If you want to manage somebody, manage yourself. Do that well and you’ll be ready . . . to start leading.

—ANONYMOUS

It is essential for managers to model and communicate the appropriate rules of proper engagement to all the people who work on the team. Developing the skills of active listening, mindful empathy, and giving full attention to each other in conversation ensures a civil culture. If someone is exhibiting bullying behavior, you must address his actions directly. The proper mindset preparation, documenting critical incidents, and writing scripts are valuable and applicable when dealing with a bully on a team and can become part of the performance review process. Preparing a script to reprimand someone after a specific bullying event or if the behavior becomes too egregious is vital. A manager should be recording her own critical incidents when dealing with the bully. You may need to bring in others to assist, including human resources.

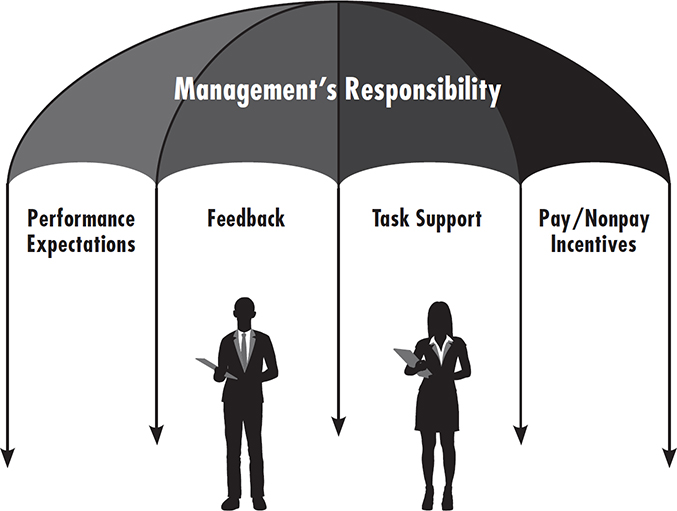

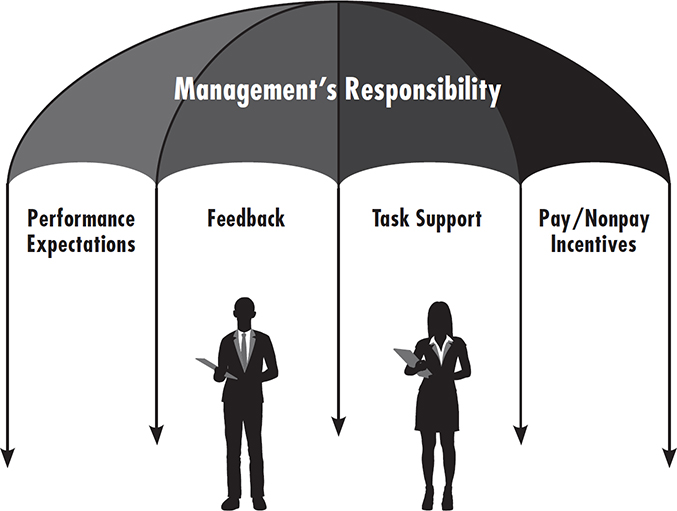

Before we prepare to engage the bully, let’s look at the managers’ responsibility in the execution of their duties as leaders, which is essential for a bully-proof workplace. Managers manage, but the managers have to lead as well, requiring different skills with either effort. The chart in Figure 8.1 features the four areas of a manager’s responsibility. A good manager enables workers to use their full knowledge, skills, and capabilities.

FIGURE 8.1 The Four Areas of a Manager’s Responsibility in a Bully-Proof Workplace

Potential bullies can start down the road toward bullying if they are operating from the lack of any one of the four categories of support that managers must provide to help their people meet the optimal level of job productivity. The categories are clear expectations, direct feedback, fair and appropriate support for tasks assigned, and pay and nonpay incentives. A potential bully might take the absence of these pillars of support personally as a slight; begin to misperceive the situation as unfair, which triggers his insecurities; and then start to retaliate against a subordinate or peer.

