Pawnee Pass Trail

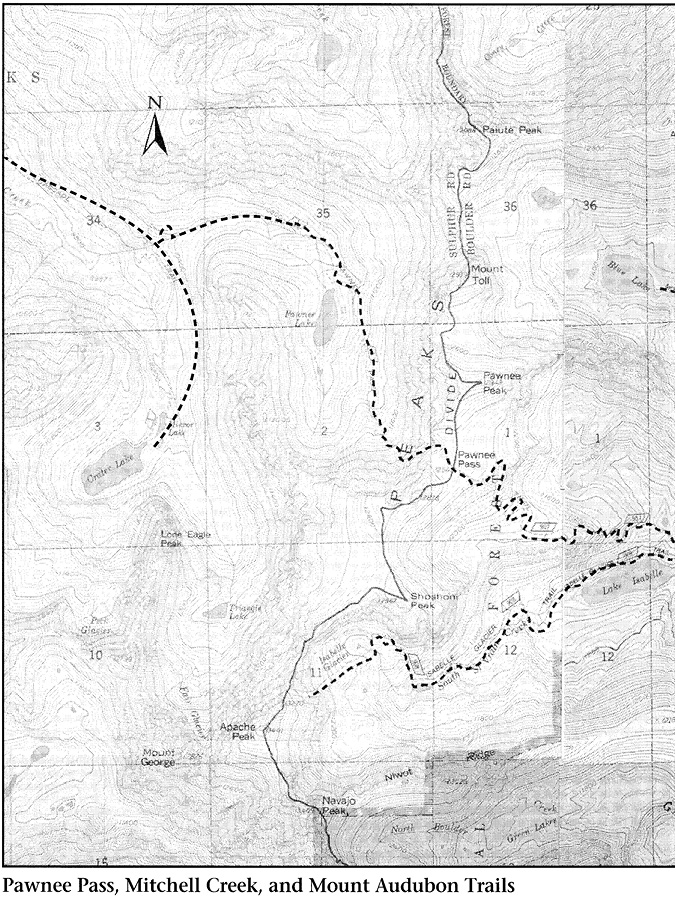

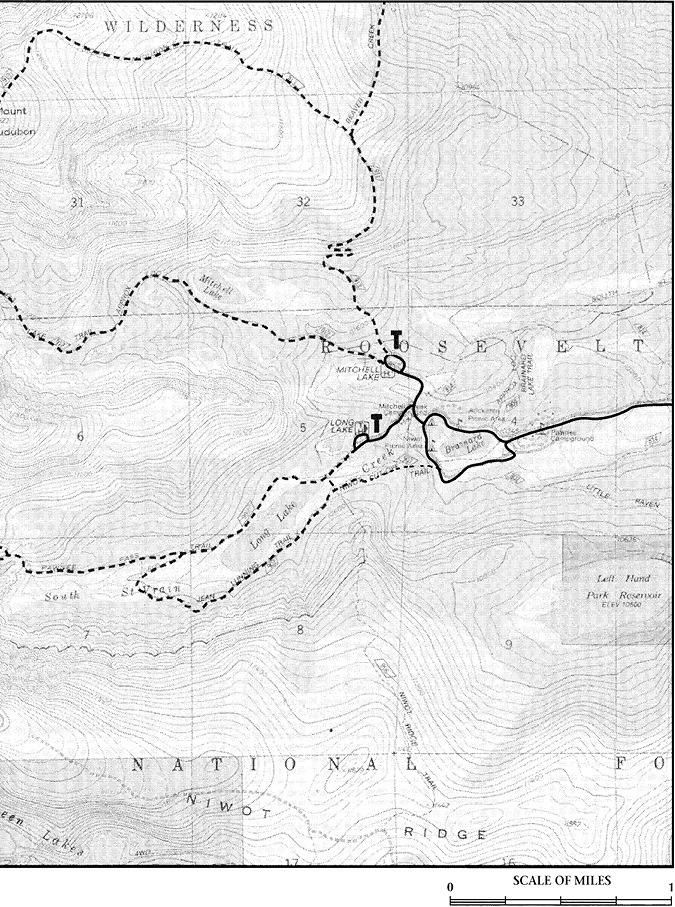

To reach trailheads in the Brainard Lake area, drive to the old mining town of Ward on CO 72. Just north of Ward, turn west at a sign that indicates the paved access road (CR 102) to Brainard Lake.

