Why is it so difficult to have a political discussion with those who disagree with us? Why do discussions about controversial issues so often devolve into angry shouting matches? As I mentioned earlier, all societal problems— such as racism, sexism, injustice, war, and environmental destruction—come from how people think. And all progress comes from transforming how people think. But how are we supposed to transform how people think when we cannot have a productive conversation with those who disagree with us? How are we supposed to change attitudes about a controversial issue when so many people’s minds seem resistant to change? How are we supposed to end war when so many Americans perceive peace activists as unpatriotic hippies who are a threat to national security?

To understand the answers to these questions, we must first understand how the human mind works. Have you ever wondered why you cannot discuss politics and religion in a civilized way with most people? Have you ever wondered why people can become so aggressive and hostile when discussing controversial issues? I wondered these same things at West Point when one of my friends told me, “Never discuss politics, religion, or any controversial issue with people. It’s a waste of time, because people never listen and get very angry when their viewpoints are questioned.” Ever since he told me that, I was determined to find a way to dialogue about important and controversial issues. I thought, “Since the most serious problems in our world are also controversial, how will anything ever change for the better if we cannot discuss controversial issues in a productive and civilized way?”

My determination to understand the art of dialogue led me to a deeper understanding of the human condition. Just as the human body requires physical necessities such as food and water to survive, the human mind requires psychological necessities such as a worldview and sense of identity to remain sane. In his book The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, psychologist Erich Fromm says that when others assault our worldview and sense of identity, we will often react with aggression as if they were threatening our physical body. This is because new ideas that attack our worldview and sense of identity can endanger our “psychic equilibrium,” which is another way of saying our “mental stability.” Erich Fromm explains:

Man, like the animal, defends himself against threat to his vital interests. But the range of man’s vital interests is much wider than that of the animal. Man must survive not only physically but also psychically. He needs to maintain a certain psychic equilibrium lest he lose the capacity to function; for man everything necessary for the maintenance of his psychic equilibrium is of the same vital interest as that which serves his physical equilibrium. First of all, man has a vital interest in retaining his frame of orientation. His capacity to act depends on it, and in the last analysis, his sense of identity. If others threaten him with ideas that question his own frame of orientation, he will react to these ideas as to a vital threat. He may rationalize this reaction in many ways. He will say that the new ideas are inherently “immoral,” “uncivilized,” “crazy,” or whatever else he can think of to express his repugnance, but this antagonism is in fact aroused because “he” feels threatened.1

A frame of orientation, also known as a worldview, is just as important to our mind as oxygen is to our body. We need a worldview, a way of orienting ourselves to our surroundings, in order to remain sane. When we threaten people’s worldview with new ideas, they will often respond with the same aggression as if we were threatening their physical body. When Galileo proposed a new view of the universe, where the planets revolve around the sun, the leaders of the Roman Catholic Church reacted with aggression as if Galileo had held a knife to their throats. Galileo had threatened their worldview, and throughout history a common punishment for challenging the predominant worldview was ridicule, imprisonment, or even execution.

The human condition requires us to have a worldview, but the human condition does not require us to always be afraid of new ideas. Throughout history all progress has resulted from new ideas that change how people think. Democracy, the right to vote, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and women’s and civil rights became widespread, for example, because new ideas changed how people thought and perceived their humanity.

When someone promotes a new idea, such as ending racial segregation in America, a minority of people will react with fear and aggression no matter what. But the majority of people are capable of accepting a new idea without fear if we use the right approach. We can use a simple yet effective technique to make a new and controversial idea sound more persuasive and less threatening. To do this, connect a new idea to a familiar idea. This can be accomplished by framing a new idea within their current worldview, rather than using a new idea to directly assault their worldview. In his book Strategy, military historian Liddell Hart explains:

In all such cases, the direct assault of new ideas provokes a stubborn resistance, thus intensifying the difficulty of producing a change of outlook . . . Opposition to the truth is inevitable, especially if it takes the form of a new idea, but the degree of resistance can be diminished—by giving thought not only to the aim but to the method of approach. Avoid a frontal attack on a long established position; instead, seek to turn it by flank movement, so that a more penetrable side is exposed to the thrust of truth. But, in any such indirect approach, take care not to diverge from the truth—for nothing is more fatal to its real advancement than to lapse into untruth.

The meaning of these reflections may be made clearer by illustration from one’s own experience. Looking back on the stages by which various fresh ideas gained acceptance, it can be seen that the process was eased when they could be presented, not as something radically new, but as the revival in modern terms of a time-honored principle or practice that had been forgotten. This required not deception, but care to trace the connection . . . A notable example was the way that the opposition to mechanization was diminished by showing that the mobile armored vehicle—the fast-moving tank—was fundamentally the heir of the armored horseman, and thus the natural means of reviving the decisive role which cavalry had played in past ages.”2

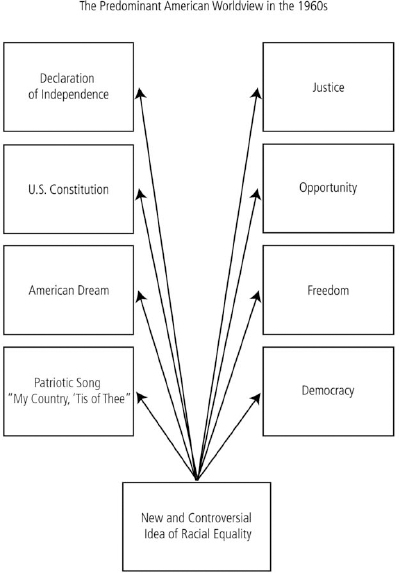

For example, ending racial segregation in America was a new and controversial idea that threatened the worldview of many people, challenging everything they had ever been taught. But Martin Luther King Jr. used a very intelligent approach. He connected the new idea of racial equality to the Declaration of Independence, the American dream, and our most cherished American ideals such as justice, opportunity, freedom, and democracy. In his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, King did not directly assault the worldview of white Americans. Instead, he brilliantly delivered a speech that framed the new idea of racial equality within their current worldview. In the following excerpt from the “I Have a Dream” speech, I have italicized the instances where King connected the new idea of racial equality to concepts familiar to most Americans.

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights of Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

[In the following paragraph King ties the new idea of racial equality to cherished American ideals such as justice, opportunity, freedom, and democracy.] But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice . . . Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy . . .

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. [Here King is tying his dream of racial equality to the American dream.] I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood . . .

This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning:

My country, ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing.

Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride,

From every mountainside, let freedom ring!3

Figure 10.1 shows how Martin Luther King Jr. strategically connected the new and controversial idea of racial equality to the powerful ideals contained within the predominant American worldview. As I explained in chapter 5, it is impossible to convince every single person. But for progress to happen, we don’t have to convince every single person; we just have to convince enough people. King’s strategic approach made the new idea of racial equality much more persuasive to the majority of Americans.

