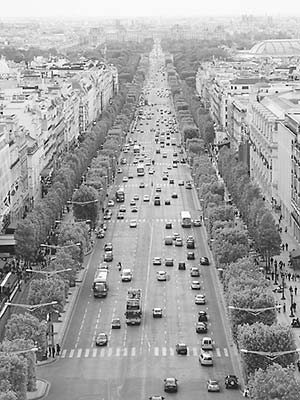

From the Arc de Triomphe to Place de la Concorde

Rue de Tilsitt and Qatar Embassy

Rue de Tilsitt and Qatar Embassy

Glitz: Peugeot, Mercedes-Benz, Lido

Glitz: Peugeot, Mercedes-Benz, Lido

Café Culture: Fouquet’s and Ladurée

Café Culture: Fouquet’s and Ladurée

French Shopping: Arcades Mall, Sephora, Guerlain

French Shopping: Arcades Mall, Sephora, Guerlain

International Shopping and Citroën

International Shopping and Citroën

Don’t leave Paris without a stroll along Avenue des Champs-Elysées (shahnz ay-lee-zay). This is Paris at its most Parisian: monumental sidewalks, stylish shops, elegant cafés, glimmering showrooms, and proud Parisians on parade. The whole world seems to gather here to strut along the boulevard. It’s a great walk by day, and even better at night, allowing you to tap into the city’s increasingly global scene.

(See “Champs-Elysées Walk” map, here.)

Length of This Walk: This two-mile walk takes three hours, including a one-hour visit to the Arc de Triomphe. Métro stops are located every few blocks along the Champs-Elysées. With less time, end the walk at Rond-Point (Mo: FDR).

Getting There: To reach the Arc de Triomphe at Place Charles de Gaulle, take the Métro to Charles de Gaulle-Etoile. Then follow the Sortie #1, Champs-Elysées/Arc de Triomphe signs. From Rue Cler and the Montparnasse area, bus #92 works best.

Arc de Triomphe: Free and always viewable; steps to rooftop—€9.50, free for those under age 18, free on first Sun of month Oct-March, covered by Museum Pass; daily 10:00-23:00, Oct-March until 22:30, last entry 45 minutes before closing. Bypass the slooow ticket line with your Museum Pass (though if you have kids, you’ll need to line up to get their free tickets). Expect another line (that you can’t skip) at the entrance to the stairway up the arch. The elevator is only for people with disabilities (and runs only to the museum level, not to the top, which requires a 40-step climb). Lines disappear after 17:00—come for sunset.

Grand Palais: Major exhibitions usually €11-15, not covered by Museum Pass, generally open daily 10:00-20:00, Wed until 22:00, some parts of building closed Mon, other parts closed Tue, closed between exhibitions.

Petit Palais: Free, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, Fri until 21:00 for special exhibits (fee), closed Mon.

Services: A small WC is inside the Arc de Triomphe, near the top, but it’s often crowded. WCs are also at the Arcades des Champs-Elysées, Petit Palais (no lines), and Tuileries Garden (at the end of the walk). Most restaurants (McDonald’s, etc.) and bigger stores along the route have WCs as well.

Starring: Grand boulevards, grander shops, and grandiose monuments.

(See “Champs-Elysées Walk” map, here.)

Arc de Triomphe

Arc de Triomphe• Start with the Arc de Triomphe, at the top of the Champs-Elysées. View the Arc from the right side of the boulevard (“right” as you face the Arc).

Construction of the 165-foot-high arch began in 1809 to honor Napoleon’s soldiers, who, despite being vastly outnumbered by the Austrians, scored a remarkable victory at the Battle of Austerlitz. Patterned after the ceremonial arches of ancient Roman conquerors (but more than twice the size), it celebrates Napoleon as emperor of a “New Rome.” On the arch’s massive left pillar, a relief sculpture shows a toga-clad Napoleon posing confidently, while an awestruck Paris—crowned by her city walls—kneels at his imperial feet. Napoleon died before the Arc’s completion, but it was finished in time for his 1840 funeral procession to pass underneath, carrying his remains (19 years dead) from exile in St. Helena to Paris.

