North Fork of the Big Thompson Trail System

Everyone is destination oriented. This trail guide of necessity reflects the hiker’s obsession with getting to a particular place. But on the North Fork trail system there is much to be said for no-particular-destination hiking. Most destinations are far from the trailhead. The national park itself is 4.4 miles from the starting point in Roosevelt National Forest.

The land around the North Fork of the Big Thompson River has been less used for day hiking than other sections of the park—Bear Lake or Glacier Gorge, for instance—because of the long distances to specific destinations. It was the North Fork’s remoteness that attracted one of the most colorful characters in Estes Park history in the 1870s. The Earl of Dunraven, an Englishman, had attempted to gain control of the Estes Park region to preserve its beauty and wildlife from despoliation by the three or four summer tourists who drifted in weekly. By fraudulent means, Dunraven gained title to enough land to turn Estes Park and the entire Big Thompson drainage to the north, west, and south (including the North Fork) into his own private hunting reserve.

When Americans paid no attention to his titles, land or otherwise, Dunraven saw that his plan would fail. He reversed his goals and opened a posh hotel to capitalize on the growing fame of Estes Park as a summer paradise. Meanwhile, he escaped the frustrations of civilization by building a hunting lodge for himself along the North Fork.

Dunraven’s name lives on in a glade, trail, mountain, and lake in the North Fork drainage. His memory adds romance to an area that would be very pleasant and interesting even without a colorful history. The day hiker on the way to nowhere in particular will have an enjoyable trip along the North Fork.

To reach the trailhead, drive north from Estes Park on the Devils Gulch Road to the little town of Glen Haven. At a Forest Access sign about 2 miles past Glen Haven, turn left on unpaved Dunraven Glade Road. Somewhere along this road is the now-lost site of Dunraven’s hunting lodge. Perhaps some day excavation for the construction of a new home will turn up the whiskey cache that the earl buried one fall and was unable to find the following spring.

A few miles down the unpaved road on the left-hand side is the Dunraven Glade Trailhead parking lot provided by the USDA Forest Service. On the other side of the parking lot, the Dunraven Trail begins by heading up a small ridge to enter Comanche Peak Wilderness. The path soon drops steeply down a forested slope to parallel the North Fork. To the left the trail extends down through a deep, narrow canyon to Glen Haven—an easy, pleasant walk of less than 2.0 miles. To the right the trail extends much farther—not all easy, but mostly pleasant.

Passage to the right does start out easily through the shade of thick blue spruce and Douglas-fir. In late August and early September, you may have trouble walking quickly past raspberry bushes laden with delicious fruit. As this beautiful canyon widens, the trail passes from national forest property to private land. While you are on private property, be especially conscientious about staying on the trail.

Before long, you find yourself walking on a four-wheel-drive road, which narrows again to trail dimensions until breaking out of the trees at Deserted Village, 3.0 miles from the trailhead. Wagons carried hunters to this turn-of-the-twentieth-century resort. A dysentery epidemic in 1909 had a poor effect on business, and the place was abandoned once and for all by 1914. The earl’s hunting parties called this site Dunraven Meadows; a 1907 map labeled it Dunraven Park.

Lest you duplicate the unpleasant intestinal symptoms of wilderness visitors in 1909, do not drink the water straight from the North Fork. Treat it chemically and/or boil it first.

Ponderosa pines close in on the trail as the meadow narrows toward its upper end. Some of them have grown around strands of barbed wire that used to fence off someone’s land interest. Dunraven probably did not bother to erect fences along the North Fork; people ignored his other fences anyway, running cattle over much of the land he claimed. His dream of preserving the wilderness and its wildlife for himself was a $200,000 flop. After one last hunt up the North Fork in 1880, he left the region for good. Preservation along a more typical American pattern was accomplished in 1915 with the establishment of Rocky Mountain National Park.

