Insomnia

InsomniaKelli was thrilled to get pregnant. As a serious club tennis player, she was already in fantastic shape, so her doctor assured her she’d sail through pregnancy. A week later she started to puke. And gain weight. And hate everyone.

Her husband, Hector, dutifully backed off their regular sex schedule (usually about twice per week), telling himself it was only temporary and that she obviously felt wretched. Besides, she didn’t seem like she’d be much fun to play with right now.

After three months, Kelli’s hormones calmed down and she stopped puking. As her belly got rounder, she gradually seemed like her old self, and resumed being nice to everyone—except her husband. In particular, she didn’t want to have sex with him. She didn’t even want to kiss him, saying his breath made her nauseous.

Unlike some other husbands who tease, embarrass, or reject their pregnant wives, Hector was still affectionate, regularly telling Kelli how attractive she was and how he desired her.

Meanwhile, she was getting bigger and bigger, and she didn’t like it one bit.

At first she had various reasons for her withdrawal from Hector, then excuses, and in their first big blowup about it, she accused her husband of being insincere about finding her attractive in her current state. Stunned, he told her how beautiful she was. “You’re just desperate to get laid after all these months,” she scolded. When he denied this, she just got angrier. After weeks and weeks of this recurring battle, she said, during a session, “He doesn’t really want me, he’s just trying to make me feel better. Well, I can see right through him, and it’s not working. I’m not an idiot—I know I look like a damn whale.”

Kelli claimed she could live with Hector being honest and rejecting her while pregnant, but she couldn’t stand what she perceived as his dishonesty, “obviously” patronizing and manipulating her.

Hector was baffled and hurt, and after trying to connect with her for months, he withdrew. The situation was looking worse and worse. I also had my eye on the calendar: in just eleven weeks Kelli would give birth, and their lives would really be turned upside down. That would be no time to put the marriage back together; I really wanted to do it now, accomplishing as much as possible before she gave birth. In some ways I had a stronger sense of urgency than they did, never a good setup for therapy.

How could I get Kelli to consider the possibility that Hector was telling the truth, and that she was actually expressing her own disgust about herself? “Kelli, what if he’s telling the truth?” I asked. “Then,” she replied angrily, “either he doesn’t care how I look anymore, which sucks, or he never really saw or cared about how I looked before, which sucks, or I’m making this whole thing up and I’m crazy. I don’t know which is worse.”

The first two were completely false.

Truly, she was projecting her self-rejection onto him. For years she had been highly identified with her body—not so much her looks, but her mobility, gracefulness, and feline trimness. She had lost these—and was afraid she’d never get them back. She’d think about it, feel selfish for thinking about it, wonder if getting pregnant had been such a good idea, and then start the cycle again.

One week, out of nowhere, she asked, “Is it safe to have sex while I’m pregnant?” It turned out she was also afraid that she’d lose her sexuality, another thing with which she was strongly identified. I asked what her doctor had said. “Oh, she said it was okay, but I don’t know if I believe her. She doesn’t look like she’s ever had sex, and Hector and I can get, well, you know, we’re both kind of athletic….” He laughed, and she smiled shyly. It was sweet.

“Not only can you have sex now,” I said, “you can also have sex after you give birth.”

“But I hear it takes a year or two before couples have sex again,” she said. “I don’t like that. And how is Hector going to manage?”

I assured her that if it took a year, it took a year; they’d be fine. (I felt this was ultimately more instructive than assuring her that it probably wouldn’t take nearly that long.) Hector made a few jokes, all with the theme of “I’ll wait for you.”

Not only was Kelli concerned about Hector being turned off to her body now; she was concerned that either her body would be “permanently disfigured” and he’d be turned off forever, or that she’d lose weight and regain her old body, but he’d then be turned off by the ugly picture of her that would supposedly be seared into his memory.