The “I Have a Dream” speech is one of the most moving, inspiring, and patriotic speeches I have ever read. The word “patriotism” makes many peace activists cringe, because that word has been misused and abused by American politicians and the media, especially after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. For example, peace activists were called unpatriotic for questioning whether our country should go to war. As a result, many people today associate patriotism with blind obedience and aggressive nationalism, but that is not what patriotism truly means.

The simplest and least controversial definition of patriotism is “love of country.” But what does it mean to truly love our country? As I explain in Will War Ever End?, we can better understand love of country by realizing what it means to love a child. Parents who love their children will try to correct a child caught stealing, abusing people, or being dishonest. For parents who do not truly love their children, apathy will cause them not to care, enabling their children to get away with anything. In this same way, if we love our country we will do our best to improve it. We will try to make America a better place for everyone, as courageous citizens have always done.

Since our country’s founding, brave patriots have worked to give us the many freedoms we enjoy today. Two hundred years ago in America, anyone who was not a white, male landowner suffered oppression. During this era, the majority of people lacked the right to vote, and many Americans lived as slaves. Our country is much more humane today than it was then. This happened because courageous citizens such as Martin Luther King Jr., Mark Twain, Helen Keller, Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Woody Guthrie, Smedley Butler, Henry David Thoreau, and many others struggled to make our country a better place for all people.

Figure 10.1 How Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech connected the new and controversial idea of racial equality to the powerful ideals contained within the predominant American worldview

Because of the patriotic Americans who loved and were therefore willing to question, constructively criticize, and improve their country, America has made a lot of progress. When my father was drafted into the army in 1949, the military was segregated because the government upheld an official policy that viewed African Americans as inferior and subhuman. Fifty years before then, the government would not allow women to vote, and only fifty years prior to that, the government supported and protected slavery.

I have met peace activists who refuse to use phrases such as “patriotism” and “love of country” to describe their work for peace, because they feel that the advocates of war have monopolized and corrupted those terms. But if we refuse to use a word because someone else uses it in a way we don’t like, then eventually we will run out of words to use.4 Phrases such as “patriotism” and “love of country” are so powerful that we can no longer afford to let the advocates of war monopolize and corrupt them.

In ancient battles an army gained an advantage when it occupied “high ground” such as a hilltop. On the battlefield of ideas, patriotism and love of country are high ground that give us an enormous strategic and persuasive advantage, and we must take back the high ground. When a social movement’s message can authentically stand atop the high ground of patriotism and love of country, the movement will appeal more broadly to the masses. Mark Twain also said we must take back the meaning of words such as patriotism. In 1905 he explained, “Remember this, take it to heart, live by it, die for it if necessary: that our patriotism is medieval, outworn, obsolete; that the modern patriotism, the true patriotism [emphasis added], the only rational patriotism, is loyalty to the Nation all the time, loyalty to the Government when it deserves it.”5

In 1967 Martin Luther King Jr. said, “We believe the highest patriotism [emphasis added] demands the ending of the [Vietnam] war and the opening of a bloodless war to final victory over racism and poverty.”6 In 1882 women’s rights activist Olympia Brown said, “Now was the time for every true patriot [emphasis added] to demand that no new State should be admitted except on the basis of suffrage to women as well as negroes.”7

During the American Revolution, “patriots” such as Founding Father Thomas Paine rebelled against tyranny and challenged the status quo. Those are the same kind of patriots we need today. General Dwight Eisenhower believed all worthwhile progress requires dissent and that opposing injustice is the highest form of patriotism. He said, “Here in America we are descended in blood and in spirit from revolutionaries and rebels—men and women who dared to dissent from accepted doctrine. As their heirs, may we never confuse honest dissent with disloyal subversion.”8

In the army I learned that being loyal to your leaders requires you to question them. If your commander’s plan is flawed, the highest form of loyalty is disagreeing with the plan whether your superior officer wants to hear it or not. On the other hand, letting your commander march toward disaster without properly expressing your disagreement is an act of disloyalty.

Telling the truth can put us at personal risk, because people may not be kind to those who bear bad news, hence the saying “Don’t shoot the messenger.” But to truly be loyal we must be willing to take that risk. As I mentioned in chapter 5, the Code of the Samurai tells us, “Once you have become someone’s confidant, it shows a certain degree of dependability to pursue the truth and speak your mind freely even if the other person doesn’t like what you say. If, however, you are fainthearted and fear to speak the truth, lest you cause offense or upset, and thus say whatever is convenient instead of what is right, thereby inducing other people to say things they shouldn’t, or causing them to blunder to their own disadvantage, then you are useless as an advisor.”9

As American citizens, we have a sacred duty to love and be loyal to our country. This means correcting the politicians who run our government when they stray from the path of justice. This means taking the harder path of love and loyalty over the convenient path of apathy and disloyalty. When King spoke against the Vietnam War in his speech “Beyond Vietnam,” he said, “I speak as one who loves America.”10 If we truly love our country, we will work hard to help it achieve its full potential by correcting its mistakes, and we will do what is necessary to serve and sacrifice for our nation, even if it means taking a stance that makes us unpopular. The same can be said of parents who truly love their children.

Just as parents who do not let their children eat a lot of junk food may be less popular than parents who let their children get away with anything, doing what is right for our country can also make us less popular than those who enable harmful behavior. In the Bible, the prophets who flattered the king were much more popular within the royal court than the prophets who challenged the king’s injustice. The flatterers were later called “false prophets,” while those who challenged the king’s injustice were recognized by later generations as the true prophets. During their lives, however, the false prophets were often rewarded by the king, while the true prophets were usually punished.

When Martin Luther King Jr. spoke against the Vietnam War, many of his friends and allies turned against him. The NAACP and many black churches disowned him, and his own organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, issued a public statement criticizing his stance on the war. But during a 1967 television interview on The Mike Douglas Show, King said:

I think the things that I’m saying and the things that I’m trying to do and all of the people in the peace movement are trying to do are really geared toward bringing the boys [U.S. soldiers] back home. In other words, we are trying to prove to be their best friends by doing something to bring about the climate that will bring an end to this war . . . When I first spoke out against the war, only twentyone percent of the American people were against it. Both the Gallup and the Harris polls reveal now that the majority of Americans are against the war in Vietnam . . .

A man of conscience can never be a consensus leader. He doesn’t take a stand in order to search for consensus. He is ultimately a molder of consensus. And I’ve always said that the ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and moments of convenience, but where he stands in moments of challenge and moments of controversy. And I would take this position [against the Vietnam War] even if I didn’t have the majority of people agreeing with me now.11

The U.S. Army has a saying, “We need leadership, not likership.” What does this mean? The army taught me that “leadership” means doing what is right, while “likership” means doing what is popular in order to be liked— with no concern for whether your actions are right or wrong. In a democracy, “what is right” usually becomes a majority position only after overcoming the long and difficult path of being a minority position. To offer an example, most Americans today support women’s right to vote and oppose slavery and segregation. But these viewpoints used to be extremely unpopular, and the advocates of racial and gender equality were ridiculed and attacked for challenging popular support for slavery, segregation, and the oppression of women.