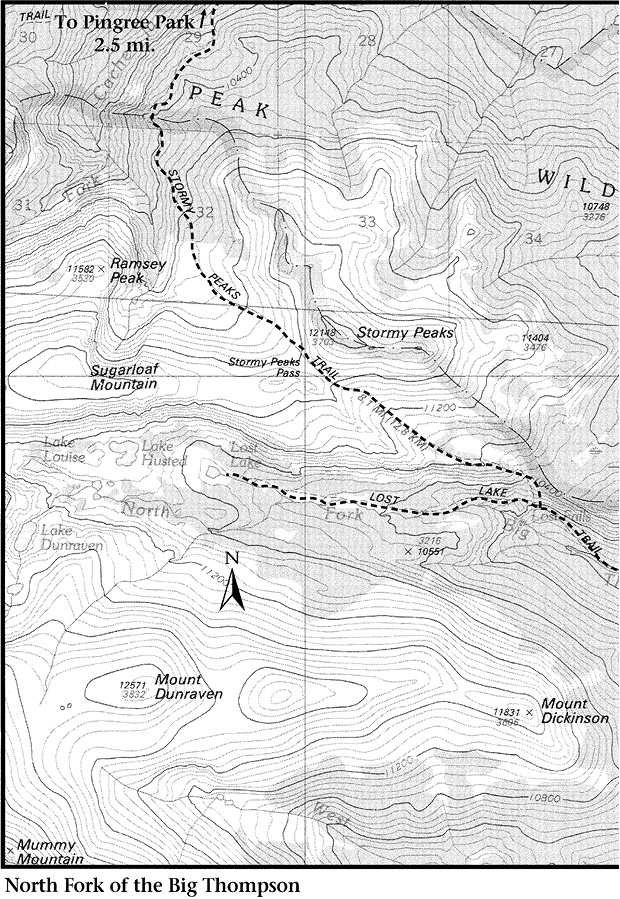

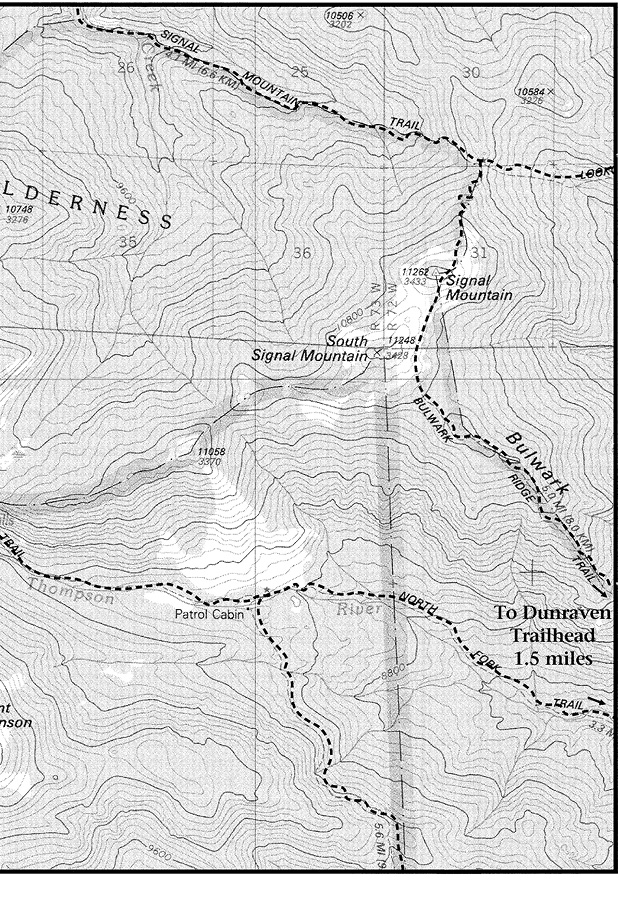

Almost 1.0 mile inside the park border, the North Boundary Trail begins on the left. Despite its name, it follows the eastern boundary south to Cow Creek Trailhead. This trail passes the North Fork patrol cabin less than 200 yards from its junction with the Dunraven Trail.

Past the junction, the trail along the North Fork is called the Lost Lake Trail. It proceeds along the bottom of the valley on a fairly mild grade for about 1.5 miles, then climbs steeply away from the river. At a spot 2.3 miles from the North Fork patrol cabin, the trail forks. The Stormy Peaks Trail (see page 52) is the right-hand fork. The Lost Lake Trail continues left over a relatively young terminal moraine, missing Lost Falls but passing through Lost Meadows. It parallels the creek to reach Lost Lake.