“You don’t get it,” the usually calm husband finally said one day. “And I’m tired of it.” Hector hardly ever talked that way. “You seem to have a problem with your looks now, and you seem to be afraid that I’ll think you’re ugly for the rest of our lives. That’s ridiculous,” he said. “You insist you can predict exactly how I’ll feel, but you’re wrong.”

“If necessary,” he continued, “we can go without sex the rest of your pregnancy. That will be lousy, but I can manage it. But we are going to have sex after the baby comes, and it will be just as great as it used to be. Right?” She was impassive. “Right? Right?” He turned to me in frustration.

“It’s never going to be like it was,” she finally said in a voice of quiet desperation. “You’ll be the same sexy guy, so of course I’ll eventually desire you again. So will other women. But I’m ruined forever. You won’t want me, I’m already disgusted with myself, and nobody but losers will think I’m attractive.”

“You’re absolutely right,” I told Kelli, to Hector’s surprise. “It’s never going to be like it was. The question is, can you two make it wonderful in a new way? Kelli, you seem to believe your husband’s sexual interest in you is pretty shallow; with that belief, of course you’re anxious about the future. If you listen, maybe you’ll learn something about Hector.”

Indeed, Kelli had never stopped worrying long enough to realize that Hector desired her for more than her perfect body. “Kelli, I want you to imagine that there’s more than one way Hector can desire you and see you as attractive, more than one way that people can connect sexually. Once you do that,” I said, “everything else is just details. When you insist that Hector is terribly inflexible in his desire for his wife, you’re saying more about your imagination than about his.

“Fortunately,” I continued, “Hector will bring his imagination and his desire for you to your marriage no matter how skeptical or self-conscious you are. His desire for you is like gravity—even if you don’t believe in it, it’s still real. It would be a real waste to insist that Hector doesn’t desire you when he does.”

“You’re asking me to trust him an awful lot,” Kelli said slowly. I agreed. She said she wasn’t sure she could do that just now.

“Yes, maybe it isn’t something you want to do now.”

Kelli noticed my reframe. “You make it sound like a choice,” she said.

Again I nodded: “Yes, I believe it starts as a decision to trust, and then we figure out how to do it.”

Kelli didn’t quite agree, but she noticed that it could give her a way out of her dilemma. That was good enough for me—until our next session, anyway.

Most of us develop our model of sexuality when we have the body of a young, healthy person. Most of us only have that body for a few years, and no one has it more than a decade or two. So if we want to enjoy sex when we develop a different body, we better have a different model of sexuality available.

Without that vision, we will have difficulty sustaining our desire, as we will question our attractiveness and our very eligibility for sexiness. If our partner is close to our age, we’ll have a hard time seeing him or her as attractive or desirable too.

Aging and health issues have tremendous effects on people’s sexual experience. Matters of concern include medication side effects; sex during pregnancy and after childbirth; sexual effects of contraception; reduced stamina or range of motion; menopause; chronic pain; and unwanted changes in the body’s functions, including desire, lubrication, erection, and orgasm.

Using the standards of what a young person’s body can do during sex (stamina, flexibility, desire, erection, lubrication, orgasm, and so on), many people over thirty-five will “fail” at sex over and over. Rather than enjoying what an older body and an older mind can create during sex, too many people focus on comparing who they are with who they were. This is terribly distracting, whether we like the comparison or not.

To enhance sexual satisfaction past age thirty-five, you need to come to terms with this new context for sex. After all, “good sex” for you will never again look like it’s “supposed to”—if that requires two young, healthy bodies. Especially if you (or your partner) have one or more common health challenges, you need to feel empowered to redefine “sexy” to include someone—yourself—in a physical state that society specifically defines as unsexy.

Only then can you take advantage of facts and techniques that can make sex more enjoyable. Otherwise, it’s like taking piano lessons while listening to an iPod. Even the best teaching in the world won’t get through.

As we’ve already seen, it’s important to establish your own idiosyncratic model of sexuality—enjoying what you choose to put in, and grieving what you’ve lost and therefore can’t put in. There’s so much (faux) cheerfulness in the media about “successful aging” and “lifelong sexual vitality” that I think many people underestimate the emotional difficulties. It’s like a travel brochure for Cuba that features the beautiful beaches, the great music, and the gorgeous women but doesn’t mention the grinding poverty.