Just as the advocates of racial and gender equality transformed attitudes in America, Martin Luther King Jr. realized that our democracy cannot function correctly unless conscientious citizens become “molders of consensus” who also transform attitudes. But to transform attitudes, especially toward controversial issues, we must have a persuasive message that resonates with many people who do not already agree with us. In other words, we must do more than preach to the choir.

When we connect a new and controversial idea to powerful ideals such as patriotism (love of country), justice, opportunity, freedom, and democracy, our new idea becomes much more persuasive. Martin Luther King Jr. was not the only pioneer who connected new ideas to powerful ideals within people’s existing worldviews. Although new ideas such as women’s rights and ending slavery sounded controversial and radical in the nineteenth century, the ingenious women’s rights activists of that era framed these new ideas in a way that did not directly assault the worldview of most Americans.

In 1866, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Theodore Tilton, and Frederick Douglass made a statement on behalf of the American Equal Rights Association. They connected the new idea of racial and gender equality to the powerful ideals of the American Revolution: “Woman and the colored man are loyal, patriotic, property-holding, tax-paying, liberty-loving citizens; and we cannot believe that sex or complexion should be any ground for civil or political degradation . . . And is not our protest pre-eminently as just against the tyranny of ‘taxation without representation’ as was that thundered from Bunker Hill, when our revolutionary fathers fired the shot that shook the world?”12

During the first convention for women’s rights in 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote a declaration affirming the rights of women. Known as the “Declaration of Rights and Sentiments,” it became the founding document of the women’s rights movement. In an act of strategic brilliance, she connected the new and controversial idea of women’s rights to the greatly admired founding document of America: the Declaration of Independence. In the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, she even borrowed many popular phrases from the Declaration of Independence. Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women [emphasis added] are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”13

Frederick Douglass also connected the new and controversial idea of women’s rights to the Declaration of Independence. In 1853 he said, “Whereas, according to the Declaration of our National Independence, Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, we earnestly request the Legislature of New York to propose to the people of the State such amendments of the Constitution of the State as will secure to Females an equal right to the Elective Franchise with Males.”14

By connecting the new and controversial idea of women’s rights to our highest American ideals, Frederick Douglass framed the women’s rights movement within the same revolutionary spirit that America was founded upon. He said:

The American doctrine of Liberty, is that governments derive their right to govern from the just consent of the governed, and declares that taxation without representation is tyranny, and the founders of the Republic went so far as to say that resistance to tyrants is obedience to God. On these principles woman no less than man has a right to vote. She has all the attributes that fit her for citizenship and a voter. Equally with man she is a subject of the law. Equally with man she is bound to know the law. Equally with man she is bound to obey the law. There is no more escape from its penalties for her than for him. When she commits crimes or violates the Law in any way, she is arrested, arraigned, tried, condemned, imprisoned like any other felon. Her womanhood does not excuse her from condign punishments. The Law takes no thought of her sex when she is accused of crime. Why should it take thought of her sex when bestowing its privileges? Plainly enough woman has a positive grievance. She is taxed without representation, tried without a jury of her Peers, governed without her consent, punished for violating laws she has had no hand in making. She may well enough ask as she does ask: Is this right?15

Frederick Douglass saw the women’s rights activists as patriotic Americans who were helping their country achieve its full potential. To him, the American flag, “Old Glory,” represented what America should be, and he connected the new and controversial idea of women’s rights to the American flag—a powerful symbol. He said, “Ever since George Washington and Betsy Ross put their heads together to evolve old glory, woman has been doing her part in lifting the nation up towards all Old Glory ought to signify.”16

Although Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Martin Luther King Jr. strategically connected new and controversial ideas to familiar and beloved American ideals and symbols, they were not being disingenuous. Their life’s work shows they truly believed in the American ideals of liberty and justice, and they really wanted the American flag to represent a nation of liberty and justice for all. Because oppression and injustice poisoned so many aspects of American society, they dedicated their lives to curing this poison and making the democratic ideals a reality for all people.

The Declaration of Independence is actually a visionary human rights charter. Inspired by the eighteenth-century European Enlightenment philosophers, the United States of America became the first country to ever be founded on such a bold declaration of human rights. But it was a document ahead of its time, because when our country was founded only wealthy landowners fully enjoyed the ideal of liberty. Fortunately for us, patriotic Americans such as Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Martin Luther King Jr., and countless others worked hard to bring America closer to its highest potential. To fulfill my responsibilities as an American citizen, I have a duty to continue this patriotic legacy by helping our country, to the best of my ability, make further progress. America has journeyed a long way toward the ideals of liberty, justice, and opportunity, but we still have a long way to go before these ideals truly become a reality for all Americans.

My existence is proof that progress is possible, because if a descendant of slaves can write these words today, why can’t our country keep moving in a positive direction? If we want to keep moving in a positive direction, however, we must be strategic and persuasive, just like the patriotic activists who came before us. But how can we promote the new and controversial idea of waging peace when the “worldview of waging war” has become the predominant worldview in America today? This worldview associates waging war with national security, freedom, safety, and even peace.

Because we live in a society where violence has become synonymous with strength, many Americans have the misconception that nonviolence means passivity and weakness. Many Americans also have the misconception that peace activists are unpatriotic hippies who are a threat to national security. With these misconceptions in the way, how can we show Americans that waging peace is a more effective way to solve our domestic and international problems than violence?

Waging peace is already a proud part of our American heritage, even though most of us don’t realize it. As I explained earlier, because democracy allows us to peacefully solve our problems without resorting to violence, “waging peace” is another way to say “practicing democracy.” Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Martin Luther King Jr. are just a few examples of the many patriotic Americans who waged peace through democratic struggle. In school I was taught that as American citizens we owe all of our freedom to war. But decades after the American Revolutionary War ended, the majority of Americans were still not free because most people in our country lacked the freedom to vote and other basic rights, and many Americans lived as slaves. When Americans used democratic struggle to gain their basic rights, they were in fact waging peace. But why was I not taught about the art of waging peace in school?

There are many other ways to connect the new and controversial idea of waging peace to the predominant worldview in America today. When discussing waging peace in my books and lectures, I often say I was inspired to wage peace by the warrior ideals and the education I received at West Point. I also reference democratic ideals such as liberty and justice, along with highly respected military veterans such as Douglas MacArthur, Dwight Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, and Smedley Butler, among many others.

