5

THE SELF-FULFILLING PROPHECY AND THE ‘PEOPLE’S WAR ON TERROR,’ 2013–2016

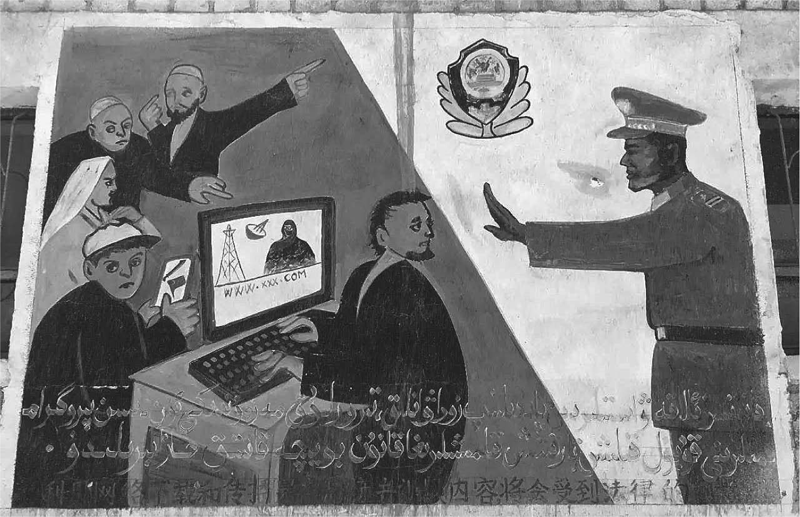

5 ‘Counterterrorism’ mural in village near Kuqa, 2014. The mural reads, ‘The use of the internet to download and disseminate violent terrorism audio and video content will be subject to severe legal punishment.’ © Zheng Yanjing.

On 29 October 2013, an SUV with a black flag bearing the Shahadah waving outside one of its back windows drove recklessly towards the Forbidden City in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, struck numerous people, and caught fire near the palace that has long symbolized Chinese power. It turned out that a Uyghur family had been inside the vehicle, including a man, his wife, and his mother. Five people were killed, including those in the car and two tourists, and thirty-eight were injured in the process.1 This was the first time that the gradually escalating violence inside the Uyghur homeland had spilled into inner China, and, as such, it helped to escalate the fear of the alleged ‘terrorist threat’ posed by Uyghurs inside the PRC to a new level.

At the time, I was asked by CNN.com to write an opinion column on the incident, and in that piece, I raised skepticism about this event’s connection to an organized threat with ties to international ‘terrorism’ networks, given the rudimentary nature of the attack.2 The response I received from Chinese netizens was overwhelming and extremely violent, many sending me death threats by email. Most were incensed that an American could not recognize the equivalency between Uyghur-led violence in China and the 9/11 attacks on the US, and a few even justified policies vis-à-vis Uyghurs because ‘the US had done the same thing to Native Americans.’ The Global Times wrote a scathing editorial about my column, criticizing CNN for publishing it, and CCTV, China’s state broadcaster, aired a seven-minute segment that suggested that CNN had ‘an ulterior motive’ in questioning whether this attack was terrorism.3 Chinese citizens even started a supposedly grassroots campaign to ban CNN from the country.4

While this incident garnered much attention given that it had occurred in the symbolic center of state power, it was not anywhere near the most violent incident involving Uyghurs in China in 2013. The self-perpetuating ongoing violence in the south between security organs and local Uyghurs that had begun in 2010 had been escalating throughout 2013 and had already taken far more lives than the five lost in Beijing, but it had been isolated in the Uyghur region and had mostly gone unreported by the state. It is much more likely that the incident in Tiananmen Square was an outgrowth of the tensions of this ongoing violence between security organs and Uyghurs in the south of the Uyghur homeland than being related in any way to ‘international terrorism.’ However, the Chinese state was adamant that the incident was an obvious ‘terrorist attack’ that was masterminded by TIP’s adherents inside China. While TIP issued a video that congratulated the Uyghurs who had carried out what it characterized as an act of jihad, it did not take responsibility for the act or claim any specific linkage to it.5 Furthermore, the actual circumstances around the crash were unclear and certainly did not suggest a well-organized attack. While the black flag bearing the Shahadah flying outside the car window suggested at least a familiarity with the symbols of militant Islam, a husband, wife, and mother constituted a strange make-up for an alleged ‘terrorist cell’ aligned with international jihadist groups. Furthermore, other sources speculated that the family was possibly intentionally killing themselves rather than others, akin to Tibetan self-immolations, to protest the destruction of a mosque in their hometown in Akto a year earlier.6 Regardless of the actual motivations and intentions for the family’s SUV crash into Tiananmen Square, it suggested that the self-perpetuating violence between disenfranchised Uyghurs and the state was not only having ramifications beyond the southern Tarim Basin, but beyond the Uyghur homeland itself.

Thus, by late 2013, it seemed that the concerns about Uyghur political violence that the PRC had over exaggerated and had labeled as a ‘terrorist threat’ throughout the previous decade were perhaps finally becoming a reality through a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy.’ Furthermore, this violence would increase over the following three years, with some of the incidents appearing to legitimately qualify as ‘terrorist acts’ by the working definition of this book. However, none of these developments suggested that there was any organized ‘terrorist threat’ within China’s Uyghur population, let alone one that was connected to TIP or any other international jihadist group. Instead, almost all of the incidents appeared to have their own local peculiarities that informed their motivations and intentions. However, the fact that so many acts of violence were being carried out in isolation from each other was also indicative of how widespread the frustration and rage had become within the Uyghur population, especially in the rural south.

The PRC predictably responded to this increase in violent resistance once again with an escalation of its own state-led violence, which it justified in the name of ‘counterterrorism.’ While the next three years through 2016 would witness continued state-led efforts at ‘expediated development’ in the Uyghur homeland through the PAP, this development would be gradually overshadowed by the PRC’s intense security measures in the region. Furthermore, during this period, the state would begin articulating the alleged threat it faced within the Uyghur population as emanating first and foremost from certain aspects of Uyghur cultural and religious practices that the state would identify as ‘extremist.’ Happening in the backdrop of continued Chinese settler colonization of the Uyghur homeland, these efforts to target a threat within Uyghur culture would also serve to justify increased attempts by the PRC to forcibly assimilate Uyghurs into a Han-dominant Chinese culture that was taking over their homeland. Predictably, the Uyghur response to all of these measures would involve more violent resistance, continuing and escalating the self-perpetuating cycle of repression-violence-repression that had begun in the south in 2010.

SELF-FULFILLING PROPHECIES AND UYGHUR MILITANCIES

The concept of a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ has its origins in the work of Robert Merton, an American sociologist who began his scholarly career in the 1930s. Merton discusses the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ as originating in a false assessment about a social problem that leads to social or policy actions that make that false assessment a reality. Once this false assessment becomes a reality, it further justifies the actions that facilitated its existence. As Merton writes, ‘this specious validity of the self-fulfilling prophecy perpetuates a reign of error; for the prophet will cite the actual course of events as proof that he was right from the very beginning.’7

Merton’s examples of self-fulfilling prophecies are primarily related to structural racism in the US during the 1940s. He discusses, for example, how racist beliefs in the US that black people were intellectually ‘inferior’ to white people led to less investment in the education of the African American population. This lack of investment subsequently led to fewer black people enrolled in colleges, justifying further claims that they were intellectually inferior and not in need of increased investment in education.8 For Merton, the false assumptions that lead to such self-fulfilling prophecies are not innocent miscalculations or poorly formed policies. Rather, they are the product of deep-seated prejudices founded in a legacy of unequal power relations.

