Honorable William “Bill” Cohen, Secretary of Defense, Senator (R-ME), and member of House of Representatives (R-ME)

Representative G.V. “Sonny” Montgomery (D-MS), Chairman, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

SONNY’S SUMMARY

My friend Bill Cohen, a former Secretary of Defense, United States Senator, and Representative, graciously highlights in his own words my nearly 40 years in public life. This included 30 years representing Mississippi’s Third Congressional District, chairing the Veterans’ Affairs Committee for 14 years, and serving under seven presidents. Secretary Cohen also speaks about how we successfully worked together on national defense issues, even though he and I were from different generations, regions of the country, bodies of the legislature, and political parties. Senator Cohen’s early leadership and long-term commitment to creating a permanent New GI Bill made a real difference.

Mr. Cohen

Bill Cohen

Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Bill Cohen. You’ll be joining G.V. “Sonny” Montgomery on the long and sometimes bumpy legislative road traveled by a measure that Congress enacted into permanent law in 1987… the All-Volunteer Force educational assistance program known as the “Montgomery GI Bill.” The forerunner of the Montgomery GI Bill was the “New GI Bill” enacted in 1984, also under Sonny’s leadership.

I’m honored that Meridian’s Montgomery Institute and Mississippi State University have asked me to introduce Sonny Montgomery to America’s government, public administration, public policy, and politics students.

Through a lifetime of public service, Mr. Montgomery has been able to work with persons in all branches of government and both political parties.

Indeed, when I was Secretary of Defense, a U.S. Senator and a Congressman, Sonny and I worked together, especially on the All-Volunteer Force educational assistance program that bears his name. His vision and leadership made a difference.1

It did not matter to Sonny that I was a Republican and he was a Democrat; or that I was a Senator and he a Congressman; or that I hailed from Maine and Sonny from Mississippi; or that he and I were from different generations. And it didn’t, because Sonny’s rural roots made him what we call a “workhorse” rather than a “show horse.” Sonny knew how to work with people as a team and treat them with respect. He had good ideas, and he was a powerful listener.

They say that “politics is the art of the possible.”2 I’m not sure it’s just politics, though. I think that a good idea—one that stands or falls on its own merit—becomes the art of the doable.

Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1966, G.V. Montgomery represented Mississippi’s Third District in Congress for 15 terms, serving under seven presidents. His autobiography, Sonny Montgomery: The Veteran’s Champion, provides a very personal history of his nearly 40 years in public life.3

Sonny during World War II.

Sonny’s advocacy for veterans, the lodestar of his career, came from personal experience and conviction. During World War II, as a young lieutenant serving with the 12th Armored Division, he helped capture a German machine gun nest and earned the Bronze Star Medal for Valor.

He returned to duty with the 31st National Guard Infantry Division during the Korean Conflict. He had a long and distinguished career in the Mississippi National Guard, retiring with the rank of Major General. His military service spanned 35 years.4

Sonny’s senior portrait from Mississippi State University.

Sonny graduated from Mississippi State University in 1943, where he was president of the student body. When it was time to go to college, Sonny sold some family farmland in Oktibbeha County, Mississippi, to pay for it. Sonny’s rural roots make him plain-spoken. I like that.

George H.W. Bush and Sonny were both elected to Congress in 1966. They were sworn in during the same ceremony in January 1967. They personally met later that day in the House gym.5

George H.W. Bush and Sonny as freshmen in Congress.

And they’ve been friends ever since.6 Sonny’s bipartisan spirit and vision for the men and women of our military made it easy for me to work with him.

Sonny, First Lady Barbara Bush and President George H.W. Bush remained close friends throughout his life.

A champion of veterans, Sonny often visited soldiers in the field during the Vietnam Conflict.

Indeed Sonny spent each Christmas—from his freshman year in Congress in 1967 until the Vietnam Conflict ended in 1973—visiting our soldiers in the field.7

Sonny’s portrait hangs in the Veterans’ Affairs Committee hearing room in the House of Representatives. The National Guard Association of the U.S., the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims and other organizations also display portraits of Sonny in their offices.

Thank you for the privilege of introducing Sonny Montgomery. I think you’ll learn a good deal from him about the art of legislative leadership. Greatest luck to each of you.

Sonny’s portrait at the National Guard Association of the U.S. in Washington, D.C.

Mr. Montgomery

Thank you, Mr. Secretary. I appreciate your kind words.

We have worked together on many legislative initiatives and especially on the Montgomery GI Bill.

Senator Cohen’s early leadership and long-term commitment made a real difference. Indeed, working primarily with the Non Commissioned Officers Association of the United States and the National Association of State Approving Agencies as early as 1979, Senator Cohen introduced legislation that would create a better GI Bill to encourage educationally motivated young men and women to consider military service.8

Again in 1983, Senator Cohen and Senator Bill Armstrong (R-CO) introduced similar legislation and stood on the Senate floor making what they felt was a persuasive case for improved All-Volunteer Force education benefits, only to be narrowly defeated on procedural grounds.9 Indeed, I believe Bill Cohen personifies public service. Bill Cohen served in the U.S. House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate, and on the President’s cabinet. I think that’s pretty extraordinary.