Early in the season (June), this road may be closed at a winter trailhead and vehicle fee station with a large parking area 3 miles from the highway. A 0.3-mile hike past this road closure takes you to Red Rock Lake, which has a good view of striking peaks to the west. After 1.7 miles more you reach Brainard Lake, a highly developed but very scenic campground area. A paved road circling the lake runs one-way to the right, crossing a bridge at the outlet. The road is the shortest route on foot to the Long Lake and Mitchell Lake Trailheads.

About the time the road to Brainard Lake and its trailheads is free of melting snow, the soggy subalpine soil may be dry enough to withstand the tramping of thousands of booted feet. (To prevent heavy damage to trailside vegetation and unsightly trampling, it is very important that everybody stay on the trail.) At a fork in the road on the west side of Brainard, 5.7 miles from CO 72, you can turn right to reach the most popular trailheads. About 200 yards up this road, you reach another fork. To the right are the Mitchell Lake and Beaver Creek Trailheads; to the left is the Long Lake Trailhead. The Pawnee Pass Trail, which connects Long Lake with Lake Isabelle, begins at the Long Lake Trailhead. The Niwot Cutoff Trailhead, an alternate starting point for Long Lake, is on the west side of Brainard Lake, beyond the turnoff to Mitchell and Long Lake Trailheads.

Camping is prohibited at Long, Isabelle, Mitchell, and Blue Lakes from May 1 to November 30 annually. No camping zone extends north to Mt. Audubon, west to Divide, south to Boulder Watershed, east to Brainard Lake.

Nature Walk to Lake Isabelle (Subalpine Zone)

The forest around the Pawnee Pass Trail is a good example of the subalpine zone of vegetation. Many hikers feel that a path in the subalpine forest provides the most pleasant walking found anywhere. The first stretch of the trail is particularly nice because it is flat.

The dominant growth along the way is Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir. Both are short-needled conifers whose needles grow individually from the twigs. Close examination reveals obvious differences between the two trees. The easiest test is to grab a branch. If it hurts, the tree is a spruce. Spruce needles are four-sided, stiff, and sharp. Fir needles are flat, soft, and blunt.

There are other differences as well. Engelmann spruce cones are brown, have parchmentlike scales, and hang down from the branches. You probably can see some of these small (less than 2 inches long) cones that have fallen to the ground. Fir cones, on the other hand, are dark purple to black and grow erect in the top of the tree. When fir cones are ready to spread their seeds, the scales do not open as do those of spruce and pine. Rather, the scales merely fall off, leaving the cores of the cones standing bare and upright.

The trunk of a subalpine fir is generally smooth and gray in color; after it grows to a foot or so in diameter, it becomes furrowed near the base. Blisters containing pitch are scattered over the smooth bark. The bark of an Engelmann spruce begins to flake off while the tree is still young. With age the trunk becomes red-brown and develops a scaly texture.

The plant life along this section of trail is relatively lush because the subalpine zone, extending from 9,000 feet to about 11,500 feet above sea level, gets more moisture than any other zone in Colorado. More than 22 inches of annual precipitation is normal here, almost double the amount expected down on the plains. Snow blown from the mountaintops accumulates in this zone, providing moisture vital to luxuriant growth.

