CHAPTER 4

The Perils of Matchmaking

Pollination Syndromes and Plant/Pollinator Landscapes

STEVE REMEMBERS:

I scanned the hillsides above Napa Valley as we hiked along their ridges, a troupe of us trailing behind my entomology professor, Robbin Thorp, from the Davis campus of the University of California. Compared to the lower valley slopes and bottomlands where lush vineyards overwhelmed the remnant patches of natural vegetation, the hills were sparsely vegetated. High on the ridges, where shiny green serpentine rock came to the surface, the dwarf chaparral was thinner because of the witch’s brew of weird chemicals active in serpentine soils, some of which are toxic to plants.

Although many of my fellow students commented on how impoverished the plant cover was, each widely spaced shrub or tree could be seen and smelled for its uniqueness: digger pine, Sargent cypress, the localized form of manzanita. This advantage was not lost on me. I was working at learning both the flora and the fauna of the Inner Coast Range along the continent’s edge. I asked Robbin to point out any plants he noticed that were unique to the area.

About that time, a strong and unusual fragrance made me stop dead in my tracks. Although miles above any winery, I recognized the fragrance as virtually the same as the bouquet from an estate-bottled Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon I had recently tasted and enjoyed. Looking around, I realized that the aroma could only be coming from one place—the dark maroon flowers of the large-leaved bush alongside the trail. Not just any bush; but the western spicebush, known to botanists as Calycanthus occidentalis.

Even as I enjoy a glass of tannin-rich wine today, I remember the flash of olfactory recognition that leapt through my head the moment I smelled the spicebush: “Beetles. It must be pollinated by sex-starved sap beetles!” Without having seen the pollinators, I had predicted—simply by cues of floral color and fragrance—at least one of the animal groups that might be transferring pollen between plants of the western spicebush in these Napa foothills.

