Centre Pompidiou

FIFTH FLOOR: MODERN ART (1905-1980)

FOURTH FLOOR: CONTEMPORARY ART FROM 1980 TO THE PRESENT

Some people hate modern art. But the Pompidou Center contains what is possibly Europe’s best collection of 20th-century art. After the super-serious Louvre and Orsay museums, finish things off with this artistic kick in the pants. You won’t find classical beauty here—no dreamy Madonnas-and-children—just a stimulating, offbeat, and, if you like, instructive walk through nearly every art style of the wild-and-crazy last century.

The Pompidou’s “permanent” collection...isn’t. It changes so often that a painting-by-painting tour is impossible. So this chapter is more a general overview of the major trends of 20th-century art, with emphasis on artists you’re likely to find in the Pompidou. Read this chapter ahead of time for background, or take it with you to the museum to look up specific painters as you stumble across their work. See the classics—Picasso, Matisse, etc.—but be sure to leave time to browse the thought-provoking and fun art of more recent artists.

Cost: The €14 ticket gets you into all of the building’s various exhibits—both the permanent collection (the Musée National d’Art Moderne) and the special exhibits that make this place so edgy. The €3 View of Paris ticket lets you ride to the sixth floor for the view but doesn’t cover museum entry. The Museum Pass includes access to the permanent collection, the sixth floor view, and occasional special exhibits (but for special exhibits that are not covered, passholders can’t buy a simple supplement to make up the difference).

Buy tickets on the ground floor. If lines are long, use the red ticket machines (credit cards only). The museum is free on the first Sunday of the month.

Hours: Permanent collection open Wed-Mon 11:00-21:00, closed Tue, ticket counters close at 20:00; rest of the building open later—until 22:00 (Thu until 23:00). To avoid crowds (mainly for the special exhibits), arrive after 17:00.

Getting There: Take the Métro to Rambuteau or Hôtel de Ville. Bus #69 from the Marais and Rue Cler also stops a few blocks away at Hôtel de Ville. The wild, color-coded exterior of the museum makes it about as hard to locate as the Eiffel Tower.

Information: There’s a helpful info desk in the lobby. The Espace de Médiation on the fifth floor is the museum’s main information office. Note that Parisians call the complex the “Centre Beaubourg” (sahn-truh boh-boor), but official publications call it the “Centre Pompidou.” The free “Centre Pompidou” app covers both the permanent collection and special exhibits. Tel. 01 44 78 12 33, www.centrepompidou.fr.

Length of This Tour: Allow one hour.

Services: Baggage check is free and required for bags bigger than a large purse. The terrific museum store on the main floor has zany gift ideas. There’s also free Wi-Fi.

Photography: Allowed in the permanent collection, but no flash.

Cuisine Art: You’ll find a sandwich-and-coffee café on the mezzanine (nice interior views, a bit pricey for its simple fare) and a gourmet view restaurant on the sixth floor (worth the splurge for a coffee-with-view, though I would not eat here). Outside the museum, the neighborhood abounds with cheap bistros and crêpe stands. My favorite places line the little square south of the museum (look for the playful fountain, an homage to composer Igor Stravinsky). Dame Tartine and Crêperie Beaubourg both have reasonable prices. The Monop’ grocery store on the square across from the museum (#135) has all you need for a picnic.

View Art: The sixth floor has stunning views of the Paris cityscape. Your Pompidou ticket or Museum Pass gets you there, or you can buy the €3 View of Paris ticket (good for the sixth floor only; doesn’t include museum entry).

Nearby: The studio of sculptor Constantin Brancusi (see here) is housed in the gray concrete bunker in front of the Pompidou and is free to visit. Brancusi (1876-1957) often hosted Paris’ artistic glitterati in his humble studio, where he served home-cooked dishes of his native Romania. After Brancusi’s death, the Pompidou Center had the studio reconstructed here. See the unique space and some of his revolutionary work (Wed-Mon 14:00-18:00, closed Tue, same contact info as Pompidou).

