13

Fiduciary Responsibility

Introduction

AS MY OWN relationships with various public pension trustees developed over time, often frequently veering more toward the personal, one topic in particular would come up: the critical issue of trustee responsibility and liability. In fact, one trustee bluntly suggested the full title of this chapter should be “Fiduciary Responsibility: How Not to Get Sued.” Most public pension trustees do not have formal legal training. As Chapter 11 highlighted, only 20% of public pension trustees at even the largest pensions in the United States have legal backgrounds. Every trustee willingly accepts their role knowing that they will be legally liable for failing to fulfill his or her fiduciary responsibility. Yet most trustees assume their role without a clear understanding of what fiduciary responsibility actually means.

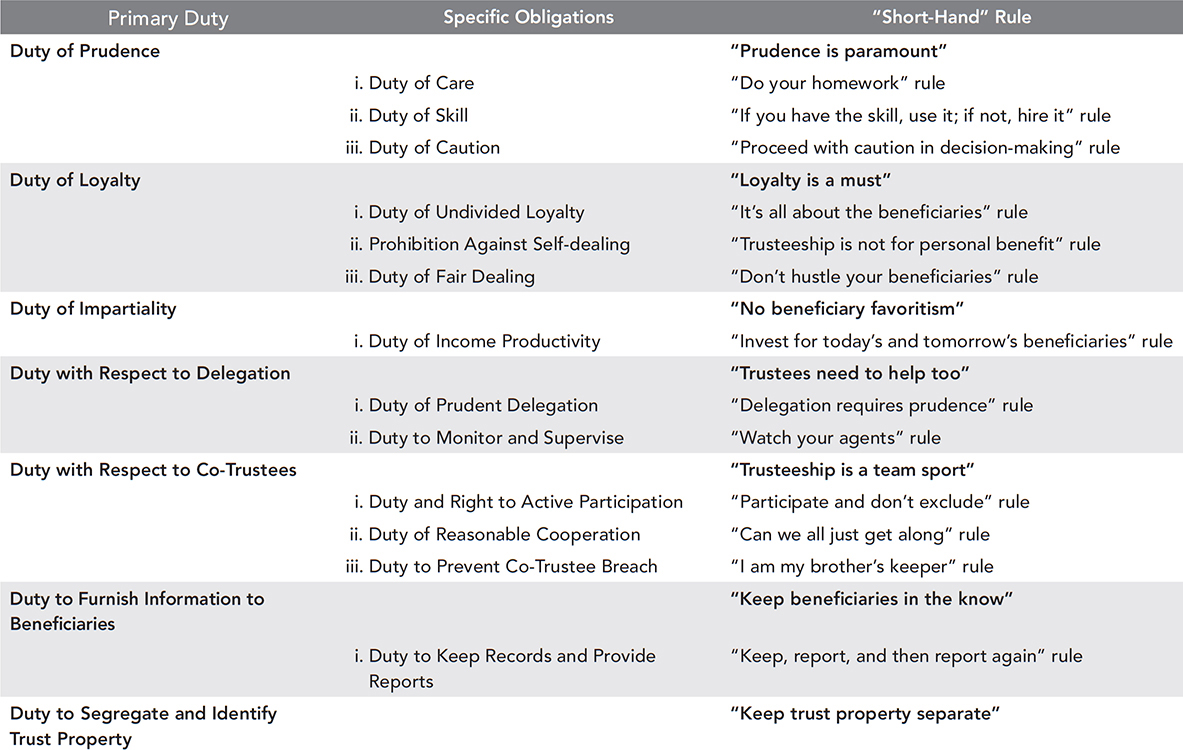

Few trustees are given a practical, legal overview of their fiduciary responsibility. This chapter is meant to be just that useful overview. Chapter 12 will provide both a brief background on the law governing public pensions and a review of the specific duties that, in sum, make up a public pension trustee’s fiduciary responsibility. The seven core duties are (1) prudence, (2) loyalty, (3) impartiality, (4) respect for delegation, (5) respect for co-trustees, (6) required information disclosure to beneficiaries, and (7) the segregation and identification of trust property. My hope is that by systematically breaking down these core duties, the idea of fiduciary responsibility will change from a murky “concept” to usable rule to govern day-to-day public pension trustee decision-making and conduct.