The following questionnaire has been adapted from one that appeared in Thomas Gilbert’s book Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance.1 A manager should answer the following questions to create a fair, productive, and bully-proof workplace. They are designed to identify areas of the work, work procedures, or work environment that are required for proper management.

Please respond yes or no to each item as it relates to your reports. For each no response, please recognize that your answer demonstrates a lack of connectivity with employees and should be addressed. If you give the survey to your employees and receive back more than five no responses, you must attend to it. It is management’s responsibility to work toward creating the conditions to enable employees to answer yes to all these questions.

Using the following questions to optimize effectiveness and efficiency, management has to set expectations, build feedback systems, allocate task support, align processes and procedures, and decide on pay and nonpay incentives.2

• Are directions readily available to help experienced employees perform well?

• Are directions clear enough to help experienced employees perform well?

• Are directions accurate?

• Are directions free of confusion that slows performance and invites error?

• Are directions free of “data glut,” and are the directions stripped down to their simplest form?

• Are directions consistent with good training practices?

• Are directions given in a timely manner?

• Do employees have all the information they need to do their job well?

• Are clear and measurable performance standards communicated so that employees know how well they are supposed to perform?

• Do employees believe the standards are reasonable?

• Does work-related feedback provided by employees describe results consistent or inconsistent with expectations?

• Does work-related feedback provided by supervisors describe results consistent or inconsistent with expectations?

• Is feedback immediate and frequent enough to help employees remember what they did?

• Is feedback selective and specific—limited to a few matters of importance and free of data glut and vague generalities?

• Is feedback educational—positive and constructively informative so that employees can learn from it?

These tools include such supports as accurate scheduling, planning, allocations, resources, reference materials, and anything available to do a job well.

• Are there necessary tools, equipment, procedures, and task support available for the job?

• Are they reliable and efficient?

• Are they safe?

• Are procedures efficient, and do they avoid unnecessary steps?

• Are they based on sound methods rather than on tradition?

• Are they appropriate to the job and skill levels?

• Are they free of boring repetition?

• Are materials appropriate to the job?

• Is time sufficient to do the job well?

• Are the training and work areas conducive to being productive?

• Do employees complain about tools, equipment, and facilities? If so, what do they complain about?

• Is the pay for the job competitive?

• Are bonuses or raises given? Are they based on good performance?

• Does good performance bear a clear relationship to career advancement?

• Are meaningful nonpay incentives given, based on good results—not completion of assignments?

• Are nonpay incentives so infrequent as to be meaningless?

• Is good performance free of punishing consequences, such as peer pressure on employees who are successful or being asked to “pick up the slack” for someone else when they have finished a project early?

• Is the work environment free of incentives to perform poorly, such as praise for designing, developing, and delivering a project in record time without regard to content required for the project?

• Does a balance of positive versus negative incentives encourage good performance?

As John P. Kotter emphasized in Accelerate, management is critical, but it is not leadership.3 Leadership is associated with taking the organization into the future by setting the vision for work through exemplary communication skills and the ability to adapt and not let ego get in the way, collaborating with others, integrating proper standards into decision-making, eliciting commitment from others by modeling proper interpersonal engagement skills, and having productive and positive relations with those who do the work. The following checklist unpacks the skills leaders need to master.

Do managers receive training in dialogue skills when promoted into management?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they actively listen conscientiously with openness and agreeableness?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they empathize with others and not let their ego overshadow the conversation?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they attend to others and be receptive to how they think, feel, and behave?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they diagnose, detail, discern, and make decisions with relative ease?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they engage others without losing emotional composure?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they remain respectful and resilient in times of conflict and when others vie for power?

Yes ___ No ___

Do managers receive training in interpersonal interactive skills when promoted into management?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they speak to groups or to an individual with specificity and clarity?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they communicate a problem directly so as not to project judgment or negativity?