Just a few blocks west, the new glass-and-steel canopy covering part of the Forum des Halles shopping mall is the centerpiece of a €1 billion facelift that many locals view as a colossal waste of money (see here).

Starring: Matisse, Picasso, Chagall, Dalí, Warhol, and contemporary art.

That slight tremor you may feel comes from Italy, where Michelangelo has been spinning in his grave ever since 1977, when the Pompidou Center first disgusted Paris. Still, it’s an appropriate modern temple for the controversial art it houses.

The building itself is “exoskeletal” (like Notre-Dame, or a crab), with its functional parts—the pipes, heating ducts, and escalator—on the outside and the meaty art inside. It’s the epitome of modern architecture, where “form follows function.”

This chapter covers the Musée National d’Art Moderne: Collection Permanente (labeled simply Musée on signs), which is on the fourth and fifth floors. But there’s plenty more art scattered all over the building. Ask at the ground-floor information booth, or just wander. Generally, art from 1905 to 1980 is on the fifth floor (the core of this chapter), while the fourth floor contains more recent art. But 20th-century art resents being put in chronological order, and the Pompidou’s collection is rarely in any neat-and-tidy arrangement. Use the museum’s floor plans (posted on the wall) to find select artists. The museum is bigger than you think—and you’re smart to focus on a limited number of artists. Don’t hesitate to ask, “Où est Kandinsky?”

Remember, the following text is not a “tour” of the museum—it’s a chronological overview of modern art.

• Buy your ticket on the ground floor, then ride up the escalator (or run up the down escalator to get in the proper mood). When you see the view, your opinion of the Pompidou’s exterior should improve a good 15 percent. Find the permanent collection—the entrance is either on the fourth or fifth floor (it varies). Enter and show your ticket.

Start your tour on the fifth floor, make several spins, and click your heels. Toto, we’re not in Kansas anymore.

A.D. 1900: A new century dawns. War is a thing of the past. Science will wipe out poverty and disease. Rational Man is poised for a new era of peace and prosperity...

Right. This cozy Victorian dream was soon shattered by two world wars and rapid technological change. Nietzsche murdered God. Freud washed ashore on the beach of a vast new continent inside each of us. Einstein made everything merely “relative.” Even the fundamental building blocks of the universe, atoms, were behaving erratically.

The 20th century—accelerated by technology and fragmented by war—was exciting and chaotic, and the art reflects the turbulence of that century of change.

Paris in the early 1900s was the cradle of modern art. For the previous 300 years (1600-1900), Paris had been the capital of the wealthiest, most civilized nation on earth. Europe’s major artists—most of whom spoke French—flocked to Paris, knowing that if you could make it there, you’d make it anywhere.

The groundwork of modern art was first laid by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists in the late 1800s. They pioneered the notion that the painted surface—of thick, colorful brushstrokes—was as inherently interesting as the subject itself. You can almost see the evolution: Monet’s blurry Water Lilies canvases are patterns of color similar to a purely abstract canvas. Van Gogh would build a figure out of brushstrokes of different colors, Cezanne would turn those brushstrokes into patches of paint, then Picasso sharpened those patches into “cubes,” which he would later shatter beyond recognition.

As you tour the Pompidou, remember that most of the artists, including foreigners, spent their formative years in Paris. In the 1910s, funky Montmartre was the mecca of Modernism—the era of Picasso, Braque, and Matisse. In the 1920s the center shifted to the grand cafés of Montparnasse, where painters mingled with American expats such as Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein. During World War II, it was Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialist scene around St. Germain-des-Prés. After World War II, the global art focus moved to New York, but by the late 20th century, Paris had reemerged as a cultural touchstone for the world of modern art.

The Fauves (“wild beasts”) were artists inspired by African and Oceanic masks and voodoo dolls; they tried to inject a bit of the jungle into bored French society. The result? Modern art that looked primitive: long, masklike faces with almond eyes; bright, clashing colors; simple figures; and “flat,” two-dimensional scenes.