Merton’s formulation of this concept helps us understand how PRC policies against an imagined ‘terrorist threat’ would facilitate an increase in Uyghur militancy and perhaps even lead to a few actual ‘terrorist attacks’ carried out by Uyghurs by 2013–2014. In the PRC, and in its predecessor states in modern China, Uyghurs have always been subjected to structural racism that branded them as ‘inferior,’ ‘backward,’ and ‘volatile,’ serving to validate modern China’s paternalistic rule of colonial difference over them and its denial of their aspirations for self-determination in their homeland. However, when the PRC began characterizing all signs of Uyghur dissent and aspirations for self-determination as ‘terrorism’ in 2001, and had that characterization validated by the international recognition of ETIM as a ‘ terrorist organization’ in 2002, the nature of this structural racism intensified. These actions set in motion a process that effectively stripped Uyghurs of any legitimate grievances and gradually dehumanized them as an existential threat to state and society. As the state increasingly profiled Uyghurs as a threat, kept them under constant surveillance, and marginalized them in their own homeland, it was almost inevitable that the Uyghur response to these pressures would be violent rage. In turn, the PRC could point to the evidence of this rage to justify that it had been correct from the very beginning regarding the ‘terrorist threat’ posed by this population. In this sense, the SUV that crashed into Tiananmen Square in October 2013 was a response to the excesses of Chinese ‘counterterrorism’ measures, but it would also serve to justify these measures further.

ESCALATING VIOLENCE, COUNTERTERRORISM, AND COUNTER-EXTREMISM, 2013

Before the Uyghur family crashed its SUV into Tiananmen Square in October, the Uyghur homeland had already seen an increase during 2013 in the already existent cycle of violence and repression that had been ongoing in the region over the previous three years. While this cycle’s violence in 2013 included incidents in March in Korla and in May in Karghilik where Uyghur and Han citizens allegedly clashed for unclear reasons, other incidents had mostly consisted of violence between security organs and Uyghurs.9 These included an alleged gasoline bomb thrown at a police station in March and the alleged murder of two ‘community policemen,’ in April, both in Khotan.10 While almost all of these violent incidents in 2013 took place in the south of the Uyghur region, the most bloody of them took place in June in the town of Lukqun near Turpan in the north where a group of Uyghurs wielding machetes allegedly attacked a police station, local government buildings, and a construction site.11 In the end, the Uyghur attackers had allegedly killed 17 people, and all 10 purported attackers were killed by security forces.12 TIP issued a video praising the violence in Lukqun, which it framed again as an act of jihad, and calling Uyghurs inside the homeland to carry out more jihad operations.13 However, it remained unclear what had happened in Lukqun and whether it was politically motivated at all.

While the Chinese state media covered this incident given its magnitude, most of the violence in the Uyghur homeland during 2013 went unreported in official media, leaving much unexplained about the circumstances in which it took place. We only know of these violent incidents’ occurrence because citizens reported them on social media, and international journalists later confirmed them with local officials. However, there was one other violent incident aside from those near Turpan and in Tiananmen Square during 2013 that was reported on substantially by Chinese state media. This was the violence in Maralbeshi near Kashgar in April. State media reported that local police and ‘community workers’ had allegedly uncovered a ‘terrorist cell’ while conducting routine house-to-house searches in a rural area in Maralbeshi, leading to a clash that eventually ended in a house being burned to the ground and at least 15 police and ‘community workers’ killed.14 However, much about the event remains unclear. Some reports suggested that the Uyghurs responded violently when authorities found them watching a ‘terrorist’ video, and others said the group was merely conducting a Qur’anic study session at the time.15 Likewise, sources are unclear on how the house had burned down with police and ‘community workers’ inside and whether the fire was initiated by the Uyghurs or the police.16 The official media’s coverage of the event, which it reported as a ‘terrorist attack,’ was likely due to the large number of casualties suffered by security forces in the violence, but the coverage also gave the state an opportunity to ‘hype’ the threat posed by alleged ‘terrorists’ within the Uyghur population when TIP again issued a video commending the local Uyghurs involved and calling it an act of jihad.17

Whether or not directly linked to the violence in Lukqun and Maralbeshi, regional authorities at this time also began more earnestly seeking to link the growing violence in the region to religious ideologies they would label as ‘extremism.’ The PRC had generally linked religion to violent resistance in the region going back to the 1990 Baren incident, but this new effort went beyond seeking to punish those caught practicing religion outside state-mandated institutions to identify both the physical signs and cultural practices of those who might hold religious beliefs contrary to the state. According to one Chinese ‘counterterrorism expert,’ this effort was initiated by the regional Party’s issuance of an internal classified document in May 2013 called ‘Several Guiding Opinions on Further Suppressing Illegal Religious Activities and Combating the Infiltration of Religious Extremism in Accordance with Law,’ known colloquially as ‘Document No. 11.’18

The most vivid aspect of this new effort to identify what the state deemed to be ‘extremist’ within Uyghur cultural expressions was the ‘Project Beauty’ campaign during 2013 to alter Uyghur women’s clothing styles by forcing Uyghur women to adopt less modest dress and ‘show their beauty’ by disavowing veiling and clothing styles associated with women in the Muslim world. While ‘Project Beauty’ was a region-wide campaign, it was unevenly implemented and was particularly pronounced in the south of the Uyghur homeland. In Kashgar, checkpoints were instituted to police women’s facial coverings, and CCTV cameras were able to monitor women on the street for veils.19 Women caught wearing veils in public were written up by authorities and forced to participate in re-education by watching propaganda films advocating for women to show the ‘beauty of their faces’ in public.20

However, the state’s policing of dress and other markers of religiosity under the guise of combating ‘extremism’ would not be limited to public spaces. In the south around this time, authorities appear to have instituted more regular house-to-house searches to evaluate the behaviors of Uyghurs in private and to determine whether they met the state’s expectations of ‘extremism.’ Presumably, these expectations could be met by an evaluation of the religious books in a household, by dress and décor, and even by eating and drinking habits. Furthermore, these police searches were fortified by an army of Han cadres who were deployed throughout rural areas in the Uyghur region, particularly in the south. The Party had already announced this initiative in February 2013, calling for 200,000 cadres to deploy to 9,000 villages where they were expected to live and intermingle with the local population for at least a year.21 While these cadres claimed to be helping promote livelihoods in rural areas, they most definitely also played a role in policing behaviors, watching both local Uyghur administrators and monitoring the local population for signs of religious and cultural habits that the state had branded as ‘extremist.’22 It is probable that the ‘community workers’ killed in Maralbeshi were from this pool of cadres, and the violence there was likely sparked by the invasive nature of these ‘routine’ household searches.

Furthermore, this extensive monitoring of rural Uyghurs, especially in the south, would also include taking proactive actions against those seen as demonstrating traits deemed by the state to be ‘extremist.’ In particular, there were numerous incidents of massive state raids on observed gatherings of Uyghur men. The state would frequently characterize these raids as uncovering a ‘terrorist cell,’ but the fact that usually all of the Uyghur men targeted were killed left little evidence of what was actually transpiring. In August, for example, authorities near Karghilik killed 15 Uyghurs who were apparently surrounded while praying together in a desert location, and in Poskam county authorities killed at least 12 Uyghurs who were gathered in a rural area to allegedly ‘train’ in preparation for ‘terrorist acts.’23 Similar incidents around Kashgar and Yarkand reportedly killed 7 more Uyghurs in September and early October.24 In the aftermath of these incidents, local residents reported that their towns were virtually locked down and checkpoints were set up to check the identification of all local residents. While it was evident that TIP had nothing to do with these acts of local violence, which were mostly provoked by security forces, its Emir would issue another video in September, which urged the people of the region to continue what he characterized as their jihad against the Chinese state.25

Despite the significant violence which had already transpired in 2013 prior to the SUV crash in Tiananmen Square in late October, the incident in Beijing would predictably generate the most rapid response from authorities. Soon after this incident, a joint operation by Beijing and Xinjiang police arrested five Uyghurs in Khotan, who were accused of being part of an underground ‘terrorist’ group that had allegedly planned the car crash.26 Subsequently, their trial was covered in Chinese national media as a demonstration of the state’s capacity in ‘counterterrorism.’