Common Health Problems with Sexual Impacts

You’ll recall our discussion of “erogenous zones”—how it’s a limited concept, and how the entire body can be the site of sexual feelings.

I believe the concept of sexual “function” and “dysfunction” is similarly limited, because it makes an artificial distinction between bodily reactions that are sexual and those that aren’t. A blinding migraine that turns a romantic weekend into a lonely nightmare is just as much a sexual problem as an unreliable erection or a burning feeling in your vagina.

So before we get into some specifics about health and aging challenges, let’s note some of the “non-sexual” health problems that often have sexual consequences:

Insomnia

Insomnia

Diabetes

Diabetes

Arthritis

Arthritis

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia

Asthma

Asthma

Migraines

Migraines

Hypertension

Hypertension

Degenerative disk disease

Degenerative disk disease

Yeast and urinary infections

Yeast and urinary infections

Lupus

Lupus

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome

Asperger’s syndrome

Asperger’s syndrome

Obesity

Obesity

Hormone disorders

Hormone disorders

Tinnitus

Tinnitus

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Depression

Depression

Dementia

Dementia

Sciatica

Sciatica

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism

Sjogren’s syndrome

Sjogren’s syndrome

… and anything else that makes it hard for people to get along, be nice to each other, spend time together, pay attention, or enjoy their bodies.

If you’re thinking, “Wow, it seems like practically every illness has a sexual component”—yes, I think that’s accurate.

People experience health challenges at all ages, so facing one doesn’t make you “old.” That said, many of the insights and strategies we’ll be discussing here apply in similar ways to the challenges posed to sex by aging.

You’ve already read about a range of Sexual Intelligence tools that will help you understand and approach the sexual challenges of health and aging. These include:

• Talking with your mate

• Letting go of sexual hierarchies

• Realizing that you give sex meaning rather than sex having inherent meaning

• Deciding what your conditions for good sex are and communicating these to your partner

• Letting go of the need for “spontaneity” in sex

Now let’s discuss how to apply these tools and ideas.

Sexual Effects of Medications

Many prescription drugs have sexual side effects, which can undermine desire, slow down arousal, and inhibit orgasm. Some common drugs with sexual side effects are:

• Antidepressants

• Diuretics (used for hypertension)

• Analgesics (pain medication)

• Antihistamines

• Anti-anxiolytics (used for anxiety)

• Anti-epileptics

• Antihypertensives

• Appetite suppressants

• Oral contraceptives

• Cancer chemotherapy

Medications don’t have to affect sexual function directly in order to impact your sexual experience or sexual relationships. Some medications affect sexuality in other ways:

• Making your mouth taste funny

• Making you thirsty all the time

• Making you sleepy

• Making you mentally sluggish

• Making you grind your teeth, snore, or shake

• Requiring you to not drink alcohol

• Changing the smell of your sweat or breath

• Making you prone to depression

Effects like these can inhibit kissing and oral sex, make you less attractive as a partner, alienate you from your own body or sexuality, or simply make sex a lower priority in your life.

Not surprisingly, the sexual side effects of drugs are one of the main reasons people don’t comply with their doctor’s orders about how frequently and for how long to take a medicine. (If that sounds like you, make an appointment with your doctor this week to review and possibly change your drug regimen.)

Unfortunately, many doctors don’t discuss this with patients when prescribing a new drug. The same is true with the pharmacists who dispense them. These professionals should know how common sexual side effects are, and how these side effects often discourage patients from taking their medicine. Doctors and pharmacists should take the initiative to discuss sexual side effects with patients. Unfortunately, shyness, lack of information, fear of the patient’s response, and a misplaced sense of courtesy or propriety often get in their way.