Matisse’s colorful “wallpaper” works are not realistic. A man is a few black lines and blocks of paint. The colors are unnaturally bright. There’s no illusion of the distance and 3-D that were so important to Renaissance Italians. The “distant” landscape is as bright as any close-up, and the slanted lines meant to suggest depth are crudely done.

Traditionally, the canvas was like a window you looked “through” to see a slice of the real world stretching off into the distance. Now, a camera could do that better. With Matisse, you look “at” the canvas, like wallpaper. Voilà! What was a crudely drawn scene now becomes a sophisticated and decorative pattern of colors and shapes.

Though fully “modern,” Matisse built on 19th-century art—the bright colors of Vincent van Gogh, the primitive figures of Paul Gauguin, the colorful designs of Japanese prints, and the Impressionist patches of paint that blend together only at a distance.

I throw a rock at a glass statue, shatter it, pick up the pieces, and glue them onto a canvas. I’m a Cubist.

Born in Spain, Picasso moved to Paris as a young man, settling into a studio (Le Bateau-Lavoir) in Montmartre (see here). He worked with next-door neighbor Georges Braque in poverty so dire they often didn’t know where their next bottle of wine was coming from. They corrected each other’s paintings (it’s hard to tell whose is whose without the titles), and they shared ideas, meals, and girlfriends while inventing a whole new way to look at the world.

They show the world through a kaleidoscope of brown and gray. The subjects are somewhat recognizable (with the help of the titles), but they are broken into geometric shards (let’s call them “cubes,” though there are many different shapes), then pieced back together.

Cubism gives us several different angles of the subject at once—say, a woman seen from the front and side angles simultaneously, resulting in two eyes on the same side of the nose. This involves showing three dimensions, plus Einstein’s new fourth dimension, the time it takes to walk around the subject to see other angles. Newfangled motion pictures could capture this moving 4-D world, but how to do it on a 2-D canvas? The Cubist “solution” is a kind of Mercator projection, where the round world is sliced up like an orange peel and then laid as flat as possible.

Notice how the “cubes” often overlap. A single cube might contain both an arm (in the foreground) and the window behind (in the background), both painted the same color. The foreground and the background are woven together, so that the subject dissolves into a pattern.

If the Cubists were as smart as Einstein, why couldn’t they draw a picture to save their lives? Picasso was one modern artist who could draw exceptionally well (see his partly finished Harlequin). But he constantly explored and adapted his style to new trends, and so became the most famous painter of the century. Scattered throughout the museum are works from the many periods of Picasso’s life.

Picasso soon began to use more colorful “cubes” (1912-1915). Eventually, he used curved shapes to build the subject, rather than the straight-line shards of early Cubism.

Picasso married and had children. Works from this period (the 1920s) are more realistic, with full-bodied (and big-nosed) women and children. He tries to capture the solidity, serenity, and volume of classical statues.

As his relationships with women deteriorated, he vented his sexual demons by twisting the female body into grotesque balloon-animal shapes (1925-1931).

All through his life, Picasso explored new materials. He made collages, tried his hand at making “statues” out of wood, wire, or whatever, and even made statues out of everyday household objects. These multimedia works, so revolutionary at the time, have become stock-in-trade today.

For more about Picasso, see the Picasso Museum chapter.

For more about Picasso, see the Picasso Museum chapter.

At age 22, Marc Chagall arrived in Paris with the wide-eyed wonder of a country boy. Lovers are weightless with bliss. Animals smile and wink at us. Musicians, poets, peasants, and dreamers ignore gravity, tumbling in slow-motion circles high above the rooftops. The colors are deep, dark, and earthy—a pool of mystery with figures bleeding through below the surface. (Chagall claimed his early poverty forced him to paint over used canvases, inspiring the overlapping images.)

Chagall’s very personal style fuses many influences. He was raised in a small Belarus village, which explains his “naive” outlook and fiddler-on-the-roof motifs. His simple figures are like Russian Orthodox icons, and his Jewish roots produced Old Testament themes. Stylistically, he’s thoroughly modern—Cubist shards, bright Fauve colors, and Primitive simplification. This otherworldly style was a natural for religious works, and so his murals and stained glass, which feature both Jewish and Christian motifs, decorate buildings around the world—including the ceiling of Paris’ Opéra Garnier (see here).