Yes___ No ___

Can they communicate a problem specifically, stating what is expected and what is observed?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they communicate a problem in a nonpunishing and nonthreatening way?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they communicate a compelling message in which words, vocal tones, and facial expressions are aligned?

Yes ___ No ___

Do managers receive training in how to use their power when promoted into management?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they appropriately use position power without being coercive, inducing fear, or overusing sanctions?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they appropriately use political power without taking credit away from others or being insensitive?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they appropriately use interpersonal interactive skills without projecting negativity?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they appropriately use personal power skills: self-discipline, interest in people, and ability to provide feedback?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they appropriately use intrapersonal power skills: willingness to adapt, keep focused, and be engaged?

Yes ___ No ___

Do managers receive training in team skills when promoted into management?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they successfully complete tasks by:

Initiating new ideas?

Yes ___ No ___

Seeking information?

Yes ___ No ___

Seeking the opinion of others?

Yes ___ No ___

Sharing information?

Yes ___ No ___

Giving a true opinion?

Yes ___ No ___

Elaborating or clarifying ideas through examples or analogies?

Yes ___ No ___

Summarizing everyone’s ideas?

Yes ___ No ___

Can they successfully:

Maintain positive relations with others?

Yes ___ No ___

Encourage the contributions of others?

Yes ___ No ___

Set the standard for positive expressions?

Yes ___ No ___

Facilitate the contributions of others by ensuring equitable talking time?

Yes ___ No ___

Summarize the group’s feelings and reactions?

Yes ___ No ___

Do they avoid antiteam bullying behaviors such as:

Aggressively criticizing to deflate the status of others?

Yes ___ No ___

Blocking progress by rejecting all new ideas?

Yes ___ No ___

Seeking excessive recognition by talking loudly or interrupting others?

Yes ___ No ___

Cutting off other speakers to block their flow of ideas?

Yes ___ No ___

Any no answer compels the manager to address the item with her reports.

Every manager needs to be aware of the behaviors that help develop a team so that he can manage and lead in an exemplary manner. In research conducted with physician leaders in the Physician Executive MBA program at the University of Tennessee, five distinct stages of team development were identified: novel politeness, goal clarity, vying for voice, constructive communication, and collaboration.4 Within these stages are the management and leadership skills designed to replace the antiteam bullying behaviors. We have refined these stages over the years in our attempts to help executives develop leadership teams for their organizations.

This stage of the team process has more to do with self-orientation than with teamwork. It is characterized by the following behavior: tentative, reserved, measuring each other as they search for information about each other, learning about and from each other, confusion and frustration in communication, and experiencing self-doubt along with growing self-confidence. A group begins to form only when feedback from each other and from management about performance is introduced in the process.

During this second stage the attention of each member of the group shifts from a self-orientation to an external objective. Only with feedback that demonstrates the gap between the observed performance of the members and the expected performance does the team transition. When the challenge of the goal is clear and the criteria for the kind of and degree of learning necessary is also clear, the group begins to orient itself to the task at hand. The second stage is still one of orientation, but the difference is that the group has received the direction to success. Soon after this group realization, when the energy of the team has been focused, a third stage emerges.

When the energies of the members of the group begin to move in the same direction, there are also likely to be some exchanges among members that can be called by another name—conflict. Conflict results from different agendas and ways of doing things. There will undoubtedly be bids for power over the group and within the group. In this third stage, adversity and diversity in thought and action emerge as often as persuasion and provocation.

This third stage is the greatest challenge for the group. But conflict is normal, and dealing with it successfully helps the group bond into a team. The group must persevere through this stage if it is ever to become a team. The convergence of individually based norms of behavior that are centered on self-interest has to be reconciled with the more universally accepted norms of behavior that ensure fairness and equal dignity to each person.

This stage never goes away completely as the team development process continues. Vying for voice is key to the success of the team. It adds integrity to the team process because each team member can express his or her opinion. Depending on the level of resolution of the conflict between self-interest norms and universal norms in different areas of concern, members usually report different outcomes. Not surprisingly, better communication, greater respect, and sharing of information occur when a greater number of team members have reached consensus on the direction of the action to be taken.