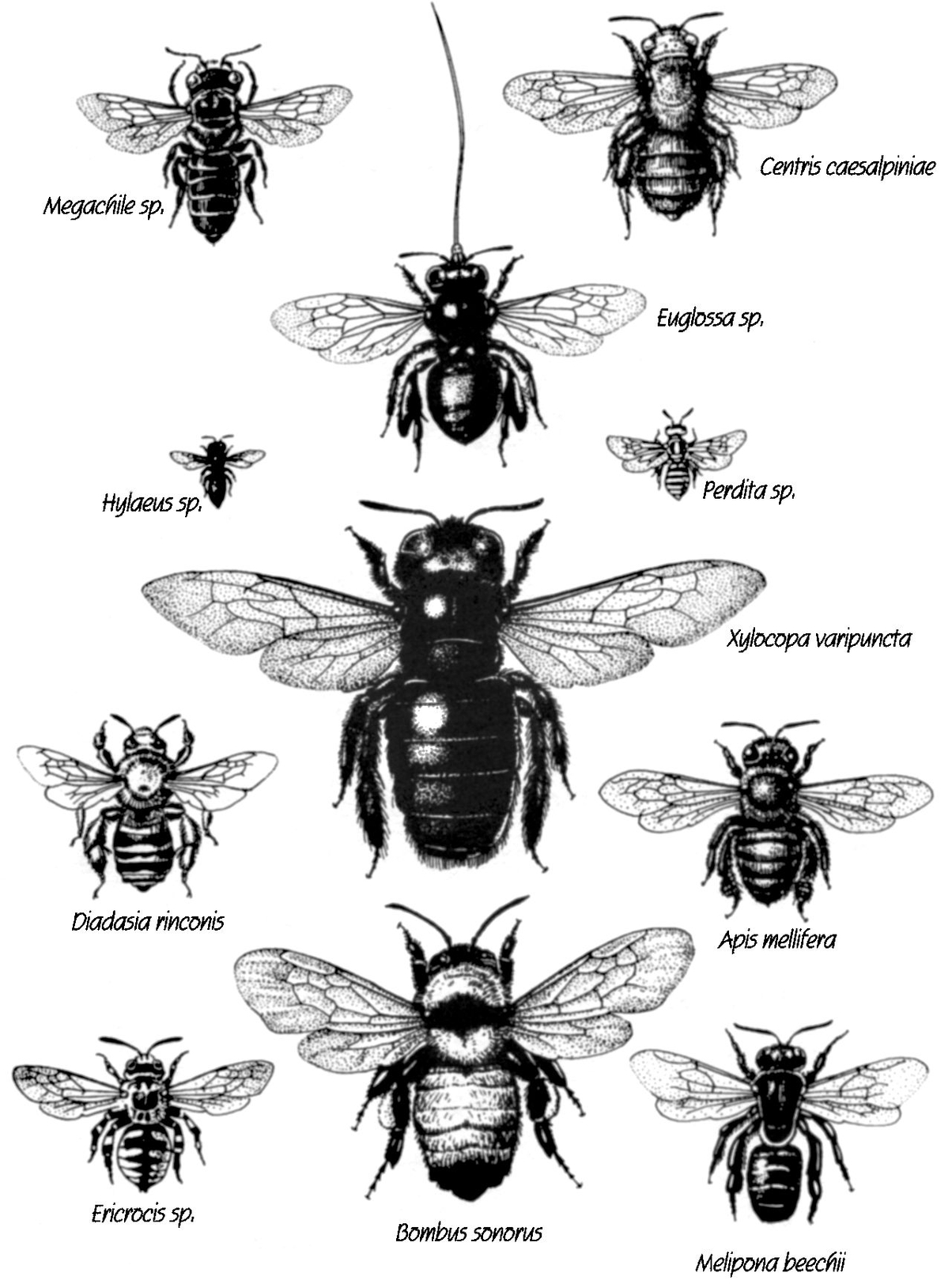

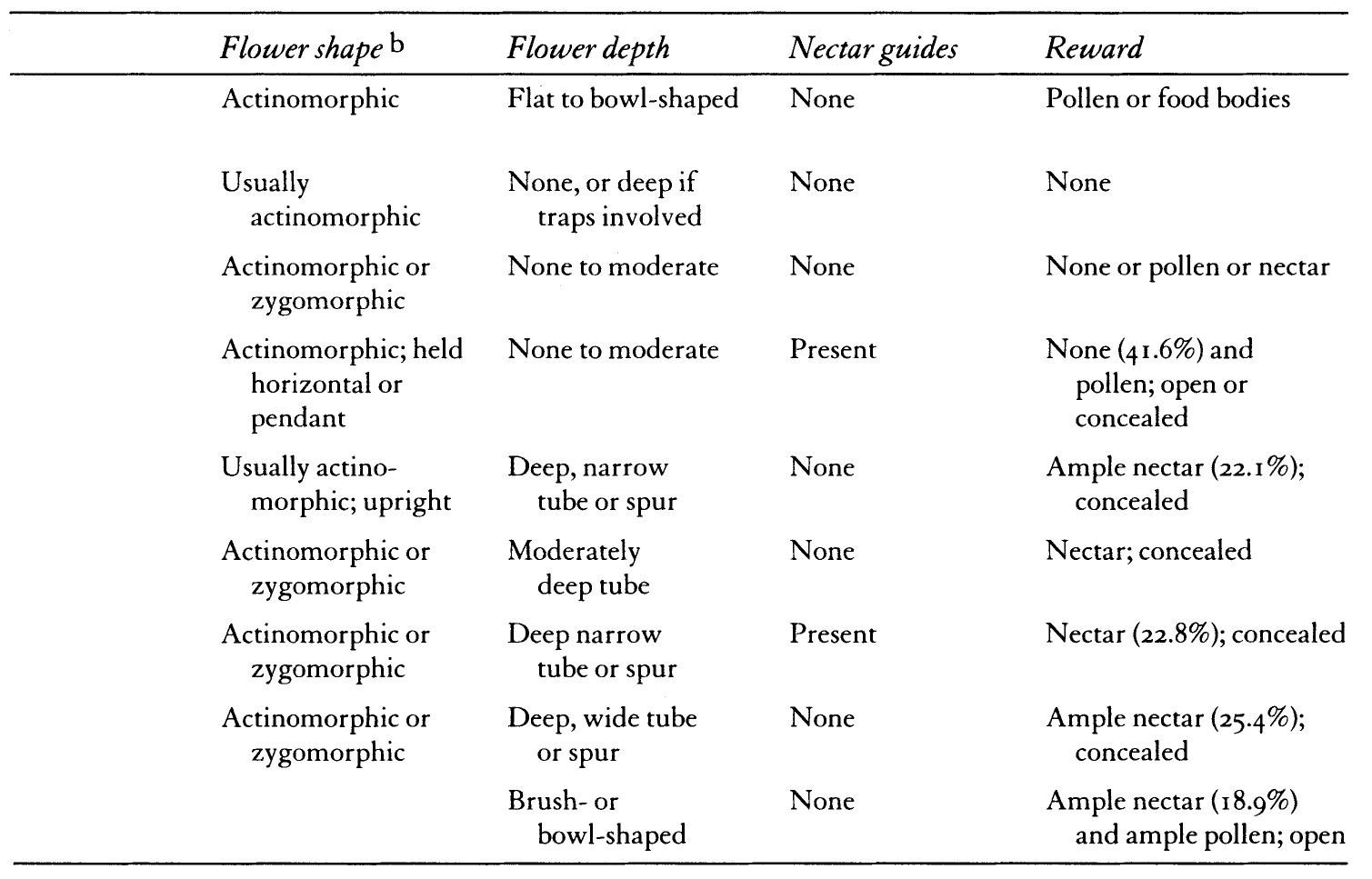

TABLE I: Pollinator Syndromes

This guessing game is one that has both intrigued and aggravated biologists for much of this century: to what extent is it possible to deduce the animal pollinators of a certain kind of plant simply by knowing key characteristics of blossom and creature beforehand? The interacting set of plant and animal attributes that form a consistent pattern is known as a pollinator syndrome. (Table I). As we shall see, this routine of pattern recognition, like any guessing game, can be great fun, but it often underestimates the complexity and variability of relationships found in nature. Some biologists today are forsaking this game of identifying “classical relationships” for another, more difficult one. Because this newer game requires more empirical observations of pollinator foraging and flowering patterns of all the plants in a particular landscape, it better approximates the diversity of plant/pollinator interactions.