If you do have sexual difficulties while taking medication, you can:

• Talk with your pharmacist

• Talk with your physician

• Talk with your therapist

• Talk with your partner

Also, ask yourself: did my sexual difficulties begin or get worse when I started the medication? Sometimes we feel so glad about the positive impact of a drug that we don’t realize the drug might also be contributing negatively to our lives.

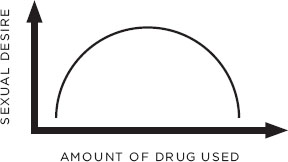

While we’re on the subject, let’s briefly look at recreational drugs. The common ones—marijuana, cocaine, and the amphetamine family—have an interesting effect on sexuality. Most users say that a little bit makes them more interested in sex, while a lot makes them less interested. So while moderation may not be the key to happiness in all things, it does increase the chances that you can enjoy sex when you’re using a street drug.

How Many Street Drugs Affect Sexual Response

Effects of Alcohol on Sexuality

Alcohol is a drug too, and it has well-known effects on the human mind and body.

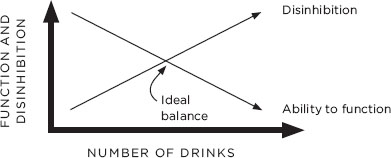

For thousands of years, people have described alcohol as a drug that disinhibits; i.e., it makes people feel more relaxed, less anxious, less embarrassed, more willing to take chances, less concerned with social convention. Thus, it allows people to do things they wouldn’t ordinarily do, or wouldn’t do without discomfort.

At the same time, alcohol reduces the speed of people’s reflexes, reduces hand-eye coordination, inhibits motor discrimination, slurs their speech, and ultimately makes them sleepy. Thus, it makes subtle physical gestures more difficult or even impossible. That’s why both bras and condom packages become harder to open. Alcohol also makes it harder to get or keep an erection and interferes with vaginal lubrication.

So there’s the conflict, which Shakespeare described so well in Macbeth: alcohol “provokes the desire, but takes away the performance.” And so “lechery, sir, it provokes and unprovokes.” That is, it reduces our inhibitions—which many people want regarding sex—but it makes it harder to “perform”—to allow or make our bodies do what we want them to.

Many people want alcohol’s disinhibiting effect (if not on themselves, then on their partner), but they don’t want to pay for it with diminished functioning. After all, what’s the use of being mentally relaxed enough to enjoy sex if your body is asleep or you can’t feel your limbs?

So where is the ideal balance of some disinhibition without too much loss of function? When I ask patients, students, and colleagues to estimate, they often guess three drinks, even four, occasionally five. (Anyone seriously guessing five has either never had a drink, or is incredibly anxious about sex.) While it’s different for each person, the answer for most people is actually about one drink. That’s right—for most people, after only two-thirds of a drink, more alcohol actually degrades the sexual experience by removing more in function than it adds in relaxation and playfulness.

How Alcohol Affects Sexual “Function”

Now, after about one drink, most people believe that more alcohol doesn’t cost them much in functioning—because as we drink we’re typically getting less and less sensitive to what our body is doing and feeling. And because when we’re drunk, almost anything that doesn’t make us angry can seem funny. At the time. You know, “You had to be there.”

So alcohol is another drug that, when it comes to sex—moderation is best.

A Special Note About Chronic Pain

Chronic pain: it’s aggravating, tiring, embarrassing, and it’s a life sentence.

People who have it get tired of talking about it; people who don’t have it get tired of hearing about it. Meanwhile, it’s the silent third party in the bedroom. Sex involves Ron, George, and Ron’s pain.

It’s such a betrayal. Almost everyone with chronic pain remembers when they didn’t have it: “Oh, those were the days!”

No one wants to adjust their lovemaking to chronic pain. It makes someone feel old, weak, vulnerable, self-conscious, not-sexy. Pathetic. And it forces a person to accept the finality of the pain, the fact that it isn’t a temporary problem—it’s a permanent one. That alone is why so many people don’t adapt their lovemaking to their pain—the increase in pleasure simply isn’t worth the depressing reminder of the horrifying truth. No, better for sex to hurt than for sex to be a reminder that this pain is permanent. Better to lose interest in sex than for sex to be a reminder that this pain is permanent.