However, the cycle of violence between Uyghurs and local security organs would continue in the south of the Uyghur homeland after October and into 2014. Two weeks after the incident in Tiananmen Square, nine Uyghur youth allegedly attacked a police station with axes and knives in Maralbeshi, bludgeoning to death two policemen.27 While the nine attackers were killed by police before authorities were able to interrogate them, state security portrayed this act of violence as yet another manifestation of internationally linked ‘terrorism.’ This further ensured that security sweeps would continue in the name of ‘counterterrorism’ through the rest of 2013, leading to more Uyghur arrests and deaths. In December, an alleged police ‘raid’ on another group of Uyghurs in Kashgar’s old city, whom authorities claimed were ‘terrorists,’ led to the killing of 16 Uyghurs, including 6 women.28 Like previous incidents that the authorities characterized as ‘raids’ and where Uyghurs were instantly killed, it was unclear what had actually happened. According to one Kashgar resident at the time, this was not a ‘raid,’ but a more mundane house search that had interrupted a planning meeting for an upcoming wedding. According to this account, violence between the members of the household and the police broke out when one officer attempted to lift a woman’s veil.29

It is difficult to know the full story behind any of the violence that took place in the Uyghur region during 2013 given the scant reliable details available about any of these incidents. Although it is possible, but unlikely, that some of the attacks may have been undertaken by aspiring jihadists and/or were inspired by access to TIP videos, it is clear that TIP itself had no direct involvement in any of the violence. As will be discussed below, TIP was likely too busy with other activities outside China in 2013 to carry out any attacks inside the country. Furthermore, most of these attacks did not look to be acts of ‘terrorism’ in the context of this book’s definition of that term. With the exception of the SUV crash in Tiananmen Square, the nature of which was debatable, all the violence targeted police and security organs rather than innocent civilians, fueling an ongoing conflict between Uyghurs, mostly from rural villages in the south of their homeland, and Chinese security services, which would continue into 2014

THE TURNING POINT: MARCH–MAY, 2014

The first months of 2014 appeared to represent a lull in the violence that had been occurring throughout 2013 in the south of the Uyghur homeland. Although it is likely that low-level incidents of violence continued, there were no reports of major events. However, in March of that year, a significant incident did occur, again taking place outside the Uyghur region. On 1 March 2014, a group of Uyghurs appeared to have indiscriminately attacked Han civilians with long knives inside the Kunming train station in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan. According to reports, 8 attackers, including 2 women, wearing all-black outfits killed 31 people, injuring an additional 141.30 The attack was on helpless civilians, appeared to be premeditated, and seemed to be politically motivated given that authorities allegedly found Eastern Turkistan flags at the scene of the crime.31 As such, it was the first time since the 1997 bus bombings in Urumqi that a Uyghur-perpetrated violent act reliably appeared to be a ‘terrorist attack’ by the definition adopted in this book.

Expectedly, TIP released a video praising the attack and calling it an act of jihad, using the event to further threaten Chinese officials about their policies in the Uyghur homeland, but, as had been the case previously, it did not directly claim credit for the attack.32 While this appeared to be a ‘terrorist attack’ by the working definition used here, it was not typical of those generally associated with international Islamic ‘extremist’ groups. In fact, there is no evidence that it was an act undertaken by a larger organization or that the attackers had the support of groups outside China. Rather, the attackers appeared to be acting on their own and responding to their particular situation.

According to state officials, the group had tried to leave the country through Southeast Asia to join the ‘global jihad’ but were unable to do so due to increased border security in the region.33 A report by RFA also suggested that the attackers were trying to leave the country via Southeast Asia, but not necessarily for the purposes of joining a ‘global jihad,’ and they were subsequently stuck in Kunming without any residency documents.34 In either scenario, it seemed clear that the attack was home-grown rather than ordered from outside the country, and the attackers were likely already on the run from police after attempting to leave the country when they decided to commit the violence.

Regardless of whether the attackers were responding to their precarious situation in Kunming, trying to make a political statement, or both, the impact of the incident on Chinese society was certainly akin to that of a ‘terrorist attack,’ inciting substantial fear. In this context, Han Islamophobic fear of Uyghurs in the country increased significantly, especially since the incident had occurred only five months after the SUV crash in Beijing. If the events around the Beijing Olympics and the Urumqi riots had already racially profiled Uyghurs as a ‘dangerous’ population, the Kunming attack led many to see that danger in the context of GWOT as an existential ‘terrorist threat,’ which was considered to be irrational, animalistic, and could strike anywhere and at any time, especially now that it was no longer contained in the Uyghur homeland. State officials also responded passionately and aggressively to the violence in the Kunming train station, marking a departure from the practice of not commenting on most Uyghur-perpetrated violence in the preceding two years. As Xi Jinping would announce to security officials almost immediately after the attack, you must ‘severely punish in accordance with the law the violent terrorists and resolutely crack down on those who have been swollen with arrogance … go all out to maintain social stability.’35

Xi’s concern about the incident prompted him to take his first trip as CCP General Secretary to the Uyghur region in late April, less than two months after the attack. During his trip, Xi was cited frequently in state media discussing counterterrorism efforts. He announced a ‘Strike First’ campaign to stop terrorists before they perpetrated violence and applauded the efforts of law enforcement and security agencies as the ‘fists and daggers’ in the battle against ‘terrorism.’36 As leaked documents have recently added, he called for this campaign to be an all-out ‘struggle against terrorism, infiltration and separatism’ using the ‘organs of dictatorship,’ and showing ‘absolutely no mercy.’37 It was in this context that, as Xi was ending his trip, it was reported that a Uyghur had set off an explosion in the Urumqi train station.38 In addition to the bomber, only one other person died, but 79 were injured. Xi Jinping was cited as telling local authorities after the attack to take ‘resolute measures’ and crush the ‘violent terrorists.’39

Like the incident in Kunming, the Urumqi bombing was an act of violence deliberately carried out against civilians, and its location again in a train station seemed to lend credence to the idea that there might be an organized group of Uyghurs who were developing a signature approach to carrying out ‘terrorist’ acts. TIP would once again add to such speculation by issuing a video about the attack, which mysteriously featured Abdul Häq, who had been assumed dead for the last four years.40 As is the case in most of TIP’s previous videos about incidents inside China, the group does not claim responsibility for the attack, but congratulates those jihadists in their homeland on their accomplishment. However, it does begin with a dramatization of how to make a suitcase bomb and then shows CCTV footage from the train station of the actual bomber detonating his bomb, leading some western ‘terrorism’ experts to assume TIP had orchestrated the attack.41 The video also called on believers in the homeland to continue their jihad, noting that it was always just to kill any Chinese civilian since they were infidels occupying a land that belonged to Muslims.42

Although this attack took place in Urumqi, it would lead to an escalation of security activities once again in the south, whose Uyghurs authorities assumed were the source of all instability in the region. A week after the Urumqi attack, there were reports that police had shot dead a young Uyghur in Aksu who got into an altercation with a policeman.43 Additionally, a protest in Aksu over the authorities’ detention of women and school girls for wearing conservative headscarves turned violent on 20 May as police allegedly fired into the crowd, killing several Uyghurs.44 Subsequently, police carried out security sweeps throughout the city into the night, arresting over 100 Uyghurs for their participation in the protests.45

Two days after the disturbances in Aksu, another attack occurred in Urumqi, and it would take even more lives than the Kunming and Urumqi train station attacks combined. On 22 May 2014, a group of Uyghurs allegedly drove two SUVs through barricades at a morning market, which was almost exclusively frequented by Han in Urumqi and threw explosive devices as they ploughed through people on the street, with the vehicles eventually erupting into fire.46 While it was initially reported that 31 had died, with over 90 injured, by the next day, the death toll had risen to 43.47 The local authorities called the incident ‘a serious violent terrorist incident of a particularly vile nature,’ and they predictably had the city heavily patrolled in its aftermath.48 This was the third sensational attack against civilians in three months. In total, at least 98 violent incidents were reported involving Uyghurs and police or Han civilians inside China in 2013 and 2014, resulting in between 656 and 715 deaths.49 In response to this escalation in violence, the state was prepared to use an even heavier hand.