This novel paradigm, recently proposed by ecologist Judith Bronstein, allows us to identify plant/pollinator landscapes. These landscape patterns inform us not only of the interaction between beetle and spicebush, but all the other flowers that beetles sequentially visit and all the other animals that visit spicebushes and their neighbors. Like a basic ground rule in the pollination syndrome game, this one also assumes there are key traits of flowering plants and pollinators that do not vary independently, but cluster together in space and in time. But unlike another assumption in the pollination syndrome game, we now recognize that such traits vary both within and between species. Not every spicebush population may flower at the same time, nor attract the same beetles. Likewise, some beetles may actively pollinate spicebushes, while others may only visit them infrequently, preferring to concentrate their activities on other neighboring plants. To play either game, we must learn which floral traits matter to pollinators and which features of animals have shaped flower morphology and phenology over evolutionary time. To highlight some of these traits, let’s return to the spicebush.

Looking at the maroon blossoms of the spicebush more closely, we begin to note clues that they could indeed be beetle blossoms. The flowers are about an inch and a half long, formed by fleshy, almost succulent tepals—a fusion of the corolla’s petals and the sepals of the calyx—that protect the rewards within. They produce no nectar but are loaded with bright yellow, rather oily, pollen grains. And on the tips of each of the innermost reddish tepals, we encounter rough white “food bodies” containing what is known as tubular pollen. Such food bodies are found within many primitive flowers, supposedly to hold the gustatory interest of beetles so they do less damage to tender plant parts as they seek protein-rich pollen upon which to dine. Held within the protective flower, beyond the reach of most predators, beetles also engage in frequent copulations with others of their kind.

These floral traits are reminiscent of the primitive flowering plants of New Guinea and New Caledonia, which have been studied as “living fossils” to reconstruct the conditions under which animal pollination first evolved. Such flowers either have sweet, spicy fragrances or strong, unpleasant ones—smelling like rotting tropical fruit or, worse, a pair of neglected dirty sweat socks returning from summer camp. There is one tree species in Guanacaste province of Costa Rica—Sapranthus palanga—that students have dubbed the “thousand-dirty-sock-tree.” In either case, these open-cupped blossoms offer a number of attractants (such as fragrances) and rewards (oily yellow pollen and whitish food bodies) that beetles and flies can both perceive and handle. When beetles feed on spicebush pollen, some of it sticks to their hard cuticles. Later, when the beetles move to feed on another plant, it gets passively transferred to floral parts (including sexually receptive stigmas) in other flowers.

In the hills of California’s Napa valley grows the western spicebush (Calycanthus occidentalis). The large flowers have many primitive features including numerous parts, fleshy tepals, and white food bodies. The floral aroma is reminiscent of a blend of overripe fruit and cabernet sauvignon wine. Dozens of nitidulid and staphylinid beetles are attracted to these flowers as pollinators.

Beetles, however, do not always make the most effective pollinators. In fact, they blissfully browse on various flowers, many of which they never pollinate. For certain species like the spicebush, they do transport pollen in their search for more white food bodies and mates. But often they drop more pollen when they are walking between plants than they deliver to another flower. Furthermore, if another spicy species forms a local attraction, they may immediately zip over to browse there without ever delivering pollen to a compatible flower of the first species.

This sort of casual pollen transfer by beetles has been termed mess-and-soil pollination by floral biologists because these insects tend to eat and defecate their way through such blossoms. A single kind of flower is seldom, if ever, dependent on just one kind of beetle. The roving beetles, in turn, are hardly ever attracted to just one species’ scent in their neighborhood. The mutualism is loose, diffuse, if you can call this relationship a mutualism at all. And yet it has become customary for ecologists conversant with the pollination syndrome game to refer to spicebush blossoms as “beetle flowers.” The gangly blooms of ocotillos are known as “hummingbird flowers,” and the white trumpets of night-blooming cereus as “hawkmoth flowers,” even though scientists have recorded other animals pollinating or at least visiting and feeding among these blossoms.

This matching of blossom types with guilds of similar flower-feeding animals appears to be a universal pastime among humans. Just like players of the pollination syndrome game, many indigenous cultures assume that closely related animal visitors visit particular shapes of flowers, to feed upon their honeylike nectar. Ecologists have simply refined this folklore by acknowledging the many floral resources that attract animals, as well as the many animal adaptations to floral forms. Butterflies and moths, for example, use coiled strawlike proboscides to sip nectar lying at the bottom of deep floral tubes.

It did not take curious naturalists long before they began to associate lepidopteran feeding behavior with certain shapes, colors, and sizes of flowers. Many languages have names for plants that essentially mean “butterfly-weed”—as is the case for a milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, in temperate North America. Monarch and queen butterflies are among the many that frequent this orange-flowered perennial throughout its range. Vernacular Spanish lexicons from Latin America contain some wonderful associations between flower and pollinator, in which both are known by the same folk name. For example, chuparosa (“rose-sucker”) refers not only to a hummingbird but to a red, tubular flower such as Justicia californica as well. It is true that hummingbirds in the Americas actively seek out tubular flowers that are often red or orange in color and rich in nectar. Hummingbirds learn that red signals the possible presence of nectar nearby. In fact, this color stimulus is so strong for hummingbirds that if you put on lipstick, fill your pursed mouth with wine, and stand where crimson-colored sugar feeders or potted magenta flowers have been outside, the hummingbirds will often feed right out of your mouth.