Protected by the trees from wind and hot rays of the sun, snow remains here far into the summer. Melting slowly, snowbanks serve as reservoirs, constantly watering the trees during their short growing season. Thanks to the steady water supply, the forest grows taller and denser, providing more shade to protect more snow to nourish more growth, and so on in a circle of cooperation. There is a fascination in this system’s efficiency that only water-starved westerners can appreciate fully.

The forest shade is not the only reason for a supply of water. The forest floor is rich with years’ accumulation of rotting needles and other plant material. Their decay adds humus to the bits of minerals produced by disintegrating rock. The combination of organic and inorganic material creates fine-grained dark soil that retains water.

In drier areas in the mountains, where plant growth is much slower, little organic material is contributed to the soil. There the soil is light in color and consists of larger particles. It has no humus to hold it together, and water percolates quickly away. In the case of water so essential to plant survival, it is surely true that “them that has, gets.”

Forming a continuous ground cover over much of the damp forest floor is grouseberry, or broom huckleberry. This shrub has small leaves that turn bright red in fall and tiny urn-shaped flowers that mature to small red berries. The berries are fairly tasty, although less so than some other members of the blueberry family. They are a favorite food of many species of wildlife, including the blue grouse.

Flowers common in shady areas along the trail include Jacob’s ladder, with sky-blue blossoms and ladderlike leaves whose leaflets grow opposite each other on a central stalk, and arnicas, which are totally yellow composites. Growing in sunny areas is the brilliant, dark pink fireweed, named not for its color but for a tendency to invade areas that have been opened up by forest fires or other disturbances, such as avalanches.

Less conspicuous plants are the lichens, the gray-green splotches that you see on rocks next to the path. Lichens represent a relationship in nature called mutualism or symbiosis—a partnership between algae and fungi. The algae, which contain chlorophyll, produce food for the fungi. The fungi, in turn, absorb and store water for the algae. They cooperate so well that lichens thrive where no other plants can survive. On bare rocks in hot deserts and in the frigid Arctic, lichens of many varieties display the advantages of partners working together for their common good.

These crusty plants actually contribute to the disintegration of rocks and the building of soil. Lichens adhere very strongly to the rock surface. When they are wet, their colors (which can be far more varied than they are here) are brilliant, but when they dry out and their colors fade, they shrink or curl up. This small movement tends to loosen the bits of rock to which the lichens are attached, causing some particles to fall away as sand.

Lichens further break down rock by secreting small amounts of organic acids, which, mixed with water, gradually dissolve the bonding material that holds the rock together. Such acids are comparatively weak, of course, and the wearing away of a rock is not noticeable in several human generations.

Soon after leaving the trailhead you see the woods to your left opening up along the banks of South St. Vrain Creek. The name of St. Vrain is scattered all over the Indian Peaks and Wild Basin areas, and it has a colorful history. Brothers Ceran and Marcellin St. Vrain were nineteenth-century traders who swapped goods with Native Americans in exchange for furs and hides.

Rydbergia and Alpine Clover

The profit was vanishing from the beaver trade in 1837 when the St. Vrain brothers built Fort St. Vrain on the South Platte River, yet they and their partners, the Bents, managed to do well. Experienced traders, they exploited the expertise of mountain men like Kit Carson, who knew the trapping business well but had been reduced to picking the bones of a dying trade. Such men still operated efficiently in the Colorado Rockies, which had not yet been trapped out like the mountains farther north in Wyoming.

Easily accessible to Native Americans, the site of the St. Vrain trading post was well chosen. The Bents and St. Vrains were the fairest traders in a generally unscrupulous business. Soon their honorable dealings had gained them the entire business of the Southern Cheyenne and most of the Arapaho. By their unusual honesty, they were able to maintain a nearly permanent truce among their constantly warring customers in the vicinity of the post.

But mainly the St. Vrains were just smart businessmen: They diversified. Their economic base consisted not only of the very shaky beaver trade but also of trade with Santa Fe and a general retail business. Eventually, after gold was discovered, there was a St. Vrain trading post in the new town of Denver.