The week after the Urumqi market attack, Zhang Chunxian, the head of the CCP in the Uyghur region, announced the commencement of what he called the ‘People’s War on Terror.’50 While it was not surprising to hear a Han political leader from the region pledging to combat ‘terrorism’ in the wake of the violent attacks of the previous three months, Zhang’s framing of these efforts as a ‘People’s War’ suggested a populist response evocative of the country’s Maoist legacy. Indeed, this ‘People’s War on Terror’ was to be used as a brand describing a variety of state policies that were reminiscent of past attempts at mass indoctrination and intense social pressure from Maoist times.51 In his statement, Zhang also signaled that this ‘war’ would be first and foremost about ideology. As he said, the state must ‘promote the eradication of extremism, further expose and criticize the “reactionary nature” of the “three forces,” enhance schools’ capacity to resist ideological infiltration by religious extremism, and resolutely win the ideological battle against separation and infiltration.’ However, he also framed this ideological struggle in terms that evoked the growing influence of ‘Second Generation Nationalities Policy’ in the region, noting that ‘efforts should be made to make all ethnic groups in Xinjiang identify with the great motherland, the Chinese nation, the Chinese culture and the socialist path with Chinese characteristics.’52

However, it would be inaccurate to suggest that these policy shifts towards a more heavy-handed and ideological war against Uyghur dissent were the initiative of Zhang’s local administration alone. Rather, they probably had their foundations in the central apparatus of the Party, particularly through the preparations for the Second Xinjiang Work Forum, which took place only days after Zheng’s new declaration of a ‘People’s War on Terror’ and which would reinforce Zhang’s formulation of this war. Numerous observers have noted that the Second Xinjiang Work Forum marked a departure from previous state approaches to the problems of the Uyghur region and Uyghur dissent. First, this second Work Forum stepped back from the previous focus on development and emphasized the issue of ‘stability maintenance,’ mostly articulated through the prism of ‘counterterrorism,’ and second, it highlighted overtly assimilationist goals as a constituent part of maintaining this stability, reflecting an even stronger embrace of the ‘Second Generation Nationalities Policy’ than had the first Work Forum.53

This did not mean that development in the Uyghur region was no longer important to the PRC. To the contrary, the region’s development would become a major preoccupation of Xi Jinping in the coming years. Xi had unveiled his plans for an ambitious ‘Silk Road Economic Belt,’ the land-based portion of the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI), only a year earlier in Kazakhstan.54 It was clear that the implementation of this ‘Silk Road Economic Belt,’ which was part of Xi’s signature foreign policy project, would require following through with the grand development plans for the Uyghur homeland, which was envisioned as the entry/exit point for all of BRI’s transport infrastructure to the west and south-west. As Xi Jinping would state at the work forum, ‘Xinjiang work possesses a position of special strategic significance in the work of the Party and the state … the long-term stability of the autonomous region is vital to the whole country’s reform, development and stability.’55 If the development of the Uyghur region remained as critical, or more so, than previously to PRC objectives, the CCP had inverted its formerly declared relationship between development and stability. Development would no longer necessarily bring stability, but stability was now necessary for development, which was needed for the advancement of the PRC as a whole.

Finally, stability was now increasingly premised on a strategy of dismantling Uyghur identity, especially its Islamic aspects, and assimilating Uyghurs into a broader national identity in the name of combating ‘terrorism.’56 Setting the tone for these new assimilationist approaches to establishing and maintaining stability, Xi echoed Zhang’s earlier assertion that it was critical for all residents of the region, regardless of ethnicity, to identify with China, the Chinese nation, its culture, and its form of socialism.57 Xi further noted that it was critical to ‘strengthen inter-ethnic contact, exchange and mingling’ and to ensure that the people of the region became ‘tightly bound together like the seeds of a pomegranate.’58 By couching this new focus on assimilation in the context of ‘counterterrorism,’ the PRC was able to use the alleged threat of ‘extremism’ as its justification and point to ‘de-radicalization’ programs in the west as an analogy. Given the subjective nature of the label of ‘extremism,’ this gave the state a justification for attacking virtually all Muslim religious practices, many of which had become part and parcel of Uyghur identity. As such, this Second Xinjiang Work Forum was very definitely setting the stage for the Uyghur cultural genocide that was on the horizon.

THE ‘PEOPLE’S WAR ON TERROR,’ 2014–2016

The ‘People’s War on Terror,’ as implemented through 2016, involved a multi-pronged attempt to cleanse Uyghurs of Islamic influences while simultaneously trying to instill in them a new form of PRC nationalism. It would, predictably, include a concerted effort to weed out and violently punish those believed to be ‘extremists’ and ‘terrorists,’ but it also involved wider efforts to alter Uyghur social behavior and cultural practices. This included further implementing the ‘Project Beauty’ campaign among both women and men in order to restrict the wearing of Islamic-styled clothes and facial hair, an intensification of anti-religious education, attempts to prevent Uyghurs from engaging in religious practices, and the enlistment of all citizens in a campaign to regulate each other. Furthermore, it would lay the foundations for the sophisticated surveillance system that would monitor compliance with these efforts. Overall, it was a much more culturally focused attempt to address Uyghur dissent in the region than had been adopted in the past, but it also was assimilationist in its approach, and, for pious Uyghurs, exclusionary in its practice.

This ideological campaign to address ‘extremism’ was itself very extreme from the start. In schools, students were actively discouraged from adopting religiosity in any form, and were encouraged to report on religious behavior among their parents. Public ‘anti-extremism’ campaigns led to frequent attempts to prevent Uyghurs from fasting during Ramadan, to promote the drinking of alcohol and the smoking of cigarettes, suggesting that abstinence from these habits was a manifestation of extremism, and to increase surveillance of mosque attendance and the religious aspects of traditional Uyghur life-cycle rituals.59 The campaign also included attempts to mobilize Uyghur communities to help the state in policing the population for signs of religiosity. Authorities encouraged community members to report on those amongst them who publicly displayed signs of religiosity, in some cases even providing substantial monetary rewards for such reports.60 Contests were begun throughout the region for the best ‘anti-terrorism’ and ‘anti-extremism’ murals, which became ubiquitous as anti-religious propaganda in public spaces, especially in the south.61 In other instances, locals were trained in how to attack ‘terrorists’ they encountered with farm tools and were encouraged to join ‘volunteer’ militia to assist the police in weeding out alleged ‘terrorists.’62 Furthermore, some local administrations in the Uyghur homeland were particularly transparent with regards to the role that miscegenation could play in its efforts to change Uyghur behaviors, offering substantial monetary incentives to promote inter-marriage between Han and Uyghurs.63

While many of the extreme manifestations of this ideological war appeared to differ by region within the Uyghur homeland, they were not limited to rural and religious Uyghurs in the south. The campaign also targeted Uyghur intellectuals and nationalists who were not religious and not necessarily from the south of the Uyghur homeland. As evidence of this, authorities in the Uyghur region began policing the Uyghur-language internet, with even more scrutiny than before, for any content that suggested criticism of the CCP particularly targeting content that was either religious or nationalist in nature.64 The most sensational example of this increased internet scrutiny was the arrest of Ilham Tohti, a Uyghur economics professor living in Beijing, on charges of promoting ‘separatism.’ Tohti likely had been the only Uyghur public intellectual able to openly criticize state policies in the Uyghur region given his residency in Beijing, but he was not a proponent of Uyghur independence from the PRC. He was well-respected among Han intellectuals, and his writings were focused on promoting the integration of Uyghurs and their homeland into the PRC, albeit on their own terms that recognized their historical relationship with their homeland.65 However, he had created an internet forum about Uyghurs and their homeland that encouraged frank and honest discussion between Uyghurs and Han of conditions in the region. In September 2014, Tohti was convicted of ‘separatism,’ presumably on the basis of this internet forum, and given a life sentence in prison, a much harsher punishment than that usually given to prominent Han dissidents.66 This event sent a message to all Uyghurs that the Chinese state would now tolerate no objections to or open debate about its policies and that the terms of the ‘People’s War on Terror’ that had been set by the state were non-negotiable.