The premise that certain guilds of animals have strong allegiances to particular floral classes was first formally outlined by Frederico Delpino, a naturalist from Milan, in a series of papers published between 1868 and 1875. Paul Knuth, another giant in floral biology, is often credited for codifying pollination syndromes around 1910. These syndromes were later refined and amplified by the great German pollination biologist, Stefan Vogel, in a seminal essay published in 1954. In that essay, Vogel suggested that by recognizing certain patterns that he called Stil (“style”), floral biologists could predict which blossom visitors might be legitimate pollinators. Whether studied in the field or in the herbarium, Vogel argued that anyone could see how floral forms were suggestive of harmonious relationships with particular animals. And his essay illustrated these pollination syndromes with such beautiful plates that each relationship quickly became a truism in biological literature. To his credit, Vogel did caution his readers that such syndromes should be considered working hypotheses to be tested in the field. Nevertheless, other scientists took the color plates illustrating Vogel’s classification at face value. For the two decades following his 1954 publication, biologists turned pollination syndromes into stereotypes, as if one-to-one relationships between plants and pollinators were the norm in the natural world.

Vogel’s influence on correcting these simplifications was somewhat muted, for his publications appeared only in German. Other pioneering scientists such as Christian Sprengel, Paul Knuth, and Herman Mueller helped to establish the use of syndromes as a teaching tool in modern studies of floral biology, but their caveats were not heeded in more popular accounts. By the time Knut Faegri and Leendert van der Pijl’s classic textbook The Principles of Pollination Ecology was published in 1979, the pollination syndrome was well established as the prevailing paradigm for studying the interactions between flowers and their pollinators. Although early workers intended that the concept be used experimentally, flexibly, it somehow became codified into dogma in the modern botanical literature. Too many traveling biologists became preoccupied with looking at the pollination syndrome classificatory approach as a fully explanatory signpost, and forgot to look for other signs and where they were pointing. Nevertheless, we believe that this methodology can still be used as an invaluable heuristic tool by students, naturalists, and biologists who aren’t pollination biologists per se.

Certain floral shapes, fragrances, nutritional rewards, and blossom opening times became tightly linked to the evolutionary influences of a single species of beetle, bee, or bat. The lexicon for these “animal-loving flowers” currently in vogue among some biologists—cantharophily, melittophily, chiropterophily—is an outgrowth of earlier classification systems. Herbert Baker and colleagues elaborated these classifications to take into account not only floral morphology but nectar and pollen chemistry as well.

We know now that many of these interactions are not simple stories of intimate one-on-one relationships. In fact, University of California ecologist Nickolas Waser first encountered difficulties using such projections when he tried to explain the flowering times and seed set of the ocotillo’s “hummingbird flowers” by the timing of hummingbird migrations through the arid Southwest. Waser and others were surprised to find that in many ocotillo stands, the red tubular flowers are nectar-robbed or pollinated by carpenter bees more often than by birds. Later in the summer, while desert bees are pollinating “hummingbird flowers,” the same hummingbird that passed through the desert two weeks late for ocotillo may be pollinating 13 different kinds of alpine meadow plants, representing eight distinct plant families and several syndromes.

Studies by Liz Slauson of the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix, Arizona, on the floral biology and pollination of Palmer’s agave (Agave palmeri) have also revealed a complex story of floral adaptations and guilds of primary and secondary pollinators. These massive century plants use a “big bang” reproductive strategy—that is, they bloom just once after storing up food reserves for decades, then the individual plant dies while its genes are carried into the next generation within the seeds shaken from the fruits. Their flowering stalks appear like ornate candelabras punctuating the fiery Arizona summer skies during sunset.

Although the flower stalk architecture is clearly modified (open and sturdy flower clusters presented on short horizontal branches), when night’s darkness gives way to the chill of dawn, other interlopers are on the scene. At this time of the early morning, one can see and hear clouds of hungry bumblebees, honeybees, and carpenter bees along with paper wasps and giant orange and black tarantula hawk wasps. They greedily slurp up the bonanza of nectar and the female bees carry off the pollen. This is so because even in a site rich with local bats there is an overabundance of floral goodies for all the players. But, as mentioned earlier, many sites are without the migratory nectar corridor-tracking bats or their numbers are much reduced due to bat roost destruction within caves or pesticide poisoning. Liz has determined that when bats are indeed scarce, the early morning bees get much of the agave pollen and nectar. Fortunately for Arizona century plants, bees are quite successful in pollinating the agave blossoms even though their floral evolution was most likely shaped by dancing with bats.

Elsewhere, in the lowland tropical forests, a single euglossine bee species may visit up to eight different kinds of orchids that flower sequentially in their Panamanian habitat. Waser and his colleague Mary Price have concluded that “generalization appears to be the rule among pollinators”—adding that for the various plants visited by hummingbirds at a particular site, “most of the flowers do not conform to a ‘bird pollination syndrome.’”

