed 29 May 2015 (http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/03/

labour-party-unions-left-unity-ed-miliband).

13 Cunning leadership does not necessarily require deceit – but cunning leaders should not be criticised for using it. The contemporary meaning of the word ‘cunning’ does imply dishonesty. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as ‘skill in achieving one’s ends by deceit’. As the same dictionary notes, however, this was not always the case. The term has its origins in Middle English (‘cunne’) and the original sense of the word had no implication of deceit – it implied knowledge and skill. Source: Angus Stevenson, Oxford English Dictionary (third edition), Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010.

14 Harriet Harman, ‘Harriet Harman in conversation with Charles Clarke’, lecture at the University of East Anglia, 22 January 2015 (http://www.ueapolitics.org/2015/01/23/

harriet-harman/).

15 Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, New York, Random House, 1966 [1886], sec. 146.

16 Over time, of course, the party evolved to develop a broader appeal as class cleavages were perceived to have declined. Ed Miliband rebranded the party as ‘One Nation Labour’ in 2012. See: Roy Hattersley and Kevin Hickson. The Socialist Way: Social Democracy in Contemporary Britain. London, I. B. Tauris, 2013, p. 213.

17 David Erdos, ‘Charter 88 and the Constitutional Reform Movement Twenty Years On: A Retrospective’, Parliamentary Affairs, 64(4), 2009, pp. 537–51; Mark Evans, Charter 88: Successful Challenge to the British Political Tradition?, Aldershot, Dartmouth, 1995.