On the right pillar is the Arc’s most famous relief, La Marseillaise (Le Départ des Volontaires de 1792, by François Rude). Lady Liberty—looking like an ugly reincarnation of Joan of Arc—screams, “Freedom is this way!” and points the direction with a sword. The soldiers beneath her are tired, naked, and stumbling, but she rallies them to carry on the fight against oppression.

• Now approach the Arc. Take the underground pedestrian walkway—don’t try to cross the roundabout in all the traffic, as there are no crosswalks. It’s worthwhile to get to the base of the arch even if you don’t climb it. There’s no cost to wander around. After crossing through the tunnel, take the first left up a few steps, where you’ll find the ticket booth (with a Museum Pass, you can skip the booth and its lines altogether, unless you need free tickets for kids). Now walk up to the arch.

Today, the Arc de Triomphe is dedicated to the glory of all French armies. Walk to its center and stand directly beneath it on the faded eagle. You’re surrounded by the lists of French victories since the Revolution—19th century on the arch’s taller columns, 20th century in the pavement. On the shorter columns you’ll see lists of generals (with a line under the names of those who died in battle). Find the nearby Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (from World War I). Every day at 18:30 since just after World War I, the flame has been rekindled and new flowers set in place.

Like its Roman ancestors, this arch has served as a parade gateway for triumphal armies (French or foe) and important ceremonies. From 1940 to 1944, a large swastika flew from here as Nazis goose-stepped down the Champs-Elysées. In August 1944 General Charles de Gaulle led Allied troops under this arch as they celebrated liberation. Today, national parades start and end here with one minute of silence.

Ascend the Arc via the 284 steps inside the north pillar. Catch your breath two-thirds of the way up in the small exhibition area (WC also on this mezzanine level). It hosts ho-hum exhibits about the arch (though the down-camera is cool) and its founder, Napoleon. And, of course, there’s a gift shop a few steps higher.

From the top you have an eye-popping view of tout Paris. You’re gazing at the home of 11 million people, all crammed into an area the size of an average city in the US (the city center has about 2.3 million residents and covers 40 square miles). Paris has the highest density of any city in Europe, about 20 times greater than that of New York City.

Looking East: Look down the Champs-Elysées to the Tuileries Garden and the Louvre. Scan the cityscape of downtown Paris. That lonely hill to the left is Montmartre, topped by the dome of Sacré-Cœur; until 1860, this hill town was a separate city. Panning right, find the bulky Opéra Garnier’s pitched roof rising above other buildings, the blue top of the modern Pompidou Center, and the Louvre and Tuileries Garden capping the east end of the Champs-Elysées. Let your eyes cross the river to see the distant twin towers of Notre-Dame, the dome of the Panthéon breaking the horizon, a block of small skyscrapers on a hill (the Quartier d’Italie), and the golden dome of Les Invalides. Near Les Invalides, find the lonely-looking Montparnasse Tower, standing like the box the Eiffel Tower came in; in the early 1970s, it served as a wake-up call to city planners that they needed to preserve building height restrictions and strengthen urban design standards. Aside from the Montparnasse Tower, notice the symmetry. Each corner building surrounding the arch is part of an elegant grand scheme. The beauty of Paris—basically a flat basin with a river running through it—is man-made. There’s a harmonious relationship between the width of its grand boulevards and the standard height and design of the buildings.

Looking West: Cross the arch and look to the west. In the distance, the huge, white, rectangular Grande Arche de la Défense, standing amid skyscrapers, is the final piece of a grand city axis—from the Louvre, up the Champs-Elysées to the Arc de Triomphe, and continuing on to a forest of skyscrapers at La Défense, three miles away. Former French president François Mitterrand had the Grande Arche built as a centerpiece of this mini-Manhattan. Notice the contrast between the skyscrapers of La Défense and the more uniform heights of the buildings closer to the Arc de Triomphe. Below you, the wide boulevard lined with grass and trees angling to your left is Avenue Foch (named after the WWI hero), which ends at the huge Bois de Boulogne park. Avenue Foch is the best address to have in Paris. Nicknamed the “Avenue of Millionaires,” it was home to the Shah of Iran and Aristotle Onassis. Today many fabulously rich Arabs call it home. And though Parisians pride themselves on being discreet, some not-so-discreet Homes-of-the-Stars-type tours are offered here. The skyscraper to the right between you and La Défense is the Hôtel Hyatt Regency, which delivers Paris’ best view bar scene (described on here). To the left of La Défense (in the Bois de Boulogne) are the glassy “sails” of the Louis Vuitton Foundation. This wavy building, another of Frank Gehry’s wild creations, offers contemporary art exhibits.