Why then have some ecologists continued to use pollination syndromes as a tool for teaching about plant/animal interactions? The answer is simple. The syndrome game remains helpful as a point of departure when little is known about a plant’s floral visitors. It may not suggest the entire range of animals to look for as potential pollinators, but it will help deduce a few of them. The pollination syndromes approach can still be used to advantage by students and other newcomers to the pollination game.

In some cases, we can only infer what the historic relationships between a plant and its predominant pollinators might have been, for these mutualisms have been profoundly disrupted by changes in the modern landscape. Such a deductive approach is routinely used by biologists visiting habitat fragments where only generalist pollinators such as honeybees persist. Floral morphology and nectar chemistry, for example, can be used to predict the historical presence of a pollinator—if that pollinator was singularly important in shaping the evolution of the plant’s floral characteristics. And even though a plant may have gone extinct before its pollination ecology was adequately studied, the animals that once visited it may still show signs of adaptation to its kind of flowers. Moreover, certain inferences drawn from present-day fauna and from historic specimens may be used to confirm what the original interaction between plant and pollinator was like.

There are some remarkable cases of ecological detective work that resulted in the identification of pollinators other than those found visiting the plant today. In one case, plant ecologist Paul Cox was skeptical when he read secondhand accounts of rats pollinating an indigenous Hawaiian vine known as the ieie, Freycinetia arborea. It had few characteristics of a plant pollinated by nonflying mammals. He decided, therefore, to spend four days in a blind where some of the vines grew in forests above Kealakekua, Hawaii. During that time, he saw no rats on the plants and identified only one regular visitor to ieie flowers—a bird known as the Japanese white-eye. But the white-eye was first introduced to Hawaii from Japan in 1929, so its recent role in pollination of ieie flowers could not account for certain characteristics of the plant’s inflorescences. The female flowering stalks of the ieie are rich in hexose sugars and certain amino acids that have independently evolved in the flowers of many plants attractive both to perching birds and to bats. Cox sensed that other birds must have been hidden in the history of the ieie vine.

Checking thousands of pages of Hawaiian naturalists’ journals from the nineteenth century, Cox encountered notes suggesting that the islands were once visited by several birds that are now endangered or extinct: the Hawaiian crow, the oue, and a crossbill-like bird, last seen in 1894, that once lived on the Kona Coast. Cox took early museum specimens of these birds and began to examine their head feathers with a scanning electron microscope, searching for pollen grains. To the astonishment of his colleagues, Cox discovered dense quantities of a distinctive pollen type on the head feathers of the oue and Kona crossbill specimens and moderate loads of the same pollen on the head feathers of the Hawaiian crow. These pollen grains looked identical to those he obtained from a 57-year-old specimen of the ieie vine. Apparently these three birds regularly dipped their heads in the floral bracts of male ieie vines, and no doubt visited female flower stalks for other rewards as well. Cox’s doubts were well founded: there was nothing about ieie flowers that suggested adaptations to rat pollination; in fact, that earlier claim was based on an error that had been magnified through repeated elaborations over the years. Instead, Cox proposed, the ieie flower stalk evolved for accessibility to a variety of birds, ranging in size from the introduced white-eye (a 4-inch-long bird) to the rare Hawaiian crow (almost 20 inches in length). The oue, the Hawaiian crow, and the Kona crossbill had all nearly gone extinct before the end of the nineteenth century, so the ieie must have suffered low pollination levels and seed set declines for a while. Nevertheless, these perennial vines could have persisted because they can vigorously reproduce by branching and re-rooting. By the late 1930s, the introduced Japanese white-eyes had probably begun to take over pollination of the vine. Seed set no doubt rose again.

In another widely heralded case from Hawaii, a large number of “cardinal flowers” in the Lobeliaceae family have suffered extinctions in the last century, forcing their coadapted pollinators to shift to other floral resources. Of some 273 lobelioid species, subspecies, and varieties historically described from the Hawaiian Islands, only 27 percent have sizable enough populations to keep them from immediate extinction. A quarter of the species have gone extinct within the last century; another 19 percent of the species, subspecies, and varieties may be considered rare or endangered. This catastrophic decline in Hawaii’s largest plant family poses the question: what has happened to their coevolved pollinators? For years, biologists had speculated that a number of Hawaiian birds known as honeycreepers may have coevolved with lobelioids, for some of them have long, downwardly curved bills that match the shape of floral tubes of certain cardinal flowers.

But when biologist Coleen Cory went searching for honeycreepers visiting the flowers of two rare lobelioids in the Koolau Range on Oahu, she failed to record a single bird on these plants during 136 hours of observation. A few hawkmoths, small black bees (the endemic bee genus Hylaeus, a colletid), and introduced honeybees were the only floral visitors she recorded on either lobelioid. She also found that these two rare plants are now capable of self-fertilization: they may not require birds or any other animal to move pollen from plant to plant in order to set seeds. Cory concluded that mutual codependence between honeycreepers and lobelioids was insupportable on the basis of present-day observations of both organisms on Oahu.

