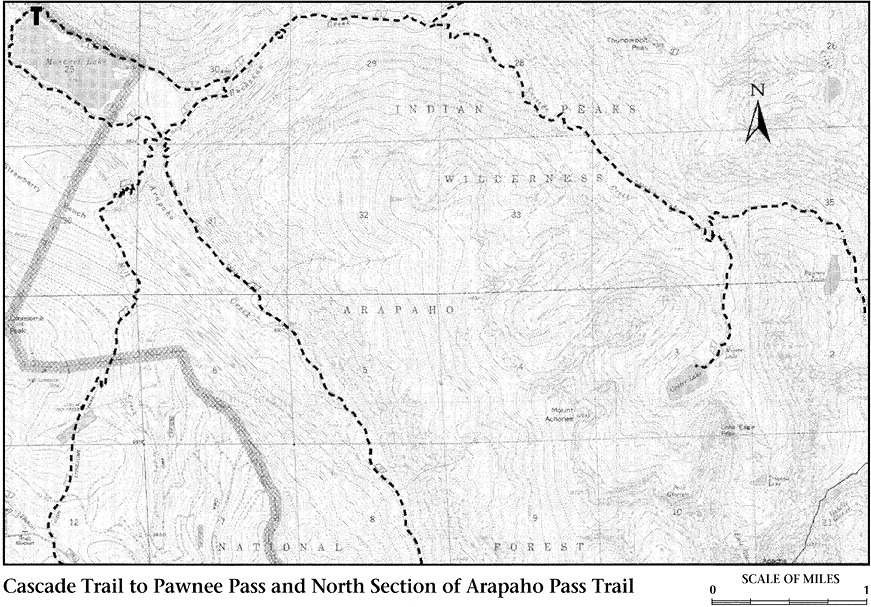

Cascade Trail to Pawnee Pass

The trail along Cascade Creek is the most heavily used trail on the west side of Indian Peaks, despite relatively long distances to the most popular destinations. Although the dramatic scenery in Cascade Creek’s drainage can be equaled on other trails, it cannot be surpassed. If you have a choice, make every effort to enjoy this trail at times other than obviously crowded holidays and weekends.

The Cascade Trail to Pawnee Pass branches right from the Buchanan Pass Trail at the trail junction 4.0 miles from Monarch Lake, just past Shelter Rock (see page 253). A short level walk takes you to Buchanan Creek, which is spanned by a substantial bridge. From there a short and rather steep stretch moderated by one switchback leads to the edge of a canyon cut by Cascade Creek. The grade moderates from the canyon edge as you continue up the valley through lodgepole pines.

About 1.0 mile from Shelter Rock, the trail bends to the right and crosses the creek on a bridge. Notice the sign at this crossing that campfires and horses are prohibited beyond this point. The open marshy area here is in a middle stage of plant succession from beaver pond to forest. Located upstream from the old beaver workings is your first clear example of how Cascade Creek got its name. Falls like this, too numerous to be named individually, make the trail a hiking destination in itself rather than merely a route to the lakes at the base of the peaks.

Twisting through many tight switchbacks, the trail climbs along the cascades onto the next highest glacier-cut shelf. The views of rushing water will slow you down even more than the steepness of the climb. Various spur paths branch off to viewpoints of the cascades. If you are in a rush, keep to the right on the main trail. Near the level of the next shelf, the trail bends to the left to recross the creek over water-smoothed rock above particularly fine falls.

A bit more climbing takes you to another broad, level area where Cascade Creek meanders lazily through old beaver ponds, seemingly resting before its spectacular rush down the falls. Amid the rock-covered slopes overhead on the left, groves of quaking aspens have pioneered a place to live among the boulders. Leaving the creek on the valley floor, the trail traverses uphill along a sunny south-facing slope. Peaks in the vicinity of Mount George, to the east, draw your attention as you climb.

The trail reenters deep spruce and fir forests before crossing Pawnee Creek. A short winding way uphill is a trail junction, about 7.0 miles from Monarch Lake. The right-hand fork, Crater Lake Trail, continues up Cascade Creek to Mirror and Crater Lakes.

The Pawnee Pass Trail branches left and recrosses Pawnee Creek. Switchbacks just past the crossing climb through quaking aspens and narrow spires of Engelmann spruce. These trees are good frames for effective photos of Lone Eagle Peak flanked by Peck and Fair Glaciers (see Crater Lake Trail, page 259).