The Etoile: Gaze down at what appears to be a chaotic traffic mess. The 12 boulevards that radiate from the Arc de Triomphe (forming an étoile, star) were part of Baron Haussmann’s master plan for Paris: the creation of a series of major boulevards intersecting at diagonals, with monuments (such as the Arc de Triomphe) as centerpieces of those intersections (see sidebar on here). Haussmann’s plan did not anticipate the automobile—obvious when you watch the traffic scene below. But see how smoothly it functions. Cars entering the circle have the right of way (the only roundabout in France with this rule); those in the circle must yield. Still, there are plenty of accidents, many caused by tourists oblivious to the rules. Tired of disputes, insurance companies split the fault and damages of any Arc de Triomphe accident 50/50. The trick is to make a parabola—get to the center ASAP, and then begin working your way out two avenues before you want to exit.

• We’ll start our stroll down the Champs-Elysées at the Charles de Gaulle-Etoile Métro stop, on the north (sunnier) side of the street where the tunnel deposits you. Look straight down the Champs-Elysées to the Tuileries Garden at the far end.

Champs-Elysées

Champs-ElyséesYou’re at the top of one of the world’s grandest and most celebrated streets, home to big business, celebrity cafés, glitzy nightclubs, high-fashion shopping, and international people-watching. People gather here to celebrate Bastille Day (July 14), World Cup triumphs, the finale of the Tour de France (see sidebar later in the chapter), and the ends of wars.

In 1667, Louis XIV opened the first section of the street as a short extension of the Tuileries Garden. This year is considered the birth of Paris as a grand city. The Champs-Elysées soon became the place to cruise in your carriage. (It still is today; traffic can be gridlocked even at midnight.) One hundred years later, the café scene arrived. From the 1920s until the 1960s, this boulevard was pure elegance; Parisians actually dressed up to come here. It was mainly residences, rich hotels, and cafés. Then, in 1963, the government pumped up the neighborhood’s commercial metabolism by bringing in the RER (commuter train). Suburbanites had easy access, and pfft—there went the neighborhood.

• Start your descent, pausing at the first tiny street you cross, Rue de Tilsitt. This street is part of a shadow ring road—an option for drivers who’d like to avoid the chaos of the Arc—complete with stoplights.

Rue de Tilsitt and Qatar Embassy

Rue de Tilsitt and Qatar EmbassyA few steps down Rue de Tilsitt is a building housing the Qatar Embassy. It’s one of the few survivors of a dozen uniformly U-shaped buildings from Haussmann’s original 1853 grand design.

Back on the main drag, look across to the other side of the Champs-Elysées at the big, gray, concrete-and-glass “Publicis” building. Ugh. In the 1960s, venerable old buildings (similar to the Qatar Embassy building) were leveled to make way for new commercial operations like Publicis. Then, in 1985, a law prohibited the demolition of the old building fronts that gave the boulevard a uniform grace. Today, many modern businesses hide behind preserved facades.

The nouveau Champs-Elysées, revitalized in 1994, has newer benches and lamps, broader sidewalks, all-underground parking, and a fleet of green-suited workers who drive motorized street cleaners. Blink away the modern elements, and it’s not hard to imagine the boulevard pre-1963, with only the finest structures lining both sides all the way to the palace gardens.

McDonald’s

McDonald’sThe arrival of McDonald’s—a hundred yards farther down on the left at #140—was a shock to the boulevard...and to the country. At first it was allowed to have only white arches painted on the window. Today, dining chez MacDo has become typically Parisian. France has a thousand McDonald’s, and the Champs-Elysées branch is considered the most profitable one in the world.