Eisenhower and MacArthur were not only West Point graduates, war veterans, and generals, but they were also Republicans. It is difficult to call them naive, unpatriotic, or hippies. General MacArthur said, “If the historian of the future should deem my service worthy of some slight reference, it would be my hope that he mention me not as a Commander engaged in campaigns and battles . . . Could I have but a line a century hence crediting a contribution to the advance of peace, I would gladly yield every honor which has been accorded by war.”17

Martin Luther King Jr. and military veterans are among the most admired people in America today. Not only can we connect the new and controversial idea of waging peace to them, but we can also connect waging peace to the person many Americans see as the greatest genius who ever lived: Albert Einstein. A committed and lifelong peace activist, Einstein said, “It is my belief that the problem of bringing peace to the world on a supranational basis will be solved only by employing Gandhi’s method on a larger scale.”18

Even more importantly, we can also connect the new and controversial idea of waging peace to the person more Americans admire than anyone else: Jesus Christ, who is referred to in the Bible as the “Prince of Peace.” It is difficult to find a person in history who was a stronger advocate for peace than Jesus. I once saw a bumper sticker that asked WHO WOULD JESUS BOMB? Gandhi said, “Jesus was the most active resister known perhaps to history. This was non-violence par excellence.”19

When the issue of peace is concerned, Jesus told us to love our enemies, not judge others, and be peacemakers. In the Sermon on the Mount, he said, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God . . . You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth . . .’ [But] if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also . . . You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you . . . Do not judge, or you too will be judged.”20

General Omar Bradley admired the peaceful ideals expressed by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount. After the devastation of World War II and rise of the nuclear arms race, he realized that Jesus’s peaceful ideals were more important than ever before. In a 1948 speech, General Bradley said, “We have grasped the mystery of the atom and rejected the Sermon on the Mount . . . The world has achieved brilliance without wisdom, power without conscience. Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants.”21

General MacArthur, who was in charge of rebuilding Japan after World War II, also admired Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. During the occupation of Japan, MacArthur’s priorities included giving Japanese women the right to vote, promoting religious freedom, and spreading the ideals expressed in the Sermon on the Mount. He said:

I am a Christian and an Episcopalian, but I believe in all religions. They may differ in form and ritual, but all recognize a divine Creator, a superior power, that transcends all that is mortal . . . Should I, with my full military power, arbitrarily decree the adoption of the Christian faith as a national religion [in Japan]? . . . The solution I adopted . . . was to befriend all religions; to permit complete freedom of religious worship as individuals might choose; to free all creeds—Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian—from any Government . . . The concept of Christ that man should do what is right, even if it entailed personal sacrifice, that the urge of conscience was greater than any material reward, was something new and novel . . . If the lessons of the Scriptures of the Sermon on the Mount could be integrated and welded into their own religious cultures, if basic spirituality could be common to all, it would mean little whether a Japanese were a Buddhist, a Shintoist, or a Christian.22

Although Christianity is a complex religion that is interpreted in many different ways, the abolition of war can certainly be connected to the Christian worldview, because peace is a central part of Jesus’s teachings. Christianity was originally a peace-loving religion. When people tell me the majority of Americans will never reject war as a method of conflict resolution, I often say, “If Jesus—who is admired by more Americans than any other person—was a peace activist, isn’t it possible that a large number of Americans might someday support the abolition of war?” Of course this will not be easy, because we must first achieve spiritual change before we can become less judgmental and love our enemies as Jesus, Martin Luther King Jr., Gandhi, and other great peacemakers did. Spiritual change requires us to heal our inner wounds and increase our empathy through personal growth and transformation. When we achieve spiritual change, we become more effective warriors in the struggle for peace, justice, and the abolition of war.

Connecting a new and controversial idea to powerful ideals within someone’s worldview means nothing if the truth is not on our side. For example, connecting the new and controversial idea of racial and gender equality to the Declaration of Independence would have meant nothing if African Americans and women were in fact intellectually and morally inferior to white men. Most Americans used to believe this myth of inferiority, but the truth was on the side of the advocates for racial and gender equality, because it is a scientific fact that African Americans and women are not intellectually and morally subhuman. In a similar way, oppressors throughout history have misused the Bible to justify many unjust policies such as slavery, the oppression of women, and even the persecution of Galileo. But Galileo, along with the advocates for racial and gender equality, had the truth on their side. When we question and think critically, the sword of truth allows us to cut through layers of deception and heal the wounds of oppression and injustice.

It is important to question and think critically. I don’t agree with every opinion expressed by MacArthur or Gandhi. When anyone walks the path of truth, it is common to stumble and even make wrong turns. To reference a quote I used in chapter 2, after Malcolm X learned the truth of human brotherhood, he said, “Well, I guess a man’s entitled to make a fool of himself if he’s ready to pay the cost. It cost me twelve years. That was a bad scene, brother. The sickness and madness of those days—I’m glad to be free of them . . . The cause of brotherhood [is] the only thing that can save this country. I’ve learned it the hard way—but I’ve learned it.”23 I quote many people who searched for truth and understanding just as we are. We should be grateful to them, because learning from their victories and failings can help us better navigate the path of truth.

I have learned a great deal from others who walked the path of truth, and in this book I focus less on opinions and more on evidence, logic, and facts. My ideas about waging peace and the abolition of war have less to do with religious beliefs and a lot more to do with scientific evidence showing that human beings are not naturally violent and war is not inevitable. By offering abundant evidence from military history, psychology, and many other subjects, my books show the numerous ways human beings can be conditioned to be extremely violent. But my books also show that we are not born with a natural urge to maim and kill our own species.

Gandhi lacked much of the evidence we have today, but he said that if human beings are in fact naturally violent, his entire philosophy of nonviolence falls to pieces. Gandhi said, “If love or non-violence be not the law of our being, the whole of my argument falls to pieces . . . It is the law of love that rules mankind. Had violence, i.e., hate, ruled us, we should have become extinct long ago.”24 Gandhi called love the “law of our being,” and earlier in this book I showed that even armies must create love between soldiers to make them fight most effectively, and every aggressive empire in history claims it is fighting for self-defense and peace.

Thomas Merton said, “Gandhi firmly believes that non-violence is actually more natural to man than violence. His doctrine is built on this confidence in man’s natural disposition to love. However, [when] man finds himself deeply wounded . . . his inmost dispositions are no longer fully true to themselves.”25

By understanding how Gandhi, Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Martin Luther King Jr., and many others successfully waged peace, we can improve on their techniques. This allows us to apply the strategic principles of persuasion to a wide variety of new and controversial ideas. To offer a recent example, the new and controversial Occupy Wall Street movement began in 2011. Although it was initially framed by its opponents and many within the movement as a struggle against corporations and the rich, it is more persuasive to frame the Occupy movement as a struggle for fairness, justice, and democracy. In a similar way, Martin Luther King Jr. did not frame the civil rights movement as a struggle against white people, but as a struggle for fairness, justice, and democracy. Our message becomes more effective when we are for something rather than against something.