Recently, though, a team of zoologists has come to a different conclusion, arguing that the characteristics of living organisms cannot be understood in terms of modern conditions alone. When Thomas Smith, Leonard Freed, and colleagues looked at historic museum specimens of one Hawaiian honeycreeper, the i‘iwi, they found that its bill was longer in the nineteenth century than it is today. Then they discovered a handful of historic notes from the nineteenth century. These notes documented i’iwi honeycreepers feeding on now rare or extinct lobelioids with long, tubular flowers that produced copious, hexose-rich nectar but no odor—floral traits that fit birds, rather than the insects Cory recorded. A long bill would have served the i’iwi honeycreeper well when these flowers were more abundant.

Most i‘iwis have been observed feeding on the open flowers of the ohia lehua (Metrosideros) tree, one that lacks tubular corollas specifically adapted to birds. Smith, Freed, and coworkers hypothesize that as the lobelioids declined in the nineteenth century, the once-common i‘iwi honeycreepers began shifting to other floral resources in order to survive. Honeycreepers need no special bill adaptations to obtain nectar from ohia flowers. The zoologists suggest that the dietary shift from tubular flowers to open flowers resulted in directional selection for shorter bills. In other words: the i’iwis with the longest, most downward-curving bills were lost from breeding populations over the last hundred generations. The upper bills of i‘iwis today are 2 to 3 percent shorter than those of i’iwis collected before 1902, when lobelioids were still quite common in the forests.

The nearly extinct i’iwi honeycreeper (Vestaria coccinea),from the Hawaiian archipelago, is the only known pollinator of several endemic flowers such as this Clermontia species. Its highly curved bill allows it to remove nectar efficiently from the similarly curved blossoms.

Such examples suggest that there are indeed long-term matches made between sets of pollinators and particular plants, but these matches are seldom so exclusive or inflexible that other organisms are permanently left out of the picture—whether those “others” are Japanese white-eyes or Hawaiian ohia trees. Unfortunately, many historic ecological studies tend to leave these other organisms out of the picture they frame by the way their goals are delineated. To overcome this tendency to look only at plant/animal pairs—rather than the entire interplay of floral resources and pollinators in a habitat—Judith Bronstein has encouraged us to take a step back and look at the entire landscape of ecological interactions revolving around pollen and nectar availability.

Admittedly Bronstein, like others before her, concedes that “we know remarkably little about how pollinators respond to the spatial and temporal variation in their floral resources.” We do know that pollinators commonly move among patches of floral resources as they forage. And yet we seldom know how far they travel to make ends meet during a single day, let alone the distances they travel for food in their entire lifespan. Botanists at Barro Colorado Island, La Selva, and Monteverde in Costa Rica are among the few that have recorded exactly how many plant species are competing for the same pollinators in a given landscape—or, conversely, how plants have been selected to flower at different times and intensities to minimize competition with one another.

The most complete survey we know is a 50-month study of the insects that work the 133 kinds of plants found on 80 acres of Greek phrygana, a heavily grazed and burnt Mediterranean ecosystem of herbs and shrubs near Athens. In this disturbed community, which few ecologists would predict to be particularly rich, Petanidou and Ellis have documented the highest pollinator diversity yet recorded: an astonishing 666 species of insects, including over 225 species of solitary bees. Oddly, the climate is so variable at this site that only 20 percent of the entire pollinating fauna has been found present in all five years of the study. No bats or birds have been recorded in the area. But each flower in the phrygana averages five kinds of insect visitors, be they wasps, bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, or flies.

Gradually, Bronstein and others have begun to integrate various studies such as the Greek phrygana effort to give us an expanded view of plant/pollinator landscapes. Although additional studies now under way will add color and depth of field to these pictures, a few of these patterns can be illustrated here in a preliminary way. The first kind of landscape is dominated by generalist pollinators associated with flowers that bloom sequentially or without overlap. This kind of landscape is very common in the tropics, but it can also occur in highly seasonal environments all the way to the Arctic tundra. In tundra and in the wet tropics, the flowering times of a number of plants in the same habitat are complementary and do not necessarily compete for the same pollinators. In addition, the same plant may be visited by a sequence of pollinators over a long flowering season. For instance, lavender in southern Spain is visited by 70 different kinds of bees, butterflies, and moths, each with a different peak period of activity over a three-month blooming season.

At the Rocky Mountain Field Station in Colorado, Leslie Real and Nick Waser found evidence of sequential mutualisms: Flowering larkspurs supported hummingbirds soon after their arrival in the mountain meadows. The hummingbirds subsequently pollinated the late-flowering trumpets of Ipomopsis. Wherever these two flowers were found together, they were visited by the same sets of hummingbird species, but showed low levels of flowering overlap. On the floodplains of western Colorado below the Rocky Mountain Field Station, however, the Ute ladies’ tress orchid demonstrates the perils of sequential mutualisms. Sedonia Sipes and Vince Tepedino have shown that because bumblebees rely on this rare orchid only for nectar, a sequence of other flowers must be available to provide it with pollen over the entire season. Lacking these foraging resources in the area, not enough bumblebees will stay to cross-pollinate the little orchid. Consequently, the presence of other species providing additional pollen sources for bumblebees may be just as critical as the pollinators themselves for the orchid.