About a year after Tohti’s sentencing, the PRC also passed a new ‘Counterterrorism Law’ in 2015, which would codify many of the anti-Islamic and assimilationist policies already being implemented in parts of the Uyghur homeland as a means of combating ‘extremism.’ With these policies now stipulated by law, it was no longer Uyghurs in specific regions who were subjected to such actions, but all Uyghurs. According to the law, ‘terrorism’ ‘refers to propositions and actions that create social panic, endanger public safety, violate person and property, or coerce national organs or international organizations, through methods such as violence, destruction, intimidation, so as to achieve their political, ideological, or other objectives.’67 The inclusion of ‘propositions’ and ‘intimidation’ in this definition allowed for a broad understanding of the concept, which was not limited to acts of violence, and potentially included any independent political act seeking to persuade others.

Furthermore, articles 80 and 81 of the law prohibit a variety of ‘extremist activities,’ most of which are completely subjective. These include the extremely vague action of ‘using methods such as intimidation or harassment to interfere in the habits and ways of life of other persons,’ as well as a number of activities regarding the promotion of religion writ large and actions meant to discourage people from living or interacting with those of other ethnic groups and faiths.68 As the international coverage of this new law pointed out, these articles particularly targeted parents for actions they might take in the course of parenting their children, effectively seeking to drive a wedge between the older and younger generation of Uyghurs.69

This law was further reinforced in the Uyghur homeland by the initiation of new ‘Religious Affairs Regulations’ that were intended to distinguish between legal and illegal expressions of Islam. These regulations were likely instituted as a means to codify many of the anti-religion policies being undertaken in the region, but they remained extremely vague and highly subjective, especially with regards to the definition of ‘extremist’ activities and attire, both of which were prohibited. Article 38, for example, prohibited people from adopting an ‘appearance [i.e. grooming], clothing and personal adornment, symbols, and other markings to whip up religious fanaticism, disseminate religious extremist ideologies, or coerce or force others to wear extremist clothing, religious extremist symbols, or other markings.’70 However, it was not clear at all what constituted ‘extremist’ ideologies, clothing, symbols, or markings.

Both the ‘Religious Affairs Regulations’ and the ‘Counterterrorism Law’ led to a far more concerted effort than previously to pursue the ideological struggle against ‘terrorism’ (as that term was understood by the Party) that had been promised by the ‘People’s War.’ In many ways, the stipulations in these legal documents had already been in effect prior to 2015 in the region, especially in the south. As one journalist would state in a report from Kashgar in 2014, it appeared that China was waging ‘an all-out attack on Islam’ in the region.71 However, the new legal guidance ensured that this attack on Islam would become more systematic and extend far beyond Kashgar.

In addition to its ideological focus, the ‘People’s War’ increased the violent policing of Uyghurs by security organs that had been steadily escalating since 2011. Almost immediately after its declaration, authorities held a public execution of 55 alleged Uyghur ‘terrorists’ in the town of Ghulja, and security organs conducted a massive ‘counterterrorism’ sweep in the region, which detained over 200 Uyghurs for alleged ‘terrorist activities.’72 By the end of 2014, it was reported that the number of arrests in the Uyghur region had nearly doubled from the previous year, largely reflective of increased detentions on vaguely defined ‘terrorism’ related charges.73 In the southern rural areas of the Uyghur region, local security organs were tasked with even more regular house-to-house inspections to monitor dissident behavior, and targeted people in these communities were virtually held under house arrest.74 As one might expect from past experience, this intensification in the monitoring of Uyghurs by security forces only spawned more violent resistance from Uyghurs, subsequently only further escalating the ongoing conflict between Uyghurs and security organs, especially in the south of the Uyghur region.

Violent incidents, whether initiated by security forces or Uyghurs, quickly increased even more after May 2014, and virtually all of them occurred in the south of the Uyghur homeland. A significant number of the violent incidents were provoked by house-to-house inspections and police ‘raids,’ as had been the case in the previous year.75 Others were Uyghur attacks on police and government officials or on police stations and government buildings.76 The violence began appearing increasingly political again in July and August of 2014, resulting in assassinations of five judicial officials in Aksu and of the Imam of Kashgar’s main mosque, who had been a vocal supporter of the state’s ‘counterterrorism’ measures in local media.77

However, the most brutal violence of 2014 would take place under a shroud of mystery in a village near Yarkand called Elishqu in late July. State accounts claimed that this was a mass ‘terrorist’ attack on a police station, while Uyghur sources asserted that it was the result of the repression of a protest in response to restrictions on Uyghurs’ ability to observe Ramadan and to the police killings of Uyghurs during house-to-house searches.78 According to state sources, 96 people had died in the violence, including 59 alleged ‘terrorists,’ but the WUC would claim that as many as 2000 Uyghurs had been killed.79 Independent journalist accounts suggest that the violence began as authorities raided what they considered an ‘illegal religious gathering,’ which could have been any gathering of Uyghur men.80 Regardless of what happened, and who the main aggressors were, the incident had obviously turned into a massacre, traumatizing the local population. Follow-up trips by international journalists to the region to find out what had actually happened were unsuccessful, but they did suggest that the area had been put under complete lockdown, even two years later.81 In the aftermath of the incident, the CCP leader in the Uyghur region, Zhang Chunxian, responded by making clear that state efforts would only become more intense. As he noted, ‘We have to hit hard, hit accurately and hit with awe-inspiring force … to fight such evils we must aim at extermination … to cut weeds we must dig out the roots.’82

There was a similar flow of violent incidents in 2015 as in 2014. Much of this violence followed the pattern of resistance to security inspections that had occurred throughout 2013 and 2014, but it now also involved numerous clashes at the checkpoints that had become common throughout the region.83 This included three alleged suicide attacks on such inspection posts near Khotan in the towns of Lop and Karakash in May and one particularly deadly one in Kashgar in June.84 The incident that would be the most violent in 2015 occurred in September near Aksu where Uyghurs had allegedly killed 50 some Han coal miners while they slept in their dormitories.85 However, like most of the Uyghur-perpetrated violence inside China, the details of this incident were unknown. While state media in China did not report the mine attack for almost two months, when it did, it again suggested that this was the work of a ‘terrorist’ group linked to international jihadist networks.86 Uyghurs from the region have told me that the incident was actually related to local land disputes. Regardless of the motivations, the security forces killed on the spot 28 Uyghurs whom they claimed had committed the act, without bothering to even arrest them.87 Authorities also allegedly arrested at least two other Uyghurs accused of being involved in the incident, and state media publicly aired nationally an interview with one of them, who claimed that the killings were undertaken as an act of jihad.88

As a result of this intensification of violence in the southern Tarim Basin during 2014–2015, securitization in the region predictably only intensified. By 2016, there were reports that many Uyghur neighborhoods in urban areas had been fenced off from the rest of the city and were surveilled by an increased police presence as well as more numerous CCTV cameras.89 The call to prayer was also outlawed, Uyghurs were subjected to more limits on their ability to move within their own homeland, and the state even outlawed a list of children’s names that have Arabic roots and religious significance.90 According to Zhang Chunxian, the head of the CCP in the region, these measures had greatly reduced violence in the region by March 2016, but it is likely that low-level violence continued unreported.91

While a few Uyghur elites living in Urumqi at this time have told me that they were prospering in this context, for most Uyghurs, especially those from rural villages, the pressure from security organs in the region was reaching a peak by the summer of 2016. As Darren Byler has noted from his research among rural migrants to Urumqi, this pressure, which included almost nightly checks on households, had completely alienated rural Uyghurs and had left substantial psychological scars on them.92 Furthermore, the close scrutiny of residency permits at this time was serving to keep rural Uyghurs out of urban areas and to essentially quarantine them in tightly controlled rural villages.93 This pressure had been building in southern rural regions of the Uyghur homeland since 2010, spurring much of the violence described above. However, some rural Uyghurs found another way to respond to this pressure; they abandoned their homeland entirely.

EXODUS FROM THE HOMELAND

While there are no official statistics on how many Uyghurs left China between 2010 and 2016, it was certainly in the tens of thousands and likely at least 30,000. As such, it would ultimately become the largest exodus of Uyghurs from China since May 1962 when some 60,000 Uyghurs had reportedly fled to Soviet Kazakhstan. However, the exodus between 2010 and 2016 would not take place over the course of days and involve a mass transfer of population over a single border as was the case in 1962. Instead, it would happen over the course of years and involve a series of different methods of travel and multiple borders. It would also involve both illegal and legal means of leaving China.