South St. Vrain Creek, which you see from the Pawnee Pass Trail, flows into a creek that in turn flows into the South Platte just upstream from the St. Vrain brothers’ 1837 trading post. The peaks that surround you were named for the St. Vrains’ Native American customers.

Long Lake is 0.25 mile from the trailhead. Here, just inside the wilderness boundary, the trail divides. The left-hand branch crosses the bridge and divides again: A turn to the left on the Niwot Cutoff Trail takes you back down to Brainard Lake at the Niwot Mountain Picnic Area. A turn to the right takes you on a loop trail (Jean Lunning Trail) that circles Long Lake, providing fine views of the jagged peaks rising overhead, and meets the Pawnee Pass Trail on the west side of the lake. A loop hike around Long Lake is 4.1 miles.

From the east end of the loop trail, the Niwot Ridge Trail heads uphill to the tundra slopes on broad Niwot Ridge. If you elect to go all the way to the ridgetop, you will arrive at the boundary of the Boulder watershed. The city of Boulder is very diligent about keeping people out of this area, however, and you would be better off acceding to its wishes, or hefty fines may result.

It is even more important to avoid disrupting the natural history

experiments being conducted on Niwot Ridge by the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research. Years of data collecting can be ruined by one careless step or handling of markers. It also is wise to refrain from poking around inside the mountain research station building that IAAR maintains on the ridge.

Back on the Pawnee Pass Trail, at the east end of Long Lake, follow the right-hand fork along a level grade roughly parallel to the lake’s northern shore. Long Lake is long indeed, extending about a third of the way to Isabelle Lake. In several places the trail is built up above bogs.

These are excellent spots for observing the results of plant succession. Pools of water are formed by glacial action or by the blocking of drainages by beavers or human beings. Tiny algal plants are the first vegetation to invade these pools. Some algae float; others find a home on wet rocks at the water’s edge. Among the rocks, moisture-loving mosses and liverworts (some species resemble lobed livers; wort is Old English for “plant”) also establish plant communities. These pioneer plants help to create soil on the margin of the pond, as do lichens on the surface of a rock. Although it is a small beginning, it is important.

The seeds of various plants land on the mud at the shoreline. Others end up in shallow water; still others come to rest in deeper water. Then they germinate and grow according to specific adaptations to specific pond environments. Some species grow submerged entirely in deep water. Others are rooted in mud in shallower water, and their leaves float on the surface. There are no floating-leaf varieties along this path, but they are obvious in Red Rock Lake, which you passed along the road to Brainard Lake.

The most common and varied seed-producing water plants are the sedges, rushes, and water grasses growing in shallow water along the pond’s margin. Various willows and other deciduous shrubs spring up around the soggy shore. Farther from the water are dry land grasses and then the coniferous forest. You can easily see most of these concentric zones of vegetation in the marshes next to Long Lake.

Year after year the plants grow and die, slowly depositing layers of organic material. The process of decay builds soil composed mostly of humus. Humus and other material carried by wind and running water gradually fill in the pond, lowering the water level and drying out the margins.

Plants that require drier habitat invade the filled-in edges of the pond. The ones that need water over their roots begin to grow in a ring closer to the pond’s center as the entire body of water becomes shallower. Plants requiring deep water, which no longer exists, can no longer survive in the pond.

The plant life continues to change as the pool gradually shrinks and is succeeded by marsh, which is succeeded by meadow, which is succeeded by forest. In the subalpine zone, plant succession stops with Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir, the so-called climax plants. Of course fire can destroy a spruce-fir forest, including its humus soil. In such a situation, lodgepole pine and quaking aspen tend to succeed. Centuries later, spruce and fir again will take over and will grow until beavers or people build another pond or until fire sweeps the area once more. Change is the most universal condition in nature.