In this stage true team behavior is exhibited. Individual egos are still active, but in greater awareness of a common mission. Here every individual can contribute, will be listened to irrespective of the intensity or diversity of her voice, and the problem will be worked through until a majority has reached a consensus. Working through the problem ensures optimal learning about the problem itself. As this becomes more characteristic of a team, there emerge real moments of synergy.

This fifth stage may not actually be a stage at all as reports indicate that it comes and goes seemingly on its own. The longevity or brevity of this stage is not dependent on individual behavior but on the synchronicity of a team’s behavior. In fact, one team member has remarked that the harder you try to maintain it, the faster you lose it.

It is interesting to note that reports of this kind of experience occurred more in subteams than in large teams of 20 or more. When it is present, it speaks to a team’s overall discipline, determination, and dedication to making the best decisions that can be made—and not any individual behavior or series of individual behaviors.

• Novel politeness (requires management): Team members are tentative, measured, and confused, and they experience some self-doubt. This has more to do with self-orientation, but it is necessary for team development.

• Goal clarity (requires management): There is a shift to an external objective that is clear in its expectation.

• Vying for voice (requires leadership): Conflict occurs as differences in thinking, planning, doing, and leading emerge.

• Constructive communication (requires management and leadership): Team members practice listening and empathy, and they move toward consensus collaboratively.

• Synergistic collaboration (requires leadership): Power is shared so as to get things done, and this stage is characterized by emotional strength and good ego management. Also, there is an effortless process in which there is discipline, determination, and dedication to the team and its task.

With good management and leadership practices in place, if bullying emerges, the manager, confident that he has fulfilled his responsibilities, can address it effectively. First, the manager will document critical incidents in order to identify what type of bully he is dealing with, and then he will develop a script based on the critical incidents.

With ignorance comes fear—from fear comes bigotry. Education is the key to acceptance.

—KATHLEEN PATEL, The Bullying Epidemic5

We all have the instinct for survival. It is part of our psychological makeup. This survival instinct can cause us to be impatient, devious, controlling, self-absorbed, self-adoring, and lacking in self-discipline and impulse control. These behaviors are the same behaviors that are manifest in the four types of bullies—except that bullies have taken it to an extreme, targeting others and causing them emotional, mental, or physical harm.

Almost all of us:

• Have bullied another person, sibling, friend, peer, or someone else at some point in our lives in one of the four ways.

• Have passed along half-truths.

• Have blocked someone from contributing her ideas.

• Have been instinctively inappropriate in our interpersonal exchanges.

• Have maneuvered the attention of the conversation back to ourselves.

• Have been overly forceful, rolling over another person and his ideas.

If these behaviors are infrequent incidents, even though not ideal, they are not bullying per se. If the incidents become exacerbated, fester, and become chronically routine with the purpose of demeaning and devaluing another and decreasing that person’s productivity or success on the team, it becomes bullying. We all have a responsibility not to become a bully. Once we have owned that responsibility and accepted that we have to monitor ourselves, we can recognize the natural human tendency to grow and develop. Focusing on this tendency allows our personal worth and self-confidence to increase with each positive accomplishment.

Bullies mask their fears with disorderly behaviors meant to cover up their insecurities and jealousies, thus denying themselves a chance to grow and develop. They harbor fears of failure, rejection, being wrong, being weak, being ignored, not being able to change fast enough; feelings of inferiority, insecurity, or being an imposter; jealousy, extreme fear of being vulnerable and loss of control; or traumatic, emotionally significant past experiences. They may be projecting their differences in values, beliefs, or unconscious biases.

Bullies may be acting from any number of other root causes: a lack of training in how to get along with people without crossing boundaries; anxiety about a difficult task; an unseen power struggle with someone in the company; unmet personal expectations; a general state of rebellion; different manners and etiquette learned from family patterns; self-consciousness about their accents and language differences; or a host of other personal problems and stressors. It also may be because they lack other skills, such as delegation, decision-making, communication, problem solving, resilience, and endurance.