If you know (or suspect) that your partner hurts during sex, grab him or her, snatch away the Snickers or the TV remote, and tell your partner, “You’re busted!” You’re from the Pain Squad, and you insist that the two of you talk; specifically, how exactly can the two of you adapt your sex so it hurts less? (See, we’re going for less pain rather than no pain—how awful is that already?)

Adapting to reduce pain might be as simple as switching sides of the bed, or switching positions, or using pillows under the butt, shoulder, ankles, or neck. Or it may involve taking ibuprofen or a hot bath a few minutes before sex. Or it may involve a five-minute massage—neck, shoulders, hands, whatever—right before sex, or three minutes of lying quietly and breathing, relaxing the body and visualizing comfortable muscles and joints right before sex. People rarely do that without being pushed. So push. Oh, and then help pick up the pieces of your partner’s existential crisis that results from acknowledging that he or she is living with chronic pain.

Damaged Body Image

In America, we learn to feel ashamed when our body’s outside doesn’t match who we feel we are on the inside. That’s true for the signs of aging (such as wrinkles), as well as for a wide range of other body features: weight, posture, facial asymmetry, fitness, scars, visible injury, and artificial devices (braces, cane, wheelchair, and so on). All these issues can create a contrast between the way we look to others (and, especially, in the mirror) and the healthy, “normal” way we feel on the inside.

We can all understand this. I know I don’t feel like a person my age and my weight—but when you look at me, that’s exactly what you see, and of course you assume that what you see is accurate. That’s one reason many people get upset about their bodies—the body is the vehicle through which, we assume, others are misjudging who we are.

This is a pretty routine, if painful, part of adolescence (a dangerous one for some), but for many people it starts again (or continues) when they reach their thirties, or after childbirth, when they go bald, when they retire, and at many other times. It’s a common complaint: “How could I look this way? I feel sexy (or young), but my body doesn’t look it (at least not to me).”

So our distress is about one, two, or all three of these things: the beauty thing (I don’t look as good as I want to or used to); the dissonance thing (how I look doesn’t reflect who I feel I am); and the definition-of-sexy thing (I know I don’t fit the official definition of sexy, but trust me, I am).

Both aging and illness demand that a person problematize his or her body. Ordinarily, adults wrestling with aging or a disease relate to their troublesome body mostly by (grudgingly) taking care of it and (resentfully) working around it. When your body is the focus of so much frustration, disappointment, sadness, and powerlessness, it can be hard to imagine your body as a focus of your pleasure and of others’ desire and delight.

And so you have to remember that being sexy is about who you are, not how you appear. As someone gets to know and appreciate you, your body comes along for the ride. You should treat your body like an honored guest, not an albatross.

Of course, this is all especially true when you’re in the bedroom and your clothes come off. You feel self-conscious. You’re afraid your partner will be disappointed, perhaps imagining how you looked ten or twenty years ago. If you’re uncomfortable with your body’s appearance, you must, must, must ignore how the damn thing looks and allow sex to happen, uninterrupted by your self-consciousness or judgments. Our culture, of course, is not your ally in this; as sexual anthropologist Mickey Diamond says, “Nature loves diversity. Unfortunately, society hates it.”

What You Can Expect with Aging

Let’s look at some of the common changes you may experience while you age, and compare these with some things about your sexuality that may not change as you get older. What do I mean by “aging” and “older”? Some vague time around forty. But your mileage may vary substantially. Some people are sexually exhausted by thirty, while some late bloomers are just getting started in middle age.

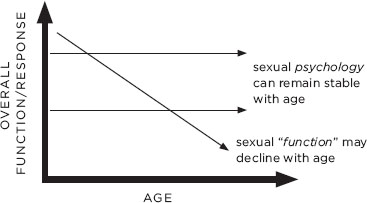

First, what are common changes in sexuality with aging?