ERISA Exemption and Relevance

In the United States public and private pension plans are structurally regulated very differently in form. In practice, however, the legal framework governing public and private pension fiduciaries is similar. The Federal Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) governs private and federal pensions in the United States.1 ERISA does not require any private employer to establish a pension for its employees. However, if a private corporate entity does establish a pension, ERISA requires that the pension must meet certain minimum standards. Title I of ERISA prescribes standards for plan participation, vesting, funding, fiduciary duties, disclosure, and reporting.2

Historically, public pension plans were exempted from ERISA for two reasons. The first touched upon basic state budgetary concerns and the politics of the 1970s. While ERISA legislation was being debated and negotiated in Congress, the determination was made to exclude governmental retirement plans from the major provisions of ERISA pending further study.3 The House of Representatives’ Committee on Education and Labor eventually issued its finding on the issue in 1978. The committee’s Pension Task Force estimated that close to half of the defined benefit plans in the public sector were funded in ways that had nothing to do with their accrued pension liabilities.4 The task force found that 42% of public pensions used either pay-as-you-go methods or some other nonactuarial method, such as matching of employee contributions. If ERISA-like funding requirements were imposed on public plans, many of these state and local governments would have to raise their contributions by more than 100%, and a few by more than 400%.5 Very few legislators had the political capital or courage to impose such contribution increases on already typically stretched state and local budgets. As a result, the 1978 bill entitled the Public Employment Income Security Act of 1978, though introduced in the House of Representatives, ultimately failed to pass.

The second reason public pensions are exempt from ERISA relates back to the more fundamental constitutional issue of state’s rights.6 Since the formation of the United States, individual states have always been very sensitive to the ability of the federal government to require or, in turn, limit their activity. The possibility of the federal government requiring state and local governments to dramatically increase their pension contributions to meet ERISA-like funding requirements clearly hit this nerve. State and local governments reacted accordingly, rejecting this imposition. However, with the lack of federal guidance, state and local governments filled this void with their own laws and regulations that included a combination of state constitutional law, state statutes, and evolving case law. In aggregate, this combination is substantially similar to ERISA in terms of the protection of plan participant benefits, vesting requirements, financial reporting, and standards of fiduciary responsibility.7 In fact, “whenever possible, the practice in the public sector is compared to the standards of ERISA.”8

Therefore, to understand a public pension trustee’s fiduciary responsibility (and to begin to address the question of “how not to get sued”), one has to look to the standards promulgated by ERISA and refined by prevailing state and local case law. Admittedly, it is a trustee’s responsibility to understand where his or her state constitution, state statutes, and precedential case law may vary from ERISA. However, understanding fiduciary responsibility under ERISA is a great foundation for understanding the core fiduciary principles for any public (or corporate) pension trustee.

ERISA establishes that:

The assets of every employment benefit plan must be held in a trust managed by one or more trustees, as named fiduciaries9

The assets of every employment benefit plan must be held in a trust managed by one or more trustees, as named fiduciaries9

A fiduciary must discharge his or her duties with respect to the plan solely in the interest of the participants and beneficiaries, specifically in providing benefits and defraying reasonable plan expenses10

A fiduciary must discharge his or her duties with respect to the plan solely in the interest of the participants and beneficiaries, specifically in providing benefits and defraying reasonable plan expenses10

A fiduciary must discharge his or her duties to act with the “care, skill, and diligence” that a prudent person acting in the same capacity would use in similar circumstance11 (this concept is commonly known as the prudent person standard of care)12

A fiduciary must discharge his or her duties to act with the “care, skill, and diligence” that a prudent person acting in the same capacity would use in similar circumstance11 (this concept is commonly known as the prudent person standard of care)12

A fiduciary must prudently diversify the investments of the plan so as to minimize the risk of large loss (this rule is known as the Prudent Investor Rule and is the application of the duty of prudence to investment decision-making).

A fiduciary must prudently diversify the investments of the plan so as to minimize the risk of large loss (this rule is known as the Prudent Investor Rule and is the application of the duty of prudence to investment decision-making).

In 1974 ERISA codified the legal concepts and precedents of the day. However, the concept of fiduciary responsibility goes back centuries, to German, Islamic, or even Roman roots.13 Contemporary trust law has its most immediate roots in English common law. The most significant U.S. legal precedent in the development of the trust law was a case decided in 1830, Harvard College v. Amory.14 This case articulated for the first time a clear, objective behavioral standard for the trustee investment function by imposing the duties of care and loyalty, effectively establishing these two duties at the core of a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility.

