Jill Cochran, Staff Director,

Subcommittee on Education,

Training, and Employment,

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs,

U.S. House of Representatives

Senator Alan Cranston (D-CA),

Chairman, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

Senator Frank Murkowski (R-AK),

Ranking Member, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

Senator Spark Matsunaga (D-HI),

Member, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

Lieutenant General

Earnest Cheatham,

U.S. Marine Corps

Dennis Shaw, Deputy Assistant

Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs

Allan Ostar, President,

American Assn. of State Colleges and

Universities

Chris Yoder, Republican Professional

Staff Member, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

Representative

Lane Evans (D-IL)

Lieutenant General Bob Elton, U.S. Army

Vice Admiral Dudley Carlson, U.S. Navy

Lieutenant General Thomas Hickey, U.S. Air Force

SONNY’S SUMMARY

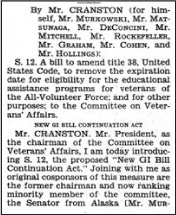

When we introduced H.R. 1400 in 1981, we had just five original cosponsors. When we introduced H.R. 1085 in 1987, we had 174 original cosponsors. From its beginnings on July 1, 1985, through early 1987, the New GI Bill test program showed recruiters could penetrate the college-oriented population of young Americans. Without it, they were generally restricted to employment-oriented young people. The Veterans’ Affairs Committee leadership, especially that of Senators Alan Cranston and Frank Murkowski, introduced S. 12 to make the New GI Bill permanent. Their leadership largely neutralized OMB’s initial opposition to S. 12 and helped engender support from the three-star personnel chiefs of each service branch testifying at the February 2, 1987, committee hearing. The committee approved S. 12 on February 26. We now had real Senate energy on this issue. The House Committees on Veterans’ Affairs and Armed Services marked up H.R. 1085 unanimously on March 4 and March 11, respectively.

Mr. Montgomery

As you recall, from March to about October 1986, our team prevailed over both a proposed return to VEAP—the less financially attractive Veterans’ Educational Assistance Program—and a proposed return to a military draft.

Before we proceed to 1987, the seventh and final year my colleagues and I worked on creating a permanent New GI Bill,1 I’d like to share with you some data on the three-year New GI Bill program initiated July 1, 1985, that shows how it fared as a recruiting tool. The November 14, 1986, briefing paper crafted from various sources by Ms. Jill Cochran, staff director, Subcommittee on Education, Training, and Employment, is instructive. I’ll ask Ms. Cochran to paraphrase from the summary:2

Staff Director Jill Cochran with Sonny at subcommittee hearing.

Ms. Cochran

“Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

• “According to the Army, 35 percent of today’s recruits cite the educational benefits as their principal reason for enlisting.

Upper mental category recruits, the high-quality individuals the services increasingly need, are attracted by education benefits, not bonuses.

• “The Army estimates that the loss of the New GI Bill would result in an annual reduction of 6,000 upper-half high school graduates. This would, in turn, increase attrition by 1,400 losses at a cost of $25+ million. The Army expects a 10-percent lower job performance from those who replace the high-quality personnel.

• “The New GI Bill has already improved the Reserve components’ recruiting effort. High-quality recruits in the Army Reserve components increased 24 percent the first 12 months of the New GI Bill. High school graduate recruits increased 9 percent and six-year enlistments increased 28 percent.

• “The Army estimates the loss of the New GI Bill would result in a loss of 6,300 high school graduates, 6,100 upper-half TSC [test score category] recruits, and 9,500 six-year enlistments.

• “The New GI Bill allows recruiters to penetrate the ‘college-oriented’ population of young people. Without it, they are restricted to ‘employment-oriented’ young people.

• “There is currently in the Department of Education a ‘GI Bill without a GI;’ $3.82 billion in Pell grants are available with no requirement for service.3

• “As a readjustment mechanism for veterans returning to civilian life, an incentive to attract high-quality young people into military service, and a prudent investment in our nation’s human resources, it would be difficult to design a better program than the New GI Bill. The size of this program in dollars in return for service to the nation pales in significance to the massive Pell educational grant program of close to $4 billion annually, which is provided with no expectation of service to the nation whatsoever. The Army and the nation can’t afford to have the New GI Bill killed.”