A Big Mac here buys an hour of people-watching. Notice how many of the happy clients are French. The popularity of le fast-food in Paris is a sign that life is changing, and that the era of two-hour lunches is over. The most commonly ordered dish in French restaurants is now—by far and away—the hamburger (both as fast food and as a trendy gourmet dish). The French must now compete in a global world, and if that means adopting a more American lifestyle, c’est la vie.

Glitz: Peugeot, Mercedes-Benz, Lido

Glitz: Peugeot, Mercedes-Benz, LidoFancy car dealerships include Peugeot, at #136 (showing off its futuristic concept cars, often alongside the classic models), and Mercedes-Benz, a block down at #118, where you can pick up a Mercedes bag and perfume to go with your new car. In the 19th century this was an area for horse stables; today, it’s the district of garages, limo companies, and car dealerships. If you’re serious about selling cars in France, you must have a showroom on the Champs-Elysées.

Next to Mercedes is the famous Lido, Paris’ largest cabaret (and a multiplex cinema). You can walk all the way into the lobby, passing a video advertising the show. Paris still offers the kind of burlesque-type spectacles that have been performed here since the 19th century, combining music, comedy, and scantily clad women. Moviegoing on the Champs-Elysées provides another kind of fun, with theaters showing the very latest releases. Check to see if there are films you recognize, then look for the showings (séances). A “v.o.” (version originale) next to the time indicates the film will be shown in its original language; a “v.f.” stands for version française.

Two doors farther down is Petit Bateau. The store’s presence on the Champs-Elysées is proof of the success of the government’s efforts to encourage couples to have more babies. With generous financial rewards for each child, France’s birthrate is well above the rest of Europe’s.

• Next, cross the boulevard from in front of the Mercedes showroom—but pause at the center on your way across for the next green light so you’ll have time to enjoy the view and energy. Look up at the Arc de Triomphe, its rooftop bristling with tourists. Notice the variety of architecture along this street—old and elegant, new, and new-behind-old-facades. Continue to #101.

Louis Vuitton

Louis VuittonThe flagship store of this famous producer of leather bags may be the largest single-brand luxury store in the world. Step inside. The store insists on providing enough salespeople to treat each customer royally—if there’s a line, it means shoppers have overwhelmed the place. If you need clothing and shoes to put in your fancy new bag, head upstairs.

• Continue downhill. Cross Avenue Georges V and find Fouquet’s, a Paris institution. The white spire you see down Avenue Georges V is the American Cathedral.

Café Culture: Fouquet’s and Ladurée

Café Culture: Fouquet’s and LaduréeFouquet’s café-restaurant (#99), under the red awning, is a popular spot among French celebrities, serving the most expensive shot of espresso I’ve found in downtown Paris (€10). Opened in 1899 as a coachman’s bistro, Fouquet’s gained fame as the hangout of France’s WWI biplane fighter pilots—those who weren’t shot down by Germany’s infamous “Red Baron.” It also served as James Joyce’s dining room.

Since the early 1900s, Fouquet’s has been a favorite of French celebrities. The golden plaques at the entrance honor winners of France’s Oscar-like film awards, the Césars (one is cut into the ground at the end of the carpet). There are plaques for Gérard Depardieu, Catherine Deneuve, Yves Montand, Roman Polanski, Juliette Binoche, and several famous Americans (but not Jerry Lewis). More recent winners are shown on the floor just inside. Every February, after the Césars are handed out at a nearby theater, France’s biggest movie stars descend on Fouquet’s. Here they emerge from their limos for the night’s grandest red-carpet event as they make their way inside for the official gala dinner.

The hushed interior is at once classy and intimidating—and also a grand experience...if you dare (to say “I’m just looking” in French, say “Je regarde”—zhuh ruh-gard—though fluent English is spoken). The outdoor setting is more relaxed, but everyone still looks rich and famous to me.

Once threatened with foreign purchase and eventual destruction, Fouquet’s was spared that fate when the government declared it a historic monument. The café has now become something of a symbol of excess in a country polarized by a rich-poor gap. Case in point: Flamboyant ex-President Nicolas Sarkozy celebrated his election-night victory with a huge party at Fouquet’s, attended by France’s glitterati—including the “French Elvis,” Johnny Hallyday. By contrast, current President François Hollande, a Socialist, spent his election night in his humble hometown and does not frequent Fouquet’s.