Since the enactment of ERISA in 1974, U.S. courts have continued to develop and refine the common trust law concepts and trustee fiduciary responsibility inherent in ERISA. Most scholars turn to the Restatement of the Law Third (Trusts) (hereinafter “Restatement of Trusts” or “Restatement”) to best understand the evolving principles and contours of modern trust law.15 The Restatement of Trusts is meant to reflect the consensus of the American legal community on what is current trust law. As such, the Restatement of Trusts provides not only the clearest summary or outline of the specific duties that encompass a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility but also establishes how a trustee can be in violation of these duties.

Duties of a Fiduciary

Trustees have broad discretionary power but with clear fiduciary safeguards. The best way to understand a trustee’s fiduciary responsibilities is to understand this responsibility not as an amorphous legal concept, but rather as a basket of specific legal duties—the specific duties of trusteeship. To help better understand the genesis and meaning of the duties of trusteeship, this chapter groups these duties into seven primary categories, with corresponding subordinate responsibilities. These primary and subordinate obligations, in total, represent a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility and are listed in Chart 13.1.

Chart 13.1 Framework for Trustee Fiduciary Duty

The remainder of this chapter will discuss each of these specific duties, some in more detail than others. This review is not meant to be an exhaustive legal treatment of these seven concepts. And a trustee should speak to his or her plan’s general counsel or other appropriate legal advisor to appreciate the full legal complexity of these duties in his or her jurisdiction. Rather, what follows is an overview meant to highlight basic legal concepts and, in doing so, begin to inform a trustee of the depth of his or her responsibilities.

Duty of Prudence

A public pension trustee has the duty to administer a trust “as a prudent person would, in light of the purposes, terms, and other circumstances of the trust.”16 Prudence is paramount. So central is the concept of prudence to the role of a trustee that the concept is itself defined by three specific trustee duties. The Restatement highlights that prudence requires that a trustee “exercise reasonable care, skill, and caution” (emphasis added).17 As such, to understand the duty of prudence, one must understand the meaning of the care, skill, and caution that a trustee must exercise in the performance of his or her role.

The duty of care required by a trustee means making reasonable effort and diligence in administering and monitoring the trust on behalf its beneficiaries.18 Such effort and diligence require a trustee to obtain and review relevant information and conduct appropriate investigations concerning a particular action under consideration. I think of the care a trustee is required to employ the “do your homework rule”—collect and review the information necessary to make an informed judgment on the matters at hand.

The duty of prudence also calls for a trustee to exercise the duty of skill of an individual of ordinary intelligence.19 At a minimum, “a person who serves as trustee should be reasonably able to understand the basic duties of prudent trusteeship.”20 Many aspects of public pension trusteeship require greater (or different) skills and knowledge than what a typical trustee may have—this does not normally prevent a trustee from dutifully serving in the role. “This just emphasizes the importance of obtaining competent guidance and assistance sufficient to satisfy the standards required by the combination of care and skill in given situation.”21 Many trustee functions will require a trustee who lacks the skill or expertise (typically legal or financial) needed to make an informed decision to seek the advice of those who have these particular skills. A trustee “may either possess or hire the degree and types of skill needed for a specific transaction” or required by the broader needs of public pension trust administration.22

Moreover, if a trustee actually does possess a degree of skill beyond that of a person of ordinary intelligence (again, typically financial or legal expertise), then the prudence standard requires that the trustee use that skill when appropriate.23 In fact, a trustee is ordinarily liable for the failure to do so.24 I like to consider the prudence requirement of skill satisfied by what I call the “if you have the skill, use it; if not, hire it” rule. This last point is particularly poignant for trustees who are brought onto a pension board specifically for their particular skill or expertise (i.e., legal, financial, etc.). Chapter 15 will raise the issue of whether this additional burden and potential liability acts as a disincentive for skill professionals to serve as trustees.