For most Uyghurs, since at least 2006 it has been extremely difficult to obtain passports for international travel, and it had become almost impossible for all but a small minority of Uyghurs after 2009.94 Furthermore, for those who had passports, a practice was instituted that required them to be housed with either state travel agencies or local police, ostensibly forcing their holders to request state permission to leave the country.95 In this situation, many Uyghurs, especially from rural regions in the south, began using human trafficking routes through Southeast Asia to flee illegally without documentation. While these routes were relatively well-established, they were largely new to Uyghurs, who had traditionally fled China via the borders of their homeland to locations in Central and South Asia. However, after the 2009 Urumqi riots, routes out of China through Southeast Asia would begin to see significant Uyghur traffic. In December 2009, Cambodia detained 18 Uyghurs, including women and children, who had apparently fled the PRC. Cambodia extradited the group back to China, and, upon their arrival, the adults amongst them were arrested, with two of them receiving life sentences.96 Similarly, Laos extradited 7 Uyghurs in March 2010.97 In 2011–2012, Malaysia also extradited a total of 17 Uyghurs, who were in the country without proper documents.98 While these extraditions drew criticism from human rights groups, the international community had no idea of the extent of the exodus of Uyghurs that was transiting Southeast Asia until 2014 when Thai authorities arrested 424 Uyghur men, women, and children, some 200 of which were hiding in a single trafficking camp in Songkhla province.99 The Uyghurs claimed to have Turkish citizenship, and Thailand was caught in a diplomatic battle between China and Turkey for the right to have these refugees sent to their country. While Thailand did send approximately 170 of the refugees, almost exclusively women and children, to Turkey, 109 men were extradited to China in July 2015.100

However, even this large number of refugees detained in Thailand represented a small fraction of the number of Uyghurs who likely used these human trafficking routes between 2010 and 2014 to leave China. Most Uyghurs leaving China via Southeast Asia intended to make their way to Turkey where it was known that they could receive refuge, but they also did not necessarily have a plan regarding how to do so. Uyghur activists in Turkey with whom I have spoken played an important role in facilitating the final stage of the journey from Southeast Asia to Turkey, negotiating with multiple governments in the process. While exact numbers of Uyghurs who left China through Southeast Asia between 2010 and 2014 may never be known, these activists claimed to have successfully transferred some 10,000 Uyghurs from Malaysia and Thailand to Turkey between 2012 and 2016. Others remain in detention centers in Malaysia and Thailand at the time of this book’s publication, and some undoubtedly remain in these countries as undocumented immigrants.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that most of these refugees had come from the southern oases of the Uyghur homeland and primarily from rural villages. When I conducted interviews in the Turkish city of Kayseri during the summer of 2016 with Uyghurs who had fled China via Southeast Asia, all of those I met had come from the villages around Kashgar, Khotan, Yarkand, and Aksu. They mentioned that the pressure from police had been the primary factor which solidified their decision to leave, citing constant household inspections and harassment. Some also attributed their decision to flee as further motivated by their inability to peacefully practice Islam and their children’s mandatory education in Chinese-language schools. These motivations for the exodus correspond with the findings of a report by the WUC, which also conducted interviews in Turkey with refugees who had fled China via Southeast Asia at this time.101 The WUC also notes that most of the Uyghur men among the refugee families had spent time in PRC prisons and had been subsequently targeted for particular surveillance by authorities on their release.102

It is noteworthy that many fled with their entire families, including large numbers of children. They described a harrowing journey that brought them from the Yunnan and Guanxi Provinces of China across various borders with Laos, Vietnam, and Burma.103 Those with whom I spoke told heartbreaking stories of the members of their groups who had died from illness or accident along the road and spoke about the difficult conditions while in the hands of traffickers.

Much remains mysterious about this mass exodus of Uyghurs through Southeast Asia. Interviewees told the WUC a variety of stories, which suggested that information about this ‘underground railroad’ out of China had spread via word of mouth and had likely included numerous human trafficking rings. Most of my interviewees suggested that they had learned about the opportunity to flee from friends and family, but two told me that Han traffickers had come directly to their village to ask them if they wanted to leave the country. The Chinese government never recognized the scale of the exodus, but it did finally acknowledge that it was occurring, suggesting that it was a human trafficking ring founded by Islamic ‘extremists’ to bring Uyghurs to fight in the global jihad. Chinese authorities made claims about this alleged jihadist smuggling ring in relation both to the Kunming train station attack in March 2014 and to the December 2014 incident where authorities arrested 21 Uyghurs and killed one for trying to cross the border in Guanxi province.104 The Chinese state again made the same claims about the 109 Uyghur men returned to China from Thailand in 2015.105

It is important to note that none of the Uyghur refugees I interviewed in Turkey claimed that they had left China to join militant groups, and even ‘terrorism’ experts following ETIM/TIP are skeptical of this narrative.106 However, it is evident that some of these refugees were eventually recruited by jihadist groups that were able to offer them refuge. A small number somehow came to be entangled with groups in Indonesia, including the Mujahidin Indonesia Timur, but the majority were recruited by TIP, which was preparing for its operations in Syria.107 According to Uyghur activists who had gone to both Malaysia and Thailand to help refugees there get to Turkey, they encountered another Turkish Uyghur in Southeast Asia who was actively recruiting for TIP. It is unclear how many Uyghurs this person was able to recruit, but he likely had established an alternative route for some refugees to get to Turkey before directly moving on to Syria.

The PRC appears to have halted the flow of Uyghur refugees to Southeast Asia by late 2014, but Uyghurs were still apparently finding ways to flee the country. In November 2014, the PRC claimed to have broken up a Turkish-led ring providing Uyghurs with fake passports, once again claiming that the purpose of the operation was to send Uyghurs to join the global jihad.108 Having resulted in the arrest of ten Turkish citizens, this incident created tension in the Turkish-Chinese diplomatic relationship, with the PRC claiming that Turkey was helping Uyghurs join ‘terrorist’ groups. Regardless of the actual story behind this alleged system of fake passport distribution, after this incident, it appears that most illegal routes out of China for Uyghurs, including via forged passports, had been neutralized.

Fortunately for Uyghurs, local Chinese authorities began implementing an unusual policy in August 2015, allowing all Uyghurs whose passports had been held by the state to freely get them back and encouraging others without existing passports to apply for them. Predictably, many Uyghurs took this opportunity to retrieve their existing passports or apply for new ones and leave the country legally, mostly traveling to Turkey. As a result, a significant influx of Uyghurs arrived in Turkey legally via airplane in late 2015, adding to the Uyghur diaspora population in Turkey much more than those who had arrived via Southeast Asia trafficking routes. This policy, which was uncharacteristically accommodationist, seemed to be ordered by Zhang Chuxian himself just months before he was replaced. It is unclear why Zhang would want to give Uyghurs their passports back in 2015, and the decision was not accompanied by a long and transparent paper trail that could provide clues about the policy’s purpose.

However, one can speculate about possible motivations. Chinese authorities remained concerned about the potential for violent resistance to Chinese rule in the Uyghur region, and Zhang may have decided that letting dissatisfied Uyghurs leave on their own accord would help prevent future violence through a policy of ‘voluntary’ ethnic cleansing of territory by those deemed by the state to be infected with the ‘three evils.’ However, it may have also been merely an early attempt to compile data on the Uyghur population to assist in their surveillance. Residents of the Uyghur region were subjected to a far more rigorous passport application process than other Chinese citizens, requiring extensive bio-data, including voice samples, DNA collection, and a 3D image of themselves.109 Regardless of the motivations, this policy led to the departure of thousands of additional Uyghurs during the months it was in effect. By late October 2016, the policy was once again reversed as Uyghurs’ passports were gradually and systematically again confiscated by the police.110

As already noted briefly, a substantial number of these new Uyghur refugees in Turkey would mysteriously end up in Syria fighting with TIP, which also suddenly had a substantial and well-equipped army for the first time in its history. This was yet another aspect of the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ of China’s efforts since 2001 to assert that it faced a serious ‘terrorist threat’ from within its Uyghur population. However, it is noteworthy that this new incarnation of TIP in Syria was not necessarily the same organization with the same allegiances as had been the case in Pakistan only a few years prior.