Fernand Léger’s style has been called “Tubism”—breaking the world down into cylinders, rather than cubes. (He supposedly got his inspiration during World War I from the gleaming barrel of a cannon.) Léger captures the feel of the encroaching Age of Machines, with all the world looking like an internal-combustion engine.

Abstract art simplifies. A man becomes a stick figure. A squiggle is a wave. A streak of red expresses anger. Arches make you want a cheeseburger. These are universal symbols that everyone from a caveman to a banker understands. Abstract artists capture the essence of reality in a few lines and colors, and they capture things even a camera can’t—emotions, abstract concepts, musical rhythms, and spiritual states of mind. Again, with abstract art, you don’t look through the canvas to see the visual world, but at it to read the symbolism of lines, shapes, and colors.

The bright colors, bent lines, and lack of symmetry tell us that Kandinsky’s world was passionate and intense.

Notice titles like Improvisation and Composition. Kandinsky was inspired by music, an art form that’s also “abstract,” though it still packs a punch. Like a jazz musician improvising a new pattern of notes from a set scale, Kandinsky plays with new patterns of related colors as he looks for just the right combination. Using lines and color, Kandinsky translates the unseen reality into a new medium...like lightning crackling over the radio. Go, man, go.

Like a blueprint for Modernism, Mondrian’s T-square style boils painting down to its basic building blocks (black lines, white canvas) and the three primary colors (red, yellow, and blue), all arranged in orderly patterns.

(When you come right down to it, that’s all painting ever has been. A schematic drawing of, say, the Mona Lisa shows that it’s less about a woman than about the triangles and rectangles of which she’s composed.)

Mondrian started out painting realistic landscapes of the orderly fields in his native Netherlands. Increasingly, he simplified them into horizontal and vertical patterns. For Mondrian, who was heavy into Eastern mysticism, “up vs. down” and “left vs. right” were the perfect metaphors for life’s dualities: “good vs. evil,” “body vs. spirit,” “man vs. woman.” The canvas is a bird’s-eye view of Mondrian’s personal landscape.

Brancusi’s curved, shiny statues reduce objects to their essence. A bird is a single stylized wing, the one feature that sets it apart from other animals. He rounds off to the closest geometrical form, so a woman’s head becomes a perfect oval on a cubic pedestal.

Humans love symmetry (maybe because our own bodies are roughly symmetrical) and find geometric shapes restful, even worthy of meditation. Brancusi follows the instinct for order that has driven art from earliest times, from circular Stonehenge and Egyptian pyramids, to Greek columns and Roman arches, to Renaissance symmetry and the Native American “medicine wheel.”

Paul Klee’s small and playful canvases are deceptively simple, containing shapes so basic they can be read as universal symbols. Klee thought a wavy line, for example, would always suggest motion, whereas a stick figure would always mean a human—like the psychiatrist Carl Jung’s universal dreams and symbols manifesting the “collective unconscious.”

Klee saw these universals in the art of children, who express themselves without censoring or cluttering things up with learning. His art has a childlike playfulness and features simple figures painted in an uninhibited frame of mind.

Klee also turned to nature. The same forces that cause the wave to draw a line of foam on the beach can cause a meditative artist to draw a squiggly line of paint on a canvas. The result is a universal shape. True artists don’t just paint nature, they become Nature.

This married couple both painted colorful, fragmented canvases (including a psychedelic Eiffel Tower) that prove the modern style doesn’t have to be ugly or enigmatic.

If you can’t handle modern art, sit on it! (Actually, please don’t.) The applied arts—chairs, tables, lamps, and vases—are as much a part of the art world as the fine arts. (Some say the first art object was the pot.) As machines became as talented as humans, artists embraced new technology and mass production to bring beauty to the masses.