Although some in the Occupy movement are still framing it as a struggle against corporations and the rich, there are many reasons why it is more effective and accurate to frame the movement as a struggle for fairness, justice, and democracy. Here is one way I would frame the Occupy movement: The problem isn’t that corporations are making a profit, but that so many of them are focused on maximizing profit with no regard for the well-being of our country and health of our planet. I think corporations should be allowed to make computers and other useful products, but I don’t think they should be allowed to buy politicians with massive campaign contributions. Democracy is supposed to be a system where one person equals one vote, not one dollar equals one vote.

I have heard opponents of the Occupy movement say, “Those protestors are hypocrites, because they want to destroy corporations, yet they use cell phones, laptops, Google, and Facebook.” But by framing the Occupy movement around ideals such as fairness, justice, and democracy, a person can respond by saying, “This is not about corporations making things. It’s about fairness, justice, and democracy. It’s about reducing the influence of money in politics, because the influence of money in our political system damages fairness, justice, and democracy.” As long as corporate money has so much control over our democratic system, it becomes more difficult for American citizens to make meaningful progress on issues such as peace, environmental sustainability, and worker’s rights, because these issues often threaten the maximization of corporate profits.

The Occupy movement can also be connected to Martin Luther King Jr., who is widely admired in America today. If King had not been assassinated, he would have begun the Occupy movement decades ago. King had a vision called the Poor People’s Campaign, which was a plan to occupy Washington, DC, and pressure the U.S. government to create fairness and justice in our political and economic system. Samuel Kyles, a minister who worked closely with King and was with him during the last hour before his assassination, said: “With the Poor People’s Campaign, Martin is talking about taking these poor people to Washington, build tents, and live on the [Washington] mall until this country did something about poverty . . . Can you imagine what would happen if all these black and white and brown people go to Washington and build tents and live in tents in Washington?”26

King’s plan to occupy Washington, DC, differed from the Occupy movement in several ways. Many members of the Occupy movement originally resisted the idea of making demands, but King saw demands as a necessary means of applying political pressure. King also emphasized the importance of detailed strategic planning and thorough training. In fact, King wanted the activists involved in a nonviolent occupation movement to undergo three months of training, since this challenging struggle would strain their patience, compassion, hope, and willpower.

Nonviolence strategist Gene Sharp has criticized the Occupy movement for its lack of planning. A New York Times article stated: “Sharp emphasizes in all his work the need for preparation and care, and he says that not all nonviolent movements work. Occupy Wall Street did not have a plan, he says, which was its downfall. ‘It’s well intentioned,’ he says, ‘but occupying a small park in downtown New York is pure symbolism. It doesn’t change the distribution of wealth.’”27

Gene Sharp did not critique the Occupy movement to be mean, but because he wants activists to learn, adapt, and succeed. Unlike Sharp, I am not ready to say the Occupy movement has failed, and I think it has had some impact. I have been impressed with many people in the movement, and I don’t see any reason why they cannot adapt and succeed. Humanity needs people willing to struggle for peace and justice, and those within the Occupy movement still have a lot of potential to help solve our national and global problems. By critiquing their own actions, they can adapt by taking their strategy and training to a new level, as King did.

King put a great deal of thought into the steps necessary for a successful nonviolent occupation, and if he had not been assassinated in 1968 at the age of thirty-nine, he and many other Americans would have camped in Washington, DC, while creatively, strategically, and persistently waging peace. In the following excerpt from a 1967 speech, King explained the detailed strategic planning and thorough training that are necessary to make a nonviolent occupation movement succeed:

For the 35 million poor people in America—not even to mention, just yet, the poor in the other nations—there is a kind of strangulation in the air. In our society it is murder, psychologically, to deprive a man of a job or an [adequate] income. You are in substance saying to that man that he has no right to exist. You are in a real way depriving him of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, denying in his case the very creed of his society. Now, millions of people are being strangled that way. The problem is international in scope. And it is getting worse, as the gap between the poor and the “affluent society” increases [emphasis added] . . .

Beginning in the New Year, we will be recruiting three thousand of the poorest citizens from ten different urban and rural areas to initiate and lead a sustained, massive, direct-action movement in Washington. Those who choose to join this initial three thousand, this nonviolent army, this “freedom church” of the poor, will work with us for three months to develop nonviolent action skills. Then we will move on Washington, determined to stay there until the legislative and executive branches of the government take serious and adequate action on jobs and income. A delegation of poor people can walk into a high official’s office with a carefully, collectively prepared list of demands. (If you’re poor, if you’re unemployed anyway, you can choose to stay in Washington as long as the struggle needs you.) And if that official says, “But Congress would have to approve this,” or, “But the President would have to be consulted on that,” you can say, “All right, we’ll wait.” And you can settle down in his office for as long a stay as necessary.

If you are, let’s say, from rural Mississippi, and have never had medical attention, and your children are undernourished and unhealthy, you can take those little children into the Washington hospitals and stay with them there until the medical workers cope with their needs, and in showing [Washington] your children you will have shown this country a sight that will make it stop in its busy tracks and think hard about what it has done. The many people who will come and join this three thousand, from all groups in the country’s life, will play a supportive role, deciding to be poor for a time along with the dispossessed who are asking for their right to jobs or income . . . Why camp in Washington to demand these things? Because only the federal Congress and administration can decide to use the billions of dollars we need for a real war on poverty.28

Without strategy and training, nonviolent movements can easily descend into rioting. This occurred in Occupy Oakland, a spin-off of the Occupy Wall Street movement. King said the following about riots: “There is something painfully sad about a riot. One sees screaming youngsters and angry adults fighting hopelessly and aimlessly against impossible odds. Deep down within them you perceive a desire for self-destruction, a suicidal longing . . . [During the civil rights movement] nowhere have the riots won any concrete improvement such as have the organized protest demonstrations.”29

The Poor People’s Campaign did in fact occupy Washington, DC, after King’s death, but the encampment was problematic and had strayed from his plan of a massive and organized civil disobedience campaign. The failure of the encampment during the Poor People’s Campaign has caused people to question the very tactic of nonviolent occupation, but the Bonus Marchers (whom I discuss in Will War Ever End?) were able to successfully implement this tactic during the 1930s. The Bonus Marchers were World War I veterans who protested during the Great Depression for the wages the U.S. government owed to them, and King based his plan on their successful nonviolent occupation campaign. Why were the Bonus Marchers successful? Because they had lived in encampments while serving in the military, were they better prepared to live and work together in the difficult circumstances of an encampment?