Mr. Montgomery

Generally, the Army signs up almost as many recruits as the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard put together.4 By the end of 1986, my colleagues and I felt the Army and National Guard units were clearly furnishing potential recruits something they wanted to buy—post-service educational opportunities.

Frank Mensel, vice president for Federal Relations, American Association of Community and Junior Colleges, observed to me in a November 12, 1986, letter:5 “The presentations that the National Guard is now making at conventions and other meetings around the country are superbly supportive. They are selling the New GI Bill as the best American invention[s] since peanut butter and lipstick.”

The historic 100th Congress meets in January of 1987.

It’s now January 1987, the opening of the historic 100th Congress. Every two years we have a new, numbered Congress. After the founding fathers created the Congress in Article I, Section 1, of the Constitution, adopted by the Constitutional Convention on September 17, 1787, the first Congress met in 1789 in Federal Hall in New York City.6 Each Congress has two sessions—one for each of the two years of that numbered Congress.

The service branches had been using the New GI Bill as a recruiting tool since July 1, 1985, and data has become available.

Knowing that the three-year New GI Bill test program would expire in one year and likely revert to the ineffective VEAP program, Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee7 Chairman Alan Cranston of California introduces legislation to convert the New GI Bill test program to what my colleagues and I viewed as a permanent, peacetime GI Bill.

Senator Cranston has been on the case for about seven years now.8 Following a month of informal discussions between committee staff and representatives of the service branches as to how best to shape the bill,9 Chairman Cranston introduced S. 12 on January 6, 1987:10

Mr. Cranston

“Mr. President, I rise today to introduce the proposed ‘New GI Bill Continuation Act.’ The New GI Bill now allows recruiters, for the first time, to penetrate the college-oriented market of young people that we need to operate our sophisticated weaponry… to enhance our preparedness for the complexities of modern warfare.

Alan Cranston

“It is vital that we do everything necessary to make the All-Volunteer Force work and to avoid returning to conscription to meet our uniformed services personnel needs.

“The last thing our nation needs at this point—especially for its young people—is a return to the divisiveness that inevitably accompanies a military draft.”11

Mr. Montgomery

Eight other Senators cosponsored the legislation, including the committee’s ranking minority member, Senator Frank Murkowski of Alaska.

Mr. Murkowski

Frank Murkowski

“I am proud to be an original cosponsor of S. 12, which will make this important and necessary veterans’ education program a permanent part of the benefits programs we rely upon to reward our veterans for their service and to assist them in their readjustment to civilian life….

“Balancing the obligation of the nation to individual citizens against the obligations of individual citizens to their nation [emphasis added] is one of this body’s most important functions.12 This interlocking tapestry of duty and responsibility is perhaps nowhere more vivid than in the protection of our independence and liberty….

“… [A] service member who knows that an honorable discharge will create an opportunity for education is more likely to provide enthusiastic and honorable service than one whose enlistment was motivated by the prospect of immediate gratification from a bonus or high rate of pay….

“… [I]n addition, the service member is more likely to derive long-term advantage from an investment in education than from the pleasures and objects which can be purchased with ready cash. This advantage, like the advantage to the nation of skilled, knowledgeable citizens, will last throughout the individual’s lifetime….

“… [T]he New GI Bill is an important step in the necessary process of ensuring that those who have served in our armed forces will be able to obtain the education necessary to participate in the decisions that shape American life; not just at the highest levels of national power but also on the shop floor, in small businesses, in school, church, labor and fraternal organizations, in the media, and on the street.

“It is critical for the nation—that understands the capabilities and limits of military power—that the graduates of America’s higher education include those who have served in the armed forces.”13

Mr. Montgomery

Also cosponsoring S. 12 was Republican Whip Alan Simpson. When Mr. Simpson was Speaker of the Wyoming legislature, he was known as the “fastest gavel in the West!”14

Alan Simpson

As we discussed in Chapter 4, a “whip” mobilizes the vote within his or her political party based on legislative priorities and policy positions and decides when bills are scheduled for a floor vote.