Ankle-deep in mud, a soldier shivers in a trench, waiting to be ordered “over the top.” He’ll have to run through barbed wire, over fallen comrades, and into a hail of machine-gun fire, only to capture a few hundred yards of meaningless territory that will be lost the next day. This soldier was not thinking about art.

World War I left nine million dead. (During the war, France lost more men in the Battle of Verdun than America lost in the entire Vietnam War.) The war also killed the optimism and faith in mankind that had guided Europe since the Renaissance. Now, rationality just meant schemes, technology meant machines of death, and morality meant giving your life for an empty cause.

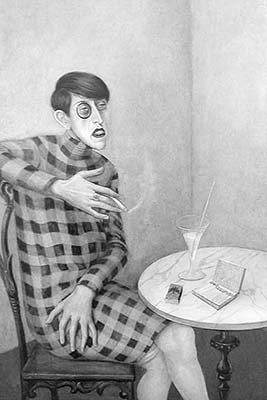

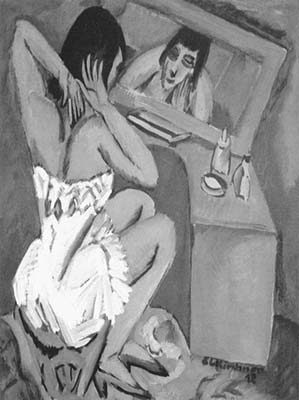

Cynicism and decadence settled over postwar Europe, and artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Chaïm Soutine, Otto Dix, and Oskar Kokoschka recorded it. They “expressed” their disgust by showing a distorted reality that emphasized the ugly. Using the lurid colors and simplified figures of the Fauves, they slapped paint on in thick brushstrokes and depicted a hypocritical, hard-edged, dog-eat-dog world that had lost its bearings. The people have a haunted look in their eyes—the fixed stare of corpses and those who have to bury them.

When people could grieve no longer, they turned to grief’s giddy twin: laughter. The war made all old values, including art, a joke. The Dada movement, choosing a purposely childish name, made art that was intentionally outrageous: a moustache on the Mona Lisa, a shovel hung on a wall, or a modern version of a Renaissance “fountain”—a urinal (by either Marcel Duchamp, or I. P. Freeley, 1917). It was a dig at all the pompous prewar artistic theories based on the noble intellect of Rational Women and Men. While the experts ranted on, Dadaists sat in the back of the class and made cultural fart noises.

Hey, I love this stuff. My mind says it’s sophomoric, but my heart belongs to Dada.

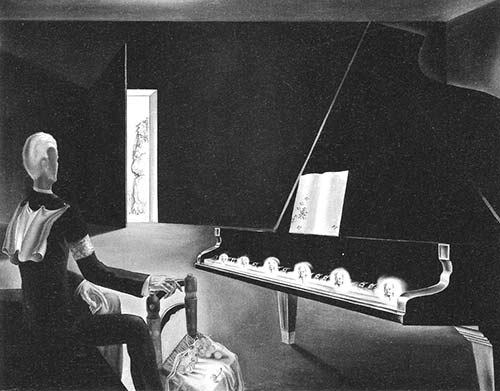

Greek statues with sunglasses, a man as a spinning top, shoes becoming feet, and black ants as musical notes...Surrealism. The world was moving fast, and Surrealist artists such as Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and René Magritte caught the jumble of images. The artist scatters seemingly unrelated items on the canvas, which leaves us to trace the links in a kind of connect-the-dots without numbers. If it comes together, the synergy of unrelated things can be pretty startling. But even if the juxtaposed images don’t ultimately connect, the artist has made you think, rerouting your thoughts through new neural paths. If you don’t “get” it...you got it.

Complicating the modern world was Freud’s discovery of the “unconscious” mind that thinks dirty thoughts while we sleep. Many a Surrealist canvas is an uncensored, stream-of-consciousness “landscape” of these deep urges, revealed in the bizarre images of dreams.

In dreams, sometimes one object can be two things at once: “I dreamt that you walked in with a cat...no, wait, maybe you were the cat...no....” Surrealists paint opposites like these and let them speak for themselves.