King recognized the inherent difficulty of nonviolent occupation by saying, “This is not an easy program to implement. Riots are easier just because they need no organization. To have effect we will have to develop mass disciplined forces that can remain excited and determined without dramatic conflagrations.”30 Activists should discuss which tactics are most likely to be effective in the twenty-first century, while remembering that these tactics must strategically apply pressure and persuasively promote a “true revolution of values.” King described how a true revolution of values would cause us to question many of America’s domestic and foreign policies:

A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies. On the one hand we are called to play the Good Samaritan on life’s roadside, but that will be only an initial act. One day we must come to see that the whole Jericho Road must be transformed so that men and women will not be constantly beaten and robbed as they make their journey on life’s highway. True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.

A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. With righteous indignation, it will look across the seas and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa, and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries, and say, “This is not just.” . . . A true revolution of values will lay hand on the world order and say of war, “This way of settling differences is not just.” . . . A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death. America, the richest and most powerful nation in the world, can well lead the way in this revolution of values.31

I currently teach many kinds of workshops, including a workshop on persuasion and strategic thinking. One method I teach in this workshop is “connecting a new and controversial idea to powerful ideals within someone’s worldview,” which can strengthen the message of any just cause. When my own work is concerned, waging peace and the abolition of war are new and controversial ideas—at least in the minds of most Americans. But in my books and lectures I make dozens of connections between these new ideas and the predominant worldview in America. The following diagram shows how the Occupy movement in its beginning could have made its message more persuasive to the majority of Americans. I have only scratched the surface in terms of the many connections that could have been made, and many more boxes could be added to the diagram:

Figure 10.2. How the Occupy movement could have been connected to the powerful ideals contained in the predominant American worldview in 2011

There are strategically minded people in the Occupy movement who are framing the movement around ideals such as fairness, justice, and democracy rather than an “us versus them” mentality; just as King said it’s not about black versus white, it’s about our highest ideals. But as I am writing this there has not yet been a strategic consensus within the Occupy movement to ensure it has the most persuasive message possible. The people who were drawn to the Occupy movement in 2011 were mostly those who already agreed with it, but a movement’s success is actually determined by its ability to reach beyond the choir and persuade those who do not agree with it.

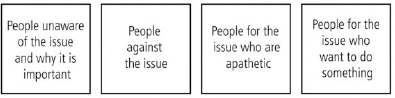

How can we do more than preach to the choir? By thinking strategically, we can optimize our message in a way that will magnify its impact. Whether the issue is women’s rights, racial equality, peace, protecting the environment, the humane treatment of animals, or creating fairness and justice in our political system, every movement must interact with four kinds of people.

Figure 10.3 The Four Kinds of People Every Movement Must Interact With

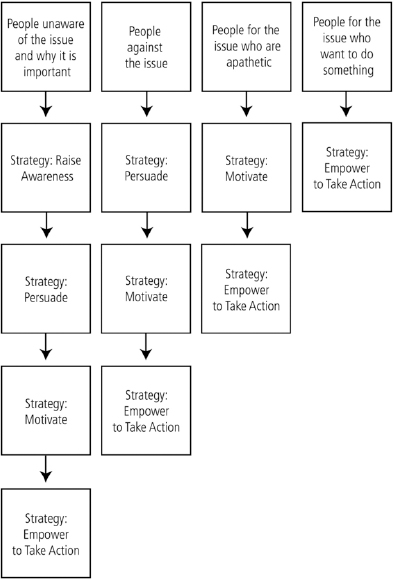

To promote any issue that has truth and justice on its side, we must influence these four kinds of people. But how can we do this? We can influence these people and move them toward action by using four strategies: raise awareness, persuade, motivate, and empower. The following diagram shows how these four strategies allow us to influence the four kinds of people every movement must interact with.

Figure 10.4 The Four Strategies for Moving People Toward Action

If your movement is trying to promote justice but the majority of people do not realize injustice is occurring, they must first be made aware before they can be persuaded, motivated, and empowered to take action. And if people disagree with your point of view, they cannot be motivated or empowered to take action in support of your cause unless they are first persuaded. Likewise, people cannot be empowered to take action unless they are first motivated to do something.

Lack of motivation is a major reason why progress does not happen. Henry David Thoreau said, “There are thousands who are in opinion opposed to slavery and war who yet do nothing to put an end to them. There are nine hundred and ninety-nine patrons of virtue to every virtuous person.”32 According to Thoreau, for every thousand people who think something is a good idea, only one person has the motivation to actually do something about it. This is not just Thoreau’s viewpoint. It is also a fact of history. Less than one percent of Americans were actively involved in the women’s rights movement or the civil rights movement.

How do we motivate people to take action? The most effective way to motivate people to wage peace is not by appealing to their hatred and fear (which lead to war), but by appealing to their compassion, conscience, hope, and reason. I discuss how we can motivate people to wage peace in the “moral fury” chapter of The End of War and the hope, empathy, appreciation, conscience, and reason chapters of Peaceful Revolution. When we motivate people to wage peace, it is also very important to empower them. During my lectures a common question people ask me is, “I am motivated to do something and I want to take action, but I don’t know what I can do to make a difference.” To help these people transform their motivation into action, we must empower them with waging peace strategies and tactics.

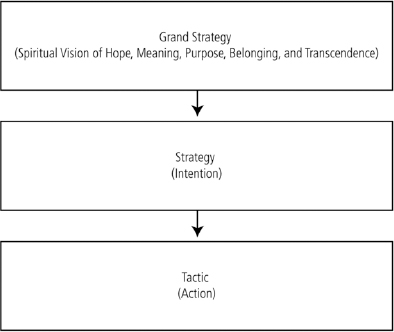

When waging peace is concerned, what is the difference between strategy and tactics? Strategy is the intention, while tactics are the actions. When people wage peace together, they are like an orchestra playing beautiful music together. Strategy is a tune you hum in your head. It is a melody written on paper. It is a song waiting to be heard. Tactics bring the music of strategy to life.

Examples of tactics (actions) include protests, petitions, boycotts, and spreading new ideas that transform how people think. When we perform any tactic (action), we should ask what our strategy (intention) is. Are we trying to raise awareness, persuade, motivate, empower, or all of the above? Nonviolence strategist Gene Sharp lists 198 tactics people have used in nonviolent movements around the world, but I encourage you to question the tactics on his list. Although most of them are useful and effective, some will actually hurt your cause. For example, number 30 on his list is “rude gestures,” but these disrespectful actions are more likely to hurt rather than help your movement. If someone had taken a picture of Martin Luther King Jr. flipping off a group of white people with his middle finger, it would have greatly harmed the civil rights movement by reducing the moral authority not only of King, but the entire movement.