Finally, the duty of caution requires that a trustee exercise the caution of a prudent person managing similar assets for similar purposes. Trustees are required to use the level of caution that would be considered reasonably appropriate, given the circumstances. I call this obligation the “proceed with caution rule in decision-making,” which is simple enough on its face. The duty of prudence is a test of a trustee’s conduct, not the result of that conduct. So the outcome of a trustee’s decision is not what counts. A trustee’s prudence is evaluated on the basis of the circumstances at the time of behavior, “not with the benefit of hindsight or by taking account of developments that occurred after the time of the action or decision.”25

More often than not, satisfying a trustee’s duty of prudence depends on whether the trustee can demonstrate that he or she engaged in the appropriate due diligence before acting. For example, in one New York case, trustees were found to have acted imprudently in a real estate purchase because the trustees failed to obtain either a valuation or appraisal of the real estate in question and failed to participate in any of the negotiations of the purchase price.26 In another dispute involving a union pension plan, the court found that the trustees violated their duty of prudence in their attempts to commit 23% of the pension plan’s total assets in a single loan.27 However, another court found that imprudence cannot be established by evidence only of a loss in investment value of an asset.28

Concerning a trustee’s reliance on and delegation to experts, a court found that a trustee acted imprudently when following the advice of an actuary without determining if the actuary was competent and if the recommendation itself was based on accurate and current information.29 In addition, one court clarified this by establishing that to prudently select an investment manager, trustees must consider the manager’s qualifications, reasonableness of fees, nature of the contractual relationship, and extent to which the manager would be periodically reviewed.30

Duty of Loyalty

A trustee’s duty of loyalty, like the duty of prudence, is a core fiduciary concept. Trustee loyalty is a must. And, like the duty of prudence, the duty of loyalty is composed of three distinct obligations: a duty of undivided loyalty, a prohibition against self-dealing, and a duty of fair dealing.31 The duty of undivided loyalty is at the heart of the fundamental relationship between a trustee and a beneficiary concerning all matters within the scope of the trust relationship. A public pension trustee must act “solely in the interest of the beneficiaries” (emphasis added).32 A trustee works for, and in the interest of, the beneficiaries he or she serves. A trustee is required to put the interests of his or her beneficiaries ahead of his or her own self-interest and the interest of nonbeneficiaries in administering a trust. This duty, broad in its applicability, too, is simple on its face. I like to refer to this duty as the “it’s all about the beneficiaries” rule.

The prohibition against self-dealing strictly prohibits a public pension trustee from entering into transactions involving trust property, or affecting the investment or management of trust property, if the transaction is for the trustee’s personal benefit (self-dealing).33 A public pension trustee must avoid any conflicts of fiduciary responsibility and personal interest, and if there is any doubt, trustees are required to put their personal interest aside. Even if a transaction does not involve trust property, a trustee is prohibited from personally engaging in it if that transaction could place the trustee in a position where the trustee’s personal interests and fiduciary responsibility may conflict.34 A public pension trustee must also avoid transactions that may cause future conflict with that trustee’s fiduciary responsibility and his or her personal interest—again, the former trumps the latter. I like to call this the “trusteeship is not for personal gain” rule.

The duty of fair dealing requires that a public pension trustee, when dealing with a beneficiary, do so “fairly” and “communicate to the beneficiary all material facts the trustee knows or should know in connection with the matter.”35 The duty of fair dealing really touches upon the position of influence a trustee has over the beneficiary. It applies to all potential trustee/beneficiary transactions, including those that may fall outside of the duty of undivided loyalty and the prohibition against self-dealing. For example, the duty of fair dealing even covers personal transactions with beneficiaries that do not “involve trust property and are not within the scope of the trust relationship.”36 As long as a trustee is in a position to exert influence over a beneficiary, the duty of fair dealing requires fairness and full disclosure in transactions with that beneficiary. I like to call this the “don’t hustle the beneficiaries” rule.

There is an exception to the duty of loyalty rule. A trustee can engage in transactions prohibited by the rule if he or she is essentially required to do so. A trustee may be required to do so if (1) authorized by the proper court, (2) authorized by the explicit or implicit terms of the trust, or (3) authorized by the all of the beneficiaries.37 In the end, a public pension trustee is solely responsible for, and ultimately accountable to, the plan beneficiaries—no one else, and definitely not the trustee himself or herself. The trustee role should not be treated as a platform for personal benefit. Nor should a trustee leverage his or her preferential position vis-à-vis a beneficiary for trustee gain. The role of a trustee is a role of true public servant. It is a role of trust. Without a doubt, trustee misbehavior that finds its way into the headlines typically violates this very basic understanding.