S. 12 proved unique because Alan Cranston was the Democratic Whip and Alan Simpson was the Republican Whip. Both sat on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee. How about that?

An original S. 12 cosponsor was Senator Spark Matsunaga of Hawaii, a decorated Army combat infantryman who graduated from Harvard Law School on the World War II GI Bill. “Sparky” earlier led Hawaii’s quest to become a state.15 And he was an original cosponsor of the All-Volunteer Force Educational Assistance Act of 1980 (S. 3263) with Senator Cranston and others.

One of the best-liked members of the Senate, Mr. Matsunaga offered some humor at the February 4, 1987, Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee hearing on S. 12 by telling the witnesses how traveling from Washington, D.C., to Hawaii messed up his body clock…

Mr. Matsunaga

Spark Matsunaga

“Ladies and gentlemen, I can live with the six-hour time change, but the only problem is, I get sexy at meal time and hungry at bed time.”16

House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, 1987.

Mr. Montgomery

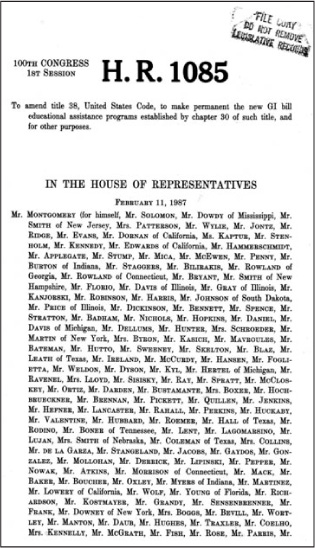

Back on the House side, on February 11, 1987, 174 members of the House (out of 435) joined me in introducing H.R. 1085, legislation comparable to S. 12. This time we didn’t wait for our familiar H.R. 1400 bill number to become available because of good energy in the Senate with its introduction of S. 12!

When we first introduced H.R. 1400 in 1981, we had only five original cosponsors,17 a far cry from the 174 who joined us in 1987!18

Were we pleased that the Senate had a bill very similar to ours? Heck, we were happier than lost kittens in a creamery!19

As I mentioned, on February 4, 1987, the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee held its public hearing on S. 12.

The Committee took testimony from 22 witnesses,20 including the Chief Benefits Director of the Veterans Administration,21 Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Management and Personnel,22 and the three-star personnel chiefs from the four service branches. (The committee inadvertently neglected to invite the Coast Guard, as it was under the jurisdiction of the Transportation Department.)

The witnesses—including the four personnel chiefs led by the Army’s Lieutenant General Bob Elton, a West Point graduate who had a master’s degree in physics—all supported a permanent New GI Bill. General Elton was the first witness and told the committee:23

Lt. Gen. Elton

Lt. Gen. Bob Elton

“Mr. Chairman, we strongly support this valuable recruiting incentive. We have managed to save about a division’s worth of manpower each year. We save between $200 million and $250 million per year in the way of recruiting costs and additional training because these recruits [who respond to an educational incentive] just stay around longer.”

Vice Admiral Carlson testified:24

Vice Admiral Carlson

“We in the Navy totally endorse the New GI Bill…. We have seen our percentage of those signing up for the GI Bill in our new recruits increase dramatically over time; and in December [1986], we were having new recruits signing up for the GI Bill at 58 percent of those coming on board….”

Air Force Lieutenant General Hickey told the Committee:25

Vice Admiral Dudley Carlson

Lt. Gen. Hickey

Lt. Gen. Thomas Hickey

“We do, in fact, see the New GI Bill as a very potent recruiting tool…. Not only have we had a significant increase in participation of our new recruits, we have found that the vast majority of those who do participate are in the top two mental categories. So, we are getting the kinds of quality that we are interested in.”

Lieutenant General Earnest Cheatham, U.S. Marine Corps, observed:26

Lt. Gen. Cheatham

“In excess of 65 percent of the people that come in now—and are talking to us—are talking about the GI Bill. It brings people to us—good quality people. We support it, and we love it. It is a No. 1 priority for our young people.”