Just as a few instruments playing out of tune can turn the beautiful music of an orchestra into noise, a thoughtless tactic not based on effective strategy can hurt an entire movement. If someone bombs a corporate building in the name of “peace” or “protecting the environment,” it can damage the work of everyone associated with the movement. It also gives government officials an excuse to use violence against the protestors in the name of “selfdefense,” “national security,” and “fighting terrorism.” Activist Blase Bonpane says, “If anyone in your movement advocates violence, always assume they are an undercover government agent.”33 Governments have been known to plant undercover agents who advocate violence in social movements, because when a movement becomes violent it loses its moral authority and its members can be labeled as “terrorists.” Now the government can take the gloves off and fight you where it is strongest: the realm of violence. Journalist Seth Rosenfeld, from the Center for Investigative Reporting, tells us:

The man who gave the Black Panther Party some of its first firearms and weapons training—which preceded fatal shootouts with Oakland police in the turbulent 1960s—was an undercover FBI informer, according to a former bureau agent and an FBI report. One of the Bay Area’s most prominent radical activists of the era, Richard Masato Aoki was known as a fierce militant who touted his street-fighting abilities. He was a member of several radical groups before joining and arming the Panthers, whose members received international notoriety for brandishing weapons during patrols of the Oakland police and a protest at the state Capitol. Aoki went on to work for 25 years as a teacher, counselor and administrator at the Peralta Community College District, and after his suicide in 2009, he was revered as a fearless radical.

But unbeknownst to his fellow activists, Aoki had served as an FBI intelligence informant, covertly filing reports on a wide range of Bay Area political groups, according to the bureau agent who recruited him. That agent, Burney Threadgill Jr., recalled that he approached Aoki in the late 1950s, about the time Aoki was graduating from Berkeley High School. He asked Aoki if he would join left-wing groups and report to the FBI. “He was my informant. I developed him,” Threadgill said in an interview. “He was one of the best sources we had . . .” The FBI later released records about Aoki in response to a federal Freedom of Information Act request made by this reporter. A Nov. 16, 1967, intelligence report on the Black Panthers lists Aoki as an “informant” with the code number “T-2.”34

In his book Subversives, Seth Rosenfeld provides more information about the harm caused by Aoki: “He had given the Black Panthers some of their first guns and weapons training, encouraging them on a course that would contribute to shootouts with police and the organization’s demise [emphasis added]. And during the Third World Strike, he encouraged physical confrontations that prompted Governor Reagan to take the most severe law-enforcement measures against the Berkeley campus yet [emphasis added]—ones that ultimately would have fatal consequences.”35

When people in a social movement use violent tactics they severely damage their own cause. But even peaceful tactics, if they are not strategic, can be counterproductive and damaging to a cause. An example is an Occupy movement protestor who was photographed defecating on a police car. The photograph was widely circulated to discredit the Occupy movement, and I cannot count the number of times I have heard opponents of the Occupy movement refer to the protestors as “dirty hippies” or “filthy bums who need to occupy a shower.”

During the civil rights movement, the activists used strategic thinking to anticipate how they would be criticized. They knew that their opponents would call them “dirty,” so they took proactive steps to protect themselves from this criticism. Diane Nash, an African American student at Fisk University who participated in the Nashville sit-ins, said, “We spent many, many hours anticipating some of the opposition, and we knew . . . they would say, ‘We don’t want to sit next to dirty people while we have lunch.’ And so one of the ways we combated that was by having a dress code.”36

When the Occupy movement began, the criticisms against it were easy to predict. The protestors would be called “dirty hippies,” “lazy bums who don’t want to get a job,” and “spoiled kids with a sense of entitlement who want government handouts.” I have met many people in the Occupy movement who are hard-working Americans from all walks of life, but it is difficult for the American people to know this when the protestors are being stereotyped as dirty, lazy, and entitled. Whenever we wage peace, we should expect to be criticized, but we should make ourselves as difficult a target as possible. We should not make it easy for our critics by dressing and acting exactly as they have negatively stereotyped us, giving them abundant ammunition to attack us with.

During peace protests, some activists dress and behave in a way that reinforces the unfair stereotype of the “dirty hippie.” But Martin Luther King Jr. discussed the importance of not dressing in a “comic display of odd clothes” that reinforces negative stereotypes, because it distracts from the core message and makes it easier for opponents of the movement to dismiss the activists’ important message. Regarding the march on Washington in 1963, King said, “The stereotype of the Negro suffered a heavy blow. This was evident in some of the comment, which reflected surprise at the dignity, the organization and even the wearing apparel and friendly spirit of the participants. If the press had expected something akin to a minstrel show, or a brawl, or a comic display of odd clothes and bad manners, they were disappointed.”37

When King used the phrase “comic display of odd clothes,” he was aware of the fact that the media will photograph and publish pictures of the most outrageously dressed activists they can find, which serves to discredit their movement. But when civil rights protestors wearing church clothes were shown on national television being assaulted by mobs, blasted with fire hoses, and attacked by police dogs, it had a much stronger impact on the American people than if the protestors had been wearing outlandish outfits or very casual clothing. If I want to wear shorts and flip-flops during my spare time that is fine, but I would not wear such casual clothing when lecturing at a university or participating in a public protest. People can wear whatever they want in their daily lives, but I encourage all activists to consider how adopting a dress code during a protest can make their message more persuasive to those who disagree with them.

A dress code does not have to be overly complicated, because even a simple act such as not wearing sunglasses can make a big difference. I advise activists to never conceal their eyes or any other part of their face during a protest, because when people cannot see our face they also cannot see our humanity. As I mentioned in chapter 3, the army taught me to take off my sunglasses when speaking with people in the Middle East, because so much of our humanity and trustworthiness is expressed through our eyes. As I discuss in Peaceful Revolution, it is also much easier to dehumanize and kill people when we cannot see their faces.

In his groundbreaking book On Killing, Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman explains that when people’s faces are concealed, it is much easier to hurt them and justify our hostile actions:

Looking in a man’s face, seeing his eyes and his fear, eliminate denial [of his humanity] . . . Instead of shooting at a uniform and killing a generalized enemy, now the killer must shoot at a person and kill a specific individual. Most [human beings] simply cannot or will not do it . . .

It seems that soldiers intuitively understand that when they turn their backs, they are more apt to be killed by the enemy . . . This same enabling process explains why Nazi, Communist, and gangland executions are traditionally conducted with a bullet in the back of the head, and why individuals being executed by hanging or firing squad are blindfolded or hooded. And we know from Miron and Goldstein’s 1979 research that the risk of death for a kidnap victim is much greater if the victim is hooded. In each of these instances the presence of the hood or blindfold ensures that the execution is completed and serves to protect the mental health of the executioners. Not having to look at the face of the victim provides a form of psychological distance that enables the execution party and assists in their subsequent denial and the rationalization and acceptance of having killed a fellow human being.