For example, an investment advisory firm violated its duty of loyalty by investing a significant portion of plan assets in companies in which advisory firm members themselves had substantial equity interests.38 In another dispute, a court rejected the petition of a trustee to sell trust property to himself, finding that the law disfavors a trustee selling trust assets to himself and that the trustee failed to show any specific benefit to the trustees through the sale.39 These trustees were found personally liable for the breach of their fiduciary responsibility as a result of making improper loans between themselves and the plan.40 Trustee liability will be discussed later in this chapter.

The duty of prudence and the duty of loyalty form the foundation of a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility. In fact, all the subsequent duties discussed here can be derived from these two more fundamental obligations.

Duty of Impartiality

The duty of impartiality establishes that a “trustee has a duty to administer the trust in a manner that is impartial with respect to the various beneficiaries of the trust.”41 The duty of impartiality is an extension of the duty of loyalty, and is applicable to all the duties of a public pension trustee. It is meant to be a guide through the often and unavoidable conflicting duties to various beneficiaries with their potentially competing economic interests. The duty of impartiality does not require an equal balancing of diverse interest, but rather a balancing of those interests in a manner that shows due regard for, and is consistent with, the beneficial interest and the terms and purposes of the trust.42

It is a trustee’s duty, reasonably and without personal bias, to seek to ascertain and to give effect to the rights and priorities of the various beneficiaries or purposes of the trust. The duty of impartiality not only applies to investing, protecting, and distributing trust assets but also to consulting and communicating with beneficiaries.43 The core of this duty is to prohibit personal favoritism or animosity toward individual beneficiaries in making decisions among competing beneficiary interests. A trustee must be fair and impartial to all beneficiaries with their varied interests. As such, I like to call the duty of impartiality the “no beneficiary favoritism” rule.

One corollary of the duty of impartiality is the duty of income productivity. The duty of income productivity clearly means that a public pension trustee has “a general duty to the income beneficiary not to retain or purchase unproductive or underproductive (low income) property” to the extent that it hurts the beneficiary “through an inadequate income yield from the trust estate as a whole.”44 This duty of income productivity applies to the whole trust portfolio, not individual assets.45 The duty of income productivity also requires that a trustee, when managing the principal and income of a trust, must be impartial between current and future beneficiaries of the trust. A trustee is required to invest and administer the trust so that “the trust estate will produce income that is reasonably appropriate to the purpose of the trust and to the diverse present and future interest of the beneficiaries.”46 I like to call this the “invest for beneficiaries today and tomorrow” rule.

In one case, a court found that plan trustees breached their duty of impartiality by adopting a pension plan amendment that was drafted by a union representative with no independent review that conferred benefit primarily to that union.47 In another case, a court found that trustees did not violate their duty of impartiality when they approved pension increases that were much greater for employees still working than for retirees already receiving their pensions.48 This court reasoned that there could be a good business and actuarially sound reason for the proposed increases.49 In the end, a public pension trustee must work not only to meet the pension obligations of current vested beneficiaries but must also be making decisions that consider pension obligations of unvested beneficiaries and future plan participants.

Duty with Respect to Delegation

An individual who has accepted the role of trustee is a person who has accepted a special role, the responsibilities of which are purposefully hard to abdicate or outsource. In the past, a trustee’s ability to delegate was more restricted than it is today—restricted to mere ministerial acts and only allowed when a trustee had no other reasonable alternative but to delegate.50 Most significantly, trustee delegation of investment authority was explicitly prohibited.51 Modern portfolio theory and the increasing complexity of potential pension investments have played their part in easing a trustee’s ability to delegate. The bottom line is that “trustees need help too,” an appropriate shorthand maxim for this duty.

Today, a trustee “has a duty to perform the responsibilities of the trusteeship personally, except as a prudent person of comparable skill might delegate those responsibilities to others.”52 The decision to delegate is a matter of fiduciary judgment and discretion.53 In deciding whether, to whom, and in what manner to delegate, the duty of prudent delegation requires that a trustee “exercise fiduciary discretion and to act as a prudent person of comparable skill would act in a similar situation.”54 I like to call this the “delegation requires prudence” rule. Finally, in certain situations, prudence may actually require a trustee to delegate, specifically when the trustee does not personally have the skill or expertise to prudently perform his or her duties.55 The duty of skill requirement supports this obligation as well.