These are not excuses for the bully. Knowing this kind of information about someone on your team who is bullying others is valuable as you, the manager, can bring in a coach to help with either training or coaching.

Bullying behavior starts in the mind of the bully as a negative emotion. If it is not properly processed by the person there and then, it can fester into a mental judgment about someone. This is targeting. Once a target has been identified, the bully will begin to process justifications for projecting that negativity onto the person. The bully’s mind is then mostly closed to any value the target may or may not bring to work. Bullying behavior soon appears. It is a negative emotion projected, usually aggressively, onto others without true justification. Often the bully has created false evidence in his own mind that he has accepted as truth. Once that happens, not only does bullying behavior emerge but it becomes very difficult to reset the relationship.

No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.

—ELEANOR ROOSEVELT

We all have fears. Fear triggers anxiety. We all experience anxiety. Anxiety triggers our survival instinct, causing us to experience a fight, flight, or freeze modality. If we allow ourselves to be dependent when we are being bullied, we may acquiesce to the bully and not stand up for ourselves. If we choose to flee the scene of bullying, which many of us opt to do, we carry the stress of that experience with us to the next scene. If you choose to fight, this book is invaluable to you.

We also have a list of seminars in the Appendix that we suggest using to back up coaching. As coaches, we try to help bullies identify the underlying causes for their aberrant behavior. Often the boss of the bully is involved in the coaching. The bullies need training on how to use both management and leadership in their style, and they must gain an understanding of the use of power, influence, empathy, and resilience, as well as dialogue and communication skills. When bullies resist development in these areas, they usually derail their career because of their need for immediate gratification, inability to accept feedback or coaching, and unwillingness to look within themselves.

For those who choose the natural tendency toward growth as managers and leaders, it begins with having patience in their own development, learning how to self-reflect, being willing to accept feedback and coaching, and choosing to invest in themselves by developing positive relations with others.

What seems to be of the utmost importance to humans is how we feel about who we are. We long to look good in the eyes of others, to feel good about ourselves, to be worthy of others’ care and attention. We share a longing for dignity—the feeling of inherent value and worth.

—DONNA HICKS,

Dignity: Its Essential Role in Resolving Conflict

There are two ways managers can deal with the sociopath on the team in order to create a positive team environment. First, they can decrease and eliminate the toxic, antiteam behaviors and replace them with team-building behaviors. Second, they can increase task and relationship synergistic team practices. We have already shared suggestions for engaging a bully one-on-one. Now we will focus on team skills.8

The nonfunctional, toxic behavior by either the manager or members of the team that do not help create a team environment include the following:

• Aggressively criticizing, being hostile, or deflating others’ sense of worth

• Blocking progress by rejecting all ideas; arguing and controlling too much

• Confessing personal feelings about non-group-related issues

• Competing for attention by talking too much so as to be seen as the best

• Soliciting sympathy for one’s own situation, problems, or misfortunes

• Seeking recognition by excessive, loud talking about extreme ideas

• Seeking special attention for pet concerns or philosophies

• Disrupting progress by joking, mimicking, or teasing others

• Disengaging by doodling, whispering, or daydreaming

• Spreading false rumors and naysaying after a meeting

• Cutting off speakers

• Constantly changing focus by wandering off topic

These behaviors slow down and prevent a group from becoming a team. They need to be eliminated and replaced with the following team-building task behaviors. On a high-performing team, the responsibilities of management and leadership can be shared with all members of the team.