• Desire: Often declines.

• Vaginal lubrication: Typically declines in volume and consistency.

• Erection: Requires more stimulation; may not be as hard or last as long.

• Orgasm: May take longer to arrive; may not last as long or be as powerful.

• Refractory period: The mandatory waiting time between ejaculation and next erection often increases.

• Preferences: The typical sexual repertoire may shrink; experimentation often declines. Occasionally it works in reverse: some people who have been inhibited for twenty or thirty years get a new lease on life (new partner? near-death experience? Mom remarries?), and their sexual menu expands as they become more experimental.

Second, how can sexuality remain stable with aging? Whether the following aspects of sexuality start low in youth and stay low throughout adulthood, or start high in youth and stay high in adulthood, they can remain stable over time:

• Desire for closeness

• Desire to be desired

• Desire to feel good in your own body

• Experience of orgasm

• Level of desire

• Content and quantity of fantasy

• Preferences

Sexual “Function” and Age:

Some Changes, Some Constants

So note that while sexual function often changes with age, sexual psychology can remain stable over time. Sexual Intelligence gives you the tools and motivation to shift your sexuality as you get older to accommodate this contrast. That’s one important way in which you can continue to enjoy sex as your body’s ability to do what it used to do declines.

So aging isn’t some thief that steals your sexuality; it steals one version of your sexuality—function-based sexuality. When it does, you get to decide whether or not your sexuality has left you altogether. If you have emotional courage and sufficient interest, you can reinvent yourself sexually, constructing a satisfying sex life from the familiar pieces of your psychology, using it to work around the changes in your function.

The Myth of Reaching Our “Sexual Peak”

A lot of people are concerned about when they’re going to reach their “sexual peak.” Will it be high enough? Will it be at the right time? How will it fit with their partner’s “sexual peak”? When it comes to sex, America seems filled with mountain climbers.

Perhaps human beings have been wondering about this, in one way or another, for a long time. However, Americans today deal with the results of an oversimplified, popularized misinterpretation of a few key facts—repeated so many times that it sounds both accurate and profound.

The original facts behind this are simple enough: the rates of orgasm for each gender in different age groups, which Alfred Kinsey documented over a half-century ago. Two decades later these rates were popularized by Gail Sheehy, Shere Hite, David Reuben, USA Today, and others, narrowly interpreted into the Big Myth: that men peak sexually at age eighteen, while women peak at thirty-five. If that were true, things would be a little messy, but it would hardly be the end of the world. Unfortunately, people have worried about this ever since.

Reasonable answers to the question “when do I reach my sexual peak?” include:

• The question makes no sense.

• I know you’re concerned, but the question makes no sense.

• People never reach their sexual peak.

• It depends on what you mean.

If by “sexual peak” you mean quickness to, and hardness of, erection; and if you mean rapidity and propulsive force of ejaculation; and if you mean constantly thinking about and making dumbass jokes about sex; then, yes, many men peak around eighteen. And if by “sexual peak” you mean the age at which women are more sexually responsive and more reliably orgasmic, then, yes, many women peak around thirty-five.

But this pair of definitions is only one way to understand “sexual peak.” For example, “sexual peak” could mean the age at which people enjoy sex the most, value it the most, understand it the most, have the most experience, or use it to connect emotionally with their partner the most.

“Sexual peak” could mean the age at which people have the most spiritual experiences with sex, or find it the most psychologically comforting in the face of sorrow, pain, or fear. At the other end of the spectrum, “sexual peak” could mean the age at which some people could most easily sell their sexual services. So if we’re going to use the expression “sexual peak” (which I am certainly not encouraging), we need to define it as thoughtfully as possible, respecting our own experience and aspirations.

Let’s look at the same question in another context: sports in which people run and chase a ball, such as tennis, basketball, baseball, and football.

Virtually everyone playing these sports professionally starts playing by age fourteen. While their youthful bodies can be incredibly fit, they haven’t learned much about the game or competition by fourteen, and so there’s a limit to how well even these blindingly talented future professional athletes can play.