In 1974, during his very first term in Congress, Time Magazine named Bill Cohen as one of “America’s 200 Future Leaders.”10

Mr. Cohen attained national prominence as a freshman Republican Congressman when the House Judiciary Committee selected him to build the evidentiary base for the impeachment of President Richard Nixon. In the Senate, he served as Chairman of the Committee on Aging and Vice Chairman of the Select Committee on Intelligence.

After 18 years of distinguished leadership in the Senate, President Bill Clinton asked Senator Cohen to serve as Secretary of Defense. This represented another “first”—because it was the first time I know of in modern U.S. history a President chose an elected official from the opposite political party to be a member of his cabinet.11

Following 31 years of public leadership, Secretary Cohen leaves behind a record of unparalleled accomplishment, integrity, and respect.12

He leaves something else behind, too: an important part of the title of this book is our use of the word journey! On May 13, 1987—some eight years after he first introduced legislation—the Senate approved H.R. 1085 that created the Montgomery GI Bill by a vote of 89-0.

Noted Senator Cohen on the Senate floor in 1987, “the battle was not an easy one…. This is truly a historic day, and it is all the more remarkable when we consider how difficult the journey [emphasis added] has been….”13

Mr. Secretary, your vision and durability played a special role in our informal team reaching its destination. And your vision continues today in international business.

Thank you again, sir.

Working with then-Senator Cohen and a fabulous team of many people14 over about seven years to create a permanent GI Bill educational assistance program for our youth proved to be a wonderful experience.

As I said on the House floor when the House passed the Montgomery GI Bill legislation March 17, 1987, I was one man on an informal team of people committed to making our “all-volunteer” military successful and offering post-service educational opportunity to our youth. It was a team effort and not really about me.15

When I say our informal team, I mean members of Congress, leaders from each military service, representatives of the veterans/military personnel16/higher education groups, certain members of the media, and some courageous leaders in the executive branch who all worked cooperatively to make the bill a reality.

Here’s how it started. We discontinued drafting 19-year-old men into our military in 1973.17 By 1980, I thought our all-volunteer military concept would fail if we did not create a quality, post-military service educational scholarship as an incentive for our youth to serve, and to give them access to post-secondary education and training, as well.

My colleagues and I felt we would get better enlistees through an educational incentive than we could with, for example, a one-time cash bonus to enlist. Monetary bonuses could be used to encourage our youth to serve in specific, hard-to-fill military occupational specialties; these especially included Army combat arms specialties—infantry, armor, artillery, and combat engineer.

We called this post-service educational incentive the New GI Bill. My colleagues and I began working on a New GI Bill in 1980 and introduced legislation to create it in 1981. It was a New GI Bill in that—for the first time—America would use the GI Bill to encourage youth to enlist voluntarily instead of drafting them. The New GI Bill was also a new concept because it would exist permanently, whether or not the nation was at war.

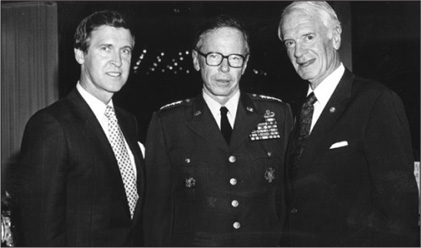

Senator Cohen, General Maxwell Thurman and Sonny in 1985.

The New GI Bill replaced a much weaker and less attractive program called the Post-Vietnam Era Educational Assistance Program, commonly known as VEAP, established January 1, 1977, in Public Law 94-502. VEAP proved largely unsuccessful because few service members signed up for it or used it. (We discuss VEAP later in our journey.)

Congress initiated the New GI Bill for a three-year period. It was limited to service members entering the military from July 1, 1985, to June 30, 1988.

As part of this 1985-1988 test program, America’s youth responded to the New GI Bill in droves,18 particularly those who scored in the upper quartiles on the Armed Forces Qualification Test.

In 1987, after extensive debate and a highly effective lobbying effort by parts of the higher education, the military personnel, and veterans communities, Congress made the New GI Bill the law of the land, as a permanent program. To my surprise, Congress named it after me. I was deeply honored.

But many people shared and guided our vision for this different kind of GI Bill program. In many respects, the Montgomery GI Bill represents the first permanent GI Bill in the history of our republic.19

As I see it, the story of the Montgomery GI Bill is one of national purpose, initiative, and opportunity.

Since 1985, more than 2.3 million former servicemen and women have used it for post-military education and training.20

Currently, as private citizens, these veterans represent valued leaders of our domestic economy as teachers, engineers, doctors, bankers, pilots, law enforcement officials, firefighters, small business owners, public servants, and many other professions.

Folks, I’d like each chapter’s “lessons learned” to speak to the realities of writing laws rather than generalities associated with legislative theory. What did you learn in this chapter?

Sonny’s Lessons Learned

I’d say what I’d want you to learn is the way Senator Bill Cohen and I worked together for seven years, even though Mr. Cohen and I were different in so many ways. We came from different political parties, parts of the legislature, regions of the country, and generations. Success requires reaching out to people. And it worked both ways—me to Mr. Cohen, and he to me. We all get things done through and with others, especially in a democracy.

WHAT’S NEXT

Let’s move to both the origin and unique history of the World War II GI Bill of Rights. My colleagues and I like to think of the Montgomery GI Bill as the modern day version—and “direct descendant”—of this hugely successful education and training program that we’ll learn about in Chapter 2.