• Comparing decisions and accomplishments against group goals

• Analyzing, discerning, and determining main blocks to progress

• Taking measured steps to eliminate difficulties preventing progress

• Testing consensus by asking for individual and group opinions

• Harmonizing and conciliating differences of opinion in public

• Mediating for compromised solutions and steps forward

• Initiating new ideas and new ways to reframe a problem to solve it

• Seeking information and additional facts for clarification

• Soliciting opinions, feelings, or clarifications of values

• Sharing information, facts, illustrations, and examples to help clarify

• Offering an opinion, a belief, a suggestion, or a value

• Elaborating on or clarifying a task

• Showing a coordinated relationship among various tasks and ideas

• Summarizing everyone’s ideas and suggestions by vocalizing them

• Encouraging the contributions of others with praise and civil responses

• Setting a standard for positive individual expressions and group decisions

• Responding with positive regard to the good ideas of others as they emerge

• Facilitating the contributions of others by ensuring equivalent talking time

• Summarizing the group’s feelings and reactions to ideas proposed

• Relieving tension by using humor to dispel negative feelings

• Relieving tension by presenting the situation in a wider context

Coming together is a beginning; keeping together is progress; working together is success.

—HENRY FORD

Teams are an integral part of an organization. Teams fail to develop when there is little trust, fear of speaking much less confronting, a tendency to avoid conflict, low levels of patience, too much control of contributions, and little to no feedback on the impact of interpersonal exchanges. These conditions foster bullying in the workplace.

The benefits of a positive team environment are many. When individuals on a team are encouraged to examine opposing viewpoints, they often find themselves challenged to defend their ideas. Working through this type of controlled conflict in an atmosphere of trust can transform rivals competing with each other to rivals acting on their best knowledge and know-how in synergistic collaboration. As problems are solved by the group, the result is work that has been fully considered and, in essence, pretested through greater disclosure, feedback, listening, and loyalty by every member of the team. As economist, management guru, and author Peter Drucker said, “No executive has ever suffered because his subordinates were strong and effective.”

According to a 2013 report by Gallup, there are three categories of engagement: fully engaged, in which workers are positively and emotionally connected to the work, are energetic, are productive, and have good working relations with their managers; not engaged, in which workers do not invest emotional energy in their work and more or less sleepwalking through the workday; and actively disengaged, in which workers are using their energy for everything else but accomplishment of work or just complying to avoid punishment.9

In both cases, the not engaged and actively disengaged are disconnected from their work, and their full attentive powers are dampened. Although there may be many reasons for this unproductive situation, there is often one common reason: the workers’ relationship with the manager. If the manager is a bully, this often results in a loss of productivity and workers becoming actively disengaged or not engaged at all if they can get away with it. The Gallup report suggests that up to 70 percent of American workers are not engaged or actively disengaged. Even though there may be other contributing factors, we know from our coaching and consulting experience that the cause is often a negative relationship with a bully manager.

Moreover, with the move from hierarchical company structures to flatter, globally distributed networks where the work is customized, requiring greater communication and collaboration, and with the increase of generation X and millennials in the workforce who desire to work anytime and anywhere, crafting their own work output, we see the increase in bullying behavior as the last-ditch attempt by traditionalists and baby boomers to control the changes at work. The workplace itself is in transition.

As Jacob Morgan suggests in his book The Future of Work, employment and management are fundamentally changing in the direction of manager-less companies.10 The employees want to have the potential to become leaders in their work, as everyone now can be leaders even without a managerial title. It is almost as if bosses are at a crossroads. They can adapt or bully. The managers who are adaptable will learn to lead by example and use control only as a last resort. Others will cling to direct or indirect bullying behavior, refusing to leave the bunker from which they believe they can control the workplace.

When up to 60 percent of our adult lives are spent at work, we are inclined naturally to want to get better and better at what we do. Usually, we want to be given the freedom to perform at our best without the obstacles of managerial control or bullying behavior.

Human beings have a natural tendency and a productive capacity to grow, to develop, and to accomplish good works, and we all tend to gravitate toward opportunities in which we have the room and encouragement to grow.

Not being able to fulfill our potential and feeling that our growth is being held back because we are being bullied is like experiencing little deaths each day. Work should be purposeful for the company and meaningful for the individual, and it should support the natural human tendency to grow and develop.