At twenty-four, professionals can play these sports at incredibly high levels—their bodies are fit and their knowledge is accumulating, especially if they’re well coached. At thirty-four, most athletes’ bodies have already slowed down a step—but because of their incredible experience and insight into the sport and their opponents, they can still compete at a very high level, even making their teammates better at the same time. Beyond forty-four, all the knowledge in the world can’t compensate for the slower feet, slower hands, slower eyes, or slower reactions. We almost never see someone play ball professionally at that age.

For some people, performance is so important that their skill level defines how much they can enjoy a sport. But many people find other things in sports that can be important as well—sometimes even more so. For example:

• The thrill of competition

• The familiarity of the game

• The camaraderie of teammates

• The fresh air

• Wearing the special clothes or uniform

• The sense of mastering the science and strategy of the game

• Hanging out with younger players

If you ask people who love to play sports when they’re forty or fifty or even older, most say the same thing: “It isn’t like it used to be.” Some wish it could be, while others enjoy it even better now. But they all agree, “I really like it the way it is.” In one way, they’ve all passed their peak as players. On the other hand, if they still enjoy playing way longer than they thought they would, and long after most of their peers have retired, who’s to say they’ve passed their peak?

So when do men and women reach their “sexual peak”? For people no longer interested in sex, they already did. For those still interested in sex, they haven’t yet. And if they’re fortunate, they never will.

Talking to and Teaching Your Doctor About Sex (and Your Body)

You’d be shocked to discover how little doctors learn about sex in medical school. It’s the only thing they do less than sleep.

The attitude at most medical schools is: “Let’s teach these people about important stuff, like things that will kill you (or really exotic diseases we have a big grant to study).” So your gynecologist probably knows ten times as much about cervical cancer as about sexual function. If you have cervical cancer, that’s a good thing; if not, your doctor may have trouble providing the care you actually need.

Many doctors have told me they’re concerned that if they bring up sexual topics, the patient will be offended. I generally say, “Tell them this is the high standard of care in your office, and let them be offended.” I walk this walk myself; many of my new patients are offended at my seemingly impertinent questions about sex, and my use of straightforward language to ask these questions. After a while, they generally understand my focus. Some still don’t like it, but at least they understand. I remember one patient who used to say exasperatedly, “Can’t you call it ‘down there’ like everyone else?”

In contrast, when I encourage my patients to raise sex questions with their doctors, they typically say, “Oh, my doctor would die of embarrassment if I brought up sex.” So like a bunch of nervous drivers at a four-way stop sign, everyone’s waiting for the other one to go first. You could be sitting at 6th & Main for hours.

Let’s also remember who mostly goes to medical school—people barely old enough to vote. Personally, I’m not entirely comfortable handing my prostate over to a guy who spent his Wonder Years in a library instead of learning about life; on the other hand, it beats the alternative—a doc who didn’t spend years and years in the medical school library.

I once taught sexuality to medical students at Stanford University. They were bright, earnest, and altogether the least sexually knowledgeable group of twenty-three-year-olds I’d ever met. If you’re fortunate, one of these brilliant people is now your doctor.

The moral of the story: just as you have to train your doctor about the idiosyncrasies of your skin (you burn even when it rains), your breasts (lumpy your whole life), and the rest of your body, you have to teach him or her to talk about sex with you: the sexual side effects of drugs, the contraceptive effectiveness of withdrawal, how irregular periods affect your life, questions about the safety of anal sex, why your nipples leak a bit even though you’re not pregnant, how to masturbate when you have arthritis, allergies to sperm or latex, the fact that your husband isn’t your main sex partner.

Let the docs deal with their discomfort. They’re getting paid, and it’ll benefit their personal lives.