In his testimony, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs Dennis Shaw said:27

Lt. Gen. Earnest Cheatham

Mr. Shaw

“… During FY 1986, 34,500 more Selected Reserve recruits were high school graduates than in FY 1984, the last full year preceding the effective date of the New GI Bill.”

Dennis Shaw

Mr. Montgomery

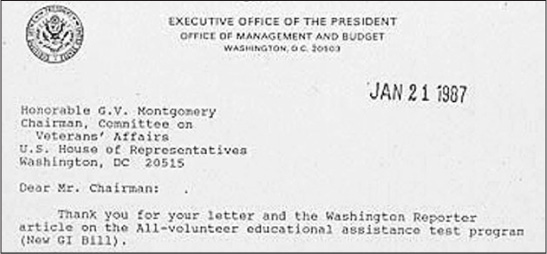

OMB supported making the program permanent,28 as stated in the February 4, 1987, testimony of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Force Management and Personnel) and Chief Benefits Director of the Veterans Administration, but it proposed a major revision.

The OMB-directed testimony proposed that the Defense Department, rather than the Veterans Administration, fund the New GI Bill program.29 For some 40 years of previous GI Bill educational assistance programs, Congress funded such programs through the VA’s budget.

Neither the House nor Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committees supported this approach because the New GI Bill continued to serve as a tool for ex-GIs to transition from military to civilian life. Like all previous GI Bill programs, the Veterans Administration funds transition assistance programs for former service members—not the Department of Defense.30

What does it say on the top of the letter?

The Office of Management and Budget indeed is part of the Executive Office of the President—no matter who the President is. As we learned earlier, the OMB articulates the President’s position, which is known as “administration policy.”

A key witness for the higher education community was Allan Ostar, then-serving in his 21st year as president, American Association of State Colleges and Universities. Mr. Ostar enlisted in the Army in 1942 and served in Europe from 1944-46 with the 42nd Rainbow Infantry Division. His awards include the Combat Infantryman’s Badge and two Bronze Star Medals for valor. After World War II, he was a beneficiary of the GI Bill at Pennsylvania State University and the University of Wisconsin, Madison.31

Here are some highlights of Mr. Ostar’s testimony:32

Mr. Ostar

Allan Ostar

“… America’s state colleges and universities grant more than 31 percent of bachelor’s degrees each year in the United States…. The GI Bill is an important aid to the quality of American education in general in that it provides confident, motivated students… who bring a sense of responsibility to our nation’s college classrooms…. The strength of our society is based on a strong and balanced relationship between three major elements of American life: the national defense, a productive healthy economy, and an effective system of education. America cannot be strong if any one leg of the three-legged stool is weak. In effect, the GI Bill is a model program for this triad. It strengthens all three. This program uses a military/higher education partnership which strengthens both partners, and our economy and society as well.”

REFLECTIONS ON LAWMAKING

Mr. Montgomery

Folks, let’s pause and reflect a bit.

I never served in the U.S. Senate, but let me offer three thoughts on what I consider some everyday realities of policy making that emerged in the Senate.

The first thought is that the chairman and ranking member of the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee asked the general-officer personnel chiefs representing the service branches simply to appear before the committee to respond to questions.33

To their delight,34 the generals were not required to submit to the committee an official written testimony that would have to be cleared with OMB first.35

This proved an unexpected opportunity because the general officers could state the view of their service branch rather than the executive branch/DoD view.

The second observation is that the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee’s official rules of procedure require witnesses to submit their written testimony to the committee 48 hours in advance of the public hearing.

Practically speaking, this procedure gives Senators and committee staff an opportunity to get a good preview of what witnesses will say.

Further, the written testimony submitted by subject-matter experts representing higher education, veterans, and military personnel groups often contains information/data to help make a persuasive case for the bill in the committee report. Plus, committee staff often used this information in drafting proposed hearing questions for the members they served.

And the third observation is to get away from Washington and talk to the folks on the business end of your proposed policy.