The flowers that are obvious along this section of the Pawnee Pass Trail are typical of wet subalpine areas. White marsh marigold is the first to appear after snow has melted in the sunny bogs. In midsummer, rose crown, with its fleshy leaves, is very conspicuous. The deep-pink spikes of elephant head blossoms are beautiful from a distance and fascinating close up. Each blossom looks like the flower’s namesake. Fireweed grows in drier areas, a brightly garbed herald of the encroaching forest.

Past the marshes, the trail once more enters pure subalpine climax forest. Frequently on grand old trees you will see burls, which are flattened hemispheres bulging from the trunks. A burl generally originates at the site of an adventitious bud—a bud that grows at an abnormal place, such as the side of a tree trunk, where the plant is not putting on any length. Such buds have no vascular system to carry water or minerals to nourish growth. The buds are eventually covered by trunk tissues—burls—having very dense, contorted, wild, and disorderly grain structure. Such analogous growths on humans are termed cancer.

Hopefully the medical analogy will not spoil burls for you. Burls are benign in that they do no harm to the tree. When trees are cut for lumber, burls themselves can be valuable. Their natural shape suggests their transformation into wooden bowls, which are much desired for their beautiful mottled grain. The grain makes burls appropriate as veneer—thin slices of wood used to overlay less-attractive wood, particularly on furniture.

Furthermore, burls are beautiful growing on the tree. The way their round shapes contrast with the rough texture of the bark inspires some very fine photos. Often a tripod and a slow shutter speed are necessary for getting maximum depth of field in close-ups in less-than-bright forest light.

The philosopher of Ecclesiastes stated that God “has made everything beautiful in its time.” That broad generalization is proven true in the forest, where even a cancerous deformity becomes a thing of beauty. Conservationist John Muir observed that all things in nature, “however mysterious and lawless at first sight they may seem, are only harmonious notes in the song of creation, varied expressions of God’s love.”

About 0.75 mile from the trailhead, and in other places along the trail, you may notice a familiar-looking plant, a clover. Its leaves and flowers are easily recognized. Although there are native clovers in the Rockies, the clovers growing alongside this section of trail are aliens. They were introduced here by horses that ate hay brought in from the plains. The hay contained clover seeds, which passed through the horses’ digestive systems and were deposited along the trail, fertilized and ready to grow.

No horses have been permitted on the Pawnee Pass Trail since 1965. Therefore it seems that these alien plants have been maintaining their population for a significant length of time without the help of any new seeds. So far as is known, the alien clover does not have a serious impact on the local ecosystems, but mankind’s accidental introduction of alien organisms into natural areas has often been catastrophic. Water hyacinth clogs waterways in the South; alien insects have caused the destruction of chestnuts, elms, and dogwoods in the East. Many more horror stories emphasize that we must be extremely careful not to introduce chaos into a delicately balanced system.

Past the western end of Long Lake, the trail divides. The left-hand fork is the loop trail around the lake. The right-hand fork begins, gradually at first, to climb toward Lake Isabelle and Pawnee Pass.

Soon the way levels out and you notice more marshland on the left. This is a classic example of plant succession, showing almost all the stages. There still remains a central pool, but it has been almost completely taken over by marsh.

This pool was considerably larger following the retreat of the last glacier 8,000 years ago. The moving masses of ice carried rocky rubble to this point and dropped it when the ice melted. The ridge or moraine thus formed was piled up next to an older landform, and the depression between them filled with water.

Plant succession began very slowly at first because there was little time for plant development in the short growing season and little or no soil for plant habitat. But succession picks up momentum, progressing at ever-increasing speed as more and more plants throw themselves into the task of creating soil. In terms of land formation, succession at the marsh is racing along at this time. Some change might be observable within one human generation.

As you walk past the marsh, high jagged peaks that have been hidden from sight for the last mile come into view to the west, supplying new drama and awe-inspiring beauty. The sculpting power of snowflakes becomes immediately impressive.