The eyes are the window of the soul, and if one does not have to look into the eyes when killing, it is much easier to deny the humanity of the victim. The eyes bulging out “like prawns” and blood shooting out of the mouth are not seen. The victim remains faceless, and one never needs to know one’s victim as a person.38

James Lawson, a civil rights leader whom Martin Luther King Jr. called “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world,” said we must allow people to see our eyes and face when we wage peace. Lawson explains, “It had much more meaning to the attacker if, as he strikes you on the cheek you are looking him in the eyes.”39 Covering our face makes us appear less peaceful and more intimidating, which is one reason why members of the Ku Klux Klan often cover their faces with hooded masks. Also, covering our face gives us a sense of anonymity, making us more likely to engage in mob violence.

Many protestors feel the need to wear gas masks during protests, but this makes them look like aliens from another planet. If government officials unjustly use tear gas against peaceful protestors, the protestors should capture it on camera so the American people can witness this injustice. The image of pain on a woman’s face as she chokes on tear gas is much more disturbing to the American public than the image of someone being attacked whose face (and humanity) is concealed by a gas mask, which creates a non-human and alien appearance. In the army we had to be tear-gassed during basic training. It is uncomfortable, but Gandhi said nonviolent activists must be willing to suffer and die for their cause. To many peace activists I know, being tear-gassed is a small price to pay when they are willing to die for a cause.

If we conduct a protest while wearing a gas mask or outlandish costume, it is easier for those who disagree with us to dehumanize us or dismiss us as “crazy.” The dress code of the civil rights protestors minimized barriers between them and the American public, making it easier for many Americans to see them as human beings with dignity. When the black sanitation workers in Memphis—who lived in extreme poverty—protested during the civil rights movement for fair wages and equal treatment, they had a dress code. They also wore a sign that read I AM A MAN.

When the diverse instruments in an orchestra are on the same sheet of music, they can create beautiful music. Strategy puts the diverse people in a movement on the same sheet of music, allowing them to create beautiful and effective actions. If we want to play the melody of waging peace so that the whole world can hear it, we must be strategic, organized, and disciplined. James Lawson explains, “You cannot go on a demonstration with twentyfive people doing whatever they want to do. They have to have a common discipline, and that’s a key word for me . . . The difficulty with nonviolent people and efforts is that they don’t recognize the necessity of fierce discipline, and training, and strategizing, and planning, and recruiting, and doing the kinds of things to have a movement.”40

James Lawson, Gandhi, and King all understood that disciplined teamwork is essential when waging peace. Disciplined teamwork is necessary to accomplish any challenging goal, whether it is waging peace as a nonviolent movement, performing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as a large orchestra, making a film involving hundreds of people, winning the Super Bowl as a team of athletes, or putting a man on the moon. In Peaceful Revolution I discuss how discipline can greatly improve our quality of life and ability to wage peace.

When we are outnumbered by a much larger opponent—as nonviolent movements always are when challenging injustice—disciplined teamwork becomes even more important. Naganuma Muneyoshi, a seventeenth-century Japanese military scientist, explained: “A disciplined army can beat an undisciplined army even three to five times its size. Suppose there is a huge boulder that dozens of men cannot roll. Now, if one man gives a call so that the group responds in unison, pushing at once, even a few men can move it. There is no technique to this but coordinating efforts as one . . . Disciplined order is a means of coordinating energetic force and momentum . . . If you gain victory without discipline, this should be called being lucky you didn’t lose.”41

Although discipline and strategy are crucial, there is also a concept in the military called grand strategy. When waging peace is concerned, I define grand strategy as the overarching spiritual vision that guides a movement. The most effective social movements are also spiritual movements. The word “spiritual” does not have to mean “religious.” When I use the word “spiritual,” I am referring to a movement’s ability to give people a sense of hope, meaning, purpose, and belonging. I am also referring to a movement’s ability to help people transcend their personal desires in order to identify with high ideals, all of humanity, and even all life.

Figure 10.5 Grand Strategy

Why is a spiritual vision that gives people a solid foundation of hope, meaning, purpose, belonging, and transcendence so important to a movement? This foundation nurtures spiritual change within us, giving us the inner strength to overcome the most significant obstacles. In the army I heard a saying: “A human being can survive for a few weeks without food, a few days without water, but only a few moments without hope.” A person with absolutely no hope at all would be depressed and suicidal. If we do not have at least a little hope, it is difficult to get out of bed in the morning.

Hope is as vital for human survival as food and water. People are drawn to a message of hope, and this is one reason why Martin Luther King Jr. was so effective. King had the amazing ability to talk about something bad like racism and make people feel good, but many activists today tend to talk about something good like peace and make people feel bad. As one of my friends in the peace movement told me half jokingly, “Whenever I go to a lecture on peace, the speaker usually makes me feel so depressed about the state of our country and the world that I want to go home and shoot myself.” King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, even though it is about racism and segregation, is one of the most hopeful and inspiring speeches I have ever read. King could give a speech about tragic subject matter, but frame it in a way that made people feel more hopeful afterward.

King’s hope is even more remarkable when we consider the terrible conditions that surrounded him. He had many reasons to be hopeless and hateful, because black people were being murdered by the supporters of segregation and he was receiving daily death threats—where people threatened to not only kill him but also his wife and children. The death threats became real when his house was bombed in 1956. His wife and children, who were in the house when the bombing occurred, were fortunate to survive the attack. These bombings were directed not only at him and his family, but at civil rights advocates throughout the South. In 1963 King said, “Local racists [in Birmingham] have intimidated, mobbed, and even killed Negroes with impunity . . . From the year 1957 through January of 1963, while Birmingham was still claiming its Negroes were ‘satisfied,’ seventeen unsolved bombings of Negro churches and homes of civil-rights leaders had occurred.”42

Today we would call these bombings terrorism, but King did not allow terrorism to transform him into a hateful human being. Whether he was discussing racism and segregation, or war and American foreign policy, King always found a way to give people realistic hope. Speaking truthfully without hatred or cynicism, he ended his 1967 speech “Beyond Vietnam” by saying:

Now let us begin. Now let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter, but beautiful, struggle for a new world . . . And if we will only make the right choice, we will be able to transform this pending cosmic elegy into a creative psalm of peace. If we will make the right choice, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our world into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. If we will but make the right choice, we will be able to speed up the day, all over America and all over the world, when justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.43

King’s hope was not based on naive and wishful thinking, but realistic reasons to be hopeful and not surrender to despair. In Peaceful Revolution I describe how we can base our hope on realism. It is important for activists to understand the power of hope, because just as a military unit must feed its soldiers with food and water, we must feed a movement with hope, meaning, purpose, belonging, and transcendence. And just as a military unit must train its soldiers to wield the weapons of war, we must train activists to wield a far more powerful weapon. Gandhi called it “the sword of love,” I call it “the sword of truth,” and King called it “the sword that heals.”