Lost Lake itself was once lost to the national park. After Dunraven gave up his dream, the need for preserving the area became evident. In 1911 a dam was built on the North Fork, enlarging Lost Lake into a reservoir. The NPS acquired the reservoir in the early 1970s and demolished the dam in 1985. Human alteration of the lake now is limited to the “bathtub ring” where high water killed the plants.

The National Park Service does not maintain a trail beyond Lost Lake, but easy routes exist to goals further on. Take care to avoid damage to this high-altitude wilderness by intense vegetation trampling. Two lovely, unnamed alpine lakes sit on the other side of a ridge southwest of Lost Lake. There you are close to the base of Rowe Peak, and the rock cliffs of the mountains rise dramatically from the tundra.

The North Fork descends into the upper lake via a small noisy waterfall tumbling out of an interesting gorge that extends down from Lake Dunraven. Rather than climbing the gorge to Lake Dunraven, you may prefer to use it for your descent; a much easier route to the earl’s lake begins at the outlet of the lower of the two unnamed lakes. After crossing the outlet, worm your way through the least dense section of krummholz, traverse the bottom of a talus slope, and then head straight up the ridge that hides Lake Dunraven.

To climb Mount Dunraven, continue up the ridge. After it becomes somewhat less steep, descend slightly and cross an unnamed drainage to reach and then ascend the main bulk of Dunraven. Dunraven is the first summit on a spur extending east from the Mummy Range. The second is unnamed and in the way if you wish to continue along the spur to Mount Dickinson, at the end.

From the Mount Dunraven spur, you can climb to a saddle on the main section of the Mummy Range between Hagues Peak and Mummy Mountain. Although the approach from this side is less steep, these peaks are usually climbed from Lawn Lake because that approach is shorter (see Trails North of Horseshoe Park). From Mummy Mountain you can descend a south slope to the Cow Creek Trail and a left turn down Black Canyon toward the Cow Creek or the Lumpy Ridge Trailhead. A right turn at the Cow Creek Trail leads to the Lawn Lake Trail. If Lawn Lake itself is your goal, carefully descend the steep tundra slopes from the Mummy-Hagues saddle (avoid cliffs by traversing 0.5 mile west to descend less-precipitous slopes below Hagues) to reach the route between Lawn and Crystal Lakes.

You can climb from Hagues to Rowe Peak and Rowe Mountain by dropping a few hundred feet to below the tarn at the base of Rowe Glacier. From there climb steeply north to Rowe Peak. Losing and regaining altitude is easier than fighting the ragged spires on the knife ridge extending above the glacier between Hagues and Rowe Peaks.

There is a circle route back to Lost Lake via Icefield Pass, north of Rowe Mountain. Two more alpine lakes, Lake Louise and Lake Husted, add further joy to an easy meander across the tundra above Lost Lake.

Back at the North Fork patrol cabin, the North Boundary Trail heads south through fairly thick forest, crossing two streams as it winds steeply up a ridge. It descends to Fox Creek, then up and down again to West Creek, then up and down again to Cow Creek Trailhead, 6.0 miles from the North Fork.

As you can imagine, all this up and down becomes tiresome and dulls the mind to interesting details at trailside. Yet, because spectacular views are infrequent, sharp attention to detail is essential to make the North Boundary hike worth the effort. This trail is not the park’s best for hiking; horse riders have it pretty much to themselves. But for hikers with both endurance and perception, there are some nice spots. It definitely should be hiked from north to south, so you will be climbing on the relatively cool, somewhat less-steep northern slopes and descending the more open and warm southern slopes. Some details:

Fox Creek Falls is pleasant though not spectacular. It is reached by a trail extending from private land at the Trail’s End Cheley Camp, west of Glen Haven. It can also be reached from above by following Fox Creek down from where the North Boundary Trail crosses it, just outside the national park boundary.

Another trail junction comes up soon, this one with the Fox Creek Trail, on the left. Unless you have some personal reason for following Fox Creek to the east, there is little point in paying much attention to this little-used trail, which soon descends a very steep slope through switchbacks.