About 27,000 years ago the climate in this area cooled to the extent that snow at the top of the mountains failed to melt in summer. Snow began to accumulate in the low places between the peaks, where wind from the west dumped extra amounts and where it was protected to some extent from the sun. As more and more snow piled up, the bottom layers were crushed by the weight of the upper layers. The compacting pressure squeezed out all the air spaces, creating a solid mass of ice under perhaps 100 feet of snow. Eventually the weight of snow and ice became so great that it forced the ice at the bottom to flow downhill, like molten plastic.

As a glacier flows it carves the surrounding mountains in several ways. At the headwall, where the glacier first forms, summer meltwater seeps into cracks in the rocks, only to refreeze at night or when winter returns. Water expands as it freezes, forcing the cracks to widen and eventually wedging off chunks of rock. The chunks are frozen into the glacier’s mass and carried away in its flow.

Through the centuries this quarrying action forms steep cliffs, many of them shaped like bowls. The cliff-sided basin at a glacier’s headwall is called a cirque. A part of a cirque is visible on the left side of Shoshoni Peak, the main double-pointed summit that dominates the view from the trail. The cirque’s distinctive shape is not obvious from here though. You will be able to pick out two classic cirques from Lake Isabelle.

As a glacier moves downhill, it quarries the rock beneath it too. In this way it widens the floor and steepens the walls of the valley through which it flows, giving the valley a typical U shape. Simultaneously, the ice carves away at softer areas of bedrock, forming giant ledges or stairs on the valley floor. The tons of rock carried by the ice act as the rasps on a file, enabling the glacier to scour basins on the ledges. When the ice finally melts, the basins become glacial lakes, or tarns. Lake Isabelle is a tarn sitting on such a shelf.

To reach Lake Isabelle, you must leave the nearly level grade where you have been walking and turn onto switchbacks that climb through the forest. It may seem easier to bypass the switchbacks and head straight uphill. This course might be quicker, but presumably you are having a good time and are in no big hurry to finish your walk.

More importantly, shortcutting switchbacks does great harm. It causes unnecessary wear to the vegetation and soil, setting up a perfect path for destructive erosion. In one area along these switchbacks, the USFS is trying to restore land severely damaged by shortcutting hikers.

Many folks are surprised to learn that trails are designed not so much to be easy on hikers as to be easy on the terrain. It is a happy arrangement that trails that protect the land also follow the easiest way to walk.

At the top of the switchbacks, you traverse a steep meadow with a brook tumbling down it. The meadow is lush with colorful wildflowers. Particularly eye-catching is the dark pink Parry’s primrose, which grows right next to the water or on a cushion of soil atop rocks in the middle of the stream.

Ford the stream and bear left. Lake Isabelle is situated on the other side of a low ridge facing you to the west. Very likely you will have to cross a short patch of snow to get there.

Lake Isabelle has been enlarged by a small dam and converted to a reservoir. When the water is drawn down for agricultural uses (as happens most years in late summer and fall), the lake becomes an ugly mudflat, commemorating the corruption of what could be one of the loveliest tarns in Colorado. In any case, the mountains are always fine. As you face the lake, the long ridge rising behind you on the left is Niwot Ridge. The conical peak is Navajo; the doublehumped peak to the right of Navajo is Apache. Shoshoni, on the far right, was pointed out earlier. There is a cirque with a permanent snowfield between Navajo and Apache and a second one between Apache and Shoshoni. In this second cirque lies Isabelle Glacier, the source of South St. Vrain Creek.

Isabelle Glacier is the most easily accessible glacier described in this book. Like all the other glaciers in the area, it was born just 3,000 years ago during a slight cooling following a period when the climate was warmer than today. It is not a very active glacier and is barely holding its own against the sun.

To reach Isabelle Glacier follow a path along Lake Isabelle’s northern shore. At the western end of the lake, follow South St. Vrain Creek upstream from the inlet until krummholz forces you to the right. Ascend over rocks and through small gullies, surmounting a series of glacial ledges toward the eastern end of the glacier, roughly 2.0 miles from the eastern end of Lake Isabelle.