As we discussed in Chapter 11, as I also was the No. 2 ranking member on the House Armed Services Committee, I led a delegation of eight Congressmen and representatives from 30 military personnel and veterans’ organizations to recruit training bases of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force.36 The 30 organizations were very important members of the informal team we formed.

The purpose of the visits was to learn from the recruits themselves whether the New GI Bill “test” program served as an incentive for them to enlist. And if so, to what extent?

The Congressional delegation (known as a CODEL) filed a detailed trip report with the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, citing evidence to support its conclusion that the New GI Bill was bringing quality recruits into the military, rather than doing so through a military draft. The delegation’s report quoted the Adjutant General of Kentucky, General Billy Wellman:

“You give a recruit a dollar today and it’s gone. You give a recruit an education, and the recruit will have it the rest of his or her life. The New GI Bill is a No. 1 priority because of what it offers long range, to the service member, his family, and the service.”37

In February 1987, Sonny led a Congressional delegation (CODEL) on a series of visits to learn from the recruits themselves whether the New GI “test” program served as an incentive to enlist.

Further, the report concluded:

“The delegation believes that the New GI Bill is accomplishing those purposes for which it was created. Recruits entering the armed forces have available to them an excellent educational assistance benefit which will facilitate their readjustment to civilian life following military service. The military services have a powerful, cost-effective tool which is aiding in the recruitment and retention of high-quality young people. New GI Bill implementation, as observed by the delegation, is being carried out effectively by all services.”38

My colleagues and I advanced the notion that a permanent, peacetime GI Bill and the All-Volunteer Force concept were directly linked.39

We used the word “peacetime”40 because the New GI Bill would exist for our veterans whether we were at war or not. The New GI Bill wouldn’t “come and go,” as wars came and went. It would be there permanently, including in peacetime.

The Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee also met in open session on February 26, 1987, and unanimously reported the Cranston/Murkowski bill with certain amendments.41 Through the amendments, the committee added new “purpose clauses” to the New GI Bill.42

What would you think is meant by a “purpose clause” in a law—in this case for the New GI Bill?

Charles “Chris” Yoder served as a professional staff member on the Republican staff of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs.

A big part of Mr. Yoder’s job was to advise the committee conceptually as to what legislation both should say and do.43

I’ll ask Chris to talk with you about a declared purpose clause in a law.

Mr. Yoder

“Thank you, Mr. Chairman. “A purpose clause describes a law’s objectives—what Congress wants a law to do. In effect, objectives in a law reflect the objectives of United States policy, as stated through an act of Congress. These objectives should be clear and, to the greatest extent possible, they should be measurable—quantifiable—if you will.

Chris Yoder (far right) with Chairman Montgomery (center) and, left to right, staffers Deborah Lee, Darryl Kehrer, Jill Cochran and Karen Heath after the signing of the Montgomery GI Bill enrolled bill (H.R. 1085, as amended) in Statuary Hall.

“Senator Murkowski asked Veterans’ Affairs Committee Republican Chief Counsel Anthony Principi and me whether Congress should create additional purpose clauses for a New GI Bill. After reviewing the body of testimony from the February 4 hearing, we suggested that Mr. Murkowski do so in an amendment to S. 12 during committee mark-up—preferably on behalf of himself and Chairman Cranston.

“Congress had designed the various GI Bill education programs over the decades for a ‘different era, a different economy, a different society, a different technology, and in fact, a different (non-conscripted) veteran.’44 But the obligation of the nation to those who serve has remained the same.

“So Senator Murkowski proposed three additional purpose clauses during mark-up of S. 12 for the New GI Bill, the first two of which Congress had enacted as part of the Vietnam-era GI Bill education program:45

• Extending the benefits of a higher education to those who might not otherwise be able to obtain such benefits;

• Providing vocational readjustment and restoring lost educational opportunities; and

• Enhancing our nation’s competitiveness through the development of a more highly educated and productive workforce.

“With respect to the first two new purpose clauses above, the House Veterans’ Affairs and Armed Services Committees, too, would add such clauses at markup a few weeks later. And the full House would embrace the third one in May.