TIP IN SYRIA

Oh Turkistan, we have not forgotten you

We swore to free you

We have marched forth to achieve this great goal

We were once oppressed and humiliated under the disbelievers

Look now, we have all sorts of weapons in our hands

Marching forth in the battles with pride and seeking martyrdom

We are the ones who pledged to die in the path of Allah

TIP, Jihad Otida/Love of Jihad (October 2018)

In October 2012, the Chinese state media first claimed that Uyghurs were heading to Syria to join ‘terrorist organizations,’ asserting that both ETIM and a Turkey-based group, the Eastern Turkistan Education and Solidarity Association (ETESA), were working together to bring Uyghurs into Syria.111 In July 2013, the Chinese government also claimed that they had apprehended one Uyghur coming back to the country after having fought in Syria.112 While it was not surprising that some Uyghurs would end up in the ranks of foreign fighters in Syria, most observers at the time assumed that the number of Uyghurs doing so was very small.113 However, by 2014, TIP was making videos inside Syria, showing a larger and better equipped army than it ever had in Afghanistan or Pakistan as well as pictures of a community that included many children.114 A year later, in 2015, it was known that TIP had an active army in Syria that had contributed to numerous battles in the north of the country, including critical ones in Jisr Al-Shughur, at the Al-Duhur Military Airbase, and in Qarqur.115 It was also at this time that information began spreading about TIP having established what essentially amounted to Uyghur settlements in northern Syria near the border with Turkey comprising communities of entire families.116 How had TIP gone from a small shell organization of Al-Qaeda engaged mostly in propaganda in the Pakistan-Afghanistan frontier to a large fighting force and settlement in Syria in a matter of three years?

Al-Qaeda and Turkey: strange bedfellows in TIP’s emergence in Syria?

Much of the story about how TIP became established in Syria so quickly given its former lack of capacity and resources remains shrouded in mystery. However, it does seem clear that assistance from, and perhaps manipulation by, both Al-Qaeda and Turkey were contributing factors. As TIP already appeared to be gaining more recruits in Waziristan in 2011, it had also become more ideologically integrated into Al-Qaeda. When the former Emir Abdushukur was killed by a drone strike in 2012, only Abdullah Mansur and Abdul Häq, who had yet to reappear from his alleged killing, remained from the original organizers of TIP during the 2008 Olympics. Given that the organization was suddenly gaining significant numbers of new fighters, perhaps for the first time ever, it is likely that Al-Qaeda took notice of the group’s potential and took greater control over the organization’s leadership, which had significantly dwindled.

If this is true, it is likely that TIP began getting involved in Syria as early as 2012, at the same time that Al-Qaeda entered the country’s civil war. Al-Qaeda first became active in Syria with the establishment of the Al-Nusra Front to Protect the Levant in January 2012.117 By March 2013, TIP was suggesting in its Arabic-language magazine that it was already represented among the foreign fighters in Syria.118 I have also met at least one Uyghur who was already in Syria in 2013 with TIP. He had come to the country via Turkey and had joined a small group of TIP recruits to partake in some military training and establish operations in the country. He also noted that a smaller group of Uyghurs was with Daesh at this time, which had yet to completely split with Al-Qaeda. Given the video produced in 2014 of Uyghur fighters in Syria, it would appear that the group was already fairly well established by this time and was working with Arab jihadist groups, likely linked to Al-Nursra.

However, it is not until 2015 that we see clear evidence of a larger TIP fighting force in the country through videos documenting their participation in key battles near Idlib.119 TIP also made numerous recruiting videos at this time, suggesting that its numbers were continuing to grow. These videos show that TIP sought to appeal to a variety of emotions and different populations in recruiting people to come to Syria. A significant number of the recruitment videos focus on the plight of Uyghurs in China, connecting it to the struggle of Muslims globally, and stressing how joining the jihad in Syria will prepare Uyghurs to fight China.120 Others appealed to potential Uyghur recruits by showing the strong and loving community of Uyghurs in Syria, including the many children who had come to the country with their parents.121 However, it is also telling that TIP had transitioned to recruiting non-Uyghurs as well at this time, making videos in Turkish, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz languages in addition to those in Uyghur.122

If Al-Qaeda and the aligned Al-Nursra helped get TIP established in northern Syria, there is also plenty of anecdotal evidence of Turkish involvement in helping to funnel Uyghur refugees to join the group there. As has already been noted, an overwhelming number of Uyghur refugees, perhaps numbering as many as 30,000, arrived in Turkey around this time both via human trafficking networks through Southeast Asia and more directly and legally with passports given out to Uyghurs in China in 2015–2016. On arrival, Turkey provided them with neither official refugee status nor full citizenship. Rather, they were generally given temporary residency permits, usually without the right to work, and, at the time of this book’s publication, many remained in the country under such tenuous status. While Turkey, with perhaps a few recent exceptions, has not extradited these Uyghur refugees to China, their situation in the country is tenuous at best, and they have struggled to make ends meet, especially those who have not even been afforded work permits. The uncertainty of their immigration status and their economic situation provided incentives for many among these Uyghur refugees in Turkey to go to Syria where they were promised housing, food, and schools for their children.

While a small number of the Uyghurs in Syria may already have been recruited by TIP in Southeast Asia, it appears the majority came after they had already found refuge in Turkey. From my discussions with Uyghur activists in Turkey who have tried to accommodate the many refugees arriving from their homeland in recent years, it is clear that they have needed to contend with another group of Uyghurs in Turkey who are funneling these new arrivals to join TIP in Syria. One of the few journalistic pieces to examine this question, for example, recounts one activist who encountered such TIP recruiters when he was meeting a group of refugees at Istanbul airport in 2015 with the intent of bringing them to the city.123 Instead, these recruiters ushered the newcomers onto buses headed directly to Syria.

More often, these refugees were enticed to come to Syria after already struggling to make ends meet in Turkey. One TIP recruiter identified by my interviewees who had gone from Turkey to join TIP in Syria was a man by the name of Säyfullah, who appeared to be based in Istanbul. He told many recruits that joining TIP in Syria would be training for the group’s eventual plan to wage a war of liberation in Eastern Turkistan. Activists seeking to prevent Uyghurs from going to Syria have also discussed being harassed and pressured to stop their work by thugs assumed to be serving TIP.124 However, it remains unclear whether these recruiters and thugs are working for Al-Qaeda, for TIP in Pakistan/Afghanistan, for Turkish supporters of TIP, or for somebody else entirely. The Chinese government has also accused the Turkey-based Uyghur organization ETESA (known by Uyghurs as Maarip) of being involved in recruitment, but this organization has instead played an active role in discouraging Uyghurs from going to Syria. There has been some speculation that the Turkish government itself supported Uyghur refugee recruitment into TIP, but no conclusive evidence of this exists. Much of this speculation comes from partisan Middle Eastern sources, which have suggested that the Uyghur settlements in Syria are a part either of a Turkish ‘colonization’ of northern Syria or of a Turkish-supported plot to promote ‘insurgency in Xinjiang.’125 Despite the questionable nature of these sources and many of their suspect arguments, their assertions of state involvement are not entirely far-fetched. It has been well documented that Turkey allowed a variety of jihadist groups and their weapons to transit the country on their way to Syria, and Turkey, at least in the early years of the war, was somewhat supportive of Al-Nusra, which shared common enemies with the Turkey-backed Free Syrian Army.126 Additionally, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that Uyghurs involved with TIP have been able to move freely back and forth over the Syrian border with little to no resistance from Turkish border guards.

Who are the Uyghur jihadists of TIP?