An irresistible urge to climb up the glacier and slide down comes over some hikers at this point. That is unfortunate, because the rocks at the bottom of the glacier have no trouble resisting sliders who splat down against them at high speed. The glacier is especially steep on the Apache Peak side. There have been serious injuries and at least two fatalities here. Be careful.

No marked path exists up Apache Peak, but the least-difficult route is obvious from the glacial shelves above Lake Isabelle. Bearing southwest of the South St. Vrain Creek drainage, pick your way over the boulders and head for the saddle on top of Apache between the left (lower) and right summits. Note a very steep slope covered with large loose rocks, called talus, to the right of the permanent snowfield between Navajo and Apache. This talus slope is the least-difficult way past the cliffs that guard Apache’s east face. Please do not kick the loose rocks down on the heads of the climbers below you.

The most popular route for climbing Navajo Peak begins in the same way as the route up Apache, on the glacial shelves above Lake Isabelle. On the level, bouldery floor of the cirque below Navajo’s permanent snowfield, turn left to head up “airplane gully.” Of the two obvious ravines on Navajo’s flank, it’s the one on the left, marked by the wreckage of a late 1940s plane crash scattered throughout its entire length and at its base.

Airplane gully is full of small loose rocks, called scree. This stuff is extremely difficult to walk on (wade through) because it keeps slipping underfoot and carrying you back downhill. Even worse, it presents the real threat of accidentally bombarding climbers below with dangerous rocks.

A group’s best method of overcoming this gully is to climb very close together so as to catch bounding rocks before they can pick up momentum. Stay alert to what is happening above—no stolid concentration on your feet here. You’d miss a lot of scenery that way, anyhow. Short gaiters are nice for keeping rocks out of your boots.

At the top of the gully, turn right onto a tundra saddle. Continue west straight up the southeastern shoulder of Navajo toward the cliff-bound summit tower. At the base of the southeastern section of the tower, look for a vertical gully, or chimney, that provides an interesting climb to the summit.

Back in the meadow at the northeast end of Lake Isabelle, the trail to Pawnee Pass turns to the right. It climbs for a short way and then veers left (west), following a contour above the lake. About three-quarters of the way along the northern shore, it runs through a series of switchbacks that climb to a bench situated about 1,000 feet above Lake Isabelle. There is a good overlook of the lake and excellent views of Navajo Peak as the trail winds up this bench toward Pawnee Pass. At a final series of switchbacks, you leave the tundra of the bench and climb through boulders to more tundra at the pass.

West of Pawnee Pass the trail goes downhill to Pawnee Lake. The slope is very steep and rocky, and the path is the most masterful example of sinuous, switchbacking trail construction in the entire area covered by this book. (For a description of Pawnee Pass Trail beyond Pawnee Lake, see Cascade Trail to Pawnee Pass in the West of the Divide chapter). The spire-decked western cliffs of Pawnee Peak are certainly worth a photo themselves, and they make a dramatic frame for a picture of Pawnee Lake. Photos of the spires need a hiker in the distant foreground to provide size perspective.

Turning right from the trail at Pawnee Pass, you can follow the Continental Divide over easy terrain, given the nearly 13,000-foot altitude, to the top of Pawnee Peak. Continuing north along the divide from Pawnee Peak is considered by many to be the easiest way up Mount Toll (see Mitchell Creek Trail).

To climb Shoshoni Peak strike left (south) from the Pawnee Pass Trail just before the final set of switchbacks east of the pass. Traverse the steep, rocky slope to the saddle between Shoshoni and an unnamed rise south of Pawnee Pass. Once on the saddle you face a gentle tundra walk almost to the summit. The last 10 or 20 feet up the summit knob require a rock climb that might make acrophobic folks nervous.