Salvador Dalí could draw exceptionally well. He painted “unreal” scenes with photographic realism, thus making us believe they could really happen. Seeing familiar objects in an unfamiliar setting—like a grand piano adorned with disembodied heads of Lenin—creates an air of mystery, the feeling that anything can happen. That’s both exciting and unsettling. Dalí’s images—crucifixes, political and religious figures, naked bodies—pack an emotional punch. Take one mixed bag of reality, jumble in a blender, and serve on a canvas...Surrealism.

Abstract artists such as Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, and Jean Arp described their subconscious urges using color and shapes alone, like Rorschach inkblots in reverse.

The thin-line scrawl of Joan Miró’s work is like the doodling of a three-year-old. You’ll recognize crudely drawn birds, stars, animals, and strange cell-like creatures with whiskers (“Biological Cubism”). Miró was trying to express the most basic of human emotions using the most basic of techniques.

Alexander Calder’s mobiles hang like Mirós in the sky, waiting for a gust of wind to bring them to life.

And talk about a primal image! Jean Arp builds human beings out of amoeba-like shapes.

Young Georges Rouault was apprenticed to a maker of stained-glass windows. Enough said?

His paintings have the same thick, glowing colors, heavy black outlines, simple subjects, and (mostly) religious themes. The style is modern, but the mood is medieval, solemn, and melancholy. Rouault captures the tragic spirit of those people—clowns, prostitutes, and sons of God—who have been made outcasts by society.

Most 20th-century paintings are a mix of the real world (“representation”) and the colorful patterns of “abstract” art. Artists purposely distort camera-eye reality to make the resulting canvas more decorative. So, Picasso flattens a woman into a pattern of colored shapes, Pierre Bonnard makes a man from a shimmer of golden paint, and Balthus turns a boudoir scene into colorful wallpaper.

Increasingly, you’ll have to focus your eyes to look at the canvases, not through them, especially in art by Jean Dubuffet, Lucio Fontana, and Karel Appel.

Enjoy the lines and colors, but also a new element: texture. Some works have very thick paint piled on—you can see the brushstroke clearly. Some have substances besides paint applied to the canvas, such as Dubuffet’s brown, earthy rectangles of real dirt and organic waste. Fontana punctures the canvas so that the fabric itself (and the hole) becomes the subject. Artists show their skill by mastering new materials. The canvas is a tray, serving up a delightful array of different substances with interesting colors, patterns, shapes, and textures.

Giacometti’s skinny statues have the emaciated, haunted, and faceless look of concentration camp survivors. The simplicity of the figures may be “primitive,” but these aren’t stately, sturdy, Easter Island heads. Here, man is weak in the face of technology and the winds of history.

America emerged from World War II as the globe’s superpower. With Europe in ruins, New York replaced Paris as the art capital of the world. The trend was toward bigger canvases, abstract designs, and experimentation with new materials and techniques. It was called “Abstract Expressionism”—expressing emotions and ideas using color and form alone.

“Jack the Dripper” attacks convention with a can of paint, dripping and splashing a dense web onto the canvas. Picture Pollock in his studio, as he jives to the hi-fi, bounces off the walls, and throws paint in a moment of enlightenment. Of course, the artist loses some control this way—control over the paint flying in midair and over himself, now in an ecstatic trance. Painting becomes a whole-body activity, a “dance” between the artist and his materials.

The act of creating is what’s important, not the final product. The canvas is only a record of that moment of ecstasy.

All those huge, sparse canvases with just a few lines or colors—what reality are they trying to show?

In the modern world, we find ourselves insignificant specks in a vast and indifferent universe. Every morning each of us must confront that big, blank, existentialist canvas and decide how we’re going to make our mark on it. Like, wow.

Another influence was the simplicity of Japanese landscape painting. A Zen master studies and meditates for years to achieve the state of mind in which he can draw one pure line. These canvases, again, are only a record of that state of enlightenment. (What is the sound of one brush painting?)