The number of Uyghurs who have joined TIP in their battles in Syria is unknown, but it is substantial. The alleged high-level member of TIP I met in Turkey during the summer of 2019 suggested that the group represented 30,000 Uyghurs inside Syria at its peak. The Syrian ambassador to China claimed in 2017 that the number of Uyghur foreign fighters in Syria was around 5,000.127 By contrast, Israeli intelligence at the same time published a report suggesting that TIP had 3,000 Uyghur fighters in Syria.128 It is important to note that the Uyghurs in Syria include substantial numbers of families where only the adult males would serve as actual fighters for TIP. Thus, the number of Uyghurs in Syria may be much larger than the number of TIP fighters in the country. However, unlike Daesh, TIP does not appear to keep reliable records of their membership, and, thus, its true number in Syria is unlikely ever to be known.

Furthermore, like Häsän Mäkhsum’s group in Afghanistan and Abdul Häq’s TIP in Pakistan, TIP in Syria appears to operate more like a community than a militant organization. While those from the community who participate in warfare, primarily the adult men, obviously follow a chain of command and answer to superiors, the community of TIP in the country appears much more loosely organized and independent of larger jihadist groups. People travel back and forth between the community in Syria and the Uyghur community in Turkey. They have created what amount to Uyghur villages in Syria, complete with schools, but there is little evidence that these villages live under the command of any particular individual or group. Finally, it is not even clear that those who have joined this community at different times or even participated in battles consider themselves ‘members’ of TIP.

Mohanad Ali Hage of the Carnegie Middle East Center, who has interviewed people in the region of Idlib where TIP has been most active, calls the Uyghurs with TIP in Syria ‘a different type of jihadi.’129 He notes that they do not appear interested in ruling over civilian populations, collecting taxes, or enforcing Sharia Law; rather, they tend to settle in abandoned towns where they keep to themselves and focus their fighting against Assad’s armies and their allies.130 Those Uyghurs I have interviewed who have been with TIP in Syria provide similar descriptions. They talk about towns and neighborhoods completely inhabited by Uyghurs with schools that teach Islam, mathematics, and a variety of other subjects.131 While TIP videos suggest that the schools also train students in the use of weapons and the art of warfare, there is no evidence that TIP operations use child soldiers. Furthermore, TIP videos also highlight the communal nature of life for Uyghurs in Syria, showing holiday celebrations and other community gatherings in addition to the battles in which men are involved.

In this context, one can understand some of the attraction of Syria to Uyghur refugees. It offers a life lived on their own terms and by their own rules. While the rules by which this community lives are conservative, it is notable that my informants who had been part of the community suggest that they were not aggressively ruled by Sharia law. They mention, for example, being lectured by non-Uyghur jihadists about their lackadaisical approach to praying five times a day and their propensity for smoking cigarettes, both behavior that was tolerated in TIP’s own community. That said, it is notable that few if any TIP videos show Uyghur women in Syria, suggesting a highly sex-segregated society.

A full account of the Uyghur community associated with TIP in Syria would be difficult to reconstruct with the fragmented information available to us. That said, one can piece together a few different types of Uyghurs who have joined TIP in Syria. All of the Uyghurs I have interviewed who have had experience with TIP in Syria have told me unequivocally that their motivation for going to Syria was to gain combat experience that would eventually be used in a war to liberate their homeland from the PRC. They have generally been in their twenties and thirties and had grown up during the 2000s in rural areas of their homeland where they had been under suspicion of being potential ‘terrorists’ or ‘extremists’ most of their teen and/ or adult life. Several had spent time in prison on crimes related to religious observation, and all of them had left China due to the intense pressure they felt from security organs. In this context, they held intense animosity towards the Chinese state and viewed it as an occupying power in their homeland, but they had no real interest in the ideals of global jihad. It is notable that all of these people had eventually left TIP’s base in Syria to return to Turkey, suggesting that they had eventually become disenchanted with fighting somebody else’s war. However, the number of such Uyghur returnees from Syria in Turkey at the time of this book’s publication were significant. As one Uyghur resident of Istanbul suggested of his neighborhood during the summer of 2019, about one in three Uyghur men on the street had been in Syria.

A second group of Uyghurs who have been associated with TIP in Syria appear to have come there for economic reasons. This is especially true of Uyghur families who came to Turkey via Southeast Asia, having given all of their money to human traffickers. Such people were generally impoverished upon arrival in Turkey and were given little to no assistance by the Turkish state. In Syria, these people were promised housing, food, clothing, and education for their children. In other words, these Uyghurs came to Syria not to fight, but to find a peaceful and prosperous life. Unfortunately, they must also fight a war in order to receive these benefits. Finally, it is likely that a certain number of Uyghurs who came to Syria to fight with TIP have become true believers in the ideology of global jihadism. They likely joined TIP for either of the above-mentioned reasons rather than with the aspirations of contributing to global jihad, but they have stayed with the group because they have found a community of like-minded people, and they are now dedicated to the idea of fighting not only for the Uyghur nation, but also for the Muslim faith.

TIP in Syria is, in many ways, the most obvious manifestation of the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ initiated by the PRC when it began its campaign to assert the existence of a ‘terrorist threat’ within its Uyghur population in the early 2000s. As one Uyghur I interviewed in Turkey who had fought with TIP noted, ‘why does the Turkistan Islamic Party exist? [it] profited from the Chinese oppression of our homeland; without that, it would not exist; China itself made the Turkistan Islamic Party.’ The Uyghurs who have joined TIP in Syria are not the product of a cohesive history of Uyghur ‘terrorist groups’ or a Salafist movement inside their homeland. They are refugees from China’s ‘war on terror,’ who have been driven to fight in a foreign war far from their homeland, either in the hope of one day using their experience to fight the Chinese state or merely as a means of survival and a sense of belonging.

THE GATHERING STORM

In many ways, the substantial army of Uyghurs with TIP in Syria is a creation of the Chinese state. It is the product of the conditions in the Uyghur homeland that, as described above, were facilitated by the narrative that the PRC had been cultivating since 2001 about the ‘terrorist threat’ that existed within its Uyghur population. At the same time, this army also continues to help feed that narrative and contribute to its use by the PRC against the Uyghur people. However, this point should not be confused with direct causation for the cultural genocide that was set in motion in the Uyghur homeland in 2016–2017. I do not agree, for example, with the premise of a recent academic article in the field of ‘security studies,’ which argues that the mass internment, invasive surveillance, and forced assimilation that Uyghurs in China have confronted since 2017 is primarily the outcome of the Chinese state’s fears of TIP’s active presence in Syria.132 Rather, by 2016, there was a gathering storm of factors that were leading the state towards its subsequent policies in the Uyghur homeland, and the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ of TIP in Syria was only one component of that storm.

PRC settler colonization of the Uyghur region had been steadily intensifying since the 1990s, and it had sparked an ongoing violent conflict with the indigenous population starting in 2009 that was spiraling out of control by 2016, especially in the southern Tarim Basin. This intensifying colonization of the region was also further emboldened by the state’s increasing embrace of the ‘Second Generation Nationalities Policy,’ which provided an ideological premise for blatantly assimilationist policies vis-à-vis the region’s indigenous population. Furthermore, it was also fueled after 2013 by the urgency to rapidly re-make the Uyghur homeland into a critical commercial center in Xi Jinping’s flagship foreign policy project, the BRI, as well as by the leadership style of Xi himself who demonstrated that, more than any Chinese leader since Mao, he believes the Party can employ force to solve complex socioeconomic issues, including ethnic tensions born of a long-term colonial relationship.

The drive to settle and colonize the Uyghur homeland and make it an integral part of the PRC would be the primary and root cause of the campaign of cultural genocide that would begin in 2017. The narrative of the ‘terrorist threat’ posed by Uyghurs to the PRC would be its justification and would expediate its implementation. This narrative had been used to dismiss the core causes of the violent resistance to colonization and related aggressive assimilation measures that had been transpiring in rural Uyghur communities since 2011. Additionally, it had been used to justify the violent repression of the resistance, ostensibly further fueling this resistance and helping to establish the self-perpetuating cycle of violence between the state and civilians in the south of the Uyghur homeland. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the narrative’s inherently biopolitical understanding of a ‘terrorist threat’ as a contagion within a given population allowed the state to target all Uyghurs, and eventually Uyghur identity itself, as potentially being part of this threat and, thus, requiring quarantining or eradication.