Ladurée (two blocks downhill at #75) is a classic 19th-century tea salon/restaurant/pâtisserie. Nonpatrons can discreetly wander around the place, though photos are not allowed. A coffee here is très élégant (only €4; I prefer the tables upstairs). The bakery sells traditional macarons, cute little cakes, and gift-wrapped finger sandwiches to go (your choice of four mini-macarons for €10). The rear café-bar feels otherworldly bizarre.

• Cross back to the lively (north) side of the street and find two good-value lunch options, Boulangerie Paul and La Brioche Dorée (described in the sidebar on here). At #92 (50 yards uphill), a wall plaque marks the  place Thomas Jefferson lived while serving as minister to France (1785-1789). He replaced the popular Benjamin Franklin but quickly made his own mark, extolling the virtues of America’s Revolution to a country approaching its own.

place Thomas Jefferson lived while serving as minister to France (1785-1789). He replaced the popular Benjamin Franklin but quickly made his own mark, extolling the virtues of America’s Revolution to a country approaching its own.

French Shopping: Arcades Mall, Sephora, Guerlain

French Shopping: Arcades Mall, Sephora, GuerlainStroll into the Arcades des Champs-Elysées mall at #76. With its fancy lamps, mosaic floors, glass skylight, and classical columns (try to ignore the Starbucks), it captures faint echoes of the années folles—the “crazy years,” as the Roaring ’20s were called in France. Architecture buffs can observe how the flowery Art Nouveau of the 1910s became the simpler, more geometric Art Deco of the 1920s.

Down the street at #74, the Galerie du Claridge building sports an old facade. You’d never guess that its ironwork awning, balconies, putti, and sculpted fantasy faces disguise an otherwise new building. One of the current tenants is FNAC, a large French chain that sells electronics, CDs, rare vinyl, concert tickets, and skip-the-queue tickets for many Paris sights (see here).

For a noisy and fragrant commercial carnival of perfumes, and a chance to sense the French passion for cosmetics, take your nose sightseeing at #72 and glide down the ramp of the largest Sephora in France. Grab a disposable white strip from a lovely clerk, spritz it with a sample, and sniff. The entry hall is lined with new products. In the main showroom, women’s perfumes line the right wall and men’s line the left—organized alphabetically by company, from Armani to Versace.

While Sephora seems to be going all out to attract the general public, the venerable Guerlain perfume shop sits next door and shows off a dash of the Champs-Elysées’ old gold-leaf elegance. Notice the 1914 details. Climb upstairs. It’s très French. If Sephora is a mosh-pit for your nose, Guerlain is a harem.

At the intersection with Rue la Boëtie, the English-speaking pharmacy is open until midnight (entrance around the corner).

Car buffs should detour across the Champs and park themselves at the sleek café in the  Renault store (open until midnight). The car exhibits change regularly, but the great tables looking down onto the Champs-Elysées are permanent.

Renault store (open until midnight). The car exhibits change regularly, but the great tables looking down onto the Champs-Elysées are permanent.

International Shopping and Citroën

International Shopping and CitroënBack on earth, a half-block farther down on the north side, the Disney, Gap, Zara, Nike, and Banana Republic stores are reminders of global economics: The French may live in a world of their own, but they love these places as much as Americans do. For a classic French brand, check out the five floors of glassy glitz at the Citroën auto showroom at #42. This isn’t your father’s deux chevaux, though you’ll see echoes of that simple-but-dependable “two-horsepower” car from the ’50s and ’60s. Across the street at #23, that massive gilded gate and green alley no longer lead to a private mansion, but to Abercrombie & Fitch.

Rond-Point

Rond-PointAt the Rond-Point des Champs-Elysées, the shopping ends and the park begins. This round, leafy traffic circle is always colorful, lined with flowers or seasonal decorations (thousands of pumpkins at Halloween, hundreds of decorated trees at Christmas). Avenue Montaigne, jutting off to the right, is lined by the most exclusive shops in town—the kinds of places where you need to make an appointment to buy a dress.