Past the Fox Creek Trail junction, the North Boundary Trail descends to West Creek. As you reach the valley floor but before you reach the creek, a spur trail cuts back sharply to the right, extending 0.5 mile upstream to West Creek Falls, inside the national park. You have more than 1.0 mile of steep walking ahead to the south end of the trail, and the hiker’s natural urge is to get on with it. Nevertheless, you may find it worthwhile to expend a little more effort on the pleasant side trip to these lovely falls.

The southern end of the Stormy Peaks Trail branches from the Lost Lake Trail immediately after a very steep section 7.6 miles from the Dunraven Glade Trailhead parking lot. Past the junction, the Stormy Peaks Trail is even steeper for almost 1.0 mile. The grade becomes less grinding near tree line, where you get a fine view of Rowe Peak and Rowe Mountain above Lost Meadows. Stormy Peaks Pass is another 1.0 mile up a less-steep section of trail. The effort required to make a short climb from the pass to the top of Stormy Peaks is amply rewarded by an excellent view.

From Stormy Peaks Pass you can skirt some rocky bumps for an easy walk west over the tundra to Sugarloaf Mountain. As you climb Sugarloaf, walk to the edge of the North Fork Valley for a spectacular view of the lakes below and the main peaks of the Mummy Range. From Sugarloaf you can descend via Skull Point and Icefield Pass to Lost Lake.

The Stormy Peaks Trail continues north below Stormy Peaks Pass. The path is faint in a few spots but easy and pleasant to follow downhill to the park boundary and out of the park through subalpine woods. The northern end of the trail is located at an entrance gate to the Pingree Park Campus of Colorado State University, about 7.5 miles from the Lost Lake Trail. The Stormy Peaks Trail affords good views of Pingree Park; its “campus” is more like a camp.

Stormy Peaks Pass is 9.7 miles from the Dunraven Glade Trailhead and just over half that distance from Pingree Park Trailhead. If your goal is the Stormy Peaks area, it is obviously easier to hike from the northern end of the trail.

To drive to Pingree Park from Fort Collins, take US 287 north to Colorado Highway 14. Drive 27.5 miles north and then west on CO 14. Two miles past Fort Collins Mountain Park, turn left onto Pingree Park Road (CR 63E) and drive 14 miles south to Pingree.

From Estes Park or Loveland, take US 34 to the Masonville Road, about 3 miles east of the Big Thompson Canyon. Drive through Masonville to the spot where the road ends in a T. Turn left (west) and drive northwest along Buckhorn Creek. Keep on until you reach a fork in the road more than 10 miles from Masonville. The right-hand fork goes to Stove Prairie; take the left-hand (lower) fork west to Pennock Pass and down to another T, about 25 miles from Masonville. Turn left and drive approximately 5 miles on a two-lane gravel road to a fork at Pingree Park. Take the left branch and continue 500 feet to the entrance gate. A sign marks the trailhead on the left side of the road.

Some maps show Signal Mountain Trail heading from the Stormy Peaks Trail to the park’s eastern boundary. This “trail” is hard to find and has disintegrated to the point where trying to follow it amounts to cross-country navigation. It can be traced in some sections (watch for old blazes on trees), but you will lose the path now and then and have to wander about, searching. When it disappears at last in an expanse of boulders accented with magnificent old limber pines, head for the ridgetop and try to retrieve the trail there. It was never located where maps indicate, on the side of the ridge, and it disappears completely above tree line on South Signal Mountain. Head straight up to the summit, or circle on its left (northern) flank to climb the slightly taller Signal Mountain just outside the park boundary.

The forest service trail from Signal Mountain down to the North Fork is well maintained. It is steep in some stretches and very steep in the rest. As it descends Bulwark Ridge, most of the trail passes through open limber or lodgepole pine forests, which normally are sunny and hot. The trail is used mainly by horses; hikers ascending it face a difficult grind. Signal Mountain Trail ends at the unpaved Dunraven Road west of Glen Haven at a gate marking the boundary between Roosevelt National Forest and private property. The road at this point is closed to public vehicles, but the Dunraven Glade Trailhead parking lot is located a few hundred yards to the east.