On more familiar ground, postwar painters were following in the footsteps of artists such as Mondrian, Klee, and Kandinsky (whose work they must have considered “busy”). The geometrical forms here reflect the same search for order, but these artists painted to the 5/4 asymmetry of Dave Brubeck’s jazz classic, “Take Five.”

America’s postwar wealth made the consumer king. Pop Art is created from the “pop”-ular objects of that throwaway society—a soup can, a car fender, mannequins, tacky plastic statues, movie icons, advertising posters.

Is this art? Are all these mass-produced objects beautiful? Or crap? If they’re not art, why do we work so hard to acquire them? Pop Art, like Dada, questions our society’s values.

Warhol (who coined the idea of everyone having “15 minutes of fame” and became a pop star himself) concentrated on another mass-produced phenomenon: celebrities. He took publicity photos of famous people and repeated them. The repetition—like the constant bombardment we get from repeated images on television—cheapens even the most beautiful things.

Pop Art makes you reassess what “beauty” really is. Take something out of Sears and hang it in a museum and you have to think about it in a wholly different way.

• Head to the fourth floor for more contemporary art.

The “modern” world is history. Picasso and his ilk are now gathering dust and boring art students everywhere. Minimalist painting and abstract sculpture are old-school. Enter the “postmodern” world, as seen through the eyes of current artists.

You’ll see fewer traditional canvases or sculptures. Artists have traded paintbrushes for blowtorches (Miró said he was out to “murder” painting), and blowtorches for computer mice. Mixed-media work is the norm, combining painting, sculpture, photography, video/film, digital graphics and computer programming, new resins, plastics, industrial techniques, and lighting and sound systems.

The Pompidou groups the work of these artists under somewhat arbitrary labels—the artist as documentarian, as an archivist of events, or as a producer of commercial goods. Don’t worry about trying to understand these cryptic conceptual labels. Browse the floor and enjoy some of the following trends:

Installations: An entire room is given to an artist to prepare. Like entering an art funhouse, you walk in without quite knowing what to expect. (I’m always thinking, “Is this safe?”) Using the latest technology, the artist engages all your senses by controlling the lights, sounds, and sometimes even the smells.

Digital Media: Holograms replace material objects, and elaborate computer programming creates a fantastic multimedia display.

Assemblages: Artists raid Dumpsters, recycling junk into the building blocks for larger “assemblages.” Each piece is intended to be interesting and tell its own story, and so is the whole sculpture. Weird, useless Rube Goldberg machines make fun of technology.

Natural Objects: A rock in an urban setting is inherently interesting.

The Occasional Canvas: This comes as a familiar relief. Artists of the New Realism labor over painstaking, hyper-realistic canvases to re-create the glossy look of a photo or video image.

Interaction: Some exhibits require your participation, whether you push a button to get the contraption going, touch something, or just walk around the room. In some cases the viewer “does” art, rather than just staring at it. If art is really meant to change, it has to move you—literally.

Deconstruction: Late-20th-century artists critiqued (or “deconstructed”) society by examining our underlying assumptions. One way to do it is to take a familiar object (say, a crucifix) out of its normal context (a church), and place it in a new setting (a jar of urine). Video and film can deconstruct something by playing it over and over, ad nauseam. Ad copy painted on canvas deconstructs itself.

Conceptual Art: The concept of which object to pair with another to produce maximum effect is the key. (Crucifix + urine = million-dollar masterpiece.)

Postmodernism: Artists shamelessly recycled older styles and motifs to create new combinations: Greek columns paired with Gothic arches, Christmas lights, and a hip-hop soundtrack.

Performance Art: This is a kind of mixed media of live performance. Many artists—who in another day would have painted canvases—have turned to music, dance, theater, and performance art. This art form is often interactive, by dropping the illusion of a performance and encouraging audience participation. When you finish with the Pompidou Center, go outside for some of the street theater.

Playful Art: Children love the art being produced today. If it doesn’t put a smile on your face, well, then you must be a jaded grump like me, who’s seen the same repetitious s#%t passed off as “daring” since Warhol stole it from Duchamp. I mean, it’s so 20th century.