• If you’re pooped, Rond-Point’s Métro stop is a good place to cut this walk short. Otherwise, continue downhill on the left side. Arc around Rond-Point and stroll for about 200 yards farther downhill. At Avenue de Marigny, look to the other side of the Champs-Elysées to find a  statue of Charles de Gaulle—ramrod-straight and striding purposefully, as he did the day Paris was liberated in 1944.

statue of Charles de Gaulle—ramrod-straight and striding purposefully, as he did the day Paris was liberated in 1944.

Grand and Petit Palais

Grand and Petit PalaisFrom the statue of de Gaulle, a grand boulevard (Avenue Winston Churchill) passes through the site of the 1900 World’s Fair, leading between the glass-and-steel-domed Grand and Petit Palais exhibition halls, and across the river over the ornate bridge called Pont Alexandre III. (You can view these sights from the statue, if you don’t feel like walking down to the bridge.) Imagine pavilions like the two you see today lining this street all the way to the golden dome of Les Invalides—examples of the “can-do” spirit that ran rampant in Europe at the dawn of the 20th century.

Today, the huge Grand Palais (on the right side) houses impressive temporary exhibits. Classical columns and giant, colorful mosaics running the length of the Palais’ facade wowed fairgoers. The Petit Palais (left side) has a pleasing permanent collection of lesser paintings by Courbet, Monet, Pissarro, and other 19th-century masters. It’s a breathtaking building with a peaceful café (worth a quick detour), and just as important, the Petit Palais is free to enter and has fine WCs with no lines. For more on both museums, see here.

The exquisite Pont Alexandre III, spiked with golden statues and ironwork lamps, was built to celebrate a turn-of-the-20th-century treaty between France and Russia. The grand and gilded dome in the distance marks Les Invalides, built by Louis XIV as a veterans’ hospital for his battle-weary troops (covered in the Army Museum and Napoleon’s Tomb Tour). The esplanade leading up to Les Invalides—possibly the largest patch of accessible grass in the city—gives soccer balls and Frisbees a warm Paris welcome.

• From the de Gaulle statue it’s a straight shot down the rest of the Champs-Elysées to the finish line. (Speaking of finish lines, this stretch is where the Tour de France reaches its annual climax—see sidebar.) The plane trees that you’ll see—a kind of sycamore with peeling bark—do well in big-city pollution. They’re a legacy of Napoleon III—president/emperor from 1849 to 1870—who had 600,000 trees planted to green up the city.

Since there’s little to see on this final stretch of the Champs-Elysées, consider the following alternate route to Place de la Concorde. From the statue, circle clockwise to the left up Avenue de Marigny to the well-secured Elysée Palace, France’s version of the White House. It feels like London’s #10 Downing Street but with French style. From there you’ll walk five blocks along Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré—past the fortified backsides of the US and British embassies and glittering high-end shops—and then cut back down to Place de la Concorde.

Either way, your final destination is the 21-acre Place de la Concorde. View it from the obelisk in the center.

Place de la Concorde

Place de la ConcordeDuring the Revolution, this was the Place de la Révolution. The guillotine sat on this square, and many of the 2,780 people who were beheaded during the Revolution lost their bodies here during the Reign of Terror. A bronze plaque in the ground in front of the obelisk memorializes the place where Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette, Georges Danton, Charlotte Corday, and Maximilien de Robespierre, among about 1,200 others, were made “a foot shorter on top.” Three people worked the guillotine: One managed the blade, one held the blood bucket, and one caught the head, raising it high to the roaring crowd. (In 1981, France abolished the death penalty—one of many preconditions for membership in today’s European Union.)

The 3,300-year-old, 72-foot, 220-ton, red granite, hieroglyph-inscribed obelisk of Luxor now forms the centerpiece of Place de la Concorde. Here—on the spot where Louis XVI was beheaded—his brother (Charles X) erected this obelisk to honor those who’d been executed. (Charles became king when the monarchy was restored after Napoleon.) The obelisk was carted here from Egypt in the 1830s. The gold pictures on the pedestal tell the story of the obelisk’s incredible two-year journey: pulled down from the entrance to Ramses II’s Temple of Amon in Luxor; encased in wood; loaded onto a boat built to navigate both shallow rivers and open seas; floated down the Nile, across the Mediterranean, along the Atlantic coast, and up the Seine; and unloaded here, where it was reerected in 1836. Its glittering gold-leaf cap is a recent addition (1998), replacing the original, which was stolen 2,500 years ago.