Variations on this spectacular view continue as the trail climbs east, parallel to Pawnee Creek. Lone Eagle and its glaciers are last seen from an open avalanche slope covered with large boulders. The trail continues ascending through spruce-fir forest into the cirque containing Pawnee Lake. The lake is a little more than 1.0 mile from the junction of the Crater Lake Trail.

Pawnee Lake is extremely grand. Spires on the slopes of Pawnee Peak, east of the lake, are picturesquely jagged. The glacier-quarried peaks on the north and west, although unnamed, are nearly as spectacular.

Beyond Pawnee Lake the 2.5-mile ascent to Pawnee Pass is very steep. The path, however, is a remarkable example of superb trail construction. In tight switchbacks it snakes up terrain that must approach the maximum limit of steepness and ruggedness for trail building. If you climb it, be sure to use your rest stops to photograph over the switchbacks to Pawnee Lake, using rock spires on Pawnee Peak for a frame. East of Pawnee Pass are various trail systems in the vicinity of Brainard Lake (see Pawnee Pass Trail in the East of the Divide chapter).

The Crater Lake Trail branches from the Pawnee Pass Trail about 7.0 miles from Monarch Lake. Camping in this area is extremely popular and limited to designated sites, so get your permit requests in early. Campfires are prohibited. As you ascend the sometimes wet, sometimes rocky path to Crater Lake, the impossibly pointed spire of Lone Eagle Peak comes into view above the trees, echoing their sky-etching quality. The classic view of Lone Eagle is from Mirror Lake, a shallow, rock-rimmed tarn a few hundred yards past the third crossing of Cascade Creek. Fair Glacier is on the left of Lone Eagle, Peck Glacier on the right.

Less than 0.5 mile past Mirror is Crater Lake, where the view of Lone Eagle is more believable. But the setting of subalpine forest, large deep lake, spires and cliffs of Mount Achonee on the right, incredibly jagged ridge on the left, and the sheer face of Lone Eagle rising straight up to a point creates a scene of extravagant grandeur. The one-time occupants of a tumbledown old cabin perched atop glacially smoothed bedrock at the lake’s western end had quite a view when they arose each morning.

If you can stop staring at Lone Eagle, there are several interesting hikes to take from Crater Lake. To reach Peck Glacier, circle Crater Lake to the right (west) and climb along the base of Lone Eagle’s western flank. It is a steep 1.0 mile from the lake’s northern shore to the glacier.

The spire of Lone Eagle Peak that is seen from Crater Lake is not a true summit. Lone Eagle really is a jagged ridge extending north from Mount George. The highest point on the ridge (12,799 feet; the spire above the lake reaches 11,950 feet) can be climbed from the east. Cross the outlet stream of Crater Lake to the slopes of loose rock below Lone Eagle ridge. Make your way up this rock, following the base of the ridge.

Eventually you will come upon snatches of faint trail and cairns that lead south and up rock slabs at a relatively moderate grade for more than 0.5 mile. Watch carefully for cairns, and do not try to cut uphill too soon or cliffs will block your way. After you are well south of the high point on the ridge, the route cuts back to the north and begins to climb ramps to the ridgeline at a point south of the summit. From here you must descend a few feet over slabs on the western side of the ridge, circling a small spire. This spot is exposed to a long drop and, though not difficult, can be unnerving.

Climbing back over the ridgeline toward the summit spire, you ultimately must head to the right (east) side of the ridge and then ascend to the very top from the northeast. The summit is not so sharp that it hurts to sit on it, but there is room for only a few climbers at a time. The entire climb is exciting, dramatic, and less difficult than it appears from below. On the other hand, Lone Eagle has claimed its share of lives, so be very careful. Turn back when rain threatens to make rocks slick or if you anticipate a storm.

Triangle Lake is an aptly named tarn lying in the valley below the route to Lone Eagle. To reach Triangle, cross the outlet of Crater Lake and ascend the valley through forest and meadow. Clamber up a short, steep barrier of boulders to the lake, about 1.0 mile from Crater. Triangle’s water is milky, which indicates that powdered rock is being carried into the lake in meltwater from Fair Glacier. Evidently enough ice is still flowing in the glacier to keep it actively grinding rocks.