An agent is a person “to whom a trustee delegates the performance of specified fiduciary duties or functions and grants authority to exercise corresponding powers of the trusteeship.”56 The most common form of public pension trustee delegation is typically to internal pension investment or administrative staff. The second most common public pension trustee delegation is to external investment managers. It is important to note that a trustee receiving and acting upon a consultant’s advice is not a delegation. “A trustee, in acting personally and without the effect of delegation, may consult with and receive advice from others, such as accountants, legal counsel, and financial advisors.”57 Moreover, the limitations on delegation do not apply to delegation to, or the allocation of, functions between or among co-trustees.

Modern case law has given a trustee greater flexibility to delegate, but that flexibility now imposes a post-delegation responsibility: the duty to monitor and supervise the trustee’s agent.58 A trustee must exercise the same fiduciary discretion in the monitoring and supervising of the trustee’s agent as was required and used in the decision to delegate in the first place. I like to call this the “watch your agents” rule.

Although current law is more permissive of delegation than before, a trustee’s discretion to delegate may be abused by either improperly delegating or imprudently failing to delegate. A trustee who prudently delegates—acts with reasonable care, skill, and caution—is not personally liable to the trust or the beneficiaries for the decisions or actions of the agent to whom the function was delegated. A failure to act prudently in selecting the agent and defining the scope of the delegation would expose a trustee to personal liability. A trustee who fails to prudently supervise or monitor an agent similarly would violate his or her fiduciary responsibility. A failure to delegate to an agent when prudence requires a trustee to do so would expose a trustee to personal liability as well.

A trustee was found to have violated his duty to properly delegate by delegating authority for the management of a real estate fund to a trust officer with neither experience nor expertise in managing real estate.59 Similarly, a court found that the trustees had abused their discretion in delegating the responsibility to monitor an investment fund to internal staff when that staff was without sufficient size or expertise to effectively monitor.60 The court emphasized that a fact finder could conclude that turning to outside assistance with the necessary expertise to monitor the investment would have been necessary to satisfy the duty of reasonable prudence.61 Another court held that the fact all administrative functions had been delegated to the plan administrator still did not absolve trustees of their duty to review and ensure that the administrator was acting in the best interests of the participants.62 And in another dispute, a court held that the fiduciary had the duty to monitor the investment manager’s performance with reasonable diligence and to withdraw the investment if it became clear, or should have been clear, that the investment was no longer proper for the plan.63

The next chapter will discuss the importance and implication of the rules governing public pension trustee delegation in more detail, as increasingly complex investment approaches and products, combined with the sheer size of the average public pension plan in the United States, require greater focus on, and understanding of, the proper scope of public pension trustee delegation. Chapter 14 will also discuss delegation in the context of the investment infrastructure of the modern public pension, focusing on both the increasing need to delegate and the implications of the burden of monitoring and supervising within the context of the investment function.

Duty with Respect to Co-Trustees

Except in a sole trustee governance model, a public pension trustee typically serves on a board, with other trustees, as a co-trustee. A trustee’s duty with respect to co-trustees remains an often-overlooked element of fiduciary responsibility. I like to refer to the overall duty with respect to co-trustees as the “trusteeship is a team sport” rule.

If a trust has more than one trustee, then “each trustee has a duty and right to participate in the administration of the trust.”64 The duty and right to participate is a coin with two sides. First, the “duty” requires active, prudent participation by each trustee.65 Every board of trustees has one or two of its members who are notorious for not showing up to meetings or fulfilling other basic obligations. Don’t be that trustee. Although the duty to participate does not require equal levels of effort or activity by co-trustees,66 the duty to participate does hold a trustee accountable to the beneficiaries he or she serves for a basic level of commitment to the role. The other side of the coin, the “right,” prevents a trustee from being excluded from the decision-making of trust administration. Individual trustees should not and cannot be excluded from discussions or decision-making due to personality or temperament. I like to call this the “participate and not exclude” rule.

The duty to participate also implies “a duty of reasonable cooperation among the trustees.”67 The duty of reasonable cooperation is necessary because trustees need to maintain effective working relationships, at a minimum, for proper trust administration. In trusts that have three or more trustees, absent contrary provisions in the terms of the trust, fiduciary authority is determined by majority vote.68 In getting to this majority, the duty of cooperation requires basic levels of civility and decorum among co-trustees—sometimes easier said than done in practice. I like to call this the “can we all just get along” rule.