The obelisk also forms a center point along a line that locals call the “royal perspective.” You can hang a lot of history along this straight line (Louvre-obelisk-Arc de Triomphe-Grande Arche de la Défense). The Louvre symbolizes the old regime (divine-right rule by kings and queens). The obelisk and Place de la Concorde symbolize the people’s Revolution (cutting off the king’s head). The Arc de Triomphe calls to mind the triumph of nationalism (victorious armies carrying national flags under the arch). And the huge modern arch in the distance, surrounded by the headquarters of multinational corporations, heralds a future in which business entities are more powerful than nations.

• Our walk is over. From here the closest Métro stop is Concorde (entrance on the Tuileries Garden side of the square, away from the river); handy buses #24 and #73 (see page 32) stop in the square; and taxis congregate outside Hôtel Crillon. But if you’re not quite ready to go, Paris has more to offer...

The beautiful Tuileries Garden (with a public WC just inside on the right) is just through the iron gates. Pull up a chair next to a pond or at one of the cafés in the garden. From the garden you can access the Orangerie Museum and, at the other end, the Louvre (this book includes tours of both museums).

On the north side of Place de la Concorde is  Hôtel Crillon, one of Paris’ most exclusive hotels (likely closed for renovation for at least part of 2017). Of the twin buildings that guard the entrance to Rue Royale (which leads to the Greek-style Church of the Madeleine), it’s the one on the left. This hotel is so fancy that one of its belle époque rooms is displayed in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Eleven years before Louis XVI lost his head on Place de la Concorde, he met with Benjamin Franklin in this hotel to sign a treaty recognizing the US as an independent country. (Today’s low-profile, heavily fortified US Embassy and Consulate are located next door.)

Hôtel Crillon, one of Paris’ most exclusive hotels (likely closed for renovation for at least part of 2017). Of the twin buildings that guard the entrance to Rue Royale (which leads to the Greek-style Church of the Madeleine), it’s the one on the left. This hotel is so fancy that one of its belle époque rooms is displayed in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Eleven years before Louis XVI lost his head on Place de la Concorde, he met with Benjamin Franklin in this hotel to sign a treaty recognizing the US as an independent country. (Today’s low-profile, heavily fortified US Embassy and Consulate are located next door.)

Nearby, those of a certain generation may want to seek out Maxim’s restaurant (3 Rue Royale), once the world’s most glamorous bistro (c. 1900-1970) and a nightspot frequented by everyone from British royalty to Jackie O. Today, its famed carved-wood, Art Nouveau exterior and high prices remain intact, but it’s become a generic link in a chain franchise. Farther north up Rue Royale is a fancy shopping area near Place de la Madeleine (see the Shopping in Paris chapter).

South of Place de la Concorde is the  Pont de la Concorde, the bridge that leads to the many-columned building where the French National Assembly (similar to the US Congress) meets. The Pont de la Concorde, built of stones from the Bastille prison (which was demolished by the Revolution in 1789), symbolizes the concorde (harmony) that can come from chaos—through good government. The bridge arcs over a freeway underpass that was converted to a pedestrian-only promenade in 2014 and is well worth a stroll.

Pont de la Concorde, the bridge that leads to the many-columned building where the French National Assembly (similar to the US Congress) meets. The Pont de la Concorde, built of stones from the Bastille prison (which was demolished by the Revolution in 1789), symbolizes the concorde (harmony) that can come from chaos—through good government. The bridge arcs over a freeway underpass that was converted to a pedestrian-only promenade in 2014 and is well worth a stroll.

Stand midbridge and gaze upriver (east). The Orangerie hides behind the trees at 10 o’clock, and the tall building with the skinny chimneys at 11 o’clock is the architectural caboose of the sprawling Louvre palace. The thin spire of Sainte-Chapelle is dead center at 12 o’clock, with the twin towers of Notre-Dame to its right. The Orsay Museum is closer on the right, connected with the Tuileries Garden by a sleek pedestrian bridge (the next bridge upriver) or by the riverside promenade on the Left Bank. Paris awaits.