A Personal Story

Some years ago, I injured my hand pretty badly and spent months in physical therapy. A few members of the staff were intrigued by my work, and I got to know them a little bit. To show my appreciation, one day I offered to give a lecture in the hospital. As it turned out, they were hosting an upcoming regional conference for hand injury professionals (physical and occupational therapists, sports trainers, and so on), and a speaker had just canceled. I arranged to fill in, with the topic “Sexual Issues in Hand Injuries.”

As we agreed, about a month later I showed up at the auditorium where the conference was being held. After being introduced, I looked at the two hundred people there, thanked them for the invitation, and asked, “Have you ever noticed how cranky hand injury patients are?” I got the strong positive reaction you might expect—laughing, complaining, head-shaking, swearing, people making jokes.

“Okay,” I continued, “I know you talk to these patients about everything—adapting their kitchens, their bathrooms, driving, lifting their babies. So how many of you talk to your hand injury patients about masturbation?”

It was suddenly as quiet as a country road at midnight. “Well,” I concluded, “why do you think they’re so cranky? They have trouble masturbating—some of them can’t do it for months!” Most of the group laughed and laughed; when the surprised laughter subsided, replaced by rueful recognition, I smiled. “Let’s talk about the best way to discuss sex with your patients, and why you may have overlooked the importance of the topic.”

I think a few old-timers are still talking about that presentation.

Myths About Health and Aging

Despite the enormous amount of accurate information out there and our increased access to it, there are still too many prejudices and wrong ideas circulating as fact.

So let’s end with a quiz on Myths About Sexuality, Health, and Aging.

True or False?

• Older women generally don’t climax when they have sex.

• Like younger men, older men need to climax to feel sexually satisfied.

• On the whole, older people aren’t sexual.

• Birth control pills frequently lead to cancer.

• Abortion frequently leads to depression.

• Most men who lose desire for their wives or girlfriends are deficient in testosterone.

• If you aren’t pregnant after five months of trying, you or your partner is infertile.

• Men mostly like big breasts; without them, a woman shouldn’t expect much desire from her mate.

• Most people are more sexually sophisticated when they drink.

• If a man can’t get erect, he can’t really enjoy sex.

• You can’t get pregnant the first time you have sex, or standing up, or if you douche right away.

• If a woman can’t climax from intercourse alone, sex therapy, medication, or a new partner will probably make it possible.

• Every year many older guys drop dead from too-vigorous sex—often with prostitutes or during affairs.

• Sex after the first three months of pregnancy is generally unwise.

• Most doctors know everything about sex they need to know.

• Most medications have few or no sexual side effects.

• Good-looking people are the best lovers and have the best sex.

• Erection drugs like Viagra work great for women.

• Almost all sexual “dysfunctions” can be traced to trauma, such as rape, molestation, or childhood deprivation.

• Erection problems are, of course, almost always primarily about sex.

• If you have a sexually transmitted infection (such as herpes or chlamydia), no one will want to have intercourse with you—and it’s irresponsible to even suggest it.

Answers to quiz:

All of these statements are false.

There’s nothing “controversial” about any of them.

Some people may have feelings about the facts,

but the facts are beyond question.

Regardless of gender, race, political views, or ability to make risotto, “getting older” is the one category that everyone is heading toward. (It beats the alternative, right?) For most people, aging will bring special challenges to expressing sexuality joyfully. For those who already struggle with health problems—because of pain, medication, insomnia, or disease—those challenges to meaningful sexual expression are already here.

It’s hard enough losing our cherished sources of pleasure, whether they involve food, sports, child-rearing, traveling, or sex. As we get older or struggle with health problems, it is essential that we use our Sexual Intelligence to reimagine and reinvent sex. That is how we can continue to use sexuality as a source of nourishment, rather than losing it to a narrow set of rigid definitions that inevitably exclude us.

As we have seen, however, some people are so angry or frightened about the necessity of changing their sexual vision that they refuse to do it. They gain the benefits of denial, but they pay for it in their lost sexuality. I can’t honestly say this is a mistake for everyone—only that it’s a mistake for most people. As the philosophers tell us, pain is mandatory—but suffering is optional.