A trustee’s duty with respect to co-trustees also requires that each trustee “use reasonable care to prevent a co-trustee from committing a breach of trust and, if a breach of trust occurs, to obtain redress.”69 As a result, the duty to prevent co-trustee breach means that a trustee can breach his or her own fiduciary obligations by knowingly allowing a co-trustee to commit a breach of that trustee’s fiduciary responsibility.70 And if a breach does occur, a trustee must take reasonable steps to compel that co-trustee to remedy the breach. Linking one trustee’s fiduciary duty to the proper execution of another trustee’s fiduciary responsibility should clearly signal to all co-trustees that they are in the role of administering the trust together and should act accordingly. I like to call this the “I am my co-trustee’s keeper” rule.

One court found that co-trustees owed each other and their beneficiaries the duty and obligation to conduct themselves so as to foster a spirit of mutual trust, confidence, and cooperation to the extent possible.71 Another court held that a trustee’s failure to act and failure to monitor the actions of his co-trustee’s mismanagement did not excuse the first trustee from liability for the plan’s losses.72 The court reasoned that the law does not make a trustee an ensurer against co-trustee misconduct but does require a trustee to use reasonable care to prevent such a breach by his peer.73

Duty to Furnish Information to Beneficiaries

Fiduciary responsibility requires that a public pension trustee provide certain types of information to beneficiaries. Trustees must “promptly inform fairly representative beneficiaries” of basic trust information, their status as beneficiaries and any significant changes to their beneficiary status, or any other information material to the protection of the beneficiaries’ interests.74 Fairly representative beneficiaries are meant to be a cross-section of beneficiaries “reflecting the diversity of the beneficial interests and beneficiary concerns of the trust.”75 In addition, a trustee is required to promptly respond to beneficiary requests for information about the trust and to permit beneficiaries a reasonable opportunity to inspect trust documents, records, and holdings.76 I like to call this the “keep the beneficiaries in the know” rule.

A public pension trustee’s duty to keep records and provide reports stems from the duty to furnish information to beneficiaries. A trustee is required to “maintain clear, complete, and accurate books and records regarding trust property and the administration of the trust” and periodically provide such reports or accountings to beneficiaries.77 This is the reporting requirement of a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility that may be satisfactorily discharged by simple, orderly forms of bookkeeping and record maintenance, as well as disclosing information in a manner that will enable beneficiaries to determine whether the trust is being property administered.78 Such information is typically in the form of periodic reports that reveal trust assets and liabilities, receipts and disbursements, and other transactions involving trust property.79 This information must also disclose the amounts and bases of compensation paid to the trustees and any agents during the accounting period covered by the report.80 I like to call this “report, report, and then report again” rule.

For example, upon hearing of possible changes to his health care coverage, an HIV-positive plaintiff requested and received misleading and incomplete information resulting in actions terminating his coverage on the eve of needed surgery. A court in this case found a breach of fiduciary duty, highlighting that once a participant or beneficiary makes an inquiry, a fiduciary has a duty to make correct and complete material information available to that participant or beneficiary.81 In another case, an employee heard a rumor that the plan was going to offer a new lump-sum distribution. The court held that a fiduciary violated his duty to furnish information to a beneficiary by not disclosing possible changes that were under serious consideration by the plan.82

Duty to Segregate and Identify Trust Property

A public pension trustee has the duty to identify trust property, separate it from the trustee’s own property, and separate it from other property not subject to the trust.83 The duty to segregate and not to commingle trust property with a trustee’s own property is really a prohibition required by the duty of loyalty, to avoid a potential conflict of interest. The duty to separate trust property from “property not of the trust” is really a rule for those who are fiduciaries to multiple trusts. It is ordinarily a prohibition against mingling property held in one trust with property held in another trust, regardless of whether the trusts are created by the same a or different settlor.84 Moreover, there is an additional protection involved in the identification requirement: that of fraud detection. A “particular concern exists when commingling (or lack of identification) might make trustee misconduct or abuse difficult to detect.”85 I like to call this the “keep trust property separate” rule.