Another example of this first landscape was recently described in forest fragments in Japan, where bumblebees sequentially visit a number of obligately outcrossing flowers over the span of a season. The earliest herb flowered in April, but did not have a good seed set, particularly where the forest fragments were found in residential areas. It appears that the season’s bumblebee colonies had not yet grown large enough to service areas where there were insufficient flowers to attract them. When June came along, and the next herb flowered, there were ample rewards for bumblebees in the forest islands within agricultural and residential areas; the second herb had a high seed set in both areas. The third perennial herb flowered in August, and it too was not limited by pollinators.

The second kind of plant/pollinator landscape is dominated by generalist pollinators of plants that bloom all at the same time. This pattern often occurs in deserts and subtropical habitats where plants respond in concert to one brief rainy season, but it may be common in temperate and alpine zones as well. Plants in these landscapes are clearly competing for pollinators. And each may suffer low reproductive success, because bees or butterflies there may move indiscriminately from one species to the next, wasting pollen along the way. Some tropical herbs such as Calathea occidentalis produce unusually luxuriant floral shows to compete for the most effective pollinators, which in this case are bees that are seldom very abundant. More common butterfly visitors are far less reliable in moving pollen from one Calathea to the next, yet they clearly benefit from abundant nectar associated with these mixed species shows. Spring wildflowers along the Sicilian coast show a similar tendency toward profuse simultaneous blooms that attract a wide range of insect pollinators.

The third landscape pattern is dominated by specialist pollinators that visit plants having prolonged periods of flowering in an environment without seasons. Short-lived wasps, for example, must find a sequence of fig trees of the right species flowering in their local environment year-round, or else they will go extinct. Fortunately for the wasps, few fig trees in the same population flower at the same time.

In the fourth plant/pollinator landscape, generalist migratory pollinators such as nectarivorous bats switch through a variety of nectar-providing plants as they migrate from tropical to arid temperate environments. Even where there is only one nectar source available for a particular bat species, it usually flowers in sequence with other bat-loving plants to the north and south, along the bat’s migratory route. Thus the bat may specialize on just one kind of flower in each local environment, but these are linked into a nectar corridor of successive flowering times along the bat’s migration route.

This concept of a nectar corridor for migrants, roughed out by Donna Howell in National Geographic Research in the mid-1970s, has recently been fully articulated and elaborated by Ted Fleming. His work has focused on the geographic sequence of plants used by lesser long-nosed bats—one of several pollinators of giant columnar cacti, century plants, and manfredas. These bats tend to utilize nectar from century plants in late fall and early spring and nectar from tree morning glories in the winter. In the summer, when they move great distances every month, they apparently seek out densely blooming patches of various century plants and columnar cactus species, foraging as much as 60 miles away from their day roosts. The migration of hummingbirds from northern Mexico through the Southwest over a monthlong period each spring apparently matches a similar sequence of flowering from south to north of various ocotillo species and populations. We have accompanied Ted on some of his nocturnal sojourns to the land of cardón and saguaro cacti alongside the Sea of Cortez near Bahia Kino in search of nectar-slurping migratory bats. Although bats are not the exclusive pollinators of either the giant columnar cacti or nearby century plants—remember, as Liz Slauson showed, that they can be adequately pollinated by bees and wasps in the morning after the blooms open—they do in fact appear to be pollen-limited at some sites and especially during years when bats are rare and visits to the flowers are infrequent.

The final landscape described by Bronstein is fairly rare: it is dominated by specialist pollinators, each associated with a small set of plants that flower at the same time. This landscape can be found in deserts, seasonal subtropical scrub, or alpine tundra. There we find dominance by oligolectic solitary ground-nesting bees, linked to a single widespread dominant plant such as creosote or mesquite, or moths that specialize in just one local yucca. Such insect specialists face serious problems if they emerge before or after the flowering of their sole set of floral resources—if late snows kill the earliest flowers, for example, or even postpone the entire flowering season. It can also occur in deserts following warm, frost-free winters that encourage the early opening of floral buds, weeks before migrating pollinators arrive. This is one more landscape where the perils of matchmaking are all too evident. Yuccas and yucca moths form one of the obligatory partnerships that occur between specialist pollinators and synchronous flowerers—and so they are vulnerable to a variety of destabilizing forces. It is no wonder that such one-on-one relationships comprise less than I percent of all observed plant/pollinator interactions in the environments that have been intensively surveyed.

But other plant/pollinator landscapes can become just as vulnerable as those with pollinators that specialize on synchronously flowering plants. If a specialist or a generalist dependent on sequential flowering of several species finds that one link in its chain is broken—through habitat destruction, say, or selective removal of the plant forming the most critical link—it may be unable to wait without food until other resources become available. In short, even pollinators that do not show strict dependence on a single flower may become vulnerable due to their dependence on a short list of floral resources.