“With respect to the third new purpose clause, a banker and businessman by education, Mr. Murkowski held the view that ‘the challenge to American economic world leadership has never been greater. Our competitive edge depends upon a skilled labor force. Critical, sophisticated, new-growth industries—computers, robotics, and biotechnology to name a few—demand workers skilled in technology and a populace conversant with the rudiments of science…. Our nearest world competitor, Japan, recognized the importance of education for its own future 25 years ago [1962], when its Economic Council declared, ‘Economic competition among nations is a technical competition that has become an educational competition.’46

“Workforce development was an important issue. Our ability to compete internationally in the new, emerging world economy very much was a topic of Congressional debate in 1987.47

“Senator Murkowski viewed those who serve in our military as engaging leaders and as a competitive business asset due to their discipline, energy, and reliability. Add in their ability to gain civilian skills under a New GI Bill and indeed they would become a unique national resource for America.

“Appropriately, Congress ultimately added these three purpose clauses to the Montgomery GI Bill, as signed into law by President Reagan.”48

Mr. Montgomery

The House Veterans’ Affairs Subcommittee on Education, Training, and Employment held its public hearing on February 18, 1987,49 one week after the trip to the recruit training sites.

On March 4, 1987, the subcommittee voted in open session unanimously to report a permanent New GI Bill to the full House Veterans’ Affairs Committee.

I must say, the full committee’s work on the bill brought an unexpected surprise and high honor for me, as its chairman.

Before reporting H.R. 1085 on March 4, the full Committee unanimously approved Congressman Lane Evans’ amendment to name the GI Bill the Montgomery GI Bill Act of 1984. In offering his amendment at the full committee mark-up, Mr. Evans commented on my role in the proposed legislation:

Mr. Evans

“You had the vision to conceive the New GI Bill. You had the courage to fight for it against strong and committed opposition. You had the leadership needed to succeed. It has done what you said it would and even more.”50

Lane Evans

Mr. Montgomery

Lastly, the House Armed Services Committee also marked-up H.R. 1085 on March 11.51 In so doing, the committee rejected a proposal included in President Reagan’s FY 1988 Budget to shift funding for the New GI Bill benefit from the VA to DoD.52

Here is some of the language from the report the House Armed Services Committee filed following the committee’s March 11, 1987, vote in favor of H.R. 1085.53

“Based on the information available to date, the committee is convinced the New GI Bill is a highly successful program. The committee will not restate the wealth of backup data provided in Part I of the report on H.R. 1085 filed by the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. Participation rates by service members have far exceeded even the most optimistic predictions when the legislation was formulated two- and a-half-years ago. Witnesses before the committee have uniformly endorsed the continuation of the New GI Bill as a vital tool to maintaining the outstanding recruiting and retention results currently experienced by the services.

“The Army’s success during fiscal year 1986, the first year of experience under the New GI Bill, illustrates the importance of a viable educational assistance program. In fiscal year 1986, the active Army—the service that traditionally has experienced the greatest difficulty in recruiting goals—recruited 91 percent high school graduates, with only 4 percent in Mental Category IV, the lowest Mental Category eligible for enlistment. In the Army Reserve, Mental Category I-IIIA, the cream of the crop in recruiting, increased 24 percent and six-year enlistments increased 28 percent during the first year of the New GI Bill in comparison to the previous year.

“The committee believes the test program has been an unqualified success and, therefore, recommends that the June 30, 1988, expiration date for the New GI Bill be eliminated, thus making the program permanent.”

So we were positioned to take the bill to the House floor.

Sonny’s Lessons Learned

Finding common ground pays dividends. Chairman Cranston and ranking member Murkowski jointly introduced S. 12. Their doing so proved a bipartisan advantage. They were together on the issue, sharing the same view as to an educational assistance policy for our All-Volunteer Force. And seven other Senators of both political parties joined them as original cosponsors of the bill. These included the Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell of Maine, Senate Minority Whip Al Simpson of Wyoming, and the venerable Strom Thurmond of South Carolina. All served on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee.

WHAT’S NEXT

Let’s move to the final few months—April, May, June 1987—that put the New GI Bill on the President’s desk.