One court found that a trustee who invested employee benefit plan assets without separating the investment from his own breached his common-law duty to segregate the plan assets.86 Another court affirmed the dismissal of trustees for misusing the assets of one trust for the fees and operating expenses of other trusts.87 The court noted that the unauthorized and undocumented cross-usage of funds contravened the duty to segregate.88

Trustee Liability

When a public pension trustee violates his or her fiduciary responsibility, that trustee breaches the trust of the beneficiaries he or she serves. An alleged breach of trust, and resulting fiduciary litigation, has traditionally charged a trustee with one (or both) of the following forms of misconduct: (1) that a trustee undertook to perform an act that the trustee was not empowered, either by law or by terms of the trust, to perform or (2) that even if the act in question was one the trustee had the power to perform, the trustee exercised that power in a manner inconsistent with the applicable standards of fiduciary conduct.89 Therefore, for a trustee to avoid legal liability, he or she must act within the scope of “the terms and purposes of the trust” and comply with the fiduciary duties outlined earlier.90

If a trustee were to breach his or her fiduciary duty, that trustee would be personally liable for any losses resulting from the breach and required to restore any profits the trustee made through the use of plan assets.91 The trustee would also potentially be subject to other equitable or remedial relief that a court may deem appropriate, including removal.92 Nothing, however, prevents a public pension plan from purchasing insurance for its fiduciaries or for itself to cover liabilities or losses due to trustee breach of fiduciary responsibility.93 Moreover, nothing prevents a trustee from purchasing insurance to cover his or her own potential liability as well.94

Bottom line to trustees: Know and understand your fiduciary responsibilities and comply with the duties and obligations. If the trustee misconduct is extreme enough, the consequences could be financially crushing and potentially result in jail time, a very costly and severe outcome that can be avoided by simply understanding and following the rules.

Chapter Notes

This chapter used the Restatement of the Law Third (Trusts) as the principal source for the description and discussion of trustee duties and responsibilities. Existing case-law precedents were added to this discussion to give trustees and pension fiduciaries a better feel for how their decision-making and behavior would be seen through the legal lens of fiduciary responsibility.

Upon reviewing the contents of this chapter, a reader should remember the following:

State and local governments are exempt from the requirement of ERISA, though they are still subject to federal tax laws.

State and local governments are exempt from the requirement of ERISA, though they are still subject to federal tax laws.

The current legal framework governing public pension fiduciaries is a combination of state constitutional law, state statutes, and evolving case law. In aggregate, this combination is substantially similar to ERISA in terms of the protection of plan participant benefits, vesting requirement, financial reporting, and standards of fiduciary responsibility.

The current legal framework governing public pension fiduciaries is a combination of state constitutional law, state statutes, and evolving case law. In aggregate, this combination is substantially similar to ERISA in terms of the protection of plan participant benefits, vesting requirement, financial reporting, and standards of fiduciary responsibility.

The seven core duties that collectively represent a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility are (1) prudence, (2) loyalty, (3) impartiality, (4) respect for delegation, (5) respect for co-trustees, (6) required information disclosure to beneficiaries, and (7) the segregation and identification of trust property.

The seven core duties that collectively represent a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility are (1) prudence, (2) loyalty, (3) impartiality, (4) respect for delegation, (5) respect for co-trustees, (6) required information disclosure to beneficiaries, and (7) the segregation and identification of trust property.

Chart 13.1 comprehensively illustrates these responsibilities and their underlying obligations.

Chart 13.1 comprehensively illustrates these responsibilities and their underlying obligations.

The duty of prudence and the duty of loyalty form the foundation of a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility. In fact, all the subsequent duties discussed in this chapter can be derived from these two more fundamental obligations.

The duty of prudence and the duty of loyalty form the foundation of a trustee’s fiduciary responsibility. In fact, all the subsequent duties discussed in this chapter can be derived from these two more fundamental obligations.

In that this legal framework is based on case law, it evolves as legal concepts evolve.

In that this legal framework is based on case law, it evolves as legal concepts evolve.

A trustee is required to understand how this general fiduciary framework and its responsibilities, as explained through The Restatement of the Law Third (Trusts), may be different in his or her jurisdiction.

A trustee is required to understand how this general fiduciary framework and its responsibilities, as explained through The Restatement of the Law Third (Trusts), may be different in his or her jurisdiction.