More than 20 years ago, eminent tropical ecologist Dan Janzen became concerned with the vulnerabilities of such interactions as the dry subtropics of Costa Rica became more and more fragmented into a jumbled patchwork along the Pan American Highway. Janzen wrote prophetically about the perils to be faced by traplining hummingbirds that must forage along a 10-to-12-mile route through dry forest every day to obtain sufficient food for themselves and their young. When a significant portion of forest along their trapline is logged or converted to pasture, the entire trapline becomes worthless. Janzen wrote: “What escapes the eye . . . is a much more insidious kind of extinction: the extinction of ecological interactions.”

While the few documented cases of truly obligate pollinators and synchronous flowers remain especially vulnerable, the other three plant/pollinator landscapes can also suffer from the extinction of mutualistic relationships. Yet each will occur according to its own pattern and at its own pace. It is easier to predict linked extinctions for strict mutualists which lack Japanese white-eyes or Ohia lehua trees to catch them in their fall toward extinction. However, other kinds of relationships can be profoundly disrupted as well. Just as we are beginning to turn our attention to plant/pollinator landscapes in their entirety, we are realizing that the big picture is rapidly becoming cracked, fissured, or torn to shreds.

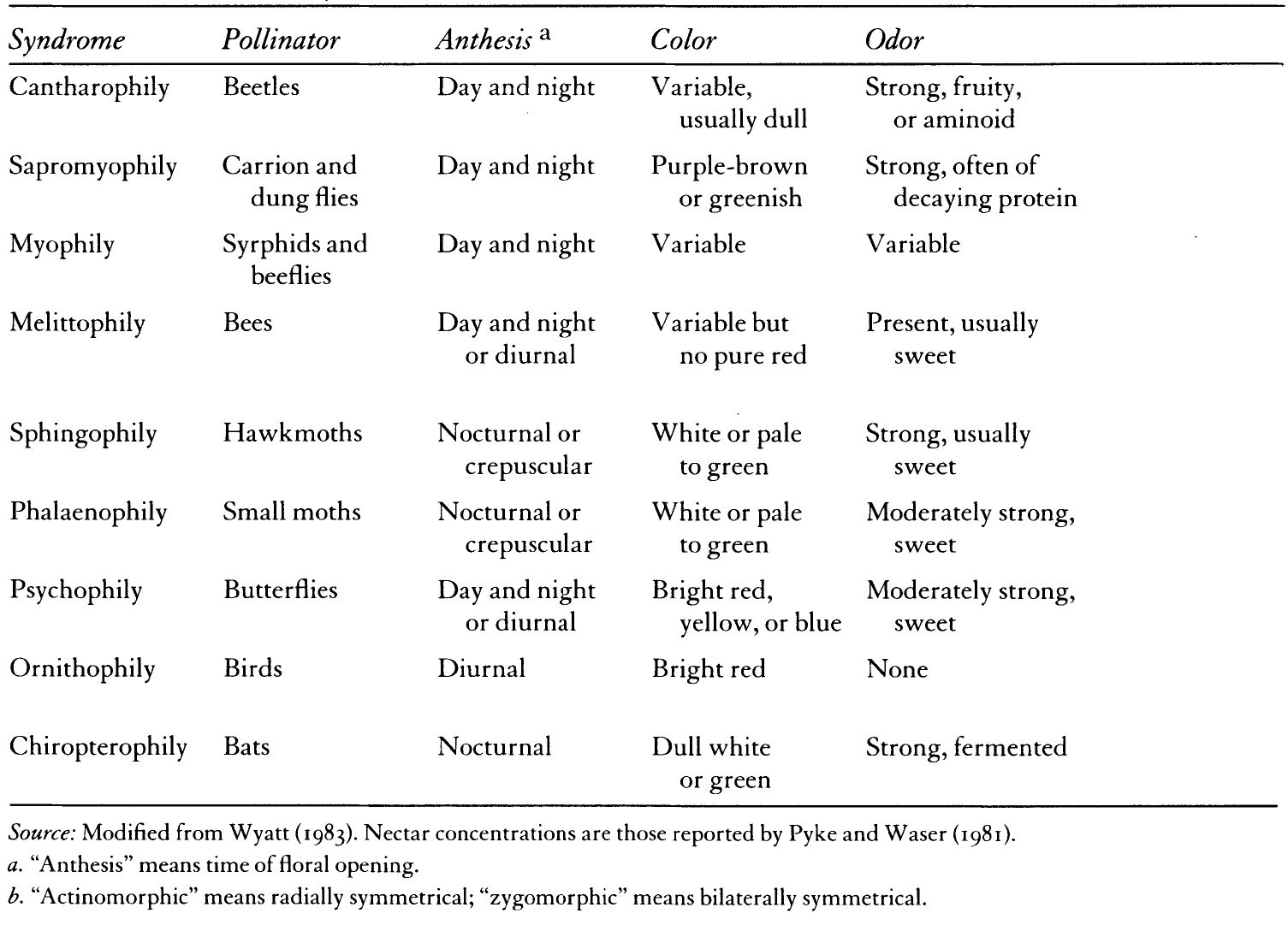

Bees come in all shapes and sizes, as shown in this selection of II species from the tiny Perdita to the giant carpenter bee (Xylocopa) in the center. Note the extremely long proboscis on the orchid bee (Euglossa) and the pollen loads on the bumblebee (Bombus sonorus). The bees are shown here approximately twice their actual size.